From Emollients to Biologicals: Targeting Atopic Dermatitis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Atopic Dermatitis: Molecular and Clinical Features

2.1. Genetic Factors

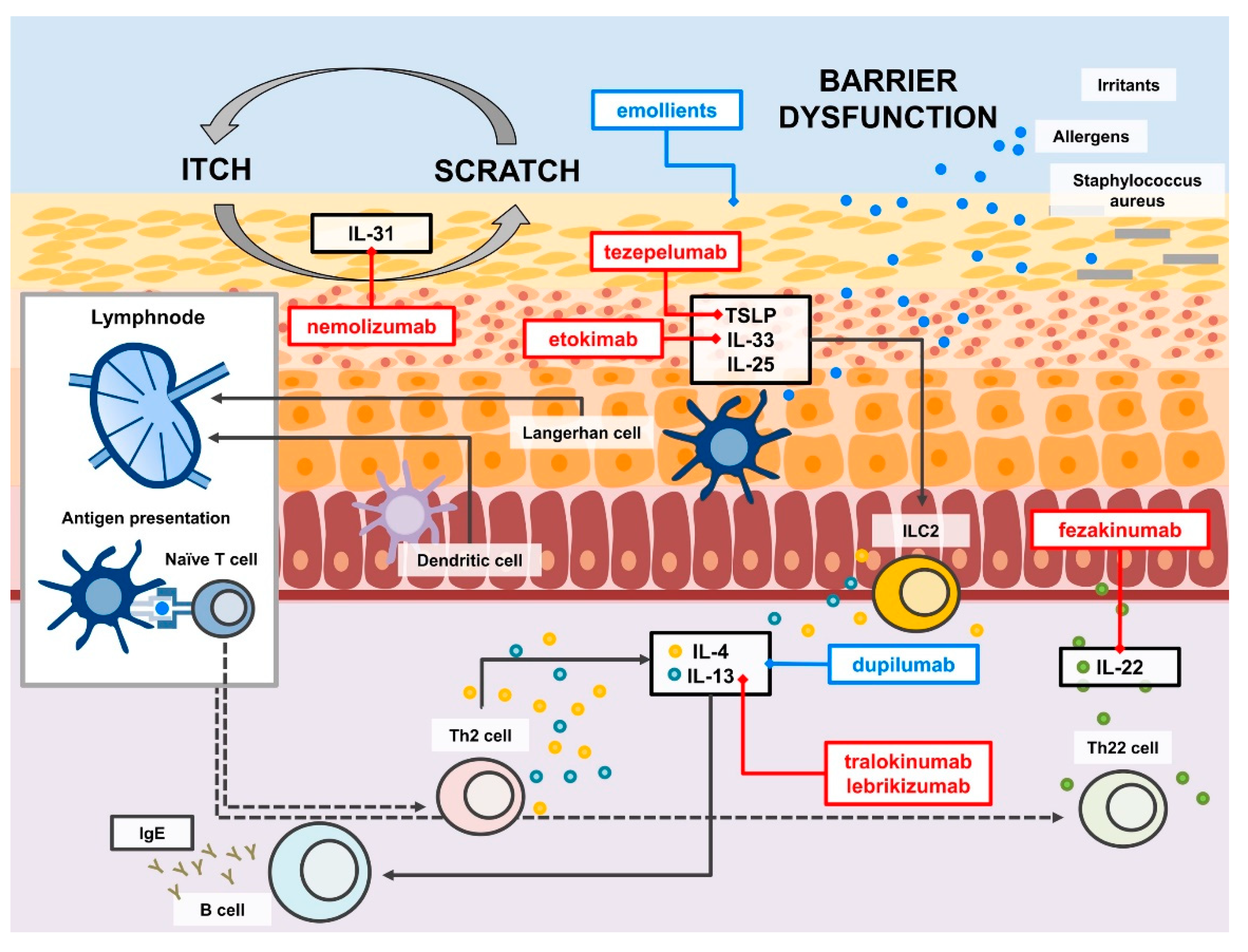

2.2. Type 2 Response and Beyond

2.3. Atopic-Type: Endotypes and Phenotypes in Atopic Dermatitis

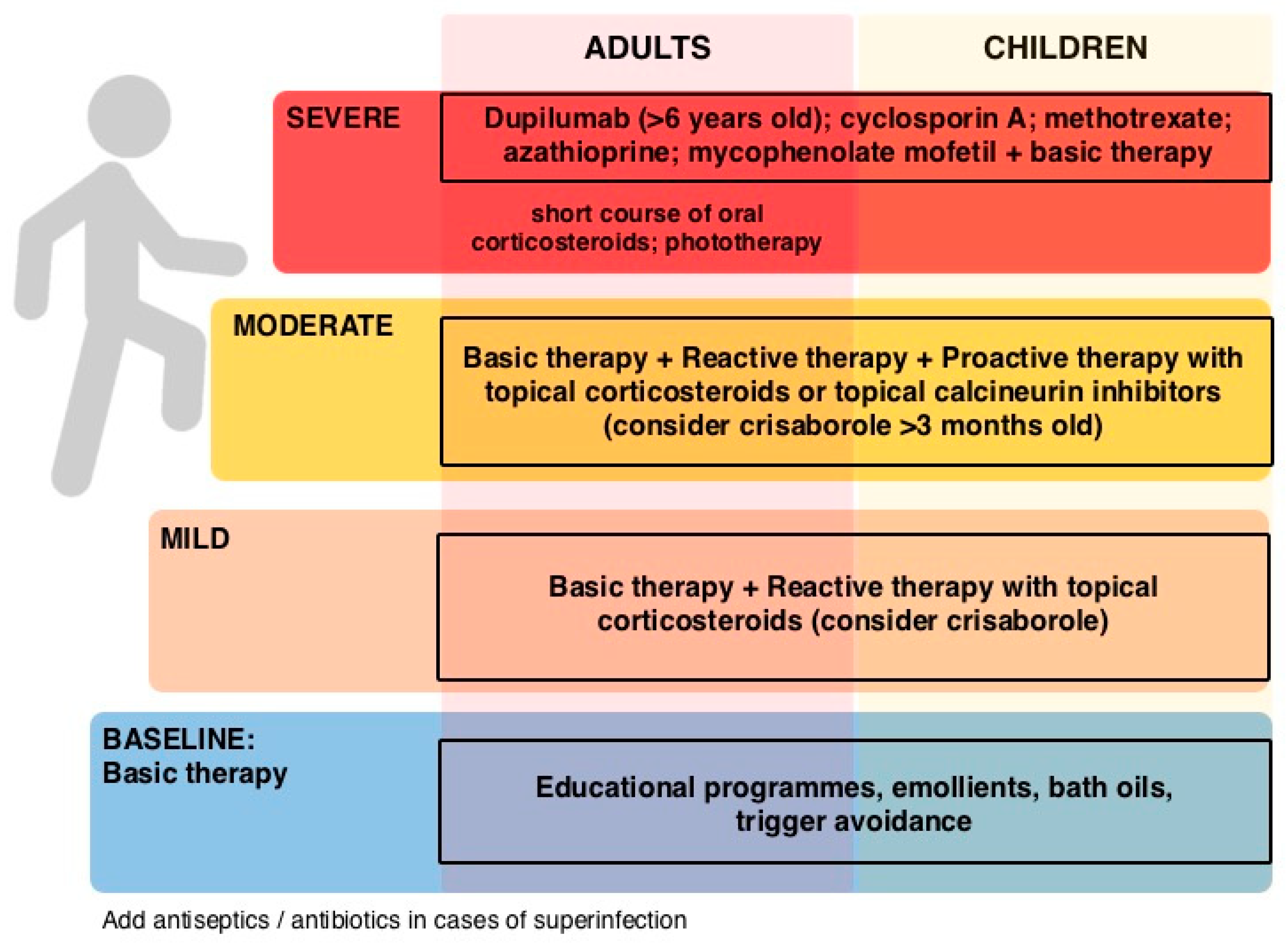

3. Therapeutic Approach to Atopic Dermatitis

3.1. Emollients

3.2. Topical Immunesuppressants

3.3. Topical Antibiotics

3.4. Traditional Systemic Therapy

3.5. Monoclonal Antibodies

3.6. Other Therapies and Upcoming Therapies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weidinger, S.; Beck, L.A.; Bieber, T.; Kabashima, K.; Irvine, A.D. Atopic dermatitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund, S.; von Kobyletzki, L.B.; Svalstedt, M.; Svensson, Å. Prevalence and Incidence of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, A.M. Atopic dermatitis: Burden of illness, quality of life, and associated complications. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017, 38, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ständer, S. Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Løset, M.; Brown, S.J.; Saunes, M.; Hveem, K. Genetics of Atopic Dermatitis: From DNA Sequence to Clinical Relevance. Dermatology 2019, 235, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, A.D.; McLean, W.H.; Leung, D.Y. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drislane, C.; Irvine, A.D. The role of filaggrin in atopic dermatitis and allergic disease. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thepen, T.; Langeveld-Wildschut, E.G.; Bihari, I.C.; van Wichen, D.F.; van Reijsen, F.C.; Mudde, G.C.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A. Biphasic response against aeroallergen in atopic dermatitis showing a switch from an initial TH2 response to a TH1 response in situ: An immunocytochemical study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1996, 97, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivarcsi, A.; Homey, B. Chemokine networks in atopic dermatitis: Traffic signals of disease. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2005, 5, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, M.; Barlow, J.L.; Saunders, S.P.; Xue, L.; Gutowska-Owsiak, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.C.; Johnson, D.; Scanlon, S.T.; McKenzie, A.N.; et al. A role for IL-25 and IL-33-driven type-2 innate lymphoid cells in atopic dermatitis. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2939–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmi, L.; Maggi, L.; Mazzoni, A.; Liotta, F.; Annunziato, F. Biologicals targeting type 2 immunity: Lessons learned from asthma, chronic urticaria and atopic dermatitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 2019, 49, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ho, A.W.; Kupper, T.S. T cells and the skin: From protective immunity to inflammatory skin disorders. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, P.M.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Leung, D.Y. The immunology of atopic dermatitis and its reversibility with broad-spectrum and targeted therapies. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, S65–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werfel, T.; Allam, J.P.; Biedermann, T.; Eyerich, K.; Gilles, S.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Hoetzenecker, W.; Knol, E.; Simon, H.U.; Wollenberg, A.; et al. Cellular and molecular immunologic mechanisms in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gittler, J.K.; Shemer, A.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Gulewicz, K.J.; Wang, C.Q.; Mitsui, H.; Cardinale, I.; de Guzman Strong, C.; Krueger, J.G.; et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renert-Yuval, Y.; Thyssen, J.P.; Bissonnette, R.; Bieber, T.; Kabashima, K.; Hijnen, D.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Biomarkers in atopic dermatitis—A review on behalf of the International Eczema Council. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1174–1190.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnowicki, T.; He, H.; Krueger, J.G.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Atopic dermatitis endotypes and implications for targeted therapeutics. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016, 387, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, Y.W.; Thyssen, J.P.; Silverberg, J.I. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowicki, T.; He, H.; Canter, T.; Han, J.; Lefferdink, R.; Erickson, T.; Rangel, S.; Kameyama, N.; Kim, H.J.; Pavel, A.B.; et al. Evolution of pathologic T-cell subsets in patients with atopic dermatitis from infancy to adulthood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Esaki, H.; Czarnowicki, T.; Gonzalez, J.; Oliva, M.; Talasila, S.; Haugh, I.; Rodriguez, G.; Becker, L.; Krueger, J.G.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; et al. Accelerated T-cell activation and differentiation of polar subsets characterizes early atopic dermatitis development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 1473–1477.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Renert-Yuval, Y.; Del Duca, E.; Pavel, A.B.; Fang, M.; Lefferdink, R.; Wu, J.; Diaz, A.; Estrada, Y.D.; Canter, T.; Zhang, N.; et al. The molecular features of normal and atopic dermatitis skin in infants, children, adolescents, and adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolomoni, G.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Aoki, V.; Kabashima, K.; Deleuran, M.; Puig, L.; Bansal, A.; Rossi, A.B. Nomenclature and clinical phenotypes of atopic dermatitis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2021, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Bieber, T.; Christen-Zaech, S.; Deleuran, M.; Fink-Wagner, A.; Gieler, U.; Girolomoni, G.; Lau, S.; Muraro, A.; et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: Part I. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 657–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wollenberg, A.; Barbarot, S.; Bieber, T.; Christen-Zaech, S.; Deleuran, M.; Fink-Wagner, A.; Gieler, U.; Girolomoni, G.; Lau, S.; Muraro, A.; et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: Part II. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 850–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boguniewicz, M.; Fonacier, L.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Ong, P.Y.; Silverberg, J.; Farrar, J.R. Atopic dermatitis yardstick: Practical recommendations for an evolving therapeutic landscape. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 120, 10–22.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Katoh, N.; Ohya, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Ebihara, T.; Katayama, I.; Saeki, H.; Shimojo, N.; Tanaka, A.; Nakahara, T.; Nagao, M.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of atopic dermatitis 2018. J. Dermatol. 2019, 46, 1053–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oranje, A.P. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: SCORAD Index, objective SCORAD, patient-oriented SCORAD and Three-Item Severity score. Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2011, 41, 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rook, A.; Wilkinson, D.S.; Ebling, F.J.G. Textbook of Dermatology, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1972; Volume 1, p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, R.; Ackerman, A.B.; Sison-Torre, E.Q. Pediatric Dermatology and Dermatopathology; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1990; Volume 1, p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Darsow, U.; Pfab, F.; Valet, M.; Huss-Marp, J.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J.; Ständer, S. Pruritus and atopic dermatitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2011, 41, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, M.; Dittrich, A.M. Expression and function of histamine and its receptors in atopic dermatitis. Mol. Cell. Pediatr. 2015, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsawa, Y.; Hirasawa, N. The role of histamine H1 and H4 receptors in atopic dermatitis: From basic research to clinical study. Allergol. Int. 2014, 63, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thangam, E.B.; Jemima, E.A.; Singh, H.; Baig, M.S.; Khan, M.; Mathias, C.B.; Church, M.K.; Saluja, R. The Role of Histamine and Histamine Receptors in Mast Cell-Mediated Allergy and Inflammation: The Hunt for New Therapeutic Targets. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herman, S.M.; Vender, R.B. Antihistamines in the treatment of dermatitis. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2003, 7, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zuuren, E.J.; Apfelbacher, C.J.