In Silico and In Vitro Insights into the Pharmacological Potential of Pouzolzia zeylanica

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

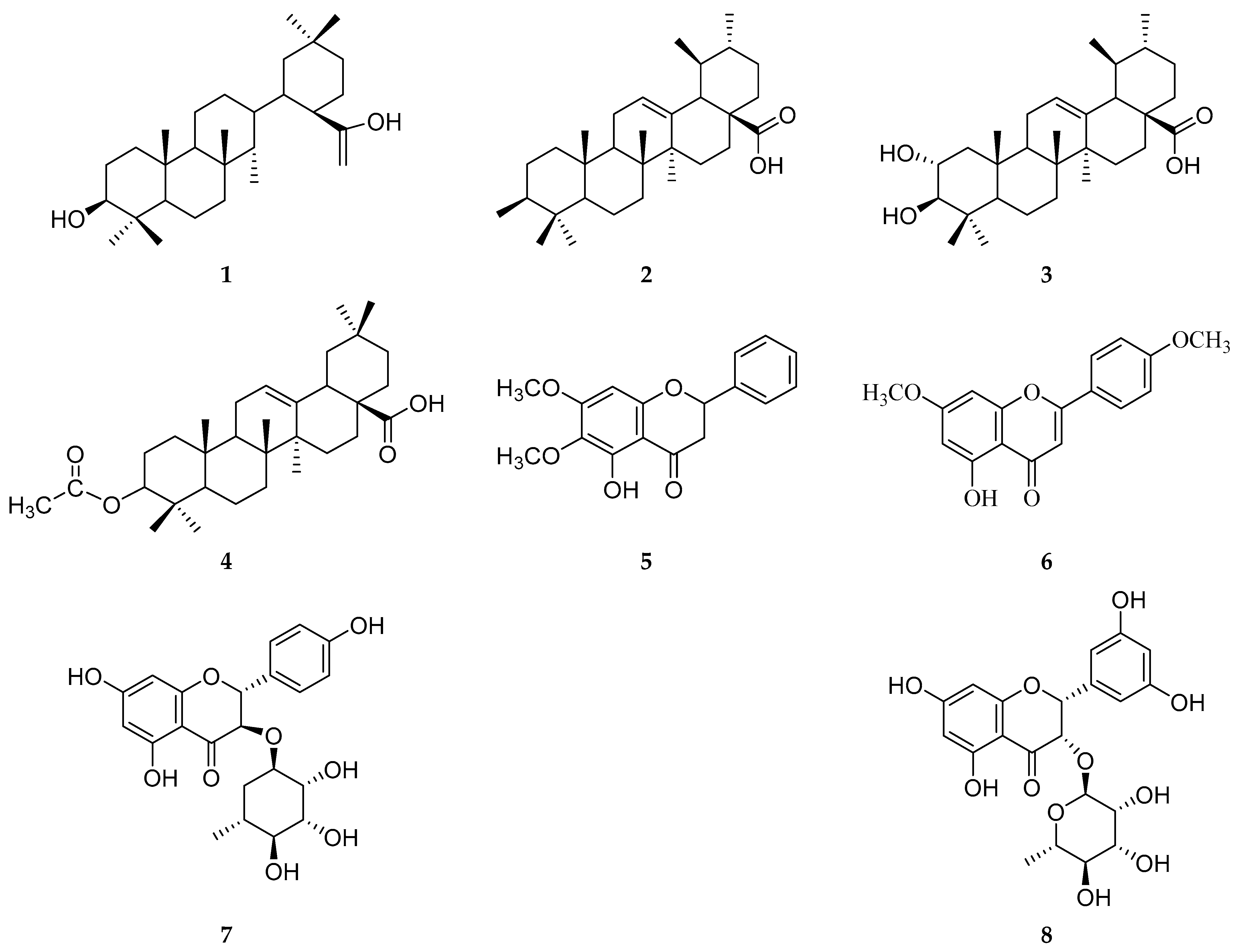

