1. Introduction

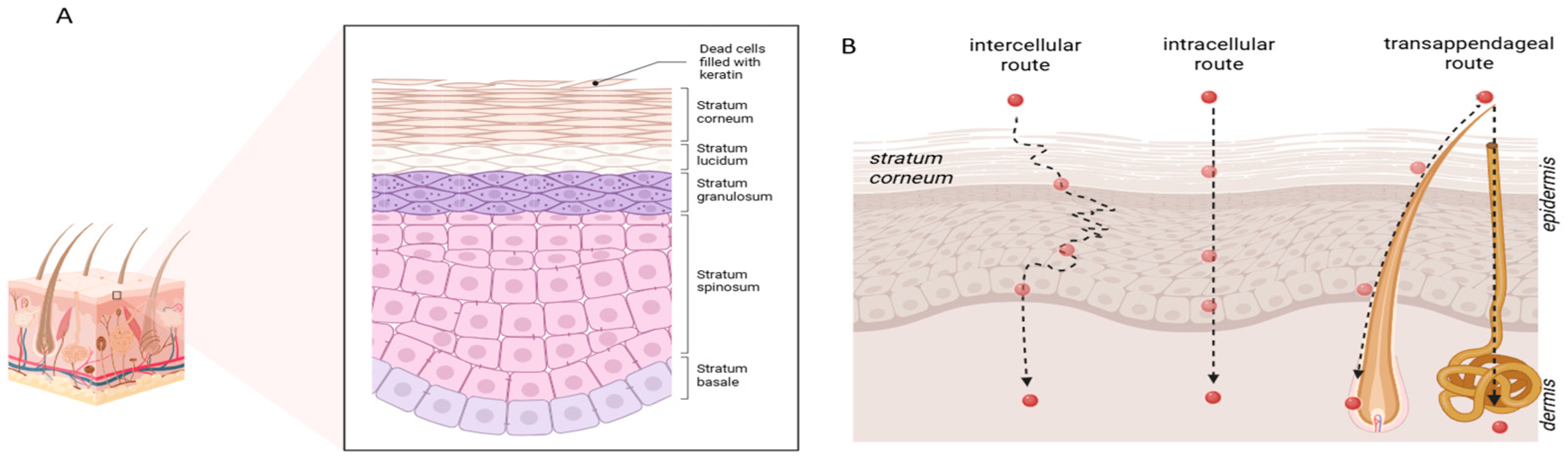

The skin, the largest organ of the human body, functions not only as a sophisticated physical barrier but also as a promising route for drug delivery. Its finely specialised three-layered structure—epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis—protects the body from toxic agents and micro-organisms, while simultaneously offering unique advantages for the systemic administration of active ingredients [

1]. The uppermost layer of the epidermis comprises multiple sublayers, including the stratum corneum (SC), which consists of approximately thirty layers of dead keratinocytes embedded in a lipid-rich matrix. Owing to its composition, the SC represents the rate-limiting barrier for xenobiotic absorption [

2]. Molecules may permeate the skin via either the transepidermal or transappendageal pathways. The former involves intercellular and intracellular routes—favourable to hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules, respectively—while the latter exploits hair follicles and sweat glands, serving as the preferred pathway for large and highly lipophilic compounds (

Figure 1) [

3]. Once a substance permeates beyond the SC, it can readily reach the vascularised dermis, making the accurate measurement of transdermal passage rates (log K

p) essential.

Current methodologies for assessing skin permeability rely mainly on human or animal model membranes, which often suffer from low reproducibility and limited throughput [

4]. Consequently, substantial research efforts are directed toward developing reliable, sustainable, and ethical alternatives to ex vivo skin. In this context, multidimensional analytical techniques have emerged as powerful tools for emulating complex biological barriers. In particular, biomimetic bidimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) has recently gained increasing attention. Biomimetic chromatography uses stationary phases with biological components such as phospholipids or proteins. This allows the chromatographic system to mimic the environments where drug molecules interact, are absorbed, and are distributed [

5]. Multidimensional chromatography increases separation efficiency by combining two often complementary separation mechanisms. In 2D-LC, unresolved compounds from the first dimension (

1D) are transferred to the second (

2D), where differences in selectivity may enable an improved separation.

