Design of a Recyclable Photoresponsive Adsorbent via Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles in Porous Aromatic Frameworks for Low-Energy Desulfurization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

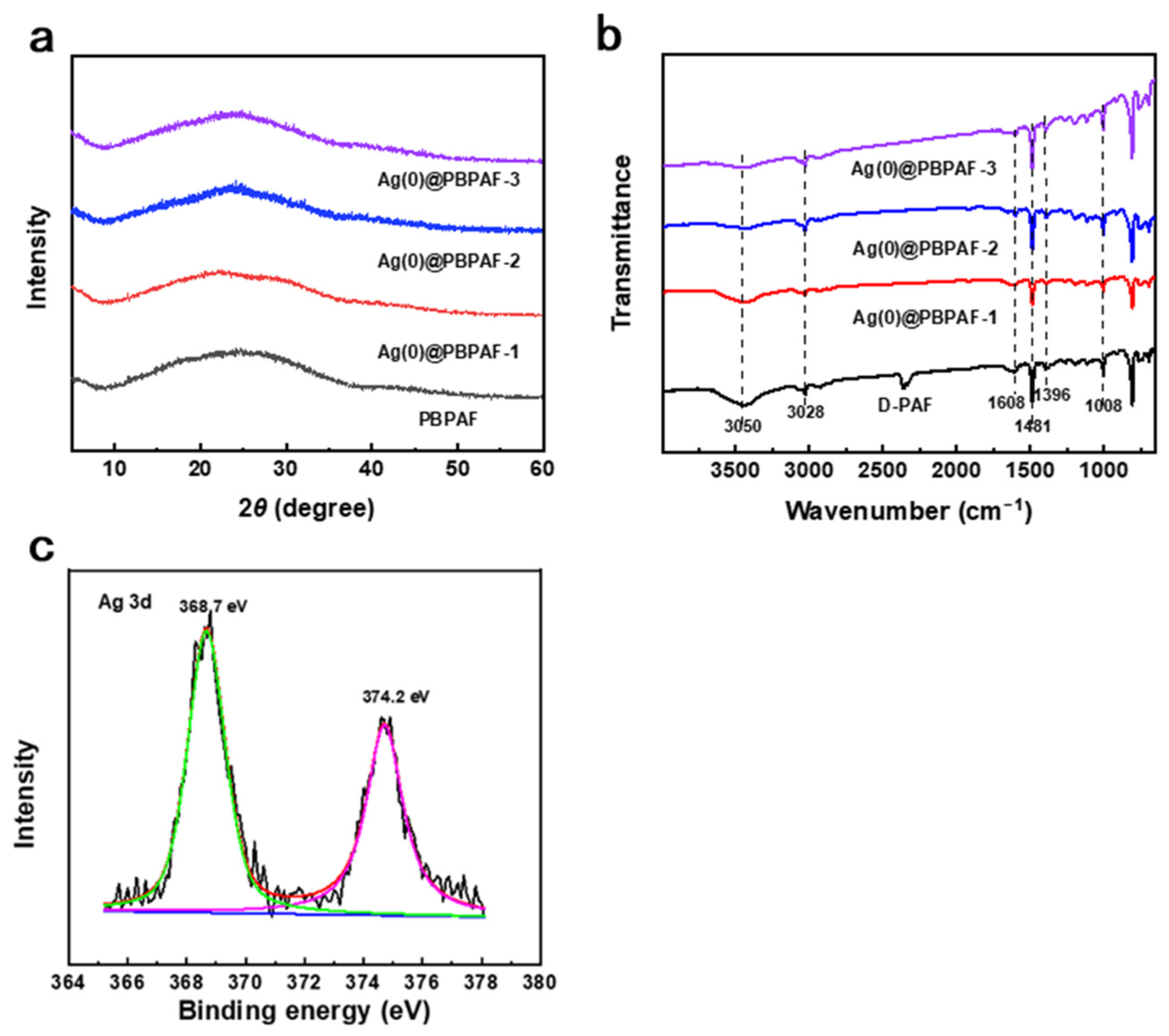

2.1. Structure and Surface Properties of Ag(0)@PBPAF Composites

2.2. Photothermal Performance of Ag(0)@PBPAF Composites

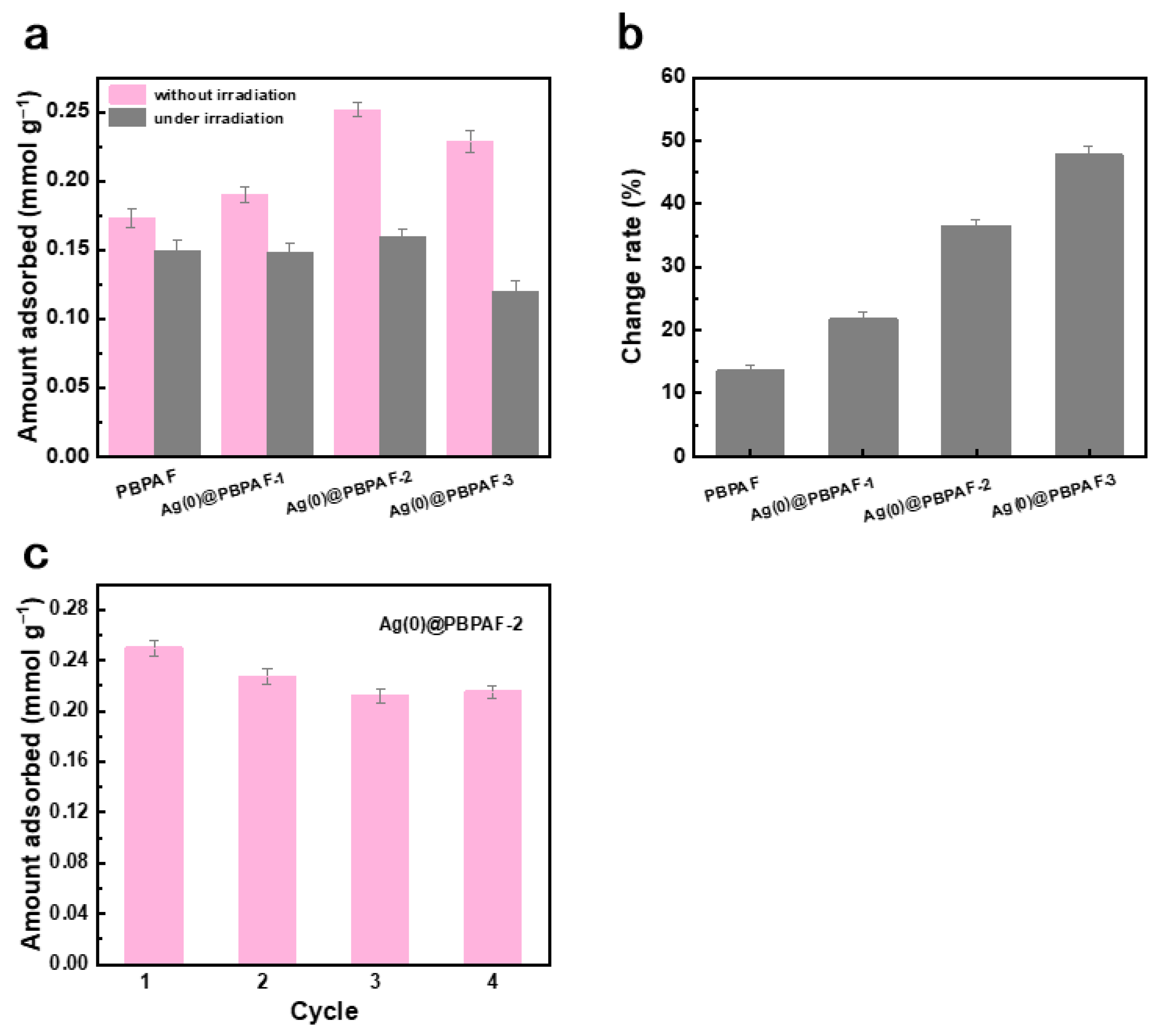

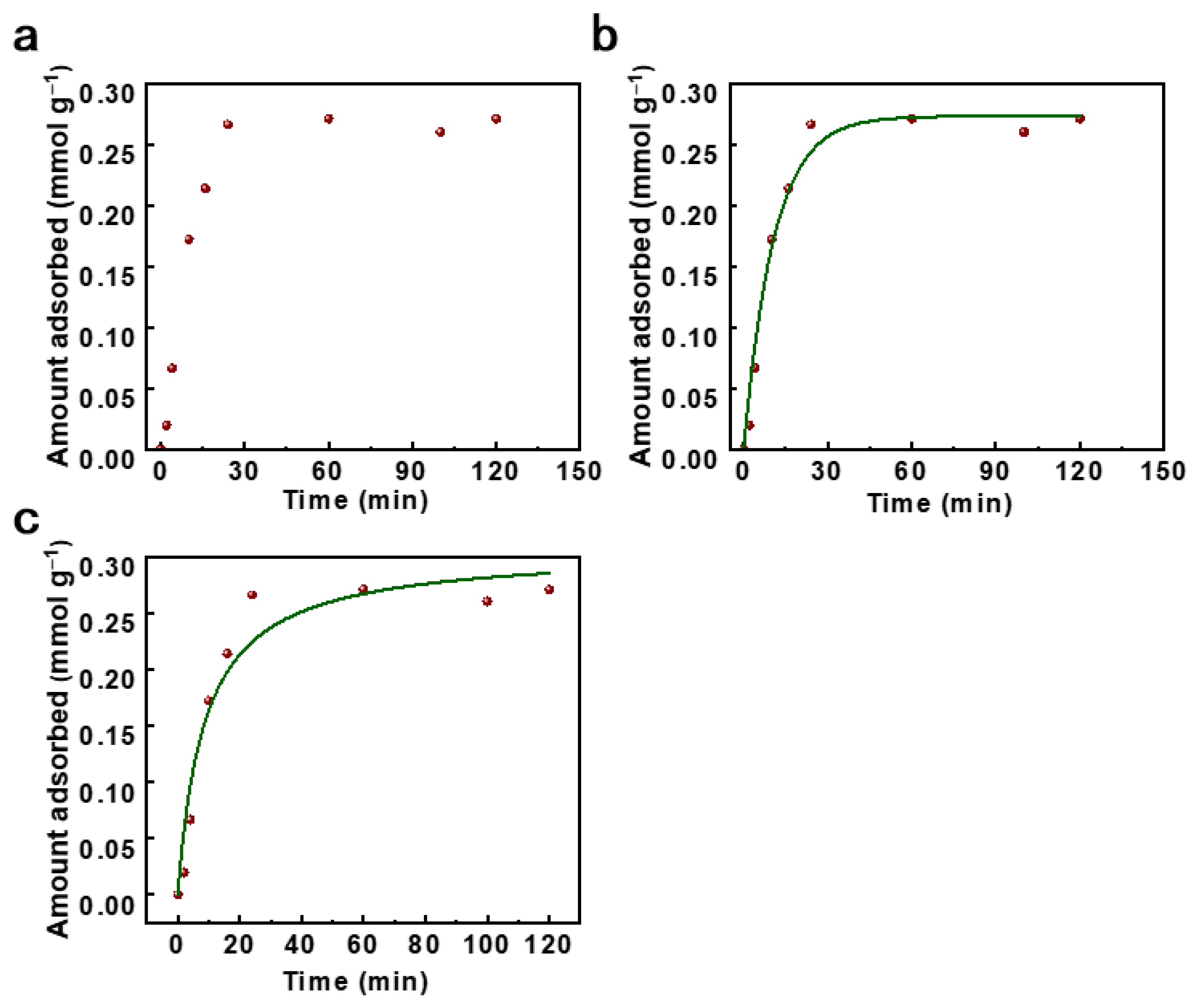

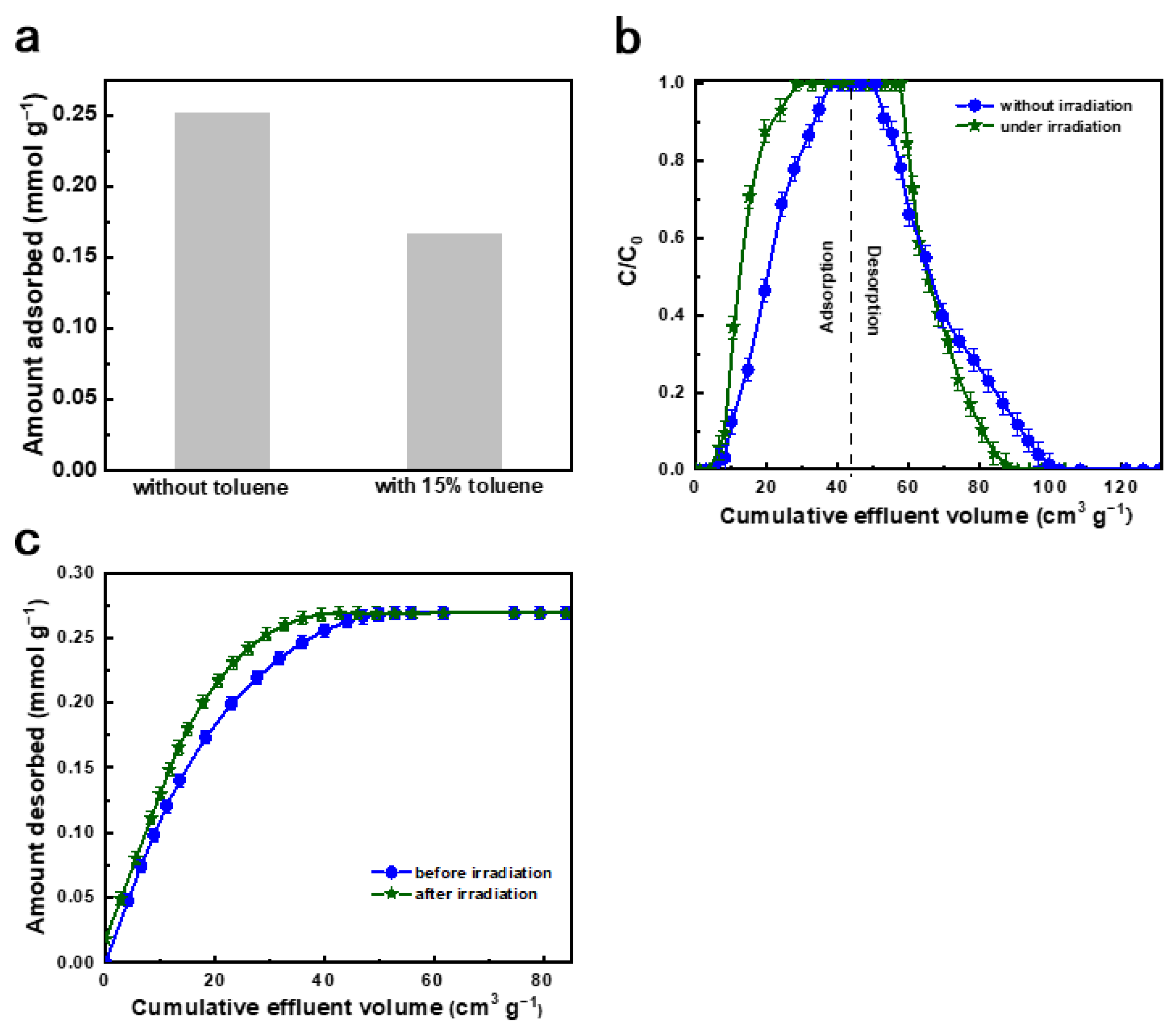

2.3. Adsorptive Desulfurization Performance of Ag(0)@PBPAF

2.4. Discussion on Adsorption Mechanism and Future Perspectives

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of Materials

3.2. Materials Characterization

3.3. Adsorption Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, H.; Ko, K.J.; Mofarahi, M.; Kim, K.M.; Lee, C.H. Adsorption behavior and mechanism of ultra-low concentration sulfur compounds in natural gas on Cuimpregnated activated carbon. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 470, 144274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Li, J.Y.; Chen, C.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, W.S.; Li, H.M.; Di, J. Universal strategy engineering grain boundaries for catalytic oxidative desulfurization. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 317, 121714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.Q.; Wang, J.W. Effects of B2O3 on the adsorption desulfurization performance of Ag-CeOx/TiO2-SiO2 adsorbent as well as its adsorption-diffusion study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.C.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Dong, G. Effect of ligands of functional magnetic MOF-199 composite on thiophene removal from model oil. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 2979–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.C.; Lin, Y.; Wu, S.H.; Zhong, Y.Y.; Yang, C.P. Molybdenum dioxide nanoparticles anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as oxidative desulfurization catalysts: Role of electron transfer in activity and reusability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2100442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thepwatee, S.; Song, C.S. Light-enhanced oxidative adsorption desulfurization of diesel fuel over TiO2-ZrO2 Mixed Oxides. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 17512–17521. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, M.Q.; Hu, H.; Ye, Z.L.; Huang, Q.M.; Chen, X.H. Adsorption desulfurization performance and adsorption-diffusion study of B2O3 modified Ag-CeOx/TiO2-SiO2. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 362, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Xu, H.; Kong, W.J.; Shang, M.; Dai, H.X.; Yu, J.Q. Overcoming the limitations of directed C-H functionalizations of heterocycles. Nature 2014, 515, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Du, J.H.; Xiao, Y.H.; Zhao, Q.D.; He, G.H. Hierarchical porous HKUST-1 fabricated by microwave-assisted synthesis with CTAB for enhanced adsorptive removal of benzothiophene from fuel. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 271, 118868–118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, S.A.; Alhooshani, K.; Sulaiman, K.O.; Qamaruddin, M.; Bakare, I.A.; Tanimu, A.; Saleh, T.A. Influence of aluminium impregnation on activated carbon for enhanced desulfurization of DBT at ambient temperature: Role of surface acidity and textural properties. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 303, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.Q.; Zhang, L.; Tang, T.D.; Ke, Q.P.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.B.; Fang, G.Y.; Li, J.X.; Xiao, F.S. Extraordinarily high activity in the hydrodesulfurization of 4,6-dimethyl dibenzothiophene over Pd supported on mesoporous zeolite Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 15346–15349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cychosz, K.A.; Wong-Foy, A.G.; Matzger, A.J. Enabling cleaner fuels: Desulfurization by adsorption to microporous coordination polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14538–14543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, N.; Rangarajan, S.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, J.; Mavrikakis, M.; Lauritsen, J.V. Site-dependent reactivity of MoS2 nanoparticles in hydrodesulfurization of thiophene. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushkevich, V.L.; Popov, A.G.; Ivanova, I.I. Sulfur-33 isotope tracing of the hydrodesulfurization process: Insights into the reaction mechanism, catalyst characterization and improvement. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 10872–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, X.W.; Tao, Z.P.; Li, B.Z.; Zhao, D.F.; Gao, H.Y.; Zhu, Z.P.; Wang, G.; Shu, X.T. Defect engineering and post-synthetic reduction of Cu based metalorganic frameworks towards efficient adsorption desulfurization. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Yin, M.L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.L.; Ye, C.S.; Qiu, T. IF-8-derived P, N-Co-doped hierarchical carbon: Synergistic and high-efficiency desulfurization adsorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 429, 132458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.H.; Fu, J.H.; Zhu, H.Y.; Zhao, Q.D.; Zhou, L. Facile and controllable preparation of nanocrystalline ZSM-5 and Ag/ZSM-5 zeolite with enhanced performance of adsorptive desulfurization from fuel. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Voorde, B.; Boulhout, M.; Vermoortele, F.; Horcajada, P.; Cunha, D.; Lee, J.S.; Chang, J.S.; Gibson, E.; Daturi, M.; Lavalley, J.C.; et al. N/S-Heterocyclic contaminant removal from fuels by the mesoporous metalorganic framework MIL-100: The role of the metal ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9849–9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.L.; Liu, Q.F.; Xing, J.M.; Gao, H.S.; Xiong, X.C.; Li, Y.G.; Li, X.; Liu, H.Z. Highefficiency desulfurization by adsorption with mesoporous aluminosilicates. AIChE J. 2007, 53, 3263–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Lai, D.; Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.X.; Wu, K.Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Yang, Q.W.; Yang, Y.W.; Chen, B.L.; et al. Deep desulfurization with record SO2 adsorption on the metal-organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9040–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, L.B.; Liu, X.Q.; AlBahily, K.; Ravonb, U.; Vinu, A. Design and fabrication of nanoporous adsorbents for the removal of aromatic sulfur compounds. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 23978–24012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Shen, J.X.; Peng, S.S.; Zhang, J.K.; Wu, J.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Enhancing oxidation resistance of Cu(I) by tailoring microenvironment in zeolites for efficient adsorptive desulfurization. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, J.; Ling, H.; Ju, F. Reactive adsorption desulfurization of FCC gasoline over self-sulfidation adsorbent. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 318, 123989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.P.; Xie, W.; Li, H.; Li, J.P.; Hu, J.; Liu, H.L. Construction of hydrophobic channels on Cu(I)-MOF surface to improve selective adsorption desulfurization performance in presence of water. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 285, 120287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Jin, M.M.; Shi, S.; Qi, S.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Adjusting accommodation microenvironment for Cu+ to enhance oxidation inhibition for thiophene capture. AIChE J. 2021, 67, 17368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guragain, S.; Bastakoti, B.P.; Malgras, V.; Nakashima, K.; Yamauchi, Y. Multi-stimuli-responsive polymeric materials. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 13164–13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.Q.; Qin, W.K.; Mei, T.; Chen, C.Q. Bi-material sinusoidal beam-based temperature responsive multistable metamaterials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2023, 277, 112343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.N.; Yao, Y.Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z.G.; Xue, Y.; Li, B.; Ma, Y.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Wu, H.L. Recent studies on proteins and polysaccharides-based pH-responsive fluorescent materials. Int. J. Bio Macromol. 2024, 260, 129534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabás, H.; Melinda, R.; Sándor, G.; István, S.; Réka, B. Magnetic field response of aqueous hydroxyapatite based magnetic suspensions. Heliyon 2019, 5, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.J.; Zheng, L.; Qi, S.C.; Li, J.X.; Xue, D.M.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Maintaining the configuration of a light-responsive metal-organic framework: LiYGeO4:Bi3+-incorporation-induced long-term bending through short-time light irradiation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2023, 11, 17484–17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.T.; Zheng, X.D.; Zhang, X.; Li, G.M.; Mei, J.F.; Li, Z.Y. Construction of smart photo-responsive imprinted composite aerogel and its selective adsorption for recovery of rare earth dysprosium ions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124618–124628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Ji, W.H.; Wang, J.Q.; Wang, N.X.; Wu, W.X.; Wu, Q.; Hou, X.Y.; Hu, W.B.; Li, L. Near infrared photothermal conversion materials: Mechanism, preparation, and photothermal cancer therapy applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 7909–7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoyi, H.K.; Urbas, A.; Li, Q. Soft materials driven by photothermal effect and their applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1800458–1800479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Z.J.; Liu, S.Y.; Wen, H.; Liu, G.l.; Yang, T.; Li, J.J.