Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance

Abstract

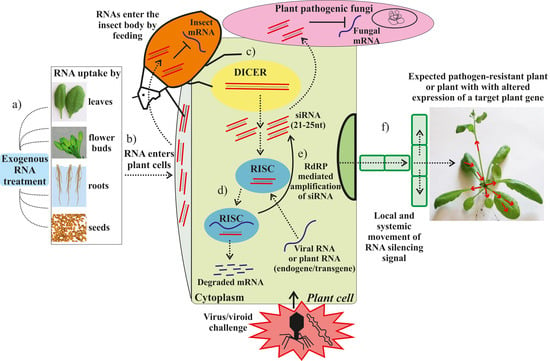

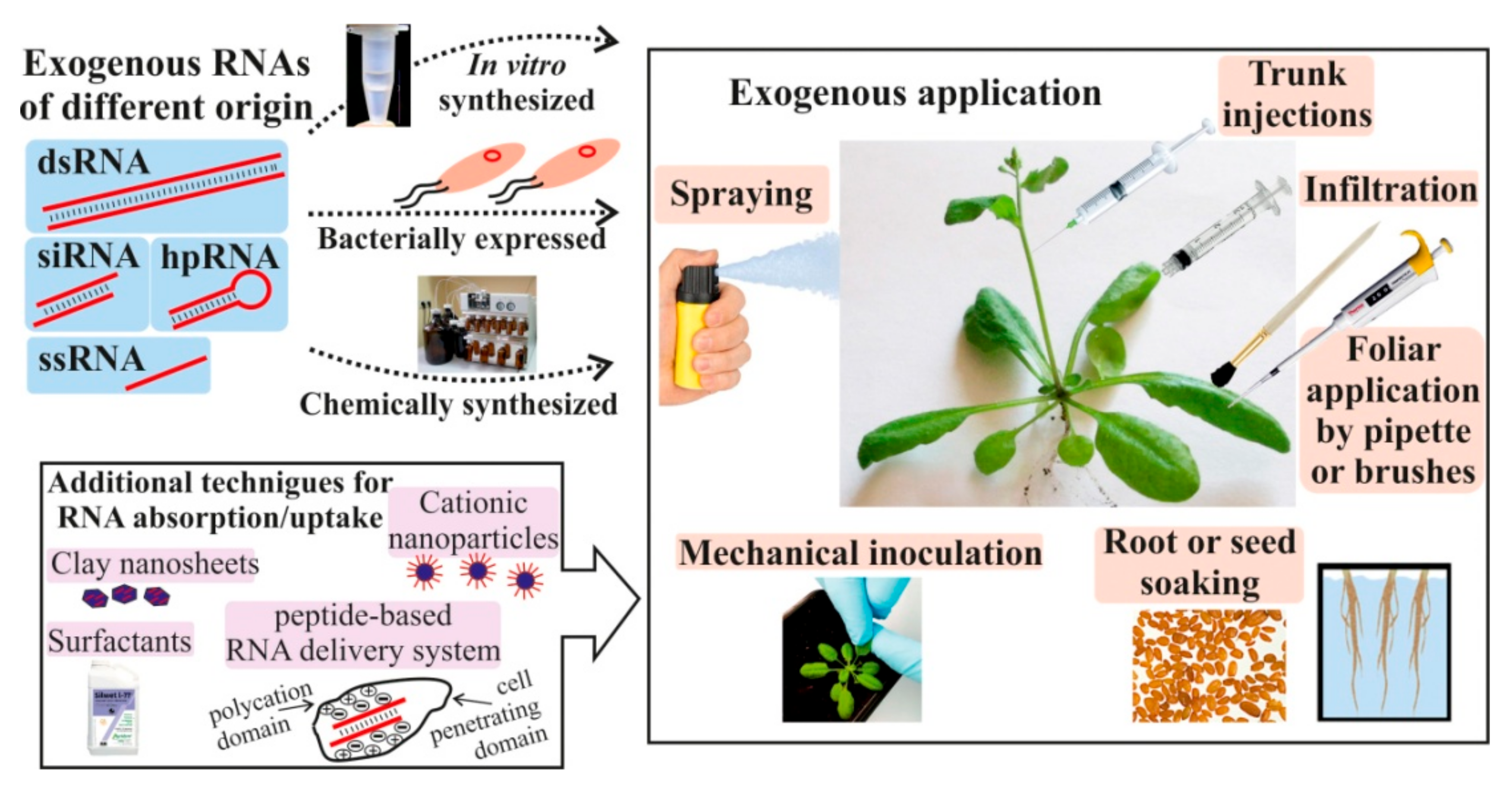

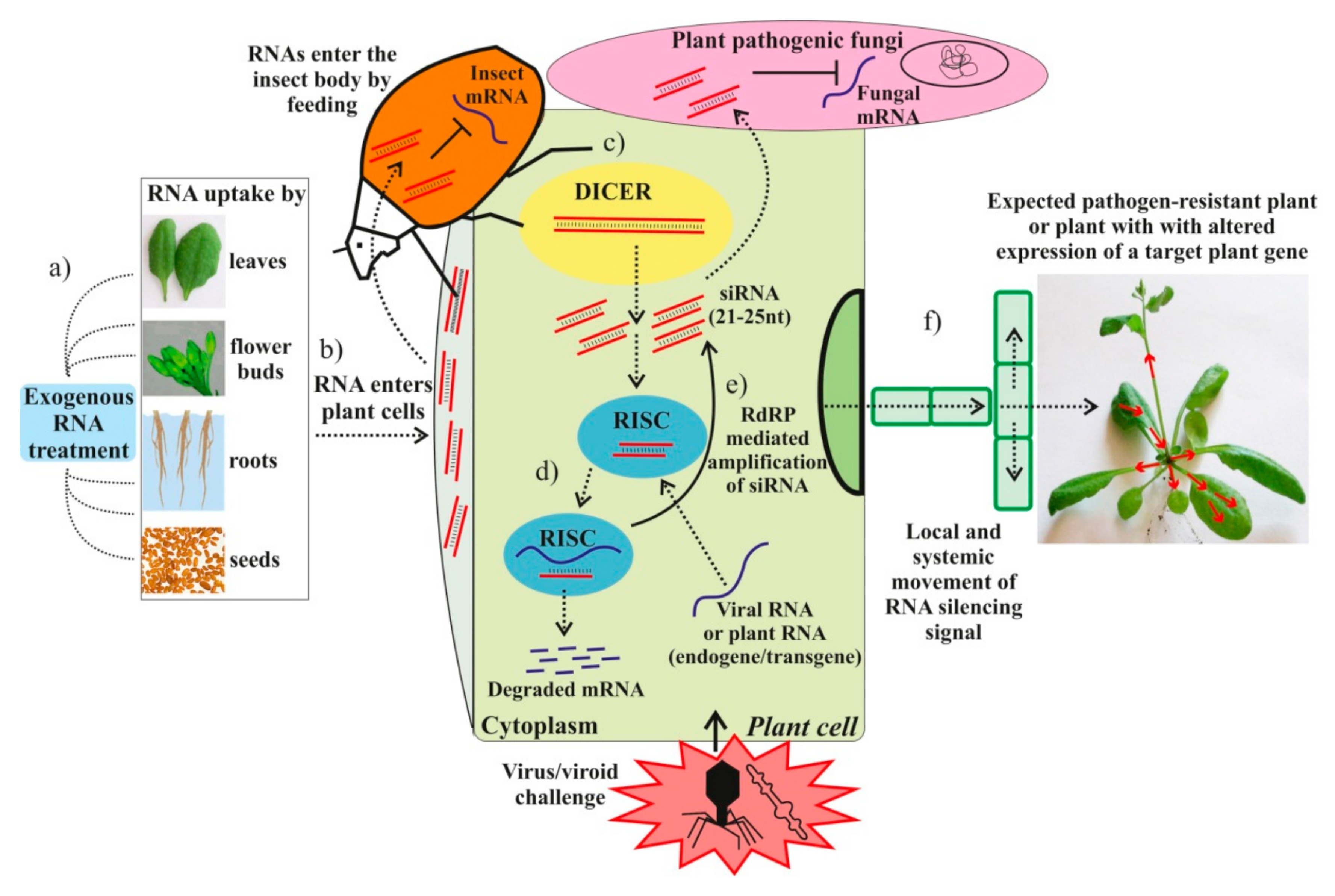

:1. Introduction

2. Induction of Plant Virus Resistance by Foliar-Applied dsRNAs, hpRNAs, and siRNAs

3. Plant Treatments with dsRNA for Insect Pest Resistance

4. Induction of Plant Fungal Resistance by Foliar-Applied dsRNAs and siRNAs

5. Silencing of Plant Endogenous Genes and Transgenes via dsRNA and siRNA Application

6. Stability of dsRNA in the Environment

7. Plant Nucleic Acid Recognition and Uptake

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACB | Asian corn borer (Ostrinia furnacalis) |

| ACP | Asian citrus psyllid |

| AK | Arginine kinase |

| AMV | Alfalfa mosaic virus |

| BCMV | Potyvirus bean common mosaic virus |

| BMSB | Brown marmorated stink bug |

| BPH | The brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) |

| CChMVd | Chrysanthemum chlorotic mottle viroid |

| Ces | Carboxylesterase |

| CEV | Citrus exocortis viroid |

| CHS | Chalcone synthase |

| CMV | Cucumber mosaic virus |

| CP | Coat protein |

| CPB | Colorado potato beetle |

| CymMV | Cymbidium mosaic virus |

| Cyp18A1 | A cytochrome P450 enzyme |

| CYP51 | Cytochrome P450 lanosterol C-14 α-demethylase |

| DCL | Dicer-like protein |

| DICER | DICER-LIKE ribonucleases |

| dpi | Days post inoculation |

| dpt | Days post treatment |

| dsRNA | Double-stranded RNA |

| EGFP | Enhanced green fluorescent protein |

| EPSPS | 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| GUS | β-glucuronidase |

| HC-Pro | The helper component-proteinase |

| hpRNA | Hairpin RNAs |

| hpt | Hours post-treatment |

| JHAMT | Juvenile hormone acid O-methyltransferase |

| KTI | Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitor |

| LDH | Layered double hydroxide clay nanosheets |

| MPK | Mitogen activated protein kinase |

| Nib | Potyviral nuclear inclusion b protein |

| NPTII | Neomycin phosphotransferase II |

| p126 | TMV silencing suppressor |

| PMMoV | Pepper mild mottle virus |

| PRSV | Papaya ringspot virus |

| PSTVd | Potato spindle tuber viroid |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RdRP | RNA-dependent RNA-polymerase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNAi | RNA interference or gene silencing |

