Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Dysregulation of Gene Expression and Lipid Metabolism in HIV+ Patients: Beneficial Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals

Abstract

1. Introduction

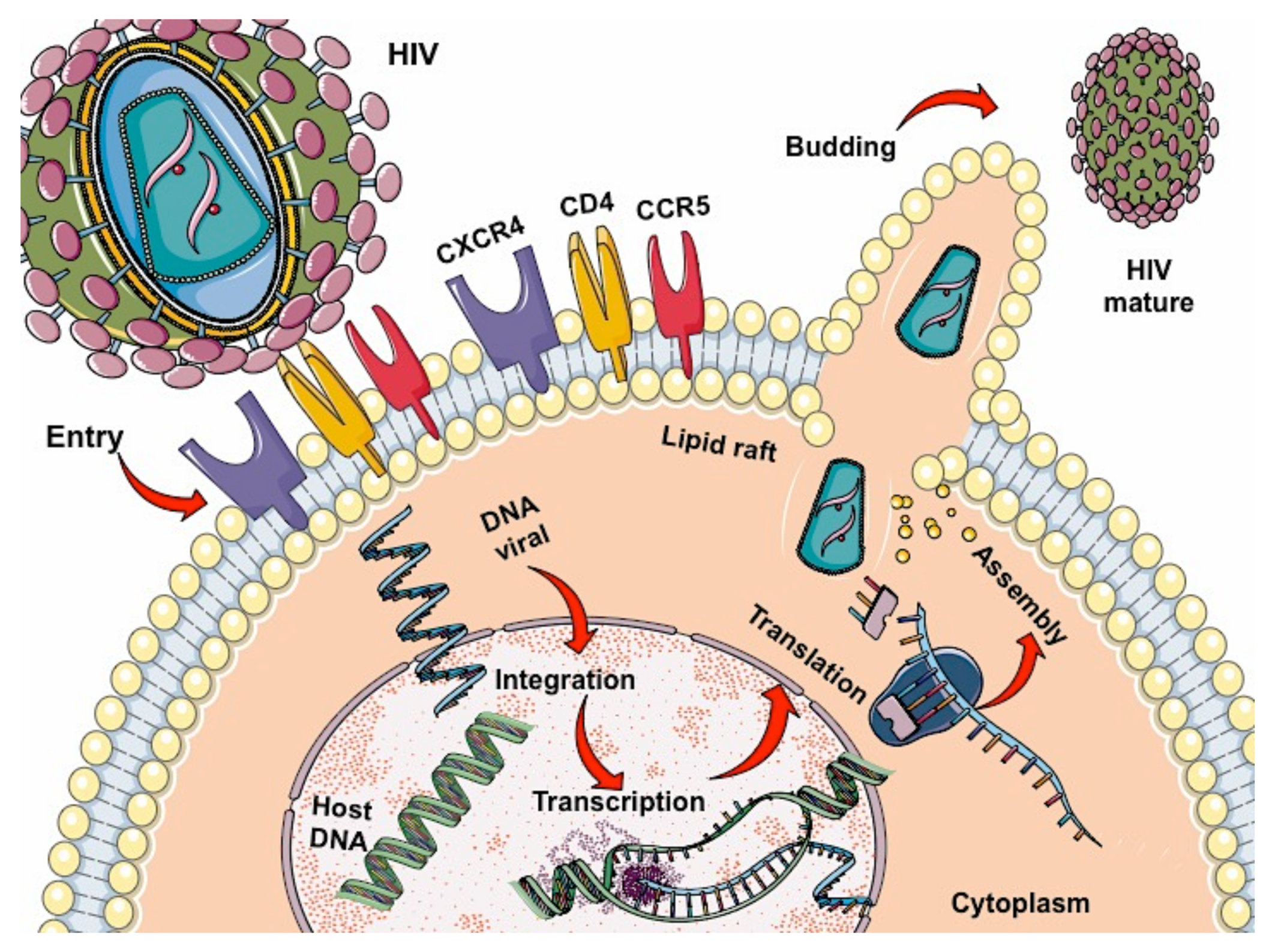

2. HIV

2.1. Antiretroviral Therapy (ART)

2.1.1. Proteases Inhibitors

2.1.2. Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs)

2.1.3. Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs)

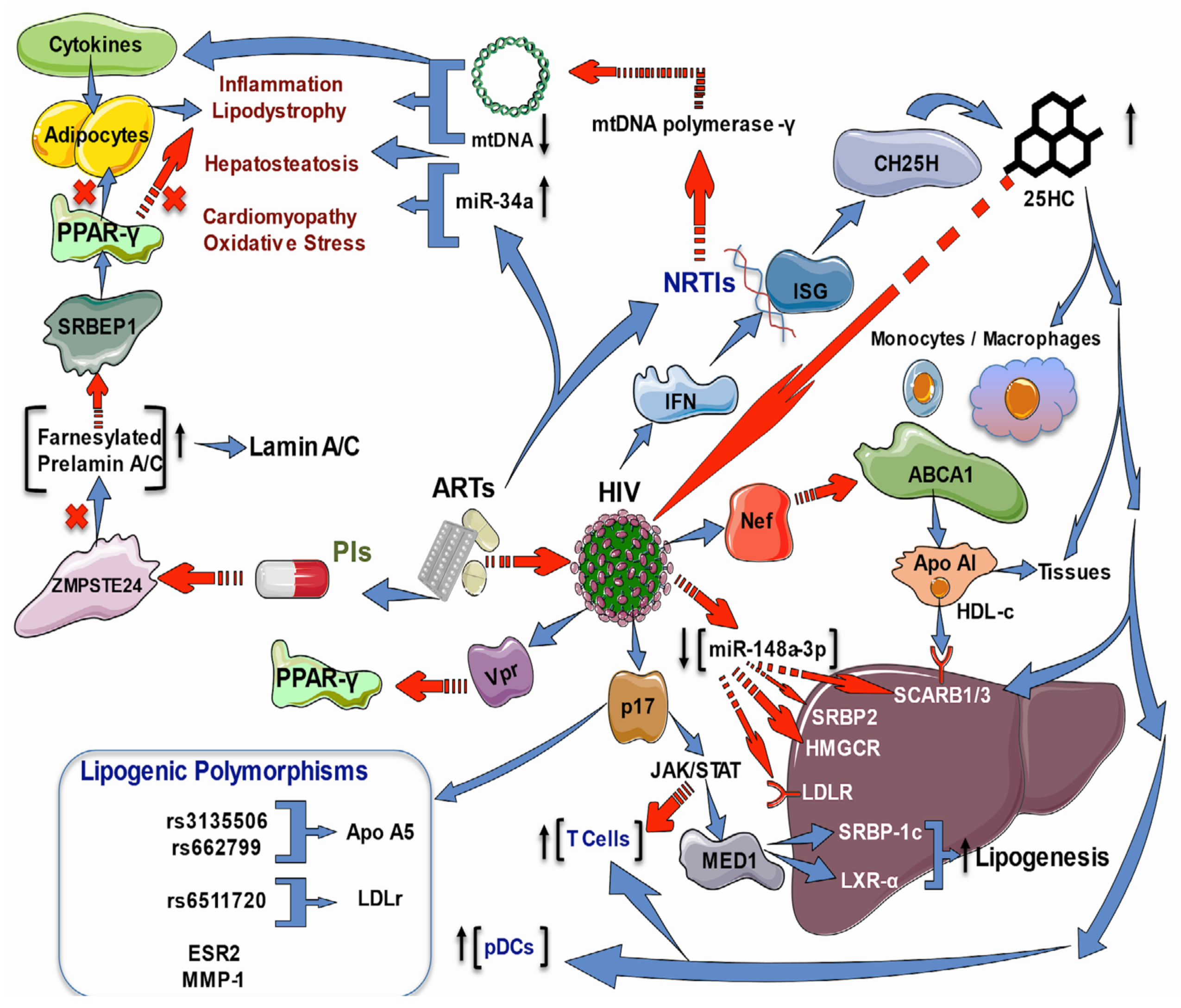

2.2. Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy on Lipid and Cholesterol Metabolism

