Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome

Abstract

:1. Introduction

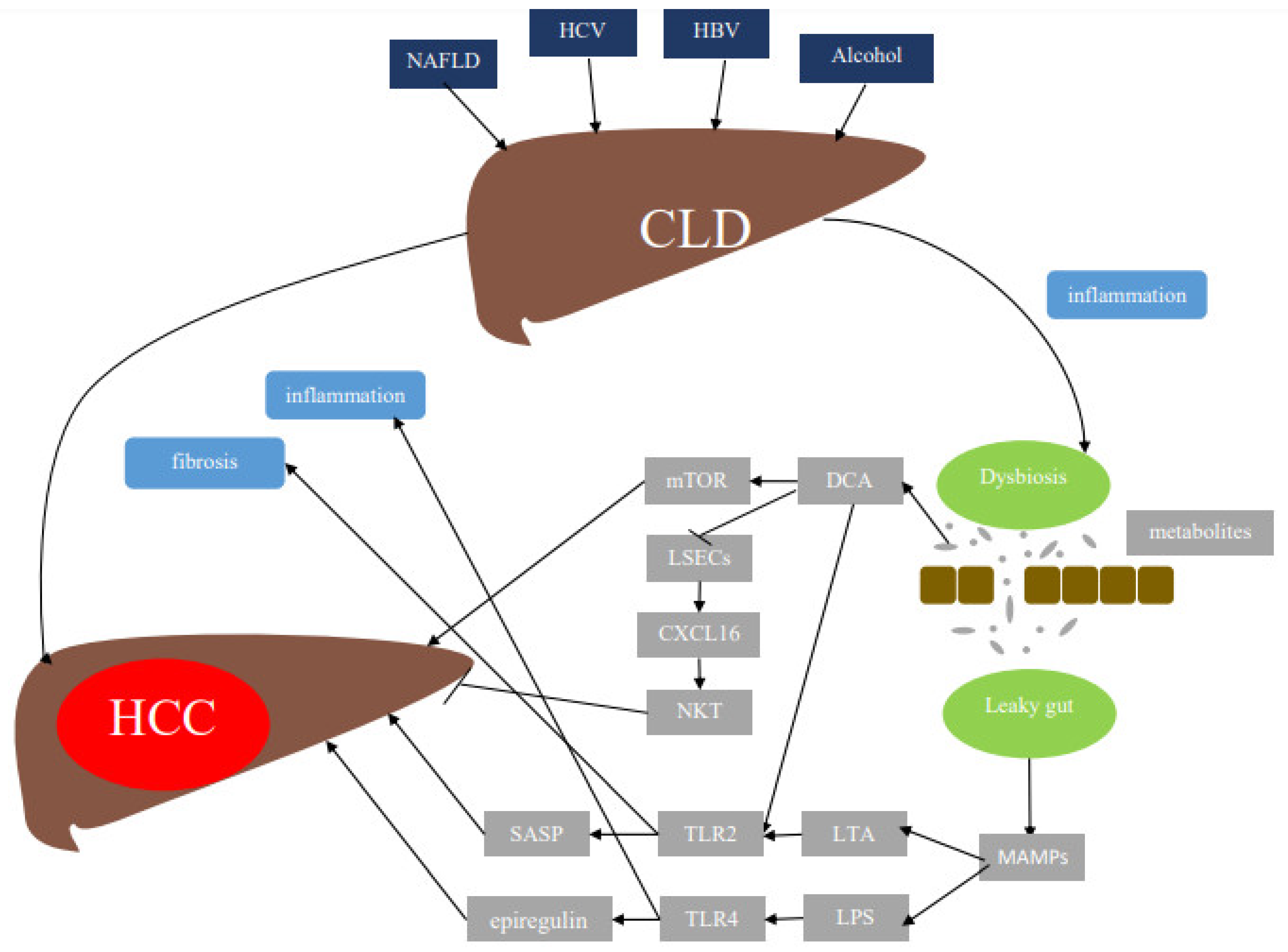

2. Role of Gut Microbiota

3. Mechanisms by Which Gut Microbiota Induce HCC

4. Changes in Gut Microbiota Associated with Different Liver Diseases

5. Strategies to Manipulate Gut Microbiome for HCC Treatment/Prevention

5.1. Probiotics

5.2. Fecal Microbial Transplantation (FMT)

5.3. Prebiotics

6. Immunotherapy for HCC

7. Influence of Gut Microbiome on Cancer Immunotherapy

8. Impact of Gut Microbiome on HCC Immunotherapy and Potential Use of Gut Microbiome Targeting Approaches

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| MAMPs | Microbiota-associated molecular patterns |

