Leachability and Chemical Profiles of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Electronic Waste Components: Targeted and Non-Targeted Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

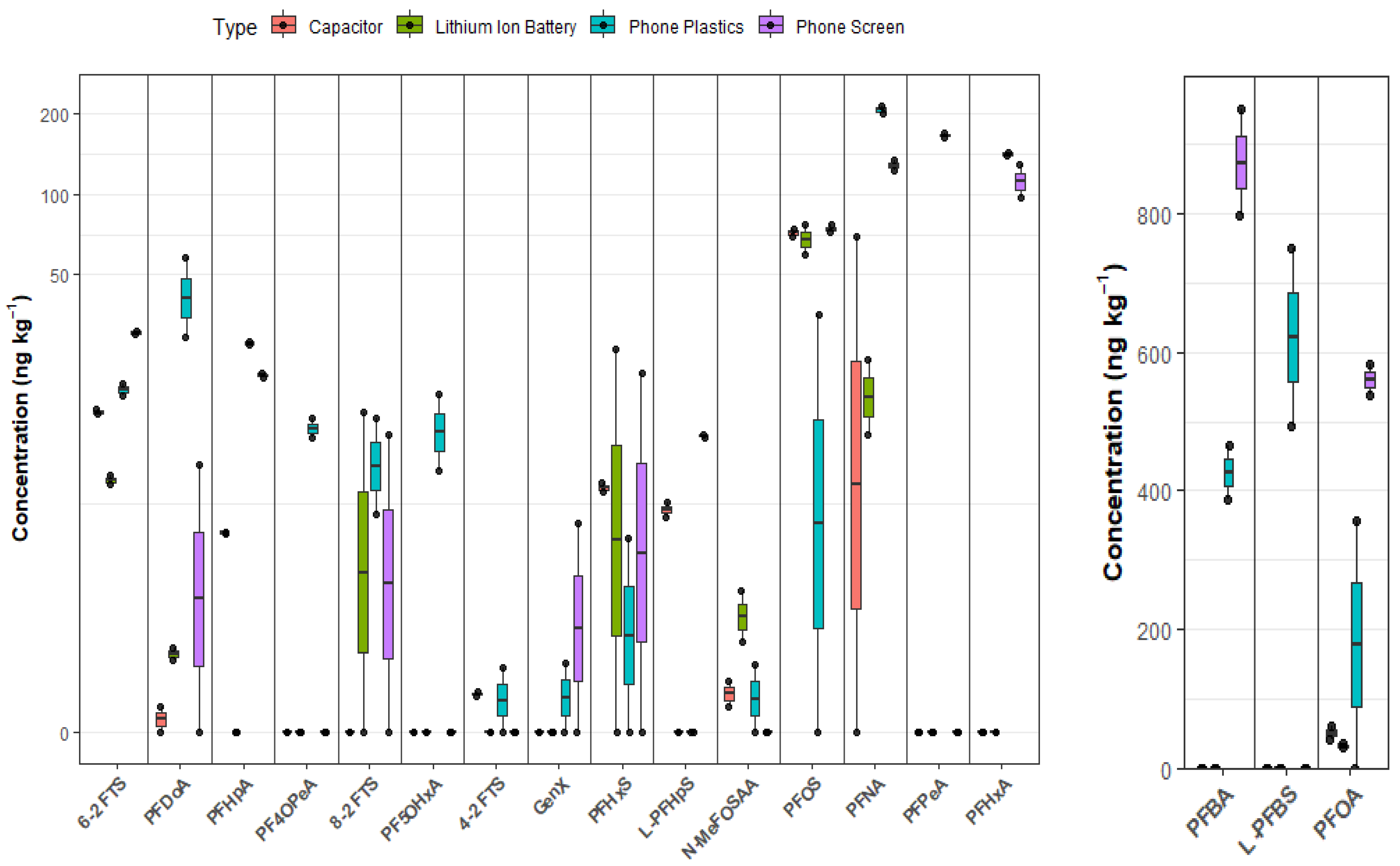

2.1. PFAS Content in E-Waste Components

2.2. Phone Screen and Phone Plastics