| RP | Replicase protein |

| SCMV | Sugarcane mosaic virus |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| ssRNA | Single-stranded RNA |

| STM | Class I knotted-like homeodomain protein SHOOT MERISTEMLESS |

| TEV | Tobacco etch virus |

| β2Tub | β2–Tubulin |

| UTRs | 5′ and 3′ Untranslated regions |

| Vg | Vitellogenin |

| WER | A R2R3-type MyB-related transcription factor WEREWOLF |

| YFP | Yellow fluorescent protein |

| ZYMV | Zucchini yellow mosaic virus |

References

- Bawa, A.S.; Anilakumar, K.R. Genetically modified foods: Safety, risks and public concerns—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law Library of Congress (U.S.). Global Legal Research Directorate. Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms; Global Legal Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; p. 242. [Google Scholar]

- Kamthan, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Kamthan, M.; Datta, A. Small RNAs in plants: Recent development and application for crop improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, Q.; Smith, N.A.; Liang, G.; Wang, M.B. RNA silencing in plants: Mechanisms, technologies and applications in horticultural crops. Curr. Genom. 2016, 17, 476–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Weidner, D.A.; Hu, B.Y.; Newton, R.J.; Hu, X.H. Efficient delivery of small interfering RNA to plant cells by a nanosecond pulsed laser-inducedstress wave for posttranscriptional gene silencing. Plant Sci. 2006, 171, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.T.; Nguyen, A.; Ye, C.; Verchot, J.; Moon, J.H. Conjugated polymer nanoparticles for effective siRNA delivery to tobacco BY-2 protoplasts. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnamalai, N.; Kang, B.G.; Lee, W.S. Cationic oligopeptide-mediated delivery of dsRNA for post-transcriptional gene silencing in plantcells. FEBS Lett. 2004, 566, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šafářová, D.; Brázda, P.; Navrátil, M. Effect of artificial dsRNA on infection of pea plants by pea seed-borne mosaic virus. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2014, 50, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konakalla, N.C.; Kaldis, A.; Berbati, M.; Masarapu, H.; Voloudakis, A.E. Exogenous application of double-stranded RNA molecules from TMV p126 and CP genes confers resistance against TMV in tobacco. Planta 2016, 244, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitter, N.; Worrall, E.A.; Robinson, K.E.; Li, P.; Jain, R.G.; Taochy, C.; Fletcher, S.J.; Carroll, B.J.; Lu, G.Q.; Xu, Z.P. Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat. Plants 2017, 3, 16207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaldis, A.; Berbati, M.; Melita, O.; Reppa, C.; Holeva, M.; Otten, P.; Voloudakis, A. Exogenously applied dsRNA molecules deriving from the Zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV) genome move systemically and protect cucurbits against ZYMV. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 19, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, E.A.; Bravo-Cazar, A.; Nilon, A.T.; Fletcher, S.J.; Robinson, K.E.; Carr, J.P.; Mitter, N. Exogenous application of RNAi-inducing double-stranded RNA inhibits aphid-mediated tansmission of a plant virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, A.; Biedenkopf, D.; Furch, A.; Weber, L.; Rossbach, O.; Abdellatef, E.; Linicus, L.; Johannsmeier, J.; Jelonek, L.; Goesmann, A.; et al. An RNAi-based control of Fusarium graminearum infections through spraying of long dsRNAs involves a plant passage and is controlled by the fungal silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Weiberg, A.; Lin, F.M.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Huang, H.D.; Jin, H.L. Bidirectional cross-kingdom RNAi and fungal uptake of external RNAs confer plant protection. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin, A.G.; Wytinck, N.; Walker, P.L.; Girard, I.J.; Rashid, K.Y.; de Kievit, T.; Fernando, W.G.D.; Whyard, S.; Belmonte, M.F. Identification and application of exogenous dsRNA confers plant protection against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Botrytis cinerea. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.S.; Gu, K.X.; Duan, X.X.; Xiao, X.M.; Hou, Y.P.; Duan, Y.B.; Wang, J.X.; Zhou, M.G. A myosin5 dsRNA that reduces the fungicide resistance and pathogenicity of Fusarium asiaticum. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 150, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.S.; Gu, K.X.; Duan, X.X.; Xiao, X.M.; Hou, Y.P.; Duan, Y.B.; Wang, J.X.; Yu, N.; Zhou, M.G. Secondary amplification of siRNA machinery limits the application of spray-induced gene silencing. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 2543–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, K.X.; Song, X.S.; Xiao, X.M.; Duan, X.X.; Wang, J.X.; Duan, Y.B.; Hou, Y.P.; Zhou, M.G. A β2-tubulin dsRNA derived from Fusarium asiaticum confers plant resistance to multiple phytopathogens and reduces fungicide resistance. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 153, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Miguel, K.; Scott, J.G. The next generation of insecticides: dsRNA is stable as a foliar-applied insecticide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2016, 72, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Guan, R.; Guo, H.; Miao, X. New insights into an RNAi approach for plant defence against piercing-sucking and stem-borer insect pests. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 2277–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogoi, A.; Sarmah, N.; Kaldis, A.; Perdikis, D.; Voloudakis, A. Plant insects and mites uptake double-stranded RNA upon its exogenous application on tomato leaves. Planta 2017, 246, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.K.B.; Hunter, W.B.; Park, A.L.; Gundersen-Rindal, D.E. Double-stranded RNA oral delivery methods to induce RNA interference in phloem and plant-sap-feeding hemipteran insects. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 135, e57390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalakouras, A.; Jarausch, W.; Buchholz, G.; Bassler, A.; Braun, M.; Manthey, T.; Krczal, G.; Wassenegger, M. Delivery of hairpin RNAs and small RNAs into woody and herbaceous plants by trunk injection and petiole absorption. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, K.; Ohtani, M.; Yoshizumi, T.; Demura, T.; Kodama, Y. Local gene silencing in plants via synthetic dsRNA and carrier peptide. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalakouras, A.; Wassenegger, M.; McMillan, J.N.; Cardoza, V.; Maegele, I.; Dadami, E.; Runne, M.; Krczal, G.; Wassenegger, M. Induction of silencing in plants by high-pressure spraying of in vitro-synthesized small RNAs. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubrovina, A.S.; Aleynova, O.A.; Kalachev, A.V.; Suprun, A.R.; Ogneva, Z.V.; Kiselev, K.V. Induction of transgene suppression in plants via external application of synthetic dsRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Ding, L.; He, B.; Shen, J.; Xu, Z.; Yin, M.; Zhang, X. Systemic gene silencing in plants triggered by fluorescent nanoparticle-delivered double-stranded RNA. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9965–9969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, S.E.; Schwarzacher, T.; Othman, R.Y.; Harikrishna, J.A. dsRNA silencing of an R2R3-MYB transcription factor affects flower cell shape in a Dendrobium hybrid. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, P.; Mahajan, M.; Bhardwaj, J.; Yadav, S.K. Plant small RNAs: Biogenesis, mode of action and their roles in abiotic stresses. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2011, 9, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.; Kuo, Y.W.; Wuriyanghan, H.; Falk, B.W. RNA interference mechanisms and applications in plant pathology. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 581–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gautam, V.; Singh, S.; Sarkar Das, S.; Verma, S.; Mishra, V.; Mukherjee, S.; Sarkar, A.K. Plant small RNAs: Advancement in the understanding of biogenesis and role in plant development. Planta 2018, 248, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axtell, M.J. Classification and comparison of small RNAs from plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, F.; Martienssen, R.A. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mermigka, G.; Verret, F.; Kalantidis, K. RNA silencing movement in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2016, 58, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kehr, J.; Kragler, F. Long distance RNA movement. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Dunoyer, P.; Schott, G.; Himber, C.; Meyer, D.; Takeda, A.; Carrington, J.C.; Voinnet, O. Small RNA duplexes function as mobile silencing signals between plant cells. Science 2010, 328, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, A.; Melnyk, C.W.; Bassett, A.; Hardcastle, T.J.; Dunn, R.; Baulcombe, D.C. Small silencing RNAs in plants are mobile and direct epigenetic modification in recipient cells. Science 2010, 328, 872–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.B.; Masuta, C.; Smith, N.A.; Shimura, H. RNA silencing and plant viral diseases. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 2012, 25, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehl, A.; Soininen, M.; Poranen, M.M.; Heinlein, M. Synthetic biology approach for plant protection using dsRNA. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, A.; de Alba, A.E.M.; Flores, R.; Gago, S. Double-stranded RNA interferes in a sequence-specific manner with the infection of representative members of the two viroid families. Virology 2008, 371, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.E.; Mazumdar, P.; Hee, T.W.; Song, A.L.A.; Othman, R.Y.; Harikrishna, J.A. Crude extracts of bacterially-expressed dsRNA protect orchid plants against Cymbidium mosaic virus during transplantation from in vitro culture. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Tenllado, F.; Diaz-Ruiz, J.R. Double-stranded RNA-mediated interference with plant virus infection. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 12288–12297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenllado, F.; Martinez-Garcia, B.; Vargas, M.; Diaz-Ruiz, J.R. Crude extracts of bacterially expressed dsRNA can be used to protect plants against virus infections. BMC Biotechnol. 2003, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, D.F.; Zhang, J.A.; Jiang, H.B.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, S.W.; Cheng, B.J. Bacterially expressed dsRNA protects maize against SCMV infection. Plant Cell Rep. 2010, 29, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Yang, G.; Chen, Y.; Yan, P.; Tuo, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, P. Resistance of non-transgenic papaya plants to papaya ringspot virus (PRSV) mediated by intron-containing hairpin dsRNAs expressed in bacteria. Acta Virol. 2014, 58, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.H.; Sun, Z.N.; Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.Z.; Zhu, C.X.; Wen, F.J. Production of double-stranded RNA for interference with TMV infection utilizing a bacterial prokaryotic expression system. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamta, B.; Rajam, M.V. RNAi technology: A new platform for crop pest control. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2017, 23, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, J.A.; Bogaert, T.; Clinton, W.; Heck, G.R.; Feldmann, P.; Ilagan, O.; Johnson, S.; Plaetinck, G.; Munyikwa, T.; Pleau, M.; et al. Control of coleopteran insect pests through RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1322–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdam, G.V.; Simões, Z.L.; Guidugli, K.R.; Norberg, K.; Omholt, S.W. Disruption of vitellogenin gene function in adult honeybees by intra-abdominal injection of double-stranded RNA. BMC Biotechnol. 2003, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Gatehouse, J.A.; Fitches, E.C. A Systematic study of RNAi effects and dsRNA sability in Tribolium castaneum and Acyrthosiphon pisum, following injection ingestion of analogous dsRNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashuta, S.; Zhang, Y.J.; Wiggins, B.E.; Ramaseshadri, P.; Segers, G.C.; Johnson, S.; Meyer, S.E.; Kerstetter, R.A.; McNulty, B.C.; Bolognesi, R.; et al. Environmental RNAi in herbivorous insects. RNA 2015, 21, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killiny, N.; Hajeri, S.; Tiwari, S.; Gowda, S.; Stelinski, L.L. Double-stranded RNA uptake through topical application, mediates silencing of five CYP4 genes and suppresses insecticide resistance in Diaphorina citri. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.C.; Guan, R.B.; Miao, X.X. Lepidopteran insect species-specific, broad-spectrum, and systemic RNA interference by spraying dsRNA on larvae. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2015, 155, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Ryvkin, P.; Li, F.; Dragomir, I.; Valladares, O.; Yang, J.; Cao, K.; Wang, L.S.; Gregory, B.D. Genome-wide double-stranded RNA sequencing reveals the functional significance of base-paired RNAs in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.B.; Glick, E.; Paldi, N.; Bextine, B.R. Advances in RNA interference: dsRNA treatment in trees and grapevines for insect pest suppression. Southwest. Entomol. 