Unveiling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells’ Organizing Function in Regeneration

Abstract

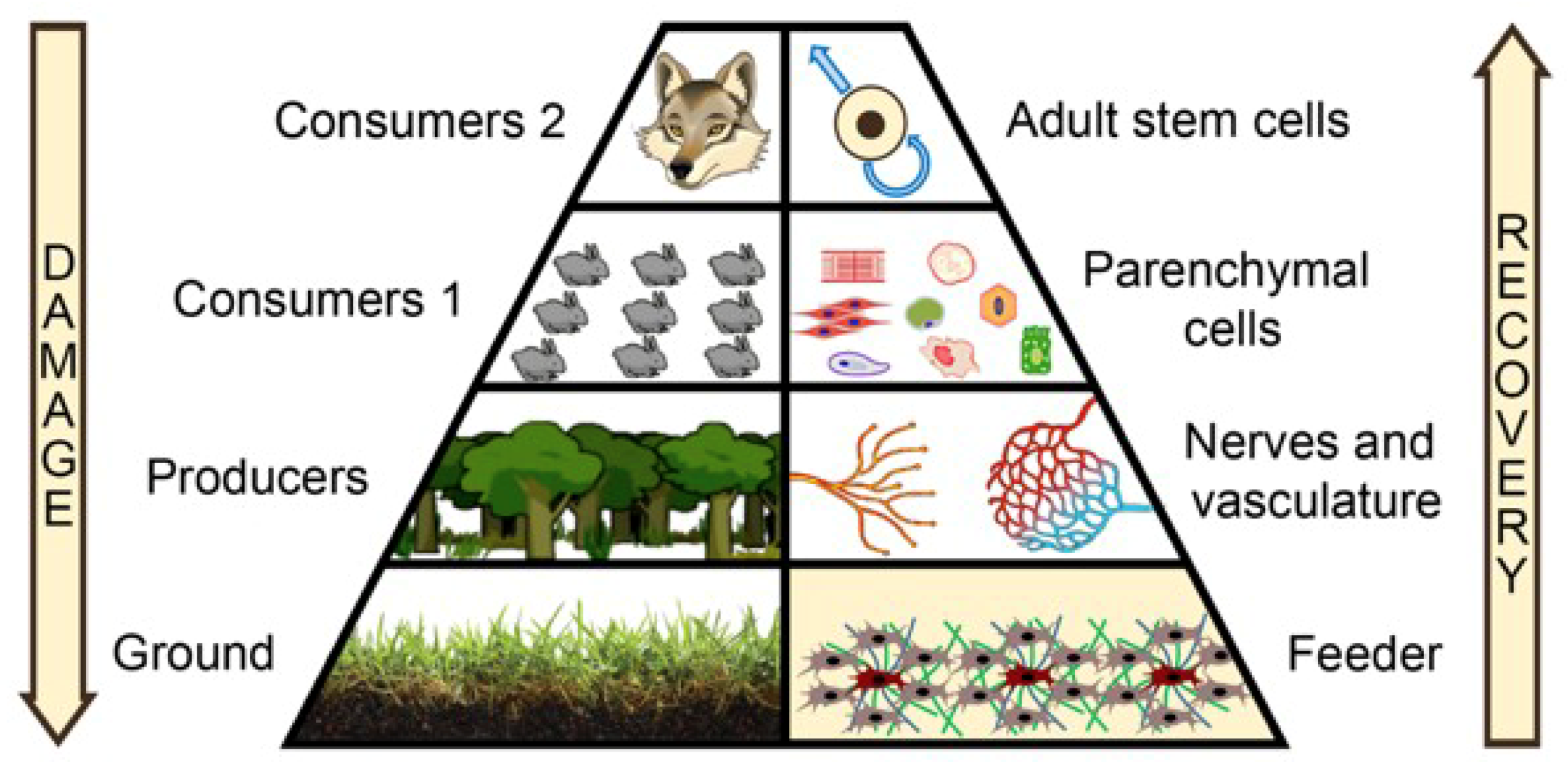

1. The Challenge for Stem Cell Therapy: Importance of Microenvironment

2. Shifting the Focus to the Microenvironment: Feeder Needed!

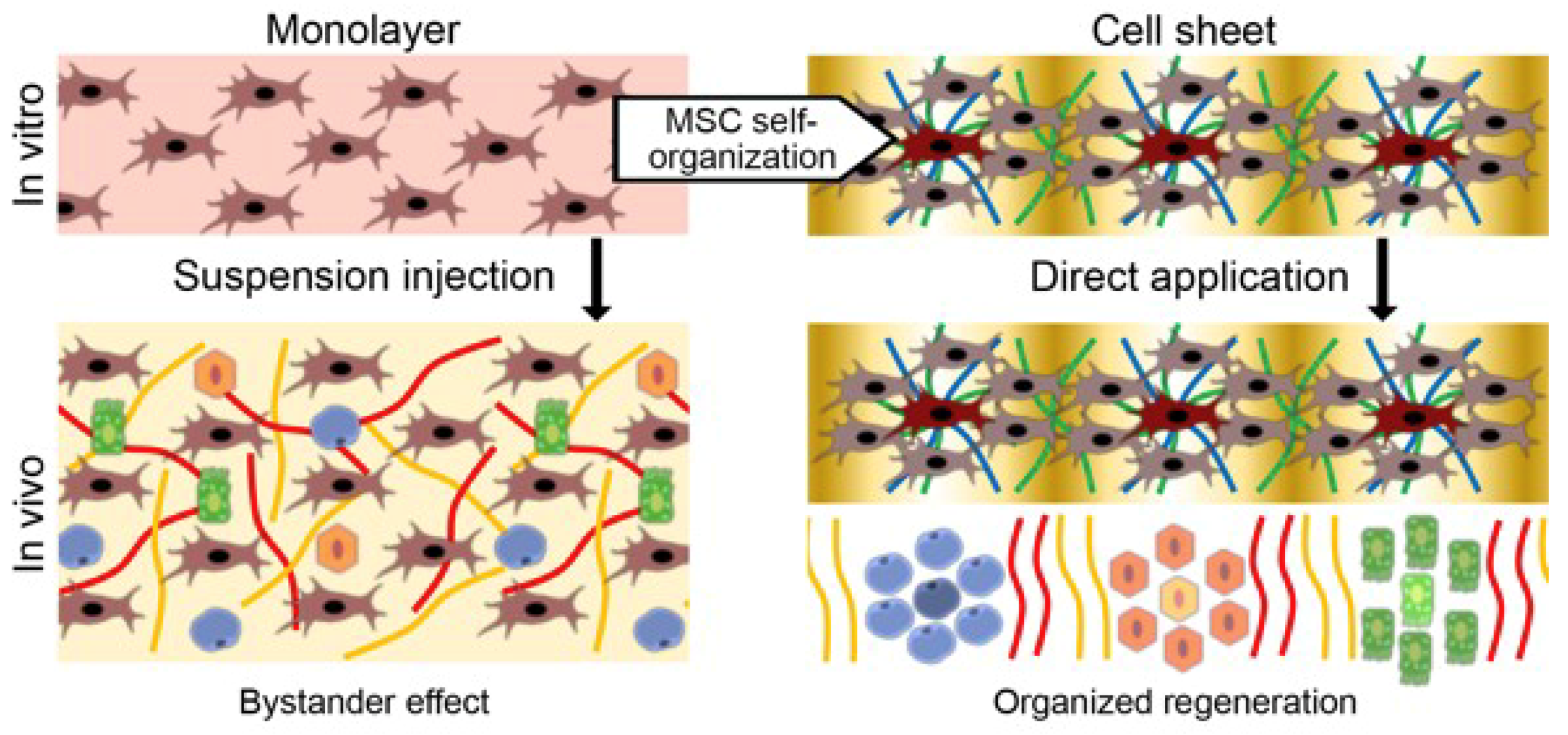