| DCA | Deoxycholic acid |

| LSEC | Liver sinusoidal cells |

| NKT | Natural killer T cell |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| HSC | Hepatic stellate cells |

| LTA | Lipoteichoic acid |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| CLD | Chronic liver disease |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 (IL-6) |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| OS | Overall survival |

| CR | Complete response |

| VEGFR | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

| PDGFR | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| SIRT1 | Silent information regulator 1 |

| CCL4 | Carbon tetrachloride |

| HepG2 | Hepatocellular carcinoma cells |

| DEN | N-diethylnitrosamine |

References

- Ferlay, J.; Ervik, M.; Lam, F.; Colombet, M.; Mery, L.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Soerjomataram, I.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, J.K.; Holmes, E.; Kinross, J.; Burcelin, R.; Gibson, G.; Jia, W.; Pettersson, S. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science 2012, 336, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wan, M.L.; El-Nezami, H. Targeting gut microbiota in hepatocellular carcinoma: Probiotics as a novel therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stärkel, P.; Schnabl, B. Bidirectional Communication between Liver and Gut during Alcoholic Liver Disease. Semin Liver Dis. 2016, 36, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compare, D.; Coccoli, P.; Rocco, A.; Nardone, O.; De Maria, S.; Cartenì, M.; Nardone, G. Gut–liver axis: The impact of gut microbiota on non alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandl, K.; Kumar, V.; Eckmann, L. Gut-liver axis at the frontier of host-microbial interactions. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 312, G413–G419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, L.J.; Barnes, M.; Tang, H.; Pritchard, M.T.; Nagy, L.E. Kupffer cells in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 2013, 3, 785–797. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, P.J.; Adams, D.H. Gut–liver immunity. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1187–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chung, H.; Pamp, S.J.; Hill, J.A.; Surana, N.K.; Edelman, S.M.; Troy, E.B.; Reading, N.C.; Villablanca, E.J.; Wang, S.; Mora, J.R. Gut immune maturation depends on colonization with a host-specific microbiota. Cell 2012, 149, 1578–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitkunat, K.; Schumann, S.; Petzke, K.J.; Blaut, M.; Loh, G.; Klaus, S. Effects of dietary inulin on bacterial growth, short-chain fatty acid production and hepatic lipid metabolism in gnotobiotic mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2015, 26, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chandrashekharappa, S.; Bodduluri, S.R.; Baby, B.V.; Hegde, B.; Kotla, N.G.; Hiwale, A.A.; Saiyed, T.; Patel, P.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshimoto, S.; Loo, T.M.; Atarashi, K.; Kanda, H.; Sato, S.; Oyadomari, S.; Iwakura, Y.; Oshima, K.; Morita, H.; Hattori, M. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature 2013, 499, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Han, M.; Heinrich, B.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Sandhu, M.; Agdashian, D.; Terabe, M.; Berzofsky, J.A.; Fako, V. Gut microbiome–mediated bile acid metabolism regulates liver cancer via NKT cells. Science 2018, 360, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loo, T.M.; Kamachi, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kanda, H.; Arai, Y.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Iwama, A.; Koga, T.; Sugimoto, Y. Gut microbiota promotes obesity-associated liver cancer through PGE2-mediated suppression of antitumor immunity. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 522–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yamada, S.; Takashina, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Nagamine, R.; Saito, Y.; Kamada, N.; Saito, H. Bile acid metabolism regulated by the gut microbiota promotes non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-associated hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 9925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, V.; San Yeoh, B.; Chassaing, B.; Xiao, X.; Saha, P.; Olvera, R.A.; Lapek, J.D., Jr.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.-B.; Hao, S. Dysregulated microbial fermentation of soluble fiber induces cholestatic liver cancer. Cell 2018, 175, 679–694. e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dapito, D.H.; Mencin, A.; Gwak, G.-Y.; Pradere, J.-P.; Jang, M.