2.3. Effects of HIV Infection and ART on Lipid and Cholesterol Genes

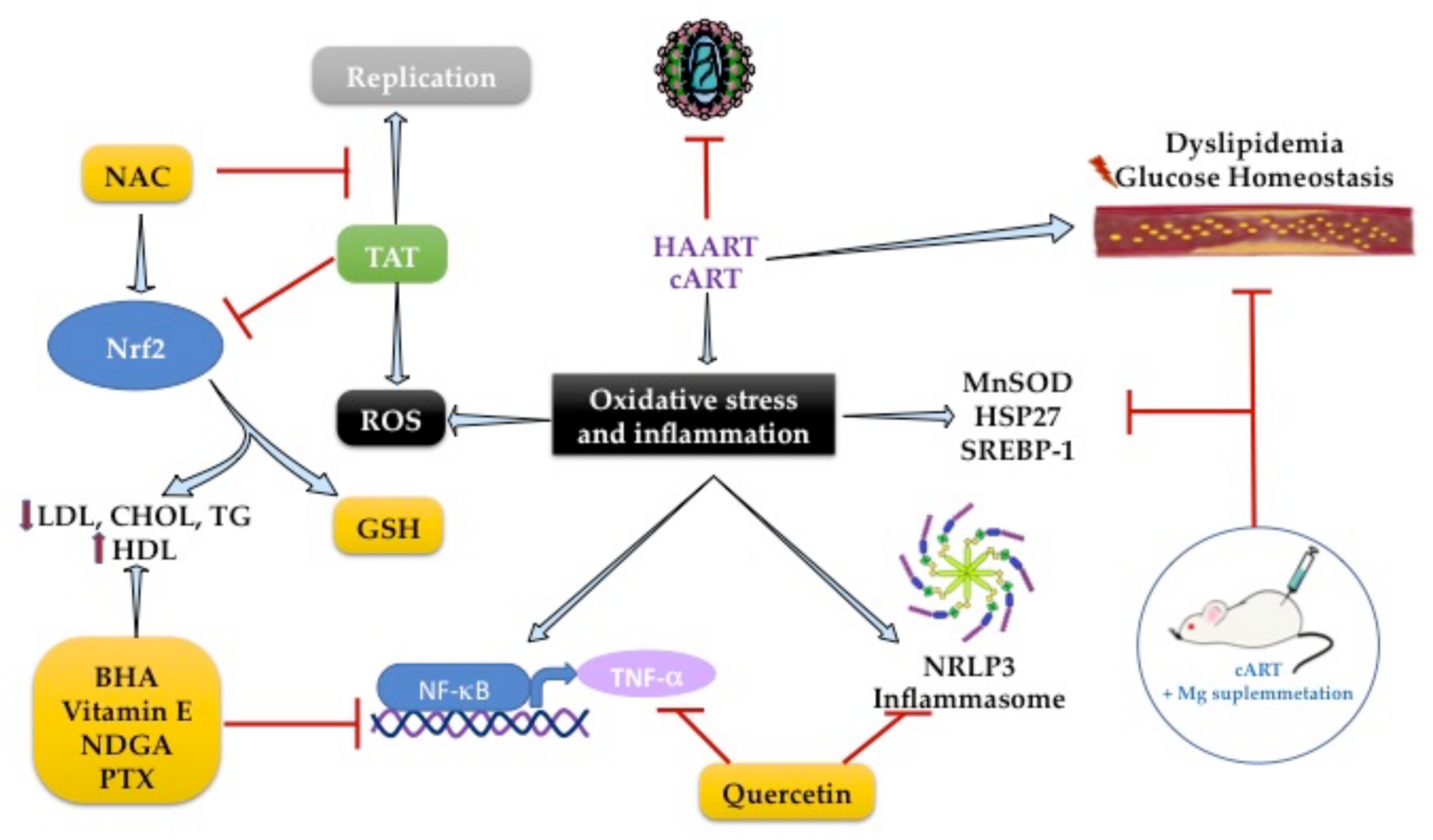

2.4. Increased Oxidative Stress in People HIV+

2.5. Antioxidants and Phytochemicals

2.5.1. Vitamin A

2.5.2. Carotenoids

2.5.3. Flavonoids

2.5.4. Ellagic Acid

2.6. Role of Antioxidants on Lipid Metabolism during HIV Infection

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lot, F.; Cazein, F. Épidémiologie Du VIH et Situation Chez Les Seniors. Soins 2019, 64, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.S.; Wilkin, T.J.; Shalev, N.; Hammer, S.M. CROI 2013: Advances in Antiretroviral Therapy. Top. Antivir. Med. 2013, 21, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blas-Garcia, A.; Apostolova, N.; Esplugues, J.V. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Impairment After Treatment with Anti-HIV Drugs: Clinical Implications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 4076–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, A.V.; Valuev-Elliston, V.T.; Ivanova, O.N.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Starodubova, E.S.; Bartosch, B.; Isaguliants, M.G. Oxidative Stress during HIV Infection: Mechanisms and Consequences. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 8910396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chettimada, S.; Lorenz, D.R.; Misra, V.; Dillon, S.T.; Reeves, R.K.; Manickam, C.; Morgello, S.; Kirk, G.D.; Mehta, S.H.; Gabuzda, D. Exosome Markers Associated with Immune Activation and Oxidative Stress in HIV Patients on Antiretroviral Therapy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative Stress: A Concept in Redox Biology and Medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoner, T.; Dichtl, W. Oxidative Stress in Cardiovascular Diseases: Still a Therapeutic Target? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, I. Update on the Molecular Biology of Dyslipidemias. Clin. Chim. Acta 2016, 454, 143–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Jiménez, J.G.; Roura-Guiberna, A.; Jiménez-Mena, L.R.; Olivares-Reyes, J.A. El Papel de Los Ácidos Grasos Libres En La Resistencia a La Insulina. Gac. Med. Mex. 2017, 153, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioga, E.A.M.; Arias-de la Torre, J.; Patera, E.; Borjabad, B.; Macorigh, L.; Ferrer, L. El Papel de Las Intervenciones Biomédicas En La Prevención Del VIH: La Profilaxis Preexposición (PrEP). Med. Fam. SEMERGEN 2020, 46, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musisi, E.; Matovu, D.K.; Bukenya, A.; Kaswabuli, S.; Zawedde, J.; Andama, A.; Byanyima, P.; Sanyu, I.; Sessolo, A.; Seremba, E.; et al. Effect of Anti-Retroviral Therapy on Oxidative Stress in Hospitalized HIV-Infected Adults with and without TB. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mburu, S.; Marnewick, J.L.; Abayomi, A.; Ipp, H. Modulation of LPS-Induced CD4+ T-Cell Activation and Apoptosis by Antioxidants in Untreated Asymptomatic HIV Infected Participants: An In Vitro Study. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 2013, 631063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Fernández, L.; Fiestas, F.; Vásquez, R.; Benites, C. Tratamiento Anti-Retroviral Conteniendo Raltegravir En Mujeres Gestantes Con Infección Por VIH: Revisión Sistemática. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2016, 33, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogineni, V.; Schinazi, R.F.; Hamann, M.T. Role of Marine Natural Products in the Genesis of Antiviral Agents. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9655–9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B.; Kumar, N.V.A.; Şener, B.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kılıç, M.; Mahady, G.B.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Iriti, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Setzer, W.N.; et al. Medicinal Plants Used in the Treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Sharma, P.; Gupta, G.K.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Kumar, D. Structure-Activity-Relationship and Mechanistic Insights for Anti-HIV Natural Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, G.M.; Hunter, E. HIV Transmission. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.L.; Kouyos, R.D.; Balmer, B.; Grube, C.; Weber, R.; Günthard, H.F. Frequency and Spectrum of Unexpected Clinical Manifestations of Primary HIV-1 Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 61, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, R.H. Breaking the Asymptomatic Phase of HIV-1 Infection. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 1994, 8, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, S.; Chun, T.-W.; Fauci, A.S. Pathogenic Mechanisms of HIV Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2011, 6, 223–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.W. Pathology of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. J. Korean Med. Sci. 1997, 12, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.; Yebra, M.; Vargas, J.A.; Villarreal, M.; Salas, C. Hemophagocytic syndrome associated with lymphoma in an HIV-infected patient: Presentation of a case and review of the literature. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 1999, 17, 367–368. [Google Scholar]