3. Rebuilding the Feeder: Focus on Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs)

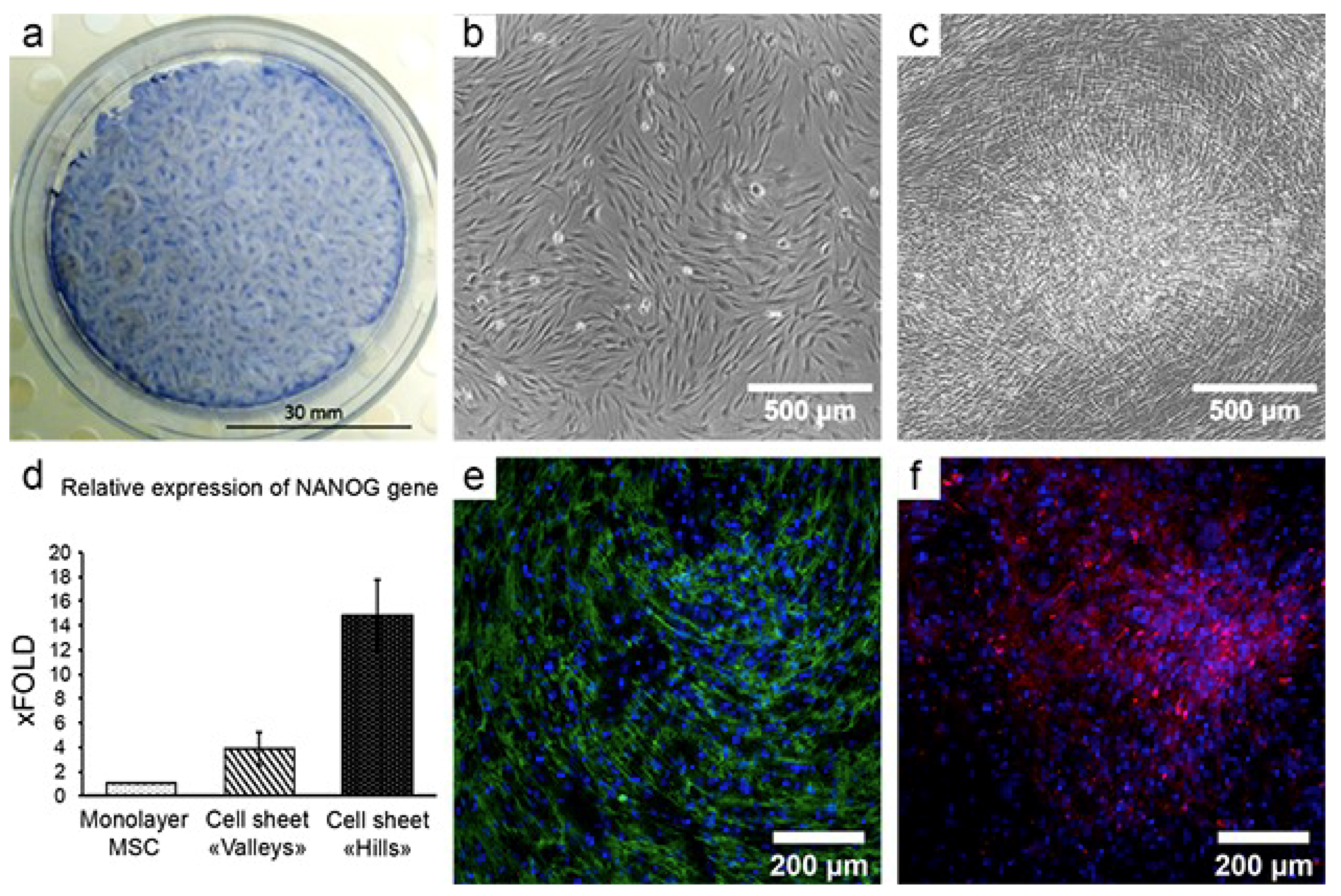

4. Cell Sheet Technology: Basics and Application

4.1. Delivery of MSCs Assembled in CS Results in a Strong and Reproducible Increase of Efficacy in Models of Tissue Damage