2.3. Capacitors and Lithium-Ion Batteries

2.4. Environmental Burden and Exposure Risks

2.4.1. Concentration vs. Mass Load

2.4.2. Exposure Routes

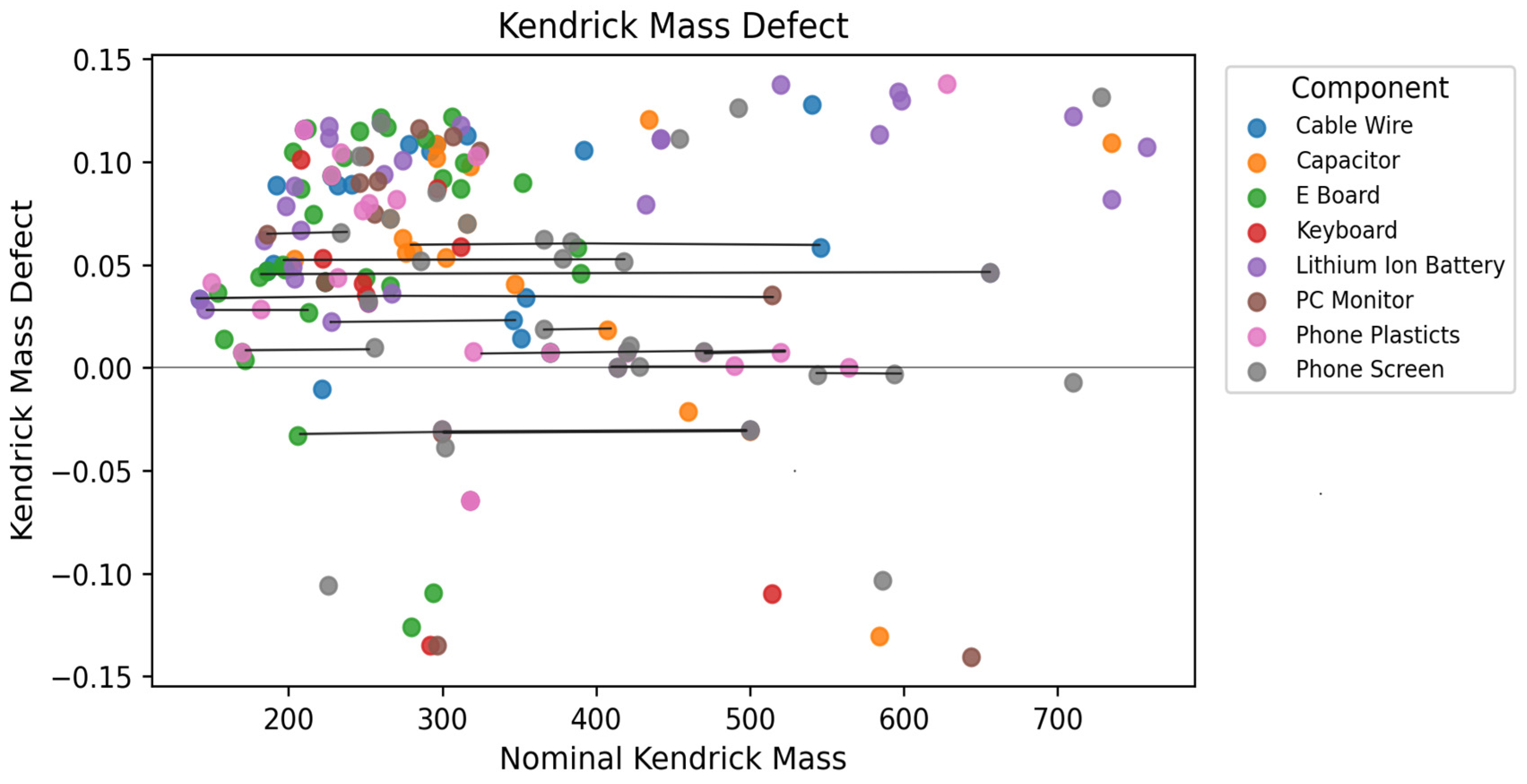

2.5. Screening of PFAS in E-Waste Samples Using Compound Discoverer v. 3.3

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. E-Waste Sampling and Sample Processing