- Uldrick, T.S.; Little, R.F. How I Treat Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma in Patients Infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Blood 2015, 125, 1226–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnabosco, G.T.; Lopes, L.M.; Andrade, R.L.d.P.; Brunello, M.E.F.; Monroe, A.A.; Villa, T.C.S. Tuberculosis Control in People Living with HIV/AIDS. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2016, 24, e2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, P.H.; Uldrick, T.S.; Yarchoan, R. HIV-Associated Kaposi Sarcoma and Related Diseases. AIDS 2017, 31, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfutwah, A.K.W.; Ngoupo, P.A.T.; Sofeu, C.L.; Ndongo, F.A.; Guemkam, G.; Ndiang, S.T.; Owona, F.; Penda, I.C.; Tchendjou, P.; Rouzioux, C.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in HIV-Infected versus Non-Infected Infants and HIV Disease Progression in Cytomegalovirus Infected versus Non Infected Infants Early Treated with CART in the ANRS 12140-Pediacam Study in Cameroon. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Martínez, N.A.; Mouriño-Pérez, R.R.; Cornejo-Bravo, J.M.; Gaitán-Cepeda, L.A. Factores Relacionados a Candidiasis Oral En Niños y Adolescentes Con VIH, Caracterización de Especies y Susceptibilidad Antifúngica. Rev. Chil. Infectol. 2018, 35, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascort, J.; Aguado, C.; Alastrue, I.; Carrillo, R.; Fransi, L.; Zarco, J. HIV and primary care. Think back to AIDS. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo-Urdiales, A.; Johnson, S.; Smith, R.; Nachega, J.B.; Eshun-Wilson, I. Rapid Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy for People Living with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 6, CD012962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llibre, J.M.; Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca, M.J.; Rivero, A.; Fernández, E. Cuidados Clínicos Del Paciente Con VIH. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2018, 36, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuogi, L.L.; Smith, C.; McFarland, E.J. Retention of HIV-Infected Children in the First 12 Months of Anti-Retroviral Therapy and Predictors of Attrition in Resource Limited Settings: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, A.K.; George, J.M. Antiretroviral Therapy: Current Drugs. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 28, 371–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Osswald, H.L.; Prato, G. Recent Progress in the Development of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV/AIDS. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 5172–5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.C. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection: When to Initiate Therapy, Which Regimen to Use, and How to Monitor Patients on Therapy. Top. Antivir. Med. 2016, 23, 161–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, C.; Malin, J.; Suárez, I.; Fätkenheuer, G. Moderne HIV-Therapie. Internist 2019, 60, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porche, D.J. Saquinavir. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 1996, 7, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Porte, C.J. Saquinavir, the Pioneer Antiretroviral Protease Inhibitor. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2009, 5, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyalrong-Steur, M.; Bogner, J.R.; Seybold, U. Changes in Lipid Profiles after Switching to a Protease Inhibitor-Containing CART—Unfavourable Effect of Fosamprenavir in Obese Patients. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2011, 16, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, M.J.; Hewitt, R.G.; Adams, J.; Della-Coletta, A.; Cox, S.; Morse, G.D. Pharmacokinetics of Ritonavir and Delavirdine in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1694–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kiser, J.J.; Rutstein, R.M.; Samson, P.; Graham, B.; Aldrovandi, G.; Mofenson, L.M.; Smith, E.; Schnittman, S.; Fenton, T.; Brundage, R.C.; et al. Atazanavir and Atazanavir/Ritonavir Pharmacokinetics in HIV-Infected Infants, Children, and Adolescents. AIDS 2011, 25, 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.T.; Kramer, J.H.; Chen, X.; Chmielinska, J.J.; Spurney, C.F.; Weglicki, W.B. Mg Supplementation Attenuates Ritonavir-Induced Hyperlipidemia, Oxidative Stress, and Cardiac Dysfunction in Rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013, 305, R1102–R1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, R.F.; Alli, A.I.; Watters, A.K.; Tsoukas, C.M. Indinavir Crystalluria. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Sanchez, E.M.; Goto, H.; Rivero, D.H.R.F.; Mauad, T.; de Souza, F.N.; Monteiro, A.M.; Gidlund, M. In Vivo Assessment of Antiretroviral Therapy-Associated Side Effects. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tebas, P.; Powderly, W.G. Nelfinavir Mesylate. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2000, 1, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soprano, M.; Sorriento, D.; Rusciano, M.R.; Maione, A.S.; Limite, G.; Forestieri, P.; D’Angelo, D.; D’Alessio, M.; Campiglia, P.; Formisano, P.; et al. Oxidative Stress Mediates the Antiproliferative Effects of Nelfinavir in Breast Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M. Nelfinavir with Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, e561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.; Goa, K.L. Amprenavir. Drugs 2000, 60, 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvieux, C.; Tribut, O. Amprenavir or Fosamprenavir plus Ritonavir in HIV Infection. Drugs 2005, 65, 633–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, T.J.; Midde, N.M.; Rao, P.; Kumar, S. Investigational Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2015, 24, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, O.; Poroikov, V.; Veselovsky, A. Molecular Docking Studies of HIV-1 Resistance to Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors: Mini-Review. Molecules 2018, 23, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachlis, A.R. Zidovudine (Retrovir) Update. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1990, 143, 1177–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Abdelmegeed, M.A.; Jang, S.; Song, B.-J. Zidovudine (AZT) and Hepatic Lipid Accumulation: Implication of Inflammation, Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Mediators. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labhardt, N.D.; Bader, J.; Lejone, T.I.; Ringera, I.; Puga, D.; Glass, T.R.; Klimkait, T. Is Zidovudine First-Line Therapy Virologically Comparable to Tenofovir in Resource-Limited Settings? Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labhardt, N.D.; Müller, U.F.; Ringera, I.; Ehmer, J.; Motlatsi, M.M.; Pfeiffer, K.; Hobbins, M.A.; Muhairwe, J.A.; Muser, J.; Hatz, C. Metabolic Syndrome in Patients on First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy Containing Zidovudine or Tenofovir in Rural Lesotho, Southern Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.A. Update on Didanosine. J. Int. Assoc. Physicians AIDS Care 2002, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.d.V.C.d.; Shimakura, S.E.; Campos, D.P.; Hökerberg, Y.H.M.; Victoriano, F.P.; Ribeiro, S.; Veloso, V.G.; Grinsztejn, B.; Carvalho, M.S. Effects of Antiretroviral Treatment and Nadir CD4 Count in Progression to Cardiovascular Events and Related Comorbidities in a HIV Brazilian Cohort: A Multi-Stage Approach. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devineni, D.; Gallo, J.M. Zalcitabine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1995, 28, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, J.C.; Peters, D.H.; Faulds, D. Zalcitabine. Drugs 1997, 53, 1054–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.; Noble, S. Stavudine. Drugs 1999, 58, 919–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmehrabi, M.; Rohani, S.; Jennings, M.C. Stavudine. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Cryst. Struct. Commun. 2005, 61, o695–o698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, A.G.; Chersich, M.F.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Zuithoff, P.; Moorhouse, M.A.; Lalla-Edward, S.T.; Kambugu, A.; Kumarasamy, N.; Grobbee, D.E.; Barth, R.E.; et al. Lipid Levels, Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Risk over 96 Weeks of Antiretroviral Therapy: A Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Low-Dose Stavudine and Tenofovir. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.N.; Patel, P. Lamivudine for the Treatment of HIV. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, L.J. Dolutegravir/Lamivudine Single-Tablet Regimen: A Review in HIV-1 Infection. Drugs 2020, 80, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, T.A.; Tolstrup, M.; Melchjorsen, J.; Frederiksen, C.A.; Nielsen, U.S.; Langdahl, B.L.; Østergaard, L.; Laursen, A.L. Evaluation of Cardiovascular Biomarkers in HIV-Infected Patients Switching to Abacavir or Tenofovir Based Therapy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzani, M.D.; Resnati, C.; Di Cristo, V.; Riva, A.; Gervasoni, C. Abacavir-Induced Liver Toxicity. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 20, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jesson, J.; Dahourou, D.L.; Renaud, F.; Penazzato, M.; Leroy, V. Adverse Events Associated with Abacavir Use in HIV-Infected Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet HIV 2016, 3, e64–e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, M.; Torres, R.; Jusdado, J.J.; Pastor, S.; Agud, J.L. Predictive factors of clinically significant drug-drug interactions among regimens based on protease inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and raltegravir. Med. Clin. 2016, 146, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombier, M.-A.; Molina, J.-M. Doravirine: A Review. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2018, 13, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.; Mast, N.; Pikuleva, I.A. Drugs and Scaffold That Inhibit Cytochrome P450 27A1 In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Pharmacol. 2018, 93, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhmanina, N.Y.; van den Anker, J.N. Efavirenz in the Therapy of HIV Infection. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, H.; Cruz, J.P.; Aniceto, N.; Ribeiro, A.C.; Fernandes, A.; Paixão, P.; Antunes, F.; Morais, J. Population Approach to Efavirenz Therapy. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 3161–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwag, T.; Meng, Z.; Sui, Y.; Helsley, R.N.; Park, S.-H.; Wang, S.; Greenberg, R.N.; Zhou, C. Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor Efavirenz Activates PXR to Induce Hypercholesterolemia and Hepatic Steatosis. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, V.E.; Sánchez-Parra, C.; Villar, S.S. Interacciones Medicamentosas de Etravirina, Etravirine Drug Interactions Etravirina. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clín. 2009, 27 (Suppl. S2), 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portilla, J. Seguridad y Tolerabilidad de Etravirina, Safety and Tolerability of Etravirine. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clín. 2009, 27 (Suppl. S2), 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszewska, A.; Nowak, B.; Niżański, W.; Eberhardt, M.; Domrazek, K.; Nikodem, A.; Wiatrak, B.; Zduniak, K.; Olejnik, K.; Merwid-Ląd, A.; et al. Long-Term Administration of Abacavir and Etravirine Impairs Semen Quality and Alters Redox System and Bone Metabolism in Growing Male Wistar Rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 5596090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirochnick, M.; Clarke, D.F.; Dorenbaum, A. Nevirapine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2000, 39, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumero, E.; Podzamczer, D. The Role of Nevirapine in the Treatment of HIV-1 Disease. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2001, 2, 2065–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpadi, S.; Shiau, S.; Strehlau, R.; Martens, L.; Patel, F.; Coovadia, A.; Abrams, E.J.; Kuhn, L. Metabolic Abnormalities and Body Composition of HIV-Infected Children on Lopinavir or Nevirapine-Based Antiretroviral Therapy. Arch. Dis. Child. 2013, 98, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, P.; Di Biagio, A.; Rusconi, S.; Cicalini, S.; D’Abbraccio, M.; d’Ettorre, G.; Martinelli, C.; Nunnari, G.; Sighinolfi, L.; Spagnuolo, V.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk and Dyslipidemia among Persons Living with HIV: A Review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkin, C.; Arasteh, K.; Górgolas Hernández-Mora, M.; Pokrovsky, V.; Overton, E.T.; Girard, P.-M.; Oka, S.; Walmsley, S.; Bettacchi, C.; Brinson, C.; et al. Long-Acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine after Oral Induction for HIV-1 Infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duracinsky, M.; Leclercq, P.; Armstrong, A.R.; Dolivo, M.; Mouly, F.; Chassany, O. A Longitudinal Evaluation of the Impact of a Polylactic Acid Injection Therapy on Health Related Quality of Life amongst HIV Patients Treated with Anti-Retroviral Agents under Real Conditions of Use. BMC Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bednasz, C.; Luque, A.E.; Zingman, B.S.; Fischl, M.A.; Gripshover, B.M.; Venuto, C.S.; Gu, J.; Feng, Z.; DiFrancesco, R.; Morse, G.D.; et al. Lipid-Lowering Therapy in HIV-Infected Patients: Relationship with Antiretroviral Agents and Impact of Substance-Related Disorders. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2016, 14, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bakari, A.G.; Sani-Bello, F.; Shehu, M.S.; Mai, A.; Aliyu, I.S.; Lawal, I.I. Anti-Retroviral Therapy Induced Diabetes in a Nigerian. Afr. Health Sci. 2007, 7, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luetkemeyer, A.F.; Havlir, D.V.; Currier, J.S. Complications of HIV Disease and Antiretroviral Treatment. Top. HIV Med. Publ. Int. AIDS Soc. USA 2010, 18, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Katsiki, N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Mantzoros, C.S. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Dyslipidemia: An Update. Metab. Clin. Exp. 2016, 65, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabarpour, M.; Rashtchizadeh, N.; Argani, H.; Ghorbanihaghjo, A.; Ranjbarzadhag, M.; Sanajou, D.; Panah, F.; Alirezaei, A. The Impact of Dyslipidemia and Oxidative Stress on Vasoactive Mediators in Patients with Renal Dysfunction. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2019, 51, 2235–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, L.L.; Srivastava, R.; Schoeb, T.R.; Moore, R.D.; Barnes, S.; Kabarowski, J.H. Cholesterol-Independent Suppression of Lymphocyte Activation, Autoimmunity, and Glomerulonephritis by Apolipoprotein A-I in Normocholesterolemic Lupus-Prone Mice. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4685–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelesidis, T.; Jackson, N.; McComsey, G.A.; Wang, X.; Elashoff, D.; Dube, M.P.; Brown, T.T.; Yang, O.O.; Stein, J.H.; Currier, J.S. Oxidized Lipoproteins Are Associated with Markers of Inflammation and Immune Activation in HIV-1 Infection. AIDS 2016, 30, 2625–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funderburg, N.T.; Mehta, N.N. Lipid Abnormalities and Inflammation in HIV Inflection. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016, 13, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprez, D.A.; Kuller, L.H.; Tracy, R.; Otvos, J.; Cooper, D.A.; Hoy, J.; Neuhaus, J.; Paton, N.I.; Friis-Moller, N.; Lampe, F.; et al. Lipoprotein Particle Subclasses, Cardiovascular Disease and HIV Infection. Atherosclerosis 2009, 207, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, I.; Garg, A. Lipodystrophy Syndromes. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 45, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brayson, D.; Frustaci, A.; Verardo, R.; Chimenti, C.; Russo, M.A.; Hayward, R.; Ahmad, S.; Vizcay-Barrena, G.; Protti, A.; Zammit, P.S.; et al. Prelamin A Mediates Myocardial Inflammation in Dilated and HIV-Associated Cardiomyopathies. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e126315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.; Hall, P.A.; Chinnery, P.F.; Payne, B.A.I. HIV Treatment and Associated Mitochondrial Pathology: Review of 25 Years of in Vitro, Animal, and Human Studies. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014, 42, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddler, S.A.; Smit, E.; Cole, S.R.; Li, R.; Chmiel, J.S.; Dobs, A.; Palella, F.; Visscher, B.; Evans, R.; Kingsley, L.A. Impact of HIV Infection and HAART on Serum Lipids in Men. JAMA 2003, 289, 2978–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, E.R.; McAuley, N.; O’Halloran, J.A.; Rock, C.; Low, J.; Satchell, C.S.; Lambert, J.S.; Sheehan, G.J.; Mallon, P.W.G. The Expression of Cholesterol Metabolism Genes in Monocytes from HIV-Infected Subjects Suggests Intracellular Cholesterol Accumulation. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 207, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Liu, L.; Wei, D.; Lv, Y.; Wang, G.; Xiong, W.; Wang, X.; Altaf, A.; Wang, L.; He, D.; et al. P2X7R Is Involved in the Progression of Atherosclerosis by Promoting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015, 35, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J. Research Progress on the Relationship between the NLRP3 Inflammasome and Immune Reconstitution in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving Antiretroviral Therapy. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 3179200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivero, E.T.; Guo, M.-L.; Periyasamy, P.; Liao, K.; Callen, S.E.; Buch, S. HIV-1 Tat Primes and Activates Microglial NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation. J. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 3599–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, J.-W.; Huang, H.-H.; Fan, X.; Huang, L.; Deng, J.-N.; Tu, B.; Wang, K.; Li, J.; Zhou, M.-J.; et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome Induces CD4+ T Cell Loss in Chronically HIV-1-Infected Patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e138861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Pitzer, A.L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, P.