4.2. CS from MSCs Engraft, Show Vascularization and Facilitate MSC Survival and Proliferation

5. Role of MSC in Structure Organization in Development and Regeneration

6. MSCs as Organizers of Other Cell Types: ex vivo Evidence

7. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rao, M.; Mason, C.; Solomon, S. Cell therapy worldwide: An incipient revolution. Regen. Med. 2015, 10, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macrin, D.; Joseph, J.P.; Pillai, A.A.; Devi, A. Eminent Sources of Adult Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Therapeutic Imminence. Stem Cell Rev. 2017, 13, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, N.M.; Perrin, J. Ethical issues in stem cell research and therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2014, 5, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volarevic, V.; Markovic, B.S.; Gazdic, M.; Volarevic, A.; Jovicic, N.; Arsenijevic, N.; Armstrong, L.; Djonov, V.; Lako, M.; Stojkovic, M. Ethical and Safety Issues of Stem Cell-Based Therapy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 15, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeder, I.S. Stem cells: Are we ready for therapy? Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1213, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Baksh, D.; Song, L.; Tuan, R.S. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: Characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2004, 8, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharaibeh, B.; Lavasani, M.; Cummins, J.H.; Huard, J. Terminal differentiation is not a major determinant for the success of stem cell therapy - cross-talk between muscle-derived stem cells and host cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2011, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savukinas, U.B.; Enes, S.R.; Sjoland, A.A.; Westergren-Thorsson, G. Concise Review: The Bystander Effect: Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Mediated Lung Repair. Stem Cells 2016, 3, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, J.J.; Arellano, J.I.; Macklis, J.D.; Rakic, P. Everything that glitters isn’t gold: A critical review of postnatal neural precursor analyses. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 612–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. Stem cells and niches: Mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell 2008, 132, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells 1978, 4, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scadden, D.T. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature 2006, 441, 1075–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, E.M.; Reddien, P.W. The cellular basis for animal regeneration. Dev. Cell 2011, 21, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, A. Mesenchymal stem cell delivery routes and fate. Int. J. Stem Cells 2008, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggenhofer, E.; Luk, F.; Dahlke, M.H.; Hoogduijn, M.J. The life and fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Front Immunol. 2014, 5, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.A.; Evans, R.A. Population Dynamics after Wildfires in Sagebrush Grasslands. J. Range Manage. 1978, 31, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, E.F.; Dickman, C.R. Mechanisms of recovery after fire by rodents in the Australian environment: A review. Wildlife Res. 1999, 26, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, C.D.; Gardiner, D.M. Positional Information Is Reprogrammed in Blastema Cells of the Regenerating Limb of the Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavino, M.A.; Wenemoser, D.; Wang, I.E.; Reddien, P.W. Tissue absence initiates regeneration through follistatin-mediated inhibition of activin signaling. Elife 2013, 2, e00247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, S.; Fujii, Y.; Winters, S.J. Follistatin production by skin fibroblasts and its regulation by dexamethasone. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2001, 172, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, B.F.; Bouchentouf, M.; Rousseau, J.; Tremblay, J.P. Overexpression of follistatin in human myoblasts increases their proliferation and differentiation, and improves the graft success in SCID mice. Cell Transplant 2009, 18, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, E.D.; Lochte, H.L., Jr.; Lu, W.C.; Ferrebee, J.W. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1957, 257, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, R.; Beckett, T.; Goncz, K.K.; Suratt, B.T.; Weiss, D.J. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow-derived cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 173, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, A.; Kozlowska, U. Mesenchymal stromal cells and tissue-specific progenitor cells: Their role in tissue homeostasis. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4285215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosinski, C.; Li, V.S.; Chan, A.S.; Zhang, J.; Ho, C.; Tsui, W.Y.; Chan, T.L.; Mifflin, R.C.; Powell, D.W.; Yuen, S.T. Gene expression patterns of human colon tops and basal crypts and BMP antagonists as intestinal stem cell niche factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15418–15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kfoury, Y.; Scadden, D.T. Mesenchymal cell contributions to the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Time to Change the Name! Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimarino, A.M.; Caplan, A.I.; Bonfield, T.L. Mesenchymal stem cells in tissue repair. Front Immunol. 2013, 4, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, M.E.; Fibbe, W.E. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubina, K.; Kalinina, N.; Efimenko, A.; Lopatina, T.; Melikhova, V.; Tsokolaeva, Z.; Sysoeva, V.; Tkachuk, V.; Parfyonova, Y. Adipose stromal cells stimulate angiogenesis via promoting progenitor cell differentiation, secretion of angiogenic factors, and enhancing vessel maturation. Tissue Eng. Part A 2009, 15, 2039–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, N.; Kharlampieva, D.; Loguinova, M.; Butenko, I.; Pobeguts, O.; Efimenko, A.; Ageeva, L.; Sharonov, G.; Ischenko, D.; Alekseev, D.; et al. Characterization of secretomes provides evidence for adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells subtypes. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konala, V.B.; Mamidi, M.K.; Bhonde, R.; Das, A.K.; Pochampally, R.; Pal, R. The current landscape of the mesenchymal stromal cell secretome: A new paradigm for cell-free regeneration. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopatina, T.; Bruno, S.; Tetta, C.; Kalinina, N.; Porta, M.; Camussi, G. Platelet-derived growth factor regulates the secretion of extracellular vesicles by adipose mesenchymal stem cells and enhances their angiogenic potential. Cell Commun. Signal 2014, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagaradze, G.D.; Basalova, N.A.; Kirpatovsky, V.I.; Ohobotov, D.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Balabanyan, V.Y.; Kamalov, A.A.; Efimenko, A.Y. Application of rat cryptorchidism model for the evaluation of mesenchymal stromal cell secretome regenerative potential. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1428–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, F.J.; Eiro, N.; Cid, S.; Schneider, J.; Perez-Fernandez, R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagaradze, G.D.; Nimiritsky, P.P.; Akopyan, Z.A.; Makarevich, P.I.; Efimenko, A.Y. “Cell-Free Therapeutics” from Components Secreted by Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as a Novel Class of Biopharmaceuticals. In Biopharmaceuticals; Chen, M.-K.Y.A.Y.-C., Ed.; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zubkova, E.S.; Beloglazova, I.B.; Makarevich, P.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Sukhareva, O.Y.; Shestakova, M.V.; Dergilev, K.V.; Parfyonova, Y.V.; Menshikov, M.Y. Regulation of Adipose Tissue Stem Cells Angiogenic Potential by Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha. J. Cell Biochem. 2016, 117, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, E.K.; Makarevich, P.I.; Tsokolaeva, Z.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Tkachuk, V.A.; Parfyonova, Y.V. Transplantation of modified human adipose derived stromal cells expressing VEGF165 results in more efficient angiogenic response in ischemic skeletal muscle. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubkova, E.S.; Semenkova, L.N.; Dudich, I.V.; Dudich, E.I.; Khromykh, L.M.; Makarevich, P.I.; Parfenova, E.V.; Men’shikov, M. [Recombinant human alpha-fetoprotein as a regulator of adipose tissue stromal cell activity]. Bioorg. Khim. 2012, 38, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, P.; Cao, X.; Frenette, P.S.; Mao, J.J.; Robey, P.G.; Simmons, P.J.; Wang, C.-Y. The meaning, the sense and the significance: Translating the science of mesenchymal stem cells into medicine. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: The Past, the Present, the Future. Cartilage 2010, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Mackay, A.M.; Beck, S.C.; Jaiswal, R.K.; Douglas, R.; Mosca, J.D.; Moorman, M.A.; Simonetti, D.W.; Craig, S.; Marshak, D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 1999, 284, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, N.I.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Rubina, K.A.; Parfenova, Y.V.; Tkachuk, V.A. Mesenchymal stem cells in tissue growth and repair. Acta Nat. 2011, 3, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Choi, E.; Cha, M.-J.; Hwang, K.