Abstract

The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a homodimeric vasoactive glycoprotein, is the key mediator of angiogenesis. Angiogenesis, the formation of new blood vessels, is responsible for a wide variety of physio/pathological processes, including cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Cardiomyocytes (CM), the main cell type present in the heart, are the source and target of VEGF-A and express its receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, on their cell surface. The relationship between VEGF-A and the heart is double-sided. On the one hand, VEGF-A activates CM, inducing morphogenesis, contractility and wound healing. On the other hand, VEGF-A is produced by CM during inflammation, mechanical stress and cytokine stimulation. Moreover, high concentrations of VEGF-A have been found in patients affected by different CVD, and are often correlated with an unfavorable prognosis and disease severity. In this review, we summarized the current knowledge about the expression and effects of VEGF-A on CM and the role of VEGF-A in CVD, which are the most important cause of disability and premature death worldwide. Based on clinical studies on angiogenesis therapy conducted to date, it is possible to think that the control of angiogenesis and VEGF-A can lead to better quality and span of life of patients with heart disease.

1. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been discovered to be a permeability-enhancing agent leading to the disruption of intercellular contacts and the increase of permeability [1]. VEGF family, in humans, consists of five separate gene products: VEGF-A, VEGF-B and Placental growth factor, which are key regulators of blood vessel growth; and VEGF-C and VEGF-D, which modulate lymphangiogenesis [2]. VEGF-A, a homodimeric glycoprotein of approximately 45 kDa [3], is the key to vasculogenesis (the de novo formation of vessels) and angiogenesis (the formation of new vessels from preformed vasculature) [4,5]. VEGF-A induces cellular chemotaxis [6] and the expression of plasminogen activators [7] and collagenases [8] in endothelial cells (EC). VEGF-A promotes blood vessel growth and remodeling processes, and it also provides survival and mitogenic stimuli for EC [9,10,11]. During inflammation and tumorigenesis, sequestered VEGF can be released by proteases including matrix metalloproteinases [12,13], plasmin, urokinase-type plasminogen activator, elastase and tissue kallikrein. These proteases, affecting VEGF-A activity through VEGF-A cleavage, activation and degradation, can both promote angiogenesis, for example as a key step in carcinogenesis, and suppress VEGF’s angiogenic effects [14].

In humans, VEGF-A gene locus is on chromosome 6p21.1 and contains eight exons and seven introns. Through alternative splicing, human VEGF-A is represented by multiple isoforms [15,16]. The four major expressed variants are 121, 165, 189 and 206 amino acids long, with the VEGF-A165 representing the predominant species of VEGF-A [2,17,18,19,20]. The larger isoforms, VEGF-A165, VEGF-A189 and VEGF-A206, are basic and bind to isolated heparin and heparin proteoglycans distributed on cellular surfaces and extracellular matrices [21,22]. The VEGF short form, VEGF-A121, is acidic and is more freely diffusible [20,21]. VEGF gene expression is upregulated by a variety of factors, such as growth factors (i.e., fibroblast growth factors, epidermal growth factor, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [23,24,25,26,27,28].

VEGF isoforms, with their differences in biotransport, sequestration and receptor binding, induce a spectrum of vascular phenotypes [20] from the malformed, edematous, hypovascular networks of VEGF-A120 (VEGF-A121 in human) due to dilated and poorly branched vessel generation [29] to the stable, thin and branching vessels of VEGF-A188 (VEGF-A189 in human) [30]. These vascular phenotypes are related to the ability of VEGF-A isoforms to induce the sprouting, migratory phenotype. VEGF-A165 (VEGF-A164 in mouse) is the first isoform characterized and as a potent stimulator of angiogenesis [20]. Its expression is adequate neonatal growth and has been well documented in tissues during physiological and/or pathological conditions [2,17].

The physiological effects of VEGF-A are driven by the binding to two homologous VEGF-A receptors. These receptors are known as VEGFR1 (Flt-1 in mice) and VEGFR2 (Flk-1; KDR) [31,32]. They areencoded by separate genes and are members of the class IV receptor tyrosine kinase family [33]. The expression of VEGFR has been demonstrated on EC, macrophages, mast cells and smooth muscle cells [34,35,36,37]. Although VEGFR1 binds VEGF-A with high affinity, it is believed to act primarily by modulating the availability of VEGF-A for binding to VEGFR2 [38,39,40,41]. Receptors for the VEGF-A, apart from those bound to cellular membranes, also occur in soluble form [42]. The soluble VEGFR1 (sVEGFR1) and sVEGFR2 receptors, binding VEGF-A before it reaches membrane-bound receptors on surface cells, are regarded as physiological inhibitors of the processes of angiogenesis and neoangiogenesis [43].

2. Cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes (CM), also known as myocardiocytes or cardiac myocytes, are the muscle cells that belong to the heart muscle [44]. CM are contractile cells that, through their autorhythmicity and coordinated action with other CM, enable the heart to function as a pump [45]. This mechanism ensures that sufficient oxygenated blood and metabolites reach the tissues to meet the body’s needs, whether at rest or during exercise [46]. To fulfill these functions, the CMare equipped with highly specialized subcellular machinery [44,47]. The first one of this system is the basement membrane, whose functions are to separate the intracellular structure from the extracellular environment, promote the exchange of macromolecules and catch ions, such as calcium [48,49,50].

A specialized structure of the CM is the sarcolemma. The sarcolemma controls the type of molecules that enters the cell [51,52] and guarantees the contraction and relaxation of the cells [53,54]. The CM cytoskeleton forms an important structural link between the extracellular environment and the contractile apparatus, and it can influence CM geometry and function through the phosphorylation of some of its proteins [55]. Myofilaments, contractile proteins formed from myosin and actin, are additional important subcellular structures. The interaction of these motor proteins guarantees the contraction of the muscle that allows blood to be pumped throughout the body [56,57,58]. Finally, CM contain a large number of mitochondria, which maintain high levels of ATP required by the cells to promote the contraction and relaxation of the heart muscle [59,60].

CM produce and secrete several mediators such as adiponectin [61], regenerating islet-derived protein 3-β [62], TNF-α, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interferon γ [63], transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [64], IL-6 and IL-11 [65,66]. It has been shown that CM are also a source of angiogenic factors, such as angiopoietin 1 (ANGPT1), ANGPT2 [67,68] and mainly VEGF-A [69].

3. Cardiomyocytes as Producers of VEGF-A

CM are a source of VEGF-A, which performs several functions in the heart. VEGF-A is the main regulator of vascular permeability and of angiogenesis [70]. In the mouse model, CM-specific deletion of VEGF-A alters negatively vasculogenesis/angiogenesis and causes a thinner ventricular wall [71], confirming mutual signaling from the CM to the EC during heart development. Interestingly, in mice lacking the VEGF-A the myocardial microvasculature is underdeveloped, but the coronary artery structure is preserved, involving a different signaling pathway for vasculogenesis/angiogenesis in the myocardium and epicardial coronary arteries [72]. Mice with CM-specific deletion of VEGF-A164 and VEGF-A188 isoforms show impaired myocardial angiogenesis with subsequent ischemic cardiomyopathy and heart failure [73]. These mice also exhibit heart capillaries that are more irregular, tortuous and dilated, indicating an incomplete vessel remodeling. Therefore, VEGF-A induces myocardiac angiogenesis and enhances vascular permeability and EC proliferation [73].

In mouse model, the production of VEGF-A from CM also blocks the transformation of cardiac endocardial into mesenchymal [74]. This mechanism plays an important role in cardiac cushion formation and requires gentle control of VEGF-A concentration [74,75,76]. In the same animal model, low levels of VEGF-A induce the transformation of cardiac endocardial into mesenchymal, whereas high levels of VEGF-A block this transformation [77]. Interestingly, this signal induced by the production of VEGF-A from CM for endocardial–mesenchymal transformation may be regulated by an endothelial-derived feedback process through the calcineurin/NFAT pathway [78], demonstrating the importance of EC–CM interactions for cardiac morphogenesis [67].

