Delineating the Molecular Events Underlying Development of Prostate Cancer Variants with Neuroendocrine/Small Cell Carcinoma Characteristics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Pathological Definition of Prostate Cancer Variants with NE/SC Characteristics

| Epstein’s Classification | 2016 WHO Classification | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (i) Usual prostate adenocarcinoma with NE differentiation | Adenocarcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation | Morphologically typical acinar or ductal prostate adenocarcinoma with NED only demonstrated by IHC. This type of tumor is molecularly and clinically distinct form (iv) small cell carcinoma and is not associated with poor outcomes [7]. |

| (ii) Adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell NE differentiation | Not defined | Histologically typical prostate adenocarcinoma containing varying proportions of cells with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasmic granules that are chromogranin positive and contain neurosecretory granules. Similar to (i), this type of tumor is molecularly distinct from (iv) [7], and is not associated with poor outcomes [8]. |

| (iii) Carcinoid tumor | Well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor | Well-differentiated NEPCa not closely associated with usual PCa. which are positive for NE markers and negative for PSA. This type of NEPCa is extremely rare and only reported in a limited number of case reports. |

| (iv) Small cell carcinoma | Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | The most well-studied aggressive NEPCa variant that usually arises under selective pressure of ADT (can arise de novo but rare). Defined by characteristic nuclear features, including lack of prominent nucleoli, nuclear molding, fragility, and crush artifact. High N/C ratio, indistinct cell borders, a high mitotic rate and apoptotic bodies are common. |

| (v) Large cell NE carcinoma | Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma | An extremely rare NEPCa variant characterized by large nests with peripheral palisading and often geographic necrosis, prominent nucleoli, vesicular clumpy chromatin, and/or large cell size and abundant cytoplasm, a high mitotic rate. Positive for at least one NE marker by IHC. The largest series of seven cases was reported in 2006 [11]. |

| (vi) Mixed (small or large cell) NE carcinoma-acinar adenocarcinoma | Not defined | Biphasic carcinoma with admixed components of NE (small cell or large cell) carcinoma and usual conventional acinar adenocarcinoma. This type of NEPCa is associated with high-grade aggressive disease. Less frequently, it shows overlap between (iv) small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma and is considered to be in the process of transdifferentiation. |

| Marker | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative/low in NEPCa | PSA | PSA expression is positive throughout disease progression from CSPC to CRPC [12], but positivity decreases in NE/SC [9,10,12]. Yet, a subset of NE/SC (19%) is positive PSA [10]. |

| AR | AR transcriptional activity is low in NE/SC [1]. AR “null” mCRPC is enriched with TP53, RB1 and PTEN alterations [13]. | |

| Nkx 3.1 | Nkx 3.1 is a highly sensitive and specific prostate adenocarcinoma marker [14], and has recently been the most frequently used prostate marker. | |

| PSAP | PSAP expression is positively correlated with PSA expression [15]. | |

| P501s (prostein) | P501s positivity in NE/SC is 28% [10]. P501s is useful in identifying the prostatic origin of NE/SC than PSA [10]. | |

| Cyclin D1 | Cyclin D1 loss was observed in 88% of NE/SC and its loss was highly correlated with Rb loss [16]. | |

| YAP1 | YAP1 is increased in high-grade adeno PCa, but downregulated in NEPCa. Downregulation of YAP1 in NEPCa has been shown in several datasets [17]. | |

| Positive in NEPCa | Chromogranin A | Secretory granules produced by a variety of neural cells [18]. It can be used as a serum marker, too [19]. More than 60% of NEPCa is reported to be positive for CGA [9,10]. |

| Synaptophysin | A vesicle membrane protein that localizes in a variety of neural cells [20]. More than 80% of NEPCa is reported to be positive for SYP [9,10]. | |

| CD56 (Neural cell adhesion molecule) | Membrane-bound glycoprotein predominantly expressed in neural cells. Although positivity in NEPCa is high [9,10], its specificity is low [21]. | |

| TTF-1 (Thyroid transcription factor-1) | TTF-1 is a highly sensitive marker for extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma including NE/SC [9,22]. | |

| FoxA2 | A transcription factor specifically upregulated in NE/SC. Its positivity is reportedly higher than CGA or SYP in NE/SC [23]. | |

| INSM1 (Insulinoma-associated protein 1) | Zinc-finger transcriptional factor elevated in NE/SC [24]. INSM1 is reported to be superior to CGA, SYP and CD56 [24,25]. | |

| Ki67 | A well-known marker of proliferation. Ki67 is >50–80% in NE/SC and LC NE carcinoma but usually not increased in other tumor types such as adenocarcinoma with Paneth cell NED and carcinoid tumor [3]. |