3.3. Leaching Experiments

3.4. PFAS Sample Extraction and Analysis

3.5. Data Processing for Targeted Analysis

3.6. PFAS Screening for Non-Targeted Analysis Identification

3.7. NTA Data Processing: Compound DiscoverTM (CD) v. 3.3

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, K.; Tan, Q.; Yu, J.; Wang, M. A global perspective on e-waste recycling. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Kumar, D.; Chaudhary, J.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, S.; Singh Verma, A. Review on E-waste management and its impact on the environment and society. Waste Manag. Bull. 2023, 1, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinete, N.; Tansel, B.; Katsenovich, Y.; Ocheje, J.O.; Mendoza Manzano, M.; Nasir, Z. Leaching profile of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from selected e-waste components and potential exposure pathways from discarded components. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 491, 137953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, B. PFAS use in electronic products and exposure risks during handling and processing of e-waste: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, L.G.T. Historical and current usage of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A literature review. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2023, 66, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankit; Saha, L.; Kumar, V.; Tiwari, J.; Sweta; Rawat, S.; Singh, J.; Bauddh, K. Electronic waste and their leachates impact on human health and environment: Global ecological threat and management. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 24, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.; Cobo, M.; Rodríguez, I. Identification of hazardous organic compounds in e-waste plastic using non-target and suspect screening approaches. Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITRC. PFAS Releases to the Environment; ITRC: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Benskin, J.P.; Li, B.; Ikonomou, M.G.; Grace, J.R.; Li, L.Y. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in landfill leachate: Patterns, time trends, and sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11532–11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.N.; Sikarwar, V.S.; Bisen, D.; Fathi, J.; Maslani, A.; Lopez Nino, B.N.; Barmavatu, P.; Kaviti, A.K.; Pohořelý, M.; Buryi, M. E-Waste Unplugged: Reviewing Impacts, Valorization Strategies and Regulatory Frontiers for Efficient E-Waste Management. Processes 2025, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. Interim Guidance on the Destruction and Disposal of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Materials Containing Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances—Version 2 (2024); U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhi, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Yue, D.; Wang, X. Leaching of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from food contact materials with implications for waste disposal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolaymat, T.; Robey, N.; Krause, M.; Larson, J.; Weitz, K.; Parvathikar, S.; Phelps, L.; Linak, W.; Burden, S.; Speth, T.; et al. A critical review of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) landfill disposal in the United States. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Zhang, J.; Thiessen, P.A.; Chirsir, P.; Kondic, T.; Bolton, E.E. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in PubChem: 7 Million and Growing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 16918–16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugsel, B.; Zweigle, J.; Zwiener, C. Nontarget screening strategies for PFAS prioritization and identification by high resolution mass spectrometry: A review. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 40, e00216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqar, M.; Zhao, M.; Saleem, R.; Cheng, Z.; Fang, B.; Dong, X.; Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Sun, H. Identification of Emerging Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in E-waste Recycling Practices and New Precursors for Trifluoroacetic Acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 16153–16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Baqar, M.; Yu, H.; Qiao, B.; Sun, H. Electronic-waste-associated pollution of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: Environmental occurrence and human exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 451, 131204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Martín, D.; Castro, G.; González, S.V.; Arp, H.P.H.; López-Serna, R.; Asimakopoulos, A.G. A comprehensive analytical approach to monitoring selected emerging contaminant classes in sewage sludge and e-waste from Norway. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol. 2025, 7, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiers, E.; Scholl, J.; Droas, M.; Vogel, C.; Leube, P.; Sommerfeld, T.; Bagheri, A.; Adam, C.; Seubert, A.; Koch, M. Development and evaluation of analytical strategies for the monitoring of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from lithium-ion battery recycling materials. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2025, 417, 6567–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Han, J.; Lichtfouse, E. Fluoropolymers and nanomaterials, the invisible hazards of cell phone and computer touchscreens. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Alternatives in Coatings, Paints and Varnishes (CPVs); OECD: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation Rulemaking; U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Meng, L.; Song, B.; Lu, Y.; Lv, K.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, G. The occurrence of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in fluoropolymer raw materials and products made in China. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 107, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glüge; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2020, 22, 2345–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, S.Y.; Aris, A.Z. Revisiting the “forever chemicals”, PFOA and PFOS exposure in drinking water. npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, D.; Keyte, I.; Tiscione, S.; Kreissig, J. Check Your Tech; A guide to PFAS in electronics; WSP: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, F.; Jing, Z.