1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are an important reason for death in the world which hinder sustainable development of human beings [

1]. In China, CVDs were also the leading cause of death due to lifestyle changes, urbanization, and the accelerated process of aging, and the figures have exceeded 42% of all deaths in both rural and urban regions, which was much higher than deaths caused by cancer or any other diseases in 2014 [

2]. Traditional Chinese medicine has been used for more than 2000 years and has displayed the explicit role in preventing and treating CVDs, although the detailed pharmacological mechanisms have seldomly been clarified [

3].

Centranthera grandiflora Benth, also known as broad bean

Ganoderma lucidum, wild broad bean root, Huaxuedan, Golden Cat’s Head, and Xiaohongyao, is a medicinal plant widely used for preventing and treating CVDs among Miao Nationality of Yunnan in China. In taxonomy, it belongs to the Centranthera, Scrophulariaceae family. Distinguished as a rare and endangered medicinal plant,

C. grandiflora Benth usually grows well with

Cyperus rotundus and is mainly distributed in Yunnan, Guizhou, and Guangxi in China as well as parts of India, Myanmar, and Vietnam [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Its roots possess many functions, such as to promote blood circulation, to regulate menstruation, to dispel blood stasis, and to relieve pain, and has known coagulation, antibacterial, and anticancer properties [

6,

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, it is mainly used to treat amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, metrorrhagia, fall-related injuries, rheumatic bone pain, traumatic hemorrhage, and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [

6,

8,

9,

10].

So far, studies on this herb have mainly focused on the isolation and identification of its chemical constituents and pharmacological effects, while the discovery of genes related to biosynthesis of active secondary metabolites has not been reported. Azafrin and D-mannitol were first isolated and identified from the roots of

C. grandiflora Benth in 1984 [

8]. Then, aeginetin and azalea were isolated from the roots of

C. grandiflora Benth, and their coagulation, antimicrobial, and anticancer functions were verified in 2012 [

10]. In the same year, nine iridoid glycosides including aucubin, mussaenoside, 8-epiloganin, 8-epiloganic acid, mussaenosidic acid, catalpol, gardoside methyl ester, geniposidic acid, and 6-O-methylaucubin were isolated from roots of

C. grandiflora Benth [

6]. In 2014, another 17 compounds, including six new ones: centrantheroside A to E and neomelasmoside; phenylethanoid glycosides: plantainoside A, calceolarioside A, acteoside, and isoacteoside; monoterpenoid glycosides: melasmoside and rehmaionoside C; Di-O-methylcrenatin; azafrin; β-sitosterol; mannitol; and β-daucosterol were isolated from

C. grandiflora Benth roots [

5,

7]. Studies have shown that iridoid glycosides, phenylethanoid glycosides, and azafrin are the main substance bases for their pharmacodynamics [

5,

7]. In 2017, tissue culture of

C. grandiflora Benth was also successfully developed [

11].

At present,

C. grandiflora Benth roots sold in public markets are mainly collected from wild resources, while its artificial cultivation has just started [

5]. So far, the cost of annual

C. grandiflora Benth planting is about

$0.13 million per hectare and the worth of annual yield is about

$0.64 million per hectare [

5]. Therefore, to explore the biosynthetic pathways and regulatory mechanisms of the main active ingredients of

C. grandiflora Benth will lay a scientific foundation for breeding new varieties of this herb and for producing its medicinal chemical constituents by synthetic biology.

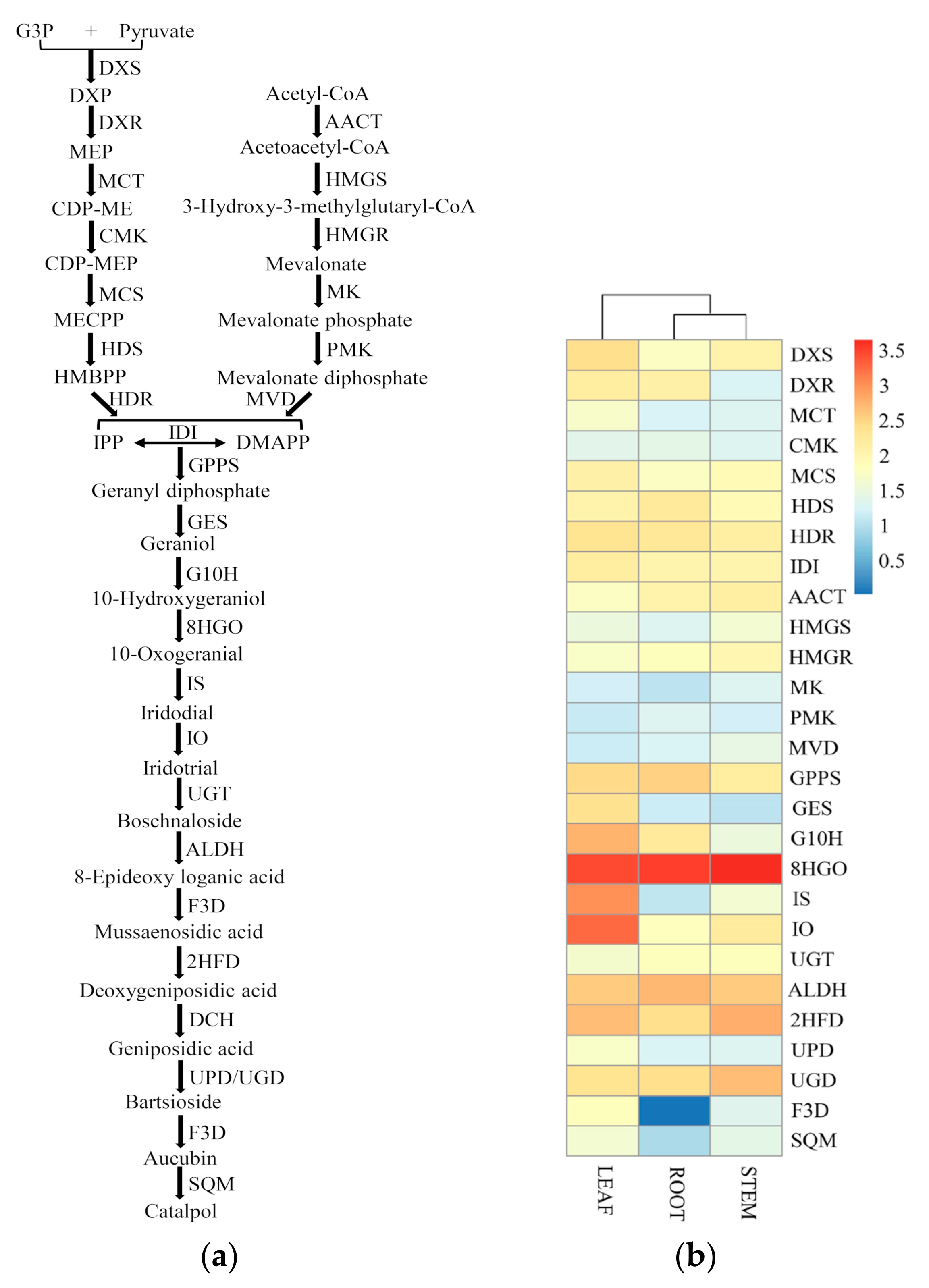

Iridoid glycosides belong to monoterpenoids, and their biosynthesis in plants can be divided into three stages. The first stage is precursor formation, which includes the plastidial 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-4-phosphate (MEP) pathway and the cytoplasmic mevalonate (MVA) pathway to produce isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) [

12,

13]. The second stage is the formation of a carbon skeleton structure [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The third stage is the post-modification of terpenoids: hydroxylation, methylation, isomerization, demethylation, glycosylation, etc. [

16]. So far, most of the biosynthesis pathways of iridoid glycosides remain unclear. However, the complete catalpol biosynthetic pathway was first elicited in

Picrorhiza kurroa [

17], and it was partially decoded in

Rehmannia glutinosa [

18]. In

P. kurroa, the catalpol biosynthetic pathway contains 29 steps including 14 steps for the MEP and MVA pathways and 15 steps for the iridoid pathway [

17]. As the MEP and MVA pathways has been widely and intensively studied and they are conserved in plants [

19], here, we mainly focused on the iridoid pathway. So far, two iridoid pathways including secoiridoid pathway (Route I) and decarboxylated iridoid pathway (Route II) have been reported, and the early enzymatic steps containing geranyl diphosphate synthase (GPPS), geraniol synthase (GES), geraniol 10-hydroxylase (G10H), 8-hydroxygeraniol oxidoreductase (8HGO), iridoid synthase (IS), iridoid oxidase (IO), and UDP-glucosyltransferase (UGT) are common to both pathways [

20], has been verified in

Catharanthus roseus and

P. kurroa [

14,

21,

22], and proposed in

Gardenia jasminoides [

23,

24]. The remaining steps were first deduced by chemical intermediates [

20], and then the corresponding enzymes were predicted and discovered by transcriptome analysis [

17]. In

P. kurroa, another seven enzymes containing aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALD), flavanone 3-dioxygenase/hydoxylase (F3D), 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase (2FHD), deacetoxycephalosporin-C hydroxylase (DCH), uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase/UDP-glucuronic acid decarboxylase (UPD/UGD), and squalene monooxygenase (SQM) have been proposed to catalyze the remaining seven steps in catalpol biosynthesis [

17].

Acteoside, belonging to phenylethanoid glycosides, is composed of two parts: caffeoyl CoA and hydroxytyrosol glucoside [

25]. Feeding and inhibition experiments showed that hydroxytyrosol glucoside moiety is derived from tyrosine while caffeoyl CoA moiety is derived from phenylalanine via the cinnamate pathway and that both tyrosine and phenylalanine come from the shikimate pathway [

26,

27]. In

Ole europae and

R.

glutinosa, phenylalanine is converted into caffeoyl CoA via four enzymes including phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H), coumarate-3-hydroxylase (C3H), and 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) [

18,

25,

28]. Simultaneously, tyrosine is transformed into hydroxytyrosol glucoside through two alternative pathways: one is via

L-dopa, dopamine, and hydroxytyrosol with the enzymes polyphenol oxidase (PPO), tyrosine decarboxylase (TDC), copper-containing amine oxidase (CuAO), alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and UGT; the other is via tyramine, tyrosol, and salidroside with the enzymes TDC, CuAO, ADH, UGT, and PPO [

18,

25,

28]. Finally, caffeoyl CoA and hydroxytyrosol glucoside can be converted into acteoside by Shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (HCT) and UGT [

18,

25]. Recent studies have verified that acteoside possesses pharmacological properties: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, antitumor, antidiabetes, and hepatoprotection [

29,

30,

31,

32].