-K.; Mederacke, I.; Caviglia, J.M.; Khiabanian, H.; Adeyemi, A.; Bataller, R. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, I.; Blaser, M.J. The human microbiome: At the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Acharya, C.; Bajaj, J.S. Altered microbiome in patients with cirrhosis and complications. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Zheng, R.D.; Sun, X.Q.; Ding, W.J.; Wang, X.Y.; Fan, J.G. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis. Int. 2017, 16, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jiang, X.; Cao, M.; Ge, J.; Bao, Q.; Tang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, L. Altered Fecal Microbiota Correlates with Liver Biochemistry in Nonobese Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, J.; Mueller, O.; Barret, M.; Machado, M.; Fizanne, L.; Araujo-Perez, F.; Guy, C.D.; Seed, P.C.; Rawls, J.F.; David, L.A. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology 2016, 63, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Loomba, R.; Seguritan, V.; Li, W.; Long, T.; Klitgord, N.; Bhatt, A.; Dulai, P.S.; Caussy, C.; Bettencourt, R.; Highlander, S.K. Gut microbiome-based metagenomic signature for non-invasive detection of advanced fibrosis in human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1054–1062. e1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, D.; Ahmed, A.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Tang, L.; Mo, D.; Ma, Y.; Xin, Y. Comparison of the gut microbe profiles and numbers between patients with liver cirrhosis and healthy individuals. Curr. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Lu, H.; Wang, B.; Chen, Y.; Lei, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Li, L. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2011, 54, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, N.; Yang, F.; Li, A.; Prifti, E.; Chen, Y.; Shao, L.; Guo, J.; Le Chatelier, E.; Yao, J.; Wu, L. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature 2014, 513, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Paroni Sterbini, F.; Petito, V. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with gut microbiota profile and inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2019, 69, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Chen, S.; Fu, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Yang, B.; Ou, Q. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in patients with hepatitis B virus–induced chronic liver disease covering chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Viral Hepat. 2020, 27, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Yan, X.; Zou, D.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Han, J.; Huang, L. Abnormal fecal microbiota community and functions in patients with hepatitis B liver cirrhosis as revealed by a metagenomic approach. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Shao, L.; Zhang, R. Gut microbiome analysis as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2019, 68, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, F.; Zhuang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Mao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Alteration in gut microbiota associated with hepatitis B and non-hepatitis virus related hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Pathog. 2019, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Wang, B.; Fu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, L. Changes of fecal Bifidobacterium species in adult patients with hepatitis B virus-induced chronic liver disease. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, D.; Whelan, K.; Rossi, M.; Morrison, M.; Holtmann, G.; Kelly, J.T.; Shanahan, E.R.; Staudacher, H.M.; Campbell, K.L. Dietary fiber intervention on gut microbiota composition in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rivière, A.; Selak, M.; Lantin, D.; Leroy, F.; De Vuyst, L. Bifidobacteria and butyrate-producing colon bacteria: Importance and strategies for their stimulation in the human gut. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.; Baker, S.S.; Gill, C.; Liu, W.; Alkhouri, R.; Baker, R.D.; Gill, S.R. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: A connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology 2013, 57, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Ling, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cai, T.; Yuan, H.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Xu, K. Dysbiosis of intestinal microbiota associated with inflammation involved in the progression of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas 2015, 44, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, N.; Dzutsev, A.; Stewart, C.A.; Smith, L.; Bouladoux, N.; Weingarten, R.A.; Molina, D.A.; Salcedo, R.; Back, T.; Cramer, S. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment. Science 2013, 342, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillère, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, J.L.; Wilson, I.D.; Teare, J.; Marchesi, J.R.; Nicholson, J.K.; Kinross, J.M. Gut microbiota modulation of chemotherapy efficacy and toxicity. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 356–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervin, S.M.; Hanley, R.P.; Lim, L.; Walton, W.G.; Pearce, K.H.; Bhatt, A.P.; James, L.I.; Redinbo, M.R. Targeting regorafenib-induced toxicity through inhibition of gut microbial β-glucuronidases. ACS Chem. Biol. 2019, 14, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kelly, C.P.; Bakirtzi, K.; Gálvez, J.A.V.; Lyras, D.; Mileto, S.J.; Larcombe, S.; Xu, H.; Yang, X.; Shields, K.S. Clostridium difficile toxins induce VEGF-A and vascular permeability to promote disease pathogenesis. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, S.H.; Choe, K.; Hong, S.P.; Jeong, S.H.; Mäkinen, T.; Kim, K.S.; Alitalo, K.; Surh, C.D.; Koh, G.Y.; Song, J.H. Gut microbiota regulates lacteal integrity by inducing VEGF-C in intestinal villus macrophages. EMBO Rep. 2019, 20, e46927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leblanc, A.D.M.; Matar, C.; Perdigón, G. The application of probiotics in cancer. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 98, S105–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Sung, C.Y.J.; Lee, N.; Ni, Y.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Panagiotou, G.; El-Nezami, H. Probiotics modulated gut microbiota suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1306–E1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elshaer, A.M.; El-Kharashi, O.A.; Hamam, G.G.; Nabih, E.S.; Magdy, Y.M.; Abd El Samad, A.A. Involvement of TLR4/ CXCL9/ PREX-2 pathway in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and the promising role of early administration of lactobacillus plantarum in Wistar rats. Tissue Cell 2019, 60, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, Z.; Rahaie, M.; Alizadeh, A.M. Different anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobactrum bifidioum in hepatocellular carcinoma cancer mouse through impact on microRNAs and their target genes. J. Nutr. Intermed. Metab. 2019, 16, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, M.; Živković, M.; Jovanović, J.A.; Tolinački, M.; Sinadinović, M.; Rajić, J.; Uskoković, A.; Dinić, S.; Grdović, N.; Golić, N.; et al. Oral administration of probiotic Lactobacillus paraplantarum BGCG11 attenuates diabetes-induced liver and kidney damage in rats. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 38, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hesketh, J.; Huang, D.; Gan, F.; Hao, S.; Tang, S.; Guo, Y.; Huang, K. Protective effects of selenium-glutathione-enriched probiotics on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Kang, J.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Park, I.H.; Ha, N.J. Antiviral activity of Bifidobacterium adolescentis SPM0212 against Hepatitis B virus. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2013, 36, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, K.M.; Lwin, A.A.; Kyaw, Y.Y.; Tun, W.M.; Fukada, K.; Goshima, A.; Shimada, T.; Okada, S. Safety and long-term effect of the probiotic FK-23 in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Biosci. MicrobiotaFood Health 2016, 35, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allam, N.; Salem, M.; Hassan, E.; Nabieh, M. Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacteria spp having antibacterial and antiviral effects on chronic HCV infection. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2019, 13, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nabavi, S.; Rafraf, M.; Somi, M.H.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Effects of probiotic yogurt consumption on metabolic factors in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 7386–7393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.B.; Jun, D.W.; Kang, B.-K.; Lim, J.H.; Lim, S.; Chung, M.-J. Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study of a Multispecies Probiotic Mixture in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duseja, A.; Acharya, S.K.; Mehta, M.; Chhabra, S.; Rana, S.; Das, A.; Dattagupta, S.; Dhiman, R.K.; Chawla, Y.K. High potency multistrain probiotic improves liver histology in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A randomised, double-blind, proof of concept study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2019, 6, e000315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nduti, N.; McMillan, A.; Seney, S.; Sumarah, M.; Njeru, P.; Mwaniki, M.; Reid, G. Investigating probiotic yoghurt to reduce an aflatoxin B1 biomarker among school children in eastern Kenya: Preliminary study. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 63, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Parmar, I.; Neir, S.V. Biotransformation of Cranberry Proanthocyanidins to Probiotic Metabolites by Lactobacillus rhamnosus Enhances Their Anticancer Activity in HepG2 Cells In Vitro. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 4750795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, J.-W.; Kuo, C.-H.; Kuo, F.-C.; Wang, Y.-K.; Hsu, W.-H.; Yu, F.-J.; Hu, H.-M.; Hsu, P.-I.; Wang, J.-Y.; Wu, D.-C. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Review and update. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, S23–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbo, S.; Ianiro, G.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Past, present and future perspectives. Minerva Gastroenterol. E Dietol. 2017, 63, 420–430. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, L.P.; Bouter, K.E.; de Vos, W.M.; Borody, T.J.; Nieuwdorp, M. Therapeutic potential of fecal microbiota transplantation. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambalam, P.; Raman, M.; Purama, R.K.; Doble, M. Probiotics, prebiotics and colorectal cancer prevention. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2016, 30, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandair, D.S.; Rossi, R.E.; Pericleous, M.; Whyand, T.; Caplin, M. The impact of diet and nutrition in the prevention and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 8, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvesh, A.S.; Bishayee, A. Chemopreventive and therapeutic potential of tea polyphenols in hepatocellular cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoysungnoen, P.; Wirachwong, P.; Changtam, C.; Suksamrarn, A.; Patumraj, S. Anti-cancer and anti-angiogenic effects of curcumin and tetrahydrocurcumin on implanted hepatocellular carcinoma in nude mice. World J. Gastroenterol. WJG 2008, 14, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Liu, Y.; Jia, L.; Zhou, H.-M.; Kong, Y.; Yang, G.; Jiang, L.-P.; Li, Q.-J.; Zhong, L.-F. Curcumin induces apoptosis through mitochondrial hyperpolarization and mtDNA damage in human hepatoma G2 cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007, 43, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, S.-E.; Kuo, M.; Hsu, C.; Chen, C.; Lin, J.; Lai, G.; Hsieh, C.; Cheng, A. Curcumin-containing diet inhibits diethylnitrosamine-induced murine hepatocarcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yeh, C.-B.; Hsieh, M.-J.; Lin, C.-W.; Chiou, H.-L.; Lin, P.-Y.; Chen, T.-Y.; Yang, S.-F. The antimetastatic effects of resveratrol on hepatocellular carcinoma through the downregulation of a metastasis-associated protease by SP-1 modulation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Flórez, S.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, B.N.; Sánchez-Campos, S.; González-Gallego, J.; Tuñón, M.A.J. Quercetin attenuates nuclear factor-κB activation and nitric oxide production in interleukin-1β–activated rat hepatocytes. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waidmann, O. Recent developments with immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2018, 18, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Sangro, B.; Yau, T.; Crocenzi, T.S.; Kudo, M.; Hsu, C.; Kim, T.-Y.; Choo, S.-P.; Trojan, J.; Welling, T.H., 3rd. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): An open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocenzi, T.S.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Yau, T.C.; Melero, I.; Sangro, B.; Kudo, M.; Hsu, C.; Trojan, J.; Kim, T.-Y.; Choo, S.-P.; et al. Nivolumab (nivo) in sorafenib (sor)-naive and -experienced pts with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): CheckMate 040 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 4013–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, T.; Park, J.; Finn, R.; Cheng, A.-L.; Mathurin, P.; Edeline, J.; Kudo, M.; Han, K.-H.; Harding, J.; Merle, P. CheckMate 459: A randomized, multi-center phase III study of nivolumab (NIVO) vs sorafenib (SOR) as first-line (1L) treatment in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC). Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v874–v875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.X.; Finn, R.S.; Edeline, J.; Cattan, S.; Ogasawara, S.; Palmer, D.; Verslype, C.; Zagonel, V.; Fartoux, L.; Vogel, A. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): A non-randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 940–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, P.; Edeline, J.; Bouattour, M.; Cheng, A.-L.; Chan, S.L.; Yau, T.; Garrido, M.; Knox, J.J.; Daniele, B.; Zhu, A.X.; et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) vs placebo (pbo) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) previously treated with sorafenib: Updated data from the randomized, phase III KEYNOTE-240 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 268–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Ikeda, M.; Zhu, A.X.; Sung, M.W.; Baron, A.D.; Kudo, M.; Okusaka, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumada, H.; Kaneko, S. Phase Ib Study of Lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab in Patients With Unresectable Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishvaian, M.J.; Lee, M.S.; Ryoo, B.Y.; Stein, S.; Lee, K.H.; Verret, W.; Spahn, J.; Shao, H.; Liu, B.; Iizuka, K.; et al. Updated safety and clinical activity results from a phase Ib study of atezolizumab + bevacizumab in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, viii718–viii719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.S.; Qin, S.; Ikeda, M.; Galle, P.R.; Ducreux, M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kudo, M.; Breder, V.; Merle, P.; Kaseb, A.O. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1894–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yau, T.; Kang, Y.-K.; Kim, T.-Y.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; Santoro, A.; Sangro, B.; Melero, I.; Kudo, M.; Hou, M.-M.; Matilla, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Nivolumab Plus Ipilimumab in Patients With Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Previously Treated With Sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, e204564–e204564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Corrales, L.; Hubert, N.; Williams, J.B.; Aquino-Michaels, K.; Earley, Z.M.; Benyamin, F.W.; Lei, Y.M.; Jabri, B.; Alegre, M.-L. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti–PD-L1 efficacy. Science 2015, 350, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopalakrishnan, V.; Spencer, C.N.; Nezi, L.; Reuben, A.; Andrews, M.; Karpinets, T.; Prieto, P.; Vicente, D.; Hoffman, K.; Wei, S. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti–PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matson, V.; Fessler, J.; Bao, R.; Chongsuwat, T.; Zha, Y.; Alegre, M.-L.; Luke, J.J.; Gajewski, T.F. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti–PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science 2018, 359, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaput, N.; Lepage, P.; Coutzac, C.; Soularue, E.; Le Roux, K.; Monot, C.; Boselli, L.; Routier, E.; Cassard, L.; Collins, M.; et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1368–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmed, J.; Kumar, A.; Parikh, K.; Anwar, A.; Knoll, B.M.; Puccio, C.; Chun, H.; Fanucchi, M.; Lim, S.H. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics impacts outcome in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1507670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Carmagnani Pestana, R.; Hess, K.; Viola, G.M.; Subbiah, V. Impact of antibiotic use on survival in patients with advanced cancers treated on immune checkpoint inhibitor phase I clinical trials. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 2396–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huemer, F.; Rinnerthaler, G.; Westphal, T.; Hackl, H.; Hutarew, G.; Gampenrieder, S.P.; Weiss, L.; Greil, R. Impact of antibiotic treatment on immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy in advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 16512–16520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baruch, E.N.; Youngster, I.; Ben-Betzalel, G.; Ortenberg, R.; Lahat, A.; Katz, L.; Adler, K.; Dick-Necula, D.; Raskin, S.; Bloch, N.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2021, 371, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzutsev, A.; Badger, J.H.; Perez-Chanona, E.; Roy, S.; Salcedo, R.; Smith, C.K.; Trinchieri, G. Microbes and cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, T.; Tu, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Tan, D.; Jiang, W.; Cai, S.; Zhao, P.; Song, R. Gut microbiome affects the response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| CLD Type | Microorganism | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NAFLD | ↓ Prevotella ↑ Proteobacteria ↑ Fusobacteria ↑ Erysipelotrichaceae ↑ Enterobacteriaceae ↑ Lachnospiraceae ↑ Escherichia Shigella ↑ Streptococcaceae | [21] |