-L. Coronary Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Nucleotide Oligomerization Domain-like Receptor Protein with Pyrin Domain Containing 3 Inflammasome Activation during Hypercholesterolemia: Beyond Inflammation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 1084–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, K.C.; Rader, D.J. Nuclear Receptors and MicroRNA-144 Coordinately Regulate Cholesterol Efflux. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 1529–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujawar, Z.; Rose, H.; Morrow, M.P.; Pushkarsky, T.; Dubrovsky, L.; Mukhamedova, N.; Fu, Y.; Dart, A.; Orenstein, J.M.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Impairs Reverse Cholesterol Transport from Macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopeyin, A.; Zhou, L.; Li, M.; Barakat, L.; Paintsil, E. Dysregulation of Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 2 Gene in HIV Treatment-Experienced Individuals. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Aliyari, R.; Chikere, K.; Li, G.; Marsden, M.D.; Smith, J.K.; Pernet, O.; Guo, H.; Nusbaum, R.; Zack, J.A.; et al. Interferon-Inducible Cholesterol-25-Hydroxylase Broadly Inhibits Viral Entry by Production of 25-Hydroxycholesterol. Immunity 2013, 38, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saulle, I.; Ibba, S.V.; Vittori, C.; Fenizia, C.; Mercurio, V.; Vichi, F.; Caputo, S.L.; Trabattoni, D.; Clerici, M.; Biasin, M. Sterol Metabolism Modulates Susceptibility to HIV-1 Infection. AIDS 2020, 34, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echeverria, P.; Guardiola, M.; González, M.; Vallvé, J.C.; Bonjoch, A.; Puig, J.; Clotet, B.; Ribalta, J.; Negredo, E. Association between Polymorphisms in Genes Involved in Lipid Metabolism and Immunological Status in Chronically HIV-Infected Patients. Antivir. Res. 2015, 114, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obirikorang, C.; Acheampong, E.; Quaye, L.; Yorke, J.; Amos-Abanyie, E.K.; Akyaw, P.A.; Anto, E.O.; Bani, S.B.; Asamoah, E.A.; Batu, E.N. Association of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Dyslipidemia in Antiretroviral Exposed HIV Patients in a Ghanaian Population: A Case-Control Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliari, C.F.d.S.; de Oliveira, C.N.; Vogel, G.M.; da Silva, P.B.; Linden, R.; Lazzaretti, R.K.; Notti, R.K.; Sprinz, E.; Mattevi, V.S. Investigation of SIRT1 Gene Variants in HIV-Associated Lipodystrophy and Metabolic Syndrome. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2020, 43, e20190142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.S.; Carvalho, T.L.; do Ó, K.P.; da Nóbrega, D.N.; dos Santos Souza, R.; da Silva Lima, V.F.; Farias, I.C.C.; de Mendonça Belmont, T.F.; de Mendonça Cavalcanti, M.d.S.; de Barros Miranda-Filho, D. Association of the Polymorphisms of the Genes APOC3 (Rs2854116), ESR2 (Rs3020450), HFE (Rs1799945), MMP1 (Rs1799750) and PPARG (Rs1801282) with Lipodystrophy in People Living with HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy: A Systematic Review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 4779–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renga, B.; Francisci, D.; Carino, A.; Marchianò, S.; Cipriani, S.; Chiara Monti, M.; Del Sordo, R.; Schiaroli, E.; Distrutti, E.; Baldelli, F.; et al. The HIV Matrix Protein P17 Induces Hepatic Lipid Accumulation via Modulation of Nuclear Receptor Transcriptoma. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 15403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoo, S.M.; Chuturgoon, A.A.; Singh, B.; Nagiah, S. Hepatic Expression of Cholesterol Regulating Genes Favour Increased Circulating Low-Density Lipoprotein in HIV Infected Patients with Gallstone Disease: A Preliminary Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sviridov, D.; Mukhamedova, N.; Makarov, A.A.; Adzhubei, A.; Bukrinsky, M. Comorbidities of HIV Infection: Role of Nef-Induced Impairment of Cholesterol Metabolism and Lipid Raft Functionality. AIDS 2020, 34, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastav, S.; Kino, T.; Cunningham, T.; Ichijo, T.; Schubert, U.; Heinklein, P.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kopp, J.B. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-1 Viral Protein R Suppresses Transcriptional Activity of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor {gamma} and Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation: Implications for HIV-Associated Lipodystrophy. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, S.; Mulet, C.T.; Atluri, V.S.R.; Agudelo, M.; Rosenberg, R.; Devieux, J.G.; Nair, M.P.N. Oxidative Stress in HIV Infection and Alcohol Use: Role of Redox Signals in Modulation of Lipid Rafts and ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arauz, J.; Ramos-Tovar, E.; Muriel, P. Redox State and Methods to Evaluate Oxidative Stress in Liver Damage: From Bench to Bedside. Ann. Hepatol. 2016, 15, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K.J.A. Mitochondrial Free Radical Generation, Oxidative Stress, and Aging11This Article Is Dedicated to the Memory of Our Dear Friend, Colleague, and Mentor Lars Ernster (1920–1998), in Gratitude for All He Gave to Us. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Holbrook, N.J. Oxidants, Oxidative Stress and the Biology of Ageing. Nature 2000, 408, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dröge, W. Free Radicals in the Physiological Control of Cell Function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darley-Usmar, V.; Halliwell, B. Blood Radicals: Reactive Nitrogen Species, Reactive Oxygen Species, Transition Metal Ions, and the Vascular System. Pharm. Res. 1996, 13, 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feillet-Coudray, C.; Fouret, G.; Vigor, C.; Bonafos, B.; Jover, B.; Blachnio-Zabielska, A.; Rieusset, J.; Casas, F.; Gaillet, S.; Landrier, J.F.; et al. Long-Term Measures of Dyslipidemia, Inflammation, and Oxidative Stress in Rats Fed a High-Fat/High-Fructose Diet. Lipids 2019, 54, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaunig, E.J. Oxidative Stress and Cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24, 4771–4778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative Stress and Advanced Lipoxidation and Glycation End Products (ALEs and AGEs) in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3085756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandas, A.; Iorio, E.L.; Congiu, M.G.; Balestrieri, C.; Mereu, A.; Cau, D.; Dessì, S.; Curreli, N. Oxidative Imbalance in HIV-1 Infected Patients Treated with Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2009, 2009, 749575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; West, N.E.J.; Black, E.; McDonald, D.; Ratnatunga, C.; Pillai, R.; Channon, K.M. Vascular Superoxide Production by NAD(P)H Oxidase. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, e85–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, K.Y.; Russell, J.M.; Jennings, M.H.; Alexander, J.S.; Granger, D.N. Platelet-Associated NAD(P)H Oxidase Contributes to the Thrombogenic Phenotype Induced by Hypercholesterolemia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, C.A.; La Favor, J.D.; Kim, D.-H.; Hickner, R.C. Endothelial Dysfunction: Is There a Hyperglycemia-Induced Imbalance of NOX and NOS? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbim, C.; Pillet, S.; Prevost, M.H.; Preira, A.; Girard, P.M.; Rogine, N.; Matusani, H.; Hakim, J.; Israel, N.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A. Redox and Activation Status of Monocytes from Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Patients: Relationship with Viral Load. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 4561–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronaldson, P.T.; Bendayan, R. HIV-1 Viral Envelope Glycoprotein Gp120 Produces Oxidative Stress and Regulates the Functional Expression of Multidrug Resistance Protein-1 (Mrp1) in Glial Cells. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1298–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, L.; Calosing, C.; Sun, B.; Grunfeld, C.; Rempel, H. Monocyte Activation from Interferon-α in HIV Infection Increases Acetylated LDL Uptake and ROS Production. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; Wei, F.; Liu, D.; Liu, K.; Chen, D. Accumulation of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Damage in the Frontal Cortex Cells of Patients with HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders. Brain Res. 2012, 1458, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Amine, R.; Germini, D.; Zakharova, V.V.; Tsfasman, T.; Sheval, E.V.; Louzada, R.A.N.; Dupuy, C.; Bilhou-Nabera, C.; Hamade, A.; Najjar, F.; et al. HIV-1 Tat Protein Induces DNA Damage in Human Peripheral Blood B-Lymphocytes via Mitochondrial ROS Production. Redox Biol. 2018, 15, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanchu, A.; Rana, S.V.; Pallikkuth, S.; Sachdeva, R.K. Short Communication: Oxidative Stress in HIV-Infected Individuals: A Cross-Sectional Study. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2009, 25, 1307–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, Y.; Yoshikawa, T. Antioxidants as anti-ageing medicine. Nihon Rinsho Jpn. J. Clin. Med. 2009, 67, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, R.G.; Lunkenbein, S.; Ströhle, A.; Hahn, A. Antioxidants in Food: Mere Myth or Magic Medicine? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2012, 52, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candas, D.; Li, J.J. MnSOD in Oxidative Stress Response-Potential Regulation via Mitochondrial Protein Influx. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1599–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, J.S.; Doucette, P.A.; Zittin Potter, S. Copper-Zinc Superoxide Dismutase and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005, 74, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Reszka, K.J.; Fukai, T.; Weintraub, N.L. Extracellular Superoxide Dismutase (EcSOD) in Vascular Biology: An Update on Exogenous Gene Transfer and Endogenous Regulators of EcSOD. Transl. Res. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 2008, 151, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.R.; Gao, Y.; DeLeon, E.R.; Arif, M.; Arif, F.; Arora, N.; Straub, K.D. Catalase as a Sulfide-Sulfur Oxido-Reductase: An Ancient (and Modern?) Regulator of Reactive Sulfur Species (RSS). Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanschmann, E.-M.; Godoy, J.R.; Berndt, C.; Hudemann, C.; Lillig, C.H. Thioredoxins, Glutaredoxins, and Peroxiredoxins—Molecular Mechanisms and Health Significance: From Cofactors to Antioxidants to Redox Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 1539–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. A Review on Antioxidants, Prooxidants and Related Controversy: Natural and Synthetic Compounds, Screening and Analysis Methodologies and Future Perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; He, T.; Farrar, S.; Ji, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, X. Antioxidants Maintain Cellular Redox Homeostasis by Elimination of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 532–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambon, P. A Decade of Molecular Biology of Retinoic Acid Receptors. FASEB J. 1996, 10, 940–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Tanoury, Z.; Piskunov, A.; Rochette-Egly, C. Vitamin A and Retinoid Signaling: Genomic and Nongenomic Effects: Thematic Review Series: Fat-Soluble Vitamins: Vitamin A. J. Lipid Res. 2013, 54, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.-C.; Yeh, W.-C.; Ohashi, P.S. LPS/TLR4 Signal Transduction Pathway. Cytokine 2008, 42, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, L.P.; Ross, A.C.; Stephensen, C.B.; Bohn, T.; Tanumihardjo, S.A. Metabolic Effects of Inflammation on Vitamin A and Carotenoids in Humans and Animal Models. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Xiu, P.; Li, F.; Xin, C.; Li, K. Vitamin A Supplementation Alleviates Extrahepatic Cholestasis Liver Injury through Nrf2 Activation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 273692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Bartuzi, P.; Heegsma, J.; Dekker, D.; Kloosterhuis, N.; de Bruin, A.; Jonker, J.W.; van de Sluis, B.; Faber, K.N. Impaired Hepatic Vitamin A Metabolism in NAFLD Mice Leading to Vitamin A Accumulation in Hepatocytes. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 309–325.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as Natural Functional Pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Carotenoids and Human Health. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapiero, H.; Townsend, D.M.; Tew, K.D. The Role of Carotenoids in the Prevention of Human Pathologies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2004, 58, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, A.J.; Lowe, G.M. Antioxidant and Prooxidant Properties of Carotenoids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001, 385, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedor, J.; Burda, K. Potential Role of Carotenoids as Antioxidants in Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2014, 6, 466–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, R.C.; Ademosun, O.T.; Ajanaku, C.O.; Olanrewaju, I.O.; Walton, J.C. Free Radical Mediated Oxidative Degradation of Carotenes and Xanthophylls. Molecules 2020, 25, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucci, M.; Di Tomo, P.; Tritschler, F.; Cordone, V.G.P.; Lanuti, P.; Bologna, G.; Di Silvestre, S.; Di Pietro, N.; Pipino, C.; Mandatori, D.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Role of Carotenoids in Endothelial Cells Derived from Umbilical Cord of Women Affected by Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 8184656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.-A.; Hayden, M.M.; Bannerman, S.; Jansen, J.; Crowe-White, K.M. Anti-Apoptotic Effects of Carotenoids in Neurodegeneration. Molecules 2020, 25, 3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, A.; Basirnejad, M.; Shahbazi, S.; Bolhassani, A. Carotenoids: Biochemistry, Pharmacology and Treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1290–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An Overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S.L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules 2020, 25, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciumărnean, L.; Milaciu, M.V.; Runcan, O.; Vesa Ștefan, C.; Răchișan, A.L.; Negrean, V.; Perné, M.-G.; Donca, V.I.; Alexescu, T.-G.; Para, I.; et al. The Effects of Flavonoids in Cardiovascular Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, S.; Poh, C.L. Flavonoids as Antiviral Agents for Enterovirus A71 (EV-A71). Viruses 2020, 12, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.; Moccia, S.; Spagnuolo, C.; Tedesco, I.; Russo, G.L. Roles of Flavonoids against Coronavirus Infection. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2020, 328, 109211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badshah, S.L.; Faisal, S.; Muhammad, A.; Poulson, B.G.; Emwas, A.H.; Jaremko, M. Antiviral Activities of Flavonoids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 140, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djedjibegovic, J.; Marjanovic, A.; Panieri, E.; Saso, L. Ellagic Acid-Derived Urolithins as Modulators of Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5194508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evtyugin, D.D.; Magina, S.; Evtuguin, D.V. Recent Advances in the Production and Applications of Ellagic Acid and Its Derivatives. A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kábelová, A.; Malínská, H.; Marková, I.; Oliyarnyk, O.; Chylíková, B.; Šeda, O. Ellagic Acid Affects Metabolic and Transcriptomic Profiles and Attenuates Features of Metabolic Syndrome in Adult Male Rats. Nutrients 2021, 13, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nankar, R.P.; Doble, M. Hybrid Drug Combination: Anti-Diabetic Treatment of Type 2 Diabetic Wistar Rats with Combination of Ellagic Acid and Pioglitazone. Phytomedicine 2017, 37, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenSaad, L.A.; Kim, K.H.; Quah, C.C.; Kim, W.R.; Shahimi, M. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Ellagic Acid, Gallic Acid and Punicalagin A&B Isolated from Punica Granatum. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, K.; Chen, M.; Wang, M.; Jia, Y.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, A. Dietary Ellagic Acid Improves Oxidant-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis: Role of Nrf2 Activation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 175, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkban, T.; Boonprom, P.; Bunbupha, S.; Welbat, J.U.; Kukongviriyapan, U.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Pakdeechote, P.; Prachaney, P. Ellagic Acid Prevents L-NAME-Induced Hypertension via Restoration of ENOS and P47phox Expression in Rats. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5265–5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, J.B.R.; Porto, H.K.P.; Lopes, F.M.; Batista, A.C.; Rocha, M.L. Protective Effects of Ellagic Acid on Cardiovascular Injuries Caused by Hypertension in Rats. Planta Med. 2017, 83, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Nagaoka, S. Ellagic Acid Affects MRNA Expression Levels of Genes That Regulate Cholesterol Metabolism in HepG2 Cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, V.; Manente, L.; Viglietti, R.; Parrella, G.; Parrella, R.; Gargiulo, M.; Sangiovanni, V.; Perna, A.; Baldi, A.; De Luca, A.; et al. Comparative Transcriptional Profiling in HIV-Infected Patients Using Human Stress Arrays: Clues to Metabolic Syndrome. Vivo 2012, 26, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- van Wijk, J.P.H.; Cabezas, M.C. Hypertriglyceridemia, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Disease in HIV-Infected Patients: Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy and Adipose Tissue Distribution. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2012, 2012, 201027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- ElZohary, L.; Weglicki, W.B.; Chmielinska, J.J.; Kramer, J.H.; Mak, I.T. Mg-Supplementation Attenuated Lipogenic and Oxidative/Nitrosative Gene Expression Caused by Combination Antiretroviral Therapy (CART) in HIV-1-Transgenic Rats. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israël, N.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; Aillet, F.; Virelizier, J.L. Redox Status of Cells Influences Constitutive or Induced NF-Kappa B Translocation and HIV Long Terminal Repeat Activity in Human T and Monocytic Cell Lines. J. Immunol. 1992, 149, 3386. [Google Scholar]