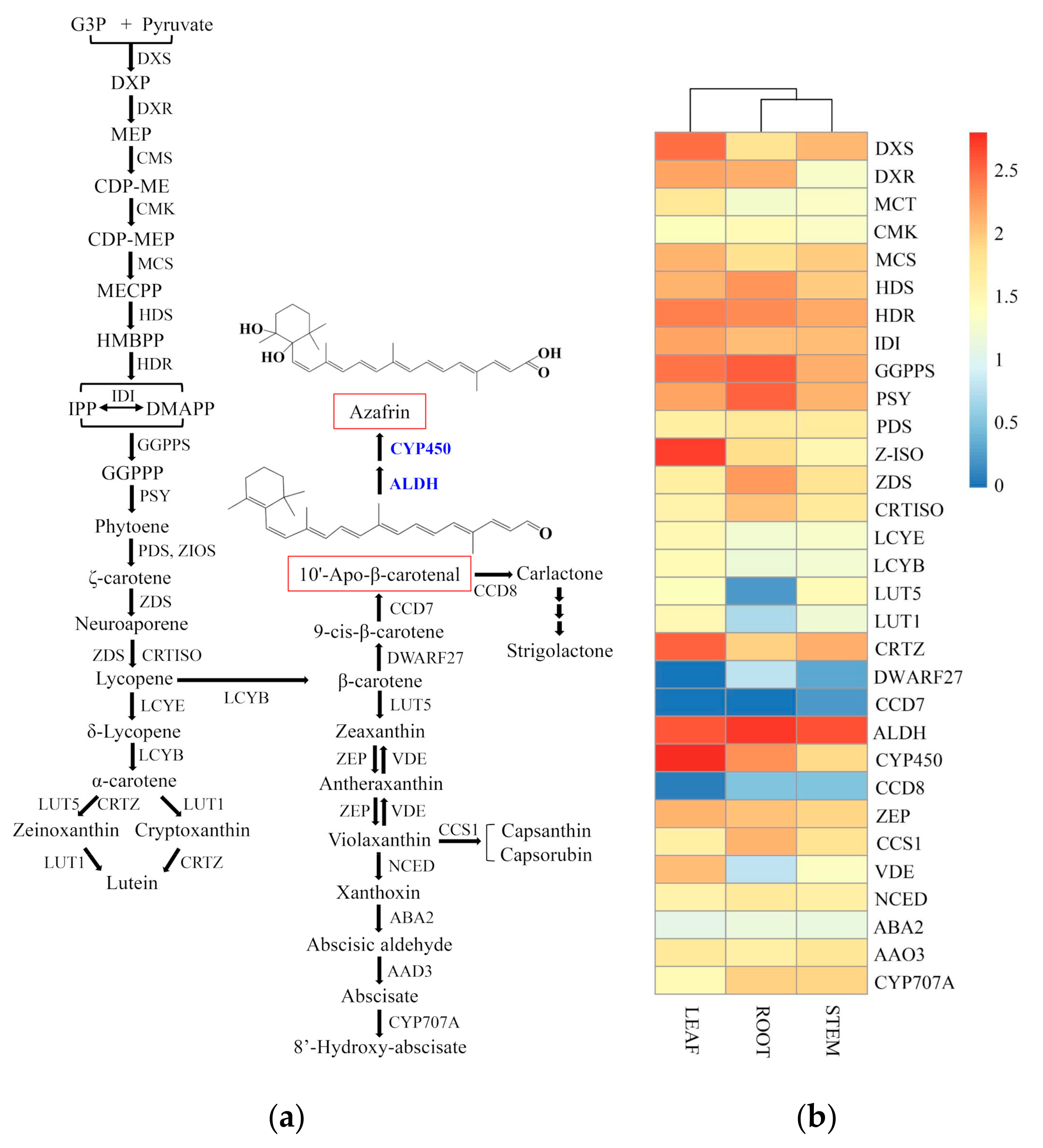

Azafrin, belonging to carotenoid derivative, is one of the most abundant active ingredients in

C. grandiflora Benth roots and plays an important role in myocardial protection [

33]. Carotenoids are ubiquitous pigments in plants, and they confer plants with bright yellows, oranges, and reds [

34]. In higher plants, carotenoids are synthesized through isoprene-like pathways in plastids, including condensation, dehydrogenation, cyclization, hydroxylation, and epoxidation reactions, while lycopene acts as an important branch point of both synthesis of α-carotene and β-carotene [

35]. In the α-carotene pathway, α-carotene is synthesized by lycopene ε-cyclase (LCY-ε) and lycopene β-cyclase (LCY-β) and is then converted to lutein by ε-hydroxylase (LUT1) and β-cyclohexylase (LUT5) [

17,

18]. In the β-carotene pathway, LCY-β catalyzes the synthesis of β-carotene, which can be converted into strigolactone, astaxanthin, capsanthin, capsorubin, and violaxanthin under the catalysis of different enzymes, while violaxanthin can be further converted into abscisic acid [

36,

37]. However, studies have shown that azafrin is an apocarotenoid which is generated by cleavage of carotenoids at the C9′–C10′ [

38,

39]. In the strigolactone pathway, β-carotene is converted into carlactone through 9-cis-carotene, 10′-apo-β-carotenal by enzymes DWARF27, carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 7 (CCD7), and CCD8 [

39]. The intermediate product 10′-apo-β-carotenal is very similar to azafrin in structure except one terminal carboxyl group and two hydroxyl groups. Therefore, the hypothesis that azafrin is synthesized via 10′-apo-β-carotenal is proposed in this article.