In rat CM, mechanical stress regulates VEGF-A expression, while stretch improves the secretion [79]. Factors involved in the upregulation of VEGF-A expression in mice hypertrophied CM include hypoxia-inducible factor 1-α [80,81,82], but also NFκB [83], TGF-β [84] and endothelin-1 [85]. Mice with CM lacking GATA4, a transcription factor that directly binds the VEGF-A promoter, show a poor capillary density in their hearts, while overexpression of GATA4 markedly improves cardiac vascularization and function following myocardial infarction by promoting angiogenesis (via VEGF-A production), hypertrophy, and inhibiting apoptosis [86,87]. In addition to GATA4, GATA6 and GATA2 also control angiogenesis [88,89,90]. In CM, the activation p38MAPK induces VEGF-A production, whereas its secretion occurs in an Sp1-dependent manner [91,92]. In this regard, the heart of mice with p38-inactivated CM exhibits compromised compensatory angiogenesis after pressure overload, and it is prone to early onset of heart failure. In summary, p38αMAPK plays a critical role in the cross dialogue between CM and vascularization by regulating stress-induced VEGF-A expression and secretion in murine CM [93].

To date, there are no data on the expression and release of VEGF in human CM. Further studies are required to define the mechanistic role of VEGF-A in humans and whether this knowledge may be beneficial in specific patient populations.

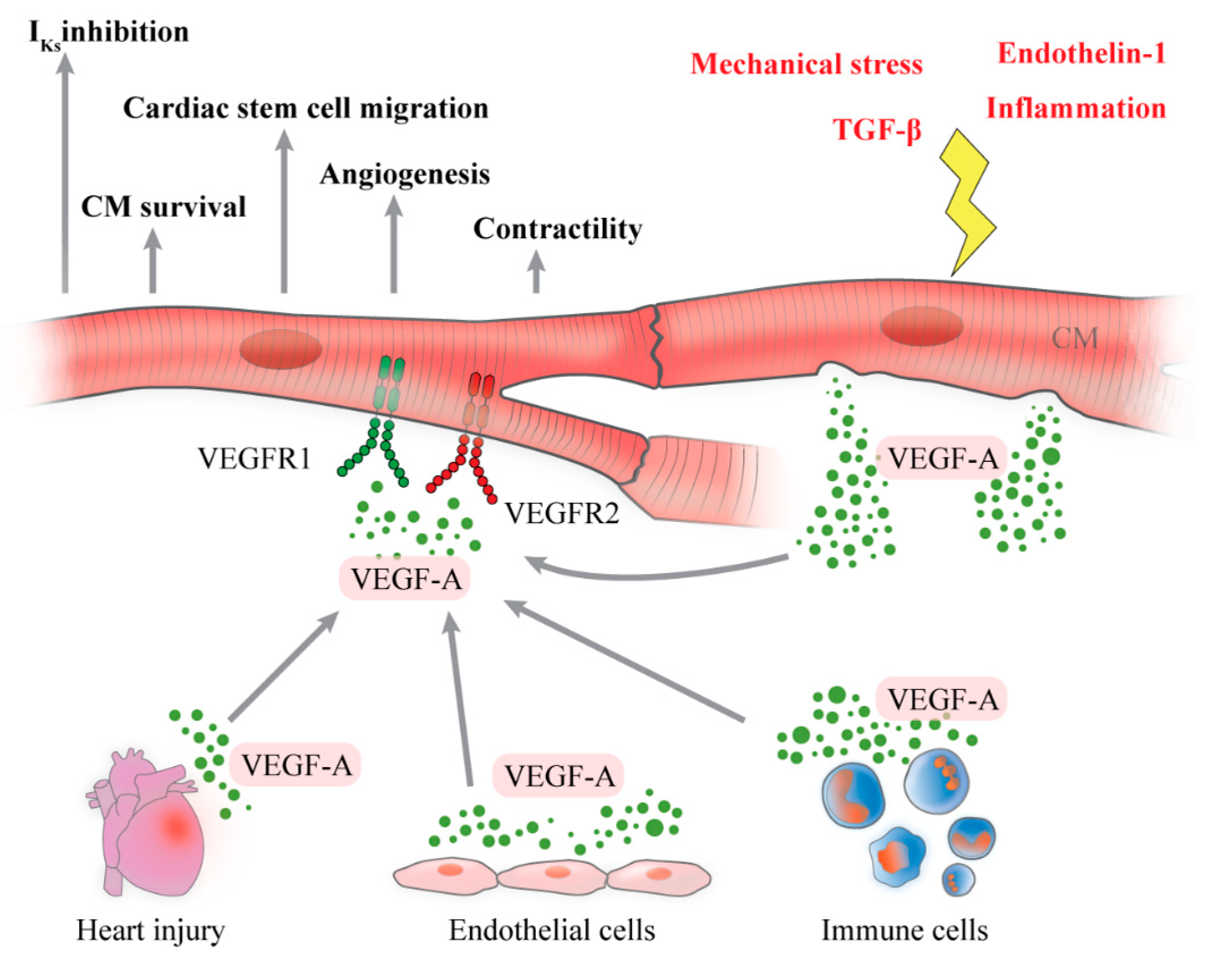

The release of VEGF-A by CM is schematized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of cardiomyocytes (CM) as source and target of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A). A plethora of stimuli including inflammation, mechanical stress, endothelin-1 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) induce CM to produce and release VEGF-A, whose function is to promote angiogenesis in myocardial tissue. CM are also a target of VEGF-A, produced by several cells and during heart injury, through binding with VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, expressed on their surface. CM activation, induced by VEGF-A, enhances CM survival, contractility, cardiac stem cell recruitment, cardiac angiogenesis and reduction of potassium current (IKs).

4. Cardiomyocytes as Target of VEGF-A

CM are both producers and targets of VEGF-A [94,95,96]. This latter exhibits a plethora of actions in reparative wound healing within the myocardium, including vasculogenesis [97], recruitment and homing of stem cells [98], decreased apoptosis [99,100] and increased vasodilatation [101] and modulation of the autonomic response [102]. As previously described, VEGF-A exerts its biological effects by interacting with two main tyrosine kinase receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, with an affinity for VEGFR1 higher than VEGFR2 [97,103]. VEGFR1 and VEGFR2 are both expressed on CM surface, but VEGFR1 is upregulated following hypoxia and oxidative stress [104]. VEGFR1 is also important for cardiac contractility; in fact, the heart uses VEGF-A–phospholipase Cγ1 signaling to control the strength of the heartbeat [105,106]. VEGFR2 is largely expressed on the surviving mouse CM after acute myocardial infarction, and CM viability is significantly improved with VEGF-A164 [107].

It has been demonstrated in the rat model that VEGF-A inhibits CM apoptosis and activates the expression of genes involved in myocardial contractility and metabolism [104,108]. VEGF-A involvement in heart repair also encourages cardiac stem cell migration via the PI3K/Akt pathway [98]. The same research group demonstrates that the pathway VEGF-A together with myocardial stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) encourages cardiac stem cell mobilization and myocardial repair within infarcted heart [109,110].

VEGF-A plays a pivotal role in triggering the cardiac angiogenic response following acute infarcted myocardium [111]. VEGF-A and VEGFR expression is increased at the border zone only in the first day post rat myocardial infarction, but not in the later stages [112], and then it is suppressed during the first week when angiogenesis is more active [113]. Therefore, the withdrawal of VEGF-A may be also related to the later vascular stabilization in the infarcted myocardium [114]. Moreover, VEGF-A reduces potassium current (IKs) through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–mediated molecular pathway, increasing the duration of cardiac action potential in guinea pig ventricular CM. In conclusion, we speculate that VEGF-A, after being released by CM, may have autocrine/paracrine effects activating CM by binding to VEGFRs.

The effects of VEGF-A on CM are shown in Figure 1.

5. VEGF-A and Angiogenesis in Cardiovascular Diseases

As previously stated, angiogenesis is the process of formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels, involving cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, tube formation and regulation of angiogenic factors [115]. It is responsible for a great variety of physiological and pathological processes, including cardiovascular diseases (CVD) [116].

CVD are pathological processes representing the number one cause of mortality in the world [117]. Among them, the most recognized CVD are ischemic disease and atherosclerosis [118,119], which are the most important cause of disability and premature death worldwide [117]. Therefore, CVD seriously affects the quality of life, increasing the psychological and economic burden [117,120].