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; Dong, H.; Tan, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Owen, R.; Shearing, P.R.; et al. Trace amounts of fluorinated surfactant additives enable high performance zinc-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 53, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. EPA. Technical Fact Sheet—Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA); U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Guelfo, J.L.; Ferguson, P.L.; Beck, J.; Chernick, M.; Doria-Manzur, A.; Faught, P.W.; Flug, T.; Gray, E.P.; Jayasundara, N.; Knappe, D.R.U.; et al. Lithium-ion battery components are at the nexus of sustainable energy and environmental release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rensmo, A.; Savvidou, E.K.; Cousins, I.T.; Hu, X.; Schellenberger, S.; Benskin, J.P. Lithium-ion battery recycling: A source of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to the environment? Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2023, 25, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global E-Waste Monitor. Electronic Waste Rising Five Times Faster Than Documented E-Waste Recycling: UN. 2024. Available online: https://ewastemonitor.info/the-global-e-waste-monitor-2024/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Trade-Off Analysis Methodology to Evaluate Alternatives for Water Resource Management (Technical Memorandum M&S-2021-G1364); Technical Service Center, Economic Analysis Group: Denver, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. Framework for Human Health Risk Assessment to Inform Decision Making (EPA/100/R-14/001); Risk Assessment Forum, Office of the Science Advisor: Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- FAO. Guidelines for Risk Analysis of Foodborne Antimicrobial Resistance; Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC): Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad, B.M.; Irizarry, R.A.; Åstrand, M.; Speed, T.P. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonnet, J.A.; McDonough, C.A.; Xiao, F.; Schwichtenberg, T.; Cao, D.; Kaserzon, S.; Thomas, K.V.; Dewapriya, P.; Place, B.J.; Schymanski, E.L.; et al. Communicating Confidence of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Identification via High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2022, 9, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atomfair. Atomfair 1H-Perfluorohexane C6HF13 CAS 355-37-3. 2025. Available online: https://atomfair.com/product/atomfair-1h-perfluorohexane-c6hf13-cas-355-37-3/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Qorvo. Mfg Banned & Restricted Substance List 2025; Qorvo: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.F.; Yuan, Y.; Wei, Y.-C.; Chan, W.-H.; Fu, L.-W.; Su, B.-K.; Chen, I.-Y.; Chou, K.-J.; Chen, P.-T.; Hsu, H.-F.; et al. Highly Efficient Near-Infrared Electroluminescence up to 800 nm Using Platinum(II) Phosphors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2002173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.A.; Aungst, J.; Cooper, J.; Bandele, O.; Kabadi, S.V. Comparative analysis of the toxicological databases for 6:2 fluorotelomer alcohol (6:2 FTOH) and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 138, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, P.; Barzen-Hanson, K.A.; Helbling, D.E. Target and Nontarget Analysis of Per- and Polyfluoralkyl Substances in Wastewater from Electronics Fabrication Facilities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 2346–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.; Quinete, N.; Gardinali, P. Differential Organic Contaminant Ionization Source Detection and Identification in Environmental Waters by Nontargeted Analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 41, 1154–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zweigle, J.; Bugsel, B.; Zwiener, C. Efficient PFAS prioritization in non-target HRMS data: Systematic evaluation of the novel MD/C-m/C approach. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 1791–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Liang, Y.; Wang, K.; Liao, J.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, X.; Peng, X.; Mai, B.; Huang, Q.; Lin, H. Comprehensive characterization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in wastewater by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry and screening algorithms. npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugsel, B.; Zwiener, C. LC-MS screening of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in contaminated soil by Kendrick mass analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 4797–4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strynar, M.; McCord, J.; Newton, S.; Washington, J.; Barzen-Hanson, K.; Trier, X.; Liu, Y.; Dimzon, I.K.; Bugsel, B.; Zwiener, C.; et al. Practical application guide for the discovery of novel PFAS in environmental samples using high resolution mass spectrometry. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 33, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, J.L.; Slee, D.; Falvey, S.; Kookana, R.; Bekele, E.; Stevenson, G.; Lee, A.; Davis, G.B. Laboratory batch representation of PFAS leaching from aged field soils: Intercomparison across new and standard approaches. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fatowe, M.; Cui, D.; Quinete, N. Assessment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in Biscayne Bay surface waters and tap waters from South Florida. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 806, 150393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ocheje, J.O.; Manzano, M.M.; Nasir, Z.; Katsenovich, Y.; Tansel, B.; Sivaprasad, S.; Quinete, N. Analytical protocol for detection and prioritization of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in biosolid leachates. J. Water Process. Eng. 2024, 68, 106546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PFAS | DF (%) | Phone Screen (ng·kg−1) | Lithium-Ion Battery (ng·kg−1) | Capacitor (ng·kg−1) | Phone Plastics (ng·kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFBA | 50.0 | 873 ± 108 | <0.0900 | <0.0900 | 426 ± 54.4 |