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Detachable Porous Organic Polymers Responsive to Light and Heat. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202301739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tan, P.; Qi, S.C.; Gu, C.; Peng, S.S.; Wu, F.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Breathing metal–organic polyhedra controlled by light for carbon dioxide capture and liberation. CCS Chem. 2021, 3, 1659–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Qi, S.C.; Gao, X.J.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Ce-doped smart adsorbents with photoresponsive molecular switches for selective adsorption and efficient desorption. Engineering 2020, 6, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Making porous materials respond to visible light. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2656–2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tan, P.; Qi, S.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Yan, J.H.; Fan, F.; Sun, L.B. Metal-organic frameworks with target-specific active sites switched by photoresponsive motifs: Efficient adsorbents for tailorable CO2 capture. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 6600–6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycenga, M.; Cobley, C.; Zeng, J.; Li, W.Y.; Moran, C.H.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, D.; Xia, Y.N. Controlling the synthesis and assembly of silver nanostructures for plasmonic applications. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 3669–3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Tan, P.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Photomodulation on adsorptive desulfurization by Ag(0): Photothermal active sites with high stability. AIChE J. 2023, 69, 18034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; An, S.H.; Yang, X.J.; Hu, J.; Wang, H.L.; Liu, H.L.; Tian, Z.Q.; Jiang, D.E.; Mehio, N.D.; Zhu, X. Efffcient adsorptive desulfurization by task-speciffc porous organic polymers. AIChE J. 2016, 62, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.M.; Kim, D.; Rungtaweevoranit, B.; Trickett, C.A.; Barmanbek, J.T.D.; Alshammari, A.S.; Yang, P.D.; Yaghi, O.M. Plasmon-enhanced photocatalytic CO2 conversion within metal organic frameworks under visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Luo, B.