2.1. Chemical Constituents of P. zeylanica

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

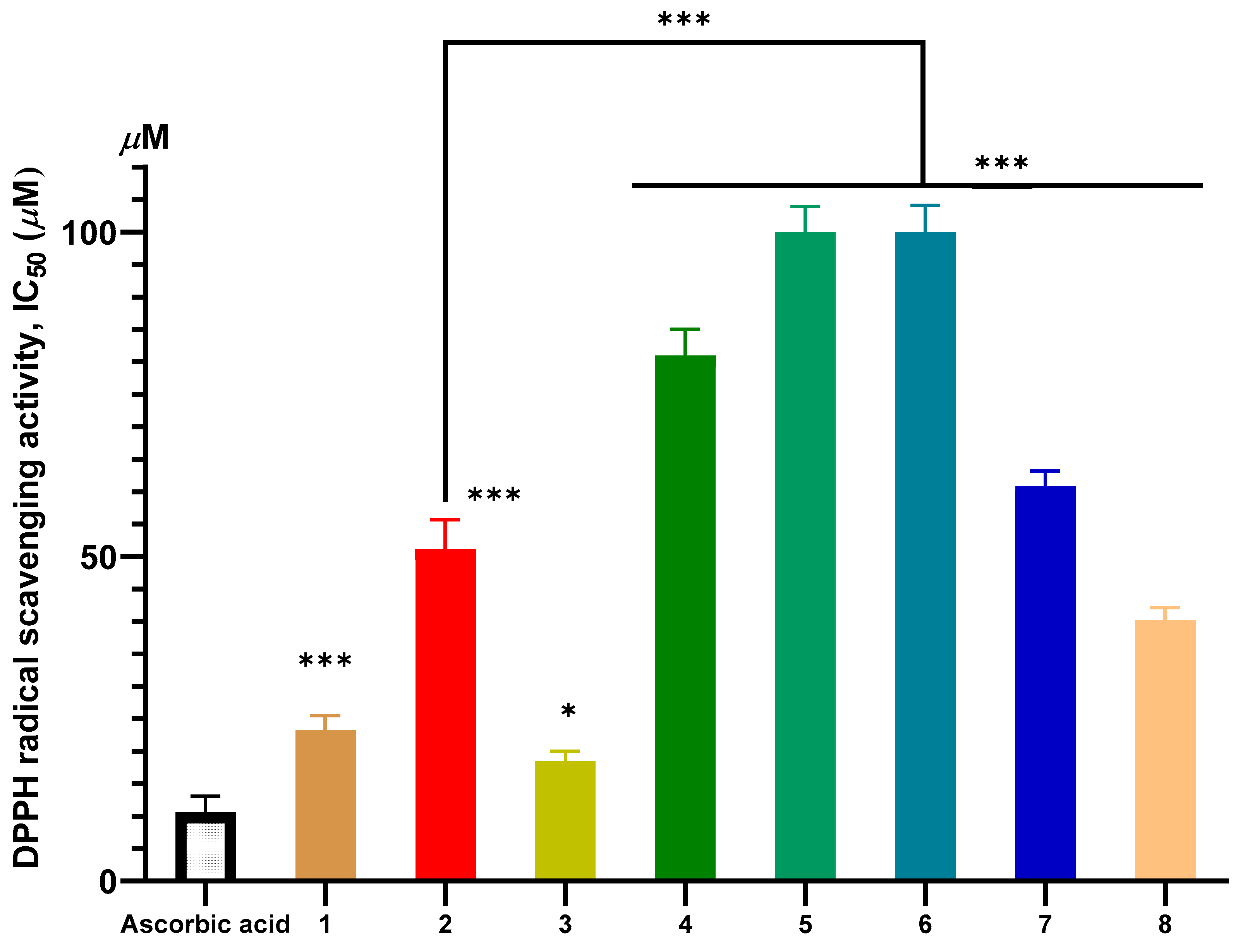

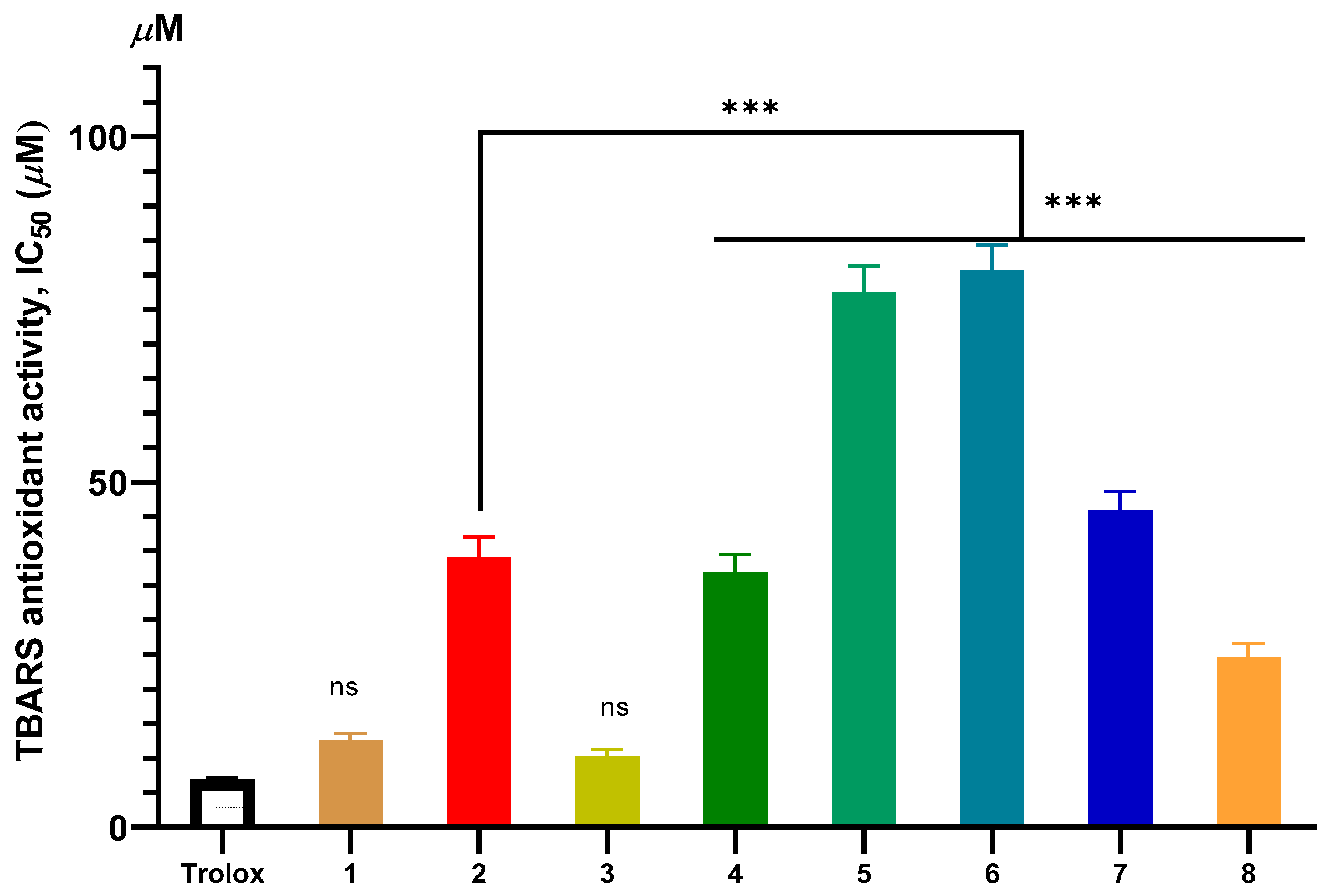

2.2.1. In Vitro Antioxidant