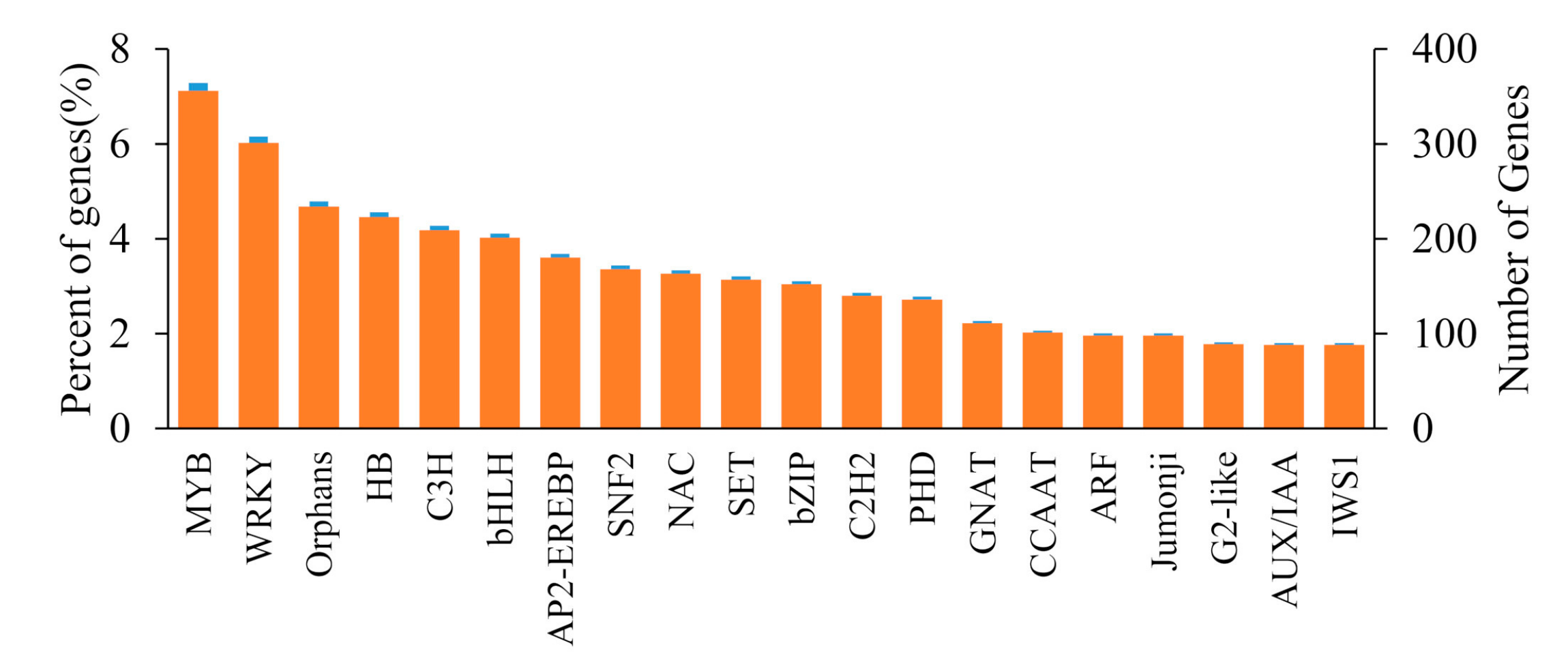

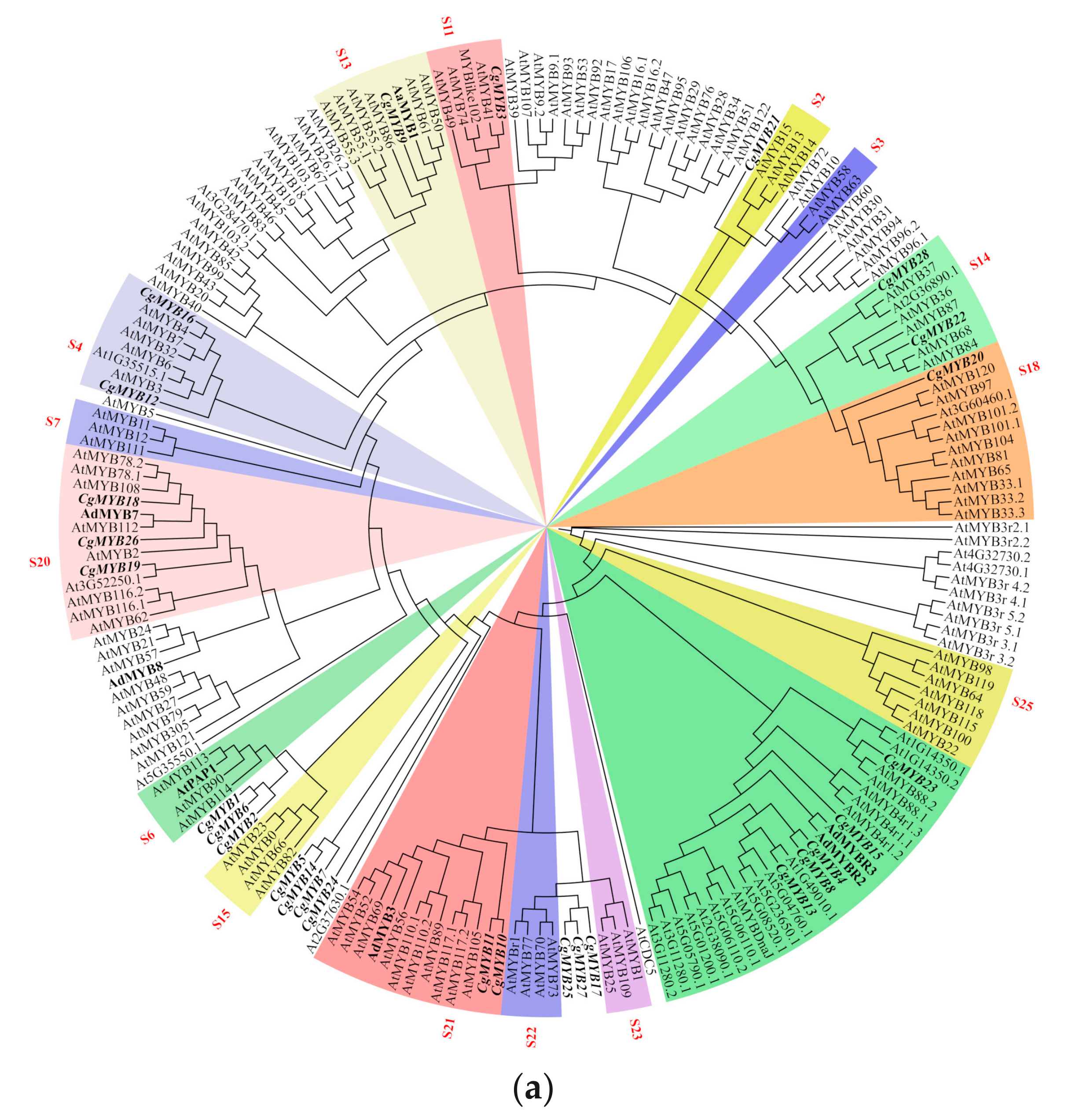

Thus, the aim of this research is to characterize globally for the first time the transcriptomes of the root, stem, and leaf of C. grandiflora Benth using the Illumina Hiseq2000. To explore the genes involved in the catalpol, acteoside, and azafrin biosynthesis pathways and regulatory mechanisms, transcripts from leaves, stems, and roots of C. grandiflora Benth were screened out, quantified, and annotated. The results obtained here will facilitate further molecular studies in C. grandiflora Benth.

3. Discussion

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) remain a major cause of health loss for all regions of the world in the past 25 years [

70]. In China, the incidence of CVDs is continuously rising and will keep an upward trend in the next decade [

2]. Therefore, to find the herbs with effective treatment of CVDs is imminent.

C. grandiflora Benth is one of the most precious herbs in the area of Miao Nationality in Yunnan, China. It is widely used in folk medicine because of its multifunctional medicinal values, especially in the aspect of the prevention and treatment of CVDs [

7]. Although it has been collected in the Chinese Materia Medica, up to now, it has not been included in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia because of limited researches [

9]. The current situation is high market prices and overexploitation of wild resources, which has not only prevented the herbal medicine from being widely used but has destroyed species diversity. Synthetic biology will provide solutions for the abovementioned problems through the biosynthetic pathway elucidations of the main pharmacodynamic components.

