Abstract

The risk of developing a solid cancer is a major issue arising in the disease course of a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN). Although the connection between the two diseases has been widely described, the backstage of this complex scenario has still to be explored. Several cellular and molecular mechanisms have been suggested to link the two tumors. Sometimes the MPN is considered to trigger a second cancer but at other times both diseases seem to depend on the same source. Increasing knowledge in recent years has revealed emerging pathways, supporting older, more consolidated theories, but there are still many unresolved issues. Our work aims to present the biological face of the complex clinical scenario in MPN patients developing a second cancer, focusing on the main cellular and molecular pathways linking the two diseases.

1. Introduction

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) (polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), primary myelofibrosis (PMF), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and unspecified MPNs) are chronic hematological cancers featuring different progression rates [1]. Although considered to be relatively indolent malignancies, patients suffer an increased risk of vascular complications, disease progression, leukemic transformation, and hence a reduced life expectancy [1,2].

In recent years, a wide range of studies has shown an increased risk of developing a second cancer (SC) in the different MPN subtypes as compared to the general population [3,4,5,6,7].

A recent meta-analysis collecting data on more than 65,000 MPNs from 12 large studies summarized the main epidemiologic, prognostic and clinical aspects of this condition, aiming to provide clinicians with an overview supporting the disease management [8]. The biological background underlying this complex scenario has perhaps been less widely studied but is clearly equally important. Some biological aspects connecting the two events are MPNs-dependent, others depend on treatment, and still others are bridge mechanisms between the two; often, several processes overlap [8].

The presented work aims to collect data on the main cellular and molecular pathways linking the two neoplasms occurring in MPN patients who develop an SC (Table 1), focusing on what happens and trying to understand when and why.

Table 1.

Main cellular and molecular pathways linking the two neoplasms in MPN patients who develop an SC.

2. Risk of SC Onset in MPNs: An Overview

The frequency of a second solid or lymphoid cancer is increased in patients with chronic MPNs as compared with age-/sex-matched healthy individuals, with the risk of SC such as lymphomas and tumors of the skin, lung, kidney, and thyroid gland being 1.5–3.0-fold higher in MPN patients, especially in the age group spanning 60–80 years [8]. Conversely, the risk of other solid neoplasms such as colon, breast, and prostate cancer was not different from that in the rest of the population [8]. Several large studies followed patients with varying subtypes of MPN and revealed a cumulative incidence of SC ranging from 5 to 10% after 5 years from diagnosis. The different subtypes of MPNs have similar relative increases in the risk of an SC, but the time of onset is shorter in PMF as compared to PV and ET [4].

Few data are available about the prognosis of cancer patients with previous MPNs. A single work studied this aspect, comparing 1246 MPNs and one SC with 5155 age/sex-matched patients with the same cancers but without preceding MPNs [38]. The study showed that survival was significantly poorer for cancer patients following MPN than other cancers, the hazard ratio for death being increased 1.5-fold for cancer patients with antecedent ET, 1.2-fold with PV, and 1.2-fold with CML [38]. Cardiovascular events, thrombosis and infections are the main causes of death in patients with MPNs and SC, and managed by supportive cancer care, such as anti-aggregant and antibiotic therapy [38]. In any case, a preceding MPN can be considered a predictor for poor outcomes in patients who develop new primary cancers [38]. Regarding the management of these patients, extra surveillance measures during follow-up may be considered in patients aged 60–79 years; systematic skin inspection and imaging analyses may be recommended, since a large proportion of SC are skin, kidney and lung cancers [38].

3. Possible Links between MPNs and SC

The pathogenic mechanisms responsible for the increased SC risk in MPNs have not been elucidated. Different hypotheses suggest the presence of shared genetic risk factors and an inherent tendency to develop cancer, or the effects of cytotoxic anti-neoplastic treatment, or else a possible link with chronic inflammation or immune dysfunction. All these aspects will be considered below.