-C. Cell adhesion and long-term survival of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells: A prerequisite for cell therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 632902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.J.; Lee, H.W.; Kalimuthu, S.; Kim, T.J.; Kim, H.M.; Baek, S.H.; Zhu, L.; Oh, J.M.; Son, S.H.; Chung, H.Y. In vivo migration of mesenchymal stem cells to burn injury sites and their therapeutic effects in a living mouse model. J. Control. Release 2018, 279, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaeth, E.; Klopp, A.; Dembinski, J.; Andreeff, M.; Marini, F. Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: Defining the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semedo, P.; Palasio, C.G.; Oliveira, C.D.; Feitoza, C.Q.; Gonçalves, G.M.; Cenedeze, M.A.; Wang, P.M.; Teixeira, V.P.; Reis, M.A.; Pacheco-Silva, A. Early modulation of inflammation by mesenchymal stem cell after acute kidney injury. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battiwalla, M.; Hematti, P. Mesenchymal stem cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cytotherapy 2009, 11, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushida, A.; Yamato, M.; Isoi, Y.; Kikuchi, A.; Okano, T. A noninvasive transfer system for polarized renal tubule epithelial cell sheets using temperature-responsive culture dishes. Eur. Cell Mater. 2005, 10, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okano, T.; Yamada, N.; Sakai, H.; Sakurai, Y. A novel recovery system for cultured cells using plasma-treated polystyrene dishes grafted with poly(N-isopropylacrylamide). J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1993, 27, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergilev, K.V.; Makarevich, P.I.; Tsokolaeva, Z.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Beloglazova, I.B.; Zubkova, E.S.; Menshikov, M.Y.; Parfyonova, Y.V. Comparison of cardiac stem cell sheets detached by Versene solution and from thermoresponsive dishes reveals similar properties of constructs. Tissue Cell 2017, 49, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xing, Q.; Zhai, Q.; Tahtinen, M.; Zhou, F.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.; Qi, S.; Zhao, F. Pre-vascularization Enhances Therapeutic Effects of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Sheets in Full Thickness Skin Wound Repair. Theranostics 2017, 7, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.L.; Lee, J.; Kim, E.H.; Shin, D. Plasticity of oral mucosal cell sheets for accelerated and scarless skin wound healing. Oral Oncol. 2017, 75, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, G.T.S.; Michelmore, A.; Smith, L.E.; Whittle, J.D.; Short, R.D. Cell sheets in cell therapies. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ma, J.; Gao, Y.; Yang, L. Cell sheet technology: A promising strategy in regenerative medicine. Cytotherapy 2018, 21, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, S.; Shimizu, T. Three-dimensional cardiac tissue fabrication based on cell sheet technology. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 96, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannachi, I.E.; Yamato, M.; Okano, T. Cell sheet technology and cell patterning for biofabrication. Biofabrication 2009, 1, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, K.; Utoh, R.; Nagase, K.; Okano, T. Cell sheet approach for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dergilev, K.V.; Makarevich, P.I.; Menshikov, M.Y.; Parfyonova, E.V. Application of tissue engineered constructs on the basis of cell sheets for restoration of tissues and organs. Genes Cells 2016, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Makarevich, P.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Gluhanyuk, E.V.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Dergilev, K.V.; Shevchenko, E.K.; Sharonov, G.V.; Gallinger, J.O.; Rodina, P.A.; Sarkisyan, S.S. Enhanced angiogenesis in ischemic skeletal muscle after transplantation of cell sheets from baculovirus-transduced adipose-derived stromal cells expressing VEGF165. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.N.; Liao, H.T.; Li, K.C.; Chen, H.H.; Yen, T.C.; Makarevich, P.; Parfyonova, Y.; Hu, Y.C. Adipose-derived stem cell sheets functionalized by hybrid baculovirus for prolonged GDNF expression and improved nerve regeneration. Biomaterials 2017, 140, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergilev, K.; Tsokolaeva, Z.; Makarevich, P.; Beloglazova, I.; Zubkova, E.; Boldyreva, M.; Ratner, E.; Dyikanov, D.; Menshikov, M.; Ovchinnikov, A.; et al. C-Kit Cardiac Progenitor Cell Based Cell Sheet Improves Vascularization and Attenuates Cardiac Remodeling following Myocardial Infarction in Rats. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3536854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.S.; Fang, Y.H.; Lu, C.H.; Chiu, S.C.; Yeh, C.L.; Yen, T.C.; Parfyonova, Y.; Hu, Y.C. Baculovirus-transduced, VEGF-expressing adipose-derived stem cell sheet for the treatment of myocardium infarction. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarevich, P.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Dergilev, K.V.; Gluhanyuk, E.V.; Gallinger, J.O.