5.1. Ischemic Heart Disease

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide [121]. World Health Organization reports that 740 million people die of IHD annually all around the world, accounting for the death of 13.2% of the total population [Organization WH. World Health Organization report. May 2014, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/zh/]. Myocardial infarction (MI) is one of the main manifestations of IHD, which induces myocardial necrosis or apoptosis in a short time [122], leading to heart failure with a poor prognosis [123]. It has been classified as the main cause of death in IHD [124]. To date, there are several types of treatments for MI, such as reducing incidence of coronary atherosclerosis [125], antithrombotic therapy including vitamin K antagonists [126], antiplatelet therapy with low-dose aspirin [127] and clopidogrel [128]. In the last years, the therapeutic angiogenesis has been proposed as a new strategy for the treatment of MI. Angiogenesis appears in all vascularized organs [129]. Although ischemia leads to endogenous myocardial angiogenesis, it cannot reach the effect to maintain normal capillary density [130]. Experiments conducted on rat models reveal that serum VEGF-A levels are positively associated with increased microvessel density in the infarcted area, suggesting VEGF-A role in myocardial remodeling and angiogenesis [131,132,133,134,135]. There is compelling evidence that patients with MI have high serum levels of VEGF-A [136]. Moreover, altered levels of VEGF-A are detected also in plasma after MI and are correlated with high inflammation cytokine concentrations [137] suggesting that increased levels of VEGF-A are a part of ongoing inflammatory activity. Since high concentrations of VEGF-A in these patients lead to neovascularization of inflamed plaques and their destabilization, VEGF-A levels are a negative prognostic value [137]. Therefore, therapeutic stimulation of angiogenesis has been regarded as an effective treatment for IHD [138]. Stroke is another main manifestation of IHD. In stroke, the breakdown of the blood–brain barrier leads to the release of reactive oxygen species capable of transforming astrocytes into reactive astrocytes. These reactive astrocytes modify the extracellular matrix (ECM) [139] with a consequent restructuring of the ECM with the formation of ECM traits [140]. EC use these new ECM traits to establish new capillary buds [141]. This mechanism is strictly regulated by a balance between proangiogenic and angiostatic factors [142,143,144,145]. At the onset of ischemia, the combined presence of nitric oxide (NO) and VEGF-A leads to vasodilation and an increase in vascular permeability. This condition generates the extravasation of plasma proteins that promote temporary communication for the migration of EC to ensure vascular germination [146], with subsequent dissociation of smooth muscle cells and the loosening of the ECM. ANGPT2, an inhibitor of Tie2 signaling, and matrix metallopeptidases regulate these mechanisms [117]. After the germination path has been established, the EC proliferate and migrate under VEGF-A signaling, and new blood vessels are maintained by ANGPT1 by activating the Tie2 receptor [147]. To date, understanding the dynamic changes of these angiogenic factors after stroke could be useful for developing effective therapeutic strategies. In this regard, high levels of VEGF-A within hours of a stroke are correlated with angiogenesis in the injured area of the brain. Administration of VEGF-A, after a few minutes of reoxygenation following hypoxic ischemia, exhibits a reduction in brain injury in rats [117].

5.2. Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is an alteration characterized by the accumulation of cholesterol and non-resolving inflammation in the vascular wall of the medium and large arteries [148]. Neovascularization in atherosclerotic damage is essential for plaque growth and instability [149]. In atherosclerosis, VEGF-A performs a dual function [150]. On the one hand, it induces beneficial effects, protecting the EC by increasing the expression levels of anti-apoptotic proteins and NO synthesis [2]. On the other hand, VEGF-A induces harmful effects, acting as mitogen by re-endothelialization [151] and prevention or repair of the endothelial lesion that can induce atherogenesis [152]. In addition, VEGF-A promotes monocyte adhesion, transendothelial migration and activation [153,154], improving also endothelium permeability [1], adhesion protein expression [155] and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 [156]. In human coronaries, VEGF-A and its receptors are not found in normal coronary segments, but their expression increases in EC of microcapillaries, in macrophages and in partially differentiated smooth muscle cells of atherosclerotic lesions [157]. VEGF-A is identified as a marker of atherosclerosis, performing experiments on rabbits [158,159]. Chronic stress reduces atherosclerosis tunica media and induces plaque instability, promoting angiogenesis by release of VEGF-A identified in a great amount in serum [158]. Administration of Resveratrol decreases VEGF-A serum concentration, reducing formation and evolution of atherosclerotic lesions in rabbit model [159]. It has been demonstrated that anti-angiogenic factors reduce atherosclerosis development in various animal models [160]. Therefore, clinical trials with anti-angiogenic drugs such as anti-VEGF/VEGFR, used in anti-cancer therapy, show cardiovascular adverse effects and require additional investigations [161]. Conversely, plasma VEGF-A is weakly associated with cardiovascular risk factors, suggesting circulating VEGF-A has only a little influence on the development of atherosclerosis [162].

As a result of atherosclerosis, there are two other important pathological processes: Atherothrombosis and coronary artery disease.

Atherothrombosis is a complex inflammatory pathological process that involves lipid deposition in the arterial wall with recruitment of circulating leukocytes [163]. This continuous accumulation leads to the growth of a plaque that could become unstable and break, triggering the formation of a thrombus [164]. An occlusive thrombus may possibly be responsible for an ischemic event [165]. In this process, inflammation plays an important role in all phases, especially the reactive protein C, which is one of the main ones responsible for the cascade of events that induces thrombosis [166].

The VEGF-A signaling pathway (VSP) plays an important role in EC, and its inhibition has huge effects on thrombosis [114,167]. Generalized endothelial dysfunction predisposes to both arterial and venous thrombosis [168]. VSP blockade induces vascular toxicity, including arterial thromboembolic events (ATE) [169,170,171]. VSP inhibitors are antibodies, acting directly on VEGF-A, such as bevacizumab [172] and tyrosine kinases inhibitors [173], binding to the kinase domain of VEGF-A receptors, such as sunintib [174] and sorafenib [161]. Age over 65 years, previous thromboembolic events, history of atherosclerotic disease and duration of VSP inhibitor therapy are possible risk factors for ATE during VSP inhibitor therapy [175].

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a pathological process, generally caused by atherosclerosis, in which the coronary arteries are constricted or blocked. The relationship between angiogenesis and CAD is complex. Angiogenesis promotes growth [176] and vulnerability of plaques [177,178], causing intraplaque hemorrhage [179] and the influx of inflammatory cells and erythrocytes [180]. The growth of this accumulation could break the plaque, worsening the pathological condition. In this regard, the blockade of intraplaque angiogenesis is considered as a potential therapeutic target for CAD [160,181,182].

Moreover, patients with CAD have increased serum and plasma levels of VEGF-A [183,184] that correlate with IL-18 concentrations [185], a cytokine that induces VEGF-A expression [183]. This increase may indicate that VEGF-A can be considered as a marker for revascularization when coronary artery injury is critical [186]. Therefore, therapeutic angiogenesis is used to improve the ischemic myocardial reperfusion in patients with CAD and to expand the myocardial microvascular network. To date, there are several therapies. The first one is the administration of angiogenic growth factors directly (protein therapy) [187,188,189]; the second strategy is promoting angiogenic genes expression in vivo (gene therapy) [190,191,192]. Finally, there are other strategies, such as delivering stem cells (cell therapy) [193,194,195,196] or exosomes (cell-free therapy) [143,197,198,199,200].

The effects of VEGF-A in CVD are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Schematic representation of VEGF-A expression in cardiovascular diseases.

6. Conclusions

Angiogenesis is a process responsible for a great variety of physiological and pathological mechanisms, including heart diseases. VEGF-A is the key regulator of angiogenesis. In this review, we discussed present knowledge on the expression and effects on VEGF-A on cardiomyocytes and on the role of VEGF-A in CVD that are the most important cause of disability and premature death worldwide.

CM, the main cell type found in the heart, produce and release VEGF-A and express its receptors, VEGFR1 and VEGFR2, on their cell surface. The lack of VEGF-A expression in CM affects myocardial angiogenesis, resulting in conditions that impair heart functions. Moreover, CM is also a target of VEGF-A because it influences CM biology such as mobilization.

VEGF-A plays an important role in cardiac morphogenesis, cardiac contractility and wound healing within the myocardium. At the same time, high concentrations of VEGF-A are detected in several CVD and are often associated with poor prognosis and disease severity. Further scientific advances have led to the discovery of a broad range of therapeutical targets and novel biomarkers associated with cardiovascular risks. In addition to protein therapy, gene therapy, cell therapy and cell-less therapy, other concepts have been applied to this field with a large amount of energy. As our understanding of pathophisiological mechanisms of CVD becomes more refined, therapeutic angiogenesis is increasingly interesting in the resolution of these pathologies. Based on clinical trials of angiogenesis therapy conducted to date, some of the approaches appear to have modest effects and continue to be investigated, while some of them have affirmed strong evidence of its success.