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Chen, S. Visible light photocatalytic activity enhancement and mechanism of AgBr/Ag3PO4 hybrids for degradation of methyl orange. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 217, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, X.M.; Yin, D.; Fan, Y.P.; Zhang, Q.; Du, P.Y.; Zhang, D.X.; Chen, J.; Lu, X.Q. Plasmon-enhanced charge separation and surface reactions based on Ag-loaded transition-metal hydroxide for photoelectrochemical water oxidation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.D.; Chen, B.; Wang, G.G.; Ma, S.; Cheng, L.; Liu, W.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Q.Q. Controlled growth of hierarchical Bi2Se3/CdSe-Au nanorods with optimized photothermal conversion and demonstrations in photothermal therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 4424–4524. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Xu, J.F.; Zhang, X. A bacteria-responsive porphyrin for adaptable photodynamic/photothermal therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, 799–816. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.K.; Tan, P.; Lu, J.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, L.B. Fabrication of photothermal silver nanocube/ZIF-8 composites for visible-light-regulated release of propylene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 29298–29304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, G.; Song, H.L.; Cui, X.H.; Li, F.; Yuan, D. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies on adsorption of thiophene and benzothiophene onto AgCeY Zeolite. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 693, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, R.; Husmann, M.; Weinlaender, C.; Kienzl, N.; Leitner, E.; Hochenauer, C. Acid base interaction and its influence on the adsorption kinetics and selectivity order of aromatic sulfur heterocycles adsorbing on Ag-Al2O3. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 309, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, N.B.; Santos, E. Ab Initio Studies of Ag−S Bond Formation during the Adsorption of L-Cysteine on Ag(111). Langmuir 2012, 28, 11472–11483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, B.O.; Jalilehvand, F.; Mah, V.; Parvez, M.; Wu, Q. Silver(I) Complex Formation with Cysteine, Penicillamine, and Glutathione. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 4593–4602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | SBET (m2·g−1) | Vp (cm3·g−1) | Ag (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBPAF | 616 | 0.63 | - |