3. Clinical Characteristics of Prostate Cancer Variants with NE/SC Characteristics

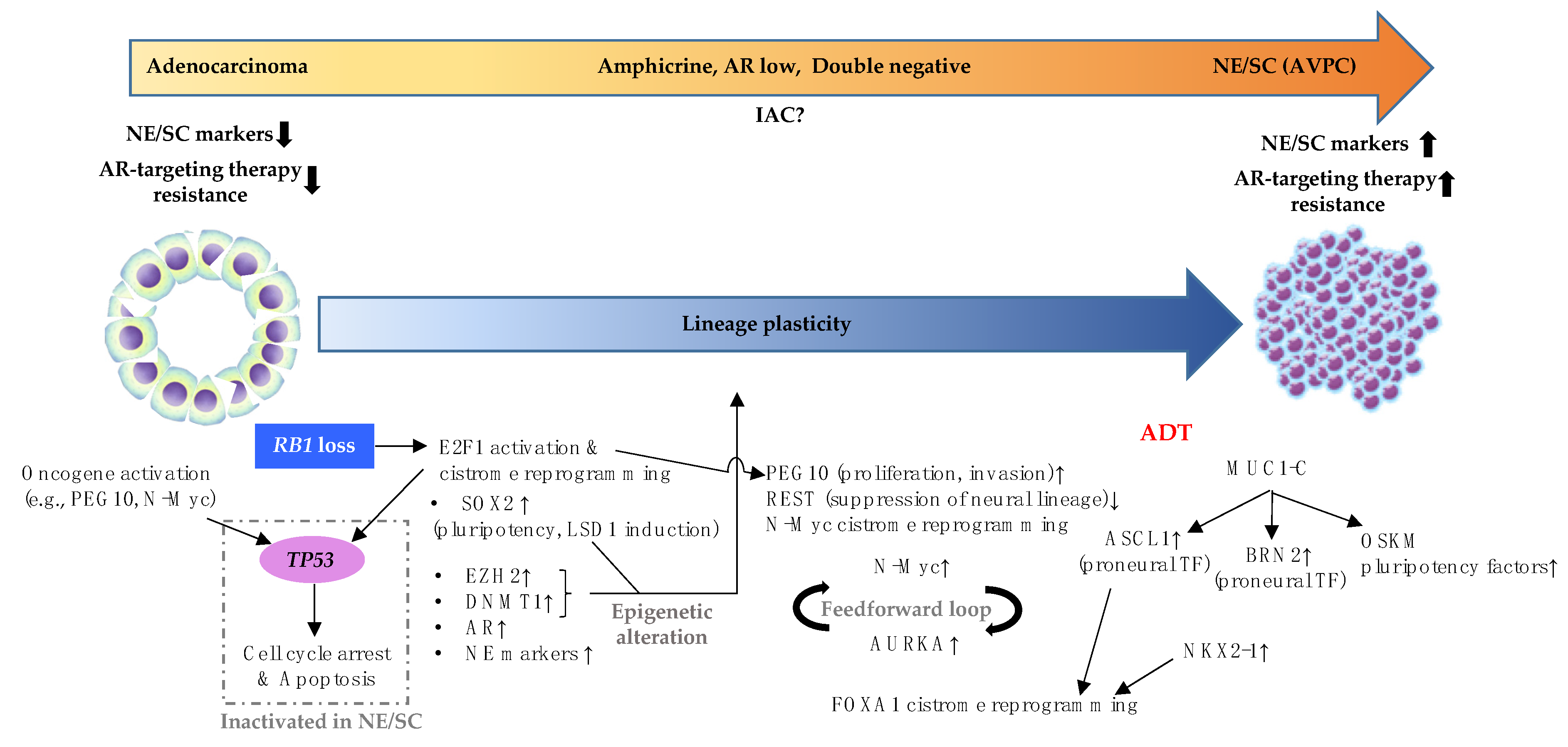

4. Loss of TP53 and RB1 Is a Backbone of NE/SC Development

4.1. Activation and Dysregulation of E2F1 Cistrome Caused by RB1 Loss

4.2. Consequences of Activated and Dysregulated E2F1 Cistrome

4.3. The Role of TP53 Loss in NE/SC Development

5. Additional Alterations Required for NE/SC Development Are Often Associated with ADT

6. Histological Classification of PCa Disease Continuum from Adenocarcinoma to NE/SC and Associated Molecular Events

7. Early Detection of NE/SC

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, R.; Huang, J.; Alumkal, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Feng, F.Y.; Thomas, G.V.; Weinstein, A.S.; Friedl, V.; Zhang, C.; Witte, O.N.; et al. Clinical and Genomic Characterization of Treatment-Emergent Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer: A Multi-institutional Prospective Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2492–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.H.; Beltran, H.; Zoubeidi, A. Cellular plasticity and the neuroendocrine phenotype in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2018, 15, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.I.; Amin, M.B.; Beltran, H.; Lotan, T.L.; Mosquera, J.M.; Reuter, V.E.; Robinson, B.D.; Troncoso, P.; Rubin, M.A. Proposed morphologic classification of prostate cancer with neuroendocrine differentiation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aparicio, A.M.; Harzstark, A.L.; Corn, P.G.; Wen, S.; Araujo, J.C.; Tu, S.M.; Pagliaro, L.C.; Kim, J.; Millikan, R.E.; Ryan, C.; et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy for variant castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2013, 19, 3621–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vlachostergios, P.J.; Puca, L.; Beltran, H. Emerging Variants of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Humphrey, P.A.; Moch, H.; Cubilla, A.L.; Ulbright, T.M.; Reuter, V.E. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part B: Prostate and Bladder Tumours. Eur. Urol. 2016, 70, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaur, H.; Samarska, I.; Lu, J.; Faisal, F.; Maughan, B.L.; Murali, S.; Asrani, K.; Alshalalfa, M.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Epstein, J.I.; et al. Neuroendocrine differentiation in usual-type prostatic adenocarcinoma: Molecular characterization and clinical significance. Prostate 2020, 80, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamas, E.F.; Epstein, J.I. Prognostic significance of paneth cell-like neuroendocrine differentiation in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 980–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.L.; Madeb, R.; Bourne, P.; Lei, J.; Yang, X.; Tickoo, S.; Liu, Z.; Tan, D.; Cheng, L.; Hatem, F.; et al. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate: An immunohistochemical study. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Epstein, J.I. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. A morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 95 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.J.; Humphrey, P.A.; Belani, J.; van der Kwast, T.H.; Srigley, J.R. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of prostate: A clinicopathologic summary of 7 cases of a rare manifestation of advanced prostate cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonk, S.; Kluth, M.; Hube-Magg, C.; Polonski, A.; Soekeland, G.; Makropidi-Fraune, G.; Moller-Koop, C.; Witt, M.; Luebke, A.M.; Hinsch, A.; et al. Prognostic and diagnostic role of PSA immunohistochemistry: A tissue microarray study on 21,000 normal and cancerous tissues. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 5439–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, S.; Vanderbilt, C.; Abida, W.; Fine, S.W.; Tickoo, S.K.; Al-Ahmadie, H.A.; Chen, Y.B.; Sirintrapun, S.J.; Chadalavada, K.; Nanjangud, G.J.; et al. Immunohistochemistry-based assessment of androgen receptor status and the AR-null phenotype in metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurel, B.; Ali, T.Z.; Montgomery, E.A.; Begum, S.; Hicks, J.; Goggins, M.; Eberhart, C.G.; Clark, D.P.; Bieberich, C.J.; Epstein, J.I. NKX3. 1 as a marker of prostatic origin in metastatic tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kristiansen, I.; Stephan, C.; Jung, K.; Dietel, M.; Rieger, A.; Tolkach, Y.; Kristiansen, G. Sensitivity of HOXB13 as a diagnostic immunohistochemical marker of prostatic origin in prostate cancer metastases: Comparison to PSA, prostein, androgen receptor, ERG, NKX3. 1, PSAP, and PSMA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsai, H.; Morais, C.L.; Alshalalfa, M.; Tan, H.-L.; Haddad, Z.; Hicks, J.; Gupta, N.; Epstein, J.I.; Netto, G.J.; Isaacs, W.B. Cyclin D1 loss distinguishes prostatic small-cell carcinoma from most prostatic adenocarcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5619–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, S.; Prieto-Dominguez, N.; Yang, S.; Connelly, Z.M.; StPierre, S.; Rushing, B.; Watkins, A.; Shi, L.; Lakey, M.; Baiamonte, L.B. The expression of YAP1 is increased in high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma but is reduced in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020, 23, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helle, K.B.; Corti, A.; Metz-Boutigue, M.H.; Tota, B. The endocrine role for chromogranin A: A prohormone for peptides with regulatory properties. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2007, 64, 2863–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero-Pous, M.; Hersant, A.M.; Pecking, A.; Bresard-Leroy, M.; Pichon, M.F. Serum chromogranin-A in advanced prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2001, 88, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenmann, B.; Franke, W.W.; Kuhn, C.; Moll, R.; Gould, V.E. Synaptophysin: A marker protein for neuroendocrine cells and neoplasms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 3500–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bösmüller, H.-C.; Wagner, P.; Pham, D.L.; Fischer, A.K.; Greif, K.; Beschorner, C.; Sipos, B.; Fend, F.; Staebler, A. CD56 (neural cell adhesion molecule) expression in ovarian carcinomas: Association with high-grade and advanced stage but not with neuroendocrine differentiation. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoff, S.N.; Lamps, L.W.; Philip, A.T.; Amin, M.B.; Schmidt, R.A.; True, L.D.; Folpe, A.L. Thyroid transcription factor-1 is expressed in extrapulmonary small cell carcinomas but not in other extrapulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Mod. Pathol. 2000, 13, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.W.; Lee, J.K.; Witte, O.N.; Huang, J. FOXA2 is a sensitive and specific marker for small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Shangguan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, J. Insulinoma-associated protein 1 is a novel sensitive and specific marker for small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 79, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, K.; Yasufuku, K.; Kudoh, S.; Motooka, Y.; Sato, Y.; Wakimoto, J.; Kubota, I.; Suzuki, M.; Ito, T. INSM1 is the best marker for the diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumors: Comparison with CGA, SYP and CD56. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2017, 10, 5393–5405. [Google Scholar]