Several operational modes exist in 2D-LC, including comprehensive (LC × LC) and heart-cutting (LC-LC) approaches. In LC × LC analyses, the entire

1D effluent is injected in small fractions in

2D, requiring rapid 2D separations to preserve

1D resolution [

6]. LC-LC and multiple LC-LC, in contrast, isolate selected fractions for detailed 2D analysis, offering higher resolution, impurity detection and flexible runtime management [

7,

8]. A critical factor in effective

2D separations is orthogonality—the degree of complementarity between the two separation mechanisms. High orthogonality improves coverage of the

2D separation space, though excessive disparity may introduce challenges such as solvent incompatibility and viscosity mismatches [

9].

Building on the potential of multidimensional and biomimetic approaches, recent studies have successfully applied LC × LC to predict human intestinal absorption by coupling biomimetic stationary phases representing distinct biological components [

10]. Inspired by this strategy, the present work aims to mimic the multilayered structure of human skin through an analytical platform based on LC × LC. The system integrates an embedded polar amide column in the

1D, emulating the ceramide-rich SC [

11], with an immobilised artificial membrane (IAM) column in the

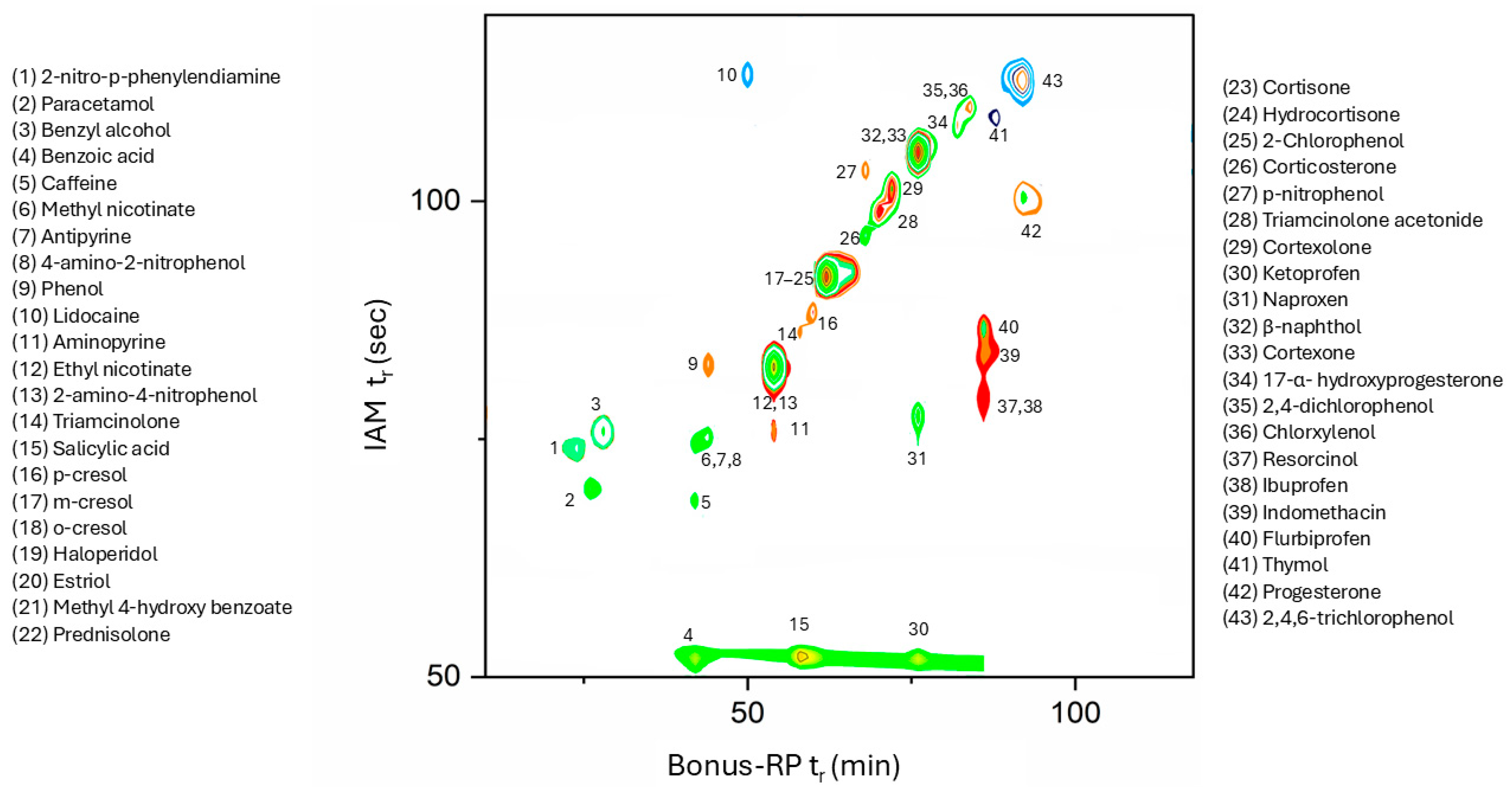

2D, mimicking the phosphatidylcholine-based inner layers. To validate the platform, 43 pharmaceutical and cosmetic ingredients with known log K

p values [

12] were analysed, and relationships between chromatographic affinity indices (log k) and skin permeability were investigated. Additionally, the 2D chromatograms were examined to identify regions containing molecules with distinct permeation properties.