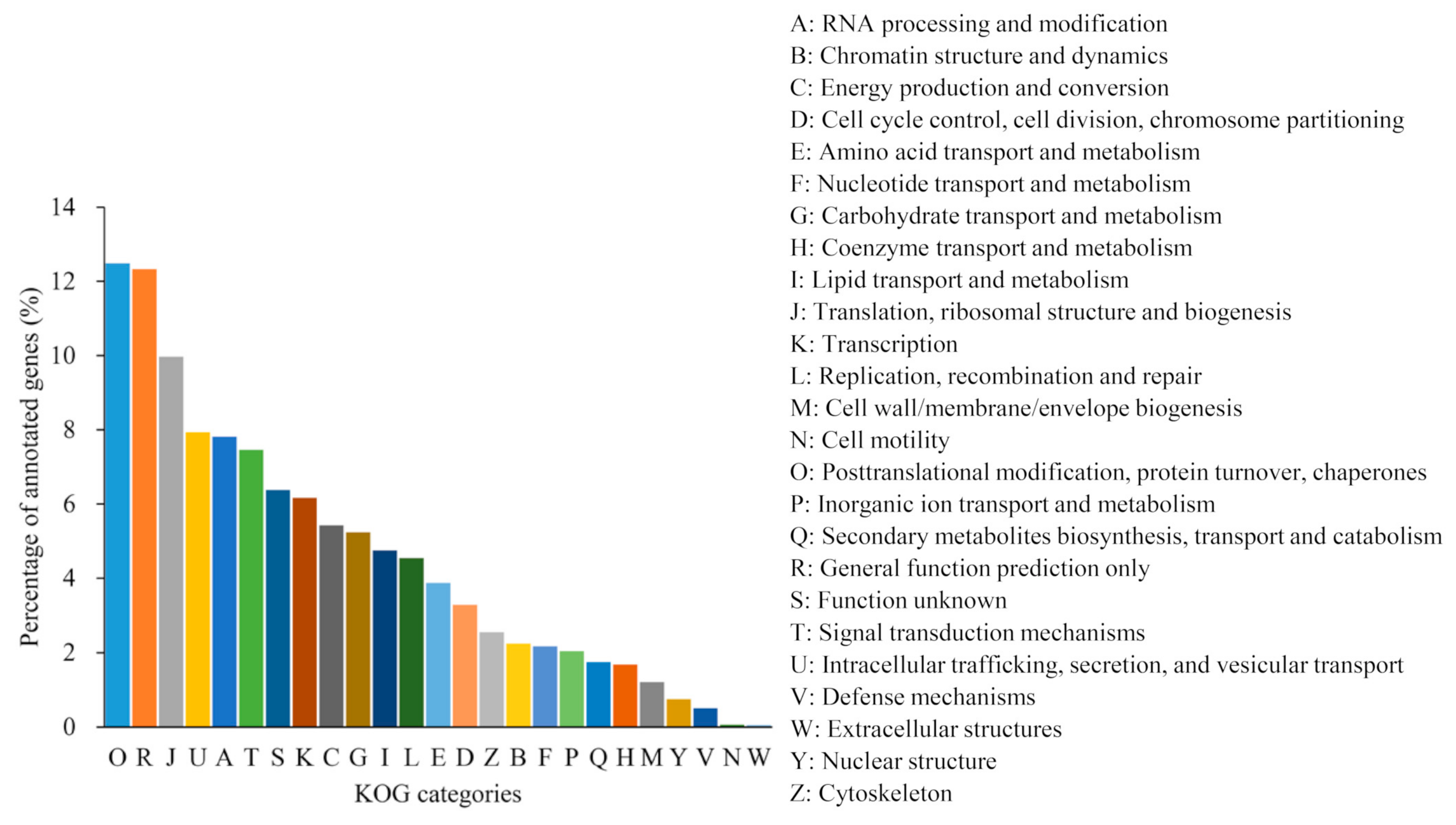

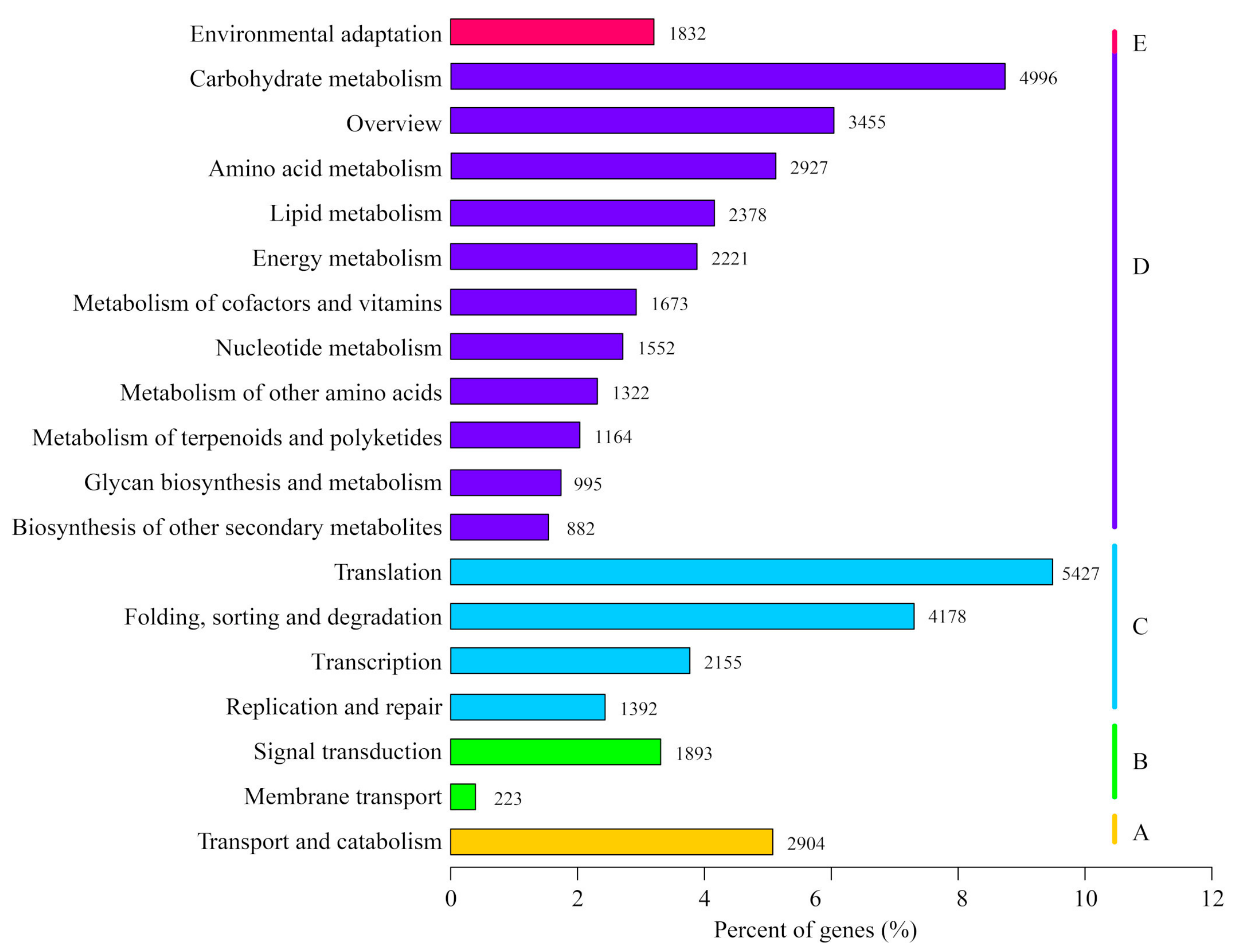

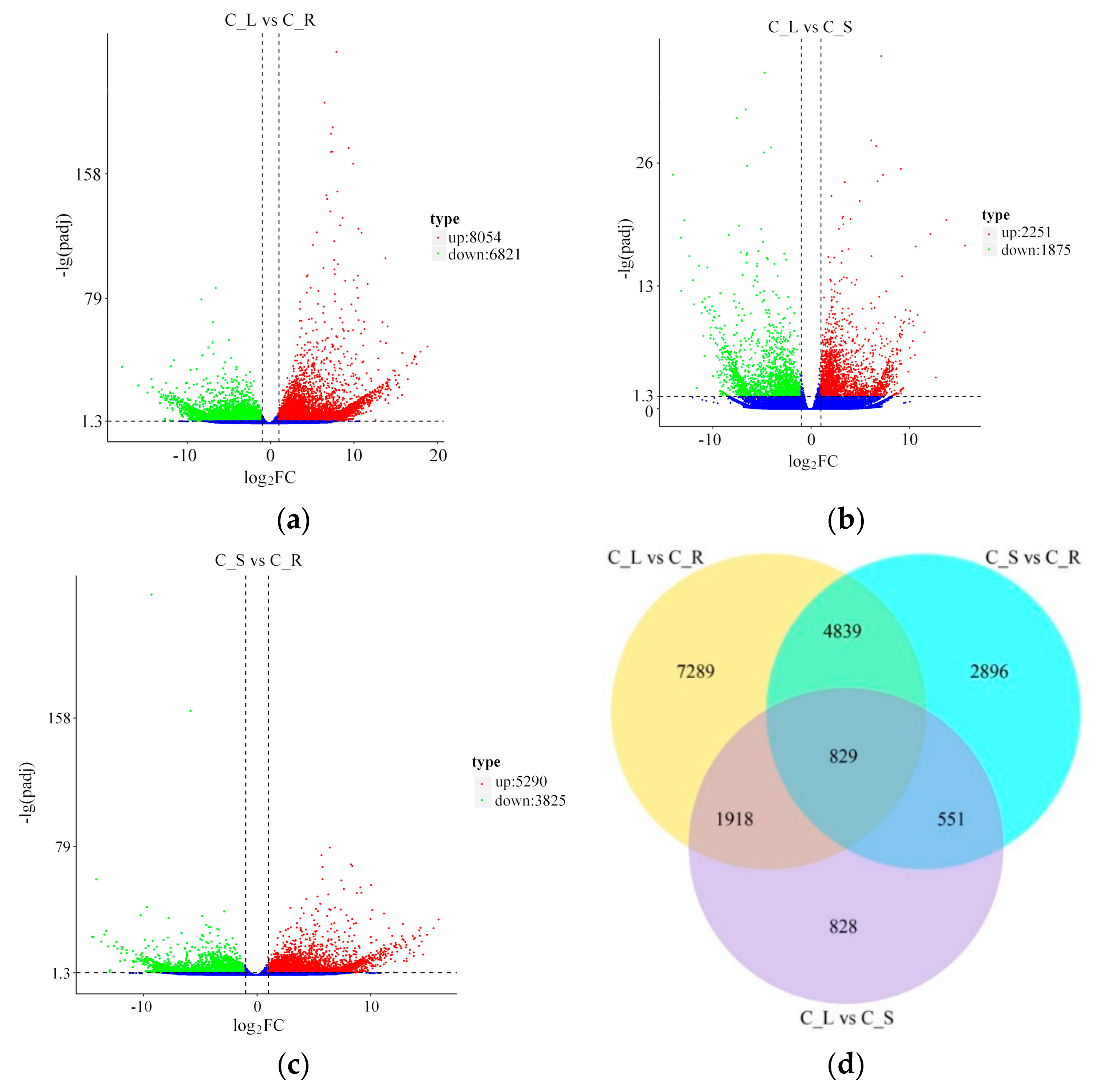

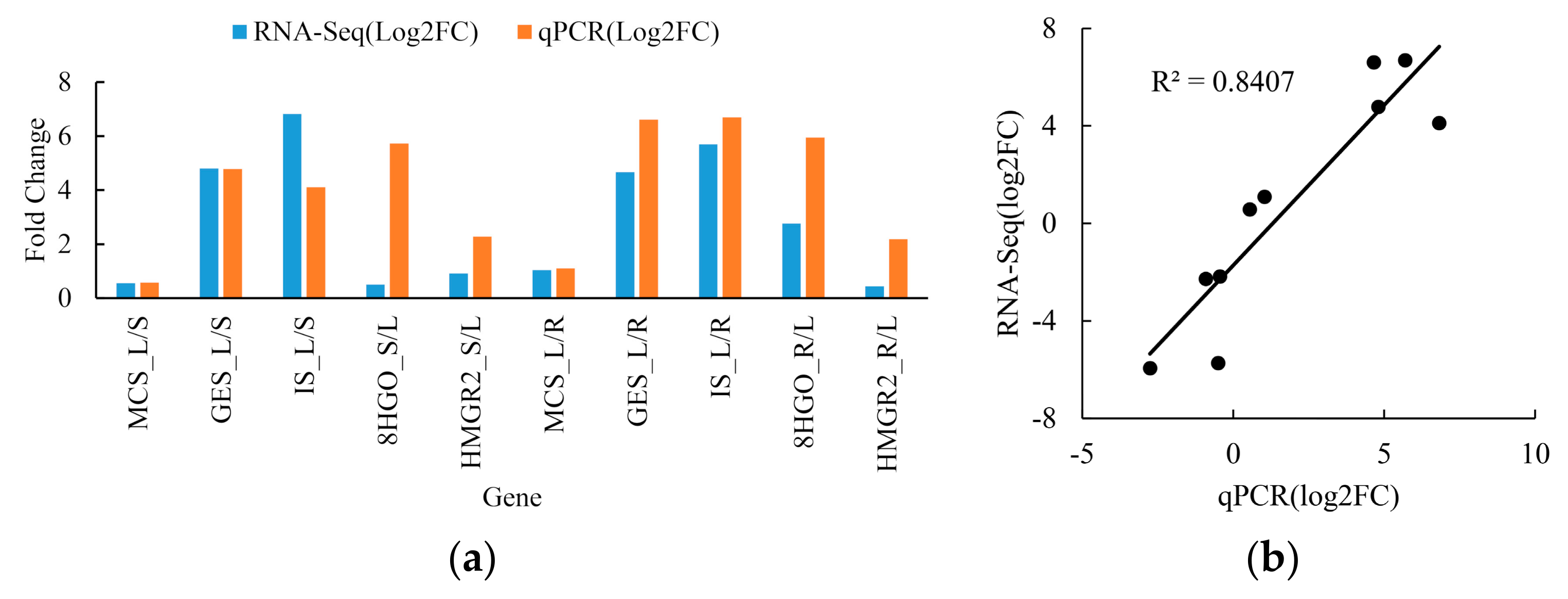