| PF4OPeA | 25.0 | <0.0400 | <0.0400 | <0.0400 | 13.4 ± 1.58 |

| PFPeA | 25.0 | <0.0400 | <0.0400 | <0.0400 | 165 ± 4.60 |

| L-PFBS | 25.0 | <0.0200 | <0.0200 | <0.0200 | 621 ± 182 |

| PFHxA | 50.0 | 112 ± 22.3 | <0.0200 | <0.0200 | 140 ± 3.44 |

| GenX | 25.0 | 2.88 ± 4.08 | <0.0400 | <0.0400 | 0.634 ± 0.896 |

| PFHxS | 63.0 | 10.7 ± 15.2 | 13.3 ± 18.8 | 8.00 ± 0.472 | 2.53 ± 3.58 |

| PFHpA | 75.0 | 21.2 ± 0.480 | <0.0200 | 5.32 ± 0.0800 | 27.8 ± 0.615 |

| 6-2 FTS | 100 | 30.4 ± 0.759 | 8.53 ± 0.476 | 15.5 ± 0.520 | 18.7 ± 1.29 |

| PFHpS | 50.0 | 12.5 ± 0.139 | <0.0600 | 6.57 ± 0.585 | <0.0600 |

| PFOA | 88.0 | 560 ± 31.7 | 33.3 ± 4.29 | 51.6 ± 12.4 | 178 ± 252 |

| PFOS | 88.0 | 74.2 ± 3.23 | 68.0 ± 12.3 | 71.7 ± 3.60 | 17.7 ± 25.1 |

| PFNA | 88.0 | 128 ± 7.76 | 18.4 ± 8.23 | 34.7 ± 49.0 | 206 ± 9.20 |

| 8-2 FTS | 50.0 | 6.30 ± 8.91 | 7.70 ± 10.9 | <0.0200 | 10.5 ± 5.96 |

| N-MeFOSAA | 63.0 | <0.0600 | 2.37 ± 0.938 | 0.676 ± 0.324 | 0.614 ± 0.868 |

| PFDoA | 75.0 | 4.88 ± 6.89 | 1.44 ± 0.190 | 0.228 ± 0.322 | 43.5 ± 20.2 |

| ∑PFAS | - | 1739–1932 | 148–158 | 147–243 | 1575–2197 |

| Component | Compound | Conc. (ng·kg−1) | Hazard | Exposure | Release Potential Modifier | Hazard Score | Exposure Score | Adjusted Exposure Score | Concentration Score | Risk Score (Quantitative) | Overall Risk Score (Qualitative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phone Screen | PFOA | 560 | High | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.850 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.13 | 3 | 2.65 | Medium-High |

| PFBA | 873 | Medium | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.850 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.13 | 3 | 2.25 | Medium-High | |

| PFOS | 74.0 | High | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.850 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.13 | 3 | 2.65 | Medium-High | |

| Phone Plastic | PFBS | 621 | Medium-High | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.950 | 2.50 | 2.50 | 2.38 | 3 | 2.55 | Medium-High |

| PFNA | 206 | High | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.950 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.38 | 3 | 2.75 | High | |

| 6:2 FTS | 18.7 | Medium | Low (Direct Use), High (E-Waste) | 0.950 | 2.00 | 2.50 | 2.38 | 1 | 1.95 | Medium | |

| Capacitor | PFOS | 71.7 | High | High | 1.15 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.45 | 2 | 2.98 | High |