- Conteduca, V.; Oromendia, C.; Eng, K.W.; Bareja, R.; Sigouros, M.; Molina, A.; Faltas, B.M.; Sboner, A.; Mosquera, J.M.; Elemento, O.; et al. Clinical features of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetu, B.; Ro, J.Y.; Ayala, A.G.; Johnson, D.E.; Logothetis, C.J.; Ordonez, N.G. Small cell carcinoma of the prostate. Part I. A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases. Cancer 1987, 59, 1803–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, A.M.; Shen, L.; Tapia, E.L.; Lu, J.F.; Chen, H.C.; Zhang, J.; Wu, G.; Wang, X.; Troncoso, P.; Corn, P.; et al. Combined Tumor Suppressor Defects Characterize Clinically Defined Aggressive Variant Prostate Cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1520–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, L.C.; Halabi, S.; Humeniuk, M.S.; Wu, Y.; Oyekunle, T.; Huang, J.; Anand, M.; Davies, C.; Zhang, T.; Harrison, M.R. Efficacy of the PD-L1 inhibitor avelumab in neuroendocrine or aggressive variant prostate cancer: Results from a phase II, single-arm study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, H.; Prandi, D.; Mosquera, J.M.; Benelli, M.; Puca, L.; Cyrta, J.; Marotz, C.; Giannopoulou, E.; Chakravarthi, B.V.; Varambally, S.; et al. Divergent clonal evolution of castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.Z.; Tsai, S.Y.; Leone, G. Emerging roles of E2Fs in cancer: An exit from cell cycle control. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, A.; Yeow, W.S.; Ertel, A.; Coleman, I.; Clegg, N.; Thangavel, C.; Morrissey, C.; Zhang, X.; Comstock, C.E.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; et al. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor controls androgen signaling and human prostate cancer progression. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 4478–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abeshouse, A.; Ahn, J.; Akbani, R.; Ally, A.; Amin, S.; Andry, C.D.; Annala, M.; Aprikian, A.; Armenia, J.; Arora, A. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell 2015, 163, 1011–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamid, A.A.; Gray, K.P.; Shaw, G.; MacConaill, L.E.; Evan, C.; Bernard, B.; Loda, M.; Corcoran, N.M.; Van Allen, E.M.; Choudhury, A.D.; et al. Compound Genomic Alterations of TP53, PTEN, and RB1 Tumor Suppressors in Localized and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 76, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowalsky, A.G.; Ye, H.; Bhasin, M.; Van Allen, E.M.; Loda, M.; Lis, R.T.; Montaser-Kouhsari, L.; Calagua, C.; Ma, F.; Russo, J.W.; et al. Neoadjuvant-Intensive Androgen Deprivation Therapy Selects for Prostate Tumor Foci with Diverse Subclonal Oncogenic Alterations. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4716–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Julian, L.M.; Blais, A. Transcriptional control of stem cell fate by E2Fs and pocket proteins. Front Genet. 2015, 6, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McNair, C.; Xu, K.; Mandigo, A.C.; Benelli, M.; Leiby, B.; Rodrigues, D.; Lindberg, J.; Gronberg, H.; Crespo, M.; De Laere, B.; et al. Differential impact of RB status on E2F1 reprogramming in human cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schaal, C.M.; Bora-Singhal, N.; Kumar, D.M.; Chellappan, S.P. Regulation of Sox2 and stemness by nicotine and electronic-cigarettes in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kareta, M.S.; Gorges, L.L.; Hafeez, S.; Benayoun, B.A.; Marro, S.; Zmoos, A.F.; Cecchini, M.J.; Spacek, D.; Batista, L.F.; O′Brien, M.; et al. Inhibition of pluripotency networks by the Rb tumor suppressor restricts reprogramming and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem. Cell 2015, 16, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.; Cui, W. Sox2, a key factor in the regulation of pluripotency and neural differentiation. World J. Stem. Cells 2014, 6, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Benelli, M.; Karthaus, W.R.; Hoover, E.; Chen, C.