In parallel, we developed an in vitro permeability assay using Permeapad

®, a high-throughput artificial membrane that has been previously validated for assessing passive permeability in gastrointestinal, buccal, and nasal tissues [

13,

14]. Coupled with miniaturised high-throughput chromatography, Permeapad

® enabled the experimental determination of log K

p, which was subsequently compared with literature data and with affinity chromatographic data derived from the biomimetic platform. Furthermore, in silico modelling was performed to develop predictive equations for log K

p, to enhance the standardisation and predictive power of transdermal permeability assessments.

3. Discussion

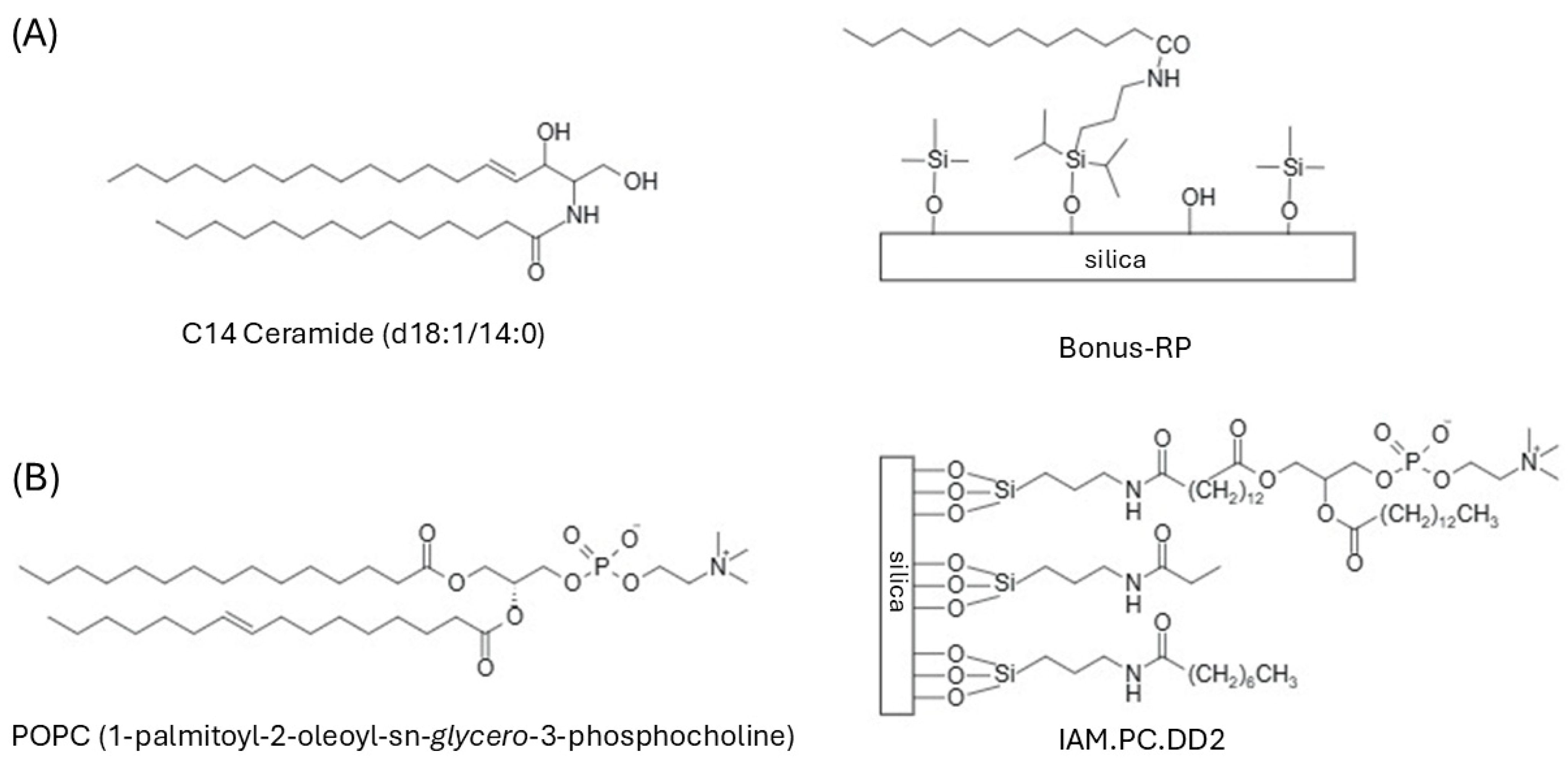

The fully biomimetic platform was designed to capture complementary aspects of transdermal permeation by exploiting chromatographic affinity measurements on biologically inspired stationary phases.