3.1. Genetic Susceptibility

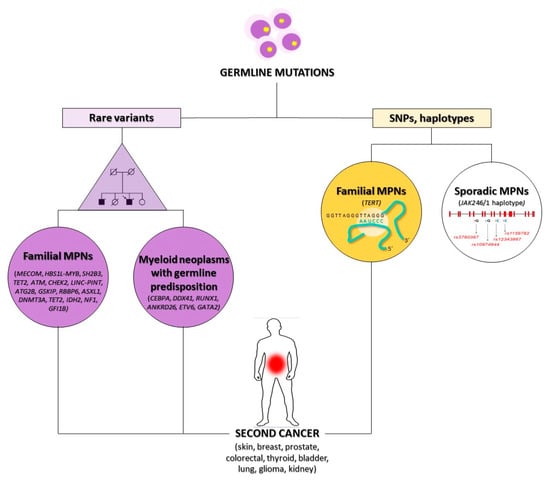

One possible molecular mechanism at the basis of the increased SC frequency in MPNs is a hereditary susceptibility to developing cancer that could confer an intrinsic predisposition even in untreated MPN patients [39]. Although somatic driver mutations cause the onset of MPNs in JAK2, CALR, and MPL genes or the BCR/ABL1 fusion gene in CML, several recent epidemiological studies revealed a crucial heritable component of the disease. In fact, first-degree relatives of patients with MPNs show a 5–7-fold increased risk of developing MPN compared to that observed in solid familial cancers like breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer [39,40]. Several genome-wide association (GWA) studies in MPN family clusters have identified many germline genetic variants associated with an increased risk of developing MPN. The strongest germline risk factors identified so far are the presence of the JAK2 46/1 haplotype and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene variants (Table 2), although these account for only a small fraction of familial MPN (Figure 1) [41]. The JAK2 46/1 haplotype, also referred to as “GGCC”, spans the JAK2 gene and is a “pre-JAK2” event predisposing to the acquisition of the JAK2 V617F mutation [42,43]. This haplotype accounted for a large proportion of sporadic MPNs, but does not account for a family predisposition, as this is not shared by all family members [44].

Table 2.

Main genes involved in the genetic susceptibility to SC onset in MPNs.

Figure 1.

Genetic susceptibility to SC onset in MPNs. The occurrence of rare (on the left) or polymorphic (on the right) germline mutations is one of the possible mechanisms connecting MPNs to an SC onset. SC: second cancer, MPNs: myeloproliferative neoplasms, SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms.

It is well known that abnormal telomerase activity plays a crucial role in the development of several cancers, and the TERT gene encodes a reverse transcriptase of the telomerase complex [9]. Mutations in the TERT gene can alter telomerase activity and telomere length, inducing bone marrow failure syndromes and significantly increasing cancer frequency [10]. Moreover, several SNPs located in exon or intron regions seem to influence telomere length and have been associated with the risk of different cancer types. The two most commonly studied SNP variants of the TERT gene are rs2736100 and rs2736098, which are related to the risk of both hematologic and solid cancers: rs2736100 was associated with an increased risk of thyroid, bladder, and lung cancer, glioma, and MPNs, whereas rs2736098 increased the risk of bladder and lung cancers. The TERT rs2736100 variant represents a germline predisposing factor with a non-specific effect on all MPNs, regardless of phenotype (PV, ET or PMF) or major molecular subtype such as the occurrence of JAK2 V617F or CALR gene mutations [10,45].

In several studies of GWAS, whole-exome sequencing (WES) or SNP arrays performed in MPN patients identified germline mutations or common genetic polymorphisms in multiple genes including MECOM, HBS1L-MYB, SH2B3 (LNK), TET2, ATM, CHEK2, LINC-PINT, ATG2B, GSKIP, RBBP6 and GFI1B, or epigenetic modifiers as ASXL1, DNMT3A, TET2, IDH2, and NF1 (Figure 1) [11,12,39,40,46]. These genes are involved in crucial cellular pathways regulating cell proliferation, differentiation or apoptosis and are also associated with a predisposition to several solid cancers [47,48,49].

Other genes that can predispose to the onset of either MPNs or solid cancers are included in the new WHO 2016 category of “Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition”, representing a rare but underdiagnosed entity whose recognition is recognized as critical for proper patient clinical management [50]. Patients and their family members should be closely monitored because they show an increased risk of non-hematopoietic malignancies and other organ dysfunctions. Myeloid neoplasms with germline predisposition are most frequently acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), more rarely other neoplasms such as CML, atypical CML (aCML), chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML) or PV and PMF. Mutated genes include CEBPA, DDX41, RUNX1, ANKRD26, ETV6, and GATA2, which are inherited in autosomal dominant patterns (Figure 1) [50,51].

The DDX41 gene encodes an RNA helicase protein involved in RNA splicing (Table 2) [52,53]. Multiple germline variants have been described, including frameshift, missense, and splicing mutations. Most patients with DDX41 mutations present an AML or MDS, but some cases are affected by CML or other MPNs, and some families also have a predisposition to immune disorders such as lupus, eczema, or vasculitis [52,53]. Some patients with a myeloid neoplasm and DDX41 germline mutations have a family history of solid cancers in first- or second-degree relatives or personal records of solid cancers, such as renal cell, prostate, and breast carcinoma [53].

The ETV6 missense mutations have a dominant-negative effect, resulting in a disrupted nuclear localization of the ETV6 transcription factor (Table 2) and the reduced expression of platelet-associated genes [54]. Families with germline ETV6 mutations most frequently developed B lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, MDS/AML, CMML, multiple myeloma, and PV [54]. A familial predisposition to solid tumors, including colorectal, breast, kidney, and skin cancer and meningioma was also observed [54].