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Jupiter, A.; Matterne, U.; Weisshaar, E. No high level evidence to support the use of oral H1 antihistamines as monotherapy for eczema: A summary of a Cochrane systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, A.; Feldman, S.R.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr. An assessment of the use of antihistamines in the management of atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 79, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannuksela, M.; Kalimo, K.; Lammintausta, K.; Mattila, T.; Turjanmaa, K.; Varjonen, E.; Coulie, P.J. Dose ranging study: Cetirizine in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults. Ann. Allergy 1993, 70, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, M.; Tango, T.; Noguchi, T.; Inagi, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Harada, S. Addition of fexofenadine to a topical corticosteroid reduces the pruritus associated with atopic dermatitis in a 1-week randomized, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 148, 1212–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werfel, T.; Layton, G.; Yeadon, M.; Whitlock, L.; Osterloh, I.; Jimenez, P.; Liu, W.; Lynch, V.; Asher, A.; Tsianakas, A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the histamine H4 receptor antagonist ZPL-3893787 in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 1830–1837.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.E.; Leung, D.Y.M. Significance of Skin Barrier Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cork, M.J.; Danby, S.G.; Vasilopoulos, Y.; Hadgraft, J.; Lane, M.E.; Moustafa, M.; Guy, R.H.; Macgowan, A.L.; Tazi-Ahnini, R.; Ward, S.J. Epidermal barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 1892–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zuuren, E.J.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Arents, B.W.M. Emollients and moisturizers for eczema: Abridged Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 1256–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Chalmers, J.R.; Hanifin, J.M.; Thomas, K.S.; Cork, M.J.; McLean, W.H.; Brown, S.J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Williams, H.C. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 818–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chalmers, J.R.; Haines, R.H.; Bradshaw, L.E.; Montgomery, A.A.; Thomas, K.S.; Brown, S.J.; Ridd, M.J.; Lawton, S.; Simpson, E.L.; Cork, M.J.; et al. Daily emollient during infancy for prevention of eczema: The BEEP randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 962–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, K.L.; Kung, J.S.C.; Ng, W.G.G.; Leung, T.F. Emollient treatment of atopic dermatitis: Latest evidence and clinical considerations. Drugs Context 2018, 7, 212530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chalmers, J.R.; Axon, E.; Harvey, J.; Santer, M.; Ridd, M.J.; Lawton, S.; Langan, S.; Roberts, A.; Ahmed, A.; Muller, I.; et al. Different strategies for using topical corticosteroids in people with eczema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 2019, CD013356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleer, M.A.; Jakasa, I.; Stefanovic, N.; McLean, W.H.I.; Kezic, S.; Irvine, A.D. Topical corticosteroids normalize both skin and systemic inflammatory markers in infant atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 185, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Tom, W.L.; Berger, T.G.; Krol, A.; Paller, A.S.; Schwarzenberger, K.; Bergman, J.N.; Chamlin, S.L.; Cohen, D.E.; Cooper, K.D.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wollenberg, A.; Reitamo, S.; Girolomoni, G.; Lahfa, M.; Ruzicka, T.; Healy, E.; Giannetti, A.; Bieber, T.; Vyas, J.; Deleuran, M.; et al. Proactive treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment. Allergy 2008, 63, 742–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; von Kobyletzki, L.; Svensson, A.; Apfelbacher, C. Efficacy and tolerability of proactive treatment with topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors for atopic eczema: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br. J. Dermatol. 