In this review, we summarized interesting and thought-provoking studies implicating the role of VEGF-A in various cardiovascular diseases. We suggest that with properly designed and conducted clinical trials, it is possible to think that therapeutic angiogenesis could lead to better quality and life span of patients affected by heart diseases.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gjada Criscuolo for critical reading of the review and the administrative staff (Roberto Bifulco and Anna Ferraro), without whom it would not be possible to work as a team.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant affiliation or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, patents received or pending, or royalties.

Abbreviations

| ANGPT | angiopoietin |

| ATE | arterial thromboembolic events |

| CM | cardiomyocytes |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| EC | endothelial cells |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| IL- | interleukin |

| IHD | ischemic heart disease |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| sVEGF-A | soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor β |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth |

| VSP | VEGF-A signaling pathway |

| VEGFR | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

References

- Senger, D.R.; Galli, S.J.; Dvorak, A.M.; Perruzzi, C.A.; Harvey, V.S.; Dvorak, H.F. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science 1983, 219, 983–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Gerber, H.-P.; LeCouter, J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Davis-Smyth, T. The Biology of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Endocr. Rev. 1997, 18, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, S.; Goveia, J.; Stapor, P.C.; Cantelmo, A.R.; Carmeliet, P. The multifaceted activity of VEGF in angiogenesis—Implications for therapy responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varricchi, G.; Loffredo, S.; Galdiero, M.R.; Marone, G.; Cristinziano, L.; Granata, F.; Marone, G. Innate effector cells in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 53, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.E.; Harlow, L.A.; Haines, G.K.; Amento, E.P.; Unemori, E.N.; Wong, W.L.; Pope, R.M.; Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor. A cytokine modulating endothelial function in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 1994, 152, 4149–4156. [Google Scholar]