- Dezube, B.J.; Pardee, A.B.; Chapman, B.; Beckett, L.A.; Korvick, J.A.; Novick, W.J.; Chiurco, J.; Kasdan, P.; Ahlers, C.M.; Ecto, L.T. Pentoxifylline Decreases Tumor Necrosis Factor Expression and Serum Triglycerides in People with AIDS. NIAID AIDS Clinical Trials Group. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 1993, 6, 787–794. [Google Scholar]

- Munis, J.R.; Richman, D.D.; Kornbluth, R.S. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Infection of Macrophages in Vitro Neither Induces Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)/Cachectin Gene Expression nor Alters TNF/Cachectin Induction by Lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Investig. 1990, 85, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadeja, R.N.; Upadhyay, K.K.; Devkar, R.V.; Khurana, S. Naturally Occurring Nrf2 Activators: Potential in Treatment of Liver Injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3453926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.E.M.; Bakr, A.G.; Abo-youssef, A.M.; Azouz, A.A.; Hemeida, R.A.M. Targeting Keap-1/Nrf-2 Pathway and Cytoglobin as a Potential Protective Mechanism of Diosmin and Pentoxifylline against Cholestatic Liver Cirrhosis. Life Sci. 2018, 207, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Hou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, B.; Fu, J.; Zheng, H.; Yarborough, K.; Woods, C.G.; Liu, D.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Adipose Deficiency of Nrf2 in Ob/Ob Mice Results in Severe Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes 2013, 62, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-S.; Li, H.-Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, M.-R.; Zhou, H.-S. Nrf2 Is Involved in Inhibiting Tat-Induced HIV-1 Long Terminal Repeat Transactivation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2009, 47, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-S.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wu, T.-C.; Zhang, F.-J. Tanshinone II A Inhibits Tat-Induced HIV-1 Transactivation Through Redox-Regulated AMPK/Nampt Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2014, 229, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Liao, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, X.; Hai, C. Oleanolic Acid Improves Hepatic Insulin Resistance via Antioxidant, Hypolipidemic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 376, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Donepudi, A.C.; More, V.R.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Li, L.; Guo, L.; Yan, B.; Chatterjee, T.; Weintraub, N.; Slitt, A.L. Deficiency in Nrf2 Transcription Factor Decreases Adipose Tissue Mass and Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in Leptin-Deficient Mice. Obesity 2015, 23, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozaykut, P.; Karademir, B.; Yazgan, B.; Sozen, E.; Siow, R.C.M.; Mann, G.E.; Ozer, N.K. Effects of Vitamin E on Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ and Nuclear Factor-Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 in Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Atherosclerosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 70, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakkiyalakshmi, E.; Sireesh, D.; Sakthivadivel, M.; Sivasubramanian, S.; Gunasekaran, P.; Ramkumar, K.M. Anti-Hyperlipidemic and Anti-Peroxidative Role of Pterostilbene via Nrf2 Signaling in Experimental Diabetes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 777, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani, S.B.; Danquah, K.O.; Obirikorang, C.; Owiredu, W.K.B.A.; Quaye, L.; Muonir Der, E.; Acheampong, E.; Adams, Y.; Dapare, P.P.M.; Banyeh, M.; et al. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in LCAT May Contribute to Dyslipidaemia in HIV-Infected Individuals on HAART in a Ghanaian Population. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farràs, M.; Castañer, O.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Hernáez, Á.; Schröder, H.; Subirana, I.; Muñoz-Aguayo, D.; Gaixas, S.; de la Torre, R.; Farré, M.; et al. Complementary Phenol-Enriched Olive Oil Improves HDL Characteristics in Hypercholesterolemic Subjects. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover, Controlled Trial. The VOHF Study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1758–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, C.; Ding, X.-Q.; Pan, Y.; Gu, T.-T.; Wang, M.-X.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, F.-M.; Wang, S.-J.; Kong, L.-D. Quercetin and Allopurinol Reduce Liver Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein to Alleviate Inflammation and Lipid Accumulation in Diabetic Rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 169, 1352–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-Y.; Pan, Y.; Wang, R.; Kang, L.-L.; Xue, Q.-C.; Wang, X.-N.; Kong, L.-D. Quercetin Inhibits AMPK/TXNIP Activation and Reduces Inflammatory Lesions to Improve Insulin Signaling Defect in the Hypothalamus of High Fructose-Fed Rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quagliariello, V.; Armenia, E.; Aurilio, C.; Rosso, F.; Clemente, O.; de Sena, G.; Barbarisi, M.; Barbarisi, A. New Treatment of Medullary and Papillary Human Thyroid Cancer: Biological Effects of Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Loaded with Quercetin Alone or in Combination to an Inhibitor of Aurora Kinase. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, J.M.; Furtado, M.N.; de Morais Nunes, E.R.; Sucupira, M.C.A.; Diaz, R.S.; Janini, L.M.R. Modulation of Epigenetic Factors during the Early Stages of HIV-1 Infection in CD4+ T Cells in Vitro. Virology 2018, 523, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, J.; Lagman, M.; Saing, T.; Singh, M.K.; Tudela, E.V.; Morris, D.; Anderson, J.; Daliva, J.; Ochoa, C.; Patel, N.; et al. Liposomal Glutathione Supplementation Restores TH1 Cytokine Response to Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Infection in HIV-Infected Individuals. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2015, 35, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quagliariello, V.; Masarone, M.; Armenia, E.; Giudice, A.; Barbarisi, M.; Caraglia, M.; Barbarisi, A.; Persico, M. Chitosan-Coated Liposomes Loaded with Butyric Acid Demonstrate Anticancer and Anti-Inflammatory Activity in Human Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ART | Pediatric Dose | Adult Dose | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saquinavir (SQV, Invirase) | 350 mg/12 h | 600 mg/8 h | Choice as antiretroviral in pregnancy and minimally secreted in breast milk. Efficient hepatic secretion (88%). | Gastrointestinal intolerance, headache, increased transaminases. The safety and activity of saquinavir combined with ritonavir in pediatric patients under two years of age are not established. Risk of arrhythmias and hypertension.Chronic consumption increased plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels | [37,38,39] |