2011, 164, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegfried, E.C.; Jaworski, J.C.; Kaiser, J.D.; Hebert, A.A. Systematic review of published trials: Long-term safety of topical corticosteroids and topical calcineurin inhibitors in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Broeders, J.A.; Ahmed Ali, U.; Fischer, G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) comparing topical calcineurin inhibitors with topical corticosteroids for atopic dermatitis: A 15-year experience. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 410–419.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Chen, T.H.; Narala, S.; Chun, K.A.; Two, A.M.; Yun, T.; Shafiq, F.; Kotol, P.F.; Bouslimani, A.; Melnik, A.V.; et al. Antimicrobials from human skin commensal bacteria protect against Staphylococcus aureus and are deficient in atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaah4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrd, A.L.; Deming, C.; Cassidy, S.K.B.; Harrison, O.J.; Ng, W.I.; Conlan, S.; NISC Comparative Sequencing Program; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A.; Kong, H.H. Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis strain diversity underlying pediatric atopic dermatitis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gueniche, A.; Knaudt, B.; Schuck, E.; Volz, T.; Bastien, P.; Martin, R.; Röcken, M.; Breton, L.; Biedermann, T. Effects of nonpathogenic gram-negative bacterium Vitreoscilla filiformis lysate on atopic dermatitis: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 1357–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Skabytska, Y.; Guenova, E.; Chen, K.M.; Frick, J.S.; Kirschning, C.J.; Kaesler, S.; Röcken, M.; Biedermann, T. Nonpathogenic bacteria alleviating atopic dermatitis inflammation induce IL-10-producing dendritic cells and regulatory Tr1 cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harkins, C.P.; McAleer, M.A.; Bennett, D.; McHugh, M.; Fleury, O.M.; Pettigrew, K.A.; Oravcová, K.; Parkhill, J.; Proby, C.M.; Dawe, R.S.; et al. The widespread use of topical antimicrobials enriches for resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients with atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 179, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hajikhani, B.; Goudarzi, M.; Kakavandi, S.; Amini, S.; Zamani, S.; van Belkum, A.; Goudarzi, H.; Dadashi, M. The global prevalence of fusidic acid resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2021, 10, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Gallo, R.L. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 122, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, E.L.; Bruin-Weller, M.; Flohr, C.; Ardern-Jones, M.R.; Barbarot, S.; Deleuran, M.; Bieber, T.; Vestergaard, C.; Brown, S.J.; Cork, M.J.; et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmitt, J.; Schmitt, N.; Meurer, M. Cyclosporin in the treatment of patients with atopic eczema—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijnen, D.J.; ten Berge, O.; Timmer-de Mik, L.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S. Efficacy and safety of long-term treatment with cyclosporin A for atopic dermatitis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2007, 21, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berth-Jones, J.; Takwale, A.; Tan, E.; Barclay, G.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmed, I.; Hotchkiss, K.; Graham-Brown, R.A. Azathioprine in severe adult atopic dermatitis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 147, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, S.F.; Karlsmark, T.; Clemmensen, K.K.; Graversgaard, C.; Ibler, K.S.; Jemec, G.B.; Agner, T. Outcome of treatment with azathioprine in severe atopic dermatitis: A 5-year retrospective study of adult outpatients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1122–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schram, M.E.; Roekevisch, E.; Leeflang, M.M.; Bos, J.D.; Schmitt, J.; Spuls, P.I. A randomized trial of methotrexate versus azathioprine for severe atopic eczema. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haeck, I.M.; Knol, M.J.; Ten Berge, O.; van Velsen, S.G.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.A. Enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium versus cyclosporin A as long-term treatment in adult patients with severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 64, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann-Kollmann, M.; Podda, M.; Ochsendorf, F.; Boehncke, W.H.; Kaufmann, R.; Zollner, T.M. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. 2001, 137, 870–873. [Google Scholar]