Figure 6 illustrates the analogy between the stationary phases and the biological structures they emulate.

Ceramides, which constitute the major lipidic component of SC, are simple sphingolipids formed by a sphingosine linked to a fatty acid via an amide bond [

11], and their presence in Bonus-RP contributes to its skin-mimicking feature. Zorbax Bonus-RP was selected as a complementary and orthogonal stationary phase due to its ability to retain analytes that are poorly resolved on conventional RP materials, its compatibility with highly aqueous mobile phases, and its chemical similarity to the skin ceramides embedded in the SC [

16].

IAM columns were already exploited to profile the permeation of drug-like molecules through biological membranes [

17,

18,

19], despite being based on a monolayer of a single phospholipid. PC, as the main phospholipid component of cell membranes, closely resembles the surface of a biological cell membrane due to its combination of hydrophobic interactions, ion pairing, and hydrogen bonding interactions.

Chromatographic conditions were adjusted to reflect physiological skin environments as closely as possible: a pH 5.5 buffer in the first dimension to reproduce the acidic outer layers of the skin, and a pH 6.5 buffer in the second dimension to mirror the progressive increase in pH deeper in the epidermis [

20]. However, IAM columns inherently limit method development because of the strict manufacturer guidelines regarding pH, organic modifier, and solvent ratios. For this reason, only conditions that were entirely within the recommended range were used to avoid compromising the integrity of the stationary phase.

Interestingly, compounds exhibiting favourable skin permeation (as indicated by log KpFranz) tend to display moderate (rt > 60 s) retention in the IAM phase and medium-to-high retention (rt > 45 min) on the Bonus RP column, suggesting the presence of a potential retention cut-off across the two-dimensional platform. Notably, ketoprofen behaves as an outlier on the IAM column, despite being among the most strongly retained compounds in the Bonus RP phase. These observations support the relevance of combining the two chromatographic dimensions to capture distinct molecular interaction profiles associated with transdermal permeability.

Although these results must be seen as preliminary, the potential of this platform lies in the aspect that analytes’ permeability could be profiled in a rapid and reliable way only by looking at the position the compound’s signal occupies in the 2D-LC chromatogram, thus avoiding complex mathematical modelling. Additionally, the fact that 2D-LC can also be used for quantitative analysis paves the way for applying the same experiment for different purposes e.g., dermal permeability assessment, QC, and degradation studies.

Permeability measurements were obtained using Permeapad

®, a biomimetic membrane consisting of a phospholipid layer (soybean phosphatidylcholine S-100) enclosed between cellulose sheets to prevent lipid leakage [

21]. Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between the permeability of Permeapad

® and results from Caco-2 or PAMPA assays [

14,

22], supporting its suitability for modelling passive diffusion. Although Magnano et al. 2022 [

23] pointed out certain limitations of the classical Permeapad

® membrane in fully mimicking the skin barrier, no more accurate alternatives—such as the ceramide and cholesterol-enriched version— were available at the time the experiments were conducted. It is nevertheless important to note that phosphatidylcholine, which constitutes the Permeapad

® membrane, is itself an essential component of the lipid matrix, providing a physiologically relevant environment that supports its use as a surrogate skin membrane.

Analysing the chromatographic data, a clear relationship was observed between log P and log k on Bonus-RP, indicating that analytes were separated according to their lipophilicity. However, plotting log k

Bonus-RP against the permeability coefficients obtained through Permeapad

® revealed no discernible correlation. Given the complexity of the skin and the variety of potential permeation routes, including the aqueous pore pathway [

24], it is unsurprising that

n-octanol/water lipophilicity alone cannot explain transdermal passage [

25].