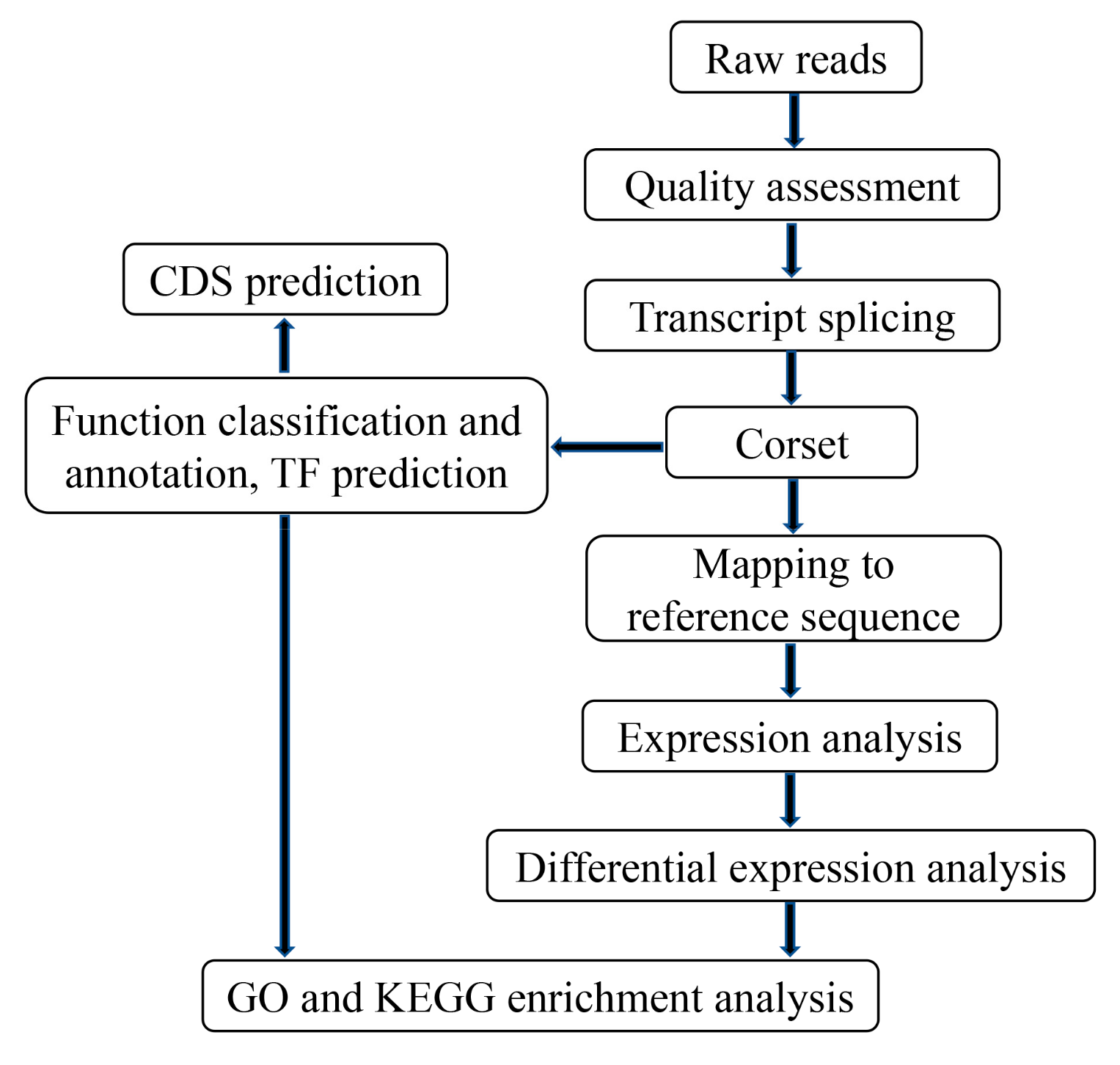

So far, de novo transcriptome analysis is an important method in gene discovery of biosynthesis pathways, especially for species without reference genomes [