2012, 37, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiberg, A.; Wang, M.; Lin, F.M.; Zhao, H.W.; Zhang, Z.H.; Kaloshian, I.; Huang, H.D.; Jin, H.L. Fungal small RNAs suppress plant immunity by hijacking host RNA interference pathways. Science 2013, 342, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Qiao, L.L.; Wang, M.; He, B.Y.; Lin, F.M.; Palmquist, J.; Huang, S.N.D.; Jin, H.L. Plants send small RNAs in extracellular vesicles to fungal pathogen to silence virulence genes. Science 2018, 360, 1126–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghag, S.B. Host induced gene silencing, an emerging science to engineer crop resistance against harmful plant pathogens. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 100, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Thomas, N.; Jin, H. Cross-kingdom RNA trafficking and environmental RNAi for powerful innovative pre- and post-harvest plant protection. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Jin, H. Spray-induced gene silencing: A powerful innovative strategy for crop protection. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeersch, L.; De Winne, N.; Nolf, J.; Bleys, A.; Kovařík, A.; Depicker, A. Transitive RNA silencing signals induce cytosine methylation of a transgenic but not an endogenous target. Plant J. 2013, 74, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadami, E.; Moser, M.; Zwiebel, M.; Krczal, G.; Wassenegger, M.; Dalakouras, A. An endogene-resembling transgene delays the onset of silencing and limits siRNA accumulation. FEBS Lett. 2013, 18, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadami, E.; Dalakouras, A.; Zwiebel, M.; Krczal, G.; Wassenegger, M. An endogene-resembling transgene is resistant to DNA methylation and systemic silencing. RNA Biol. 2014, 11, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeersch, L.; De Winne, N.; Depicker, A. Introns reduce transitivity proportionally to their length, suggesting that silencing spreads along the pre-mRNA. Plant J. 2010, 64, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Chen, Z. Improperly terminated, unpolyadenylated mRNA of sense transgenes is targeted by RDR6-mediated RNA silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 943–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M.; Croft, L.J.; Carroll, B.J. Intron splicing suppresses RNA silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2011, 68, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrovina, A.S.; Aleynova, O.A.; Suprun, A.R.; Ogneva, Z.V.; Kiselev, K.V. Transgene supression in plants by foliar application of in vitro-synthesized siRNAs. Appl. Microbiol. Biotech. 2019. Submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Sammons, R.; Ivashuta, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, D.; Feng, P.; Kouranov, A.; Andersen, S. Polynucleotide Molecules for Gene Regulation in Plants. U.S. Patent 2011/0296556 A1, 1 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karan, M.; Hicks, S.; Harding, R.M.; Teakle, D.S. Stability and extractability of double-stranded RNA of pangola stunt and sugarcane Fiji disease viruses in dried plant tissues. J. Virol. Methods 1991, 33, 211–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubelman, S.; Fischer, J.; Zapata, F.; Huizinga, K.; Jiang, C.; Uffman, J.; Levine, S.; Carson, D. Environmental fate of double-stranded RNA in agricultural soils. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.M.; Barragán Borrero, V.; van Leeuwen, D.M.; Lever, M.A.; Mateescu, B.; Sander, M. Environmental fate of RNA interference pesticides: Adsorption and degradation of double-stranded RNA molecules in agricultural soils. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 3027–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.R.; Zapata, F.; Dubelman, S.; Mueller, G.M.; Uffman, J.P.; Jiang, C.; Jensen, P.D.; Levine, S.L. Aquatic fate of a double-stranded RNA in a sediment-water system following an over-water application. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017, 36, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenski, D.M.; Butora, G.; Willingham, A.T.; Cooper, A.J.; Fu, W.; Qi, N.; Soriano, F.; Davies, I.W.; Flanagan, W.M. siRNA-optimized modifications for enhanced in vivo activity. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2012, 1, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faustinelli, P.C.; Power, I.L.; Arias, R.S. Detection of exogenous double-stranded RNA movement in in vitro peanut plants. Plant Biol. (Stuttg). 2018, 20, 444–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paungfoo-Lonhienne, C.; Lonhienne, T.G.; Mudge, S.R.; Schenk, P.M.; Christie, M.; Carroll, B.J.; Schmidt, S. DNA is taken up by root hairs and pollen, and stimulates root and pollen tube growth. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Ryu, C.M. Plant perceptions of extracellular DNA and RNA. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 956–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakushiji, S.; Ishiga, Y.; Inagaki, Y.; Toyoda, K.; Shiraishi, T.; Ichinose, Y. Bacterial DNA activates immunity in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2009, 75, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, S.; Song, G.C.; Ryu, C.M. Bacterial RNAs activate innate immunity in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehl, A.; Wyrsch, I.; Boller, T.; Heinlein, M. Double-stranded RNAs induce a pattern-triggered immune signaling pathway in plants. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1008–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duran-Flores, D.; Heil, M. Extracellular self-DNA as a damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) that triggers self-specific immunity induction in plants. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 72, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | RNA Type, Size and Origin | RNA Amount | RNA and Virus Application | Plant Host | Effect | Effect Maintenance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP gene of PMMoV, TEV, and AMV | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (PMMoV 315, 596, and 977 bp; TEV 1483 bp; AMV 1124 bp) | 5 µL of each dsRNA (2.5 µM) | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation) | Tobacco, pepper | Resistance to PMMoV, TEV, and AMV (assessed at 5–7 dpi) | Up to 21 dpi | Tenllado and Díaz-Ruíz (2001) [42] |