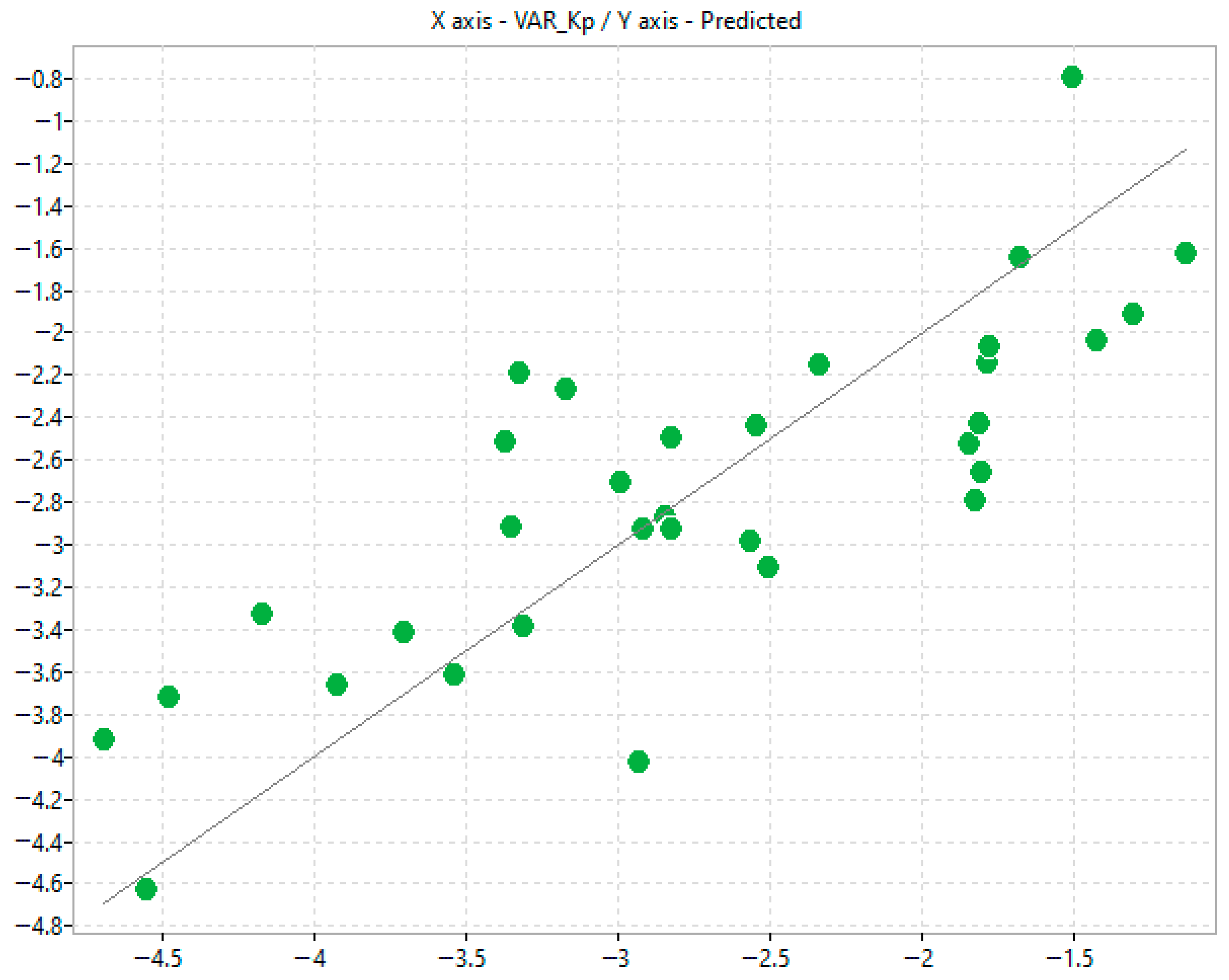

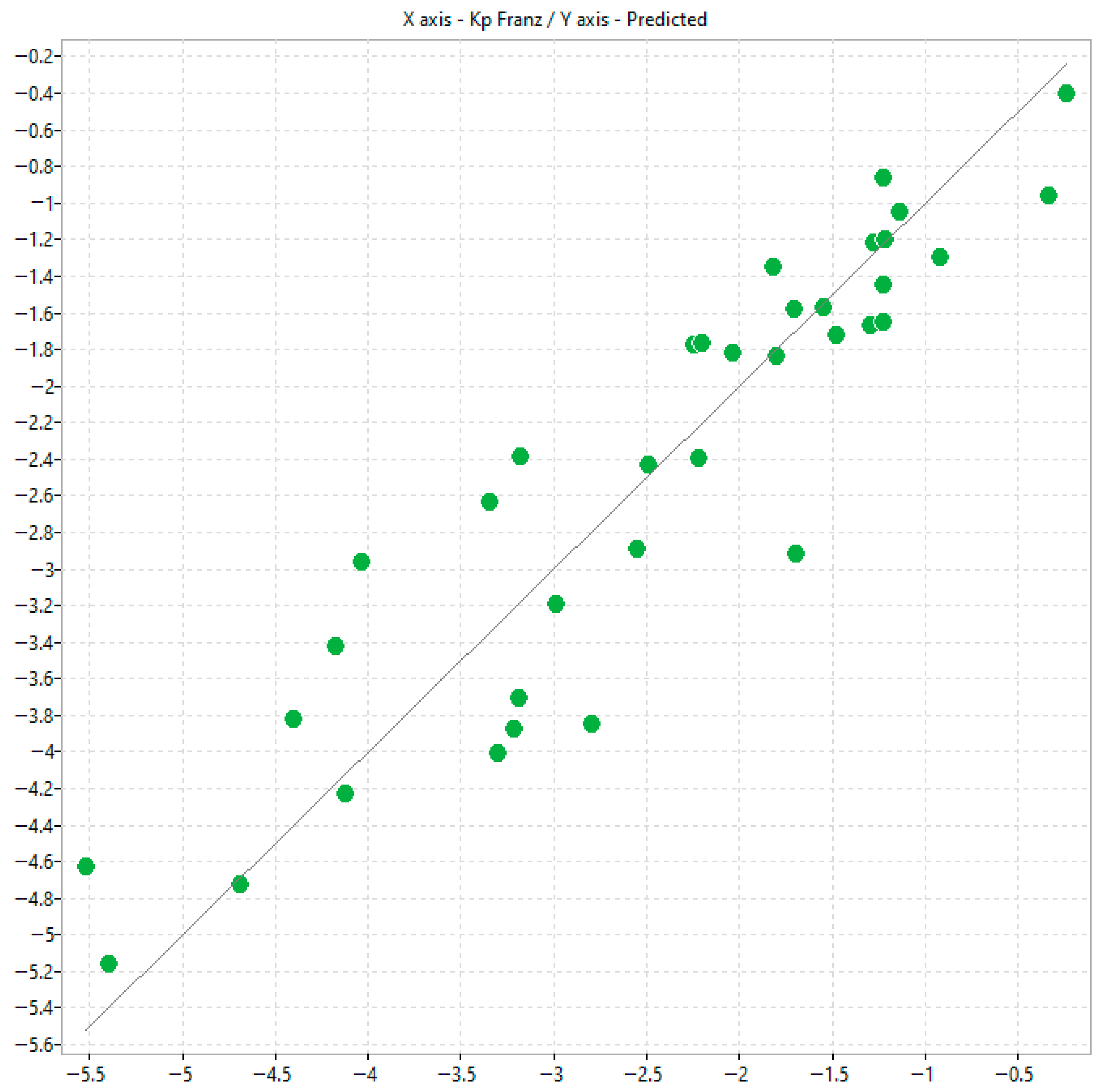

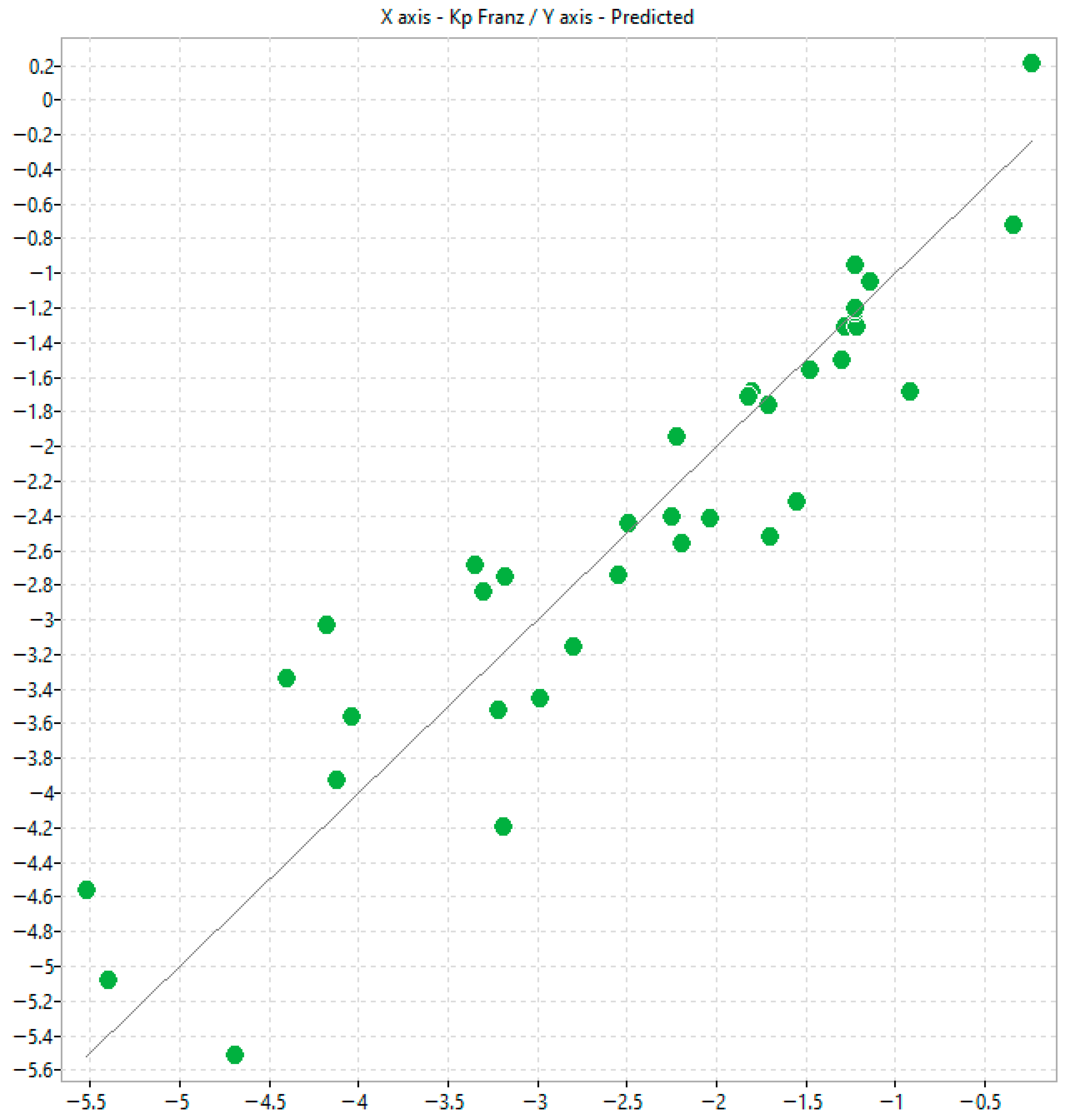

The in silico modelling provided some usefulness in estimating permeability coefficients using both chromatographic and mass diffusion indices. The selected physico-chemical descriptors are often complex and represent a blend of topological, electrostatic and other molecular property parameters, making mechanism elucidation challenging. However, some useful information can still be drawn. For instance, in model 3, n-octanol/water lipophilicity, i.e., ALOGP2, relates positively with transdermal passage consistently implying that the more lipophilic the solute, the greater the transdermal passage observed. In addition, Chi1_AEA (dm) is a connectivity-like index which depends on complex molecular attributes including, but not limited to, overall molecular dipole moment, dipole density distribution and charge separation efficiency. This descriptor relates negatively to transdermal passage suggesting that ample clusters of polar bonds or electronic heterogeneity hinder transdermal passage.

Scatter plots correlating log k

IAM.MG.DD2 with permeability coefficients (K

p) obtained using Permeapad

® similarly showed only a weak relationship. The trend was even poorer for K

p values derived from Franz diffusion cell (FDC) studies [

12], which are inherently affected by biological variability in excised skin tissues. These results support the hypothesis that, although the polar headgroups of IAM phases accurately mimic natural biomembranes, the permeation process is governed by a more intricate interplay of interactions than cannot be recapitulated by a single phospholipid monolayer. IAM lacks the multilayered, ceramide-rich organisation characteristic of skin, while Permeapad

® represents a bilayer but does not replicate the lipid heterogeneity of the stratum corneum. Moreover, IAM may insufficiently capture phospho-hydrophobic interactions in ionisable molecules.