-C.; Wongvipat, J.; Ku, S.-Y.; Gao, D.; Cao, Z. SOX2 promotes lineage plasticity and antiandrogen resistance in TP53-and RB1-deficient prostate cancer. Science 2017, 355, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Geng, X.; Li, M.; Tang, Q.; Wu, C.; Lu, Z. SOX2 has dual functions as a regulator in the progression of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.G.; Chen, W.S.; Li, H.; Foye, A.; Zhang, M.; Sjostrom, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Playdle, D.; Liao, A.; Alumkal, J.J.; et al. The DNA methylation landscape of advanced prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clermont, P.L.; Lin, D.; Crea, F.; Wu, R.; Xue, H.; Wang, Y.; Thu, K.L.; Lam, W.L.; Collins, C.C.; Wang, Y.; et al. Polycomb-mediated silencing in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2015, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bracken, A.P.; Pasini, D.; Capra, M.; Prosperini, E.; Colli, E.; Helin, K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5323–5335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davies, A.; Zoubeidi, A.; Selth, L.A. The epigenetic and transcriptional landscape of neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2020, 27, R35–R50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.I.; Jenner, R.G.; Boyer, L.A.; Guenther, M.G.; Levine, S.S.; Kumar, R.M.; Chevalier, B.; Johnstone, S.E.; Cole, M.F.; Isono, K.; et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 2006, 125, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, T.; Song, H.; Hulsurkar, M.; Su, N.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shao, L.; Ittmann, M. Androgen deprivation promotes neuroendocrine differentiation and angiogenesis through CREB-EZH2-TSP1 pathway in prostate cancers. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin, M.-E.; Hussain, A.; Shore, N.D.; Bradley, B.; Trojer, P.; Lebedinsky, C.; Senderowicz, A.M.; Antonarakis, E.S. A phase 1b/2 study of CPI-1205, a small molecule inhibitor of EZH2, combined with enzalutamide (E) or abiraterone/prednisone (A/P) in patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.K.; Wang, Y.C. Dysregulated transcriptional and post-translational control of DNA methyltransferases in cancer. Cell Biosci. 2014, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vire, E.; Brenner, C.; Deplus, R.; Blanchon, L.; Fraga, M.; Didelot, C.; Morey, L.; Van Eynde, A.; Bernard, D.; Vanderwinden, J.M.; et al. The Polycomb group protein EZH2 directly controls DNA methylation. Nature 2006, 439, 871–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, Y.; Straussman, R.; Keshet, I.; Farkash, S.; Hecht, M.; Zimmerman, J.; Eden, E.; Yakhini, Z.; Ben-Shushan, E.; Reubinoff, B.E.; et al. Polycomb-mediated methylation on Lys27 of histone H3 pre-marks genes for de novo methylation in cancer. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, M.D.; Corella, A.; Coleman, I.; De Sarkar, N.; Kaipainen, A.; Ha, G.; Gulati, R.; Ang, L.; Chatterjee, P.; Lucas, J.; et al. Combined TP53 and RB1 Loss Promotes Prostate Cancer Resistance to a Spectrum of Therapeutics and Confers Vulnerability to Replication Stress. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, L.; Yang, G.; Geng, C.; Luo, Y.; Wu, W.; Manyam, G.C.; Korentzelos, D.; Park, S.; Tang, Z.; et al. PARP Inhibition Suppresses GR-MYCN-CDK5-RB1-E2F1 Signaling and Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2019, 25, 6839–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.H.; Sun, D.; Storck, W.K.; Welker Leng, K.; Jenkins, C.; Coleman, D.J.; Sampson, D.; Guan, X.; Kumaraswamy, A.; Rodansky, E.S.; et al. BET Bromodomain Inhibition Blocks an AR-Repressed, E2F1-Activated Treatment-Emergent Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Lineage Plasticity Program. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 4923–4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Flesken-Nikitin, A.; Corney, D.C.; Wang, W.; Goodrich, D.W.; Roy-Burman, P.; Nikitin, A.Y. Synergy of p53 and Rb deficiency in a conditional mouse model for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 7889–7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harris, S.L.; Levine, A.J. The p53 pathway: Positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nevins, J.R. The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akamatsu, S.; Wyatt, A.W.; Lin, D.; Lysakowski, S.; Zhang, F.; Kim, S.; Tse, C.; Wang, K.; Mo, F.; Haegert, A.; et al. The Placental Gene PEG10 Promotes Progression of Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 922–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petroni, M.; Veschi, V.; Gulino, A.; Giannini, G. Molecular mechanisms of MYCN-dependent apoptosis and the MDM2–p53 pathway: An Achille’s heel to be exploited for the therapy of MYCN-amplified neuroblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beltran, H.; Rickman, D.S.; Park, K.; Chae, S.S.; Sboner, A.; MacDonald, T.Y.; Wang, Y.; Sheikh, K.L.; Terry, S.; Tagawa, S.T.; et al. Molecular characterization of neuroendocrine prostate cancer and identification of new drug targets. Cancer Discov. 2011, 1, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirano, D.; Okada, Y.; Minei, S.; Takimoto, Y.; Nemoto, N. Neuroendocrine differentiation in hormone refractory prostate cancer following androgen deprivation therapy. Eur. Urol. 2004, 45, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, C.; Ceder, J.; Iglesias-Gato, D.; Chuan, Y.C.; Pang, S.T.; Bjartell, A.; Martinez, R.M.; Bott, L.; Helczynski, L.; Ulmert, D.; et al. REST mediates androgen receptor actions on gene repression and predicts early recurrence of prostate cancer. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2014, 42, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Morales, A.; Bergmann, T.B.; Lavallee, C.; Batth, T.S.; Lin, D.; Lerdrup, M.; Friis, S.; Bartels, A.; Kristensen, G.; Krzyzanowska, A.; et al. Proteogenomic Characterization of Patient-Derived Xenografts Highlights the Role of REST in Neuroendocrine Differentiation of Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Labrecque, M.P.; Coleman, I.M.; Brown, L.G.; True, L.D.; Kollath, L.; Lakely, B.; Nguyen, H.M.; Yang, Y.C.; da Costa, R.M.G.; Kaipainen, A.; et al. Molecular profiling stratifies diverse phenotypes of treatment-refractory metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4492–4505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.K.; Phillips, J.W.; Smith, B.A.; Park, J.W.; Stoyanova, T.; McCaffrey, E.F.; Baertsch, R.; Sokolov, A.; Meyerowitz, J.G.; Mathis, C.; et al. N-Myc Drives Neuroendocrine Prostate Cancer Initiated from Human Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berger, A.; Brady, N.J.; Bareja, R.; Robinson, B.; Conteduca, V.; Augello, M.A.; Puca, L.; Ahmed, A.; Dardenne, E.; Lu, X.; et al. N-Myc-mediated epigenetic reprogramming drives lineage plasticity in advanced prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 3924–3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strieder, V.; Lutz, W. E2F proteins regulate MYCN expression in neuroblastomas. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2983–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warner, S.L.; Bearss, D.J.; Han, H.; Von Hoff, D.D. Targeting Aurora-2 Kinase in Cancer1. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003, 2, 589–595. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, T.; Horn, S.; Brockmann, M.; Eilers, U.; Schüttrumpf, L.; Popov, N.; Kenney, A.M.; Schulte, J.H.; Beijersbergen, R.; Christiansen, H. Stabilization of N-Myc is a critical function of Aurora A in human neuroblastoma. Cancer Cell 2009, 15, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kivinummi, K.; Urbanucci, A.; Leinonen, K.; Tammela, T.L.; Annala, M.; Isaacs, W.B.; Bova, G.S.; Nykter, M.; Visakorpi, T. The expression of AURKA is androgen regulated in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraser, J.A.; Sutton, J.E.; Tazayoni, S.; Bruce, I.; Poole, A.V. hASH1 nuclear localization persists in neuroendocrine transdifferentiated prostate cancer cells, even upon reintroduction of androgen. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bishop, J.L.; Thaper, D.; Vahid, S.; Davies, A.; Ketola, K.; Kuruma, H.; Jama, R.; Nip, K.M.; Angeles, A.; Johnson, F. The Master Neural Transcription Factor BRN2 Is an Androgen Receptor–Suppressed Driver of Neuroendocrine Differentiation in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vierbuchen, T.; Ostermeier, A.; Pang, Z.P.; Kokubu, Y.; Sudhof, T.C.; Wernig, M. Direct conversion of fibroblasts to functional neurons by defined factors. Nature 2010, 463, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baca, S.C.; Takeda, D.Y.; Seo, J.H.; Hwang, J.; Ku, S.Y.; Arafeh, R.; Arnoff, T.; Agarwal, S.; Bell, C.; O’Connor, E.; et al. Reprogramming of the FOXA1 cistrome in treatment-emergent neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasumizu, Y.; Rajabi, H.; Jin, C.; Hata, T.; Pitroda, S.; Long, M.D.; Hagiwara, M.; Li, W.; Hu, Q.; Liu, S. MUC1-C regulates lineage plasticity driving progression to neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rajabi, H.; Joshi, M.D.; Jin, C.; Ahmad, R.; Kufe, D. Androgen receptor regulates expression of the MUC1-C oncoprotein in human prostate cancer cells. Prostate 2011, 71, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bluemn, E.G.; Coleman, I.M.; Lucas, J.M.; Coleman, R.T.; Hernandez-Lopez, S.; Tharakan, R.; Bianchi-Frias, D.; Dumpit, R.F.; Kaipainen, A.; Corella, A.N. Androgen receptor pathway-independent prostate cancer is sustained through FGF signaling. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 474–489.e476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, W.; Han, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, B.; Cheng, Y.; Rumandla, A.; Gurrapu, S.; Chakraborty, G.; Su, J.; et al. The Polycomb Repressor Complex 1 Drives Double-Negative Prostate Cancer Metastasis by Coordinating Stemness and Immune Suppression. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.J.; Aggarwal, R.R.; Friedl, V.; Weinstein, A.; Thomas, G.V.; True, L.D.; Foye, A.; Beer, T.M.; Rettig, M.; Gleave, M. Intermediate atypical carcinoma (IAC): A discrete subtype of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) suggesting that treatment-associated small cell/neuroendocrine prostate cancer (t-SCNC) may evolve from mCRPC adenocarcinoma (adeno)—Results from the SU2C/PCF/AACR West Coast Prostate Cancer Dream Team (WCDT). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera, J.M.; Beltran, H.; Park, K.; MacDonald, T.Y.; Robinson, B.D.; Tagawa, S.T.; Perner, S.; Bismar, T.A.; Erbersdobler, A.; Dhir, R. Concurrent AURKA and MYCN gene amplifications are harbingers of lethal treatmentrelated neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 1-IN4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beltran, H.; Romanel, A.; Conteduca, V.; Casiraghi, N.; Sigouros, M.; Franceschini, G.M.; Orlando, F.; Fedrizzi, T.; Ku, S.Y.; Dann, E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA profile recognizes transformation to castration-resistant neuroendocrine prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 1653–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Denmeade, S.R.; Wang, H.; Agarwal, N.; Smith, D.C.; Schweizer, M.T.; Stein, M.N.; Assikis, V.; Twardowski, P.W.; Flaig, T.W.; Szmulewitz, R.Z.; et al. TRANSFORMER: A Randomized Phase II Study Comparing Bipolar Androgen Therapy Versus Enzalutamide in Asymptomatic Men With Castration-Resistant Metastatic Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 1371–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CRPC with at Least One of the Following (Patients with Small-Cell Prostate Carcinoma on Histologic Evaluation Were Not Required to Have Castration-Resistant Disease): |