| Ritonavir (Norvir) | >two years 400 mg/100 mg/12 h | 600 mg/12 h | Better absorption in lymphoid tissue can be taken together with food and generates an improved treatment tolerance. | Long-term gastrointestinal problems, pancreatitis, paresthesias, increased transaminases, asthenia, hepatitis, and palate alteration. Alteration of genes expression related lipid metabolism (CYP7A1, CITED2 and G6PC) | [40,41,42] |

| Indinavir (Crixivan) | >three years 500 mg/m2/8 h | 800 mg + ritonavir 100 mg/12 h. | Bioavailability of 60%. Used in association with other antiretrovirals to delay disease progression and reduce the risk of opportunistic infections. | Decreases gastric pH, short half-life (3 administrations per day), presenting dietary restrictions (fasting or bland food). Development of nephrolithiasis, so abundant liquid consumption is essential. Increased plasma cholesterol, glucose, and triglyceride levels | [43,44] |

| Nelfinavir (Viracept) | 45–55 mg/kg/12 h 25–35 mg/kg/8 h | 750 mg/8 h | The antiviral effect is prolonged for at least 21 months. Bioavailability increases when combined with food. | Conditions including skin rash, allergic reactions, hepatitis, abnormalities in liver function tests, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, fatigue, fever, headache, and myalgia may appear. Long-term use can produce Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. It readily crosses the placental barrier, and its presence in breast milk has been reported. Related with apoptosis and necrosis by increasing ROS production | [45,46,47] |

| Amprenavir (Lexiva) | 20 mg/kg dos veces al día o 15 mg/kg 3 veces al día | 1200 mg/12 h | Improved dosing schedule for twice-daily administration with no restrictions on meal times or fluids. Absorption is increased after oral administration. The bioavailability of the solution is 86% compared to caplet formulation. | Owing to its formulation, vitamin E supplementation is avoided. It is not recommended for people with renal or hepatic insufficiency. Changes in the lipid profile by developing hypertriglyceridemia or hypercholesterolemia. | [48,49] |

| ART | Pediatric Dose | Adult Dose | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zidovudine (Retrovir) | Infants 4–9 kg: 12 mg/kg/12 h Infants 9–30 kg: 9 mg/kg/12 h | 300 mg/12 h | Combined with IFN-α prevents toxic side effects. Safety during pregnancy For use as first-line prophylaxis of infection in newborn infants. | Produces lactic acidosis usually associated with hepatomegaly and hepatic steatosis. Treatment with zidovudine is associated with the appearance of lipoatrophy. Long-term consumption can lead to osteonecrosis, anemia, and neutropenia.Elevated oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress resulting in lipid acummulation | [52,53,54,55] |

| Didanosine (Videx) | >90 days age: 120 mg/m2/12 h >6 years 240 mg/m2 | >60 kg 200 mg/12 h <60 kg 125 mg/12 h | Replacement for people intolerant to zidovudine | Combined with stavudine leads to lactic acidosis, pancreatitis, lipoatrophy, and hepatic dysfunction. | [56,57] |

| Zalcitabine (Hivid) | >4 years 500 mg/m2/8 h | Combinated 800 mg + 100 mg ritonavir/12 h | Stable at gastric pH and shows reliable bioavailability (approximately 70% to 90%). It is considered ten times more potent than zidovudine (AZT) on a molar basis in vitro. | Associated with the development of peripheral neuropathy, the incidence of anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, and elevated glutamic-oxaloacetic and glutamic-pyruvic transaminases. | [58,59] |

| Stavudine (Zerit) | <30 kg 1 mg/kg twice daily | <60 kg 30 mg twice daily >60 kg 40 mg twice daily | Powder presentation for pediatric patients under three months of age and adults with swallowing problems and dysphagia. | Medium- and long-term administration produces lactic acidosis, lipoatrophy, and polyneuropathy. Increased total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides | [60,61,62] |

| Lamivudine (Epivir) | 150 mg/ 12 h | 300 mg/24 h | The oral suspension enhances the drug administration for children over three months of age and weighing less than 14 kg or for patients with dysphagia. Absolute bioavailability is close to 82% and 68% in adults and children. Potent antiviral activity against chronic hepatitis B and HIV | It is not recommended as monotherapy.Administration of this antiretroviral can lead to pancreatitis, hepatitis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, and alopecia. Combined short-term decreased HDL-C and increased total cholesterol | [63,64] |

| Abacavir (Ziagen) | ≥3 months 8 mg/kg/12 h | 300 mg/12 h 600 mg/24 h | Dosage is once a day. Very low toxicity | It is contraindicated in patients with end-stage renal disease and not recommended in pregnant women. Produces lactic acidosis. Increased total cholesterol at short-term. | [65,66,67] |

| ART | Pediatric Dose | Adult Dose | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delavirdine (Rescriptor) | 10–47 kg 15 mg/kg/day | 800 mg/24 h | Administer without food restriction. No interaction with proton pump inhibitors. No inhibition and non-induction of CYP450 and CYP34. One-time daily administration is allowed. | Consumption of this product could result in headaches, hypophosphatemia, hypomagnesemia, hypertension, dyspnea, and aminotransferase elevation. It is not suitable for use during pregnancy. Increased plasma cholesterol levels by CYP27A1 inhibition | [69,70] |

| Efavirenz (Sustiva) | >10 kg 200 mg/24 h | >40 kg 600 mg/24 h | Dosage is once a day | It is not administered under three months of age and as monotherapy mainly for its adverse reactions involving the nervous system. Increased cholesterol through activation of PXR and overexpression of lipogenic genes. | [71,72,73] |

| Etravirine (Intelence) | 16–20 kg 100 mg/12 h. >25 kg 125 mg/12 h | 200 mg/12 h | Dissolves in water for easy administration. Suitable for use during pregnancy. | Long-term consumption of this medication causes osteonecrosis, rash, diarrhea, and nausea. Changes in redox system modifying catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase activity. | [74,75,76] |

| Nevirapine (Viramune) | >8 years 120 mg/12 h | 200 mg/12 h | Bioavailability of 90%. Efficient in the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. | Long-term administration can cause skin rash and hepatic toxicity. Not used during lactation. Combined with another ART decreased HDL-C and increased LDL-C, total cholesterol, and triglycerides | [77,78,79] |

| Rilpivirine (Edurant) | <8 years 200 mg/m224 h | 400 mg/24 h | Suitable for use during pregnancy | Long-term administration produces severe skin rash and lipodystrophy. Less effective in lipid profile regulation compared to other NRTIs | [64,80,81] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Osorio, A.S.; Jaen-Vega, S.; Fernández-Martínez, E.; Ortíz-Rodríguez, M.A.; Martínez-Salazar, M.F.; Jiménez-Sánchez, R.C.; Flores-Chávez, O.R.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Arias-Rico, J.; Arteaga-García, F.; et al. Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Dysregulation of Gene Expression and Lipid Metabolism in HIV+ Patients: Beneficial Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105592

Jiménez-Osorio AS, Jaen-Vega S, Fernández-Martínez E, Ortíz-Rodríguez MA, Martínez-Salazar MF, Jiménez-Sánchez RC, Flores-Chávez OR, Ramírez-Moreno E, Arias-Rico J, Arteaga-García F, et al. Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Dysregulation of Gene Expression and Lipid Metabolism in HIV+ Patients: Beneficial Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(10):5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105592

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Osorio, Angélica Saraí, Sinaí Jaen-Vega, Eduardo Fernández-Martínez, María Araceli Ortíz-Rodríguez, María Fernanda Martínez-Salazar, Reyna Cristina Jiménez-Sánchez, Olga Rocío Flores-Chávez, Esther Ramírez-Moreno, José Arias-Rico, Felipe Arteaga-García, and et al. 2022. "Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Dysregulation of Gene Expression and Lipid Metabolism in HIV+ Patients: Beneficial Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 10: 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105592

APA StyleJiménez-Osorio, A. S., Jaen-Vega, S., Fernández-Martínez, E., Ortíz-Rodríguez, M. A., Martínez-Salazar, M. F., Jiménez-Sánchez, R. C., Flores-Chávez, O. R., Ramírez-Moreno, E., Arias-Rico, J., Arteaga-García, F., & Estrada-Luna, D. (2022). Antiretroviral Therapy-Induced Dysregulation of Gene Expression and Lipid Metabolism in HIV+ Patients: Beneficial Role of Antioxidant Phytochemicals. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(10), 5592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23105592