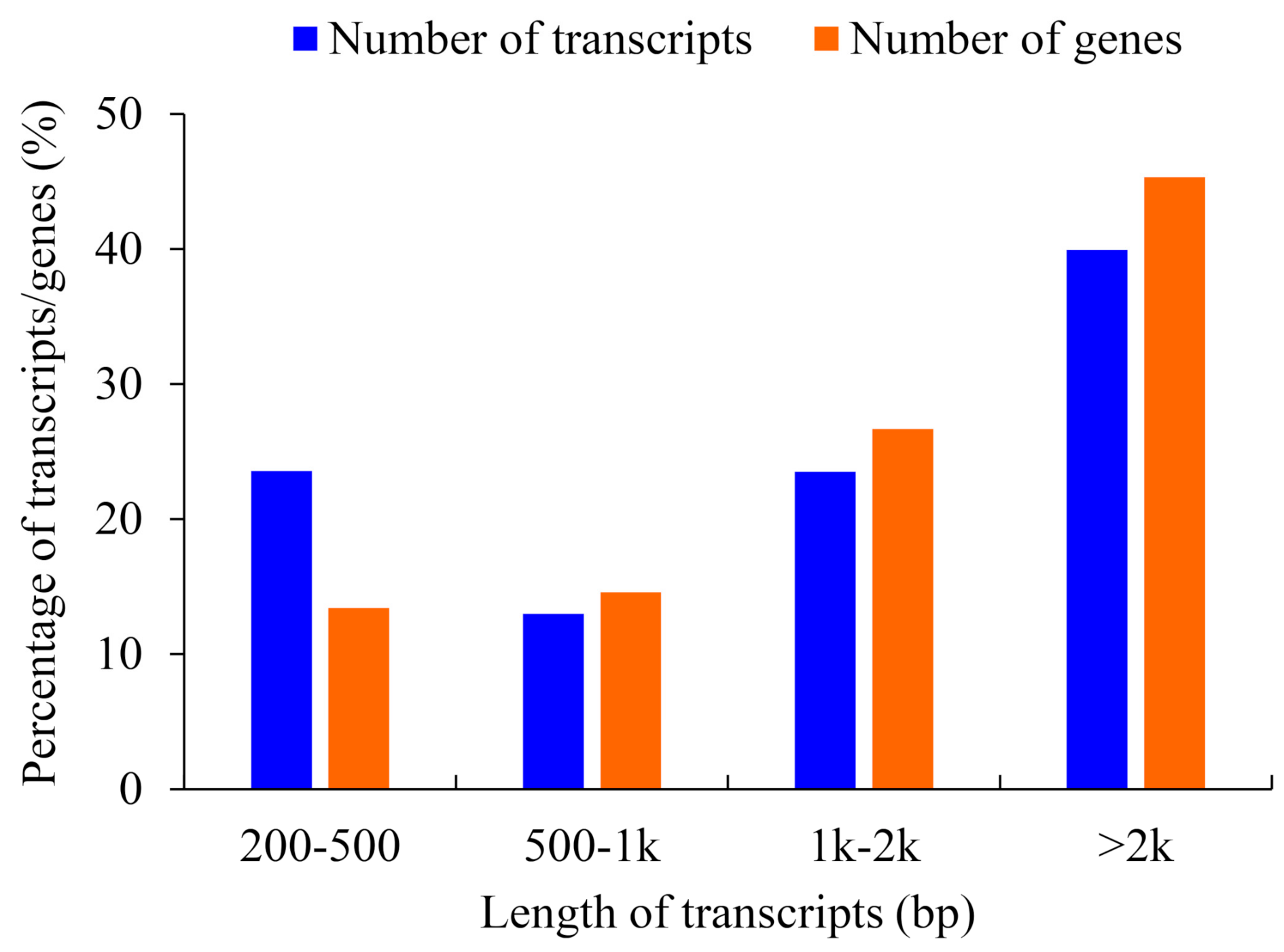

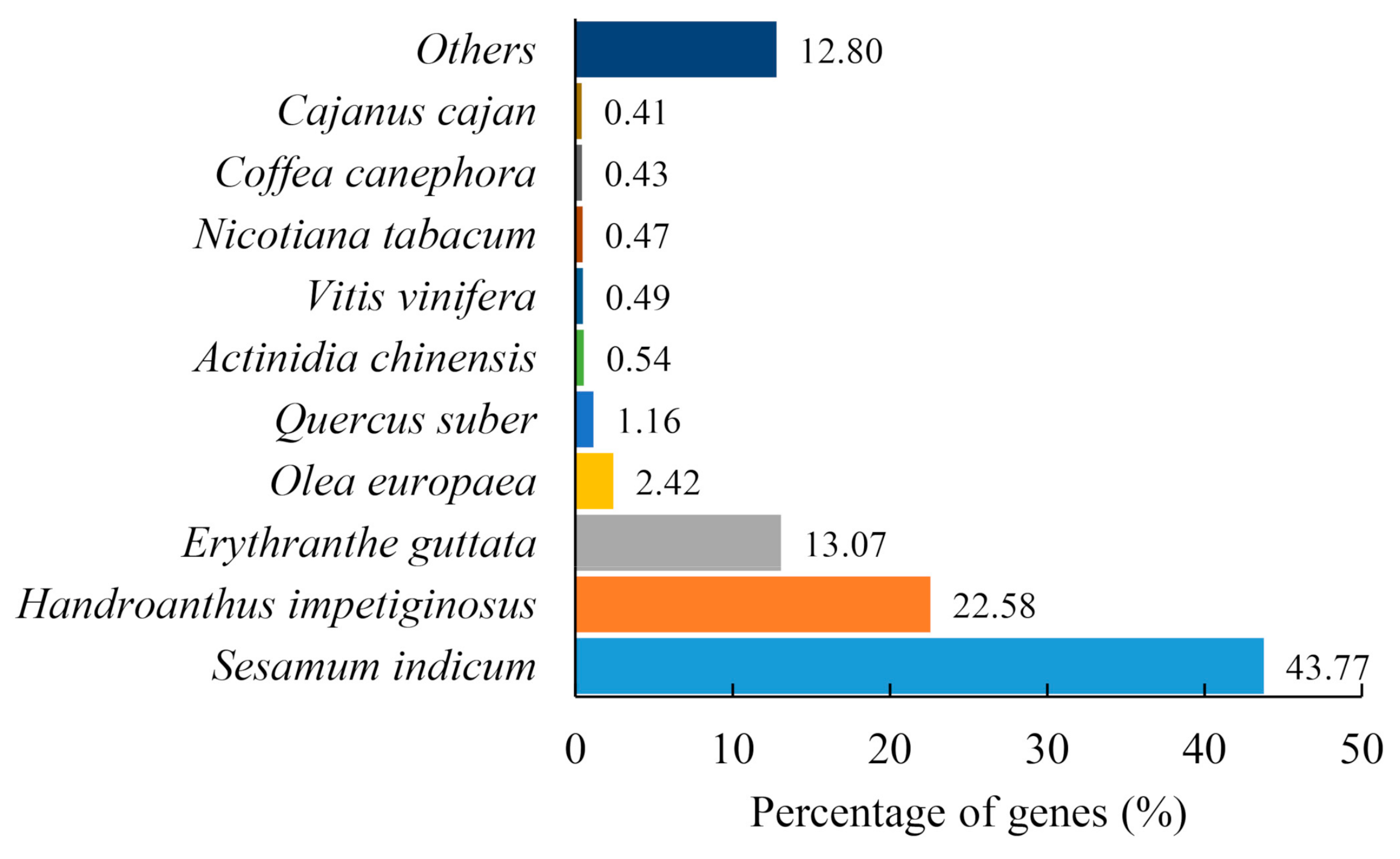

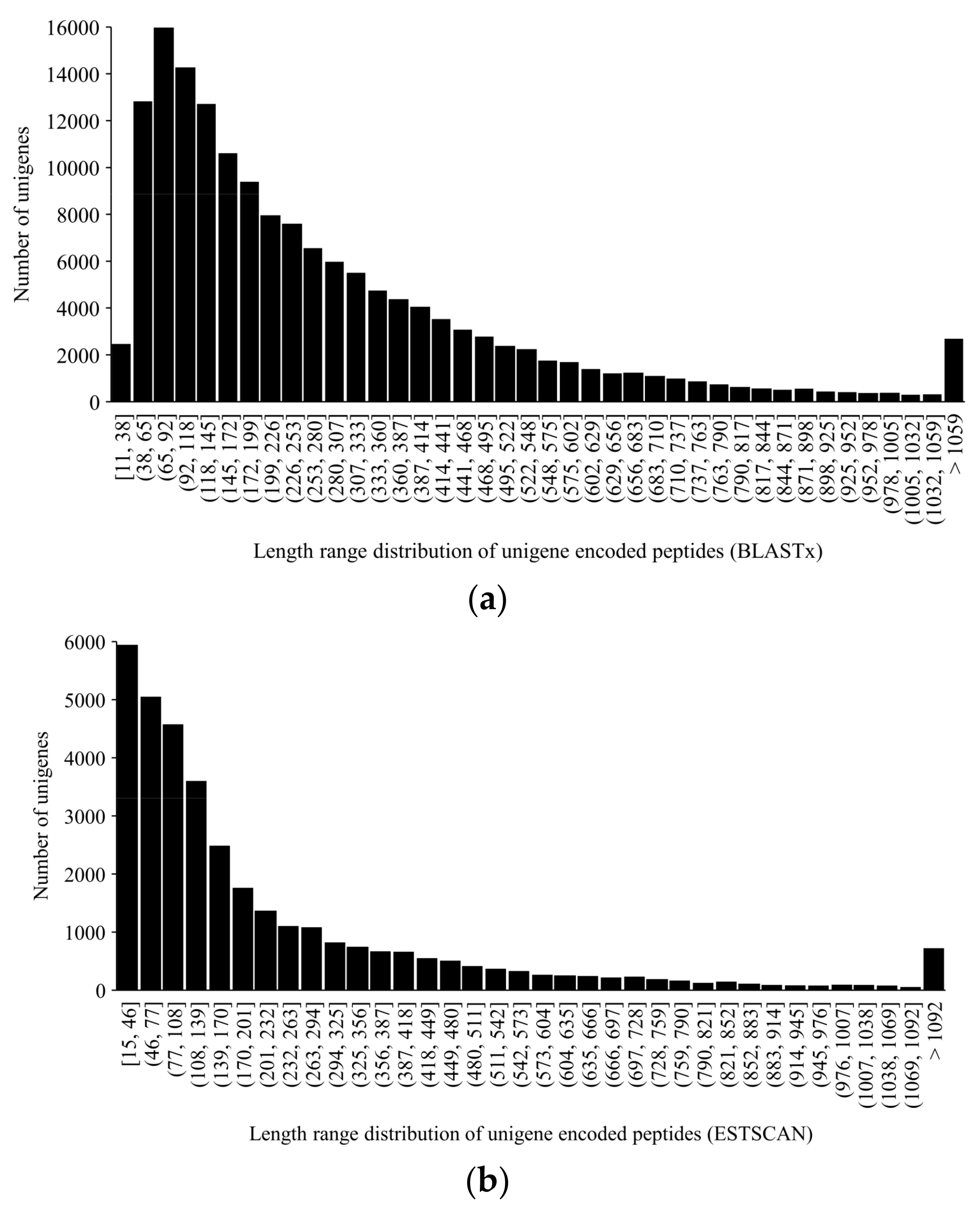

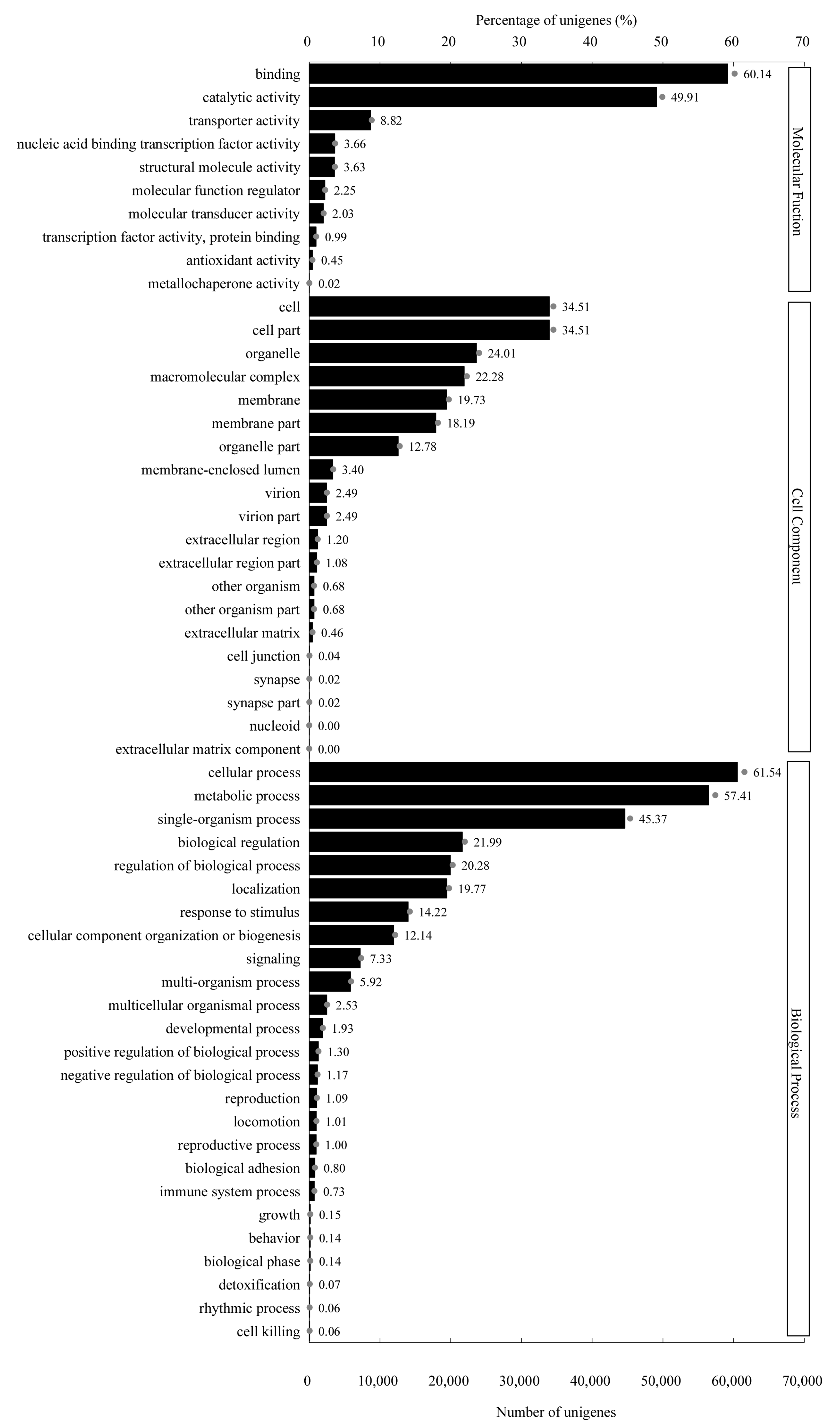

13]. In this research, the transcriptomes of three tissues with three biological repeats were sequenced by illumine Hiseq2000, and 438,112,930 clean reads were assembled into 173,851 transcripts and 153,198 unigenes. This suggests that one gene may have different transcripts which may come from variable splicing, alleles, different copies of the same gene, homologs, orthologs, etc. The mean length of transcripts and genes were 1895 bp and 2115 bp, respectively, and the N50 of the transcripts and genes were 2902 and 2936 bp, respectively (

Table 2), which were higher than that in

Dendrobium huoshanense,

Persea Americana, and

R. glutinosa [

18,

71,

72]. These results implied that our assembly quality was suitable for subsequent analyses. In the species distribution analysis of unigenes, more than 43.77% of unigenes were matched to

Sesamum indicum (

Figure 2), which is similar to

R. glutinosa, a plant of Scrophulariaceae; these results implied that they shared the closer genetic relationship, similar chemical substances, and similar biosynthetic pathways. Catalpol, acteoside, and azafrin are three medicinal ingredients in

C.

grandiflora Benth; however, their biosynthetic pathway is unexplored.

