1. Introduction

As a major site for nutrient metabolism and detoxification in the body, the liver plays a critical role in preventing exogenous toxic substances from entering the systemic blood stream [

1]. Factors such as bacterial and viral infection or inflammation lead to the activation of macrophages (Kupffer cells), which results in increased productions of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukine (IL)-1β and IL-6) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

2], and consequently parenchymal liver damage and dysfunction. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, is known to stimulate Kupffer cells (macrophages) and result in inflammatory liver injury [

3].

Lactobacillus casei (

L. casei) is regarded as a probiotic and is widely used in the food industry [

4]. This beneficial bacterium has attracted the focus of research due to its potential immunoregulatory effect. It has been demonstrated that specific

L. casei could modulate host immunity, which is positively correlated with the enhanced resistance to various viral and bacterial infections [

4]. The immunomodulatory effects are dependent on various factors, such as the intrinsic adjuvant properties, dose, viability, route and timing of administration of the specific

L. casei, as well as the physiological state and genetic background of the host [

5,

6,

7]. However, literature concerning the effects of

L. casei on liver inflammation and injury is scarce. Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine whether

L. casei could attenuate liver injury by using a piglet model with LPS challenge [

6].

3. Discussion

In this study, to investigate whether dietary supplementation of

L. casei could alleviate liver injury, we utilized a well-established porcine model with LPS-induced hepatic damage. In this animal model, liver injury was induced by intraperitoneal administration of

E. coli LPS. LPS, which commonly exists in the outer membrane of all Gram-negative bacteria, can bind to and activate the Kupffer cells (specialized macrophages located in the liver), resulting in the enhanced release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [

4,

5]. This LPS-induced liver injury model has been commonly used to elucidate the mechanism of inflammatory liver injury and the protective effects of nutritional ingredients, such as probiotics and amino acids [

6,

8,

9,

10].

The dose of

L. casei used for the present study was based on the results of our previous work regarding the effects of its dietary supplementation on LPS-induced liver injury on improving the growth performance of piglets [

11]. Interestingly, piglets fed the

L. casei diet exhibited a lower feed/gain ratio and a lower rate of diarrhea in comparison with those fed the basal diet. Diarrhea commonly occurs in early-weaned piglets because of their intestinal dysfunction in response to various challenges, such as social, environmental and dietary stresses [

6]. In

L. casei-supplemented piglets, reduced diarrhea incidence indicates an improvement in intestinal health. As a probiotic,

L. casei has been reported to enhance intestinal-mucosal barrier function and immunity [

12] and modulate the intestinal ecology [

11,

12,

13].