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Tkachuk, V.A.; Parfyonova, Y.V. Transplantation of cell sheets from adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells effectively induces angiogenesis in ischemic skeletal muscle. Genes Cells 2015, 10, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrushkina, N.A.; Makarevich, O.A.; Nimiritskiy, P.P.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Danilova, N.V.; Parfyonova, Y.V.; Makarevich, P.I.; Tkachuk, V.A. Adipose mesenchymal stromal cell sheets accelerate healing in rat model of deep wound. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, A86. [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi, K.; Okano, T. Hepatocyte Transplantation: Cell Sheet Technology for Liver Cell Transplantation. Curr. Transplant Rep. 2017, 4, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, F.; Ho, S.T.; Woodruff, M.A.; Lim, T.M.; Hutmacher, D.W. Combined marrow stromal cell-sheet techniques and high-strength biodegradable composite scaffolds for engineered functional bone grafts. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Qi, Y.; Niu, L.; Di, T.; Zhong, J.; Fang, T.; Yan, W. Application of the cell sheet technique in tissue engineering. Biomed. Rep. 2015, 3, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, W.E.; Zeng, C. How to Improve the Survival of Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cell in Ischemic Heart? Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 9682757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tano, N.; Narita, T.; Kaneko, M.; Ikebe, C.; Coppen, S.R.; Campbell, N.G.; Shiraishi, M.; Shintani, Y.; Suzuki, K. Epicardial placement of mesenchymal stromal cell-sheets for the treatment of ischemic cardiomyopathy; in vivo proof-of-concept study. Mol. Ther. 2014, 22, 1864–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xie, T.; Sun, Y. Towards organogenesis and morphogenesis in vitro: Harnessing engineered microenvironment and autonomous behaviors of pluripotent stem cells. Integ. Biol. 2018, 10, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobstein, C. Epithelio-mesenchymal specificity in the morphogenesis of mouse sub-mandibular rudiments in vitro. J. Exp. Zool. 1953, 124, 383–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herriges, M.; Morrisey, E.E. Lung development: Orchestrating the generation and regeneration of a complex organ. Development 2014, 141, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golosow, N.; Grobstein, C. Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1962, 4, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, A.; Anderson, R.H.; Markwald, R.R.; Webb, S.; Brown, N.A.; Viragh, S.; Moorman, A.F.; Lamers, W.H. Atrial development in the human heart: An immunohistochemical study with emphasis on the role of mesenchymal tissues. Anat. Rec. 2000, 259, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatini, V.; Huh, S.O.; Herzlinger, D.; Soares, V.C.; Lai, E. Essential role of stromal mesenchyme in kidney morphogenesis revealed by targeted disruption of Winged Helix transcription factor BF-2. Gene. Dev. 1996, 10, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hum, S.; Rymer, C.; Schaefer, C.; Bushnell, D.; Sims-Lucas, S. Ablation of the renal stroma defines its critical role in nephron progenitor and vasculature patterning. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Evason, K.J.; Asahina, K.; Stainier, D.Y. Hepatic stellate cells in liver development, regeneration, and cancer. J. Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, S.F. Developmental Biology; Sinauer: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Birchmeier, C.; Birchmeier, W. Molecular Aspects of Mesenchymal-Epithelial Interactions. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1993, 9, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.B.; Smith, J.C. Growth factors as morphogens: Do gradients and thresholds establish body plan? Trends Genet. 1991, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Ma, D.; Liu, B.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, D.; Gao, P. Preparation of three-dimensional vascularized MSC cell sheet constructs for tissue regeneration. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 301279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takebe, T.; Enomura, M.; Yoshizawa, E.; Kimura, M.; Koike, H.; Ueno, Y.; Matsuzaki, T.; Yamazaki, T.; Toyohara, T.; Osafune, K.; et al. Vascularized and Complex Organ Buds from Diverse Tissues via Mesenchymal Cell-Driven Condensation. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimiritsky, P.P.; Alexandrushkina, N.A.; Sagaradze, G.D.; Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.A.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Makarevich, P.I. MSC self-organization in vitro is concordant with elevation of regenerative potential and characteristics related to stem cell niche function. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, A62. [Google Scholar]