- Puar, N.; Chovatiya, R.; Paller, A.S. New treatments in atopic dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agache, I.; Cojanu, C.; Laculiceanu, A.; Rogozea, L. Critical Points on the Use of Biologicals in Allergic Diseases and Asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2020, 12, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renert-Yuval, Y.; Guttman-Yassky, E. New treatments for atopic dermatitis targeting beyond IL-4/IL-13 cytokines. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020, 124, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simpson, E.L.; Bieber, T.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Beck, L.A.; Blauvelt, A.; Cork, M.J.; Silverberg, J.I.; Deleuran, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Lacour, J.P.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Dupilumab versus Placebo in Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2335–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, Y.; Hershey, G.K.K. IL-13 receptor isoforms: Breaking through the complexity. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007, 7, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junttila, I.S. Tuning the Cytokine Responses: An Update on Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 Receptor Complexes. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.D.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Dhingra, N.; Cardinale, I.; Li, X.; Kostic, A.; Ming, J.E.; Radin, A.R.; Krueger, J.G.; Graham, N.; et al. Dupilumab improves the molecular signature in skin of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 1293–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-eczema-drug-dupixent (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Senner, S.; Seegräber, M.; Frey, S.; Kendziora, B.; Eicher, L.; Wollenberg, A. Dupilumab for the treatment of adolescents with atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/dupixent (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Sanofi. Available online: https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-05-26-17-40-00 (accessed on 25 July 2021).