| ↓ Firmicutes ↑ Bacteroidetes | [22] | |

| ↓ Prevotella ↑ Bacteroides ↑ Ruminococcus | [23] | |

| ↑ Escherichia coli ↑ Bacteroides vulgatus | [24] | |

| Cirrhosis | ↑ Enterobacteriaceae ↑ Enterococcus | [25] |

| ↓ Bacteroidetes ↑ Proteobacteria ↑ Fusobacteria ↑ Enterobacteriaceae ↑ Streptococcaceae ↑ Veillonellaceae | [26] | |

|

↓ Bacteroides ↑ Prevotella ↑ Clostridium ↑ Streptococcus ↑ Veillonella | [27] | |

| ↓ Akkermansia ↑ Enterobacteriaceae ↑ Streptococcaceae | [28] | |

| HBV |

↓ Bifidobacterium ↓ Clostridiaceae ↓ Clostridia ↓ Ruminococcus ↑ Klebsiella ↑ Escherichia coli ↑ Proteus ↑ Enterobacter | [29] |

|

↓ Bacteroidetes ↑ Proteobacteria | [30] | |

| Cirrhosis + HCC |

↓ Bifidobacterium ↑ Bacteroidetes ↑ Ruminococcaceae | [28] |

| HBV + HCC |

↓ Verrucomicrobia ↑ Actinobacteria | [31] |

| HCC |

↓ Faecalibacterium ↓ Ruminococcus ↓ Ruminoclostridium ↑ Escherichia-Shigella ↑ Enterococcus | [32] |

| Treatment | Patients | Clinical Phase | PFS (Months, 95% CI) | Median OS (Months, 95% CI) | RR (%, 95% CI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab | Advanced HCC | Phase I/II | 3.4 (1.6–6.9), for DS 4.1 (3.7–5.5), for EX | 15.0 (9.6–20.2), for DS NR, for EX | 15% (6–28), for DS 20% (15–26), for EX | [71] |

| Nivolumab | Advanced HCC | Phase III | 3.7 (3.1–3.9) | 16.4 (13.9–18.4) | 15% | [73] |

| Sorafenib | 3.8 (3.7–4.5) | 14.7 (11.9–17.2) (HR 0.84, p = 0.0419) | 7% | |||

| Nivolumab plus Ipilumab | Advanced HCC | Phase I/II | 22.8 (95% CI, 9.4 NR) | 32% (95% CI, 20–47%) | [79] | |

| Pembrolizumab | Advanced HCC | Phase II | 4.8 (3.4–6.6) | 12.9 (9.7–15.5) | 17% (11–26) | [74] |

| Pembrolizumab | Second-line, Advanced HCC | Phase III | 3.0 (2.8–4.1) | 13.9 (11.6–16.0) | 18.3 (14.0–23.4) | [75] |

| Placebo | 2.8 (2.5–4.1) | 10.6 (8.3–13.5) (HR 0.781, p = 0.023) | 4.4 (1.6–9.4) | |||

| Pembrolizumab plus Lenvatinib | Unresectable HCC | Phase Ib | 9.3 | 22.0 | 46.0% (36.0–56.3) | [76] |

| Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab | Unresectable HCC | Phase 1b | 34% | [77] | ||

| Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab | Unresectable HCC | Phase III | 6.8 (5.7–8.3) | 67.2% (61.3–73.1) | [78] | |

| Sorafenib | 4.3 (4.0–5.6) (HR 0.59, p < 0.001) | 54.6% (45.2–64.0) 12 months response |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Temraz, S.; Nassar, F.; Kreidieh, F.; Mukherji, D.; Shamseddine, A.; Nasr, R. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157800

Temraz S, Nassar F, Kreidieh F, Mukherji D, Shamseddine A, Nasr R. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(15):7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157800

Chicago/Turabian StyleTemraz, Sally, Farah Nassar, Firas Kreidieh, Deborah Mukherji, Ali Shamseddine, and Rihab Nasr. 2021. "Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 15: 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157800

APA StyleTemraz, S., Nassar, F., Kreidieh, F., Mukherji, D., Shamseddine, A., & Nasr, R. (2021). Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy and the Potential Influence of Gut Microbiome. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15), 7800. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22157800