The GATA2 gene encodes a zinc-finger transcription factor that is considered a master regulator of early hematopoiesis, as it plays a crucial role in the proliferation and maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Table 2) [55]. GATA2 expression is not limited to hematopoietic cells, but is also detected in endothelial, fetal liver and heart, placenta, and central nervous system cells [55]. GATA2 mutations can be either inherited or acquired, and due to the crucial role that GATA2 plays in the development and function of several cell lineages, almost all carriers of the mutation will probably develop hematologic or immunologic defects during their lifetime. GATA2 germline mutations have been reported in familial MDS and AML cases presenting at a younger age, and are also observed in individuals showing the “MonoMAC or DCML deficiency”, an immunodeficiency condition involving monocytes, CD4+ cells, dendritic cells, B and NK lymphoid cells and an increased risk of developing myeloid leukemia and mycobacterial, human papillomavirus (HPV) and opportunistic fungal infections [56]. GATA2 germline mutations are also detected in patients with “Emberger syndrome”, which is characterized by congenital deafness and lymphedema [56]. In individuals with GATA2 germline mutations, the onset of a malignant disease is common, frequently due to HPV-driven intraepithelial neoplasia but an increase in breast cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, and neoplasms correlated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection has also been reported [56]. A recent report described a patient with a JAK2V617F-positive PMF and an inherited GATA2 mutation who developed a basal cell carcinoma of the facial skin six years after the initial diagnosis and therapy with the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib [57]. The patient showed the germline GATA2-N317S missense mutation previously reported in MDS and AML patients but not in cases with GATA2-deficiency syndrome [57]. Patients with a germline GATA2 mutation are known to be at increased risk for skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma [57]. In this patient, the GATA2 mutation preceded the acquisition of the JAK2V617F mutation causing the PMF onset [57].

Moreover, it has been hypothesized that CML patients have an inborn increased predisposition to develop secondary malignancies [58]. CML patients show a high risk of developing an SC such as gastrointestinal and nose and throat tumors. However, it has been hypothesized that the augmented incidence may be linked to CML itself, as the prevalence of malignancies and autoimmune diseases is increased in CML patients before their CML diagnosis [58]. These data suggest that a hereditary or acquired predisposition to cancer and immune dysfunction could be involved in the CML pathogenesis.

3.2. Effect of Cytotoxic Drugs

Undoubtedly, one of the most evident links between MPNs and SC is the cytotoxic effect of treatment [4,5,13]. In 2019, an international nested case–control study (involving 30 centers) was conducted, aiming to evaluate the risk of SC after exposure to cytoreductive drugs, in a cohort of 1881 Philadelphia-negative MPNs [4]. The administration of hydroxyurea (HU), pipobroman, ruxolitinib and their combination showed an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancers onset compared with unexposed patients [4]. Notably, very recent studies showed the higher incidence of SC in the post-ruxolitinib era [59], in both PV and myelofibrosis patients [60,61]. Conversely, no association with the risk of overall SC was observed after exposure to interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha), busulfan and anagrelide [4]. Regarding the probability of leukemic conversion, chlorambucil, phosphorus-32 (32P) and pipobroman were the MPN therapies showing the highest risk [62].

Among the drugs mentioned above, HU is the most frequently used cytoreductive agent (due to its perceived efficacy and tolerability), and its mode of action is worthy of discussion [62]. HU is an anti-metabolite agent inhibiting the enzymatic activity of ribonucleotide reductase, thereby inactivating DNA synthesis [62]. HU inhibits DNA synthesis and DNA repair (Table 1). In fact, it increases the number of DNA breaks, causing the strands to remain open longer, and decreases the DNA polymerase activity, thereby slowing the polymerization rate at the repair sites [13,14]. Furthermore, HU and exposure to UV radiation play a combined role in skin cancers onset; in fact, UV-B rays promote the proliferation of TP53 mutant keratinocytes (seen in the dermo-epidermal junction and hair follicles) and enable them to colonize the adjacent compartment [15,16]. In the basal layer of the epidermis, the high keratinocyte turnover with HU impaired DNA synthesis and repair are the causes of skin tumors onset [61]. For these reasons, during HU administration, patients should avoid excessive sunlight exposure and use chemopreventive agents like oral retinoids [63,64].

Moreover, HU administration was shown to be linked to the occurrence of PPM1D truncating mutations. Together with TP53, PPM1D is another DNA repair gene whose variants onset is widely associated with prior chemotherapy exposure (Table 1) [17,18].

As regards drugs cytotoxicity, use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is noteworthy. TKI administration is frequently prolonged for decades, and the risk of SC is higher in the CML than the expected rates in the rest of the population [65,66]. Nevertheless, these neoplasms are unlikely to manifest until after several years of treatment [65]. On the contrary, the SC standardized incidence ratio was the same before and two years after diagnosis, suggesting that it is not TKI treatment that causes the increased number of SC, but rather the CML disease itself [65,67]. Therefore, there is no current evidence supporting a link between TKI exposure and the risk of developing SC.