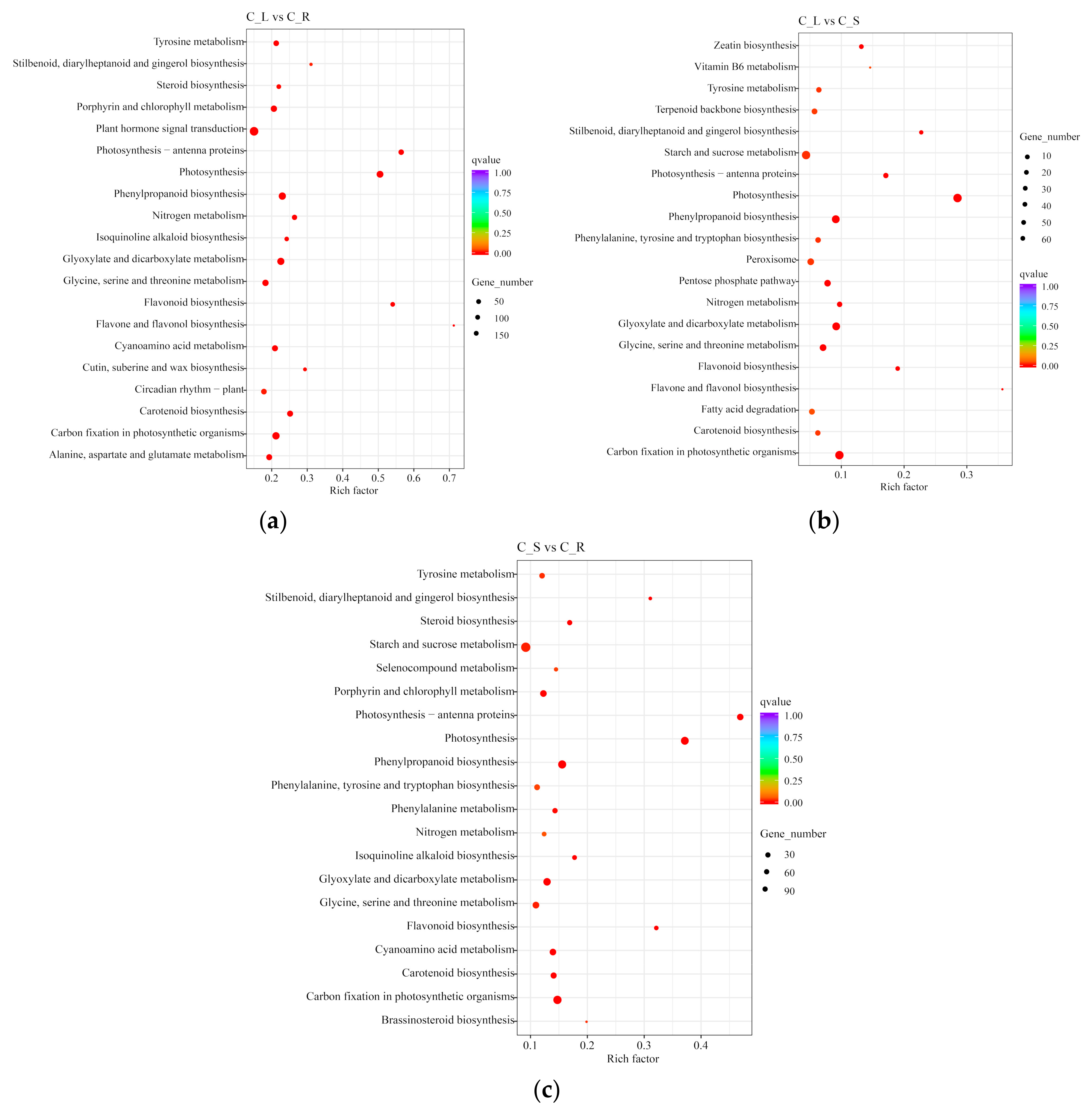

So far, catalpol biosynthesis containing terpenoid backbone pathway and iridoid pathway has not been fully deciphered due to the deficiency of detailed information on genetic and molecular levels [

20]. In 1993, Damtoft found that 8-epi-deoxyloganic acid, bartsioside, and aucubin are intermediates of catalpol biosynthesis by feeding experiments [

48]. Then, Jensen et al. confirmed that catalpol is synthesized via decarboxylated iridoids pathway (Route II), which involved 8-epi-iridodial, 8-epi-iridotrial, and 8-epi-deoxyloganic acid [

73]. In 2013, the more detailed route II was proposed in

R. glutinosa and

P. kurrooa [

21,

41]. In 2015, the complete catalpol biosynthesis pathway was hypothesized in

P. kurrooa according to data of the transcriptome mining, gene expression, and picroside content [

17]. In our transcriptomes, 368 unigenes were annotated to the catalpol biosynthetic pathway with 60 unigenes upregulated in leaves and 39 unigenes in roots; simultaneously combined with the fact that

F3D gene was not expressed in roots, we deduced that catalpol biosynthesis was mainly active in leaves. A recent article showed that, in wild

C. grandiflora Benth, the content of catalpol is far higher in leaves than in stems and roots [

74], which also implied that catalpol is mainly synthesized in leaves other than roots. The discovery of rate-limiting enzymes is essential for synthetic biology; therefore, some genes are discussed here. Catalpol biosynthesis begins with the terpenoid backbone pathway, which contains the MEP and MVA pathways. In the MEP pathway, the DXS enzyme is the first and rate-limiting enzyme, and in

A. annua, among the three AaDXSs, only AaDXS2 might participate in artemisinin biosynthesis [

75]. Contrary to

A. annua, the

DXSs were more abundant in our transcriptome, which seems that DXS was not a limiting enzyme in

C. grandiflora Benth. Further studies are needed to clarify which DXS functions in MEP pathway. A recent report showed that plastidial IDI plays an important role in optimizing the ratio between IPP and DMADP as precursors for different downstream isoprenoid pathways while mutation of

IDI1 reduced the content of carotenoids in fruits, flowers, and cotyledons (except mature leaves) [

44]. In our transcriptome, there were 28

IDI genes with two upregulated in leaves compared with roots, which highlights their importance in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (

Table 4). However, there were no significant differences for the overall expression of

IDI genes in roots, stems, and leaves in our transcriptome (

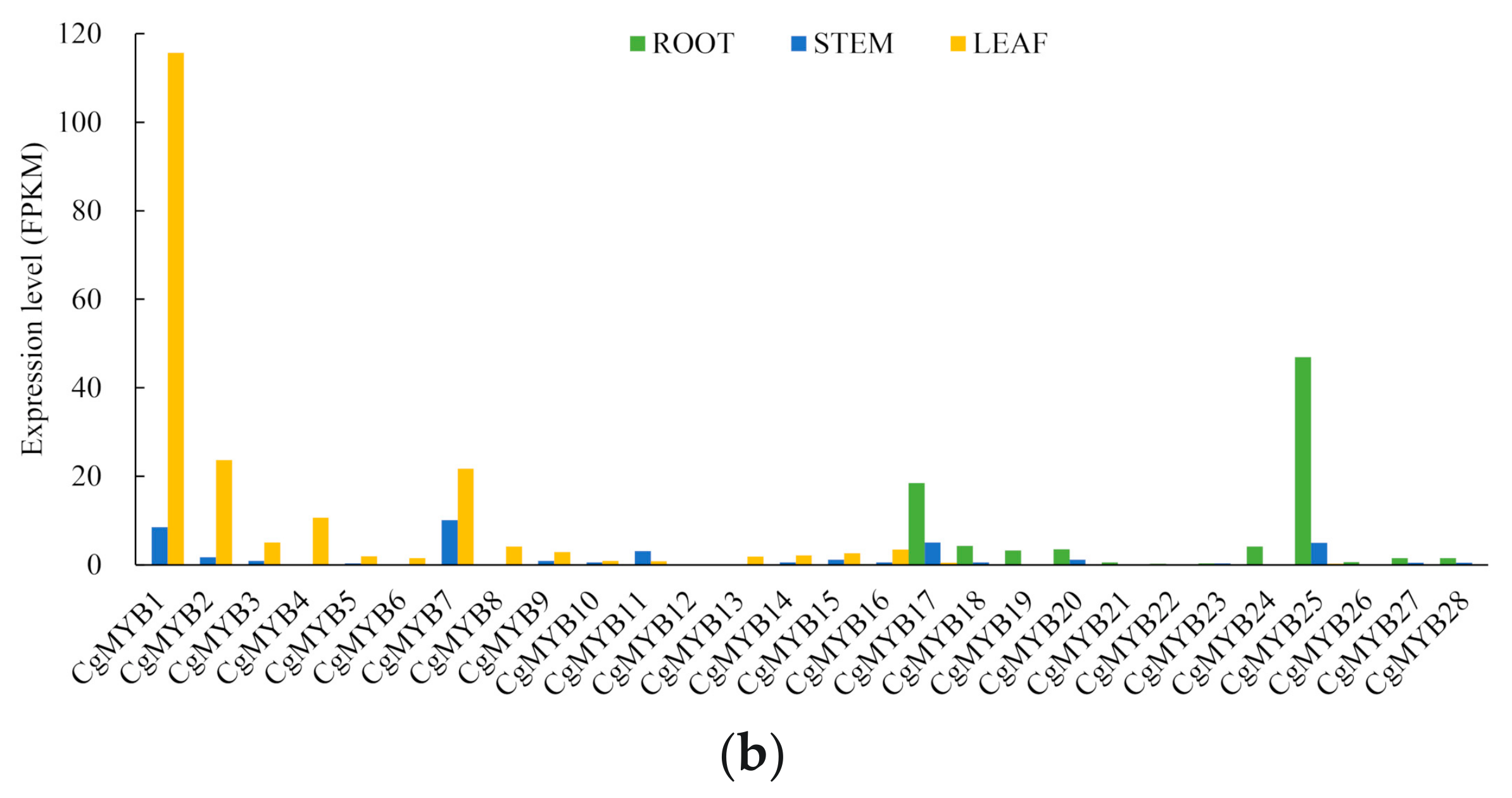

Figure 9b). What is interesting is that there was only one

MCS gene in our transcriptome; however, its expression levels in roots, stems, and leaves were all relatively high, which directly denied that

MCS was a rate-limiting enzyme gene. According to the expression profile,

MCT may be a rate-limiting enzyme for roots (

Figure 9b). In addition, the relative contribution of the MEP and MVA pathways for a specific pathway is a focus scientist paying attention to. In

P. kurroa, the biosynthesis of picroside-I is contributed solely by the MEP pathway [

17]. In

Taxus baccata, the MEP pathway provides the main source of universal terpenoid precursor IPP [

76]. However, in

C. grandiflora Benth, the contribution of the MEP and MVA pathways for catalpol biosynthesis remains to be clarified and it will be resolved by the inhibition experiments in the future.