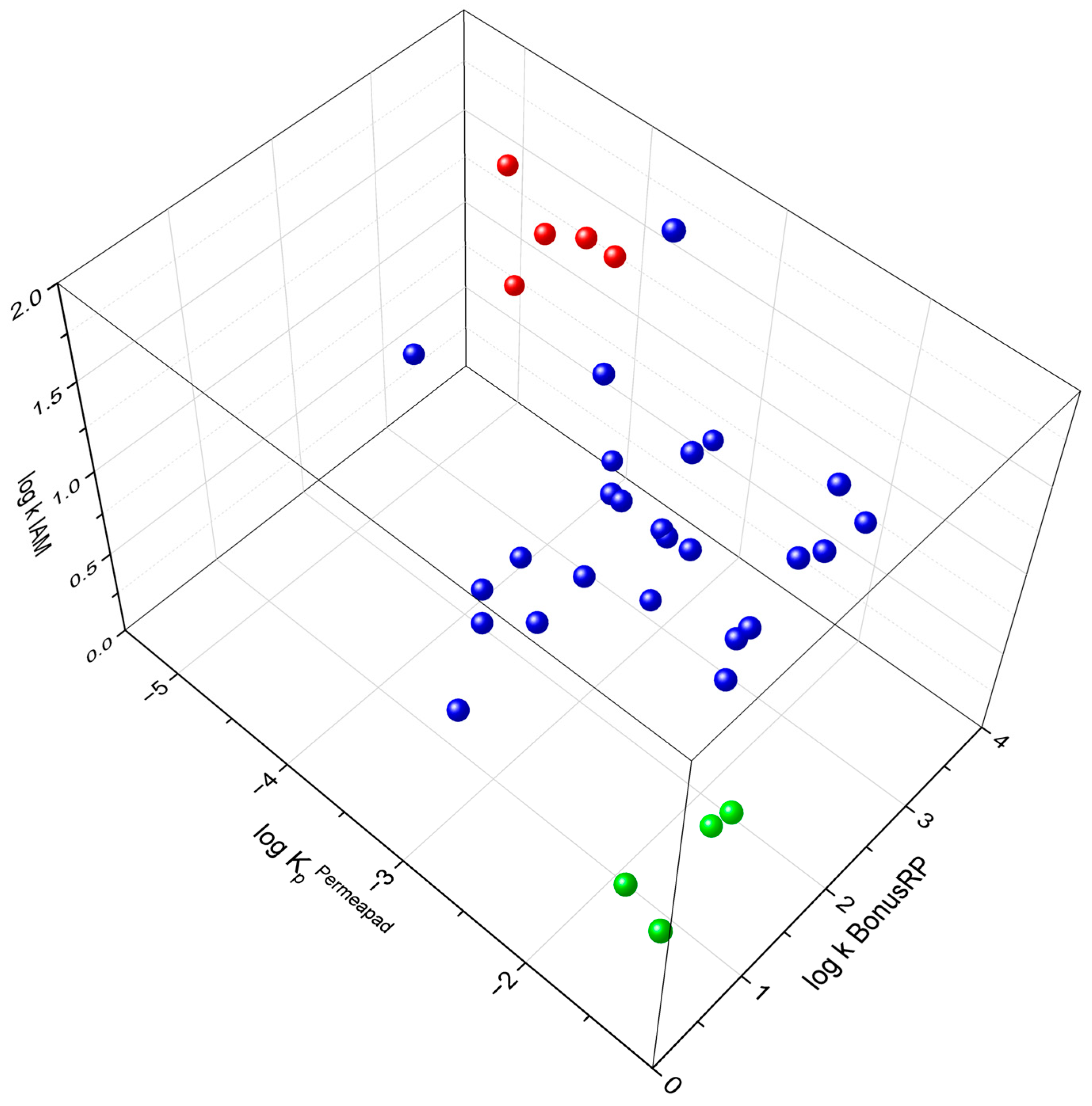

Despite the absence of linear correlations, when the three experimental parameters were plotted together in a three-dimensional space (

Figure 7), well-defined clusters emerged. These regions group compounds that display similar affinity patterns and comparable permeability. This multidimensional distribution demonstrates that the combined interpretation of affinity and permeability values captures trends that are not visible through pairwise comparisons alone. Such integration underscores the importance of intersecting multiple dimensions to reconstruct the multifactorial nature of skin permeation.

In this context, the platform provides added value by enabling qualitative classification of compounds based on their combined chromatographic and permeability behaviour. Overall, our findings demonstrate that while chromatographic and permeation assays independently offer only partial representations of the skin barrier, their integration, supported by modelling, provides a more holistic and fully integrated perspective. Compared with conventional dermal permeability assessment methods, which are often low-throughput, material-intensive, and dependent on complex biological models, the proposed workflow is designed as a high-throughput, microscale screening strategy suitable for early-stage compound prioritisation. In particular, the LC × LC platform, combining two stationary phases with different selectivity, enhances peak capacity and orthogonality, resulting in improved chromatographic resolution and reduced matrix effects. This enables more sensitive detection of trace components and supports a rapid, information-rich evaluation of compound–barrier interactions, thereby strengthening the platform’s potential as a screening and decision-support tool for the early evaluation of candidates for transdermal administration.