- Gooderham, M.J.; Hong, H.C.; Eshtiaghi, P.; Papp, K.A. Dupilumab: A review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78 (Suppl. S1), S28–S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.L.; Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Boguniewicz, M.; Sher, L.; Gooderham, M.J.; Beck, L.A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Pariser, D.; Blauvelt, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Adolescents with Uncontrolled Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Thaçi, D.; Wollenberg, A.; Cork, M.J.; Arkwright, P.D.; Gooderham, M.; Beck, L.A.; Boguniewicz, M.; Sher, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin-Weller, M.; Thaçi, D.; Smith, C.H.; Reich, K.; Cork, M.J.; Radin, A.; Zhang, Q.; Akinlade, B.; Gadkari, A.; Eckert, L.; et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: A placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br. J. Dermatol. 2018, 178, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuran, M.; Thaçi, D.; Beck, L.A.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Blauvelt, A.; Forman, S.; Bissonnette, R.; Reich, K.; Soong, W.; Hussain, I.; et al. Dupilumab shows long-term safety and efficacy in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis enrolled in a phase 3 open-label extension study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nettis, E.; Bonzano, L.; Patella, V.; Detoraki, A.; Trerotoli, P.; Lombardo, C.; Italian DADReL (Dupilumab Atopic Dermatitis in Real Life) Study Group. Dupilumab-Associated Conjunctivitis in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Multicenter Real-Life Experience. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 30, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halling, A.S.; Loft, N.; Silverberg, J.I.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Thyssen, J.P. Real-world evidence of dupilumab efficacy and risk of adverse events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinlade, B.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Simpson, E.L.; Blauvelt, A.; Cork, M.J.; Prens, E.; Asbell, P.; Akpek, E.; Corren, J.; et al. Conjunctivitis in dupilumab clinical trials. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, A.; Simpson, E.L.; Paller, A.S.; Siegfried, E.C.; Blauvelt, A.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Corren, J.; Sher, L.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Chen, Z.; et al. Conjunctivitis in Dupilumab Clinical Trials for Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis or Asthma. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popiela, M.Z.; Barbara, R.; Turnbull, A.M.J.; Corden, E.; Martinez-Falero, B.S.; O’Driscoll, D.; Ardern-Jones, M.R.; Hossain, P.N. Dupilumab-associated ocular surface disease: Presentation, management and long-term sequelae. Eye 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cork, M.J.; Thaçi, D.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Arkwright, P.D.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Akinlade, B.; Boklage, S.; Guillemin, I.; Kosloski, M.P.; et al. Dupilumab provides favourable long-term safety and efficacy in children aged ≥6 to <12 years with uncontrolled severe atopic dermatitis: Results from an open-label phase IIa study and subsequent phase III open-label extension study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 857–870. [Google Scholar]