| PFOA | 51.6 | High | High | 1.15 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.45 | 2 | 2.98 | High | |

| PFNA | 34.7 | High | Medium-High | 1.15 | 3.00 | 2.50 | 2.88 | 2 | 2.75 | High | |

| 6:2 FTS | 15.5 | Medium | Medium | 1.15 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.30 | 1 | 1.92 | Medium | |

| PFHxS/PFHpS | 8.00 | High | Low | 1.15 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1 | 1.86 | Medium | |

| Lithium-ion Battery | PFOS | 68.0 | High | High | 1.20 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 3.60 | 2 | 3.04 | High |

| PFOA | 33.0 | High | Medium | 1.20 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.40 | 2 | 2.56 | Medium-High | |

| PFNA | 18.0 | High | Low-Medium | 1.20 | 3.00 | 1.50 | 1.80 | 1 | 2.12 | Medium | |

| PFHxS | 13.0 | High | Low | 1.20 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1 | 1.88 | Medium | |

| 6:2 FTS | 8.50 | Medium | Low | 1.20 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.20 | 1 | 1.48 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ocheje, J.O.; Katsenovich, Y.; Tansel, B.; Dufresne, C.P.; Quinete, N. Leachability and Chemical Profiles of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Electronic Waste Components: Targeted and Non-Targeted Analysis. Molecules 2026, 31, 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030445

Ocheje JO, Katsenovich Y, Tansel B, Dufresne CP, Quinete N. Leachability and Chemical Profiles of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Electronic Waste Components: Targeted and Non-Targeted Analysis. Molecules. 2026; 31(3):445. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030445

Chicago/Turabian StyleOcheje, Joshua O., Yelena Katsenovich, Berrin Tansel, Craig P. Dufresne, and Natalia Quinete. 2026. "Leachability and Chemical Profiles of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Electronic Waste Components: Targeted and Non-Targeted Analysis" Molecules 31, no. 3: 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030445

APA StyleOcheje, J. O., Katsenovich, Y., Tansel, B., Dufresne, C. P., & Quinete, N. (2026). Leachability and Chemical Profiles of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Electronic Waste Components: Targeted and Non-Targeted Analysis. Molecules, 31(3), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31030445