| RP gene of PMMoV | Crude extracts of bacterially expressed dsRNA (977 bp) | 10 µL of bacterial extract (1.5–3 µg/µL) | Mechanical inoculation or spraying with atomizer (virus co-inoculation or 1, 3, 5, and 7 dpt) | Tobacco | Resistance to PMMoV (assessed at 7 dpi, 30 dpi) | Up to 70 dpi | Tenllado et al. (2003) [43] |

| Viroid-specific dsRNAs | In vitro synthesized dsRNA and siRNA (less-than-full-length) | 1250 to 5000 molar excess of dsRNA; 100 molar excess of sRNA over viroid RNA | Mechanical inoculation (viroid co-inoculation) | Tomato, gynura, chrysanthemum | Resistance to PSTVd, CEVd and CChMVd (assessed along 20–50 dpi) | At least for 20 to 50 dpi | Carbonell et al. (2008) [40] |

| CP gene of TMV | Crude extracts of bacterially expressed dsRNA (480 bp) | 300 μg of RNA per tested plant (3 μg/μL) | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation) | Tobacco | Resistance to TMV (assessed along 10–30 dpi) | More than 60 dpi | Yin et al. (2009) [46] |

| CP gene of SCMV | Crude extracts of bacterially expressed hpRNA (147 or 140 bp stem) | Serial dilutions (1 mL) of total nucleic acid 3 µg/µL | Spraying (virus co-inoculation or 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 dpt) | Maize | Resistance to SCMV (assessed at 10, 20, 30 dpi) | At least up to 30 dpi | Gan et al. (2010) [44] |

| CP gene of PRSV | Crude extracts of bacterially expressed hpRNA (279 bp) | 100 μg of hpRNA | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation or 1, 2, 3, and 5 dpt) | Papaya | Resistance to PRSV (assessed along 10–30 dpi) | More than 60 dpi | Shen et al. (2014) [45] |

| CP gene of CymMV | Crude extracts of bacterially expressed dsRNAs and ssRNAs (237 bp) | 5 µg of total nucleic acid per 1 leaf (5 µg/mL) | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation) | Orchid | Resistance to CymMV (assessed at 30 dpi) | At least up to 30 dpi | Lau et al. (2014) [41] |

| p126 and CP genes of TMV | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (p126 666 bp; CP 480 bp) | 179.2 µg of p126 and 244.8 µg of CP dsRNAs per plant | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation) | Tobacco | Resistance to TMV (assessed along 20 dpi) | At least up to 20 dpi | Konakalla (2016) [9] |

| RP gene of PMMoV; 2b supressor of CMV2b | In vitro transcribed RP dsRNA (977 bp) and crude extracts of bacterially expressed 2b dsRNA (330 bp) naked or loaded into LDH | 125 µL per cm2 (1.25 µg of dsRNA and 3.75 µg of LDH) of the leaf surface | Spraying (virus inoculation 1, 5, 20 dpt) | Tobacco, cowpea | Resistance to PMMoV and CMV (assessed at 10 dpi) | At least for 10 dpi | Mitter et al. (2017) [10] |

| HC-Pro and CP genes of ZYMV | In vitro synthesized dsRNAs (HC-Pro 588 bp; CP 498 bp) | 40 to 60 μg of dsRNA (20 µL per leaf) | Mechanical inoculation (virus co-inoculation) | cucumber, watermelon and squash | Resistance to ZYMV (assessed along 20 dpi) | At least for 20 dpi | Kaldis et al. (2018) [11] |