- Mandriota, S.J.; Seghezzi, G.; Vassalli, J.-D.; Ferrara, N.; Wasi, S.; Mazzieri, R.; Mignatti, P.; Pepper, M.S. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Increases Urokinase Receptor Expression in Vascular Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9709–9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unemori, E.N.; Ferrara, N.; Bauer, E.A.; Amento, E.P. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces interstitial collagenase expression in human endothelial cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1992, 153, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.-J.; Feng, Y.-G.; Lu, W.-P.; Li, H.-T.; Xie, H.-W.; Li, S.-F. Effect of combined VEGF165/ SDF-1 gene therapy on vascular remodeling and blood perfusion in cerebral ischemia. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 127, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, A.S.; Lotfi, S.; Goncharova, E.A.; Tliba, O.; Amrani, Y.; Krymskaya, V.P.; Lazaar, A.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced secretion of fibronectin is ERK dependent. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 286, L539–L545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ruiz, M.; Fulton, D.; Sowa, G.; Languino, L.R.; Fujio, Y.; Walsh, K.; Sessa, W.C. Vascular endothelial growth factor-stimulated actin reorganization and migration of endothelial cells is regulated via the serine/threonine kinase Akt. Circ. Res. 2000, 86, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundkvist, A.; Lee, S.; Iruela-Arispe, L.; Betsholtz, C.; Gerhardt, H. Growth factor gradients in vascular patterning. Novartis Found. Symp. 2007, 283, 194–201; discussion 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Jilani, S.M.; Nikolova, G.V.; Carpizo, D.; Iruela-Arispe, M.L. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J. Cell Biol. 2005, 169, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vempati, P.; Popel, A.S.; Mac Gabhann, F. Extracellular regulation of VEGF: Isoforms, proteolysis, and vascular patterning. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischer, E.; Mitchell, R.; Hartman, T.; Silva, M.; Gospodarowicz, D.; Fiddes, J.C.; Abraham, J.A. The human gene for vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are encoded through alternative exon splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 11947–11954. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, J.P. Unbalanced alternative splicing and its significance in cancer. BioEssays News Rev. Mol. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2006, 28, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi-Nezhad, M. Vascular endothelial growth factor from embryonic status to cardiovascular pathology. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 2, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, N. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor in regulation of physiological angiogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2001, 280, C1358–C1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorenjak, V.; Vance, D.R.; Petrelis, A.M.; Stathopoulou, M.G.; Dadé, S.; El Shamieh, S.; Murray, H.; Masson, C.; Lamont, J.; Fitzgerald, P.; et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells extracts VEGF protein levels and VEGF mRNA: Associations with inflammatory molecules in a healthy population. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, C.J.; Mignone, V.W.; Arruda, M.A.; Alcobia, D.C.; Hill, S.J.; Kilpatrick, L.E.; Woolard, J. Molecular Pharmacology of VEGF-A Isoforms: Binding and Signalling at VEGFR2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, K.A.; Leung, D.W.; Rowland, A.M.; Winer, J.; Ferrara, N. Dual regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor bioavailability by genetic and proteolytic mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 26031–26037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Park, J.E.; Keller, G.A.; Ferrara, N. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) isoforms: Differential deposition into the subepithelial extracellular matrix and bioactivity of extracellular matrix-bound VEGF. Mol. Biol. Cell 1993, 4, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Bao, L.; Zhao, M.; Cao, J.; Zheng, H. Progress in Research on the Role of FGF in the Formation and Treatment of Corneal Neovascularization. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor as a target for anticancer therapy. The Oncologist 2004, 9 (Suppl. 1), 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, S.; Abdellatef, S.; Haddad, M.A.; Fakhoury, I.; El-Sibai, M. Hypoxia and EGF Stimulation Regulate VEGF Expression in Human Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Cells by Differential Regulation of the PI3K/Rho-GTPase and MAPK Pathways. Cells 2019, 8, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saryeddine, L.; Zibara, K.; Kassem, N.; Badran, B.; El-Zein, N. EGF-Induced VEGF Exerts a PI3K-Dependent Positive Feedback on ERK and AKT through VEGFR2 in Hematological In Vitro Models. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seghezzi, G.; Patel, S.; Ren, C.J.; Gualandris, A.; Pintucci, G.; Robbins, E.S.; Shapiro, R.L.; Galloway, A.C.; Rifkin, D.B.; Mignatti, P. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: An autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 141, 1659–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, X.; Wittchen, E.S.; Hartnett, M.E. TNF-α mediates choroidal neovascularization by upregulating VEGF expression in RPE through ROS-dependent β-catenin activation. Mol. Vis. 2016, 22, 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhrberg, C.; Gerhardt, H.; Golding, M.; Watson, R.; Ioannidou, S.; Fujisawa, H.; Betsholtz, C.; Shima, D.T. Spatially restricted patterning cues provided by heparin-binding VEGF-A control blood vessel branching morphogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2684–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmans, I.; Ng, Y.-S.; Rohan, R.; Fruttiger, M.; Bouché, A.; Yuce, A.; Fujisawa, H.; Hermans, B.; Shani, M.; Jansen, S.; et al. Arteriolar and venular patterning in retinas of mice selectively expressing VEGF isoforms. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 109, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, S.; Tugues, S.; Li, X.; Gualandi, L.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signal transduction by vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Biochem. J. 2011, 437, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, G.A.; Fearnley, G.W.; Tomlinson, D.C.; Harrison, M.A.; Ponnambalam, S. The cellular response to vascular endothelial growth factors requires co-ordinated signal transduction, trafficking and proteolysis. Biosci. Rep. 2015, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.P.; Fabbro, D.; Kelly, E.; Marrion, N.; Peters, J.A.; Benson, H.E.; Faccenda, E.; Pawson, A.J.; Sharman, J.L.; Southan, C.; et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: Catalytic receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 5979–6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detoraki, A.; Staiano, R.I.; Granata, F.; Giannattasio, G.; Prevete, N.; de Paulis, A.; Ribatti, D.; Genovese, A.; Triggiani, M.; Marone, G. Vascular endothelial growth factors synthesized by human lung mast cells exert angiogenic effects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 123, 1142–1149.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, A.; Murray, J.; Saito, Y.; Kanthou, C.; Benzakour, O.; Shibuya, M.; Wijelath, E.S. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors in smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2001, 188, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabrun, N.; Bühring, H.J.; Choi, K.; Ullrich, A.; Risau, W.; Keller, G. Flk-1 expression defines a population of early embryonic hematopoietic precursors. Dev. Camb. Engl. 1997, 124, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, A.N.; Dai, J.; Weich, H.A.; Vrensen, G.F.J.M.; Schlingemann, R.O. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1, 2, and 3 in quiescent endothelia. J. Histochem. Cytochem. Off. J. Histochem. Soc. 2002, 50, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.D.; Mohammadi, M.; Rahimi, N. A single amino acid substitution in the activation loop defines the decoy characteristic of VEGFR-1/FLT-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, B.I.; Dougher-Vermazen, M.; Carrion, M.E.; Dimitrov, D.; Armellino, D.C.; Gospodarowicz, D.; Böhlen, P. Identification of the KDR tyrosine kinase as a receptor for vascular endothelial cell growth factor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992, 187, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, C.; Escobedo, J.A.; Ueno, H.; Houck, K.; Ferrara, N.; Williams, L.T. The fms-like tyrosine kinase, a receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Science 1992, 255, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltenberger, J.; Claesson-Welsh, L.; Siegbahn, A.; Shibuya, M.; Heldin, C.H. Different signal transduction properties of KDR and Flt1, two receptors for vascular endothelial growth factor. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 26988–26995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hornig, C.; Weich, H.A. Soluble VEGF receptors. Angiogenesis 1999, 3, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, M.; Claesson-Welsh, L. Signal transduction by VEGF receptors in regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, E.A.; Matkovich, S.J. Cardiomyocytes structure, function and associated pathologies. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 1746–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.J.S.; Ang, Y.-S.; Fu, J.-D.; Rivas, R.N.; Mohamed, T.M.A.; Higgs, G.C.; Srivastava, D.; Pruitt, B.L. Contractility of single cardiomyocytes differentiated from pluripotent stem cells depends on physiological shape and substrate stiffness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12705–12710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittman, R.N. Regulation of Tissue Oxygenation; Integrated Systems Physiology: From Molecule to Function to Disease; Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, C.A.; Spinale, F.G. The structure and function of the cardiac myocyte: A review of fundamental concepts. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1999, 118, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.S.; Langer, G.A.; Nudd, L.M.; Seraydarian, K. The myocardial cell surface, its histochemistry, and the effect of sialic acid and calcium removal on its stucture and cellular ionic exchange. Circ. Res. 1977, 41, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, J.S.; Langer, G.A. The myocardial interstitium: Its structure and its role in ionic exchange. J. Cell Biol. 1974, 60, 586–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Borg, T.K.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z.; Gao, B.Z. Role of the Basement Membrane in Regulation of Cardiac Electrical Properties. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2014, 42, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, G.A.; Frank, J.S.; Rich, T.L.; Orner, F.B. Calcium exchange, structure, and function in cultured adult myocardial cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1987, 252, H314–H324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langer, G.A.; Frank, J.S.; Philipson, K.D. Ultrastructure and calcium exchange of the sarcolemma, sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria of the myocardium. Pharmacol. Ther. 1982, 16, 331–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Shaw, R.M. Cardiac T-Tubule Microanatomy and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, G.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, H.M.; Yang, D. Intercalated discs: Cellular adhesion and signaling in heart health and diseases. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCain, M.L.; Parker, K.K. Mechanotransduction: The role of mechanical stress, myocyte shape, and cytoskeletal architecture on cardiac function. Pflüg. Arch.- Eur. J. Physiol. 