- Agache, I.; Song, Y.; Posso, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Rocha, C.; Solà, I.; Beltran, J.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Brockow, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A systematic review for the EAACI biologicals guidelines. Allergy 2021, 76, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, A.M.; Ellis, A.G.; Bohdanowicz, M.; Mashayekhi, S.; Yiu, Z.Z.N.; Rochwerg, B.; Di Giorgio, S.; Arents, B.W.M.; Burton, T.; Spuls, P.I.; et al. Systemic Immunomodulatory Treatments for Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spekhorst, L.S.; Ariëns, L.F.M.; van der Schaft, J.; Bakker, D.S.; Kamsteeg, M.; Oosting, A.J.; de Ridder, I.; Sloeserwij, A.; Romeijn, G.L.E.; de Graaf, M.; et al. Two-year drug survival of dupilumab in a large cohort of difficult-to-treat adult atopic dermatitis patients compared to cyclosporine A and methotrexate: Results from the BioDay registry. Allergy 2020, 75, 2376–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bello, G.; Maurelli, M.; Schena, D.; Girolomoni, G.; Gisondi, P. Drug survival of dupilumab compared to cyclosporin in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Kabashima, K.; Bieber, T. Therapeutic pipeline for atopic dermatitis: End of the drought? J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ratchataswan, T.; Banzon, T.M.; Thyssen, J.P.; Weidinger, S.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Phipatanakul, W. Biologics for Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: Current Status and Future Prospect. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Qi, F.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, B. Biological Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Dermatology 2021, 237, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollenberg, A.; Howell, M.D.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Silverberg, J.I.; Kell, C.; Ranade, K.; Moate, R.; van der Merwe, R. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with tralokinumab, an anti-IL-13 mAb. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wollenberg, A.; Blauvelt, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Worm, M.; Lynde, C.; Lacour, J.P.; Spelman, L.; Katoh, N.; Saeki, H.; Poulin, Y.; et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br. J. Dermatol. 2021, 184, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Blauvelt, A.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Paller, A.S.; Armstrong, A.W.; Drew, J.; Gopalan, R.; Simpson, E.L. Efficacy and Safety of Lebrikizumab, a High-Affinity Interleukin 13 Inhibitor, in Adults with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Phase 2b Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Brunner, P.M.; Neumann, A.U.; Khattri, S.; Pavel, A.B.; Malik, K.; Singer, G.K.; Baum, D.; Gilleaudeau, P.; Sullivan-Whalen, M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of fezakinumab (an IL-22 monoclonal antibody) in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by conventional treatments: A randomized, double-blind, phase 2a trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 872–881.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brunner, P.M.; Pavel, A.B.; Khattri, S.; Leonard, A.; Malik, K.; Rose, S.; Jim On, S.; Vekaria, A.S.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Singer, G.K.; et al. Baseline IL-22 expression in patients with atopic dermatitis stratifies tissue responses to fezakinumab. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Parnes, J.R.; She, D.; Crouch, S.; Rees, W.; Mo, M.; van der Merwe, R. Tezepelumab, an anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: A randomized phase 2a clinical trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1013–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.L.; Gutowska-Owsiak, D.; Hardman, C.S.; Westmoreland, M.; MacKenzie, T.; Cifuentes, L.; Waithe, D.; Lloyd-Lavery, A.; Marquette, A.; Londei, M.; et al. Proof-of-concept clinical trial of etokimab shows a key role for IL-33 in atopic dermatitis pathogenesis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaax2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, B.; Pavel, A.B.; Li, R.; Kimmel, G.; Nia, J.; Hashim, P.; Kim, H.J.; Chima, M.; Vekaria, A.S.; Estrada, Y.; et al. Phase 2 randomized, double-blind study of IL-17 targeting with secukinumab in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandeghinste, N.; Klattig, J.; Jagerschmidt, C.; Lavazais, S.; Marsais, F.; Haas, J.D.; Auberval, M.; Lauffer, F.; Moran, T.; Ongenaert, M.; et al. Neutralization of IL-17C Reduces Skin Inflammation in Mouse Models of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1555–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Krueger, J.G. IL-17C: A Unique Epithelial Cytokine with Potential for Targeting across the Spectrum of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1467–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Pavel, A.B.; Zhou, L.; Estrada, Y.D.; Zhang, N.; Xu, H.; Peng, X.; Wen, H.C.; Govas, P.; Gudi, G.; et al. GBR 830, an anti-OX40, improves skin gene signatures and clinical scores in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 482–493.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furue, M.; Furue, M. OX40L-OX40 Signaling in Atopic Dermatitis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, H.; Iizuka, H.; Nemoto, O.; Shimabe, M.; Furukawa, Y.; Kikuta, N.; Ootaki, K. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of repeated intravenous infusions of KHK4083, a fully human anti-OX40 monoclonal antibody, in Japanese patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020, 99, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzicka, T.; Hanifin, J.M.; Furue, M.; Pulka, G.; Mlynarczyk, I.; Wollenberg, A.; Galus, R.; Etoh, T.; Mihara, R.; Yoshida, H.; et al. Anti-Interleukin-31 Receptor A Antibody for Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabashima, K.; Furue, M.; Hanifin, J.M.; Pulka, G.; Wollenberg, A.; Galus, R.; Etoh, T.; Mihara, R.; Nakano, M.; Ruzicka, T. Nemolizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Randomized, phase II, long-term extension study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 1121–1130.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Pinter, A.; Pulka, G.; Poulin, Y.; Bouaziz, J.D.; Wollenberg, A.; Murrell, D.F.; Alexis, A.; Lindsey, L.; Ahmad, F.; et al. Phase 2B randomized study of nemolizumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and severe pruritus. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabashima, K.; Matsumura, T.; Komazaki, H.; Kawashima, M.; Nemolizumab-JP01 Study Group. Trial of Nemolizumab and Topical Agents for Atopic Dermatitis with Pruritus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Tom, W.L.; Lebwohl, M.G.; Blumenthal, R.L.; Boguniewicz, M.; Call, R.S.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Forsha, D.W.; Rees, W.C.; Simpson, E.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 494–503.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Call, R.S.; Forsha, D.W.; Fowler, J., Jr.; Hebert, A.A.; Spellman, M.; Gold, L.F.S.; Van Syoc, M.; Zane, L.T.; Tschen, E. Long-term safety of crisaborole ointment 2% in children and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 641–649.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bissonnette, R.; Pavel, A.B.; Diaz, A.; Werth, J.L.; Zang, C.; Vranic, I.; Purohit, V.S.; Zielinski, M.A.; Vlahos, B.; Estrada, Y.D.; et al. Crisaborole and atopic dermatitis skin biomarkers: An intrapatient randomized trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1274–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solimani, F.; Meier, K.; Ghoreschi, K. Emerging Topical and Systemic JAK Inhibitors in Dermatology. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bieber, T. Leveraging the nice face of Janus kinase inhibition-ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 489–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartron, A.M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Roh, Y.S.; Kwatra, M.M.; Kwatra, S.G. Janus kinase inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: A promising treatment modality. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 820–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Sun, X.; Zhao, K.; Meng, F.; Li, L.; Mu, Z.; Han, X. Efficacy and Safety of Janus Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dermatology 2021, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, H.; Nemoto, O.; Igarashi, A.; Saeki, H.; Oda, M.; Kabashima, K.; Nagata, T. Phase 2 clinical study of delgocitinib ointment in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1575–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagawa, H.; Nemoto, O.; Igarashi, A.; Saeki, H.; Kaino, H.; Nagata, T. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 823–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakagawa, H.; Nemoto, O.; Igarashi, A.; Saeki, H.; Murata, R.; Kaino, H.; Nagata, T. Long-term safety and efficacy of delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. 2020, 47, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhillon, S. Delgocitinib: First Approval. Drugs 2020, 80, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.S.; Howell, M.D.; Sun, K.; Papp, K.; Nasir, A.; Kuligowski, M.E.; INCB 18424-206 Study Investigators. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with ruxolitinib cream (JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor) or triamcinolone cream. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, B.S.; Sun, K.; Papp, K.; Venturanza, M.; Nasir, A.; Kuligowski, M.E. Effects of ruxolitinib cream on pruritus and quality of life in atopic dermatitis: Results from a phase 2, randomized, dose-ranging, vehicle- and active-controlled study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 1305–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bissonnette, R.; Papp, K.A.; Poulin, Y.; Gooderham, M.; Raman, M.; Mallbris, L.; Wang, C.; Purohit, V.; Mamolo, C.; Papacharalambous, J.; et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: A phase IIa randomized trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2016, 175, 902–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, E.L.; Lacour, J.P.; Spelman, L.; Galimberti, R.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Bissonnette, R.; King, B.A.; Thyssen, J.P.; Silverberg, J.I.; Bieber, T.; et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: Results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 183, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, J.I.; Simpson, E.L.; Wollenberg, A.; Bissonnette, R.; Kabashima, K.; DeLozier, A.M.; Sun, L.; Cardillo, T.; Nunes, F.P.; Reich, K. Long-term Efficacy of Baricitinib in Adults with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis Who Were Treatment Responders or Partial Responders: An Extension Study of 2 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 12, e211273. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, K.; Kabashima, K.; Peris, K.; Silverberg, J.I.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Bieber, T.; Kaszuba, A.; Kolodsick, J.; Yang, F.E.; Gamalo, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Baricitinib Combined with Topical Corticosteroids for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 1333–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegels, D.; Heratizadeh, A.; Abraham, S.; Binnmyr, J.; Brockow, K.; Irvine, A.D.; Halken, S.; Mortz, C.G.; Flohr, C.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; et al. Systemic treatments in the management of atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2021, 76, 1053–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Torres, T. Selective JAK1 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: Focus on Upadacitinib and Abrocitinib. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2020, 21, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, K.; Teixeira, H.D.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Bieber, T.; Soong, W.; Kabashima, K.; Werfel, T.; Zeng, J.; Huang, X.; Hu, X.; et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD Up): Results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2169–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Thaçi, D.; Pangan, A.L.; Hong, H.C.; Papp, K.A.; Reich, K.; Beck, L.A.; Mohamed, M.F.; Othman, A.A.; Anderson, J.K.; et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bieber, T.; Simpson, E.L.; Silverberg, J.I.; Thaçi, D.; Paul, C.; Pink, A.E.; Kataoka, Y.; Chu, C.Y.; DiBonaventura, M.; Rojo, R.; et al. Abrocitinib versus Placebo or Dupilumab for Atopic Dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Sinclair, R.; Forman, S.; Wollenberg, A.; Aschoff, R.; Cork, M.; Bieber, T.; Thyssen, J.P.; Yosipovitch, G.; Flohr, C.; et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, R.; Maari, C.; Forman, S.; Bhatia, N.; Lee, M.; Fowler, J.; Tyring, S.; Pariser, D.; Sofen, H.; Dhawan, S.; et al. The oral Janus kinase/spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor ASN002 demonstrates efficacy and improves associated systemic inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pavel, A.B.; Song, T.; Kim, H.J.; Del Duca, E.; Krueger, J.G.; Dubin, C.; Peng, X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, N.; Estrada, Y.D.; et al. Oral Janus kinase/SYK inhibition (ASN002) suppresses inflammation and improves epidermal barrier markers in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Treatment | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Topical treatments | |