| RP gene of TMV; GFP of TMV | Bacterially expressed or in vitro synthesized dsRNA (2 kb) | 5 μg of dsRNA | Mechanical inoculation; Spraying (virus co-inoculation or 1, 2, 4, or 7 dpt) | Tobacco | Resistance to TMV (assessed at 7, 9, and 14 dpi) | At least for 14 dpi | Niehl et al. (2018) [39] |

| NIb and CP genes of BCMV | Chemically synthesized dsRNAs (Nib 480 bp; CP 461 bp) applied directly or loaded into LDH | 100 μg of naked dsRNA (1 mL); or 250 ng of dsRNA loaded into LDH | Spraying (virus inoculation 1 or 5 dpt) | Tobacco, cowpea | Resistance to BCMV (assessed 10 and 20 dpi) | At least up to 10–20 dpi | Worrall et al. (2019) [12] |

| Target | RNA Type and Origin | RNA Amount | RNA Application and Feeding Assays | Plant Host | Effect | Effect Maintenance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyp18A1 and Ces genes of BPH; KTI gene of ACB | In vitro synthesized dsRNA | Rice—1 mL of dsRNA (1.0 mg/mL); maize—10 mL of dsRNA (0.5 mg/mL) | Root or seed soaking; larvae feeding 24 hpt | Rice, maize | Increased insect mortality rate | At least for 3–7 dpt | Li et al. (2015) [20] |

| Actin gene of CPB | In vitro transcribed dsRNA (50, 102, 208, 266, and 297 bp) | 5 μg of actin-dsRNA (200 µL) per single leaf of one plant | RNA coated over the leaf surface by the side of a 200 μL pipette tip; larvae feeding from 0.5 hpt for 7 days | potato | Lowered biological activity of CPB (monitored weight, instar stage, and mortality) | At least for 28 dpt | San Miquel and Scott (2016) [19] |

| HC-Pro gene of ZYMV | In vitro transcribed dsRNA (588 bp) | 10.5 µg (10 µL) of dsRNA onto the upper side per leaflets (of a single leaf) | Mechanical inoculation (gently rubbing the surface of carborundum-dusted leaves) | tomato | dsRNA detection in tomato (local and systemic leaves) and in insects (aphids, whiteflies, and mites) | Detection at 3, 10, and 14 dpt | Gogoi et al. (2017) [21] |

| JHAMT and Vg genes of BMSB | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (200–500 bp) | 5 µg or 20 µg in 300 µL of water (0.067 µg/µL or 0.017 µg/µL) | Immersion of the green beans in the dsRNA solution (3 h) | common bean | Decreased expression of JHAMT and Vg genes in BMSB | Ghosh et al. (2018) [22] | |

| AK gene of ACP | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (200–500 bp) | 200 mL of dsRNA (0.5 mg/mL); | RNA spraying; | citrange | Detection of the dsRNAs in the citrus plants; increased ACP mortality | dsRNA detection in plants 49 dpt | Ghosh et al. (2018) [22]; Hunter et al. (2012) [55] |

| 1 L (0.2 mg/mL), 100 mL (1.33 mg/mL), or 10 mL (1 mg/mL) of dsRNA | Soil/root drench application (soaking for 0.5 h); | citrange | |||||

| 6 mL (1.7 mg/mL) of dsRNA | trunk injections | citrange |

| Target | RNA Treatment | RNA Amount | RNA and Fungal Application | Plant Host | Effect Assessment | Effect Maintenance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP51A, CYP51B, and CYP51C genes of Fusarium graminearum | In vitro synthesized CYP3-dsRNA (791 bp); siRNAs produced from dsRNA by RNAse III | 10 μg dsRNA or siRNA per plate with six detached leaves (20 ng/μL in 500 µL of water) | RNA spraying; fungal inoculation 48 hpt | Barley | Inhibition of fungal growth and weaker disease symptoms; suppression of target fungal CYP51 mRNAs | At least for 6 dpi | Koch et al. (2016) [13] |

| DCL1 and DCL2 genes of Botrytis cinerea | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (490 bp); siRNAs produced in vitro from the dsRNA by RNAse III | 20 µL of RNA (20 ng/µL) per each plant specimen | RNA dropped onto the surface of each plant specimen; fungal inoculation or inoculation 1, 3, and 5 dpt | Tomato, strawberry, grape, lettuce, onion, rose, Arabidopsis | Inhibition of fungal growth and weaker disease symptoms; supression of fungal DCL transcripts | At least for 5 dpi | Wang et al. (2016) [14] |

| 59 target genes of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum | In vitro synthesized 20 dsRNAs (200–450 bp) | 10–25 μL of 200–500 ng dsRNA and 0.02–0.03% Silwet L-77 | Foliar RNA application to the leaf surface with Silwet L-77; fungal inoculation after leaf drying | Oilseed rape, Arabidopsis | Of the 59 dsRNAs tested, 20 showed antifungal activity against S. sclerotiorum and B. cinerea and weaker disease symptoms; suppression of fungal target genes | At least for 2–4 dpi | McLoughlin et al. (2018) [15] |