- Nimiritsky, P.P.; Makarevich, O.A.; Sagaradze, G.D.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Eremichev, R.Y.; Makarevich, P.I.; Tkachuk, V.A. Evaluation of mechanisms underlying regenerative potential of cell sheets from human mesenchymal stromal cells. Hum. Gene Ther. 2017, 28, A100. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, L.Q.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.H.; Yu, M.F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, B.; Cheng, K.; Weng, W.J.; Wang, H.M. Engineering prevascularized composite cell sheet by light-induced cell sheet technology. Rsc. Adv. 2017, 7, 32468–32477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, P. “Mesenchymal” Stem Cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 2014, 30, 677–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotova, P.D.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Rogachevskaja, O.A.; Bystrova, M.F.; Kolesnikova, A.S.; Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.A.; Fadeeva, J.I.; Tkachuk, V.A.; Kolesnikov, S.S. Functional expression of adrenoreceptors in mesenchymal stromal cells derived from the human adipose tissue. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 1899–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.A.; Fadeeva, J.I.; Kanareikina, M.A.; Kalinina, N.I.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Dyikanov, D.T.; Stambolsky, D.V.; Tkachuk, V.A. Activation of beta-adrenergic receptors is required for elevated alpha1A-adrenoreceptors expression and signaling in mesenchymal stromal cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczkova, L.; Sedlarikova, L.; Hajek, R.; Sevcikova, S. TGF-beta - an excellent servant but a bad master. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massague, J. TGFbeta signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozney, J.M. Overview of bone morphogenetic proteins. Spine 2002, 27, S2–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, E. Bone morphogenetic proteins: An overview of therapeutic applications. Orthopedics 2001, 24, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ducy, P.; Karsenty, G. The family of bone morphogenetic proteins. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrae, J.; Gallini, R.; Betsholtz, C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1276–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, L.T. Signal transduction by the platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Science 1989, 243, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePaolo, L.V. Inhibins, activins, and follistatins: The saga continues. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1997, 214, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenken, A.; Mohammadi, M. The FGF family: Biology, pathophysiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Ornitz, D.M. Fibroblast growth factors: From molecular evolution to roles in development, metabolism and disease. J. Biochem. 2011, 149, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarevich, P.; Tsokolaeva, Z.; Shevelev, A.; Rybalkin, I.; Shevchenko, E.; Beloglazova, I.; Vlasik, T.; Tkachuk, V.; Parfyonova, Y. Combined transfer of human VEGF165 and HGF genes renders potent angiogenic effect in ischemic skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Zhang, H.; Hou, J.; Wan, L.; Cheng, W.; Wang, X.; Dong, D.; Chen, C.; Xia, J.; Guo, J.; et al. VEGF secreted by mesenchymal stem cells mediates the differentiation of endothelial progenitor cells into endothelial cells via paracrine mechanisms. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 1667–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyreva Mcapital, A.C.; Bondar, I.V.; Stafeev, I.S.; Makarevich, P.I.; Beloglazova, I.B.; Zubkova, E.S.; Shevchenko, E.K.; Molokotina, Y.D.; Karagyaur, M.N.; Rsmall, A.C.C.I.E.C.; et al. Plasmid-based gene therapy with hepatocyte growth factor stimulates peripheral nerve regeneration after traumatic injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarevich, P.I.; Dergilev, K.V.; Tsokolaeva, Z.I.; Boldyreva, M.A.; Shevchenko, E.K.; Gluhanyuk, E.V.; Gallinger, J.O.; Menshikov, M.Y.; Parfyonova, Y.V. Angiogenic and pleiotropic effects of VEGF165 and HGF combined gene therapy in a rat model of myocardial infarction. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagyaur, M.; Dyikanov, D.; Makarevich, P.; Semina, E.; Stambolsky, D.; Plekhanova, O.; Kalinina, N.; Tkachuk, V. Non-viral transfer of BDNF and uPA stimulates peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 74, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semina, E.V.; Rubina, K.A.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Makarevich, P.I.; Parfyonova, Y.V.; Tkachuk, V.A. Urokinase System Involves in Vascular Cells Migration and Regulates the Growth and Branching of Capillaries. Tsitologiia 2015, 57, 689–698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sisson, T.H.; Nguyen, M.H.; Yu, B.; Novak, M.L.; Simon, R.H.; Koh, T.J. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator increases hepatocyte growth factor activity required for skeletal muscle regeneration. Blood 2009, 114, 5052–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, M.S.; Matsumoto, K.; Nakamura, T.; Orci, L.; Montesano, R. Hepatocyte growth factor increases urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA) and u-PA receptor expression in Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 20493–20496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, M.D.; Benoit, D.S. Agonism of Wnt-beta-catenin signalling promotes mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) expansion. J. Tissue Eng. Regen Med. 2015, 9, E13–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Nurcombe, V.; Cool, S.M. Wnt signaling controls the fate of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene 2009, 433, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, M.K.; Shao, C.; Wang, J.; Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Collier, Z.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F.; Huang, J.; et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling plays an ever-expanding role in stem cell self-renewal, tumorigenesis and cancer chemoresistance. Genes Dis. 2016, 3, 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A. Population ecology issues in tumor growth. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 2542–2547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagy, J.D. The ecology and evolutionary biology of cancer: A review of mathematical models of necrosis and tumor cell diversity. Math Biosci. Eng. 2005, 2, 381–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Grove, O.; Gillies, R.J. Quantitative imaging in cancer evolution and ecology. Radiology 2013, 269, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papayannopoulou, T.; Scadden, D.T. Stem-cell ecology and stem cells in motion. Blood 2008, 111, 3923–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| MSC Property/Function | Reference |