| Emollients | Use daily |

| Topical corticosteroids | Short-term in the acute phase/proactive therapy |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | Skin sensitive areas/proactive therapy |

| Crisaborole | Mild-moderate AD |

| Topical JAK-inhibitors | Delgocitinib approved in Japan |

| Systemic treatments | |

| Corticosteroids | Short-term in severe AD |

| Cyclosporine A | Chronic severe AD |

| Azathioprine Mycophenolate mofetil | If cyclosporine A is not effective or not indicated |

| Methotrexate | Long-term maintenance |

| Dupilumab | Moderate-severe AD (>12 years) Severe AD (>6 years) |

| Oral JAK-inhibitors | Baricitinib in moderate-severe AD |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salvati, L.; Cosmi, L.; Annunziato, F. From Emollients to Biologicals: Targeting Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910381

Salvati L, Cosmi L, Annunziato F. From Emollients to Biologicals: Targeting Atopic Dermatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(19):10381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910381

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalvati, Lorenzo, Lorenzo Cosmi, and Francesco Annunziato. 2021. "From Emollients to Biologicals: Targeting Atopic Dermatitis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 19: 10381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910381

APA StyleSalvati, L., Cosmi, L., & Annunziato, F. (2021). From Emollients to Biologicals: Targeting Atopic Dermatitis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(19), 10381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms221910381