3.3. Influence of Chronic Inflammation

Several decades ago, Virchow established a link between inflammation and malignancies, and many cellular and molecular circuits have been described over the years [68,69,70]. MPNs are characterized by a state of chronic inflammation (CI), which is proposed to be the common denominator for premature atherosclerosis onset, clonal evolution, and SC development [30]. MPNs can be considered as a “Human Inflammation Model” since the disease per se produces a state of CI due to the continuous release of inflammatory molecules from activated leukocytes and platelets [19,30,71]. Increasing release of cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxygen species (ROS) gives rise to genetic and epigenetic changes, inducing genomic instability, which thereby contributes to tumor initiation (Table 1) [19]. IL-6, IL-1b, TNF-alpha and ROS are the main factors inducing DNA methylation changes [23,24,25]. Moreover, oxidative DNA damage implies an increased risk of mutagenesis [20,21]. Furthermore, inflammatory mediators activate transcription factors such as NF-KB and STAT3, associated with an altered expression of several genes and then playing major roles in linking inflammation and carcinogenesis (Table 1) [22,72].

In recent years, the ability of inflammation to induce clonal hematopoiesis (CH) has been amply demonstrated [26]. In particular, in vitro, Tet2-deficient murine and TET2-mutant human hematopoietic stem cells have a strong proliferative advantage compared with wild-type cells when exposed to high levels of exogenous, pro-inflammatory IL-6 and TNF-α (Table 1) [27,28]. CH is associated with an approximately tenfold increased risk (or higher risk with larger clones) of future hematological cancers, mainly MDS and AML [73,74]. Furthermore, CH is now understood to be a risk factor for therapy-related myeloid neoplasms [75]. Among the main CH-related genes, DNMT3A and TET2 have a clear functional role in supporting cancer development [76,77]. It is, therefore, reasonable to suppose that in the inflammatory context of MPNs, CH onset could pave the way for a second hematological cancer.

Lastly, the inflammatory milieu may induce immune deregulation and then a defective tumor immune surveillance, favoring the occurrence of an SC, but this scenario warrants separate discussion [78,79,80,81].

3.4. Immune Deregulation

The defective tumor immune surveillance observed in MPNs is a bridge mechanism between the above-described aspects; in fact, all the scenarios presented can, in different ways, affect the immune system ability to conduct surveillance and sense the onset of an SC in MPN patients.

The off-target immunological effect of TKI is an emblematic example: several in vitro studies and animal models show how imatinib can affect the function and differentiation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and inhibit the effector functions of T lymphocytes [78,79]. Moreover, the induction of specific cytotoxic T cells seems to be impaired in CML patients treated with imatinib compared with patients receiving IFN-alpha [78]. Another representative example is the NF-KB pathway, which has a key role in inflammation and innate immunity and promotes tumor development [80].

Nevertheless, in MPNs, regardless of drug administration or CI, the release of immunosuppressive cytokines such as VEGF and TGF-beta may be critical for the increased risk of SC development [29]. In fact, both cytokines induced qualitative and quantitative alterations in immune cells that are essential for tumor immune surveillance (e.g., dendritic cells (DCs), cytotoxic T cells, regulatory T cells (T-reg), and natural killer (NK) cells) (Table 1) [30,31].

VEGF mediates the induction and maintenance of CD4(+)CD25 (high) T cells (T-reg), immune cells with a high immunosuppressive power [32]. TGF-beta affects T lymphocytes and APCs, reducing the IL-2–dependent proliferation of T cells by blocking IL-2 production, inhibiting the maturation of T cells and preventing naive T lymphocytes from acquiring effector functions [33,34]. TGF-beta also has potent effects on professional APCs, inhibiting tissue macrophage activation and promoting DCs differentiation from precursors [33,35,36].

Last but not least, signs of immune deregulation and CI were also observed in the gene expression profile of MPNs. In fact, 123 differentially expressed genes involved in these mechanisms were identified in ET, PV and PMF peripheral blood cells, such as IL-4, ITGB3, TNFAIP8L1, SELPLG, CREB1, LSP1, IL1A, FAS (Table 1) [37].

These observations support the use of immune-enhancing therapy in MPNs, aimed at restoring the defective tumor immune surveillance system [29]. IFN-alpha shows this ability to act on crucial immune cells (T cells, DCs and NK cells) involved in these processes and may potentially reduce the increased risk of SC in MPNs [81].

4. Conclusions

From the hematologist’s point of view, SC onset in MPNs is one of the risks the patient can run during follow-up, whose occurrence affects the clinical course of the disease. On the contrary, from the oncologist’s point of view, a previous MPN is considered predictive poor outcomes in patients who develop a new primary cancer. In both cases, the patient needs dedicated management considering the co-occurrence of two neoplasms in the same individual.

Regardless of the direction from which the scenario is observed, the mechanisms linking the two events are the same and more care and investigation needs to be devoted to better elucidating them.

In fact, not all MPNs without distinction show the same risk of developing an SC; not all genetic backgrounds predispose equally to these events and not all therapeutic approaches increase the risk in the same way. These considerations underline the need for a personalized evaluation of each case, searching for the most likely molecular (or cellular) pathways linking the two neoplasms.