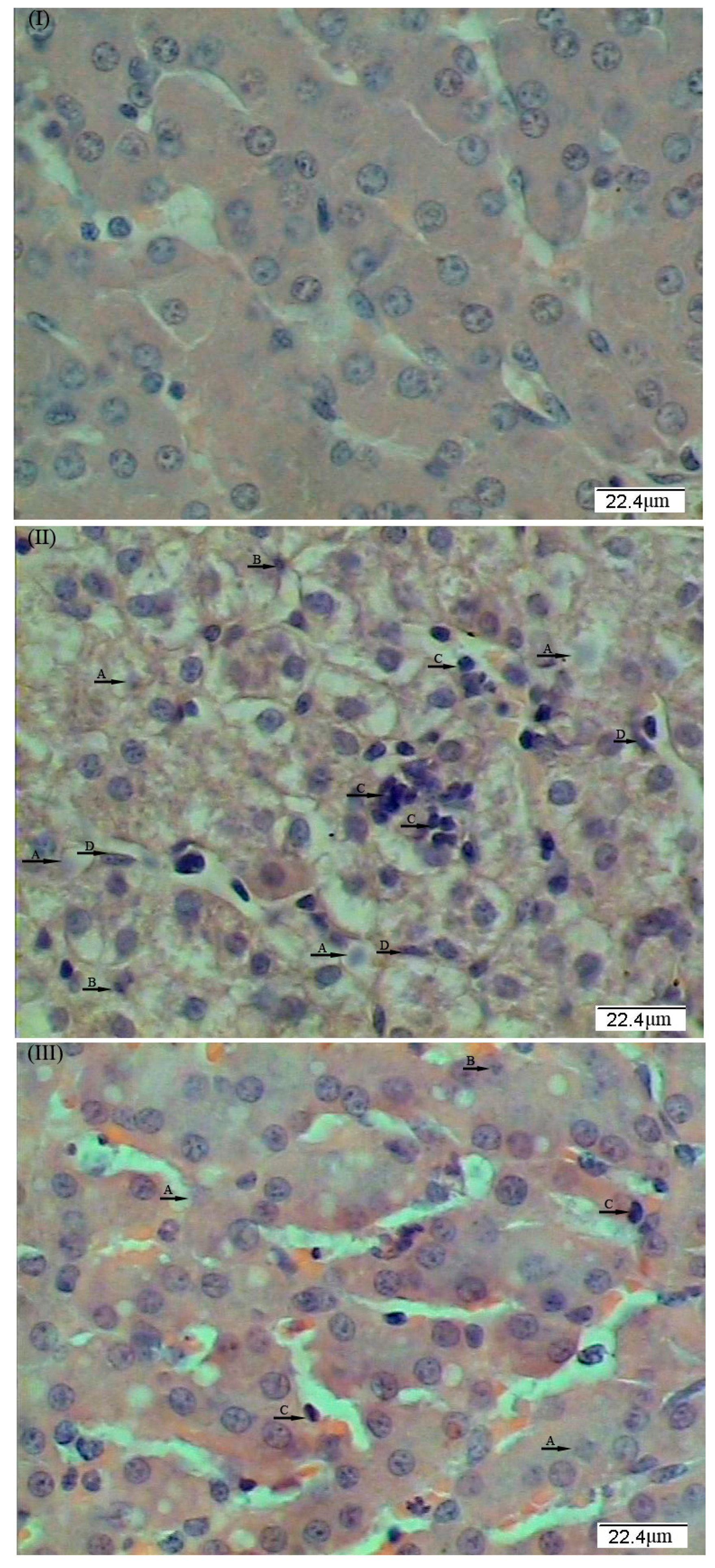

Plasma ALT, AST, and GGT activities are sensitive markers for hepatic damage [

2]. Results of the present study showed that dietary supplementation with

L. casei attenuated LPS-induced increases in plasma GGT activities, indicating a positive beneficial effect of

L. casei in ameliorating liver injury. These results are consistent with the histopathological changes in liver morphology, which demonstrated that dietary

L. casei supplementation mitigated the LPS-induced damage to the hepatic architecture. However, results on plasma ALT and AST activities indicated an incomplete recovery of the liver from LPS challenge, which may be due to the dosage of

L. casei (1 × 10

8 cfu/day per kg body weight) used in the present study. Of note, a higher dosage of

L. casei (6.8 × 10

10 cfu/day per kg body weight) could restore the plasma ALT activity to the normal level and protect the liver from fructose-induced steatosis in mice [

14]. Further studies are warranted to determine dose-dependent effects of

L. casei on hepatic structure and function.

LPS stimulated the release of inflammatory cytokines, which consequently induced the production of ROS and related peroxides, and ultimately resulted in the aggravation of the liver injury [

10]. However, the liver possesses defensive mechanisms against ROS through the actions of radical scavengers, such as SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px [

15]. In the present study, the activity of SOD in the liver was much lower in the LPS group than in the control group. Of note, dietary supplementation with

L. casei effectively mitigated the oxidative damage caused by LPS. Lactobacillus bacteria act through various mechanisms to defend animals against ROS toxicity, such as synthesizing SODs, producing hydroperoxidases, and accumulating high intracellular levels of metal ions. SOD defends against oxidative stress by scavenging O

2− into O

2 and H

2O

2, whereas catalase decomposes H

2O

2 into H

2O and O

2. It is likely that dietary supplementation with

L. casei improved the liver health in piglets through increasing the activity of SOD to protect against oxidative damage. Similarly, Wang et al. [

13] found that pretreatment with

L. casei significantly increased SOD activity in the homogenates of the liver challenged with LPS. Taken together, these findings support the notion that

L. casei is an effective agent for enhancing the anti-oxidative capacity in animals.

LPS also induces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by hepatic Kupffer cells via activating pattern recognition through toll-like receptors (TLRs) [

10]. Among the identified TLRs, TLR4 is a well defined receptor for LPS recognition. Upon activation, the TLR4 signaling drives Kupffer cells to produce a variety of inflammation-related cytokines [

16]. The nuclear regulatory factor κB (NF-κB) is a central regulator of cellular stress in all cell types in the liver. NF-κB activation is triggered via canonical pathways in response to a wide variety of stimuli, including pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as the bacterial and viral antigens that act on TLRs [

17]. Moreover, NF-κB is a family of dimeric transcription factors that regulate inflammation, innate and adaptive immunity, and wound healing responses, as well as cell fate and function [

18]. NF-κB plays these physiological roles by binding to κB sequences found in the regulatory regions of more than 200 target genes. The elevated abundance of NF-κB in the liver plays a mediatory role in the stimulatory effect of LPS on the production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) in piglets. To support this notion, we observed an increase in the concentrations of hepatic IL-6 and TNF-α in LPS-challenged piglets (

Table 3). In addition, NF-κB regulates the expression of many downstream genes that control cell proliferation, survival, stress responses, and immunity. Under LPS challenge,

TLR4 and

NF-κB mRNA levels were markedly enhanced, suggesting that TLR4 and NF-κB signaling pathways may be activated by LPS. However, the diet supplemented with

L. casei reduced the hepatic concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α, as well as the hepatic mRNA levels for pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g.,

IL-6 and

IL-8) in LPS-challenged piglets (

Table 5). Collectively, these results indicate that dietary supplementation with

L. casei attenuated the hepatic inflammation possibly via activating the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway.

In response to stresses, the mRNA abundance of hepatic heat shock protein HSP70 is usually enhanced to promote the refolding of partially-denatured proteins and prevent their aggregation, thereby protecting cells from injury [

8]. This is an adaptive mechanism for allowing organisms to survive heat shock stress. Therefore, a high level of

HSP70 is a sensitive indicator of oxidative stress in tissues [

19]. In the present study, the expression of the hepatic

HSP70 gene was dramatically increased in the liver of LPS-challenged piglets, but was decreased when the diet was supplemented with

L. casei. These results further support the notion that

L. casei plays an important role in ameliorating liver oxidative stress.

In summary, dietary supplementation with 6 × 10

6 cfu/g

L. casei exerts beneficial effects in alleviating liver injury in lipopolysaccharide-challenged piglets. The hepato-protective effects of

L. casei is closely associated with its role in increasing anti-oxidative capacity and reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines in the liver of piglets. These novel findings have important implications for improving the nutritional status of infected animals. As the piglet is a well-established animal model for studying human nutrition and disease [

6], findings from the porcine model may be used for the treatment of human liver disease.