| Myosin 5 gene of Fusarium asiaticum | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (496 bp) | 0.1 pM Myo5 dsRNA | RNA spraying; fungal inoculation 12 hpt | Wheat | Antifungal activity and weaker disease symptoms; reduction of fungal resistance to phenamacril fungicide; suppression of fungal Myo5 transcript levels | Up to 7 dpi (Myo5-dsRNA); Up to 14 dpi (Myo5-dsRNA plus phenamacril) | Song et al. (2018a) [16] |

| β2Tub gene of Fusarium asiaticum | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (489 bp) | 30–40 ng/µL | RNA spraying after leaf wounding with quartz sand; fungal inoculation 12 hpt | Cucumber, soya, barley, wheat | Antifungal activity against F. asiaticum, B. cinerea, Magnaporthe oryzae, and Colletotrichum truncatum and weaker disease symptoms; reduction of F. asiaticum resistance to carbendazim fungicide | Up to 7 dpi (β2Tub–dsRNA); up to 14 dpi (β2Tub-dsRNA plus carbendazim) | Gu et al. (2019) [18] |

| Target | RNA Treatment | RNA Amount | RNA Application | Plant Host | Effect Assessment | Effect Maintenance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Transgenes | |||||||

| YFP transgene | In vitro synthesized short dsRNA (21 bp) in a complex with a carrier peptide | 100 µL of the RNA-peptide complex (20 pmol siRNA) | Infiltration of the complex into intact plant leaf cells using a syringe without a needle | Arabidopsis, poplar | Suppression of YFP protein level and fluorescence | At least for 24–36 hpt | Numata et al. (2014) [24] |

| GFP transgene | In vitro synthesized siRNAs | 100 µL of aqueous siRNA solutions (10 µM) | High-pressure spraying (using a conventional compressor and an air brush pistol) at the abaxial surface of leaves | Tobacco | Local and systemic GFP fluorescence suppression (detected 2–20 dpt) | Up to 20 dpt | Dalakouras et al. (2016) [25] |

| GUS transgene | Total RNA from dsRNA-expressing bacteria (~504 bp) | 100 µg of dsRNA with or without LDH | Sprayed with an atomizer | Arabidopsis | Reduction in GUS activity | Assessed 7 dpt | Mitter et al. (2017) [10] |

| EGFP and NPTII transgenes | In vitro synthesized dsRNAs (EGFP 720 bp; NPTII 599 bp) | 0.35 µg/µL (100 µL per 4-week-old plant) | Spreading with sterile individual soft brushes | Arabidopsis | Suppression of EGFP and NPTII mRNA levels; suppression of EGFP protein level and fluorescence; induction of EGFP and NPTII DNA methylation | At least for 7–14 dpt | Dubrovina et al. (2019) [26] |

| Plant Endogenous Genes | |||||||

| EPSPS gene | In vitro synthesized short dsRNAs (24 bp); long dsRNAs (200–250 bp) | 10 µL of dsRNA on each of four leaves per plant (0.024–0.8 nM) | Leaves pre-treatment by carborundum solution or surfactant solution | Palmer Amaranth (glyphosate-tolerant) | Suppressed EPSPS transcript and protein levels; improved glyphosate efficacy | at least for 48–72 hpt | Sammons et al. (2011) [68] |

| CHS gene | In vitro synthesized short dsRNA (21 bp) in a complex with a carrier peptide | 100 µL of protein carrier in a complex with the siRNA (6 pmol) | Infiltration of the complex into intact plant leaf cells using a syringe without a needle | Arabidopsis | Local loss of anthocyanin pigmentation | Assessed 2 dpt | Numata et al. (2014) [24] |

| STM and WER genes | A mixture of cationic fluorescent nanoparticles G2 and in vitro synthesized dsRNA (STM 450 bp; WER 550 bp) | 1 µg of dsRNA mixed with 3 µg of gene carrier G2 per root of Arabidopsis once every 24 h (3 days of treatment) | By pipette | Arabidopsis | Suppressed transcripts of STM and WER; retarded growth and reduced meristem size; fluorescence observed throughout the root system (24 hpt) | at least for 5–7 dpt | Jiang et al. (2014) [27] |

| MYB1 gene | Crude bacterial extract containing DhMYB1 dsRNA (430 bp) | 50 μL of crude bacterial extract (2 μg/μL, at 5 day intervals) | Mechanical inoculation (gently rubbing onto a flower bud using a latex-gloved finger) | hybrid orchid | Suppressed expression of DhMYB1; changed phenotype of floral cells (22, 25, and 29 dpt) | at least for 29 dpt | Lau et al. (2015) [28] |

| Mob1A, WRKY23, and Actin genes | In vitro synthesized dsRNA (Mob1A 554 bp; WRKY23 562 bp) | Arabidopsis and rice seeds or seedlings soaked in 0.2 or 1 mL dsRNA (1.0 mg/mL) | Root soaking | Arabidopsis, rice | Absorption of the dsRNA by plant roots; suppressed target genes; suppression of the root growth and seed germination; plants could not bolt or flower | at least up to 5–7 dpt | Li et al. (2015) [20] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dubrovina, A.S.; Kiselev, K.V. Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092282

Dubrovina AS, Kiselev KV. Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(9):2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092282

Chicago/Turabian StyleDubrovina, Alexandra S., and Konstantin V. Kiselev. 2019. "Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 9: 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092282

APA StyleDubrovina, A. S., & Kiselev, K. V. (2019). Exogenous RNAs for Gene Regulation and Plant Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(9), 2282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20092282