| Ag(0)@PBPAF-1 | 444 | 0.32 | 3.85 |

| Ag(0)@PBPAF-2 | 400 | 0.31 | 7.88 |

| Ag(0)@PBPAF-3 | 327 | 0.30 | 10.21 |

| Sample | Pseudo-First-Order Model | Pseudo-Second-Order Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qe (mmol·g−1) | k1 (min−1) | R2 | Qe (mmol·g−1) | k2 (min−1) | R2 | |

| Ag(0)@PBPAF-2 | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.28 | 0.37 | 0.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Li, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, Q. Design of a Recyclable Photoresponsive Adsorbent via Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles in Porous Aromatic Frameworks for Low-Energy Desulfurization. Molecules 2026, 31, 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020248

Li T, Li X, Wu H, Chen Q. Design of a Recyclable Photoresponsive Adsorbent via Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles in Porous Aromatic Frameworks for Low-Energy Desulfurization. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):248. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020248

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Tiantian, Xiaowen Li, Hao Wu, and Qunyu Chen. 2026. "Design of a Recyclable Photoresponsive Adsorbent via Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles in Porous Aromatic Frameworks for Low-Energy Desulfurization" Molecules 31, no. 2: 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020248

APA StyleLi, T., Li, X., Wu, H., & Chen, Q. (2026). Design of a Recyclable Photoresponsive Adsorbent via Green Synthesis of Ag Nanoparticles in Porous Aromatic Frameworks for Low-Energy Desulfurization. Molecules, 31(2), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020248