|---|---|

| Ubiquitous location in tissues and organs | [40,41] |

| Multipotency and high proliferative potential | [42,43] |

| Survival under stress conditions and inflammation | [44,45] |

| Immunomodulation and reduction of inflammation | [29,46,47] |

| Active pleiotropic secretome comprising of ECM components, growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular vesicles | [31,32,35] |

| Ability to support and regulate other cell types in vivo | [30,48] |

| Growth Factor/Cytokine and its Function | Function and Role in Organized Regeneration | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Transforming growth factor β | Control of fibrosis and morphogenesis, attenuation of immune response and cell survival under stress, activation of ECM production in various cell types | [90,91] |

| Bone morphogenetic protein family | Resident stem cell activation and control, regeneration and turnover of osseous tissues, control of anterior/posterior axis | [92,93,94] |

| Platelet-derived growth factors | Potent mitogens in cells of mesenchymal origin, chemoattractant for stromal cells, mediator of wound healing and resident MSC activation | [95,96] |

| Follistatin | Specific inhibitor of activin A and potent cell cycle controller; plays a crucial role in “shape control” of muscle and skin preventing excessive growth; known to be a part of “missing tissue” sensory system activating regenerative program | [19,97] |

| Fibroblast growth factors | "Promiscuous" growth factors involved in development, angiogenesis, nerve growth, stromal cell proliferation, and fibrosis after damage, as well as ECM deposition and remodeling | [98,99] |

| Vascular endothelial growth factors | Control of angiogenesis, cell survival under stress, and pro-inflammatory effects in vascular cells; potent mitogen for MSC and resident stem cells as well as a crucial player in stem cell activation | [100,101,102] |

| Hepatocyte growth factor | Also known as “scattering factor,” it controls cell assembly and scattering as well as fibrosis and angiogenesis in damaged tissue; known to have anti-inflammatory effect in endothelial and stromal cells | [103,104] |

| Urokinase plasminogen activator | Potent proteolytic activator of numerous growth factor precursors with pleiotropic effects on ECM remodeling, cell migration, blood vessel and nerve growth | [105,106,107,108] |

| Wnt-family ligands | De/differentiation control and activation of resident stromal or progenitor cells, as well as potent mitogen and activator of proliferation | [109,110,111] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nimiritsky, P.P.; Eremichev, R.Y.; Alexandrushkina, N.A.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Tkachuk, V.A.; Makarevich, P.I. Unveiling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells’ Organizing Function in Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040823

Nimiritsky PP, Eremichev RY, Alexandrushkina NA, Efimenko AY, Tkachuk VA, Makarevich PI. Unveiling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells’ Organizing Function in Regeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(4):823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040823

Chicago/Turabian StyleNimiritsky, Peter P., Roman Yu. Eremichev, Natalya A. Alexandrushkina, Anastasia Yu. Efimenko, Vsevolod A. Tkachuk, and Pavel I. Makarevich. 2019. "Unveiling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells’ Organizing Function in Regeneration" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 4: 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040823

APA StyleNimiritsky, P. P., Eremichev, R. Y., Alexandrushkina, N. A., Efimenko, A. Y., Tkachuk, V. A., & Makarevich, P. I. (2019). Unveiling Mesenchymal Stromal Cells’ Organizing Function in Regeneration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(4), 823. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040823