A more comprehensive biological knowledge of this fascinating and incomplete picture is necessary, particularly probing emerging aspects such as CH onset and potential. New perspectives could emerge from this widely studied topic but even offering open questions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C., L.A. and F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C., L.A., A.Z., N.C., F.T., G.S., P.M. and F.A.; writing—review and editing, C.C., L.A. and F.A.; supervision, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by “Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie (AIL)-BARI”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| MPNs | myeloproliferative neoplasms |

| PV | polycythemia vera |

| ET | essential thrombocythemia |

| PMF | primary myelofibrosis |

| CML | chronic myeloid leukemia |

| SC | second cancer |

| GWA | genome-wide association |

| WES | whole exome sequencing |

| AML | acute myeloid leukemia |

| MDS | myelodysplastic syndromes |

| aCML | atypical CML |

| CMML | chronic myelomonocytic leukemia |

| HSCs | hematopoietic stem cells |

| HPV | human papillomavirus |

| IFN-alpha | interferon-alpha |

| 32P | phosphorus-32 |

| CI | chronic inflammation |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| APCs | antigen presenting cells |

| DCs | dendritic cells |

| T-reg | regulatory T cells |

| NK | natural killer |

References

- Grinfeld, J.; Nangalia, J.; Baxter, E.J.; Wedge, D.C.; Angelopoulos, N.; Cantrill, R.; Godfrey, A.L.; Papaemmanuil, E.; Gundem, G.; MacLean, C.; et al. Classification and Personalized Prognosis in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1416–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultcrantz, M.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Andersson, T.M.L.; Landgren, O.; Eloranta, S.; Derolf, Å.R.; Dickman, P.W.; Björkholm, M. Patterns of survival among patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2008: A population-based study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2995–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landtblom, A.R.; Bower, H.; Andersson, T.M.L.; Dickman, P.W.; Samuelsson, J.; Björkholm, M.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Hultcrantz, M. Second malignancies in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: A population-based cohort study of 9379 patients. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2203–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbui, T.; Ghirardi, A.; Masciulli, A.; Carobbio, A.; Palandri, F.; Vianelli, N.; De Stefano, V.; Betti, S.; Di Veroli, A.; Iurlo, A.; et al. Second cancer in Philadelphia negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN-K). A nested case-control study. Leukemia 2019, 33, 1996–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Zheng, G.; Sud, A.; Yu, H.; Sundquist, K.; Sundquist, J.; Försti, A.; Hemminki, A.; Houlston, R.; Hemminki, K. Risk of second primary cancer following myeloid neoplasia and risk of myeloid neoplasia as second primary cancer: A nationwide, observational follow up study in Sweden. Lancet Haematol. 2018, 5, e368–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, H.; Farkas, D.K.; Christiansen, C.F.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Sørensen, H.T. Chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and subsequent cancer risk: A Danish population-based cohort study. Blood 2011, 118, 6515–6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, B.; Rumi, E.; Guglielmelli, P.; Barraco, D.; Maffioli, M.; Rambaldi, A.; Caramella, M.; Komrokji, R.; Gotlib, J.; Kiladjian, J.J.; et al. Second primary malignancies in postpolycythemia vera and postessential thrombocythemia myelofibrosis: A study on 2233 patients. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 4089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabrand, M.; Frederiksen, H. Risks of solid and lymphoid malignancies in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms: Clinical implications. Cancers 2020, 12, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco, M.A. Telomeres and human disease: Ageing, cancer and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005, 6, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddsson, A.; Kristinsson, S.Y.; Helgason, H.; Gudbjartsson, D.F.; Masson, G.; Sigurdsson, A.; Jonasdottir, A.; Jonasdottir, A.; Steingrimsdottir, H.; Vidarsson, B.; et al. The germline sequence variant rs2736100_C in TERT associates with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Leukemia 2014, 28, 1371–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, D.A.; Barnholt, K.E.; Mesa, R.A.; Kiefer, A.K.; Do, C.B.; Eriksson, N.; Mountain, J.L.; Francke, U.; Tung, J.Y.; Nguyen, H.; et al. Germ line variants predispose to both JAK2 V617F clonal hematopoiesis and myeloproliferative neoplasms. Blood 2016, 128, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper, W.; Jones, A.V.; Kralovics, R.; Harutyunyan, A.S.; Zoi, K.; Leung, W.; Godfrey, A.L.; Guglielmelli, P.; Callaway, A.; Ward, D.; et al. Genetic variation at MECOM, TERT, JAK2 and HBS1L-MYB predisposes to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malato, A.; Rossi, E.; Palumbo, G.A.; Guglielmelli, P.; Pugliese, N. Drug-related cutaneous adverse events in philadelphia chromosome-negative myeloproliferative neoplasms: A literature review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erixon, K.; Ahnström, G. Single-strand breaks in DNA during repair of UV-induced damage in normal human and xeroderma pigmentosum cells as determined by alkaline DNA unwinding and hydroxylapatite chromatography: Effects of hydroxyurea, 5-fluorodeoxyuridine and 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine on the kinetics of repair. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1979, 59, 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Gavini, D.R.; Salvi, D.J.; Shah, P.H.; Uma, D.; Lee, J.H.; Hamid, P. Non-melanoma Skin Cancers in Patients on Hydroxyurea for Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2021, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Remenyik, E.; Zelterman, D.; Brash, D.E.; Wikonkal, N.M. Escaping the stem cell compartment: Sustained UVB exposure allows p53-mutant keratinocytes to colonize adjacent epidermal proliferating units without incurring additional mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 13948–13953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, C.C.; Zehir, A.; Devlin, S.M.; Kishtagari, A.; Syed, A.; Jonsson, P.; Hyman, D.M.; Solit, D.B.; Robson, M.E.; Baselga, J.; et al. Therapy-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis in Patients with Non-hematologic Cancers Is Common and Associated with Adverse Clinical Outcomes. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 21, 374–382.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.D.; Miller, P.G.; Silver, A.J.; Sellar, R.S.; Bhatt, S.; Gibson, C.; McConkey, M.; Adams, D.; Mar, B.; Mertins, P.; et al. PPM1D-truncating mutations confer resistance to chemotherapy and sensitivity to PPM1D inhibition in hematopoietic cells. Blood 2018, 132, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. Chronic inflammation as a promotor of mutagenesis in essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera and myelofibrosis. A human inflammation model for cancer development? Leuk. Res. 2013, 37, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, L.R. Chronic inflammation and mutagenesis. Mutat. Res. 2010, 690, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.S.; Evans, M.D.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Lunec, J. Oxidative DNA damage: Mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J. 2003, 17, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Karin, M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010, 21, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, M.A.; Hahn, T.; Lee, D.H.; Esworthy, R.S.; Kim, B.W.; Riggs, A.D.; Chu, F.F.; Pfeifer, G.P. Methylation of polycomb target genes in intestinal cancer is mediated by inflammation. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 10280–10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foran, E.; Garrity-Park, M.M.; Mureau, C.; Newell, J.; Smyrk, T.C.; Limburg, P.J.; Egan, L.J. Upregulation of DNA methyltransferase-mediated gene silencing, anchorage-independent growth, and migration of colon cancer cells by interleukin-6. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010, 8, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hagan, H.M.; Wang, W.; Sen, S.; DeStefano Shields, C.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Clements, E.G.; Cai, Y.; Van Neste, L.; Easwaran, H.; et al. Oxidative damage targets complexes containing DNA methyltransferases, SIRT1, and polycomb members to promoter CpG Islands. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.K.; Luo, M.; Rauh, M.J. Clonal hematopoiesis and inflammation: Partners in leukemogenesis and comorbidity. Exp. Hematol. 2020, 83, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegunde, S.O.; Buckstein, R.; Wells, R.A.; Rauh, M.J. An inflammatory environment containing TNFα favors Tet2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 2018, 59, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Kotzin, J.J.; Ramdas, B.; Chen, S.; Nelanuthala, S.; Palam, L.R.; Pandey, R.; Mali, R.S.; Liu, Y.; Kelley, M.R.; et al. Inhibition of Inflammatory Signaling in Tet2 Mutant Preleukemic Cells Mitigates Stress-Induced Abnormalities and Clonal Hematopoiesis. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 23, 833–849.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. Perspectives on the increased risk of second cancer in patients with essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera and myelofibrosis. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 94, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. Perspectives on chronic inflammation in essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis: Is chronic inflammation a trigger and driver of clonal evolution and development of accelerated atherosclerosis and second cancer? Blood 2012, 119, 3219–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. The role of cytokines in the initiation and progression of myelofibrosis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, J.; Suauki, H.; Fuchino, R.; Yamasaki, A.; Nagai, S.; Yanai, K.; Koga, K.; Nakamura, M.; Tanaka, M.; Morisaki, T.; et al. The Contribution of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor to the Induction of Regulatory T-Cells in Malignant Effusions. Anticancer Res. 2009, 29, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Blobe, G.C. Role of transforming growth factor-β in hematologic malignancies. Blood 2006, 107, 4589–4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorelik, L.; Flavell, R.A. Transforming growth factor-beta in T-cell biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, E.; Strobl, H.; Majdic, O.; Knapp, W. TGF-beta 1 promotes in vitro generation of dendritic cells by protecting progenitor cells from apoptosis. J. Immunol. 1997, 158, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bogdans, C.; Paik, J.; Vodovotz, Y.; Nathan, C. Contrasting Mechanisms for Suppression of Macrophage Cytokine Release by Transforming Growth Factor-@ and Interleukin-10. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 23301–23308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skov, V.; Larsen, T.S.; Thomassen, M.; Riley, C.H.; Jensen, M.K.; Bjerrum, O.W.; Kruse, T.A.; Hasselbalch, H.C. Molecular profiling of peripheral blood cells from patients with polycythemia vera and related neoplasms: Identification of deregulated genes of significance for inflammation and immune surveillance. Leuk. Res. 2012, 36, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, H.; Farkas, D.K.; Christiansen, C.F.; Larsen, T.S.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Stentoft, J.; Sørensen, H.T. Survival of patients with chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms and new primary cancers: A population-based cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2015, 2, e289–e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bao, E.L.; Nandakumar, S.K.; Liao, X.; Bick, A.G.; Karjalainen, J.; Tabaka, M.; Gan, O.I.; Havulinna, A.S.; Kiiskinen, T.T.J.; Lareau, C.A.; et al. Inherited myeloproliferative neoplasm risk affects haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2020, 586, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumi, E.; Cazzola, M. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of familial myeloproliferative neoplasms. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 178, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Mei, H.; Peng, L.; Li, X.; Tang, J. The TERT rs2736100 polymorphism increases cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38693–38705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anelli, L.; Orsini, P.; Zagaria, A.; Minervini, A.; Coccaro, N.; Parciante, E.; Minervini, C.F.; Cumbo, C.; Tota, G.; Impera, L.; et al. Erythrocytosis with JAK2 GGCC_46/1 haplotype and without JAK2 V617F mutation is associated with CALR rs1049481_G allele. Leukemia 2020, 35, 619–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Specchia, G.; Albano, F. The JAK2 GGCC (46/1) Haplotype in Myeloproliferative Neoplasms: Causal or Random? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.V.; Chase, A.; Silver, R.T.; Oscier, D.; Zoi, K.; Wang, Y.L.; Cario, H.; Pahl, H.L.; Collins, A.; Reiter, A.; et al. JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nat. Genet. 2009, 41, 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifa, A.P.; Bănescu, C.; Tevet, M.; Bojan, A.; Dima, D.; Urian, L.; Török-Vistai, T.; Popov, V.M.; Zdrenghea, M.; Petrov, L.; et al. TERT rs2736100 A>C SNP and JAK2 46/1 haplotype significantly contribute to the occurrence of JAK2 V617F and CALR mutated myeloproliferative neoplasms—A multicentric study on 529 patients. Br. J. Haematol. 2016, 174, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Swierczek, S.I.; Drummond, J.; Hickman, K.; Kim, S.; Walker, K.; Doddapaneni, H.; Muzny, D.M.; Gibbs, R.A.; Wheeler, D.A.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing of polycythemia vera revealed novel driver genes and somatic mutation shared by T cells and granulocytes. Leukemia 2014, 28, 935–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbita, Z.; Meyer, M.; Skepu, A.; Hosie, M.; Rees, J.; Dlamini, Z. De-regulation of the RBBP6 isoform 3/DWNN in human cancers. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 362, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarova, L.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Soukupova, J.; Zemankova, P.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. CHEK2 Germline Variants in Cancer Predisposition: Stalemate Rather than Checkmate. Cells 2020, 9, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Yin, Z.H.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Zhou, B. Sen Association between ATM polymorphisms and cancer risk:a meta-analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 5719–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.; Thiele, J.; Borowitz, M.J.; Le Beau, M.M.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Cazzola, M.; Vardiman, J.W. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016, 127, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crysandt, M.; Brings, K.; Beier, F.; Thiede, C.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Jost, E. Germ line predisposition to myeloid malignancies appearing in adulthood. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2018, 11, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada, A.E.; Routbort, M.J.; DiNardo, C.D.; Bueso-Ramos, C.E.; Kanagal-Shamanna, R.; Khoury, J.D.; Thakral, B.; Zuo, Z.; Yin, C.C.; Loghavi, S.; et al. DDX41 mutations in myeloid neoplasms are associated with male gender, TP53 mutations and high-risk disease. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, T.; Tu, Z.J.; Wang, Z.; Cook, J.R. Clinical and Pathologic Spectrum of DDX41-Mutated Hematolymphoid Neoplasms. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, J.T. Myeloid Neoplasms with Germline Predisposition. Pathobiology 2019, 86, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarski, M.W.; Collin, M.; Horwitz, M.S. GATA2 deficiency and related myeloid neoplasms. Semin. Hematol. 2017, 54, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M.; Dickinson, R.; Bigley, V. Haematopoietic and immune defects associated with GATA2 mutation. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rütsche, C.V.; Haralambieva, E.; Lysenko, V.; Balabanov, S.; Theocharides, A.P.A. A patient with a germline GATA2 mutation and primary myelofibrosis. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnarsson, N.; Höglund, M.; Stenke, L.; Wallberg-Jonsson, S.; Sandin, F.; Björkholm, M.; Dreimane, A.; Lambe, M.; Markevärn, B.; Olsson-Strömberg, U.; et al. Increased prevalence of prior malignancies and autoimmune diseases in patients diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2016, 30, 1562–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.W.; Jamy, O.; Shah, M.V.; Vachhani, P.; Go, R.S.; Goyal, G. Risk of mortality and second malignancies in primary myelofibrosis before and after ruxolitinib approval. Leuk. Res. 2022, 112, 106770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhri, R.; Sadjadian, P.; Becker, T.; Kolatzki, V.; Huenerbein, K.; Meixner, R.; Marchi, H.; Wallmann, R.; Fuchs, C.; Griesshammer, M.; et al. Ruxolitinib-treated polycythemia vera patients and their risk of secondary malignancies. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 2707–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polverelli, N.; Elli, E.M.; Abruzzese, E.; Palumbo, G.A.; Benevolo, G.; Tiribelli, M.; Bonifacio, M.; Tieghi, A.; Caocci, G.; D’Adda, M.; et al. Second primary malignancy in myelofibrosis patients treated with ruxolitinib. Br. J. Haematol. 2021, 193, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbert, D.; Stein, B.L. Therapy-associated leukemic transformation in myeloproliferative neoplasms—What do we know? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2019, 32, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantisani, C.; Kiss, N.; Naqeshbandi, A.F.; Tosti, G.; Tofani, S.; Cartoni, C.; Carmosino, I.; Cantoresi, F. Nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with Hydroxyurea treatment: Overview of the literature and our own experience. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 32, e13043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulte, C.A.; Hoegler, K.M.; Kutlu, Ö.; Khachemoune, A. Hydroxyurea: A reappraisal of its cutaneous side effects and their management. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021, 60, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunnarsson, N.; Stenke, L.; Höglund, M.; Sandin, F.; Björkholm, M.; Dreimane, A.; Lambe, M.; Markevärn, B.; Olsson-Strömberg, U.; Richter, J.; et al. Second malignancies following treatment of chronic myeloid leukaemia in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era. Br. J. Haematol. 2015, 169, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Kantarjian, H.; Strom, S.S.; Rios, M.B.; Jabbour, E.; Quintas-Cardama, A.; Verstovsek, S.; Ravandi, F.; O’Brien, S.; Cortes, J. Malignancies occurring during therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and other hematologic malignancies. Blood 2011, 118, 4353–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliotta, G.; Castagnetti, F.; Breccia, M.; Albano, F.; Iurlo, A.; Intermesoli, T.; Abruzzese, E.; Levato, L.; D’Adda, M.; Pregno, P.; et al. Incidence of second primary malignancies and related mortality in patients with imatinib-treated chronic myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 2017, 102, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.P.; Harris, C.C. Inflammation and cancer: An ancient link with novel potentials. Int. J. Cancer 2007, 121, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Garlanda, C.; Allavena, P. Molecular pathways and targets in cancer-related inflammation. Ann. Med. 2010, 42, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbui, T.; Carobbio, A.; Finazzi, G.; Vannucchi, A.M.; Barosi, G.; Antonioli, E.; Guglielmelli, P.; Pancrazzi, A.; Salmoiraghi, S.; Zilio, P.; et al. Inflammation and thrombosis in essential thrombocythemia and polycythemia vera: Different role of C-reactive protein and pentraxin 3. Haematologica 2011, 96, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumbo, C.; Tarantini, F.; Anelli, L.; Zagaria, A.; Redavid, I.; Minervini, C.F.; Coccaro, N.; Tota, G.; Ricco, A.; Parciante, E.; et al. IRF4 expression is low in Philadelphia negative myeloproliferative neoplasms and is associated with a worse prognosis. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, G.; Kähler, A.K.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lindberg, J.; Rose, S.A.; Bakhoum, S.F.; Chambert, K.; Mick, E.; Neale, B.M.; Fromer, M.; et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2477–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Fontanillas, P.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.; Grauman, P.V.; Mar, B.G.; Lindsley, R.C.; Mermel, C.H.; Burtt, N.; Chavez, A.; et al. Age-Related Clonal Hematopoiesis Associated with Adverse Outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 2488–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Wang, F.; Kantarjian, H.; Doss, D.; Khanna, K.; Thompson, E.; Zhao, L.; Patel, K.; Neelapu, S.; Gumbs, C.; et al. Preleukaemic clonal haemopoiesis and risk of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms: A case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, A.; Yang, L.; Rodriguez, B.; Zhou, T.; Chang, E.; Curry, C.V.; Challen, G.A.; Li, W.; Wheeler, D.; Rebel, V.I.; et al. Dnmt3a loss predisposes murine hematopoietic stem cells to malignant transformation. Blood 2015, 125, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Crusio, K.; Reavie, L.; Shih, A.; Abdel-Wahab, O.; Ndiaye-Lobry, D.; Lobry, C.; Figueroa, M.E.; Vasanthakumar, A.; Patel, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Tet2 Loss Leads to Increased Hematopoietic Stem Cell Self-Renewal and Myeloid Transformation. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, S.; Balabanov, S.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; Brossart, P. Effects of Imatinib on Normal Hematopoiesis and Immune Activation. Stem Cells 2005, 23, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Rusakiewicz, S.; Routy, B.; Ayyoub, M.; Kroemer, G. Immunological off-target effects of imatinib. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Verma, I.M. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbalch, H.C. A new era for IFN-α in the treatment of Philadelphia-negative chronic myeloproliferative neoplasms. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2011, 4, 637–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).