2011, 462, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhathakurta, P.; Prochniewicz, E.; Thomas, D.D. Actin-Myosin Interaction: Structure, Function and Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.D.; Yuan, C.-C.; McCabe, K.J.; Murray, J.D.; Childers, M.C.; Flint, G.V.; Moussavi-Harami, F.; Mohran, S.; Castillo, R.; Zuzek, C.; et al. Cardiac myosin activation with 2-deoxy-ATP via increased electrostatic interactions with actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11502–11507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Namba, K.; Fujii, T. Cardiac muscle thin filament structures reveal calcium regulatory mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.V.; Javadov, S.; Grimm, M.; Margreiter, R.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Hagenbuchner, J. Crosstalk between Mitochondria and Cytoskeleton in Cardiac Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohjoismäki, J.L.; Goffart, S. The role of mitochondria in cardiac development and protection. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 106, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarewicz, J.; Manly, A.; Kokoszka, S.; Sleiman, N.; Leff, T.; Cala, S. Adiponectin secretion from cardiomyocytes produces canonical multimers and partial co-localization with calsequestrin in junctional SR. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 457, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frangogiannis, N.G. The Reparative Function of Cardiomyocytes in the Infarcted Myocardium. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 797–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada, D.; Specker, G.; Martínez, A.; Dias, P.P.; Hissa, B.; Andrade, L.O.; Radi, R.; Piacenza, L. Cardiomyocyte diffusible redox mediators control Trypanosoma cruzi infection: Role of parasite mitochondrial iron superoxide dismutase. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 1235–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Wu, Z.; Rao, L.; Li, Y. Metabolites of Hypoxic Cardiomyocytes Induce the Migration of Cardiac Fibroblasts. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 41, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancey, C.; Corbi, P.; Froger, J.; Delwail, A.; Wijdenes, J.; Gascan, H.; Potreau, D.; Lecron, J.-C. Secretion of IL-6, IL-11 and lif by human cardiomyocytes in primary culture. Cytokine 2002, 18, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoyagi, T.; Matsui, T. The Cardiomyocyte as a Source of Cytokines in Cardiac Injury. J. Cell Sci. Ther. 2011, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.C.H.; Davis, M.E.; Lisowski, L.K.; Lee, R.T. Endothelial-cardiomyocyte interactions in cardiac development and repair. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006, 68, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, T.; Horstkotte, J.; Schwab, C.; Pfetsch, V.; Weinmann, K.; Dietzel, S.; Rohwedder, I.; Hinkel, R.; Gross, L.; Lee, S.; et al. Angiopoietin 2 mediates microvascular and hemodynamic alterations in sepsis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, M.; Kakinuma, Y.; Ando, M.; Katare, R.G.; Yamasaki, F.; Doi, Y.; Sato, T. Nitric Oxide Stimulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Production in Cardiomyocytes Involved in Angiogenesis. J. Physiol. Sci. 2006, 56, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhinand, C.S.; Raju, R.; Soumya, S.J.; Arya, P.S.; Sudhakaran, P.R. VEGF-A/VEGFR2 signaling network in endothelial cells relevant to angiogenesis. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2016, 10, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, F.J.; Gerber, H.P.; Williams, S.P.; VanBruggen, N.; Bunting, S.; Ruiz-Lozano, P.; Gu, Y.; Nath, A.K.; Huang, Y.; Hickey, R.; et al. A cardiac myocyte vascular endothelial growth factor paracrine pathway is required to maintain cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 5780–5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, N.; Dubé, K.N.; Riley, P.R. Coronary vessel development and insight towards neovascular therapy. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2009, 90, 262–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P.; Ng, Y.S.; Nuyens, D.; Theilmeier, G.; Brusselmans, K.; Cornelissen, I.; Ehler, E.; Kakkar, V.V.; Stalmans, I.; Mattot, V.; et al. Impaired myocardial angiogenesis and ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dor, Y.; Camenisch, T.D.; Itin, A.; Fishman, G.I.; McDonald, J.A.; Carmeliet, P.; Keshet, E. A novel role for VEGF in endocardial cushion formation and its potential contribution to congenital heart defects. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2001, 128, 1531–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Dor, Y.; Klewer, S.E.; McDonald, J.A.; Keshet, E.; Camenisch, T.D. VEGF modulates early heart valve formation. Anat. Rec. A. Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 2003, 271, 202–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miquerol, L.; Langille, B.L.; Nagy, A. Embryonic development is disrupted by modest increases in vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression. Dev. Camb. Engl. 2000, 127, 3941–3946. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrechts, D.; Carmeliet, P. Sculpting heart valves with NFATc and VEGF. Cell 2004, 118, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chang, C.-P.; Neilson, J.R.; Bayle, J.H.; Gestwicki, J.E.; Kuo, A.; Stankunas, K.; Graef, I.A.; Crabtree, G.R. A field of myocardial-endocardial NFAT signaling underlies heart valve morphogenesis. Cell 2004, 118, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seko, Y.; Seko, Y.; Takahashi, N.; Shibuya, M.; Yazaki, Y. Pulsatile stretch stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion by cultured rat cardiac myocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 254, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and cardiovascular disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014, 76, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Xie, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Jia, L.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Ma, H.; Xiang, M. Increased myocardial stiffness activates cardiac microvascular endothelial cell via VEGF paracrine signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, A.; Hou, R.; Zhang, J.; Jia, X.; Jiang, W.; Chen, J. Salidroside protects cardiomyocyte against hypoxia-induced death: A HIF-1α-activated and VEGF-mediated pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 607, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leychenko, A.; Konorev, E.; Jijiwa, M.; Matter, M.L. Stretch-induced hypertrophy activates NFkB-mediated VEGF secretion in adult cardiomyocytes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e29055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Hampton, T.; Morgan, J.P.; Simons, M. Stretch-induced VEGF expression in the heart. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 100, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimojo, N.; Jesmin, S.; Zaedi, S.; Otsuki, T.; Maeda, S.; Yamaguchi, N.; Aonuma, K.; Hattori, Y.; Miyauchi, T. Contributory role of VEGF overexpression in endothelin-1-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H474–H481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rysä, J.; Tenhunen, O.; Serpi, R.; Soini, Y.; Nemer, M.; Leskinen, H.; Ruskoaho, H. GATA-4 is an angiogenic survival factor of the infarcted heart. Circ. Heart Fail. 2010, 3, 440–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, J.; Auger-Messier, M.; Xu, J.; Oka, T.; Sargent, M.A.; York, A.; Klevitsky, R.; Vaikunth, S.; Duncan, S.A.; Aronow, B.J.; et al. Cardiomyocyte GATA4 functions as a stress-responsive regulator of angiogenesis in the murine heart. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3198–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berlo, J.H.; Elrod, J.W.; van den Hoogenhof, M.M.G.; York, A.J.; Aronow, B.J.; Duncan, S.A.; Molkentin, J.D. The transcription factor GATA-6 regulates pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2010, 107, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.S.; Kim, Y.; Joung, H.; Kwon, D.-H.; Choe, N.; Min, H.-K.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, D.-K.; Cho, Y.K.; et al. Small heterodimer partner blocks cardiac hypertrophy by interfering with GATA6 signaling. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Berlo, J.H.; Aronow, B.J.; Molkentin, J.D. Parsing the roles of the transcription factors GATA-4 and GATA-6 in the adult cardiac hypertrophic response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, J.M.; Eubank, T.D.; Roberts, R.D.; Wang, Y.; Pore, N.; Maity, A.; Marsh, C.B. M-CSF signals through the MAPK/ERK pathway via Sp1 to induce VEGF production and induces angiogenesis in vivo. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-H.; Lai, S.-C.; Chau, L.-Y. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide induces vascular endothelial growth factor expression via p38 kinase-dependent activation of Sp1. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 3829–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, B.A.; Yokota, T.; Chintalgattu, V.; Ren, S.; Iruela-Arispe, L.; Khakoo, A.Y.; Minamisawa, S.; Wang, Y. Cardiac myocyte p38α kinase regulates angiogenesis via myocyte-endothelial cell cross-talk during stress-induced remodeling in the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12787–12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Amende, I.; Hampton, T.G.; Yang, Y.; Ke, Q.; Min, J.-Y.; Xiao, Y.-F.; Morgan, J.P. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes cardiomyocyte differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H1653–H1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, G.; Cohen, T.; Gengrinovitch, S.; Poltorak, Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1999, 13, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlman, J.D.; Hibberd, M.G.; Chuang, M.L.; Harada, K.; Lopez, J.J.; Gladstone, S.R.; Friedman, M.; Sellke, F.W.; Simons, M. Magnetic resonance mapping demonstrates benefits of VEGF-induced myocardial angiogenesis. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taimeh, Z.; Loughran, J.; Birks, E.J.; Bolli, R. Vascular endothelial growth factor in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2013, 10, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, J.; Kong, X.; Yang, J.; Guo, L.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Y.; Wan, Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes cardiac stem cell migration via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 3521–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friehs, I.; Barillas, R.; Vasilyev, N.V.; Roy, N.; McGowan, F.X.; del Nido, P.J. Vascular endothelial growth factor prevents apoptosis and preserves contractile function in hypertrophied infant heart. Circulation 2006, 114, I290–I295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Chen, B.; Tan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhu, T.; Cao, K.; Yang, Z.; Kan, Y.W.; Su, H. Coexpression of VEGF and angiopoietin-1 promotes angiogenesis and cardiomyocyte proliferation reduces apoptosis in porcine myocardial infarction (MI) heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2064–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, E. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001, 49, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgers, M.; Voipio-Pulkki, L.-M.; Izumo, S. Apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 45, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madonna, R.; De Caterina, R. VEGF receptor switching in heart development and disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 84, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentilin, L.; Puligadda, U.; Lionetti, V.; Zacchigna, S.; Collesi, C.; Pattarini, L.; Ruozi, G.; Camporesi, S.; Sinagra, G.; Pepe, M.; et al. Cardiomyocyte VEGFR-1 activation by VEGF-B induces compensatory hypertrophy and preserves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Cui, G.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, J.; Shao, S. Sustained delivery of VEGF from designer self-assembling peptides improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 424, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottbauer, W. VEGF-PLC 1 pathway controls cardiac contractility in the embryonic heart. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 1624–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsic, N.; Zentilin, L.; Zacchigna, S.; Santoro, D.; Stanta, G.; Salvi, A.; Sinagra, G.; Giacca, M. Induction of functional neovascularization by combined VEGF and angiopoietin-1 gene transfer using AAV vectors. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2003, 7, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poltorak, Z.; Cohen, T.; Neufeld, G. The VEGF splice variants: Properties, receptors, and usage for the treatment of ischemic diseases. Herz 2000, 25, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Dewald, O.; Frangogiannis, N. Inflammatory Mechanisms in Myocardial Infarction. Curr. Drug Target -Inflamm. Allergy 2003, 2, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.-M.; Wang, J.-N.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, F.; Yang, J.-Y.; Kong, X.; Guo, L.-Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Wan, Y.; et al. VEGF/SDF-1 promotes cardiac stem cell mobilization and myocardial repair in the infarcted heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 91, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Ahokas, R.A.; Sun, Y. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms and receptor subtypes in the infarcted heart. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 167, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Brown, L.F.; Hibberd, M.G.; Grossman, J.D.; Morgan, J.P.; Simons, M. VEGF, flk-1, and flt-1 expression in a rat myocardial infarction model of angiogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 270, H1803–H1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Ahokas, R.A.; Sun, Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A: Role on cardiac angiogenesis following myocardial infarction. Microvasc. Res. 2010, 80, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, R.M.; Herrmann, J. Cardiotoxicity with vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor therapy. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucuzian, A.A.; Gassman, A.A.; East, A.T.; Greisler, H.P. Molecular mediators of angiogenesis. J. Burn Care Res. Off. Publ. Am. Burn Assoc. 2010, 31, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeliet, P.; Jain, R.K. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 2000, 407, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.-M.; Verfaillie, C.; Yu, H. Vascular Diseases and Metabolic Disorders. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 5810358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.; Forouzanfar, M.; Sampson, U.; Chugh, S.; Feigin, V.; Mensah, G. The epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors 2010 Study. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 56, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Benjamin, E.J.; Go, A.S.; Arnett, D.K.; Blaha, M.J.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; de Ferranti, S.; Després, J.-P.; Fullerton, H.J.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016, 133, e38-360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenkovich, C.F. We Know More Than We Can Tell About Diabetes and Vascular Disease: The 2016 Edwin Bierman Award Lecture. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, M.S. Advancing cardiovascular research. Chest 2012, 141, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Long, H.; Xu, B. Reduced apoptosis after acute myocardial infarction by simvastatin. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 71, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.; Teng, T.-H.K.; Finn, J.; Knuiman, M.; Briffa, T.; Stewart, S.; Sanfilippo, F.M.; Ridout, S.; Hobbs, M. Trends from 1996 to 2007 in incidence and mortality outcomes of heart failure after acute myocardial infarction: A population-based study of 20,812 patients with first acute myocardial infarction in Western Australia. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2013, 2, e000172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, S.; Thygesen, K.; Kuulasmaa, K.; Giampaoli, S.; Mähönen, M.; Ngu Blackett, K.; Lisheng, L. Writing group on behalf of the participating experts of the WHO consultation for revision of WHO definition of myocardial infarction World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction: 2008-09 revision. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 40, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalen, J.E.; Alpert, J.S.; Goldberg, R.J.; Weinstein, R.S. The epidemic of the 20(th) century: Coronary heart disease. Am. J. Med. 2014, 127, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, N.R.; Patel, D.V.; Murumkar, P.R.; Yadav, M.R. Contemporary developments in the discovery of selective factor Xa inhibitors: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 671–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Collins, R.; Emberson, J.; Godwin, J.; Peto, R.; Buring, J.; Hennekens, C.; Kearney, P.; et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: Collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2009, 373, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.R.; Ju, C.; Zettler, M.; Messenger, J.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Stone, G.W.; Baker, B.A.; Effron, M.; Peterson, E.D.; Wang, T.Y. Outcomes of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Receiving an Oral Anticoagulant and Dual Antiplatelet Therapy: A Comparison of Clopidogrel Versus Prasugrel From the TRANSLATE-ACS Study. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015, 8, 1880–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, A.; Tvorogov, D.; Alitalo, A.; Leppänen, V.-M.; An, Y.; Han, E.C.; Orsenigo, F.; Gaál, E.I.; Holopainen, T.; Koh, Y.J.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-angiopoietin chimera with improved properties for therapeutic angiogenesis. Circulation 2013, 127, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht-Schgoer, K.; Schgoer, W.; Holfeld, J.; Theurl, M.; Wiedemann, D.; Steger, C.; Gupta, R.; Semsroth, S.; Fischer-Colbrie, R.; Beer, A.G.E.; et al. The angiogenic factor secretoneurin induces coronary angiogenesis in a model of myocardial infarction by stimulation of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in endothelial cells. Circulation 2012, 126, 2491–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.-G.; Bi, M.-H.; Wu, P.-S. Study on the expression of VEGF and HIF-1α in infarct area of rats with AMI. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2016, 20, 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Seko, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Nagai, R. Serum levels of endostatin, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing early reperfusion therapy. Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979 2004, 106, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wan, J.; Pan, W.; Zou, J. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in cardiac repair: Signaling mechanisms mediating vascular protective effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Lu, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zeng, S.; Zhan, Q.; Yuan, M.; Yang, Q.; Xia, J. Correlation of Plasma Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Endostatin Levels with Symptomatic Intra- and Extracranial Atherosclerotic Stenosis in a Chinese Han Population. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 2017, 26, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-M.; Zhang, X.-B.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H.-D.; Zhang, Y.-N. Astragalosides promote angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in a rat model of myocardial infarction. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 6718–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinohara, K. The expression and the role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in human normal and myocardial infarcted heart. Hokkaido Igaku Zasshi 1994, 69, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eržen, B.; Šilar, M.; Šabovič, M. Stable phase post-MI patients have elevated VEGF levels correlated with inflammation markers, but not with atherosclerotic burden. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2014, 14, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banquet, S.; Gomez, E.; Nicol, L.; Edwards-Lévy, F.; Henry, J.-P.; Cao, R.; Schapman, D.; Dautreaux, B.; Lallemand, F.; Bauer, F.; et al. Arteriogenic therapy by intramyocardial sustained delivery of a novel growth factor combination prevents chronic heart failure. Circulation 2011, 124, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iadecola, C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron 2013, 80, 844–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Zoppo, G.J.; Mabuchi, T. Cerebral microvessel responses to focal ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003, 23, 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, G.-Y. Therapeutic angiogenesis for brain ischemia: A brief review. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. Off. J. Soc. NeuroImmune Pharmacol. 2007, 2, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.; Plate, K.H. Angiogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 2009, 117, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.-S.; Cheng, K.; Malliaras, K.; Smith, R.R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B.; Matsushita, N.; Blusztajn, A.; Terrovitis, J.; Kusuoka, H.; et al. Direct comparison of different stem cell types and subpopulations reveals superior paracrine potency and myocardial repair efficacy with cardiosphere-derived cells. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talwar, T.; Srivastava, M.V.P. Role of vascular endothelial growth factor and other growth factors in post-stroke recovery. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2014, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.-Q.; Wang, S.; Kim, H.-Y.; Storrie, H.; Rosen, B.R.; Mooney, D.J.; Wang, X.; Lo, E.H. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeliet, P.; Collen, D. Molecular basis of angiogenesis. Role of VEGF and VE-cadherin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 902, 249–262; discussion 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutsenko, S.V.; Kiselev, S.M.; Severin, S.E. Molecular mechanisms of tumor angiogenesis. Biochem. Biokhimiia 2003, 68, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobiyama, K.; Ley, K. Atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 1118–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Role of lipids and intraplaque hypoxia in the formation of neovascularization in atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, P.W.; Slart, R.H.J.A.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Tio, R.A. Atherosclerotic plaque development and instability: A dual role for VEGF. Ann. Med. 2009, 41, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahara, T.; Chen, D.; Tsurumi, Y.; Kearney, M.; Rossow, S.; Passeri, J.; Symes, J.F.; Isner, J.M. Accelerated restitution of endothelial integrity and endothelium-dependent function after phVEGF165 gene transfer. Circulation 1996, 94, 3291–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaré, C.; Pucelle, M.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Angiogenesis in the atherosclerotic plaque. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barleon, B.; Sozzani, S.; Zhou, D.; Weich, H.A.; Mantovani, A.; Marmé, D. Migration of human monocytes in response to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is mediated via the VEGF receptor flt-1. Blood 1996, 87, 3336–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaipersad, A.S.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Silverman, S.; Shantsila, E. The Role of Monocytes in Angiogenesis and Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Moon, S.O.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Koh, Y.S.; Koh, G.Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin through nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 7614–7620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.H.; Ryu, J.; Han, K.H. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1–induced angiogenesis is mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor-A. Blood 2005, 105, 1405–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylä-Herttuala, S.; Rissanen, T.T.; Vajanto, I.; Hartikainen, J. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.-M.; Deng, X.-T.; Qi, R.-M.; Xiao, L.-Y.; Yang, C.-Q.; Gong, T. Mechanism of Chronic Stress-induced Reduced Atherosclerotic Medial Area and Increased Plaque Instability in Rabbit Models of Chronic Stress. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.) 2018, 131, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, L.; González, J.C. Effect of resveratrol on seric vascular endothelial growth factor concentrations during atherosclerosis. Clin. E Investig. En Arterioscler. Publicacion Soc. Espanola Arterioscler. 2018, 30, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, K.S.; Heller, E.; Konerding, M.A.; Flynn, E.; Palinski, W.; Folkman, J. Angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin or TNP-470 reduce intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 1999, 99, 1726–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choueiri, T.K.; Schutz, F.A.B.; Je, Y.; Rosenberg, J.E.; Bellmunt, J. Risk of arterial thromboembolic events with sunitinib and sorafenib: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 28, 2280–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandhofer, A.; Tatarczyk, T.; Kirchmair, R.; Iglseder, B.; Paulweber, B.; Patsch, J.R.; Schratzberger, P. Are plasma VEGF and its soluble receptor sFlt-1 atherogenic risk factors? Cross-sectional data from the SAPHIR study. Atherosclerosis 2009, 206, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Loscalzo, J.; Ridker, P.M.; Farkouh, M.E.; Hsue, P.Y.; Fuster, V.; Hasan, A.A.; Amar, S. Inflammation, Immunity, and Infection in Atherothrombosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döring, Y.; Soehnlein, O.; Weber, C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Atherosclerosis and Atherothrombosis. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 736–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badimon, L.; Suades, R.; Crespo, J.; Padro, T.; Chiva-Blanch, G. Diet, microparticles and atherothrombosis. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2018, 23, 432–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigo, K.; Inforzato, A.; Barajon, I.; Garlanda, C.; Bottazzi, B.; Meri, S.; Mantovani, A. Pentraxins in the activation and regulation of innate immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 274, 202–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrillaga-Romany, I.; Norden, A.D. Antiangiogenic therapies for glioblastoma. CNS Oncol. 2014, 3, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puranik, R.; Celermajer, D.S. Smoking and endothelial function. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2003, 45, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooney, M.M.; Tserng, K.-Y.; Makar, V.; McPeak, R.J.; Ingalls, S.T.; Dowlati, A.; Overmoyer, B.; McCrae, K.; Ksenich, P.; Lavertu, P.; et al. A phase IB clinical and pharmacokinetic study of the angiogenesis inhibitor SU5416 and paclitaxel in recurrent or metastatic carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2005, 55, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppelt, P.; Betbadal, A.; Nayak, L. Approach to chemotherapy-associated thrombosis. Vasc. Med. Lond. Engl. 2015, 20, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangari, M.; Fink, L.M.; Elice, F.; Zhan, F.; Adcock, D.M.; Tricot, G.J. Thrombotic events in patients with cancer receiving antiangiogenesis agents. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 4865–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, O.; Coriat, R.; Cabanes, L.; Ropert, S.; Billemont, B.; Alexandre, J.; Durand, J.-P.; Treluyer, J.-M.; Knebelmann, B.; Goldwasser, F. An observational study of bevacizumab-induced hypertension as a clinical biomarker of antitumor activity. Oncologist 2011, 16, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semeniuk-Wojtaś, A.; Lubas, A.; Stec, R.; Szczylik, C.; Niemczyk, S. Influence of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors on Hypertension and Nephrotoxicity in Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rini, B.I.; Cohen, D.P.; Lu, D.R.; Chen, I.; Hariharan, S.; Gore, M.E.; Figlin, R.A.; Baum, M.S.; Motzer, R.J. Hypertension as a biomarker of efficacy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, R.M.; Herrmann, S.M.S.; Herrmann, J. Vascular toxicities with VEGF inhibitor therapies-focus on hypertension and arterial thrombotic events. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2018, 12, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hinsbergh, V.W.M.; Eringa, E.C.; Daemen, M.J.A.P. Neovascularization of the atherosclerotic plaque: Interplay between atherosclerotic lesion, adventitia-derived microvessels and perivascular fat. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2015, 26, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarczyk, K.; Sattler, K.J.E.; Galili, O.; Versari, D.; Olson, M.L.; Meyer, F.B.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Placenta growth factor expression in human atherosclerotic carotid plaques is related to plaque destabilization. Atherosclerosis 2008, 196, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluimer, J.C.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Bijnens, A.P.J.J.; Maxfield, K.; Pacheco, E.; Kutys, B.; Duimel, H.; Frederik, P.M.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.M.; Virmani, R.; et al. Thin-walled microvessels in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques show incomplete endothelial junctions relevance of compromised structural integrity for intraplaque microvascular leakage. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.-B.; Virmani, R.; Arbustini, E.; Pasterkamp, G. Intraplaque haemorrhages as the trigger of plaque vulnerability. Eur. Heart J. 2011, 32, 1977–1985, 1985a, 1985b, 1985c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziakas, D.N.; Kaski, J.C.; Chalikias, G.K.; Romero, C.; Fredericks, S.; Tentes, I.K.; Kortsaris, A.X.; Hatseras, D.I.; Holt, D.W. Total cholesterol content of erythrocyte membranes is increased in patients with acute coronary syndrome: A new marker of clinical instability? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 2081–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, K.S.; Vakili, K.; Zurakowski, D.; Soliman, M.; Butterfield, C.; Sylvin, E.; Lo, K.-M.; Gillies, S.; Javaherian, K.; Folkman, J. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4736–4741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnik, S.; Lohmann, C.; Siciliani, G.; von Lukowicz, T.; Kuschnerus, K.; Kraenkel, N.; Brokopp, C.E.; Enseleit, F.; Michels, S.; Ruschitzka, F.; et al. Systemic VEGF inhibition accelerates experimental atherosclerosis and disrupts endothelial homeostasis--implications for cardiovascular safety. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 2453–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.-L.; Jung, Y.O.; Moon, Y.-M.; Min, S.-Y.; Yoon, C.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Cho, C.-S.; Jue, D.-M.; Kim, H.-Y. Interleukin-18 induces the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts via AP-1-dependent pathways. Immunol. Lett. 2006, 103, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, R.; Pei, Z.; Chen, B.; Ma, R.; Zhang, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, A.; Wu, T.; Liu, D.; Dong, Y. Age-related change of serum angiogenic factor levels in patients with coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol. 2009, 64, 735–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vm, M.; Al, S.; Aa, A.; As, Z.; Av, K.; Rs, O.; Im, M.; Ga, K. Circulating interleukin-18: Association with IL-8, IL-10 and VEGF serum levels in patients with and without heart rhythm disorders. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 215, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kucukardali, Y.; Aydogdu, S.; Ozmen, N.; Yonem, A.; Solmazgul, E.; Ozyurt, M.; Cingozbay, Y.; Aydogdu, A. The relationship between severity of coronary artery disease and plasma level of vascular endothelial growth factor. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2008, 9, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, R.J. Therapeutic angiogenesis: Angiogenic growth factors for ischemic heart disease. Future Cardiol. 2016, 12, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laham, R.J.; Chronos, N.A.; Pike, M.; Leimbach, M.E.; Udelson, J.E.; Pearlman, J.D.; Pettigrew, R.I.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Yoshizawa, C.; Simons, M. Intracoronary basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2) in patients with severe ischemic heart disease: Results of a phase I open-label dose escalation study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 2132–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsos, S.; Katsanos, K.; Koletsis, E.; Kagadis, G.C.; Anastasiou, N.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Karnabatidis, D.; Dougenis, D. Therapeutic angiogenesis for myocardial ischemia revisited: Basic biological concepts and focus on latest clinical trials. Angiogenesis 2012, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grines, C.L.; Watkins, M.W.; Helmer, G.; Penny, W.; Brinker, J.; Marmur, J.D.; West, A.; Rade, J.J.; Marrott, P.; Hammond, H.K.; et al. Angiogenic Gene Therapy (AGENT) trial in patients with stable angina pectoris. Circulation 2002, 105, 1291–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grines, C.L.; Watkins, M.W.; Mahmarian, J.J.; Iskandrian, A.E.; Rade, J.J.; Marrott, P.; Pratt, C.; Kleiman, N. Angiogene GENe Therapy (AGENT-2) Study Group A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Ad5FGF-4 gene therapy and its effect on myocardial perfusion in patients with stable angina. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 42, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, T.D.; Grines, C.L.; Watkins, M.W.; Dib, N.; Barbeau, G.; Moreadith, R.; Andrasfay, T.; Engler, R.L. Effects of Ad5FGF-4 in patients with angina: An analysis of pooled data from the AGENT-3 and AGENT-4 trials. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afzal, M.R.; Samanta, A.; Shah, Z.I.; Jeevanantham, V.; Abdel-Latif, A.; Zuba-Surma, E.K.; Dawn, B. Adult Bone Marrow Cell Therapy for Ischemic Heart Disease: Evidence and Insights From Randomized Controlled Trials. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelman, S.; Liu, P.P.; Mann, D.L. Role of innate and adaptive immune mechanisms in cardiac injury and repair. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattler, S.; Rosenthal, N. The neonate versus adult mammalian immune system in cardiac repair and regeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1863, 1813–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, B.A.; Natsumeda, M.; Balkan, W.; Hare, J.M. What Is the Future of Cell-Based Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran, J.M.; Makarewich, C.A.; Sharp, T.E.; Starosta, T.; Zhu, F.; Hoffman, N.E.; Chiba, Y.; Madesh, M.; Berretta, R.M.; Kubo, H.; et al. Bone-derived stem cells repair the heart after myocardial infarction through transdifferentiation and paracrine signaling mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2013, 113, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.D.; French, K.M.; Ghosh-Choudhary, S.; Maxwell, J.T.; Brown, M.E.; Platt, M.O.; Searles, C.D.; Davis, M.E. Identification of therapeutic covariant microRNA clusters in hypoxia-treated cardiac progenitor cell exosomes using systems biology. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Losordo, D.W. Exosomes and cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicencio, J.M.; Yellon, D.M.; Sivaraman, V.; Das, D.; Boi-Doku, C.; Arjun, S.; Zheng, Y.; Riquelme, J.A.; Kearney, J.; Sharma, V.; et al. Plasma exosomes protect the myocardium from ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).