|---|

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | LTL331 Pre Cx1 | LTL331 Pre Cx2 | LTL331 Post Cx 8wk | LTL331 Post Cx 12wk | LTL331 NE/SC 1 | LTL331 NE/SC 2 |

| ASCL1 | 1.00 | 0.55 | 0.33 | 3.82 | 2.52 | 1.52 |

| AURKA | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 1.75 | 2.20 |

| DNMT1 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.19 | 2.95 | 2.93 |

| E2F1 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 0.36 | 3.37 | 3.79 |

| FOXA1 | 1.00 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| MUC1 | 1.00 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.33 | 2.18 | 1.14 |

| MYCN | 1.00 | 1.16 | 2.27 | 2.34 | 6.82 | 6.84 |

| NKX2-1 | 1.00 | 5.17 | 17.71 | 11.02 | 5.13 | 13.95 |

| PEG10 | 1.00 | 7.31 | 18.68 | 19.82 | 370.77 | 702.05 |

| POU3F2 (BRN2) | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.70 | 1.45 | 146.84 | 210.52 |

| REST | 1.00 | 1.28 | 1.57 | 1.76 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| SOX2 | 1.00 | 2.87 | 1.22 | 12.25 | 6350.99 | 4626.95 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kanayama, M.; Luo, J. Delineating the Molecular Events Underlying Development of Prostate Cancer Variants with Neuroendocrine/Small Cell Carcinoma Characteristics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312742

Kanayama M, Luo J. Delineating the Molecular Events Underlying Development of Prostate Cancer Variants with Neuroendocrine/Small Cell Carcinoma Characteristics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(23):12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312742

Chicago/Turabian StyleKanayama, Mayuko, and Jun Luo. 2021. "Delineating the Molecular Events Underlying Development of Prostate Cancer Variants with Neuroendocrine/Small Cell Carcinoma Characteristics" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 23: 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312742

APA StyleKanayama, M., & Luo, J. (2021). Delineating the Molecular Events Underlying Development of Prostate Cancer Variants with Neuroendocrine/Small Cell Carcinoma Characteristics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(23), 12742. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222312742