Acteoside biosynthesis was first studies in an

O. europaea cell with feeding experiments, which outline the basic pathway profile: caffeoyl moiety was synthesized through the phenylalanine-derived pathway including intermediates cinnamic acid, p-coumaric acid, and caffeic acid, while hydroxytyrosol moiety was formed via the tyrosine-derived pathway including two alternative routes [

26]. Then, HCT enzyme which connects the caffeoyl moiety and the hydroxytyrosol moiety, UGT enzymes, and the corresponding enzymes of the phenylalanine-derived pathway and tyrosine-derived pathway were hypothesized in

R. glutinosa [

28]. All of the acteoside pathway genes were found in our transcriptome of

C. grandiflora Benth. Expression profiles showed that genes involved in both the phenylalanine-derived pathway and the tyrosine-derived pathway were more abundant in leaves and stems compared to roots, especially for the

PAL and

PPO genes (

Figure 10b). This is consistent with the reports that, in

Harpagophytum procumbens, the content of acteoside was higher in leaves and stems than in roots and that, in

Sesamum indicum, the content of acteoside in leaves is far higher than in stems and roots [

25,

77].

Studies have shown that PAL is an entry-point enzyme which can convert

L-Phe into trans-cinnamic acid and that it plays a vital role in channeling carbon flux from primary metabolism into the phenylpropanoid pathway [

78]. So far,

PAL gene has been cloned from many medicinal plants, such as

Ocimum basilicum [

79],

Ginkgo biloba [

80],

Salvia miltiorrhiza [

81], and

A. annua [

82]. In

G. biloba, the highest expression of

GbPAL gene was found in leaves, followed by stems, and the lowest expression was in roots; transcription levels of

GbPAL were closely related to flavonoid accumulation [

80]. In

R. glutinosa, the

RgPAL gene (CL1389.Contig1) shared the same expression pattern as in

G. biloba [

28]. In

A. annua, the highest expression of the

AaPAL gene was found in young leaves and the lowest expression of that was in roots [

82]. In plants,

PAL gene is a multi-gene family and the gene number ranges from 4 in

A. thaliana to more than 12 in tomato and potato [

83]. For example, there are 6

PAL genes in

R. glutinosa [

28]. Recently, three different redundancy phenomena including active compensation in ligand plus passive compensation in receptor in tomato, passive compensation in ligand plus active compensation in receptor in Arabidopsis, and active compensation in both in corn have been figured out [

84]; however, which type does the

CgPAL genes belong to and whether they benefit the plants themselves in

C. grandiflora Benth remain to be discovered. Unlike potato, the

PAL gene family is highly redundant but underutilized due to the highly silencing mechanism in tomato [

83]. In our transcriptome, there are 19

PAL genes and their highest expressions are found in leaves and stems with the lowest expression in roots (

Figure 10b), which is similar to that in

G. biloba,

R. glutinosa, and

A. annua [

28,

80,

82]. Our transcriptome profiling data showed that 10 of 19

CgPAL genes were not expressed or slightly expressed in roots, stems, and leaves (

Figure S1), which implied that gene silencing was also active in

C. grandiflora Benth, and DNA cytosine methylation may account for this phenomenon [

83]. A recent report showed that functional redundancy among

BZR/BEH (

BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT/

BRI1-EMS-SUPRESSOR1/BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 HOMOLOG) gene family members is not necessary for trait robustness [

85]. Even in tomato, only

PAL5 was expressed under environmental stimuli [

83]. Therefore,

PAL genes including the 3 significantly upregulated and 1 significantly downregulated in leaf vs. root in

C. grandiflora Benth played important roles in acteoside biosynthesis (

Table 5).

Polyphenol oxidase is usually undesirable in fruit and vegetable due to the browning, while it is desirable in tea, coffee, cocoa, etc. for the pigmentation [

86]. Polyphenol oxidase (1,2-benzenediol: oxygen oxidoreductase), also known as tyrosinase, catechol oxidase, and laccase according to the specific substrate and reaction mechanism, is a group of copper-containing proteins [

86,

87]. A typical PPO protein contains three conservative regions: an N-terminal transit peptide that is responsible for the import of PPO into the thylakoid lumen; a di-copper center, each with three histidine residues to bind a copper atom; and a C-terminal region [

88]. Polyphenol oxidases can catalyze two quite different types of reactions: monophenol monooxygenases (E.C. 1.14.18.1) activity and o-diphenol oxidation reactions including catechol oxidases (E.C. 1.10.3.1) and laccases (E.C. 1.10.3.2) activity [

87]. In plants, polyphenol oxidase is localized in chloroplasts and the reaction product accumulated in thylakoid [

89]. The number of

PPO gene ranges from 1 to 13 in land plants with 0 for green algae and

A. thaliana, and tandem duplications of the

PPO gene family is common in dicotyledon [

88]. In our transcriptome, 11

PPO genes were clustered into three groups. Expression levels of the upper group including

PPO7,

PPO9,

PPO10, and

PPO11 were higher in leaves and stems compared with roots, while that of the bottom group including

PPO1,

PPO2, and

PPO3 were higher in roots and stems than in leaves with the somewhat low expressions in middle group including

PPO4,

PPO5,

PPO6, and

PPO8 (

Figure S2). Phylogenetic analysis of 11 CgPPOs with 6 PPOs of

Solanum melongena and 6 PPOs of

Solanum lycopersicum showed that all of our CgPPO proteins are clustered into one clade and that the other 12 PPO proteins formed another two clades (

Figure S3). These species-specific PPO clades were also found in four major land plant lineages including

Populus trichocarpa,

Glycine max,

Vitis vinifera, and

Aquilegia coerulea, which implied that

CgPPO genes were also formed by independent burst of gene duplication [

88].

Azafrin (C

27H

38O

4) derivates from tetraterpenoids (C

40). It has been found in many medicinal plants such as rhizome of

Alectra chitrakutensis,

Bergenia ciliate,

Caralluma umbellate, and

Alectra parasitica, and it has the functions of being antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, treatment of cardiovascular diseases [

90,

91,

92,

93]. Roots of

C. grandiflora Benth display orange-yellow color, which is largely due to the presence of abundant azafrin as

A. parasitica [

93]. So far, the biosynthetic pathway of azafrin is not established from perspectives of chemistry and biology. There are studies implying that excentric cleavage of carotenoid compounds is a possible route [

94]. CCD7 can catalyze β-carotene (C

40) into 10′-apo-β-carotenal (C

27) and ionone (C

13) to support the above hypothesis [

39]. In the view of molecular structure, the differences between 10′-apo-β-carotenal and azafrin are one terminal carboxyl group and two hydroxyl groups in cyclohexane skeleton. Therefore, two reactions are indispensable from 10‘-apo-β-carotenal to azafrin: one is to convert the aldehyde group into carboxyl groups, and the other is to insert two oxygen atoms into cyclohexane skeleton to generate two hydroxyl groups. The ALDH superfamily comprises a group of enzymes involved in the NAD

+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide) or NADP

+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate)-dependent conversion of various aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids [

95]. Although there are only 76 NAD

+-dependent

ALDH genes in our transcriptome, they are candidate genes for azafrin biosynthesis. In plant, CYP450s are responsible for many oxidative reactions such as hydroxylation, epoxidation, dealkylation, and dehydration, and the reactions catalyzed by CYP450s are irreversible [

53]. There are 413 CYP450 unigenes in our transcriptome, of which 5 are significantly upregulated (log

2(FC) > 10) and 5 are significantly downregulated in leaf vs. root (

Table 6). They can be candidate genes of azafrin biosynthesis. The key enzymes determine the flux of the pathway, and the expression of the key enzyme gene dominates the number of enzymes. In marigold, the expression level of the

LCYE gene in petals and

LCYB gene in leaves were positively correlated with the lutein content [

96]. In

Momordica cochinchinensis, transcriptional regulation of genes including

HMGR,

HDS,

PSY,

PDS,

ZDS,

CRTISO, and

LCYE may determine the alteration of carotenoid content during fruit ripening [

97]. Our transcriptome data showed that only the expression levels of

HDS,

PSY,

ZDS, and

CRTISO were more abundant in roots than leaves and stems (

Figure 11b). However, trace expression of the

DWARF27 gene in leaves and low expression of the

CCD7 gene in roots, stems, and leaves suggested that they were two rate-limiting enzymes in azafrin biosynthesis.

DWARF27, which exhibits increased tillers and reduced plant height, was first studied in rice [

98]. It encodes an iron-containing protein localized in chloroplasts and is expressed mainly in vascular cells of shoots and roots [

98]. Further studies indicated that DWARF27 is an all-trans/9-cis isomerase which can convert all-trans-β-carotene into 9-cis-β-carotene in vivo and in vitro [

99]. Obviously, DWARF27 is vital for azafrin biosynthesis. What is interesting is that there is only one

CCD7 gene in our transcriptome which coincides with the all

CCD7 genes identified including maize, rice, sorghum,

Selaginella moellendorfii,

Physcomitrella patens, and

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and is a single copy [

100]. The highest expression of the

CCD7 gene was found in roots among maize,

A. thaliana, pea, and petunia [

100]. However, the highest expression in our transcriptome is in stems.

In the future, studies related to catalpol, acteoside, and azafrin biosynthesis will focus on the following aspects: (1) to construct a transgenic system for C. grandiflora Benth according to the successive tissue culture technology for verification of gene function, to characterize the putative genes of three pathways, and to verify their functions by enzyme assays in vitro or to overexpress them in vivo; (2) to explore the correlation between the contents of active component and related gene expression levels, to clone the putative TFs, and to verify their functions in the biosynthesis of active components via chromatin immunoprecipitation and overexpression in vivo; and (3) to figure out the biosynthetic pathway using feeding experiments with suspension cells.