Evaluation

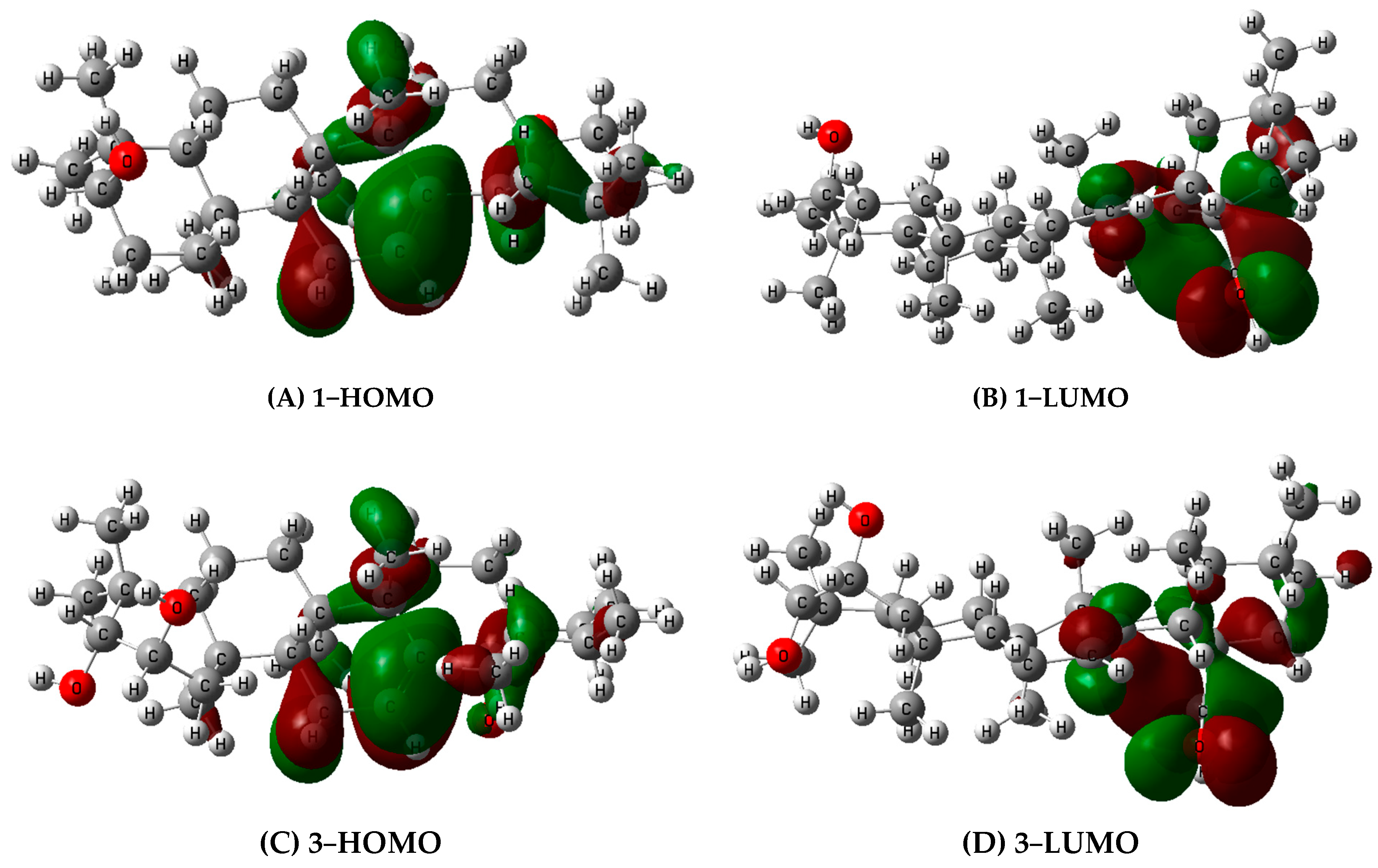

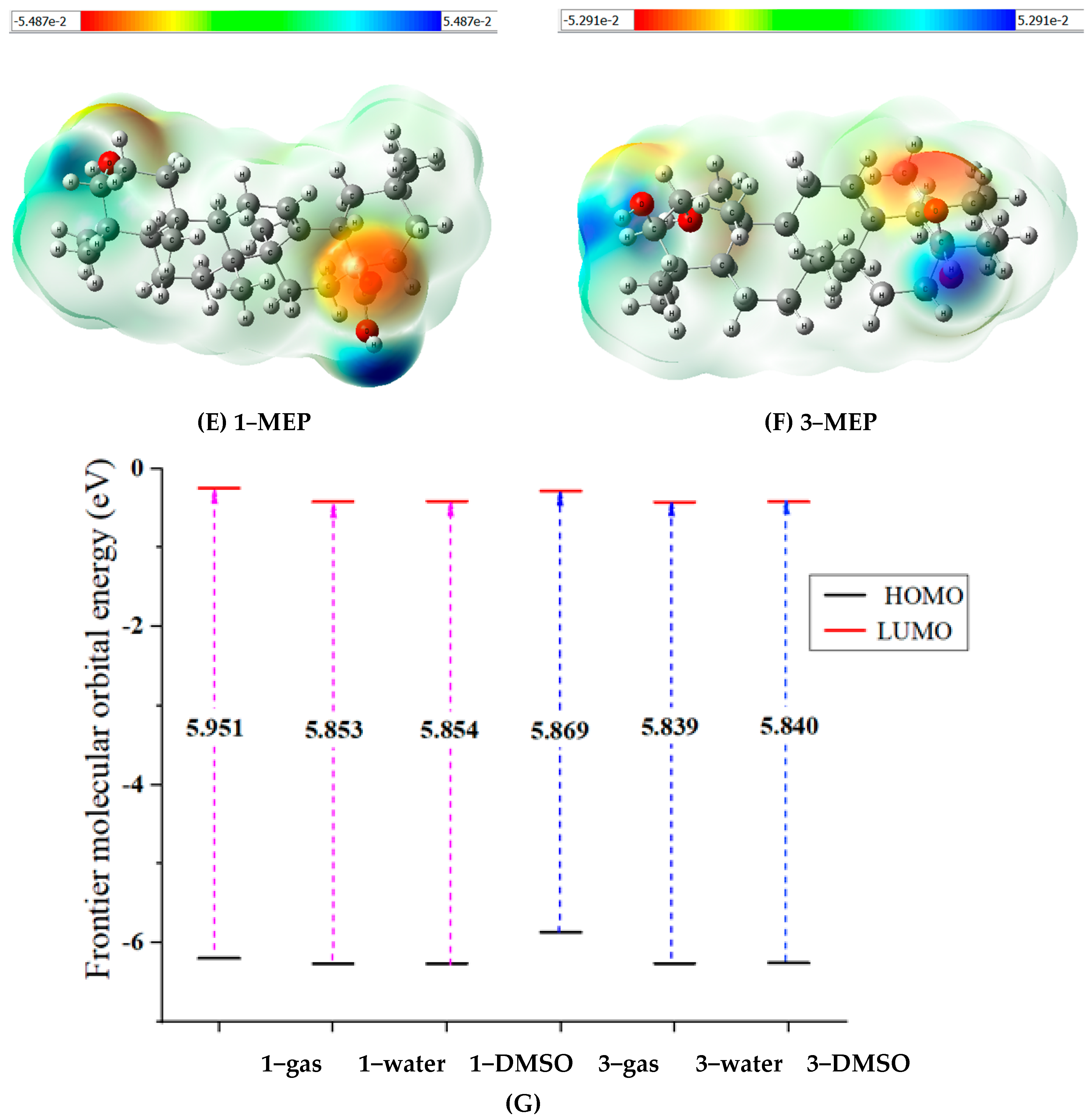

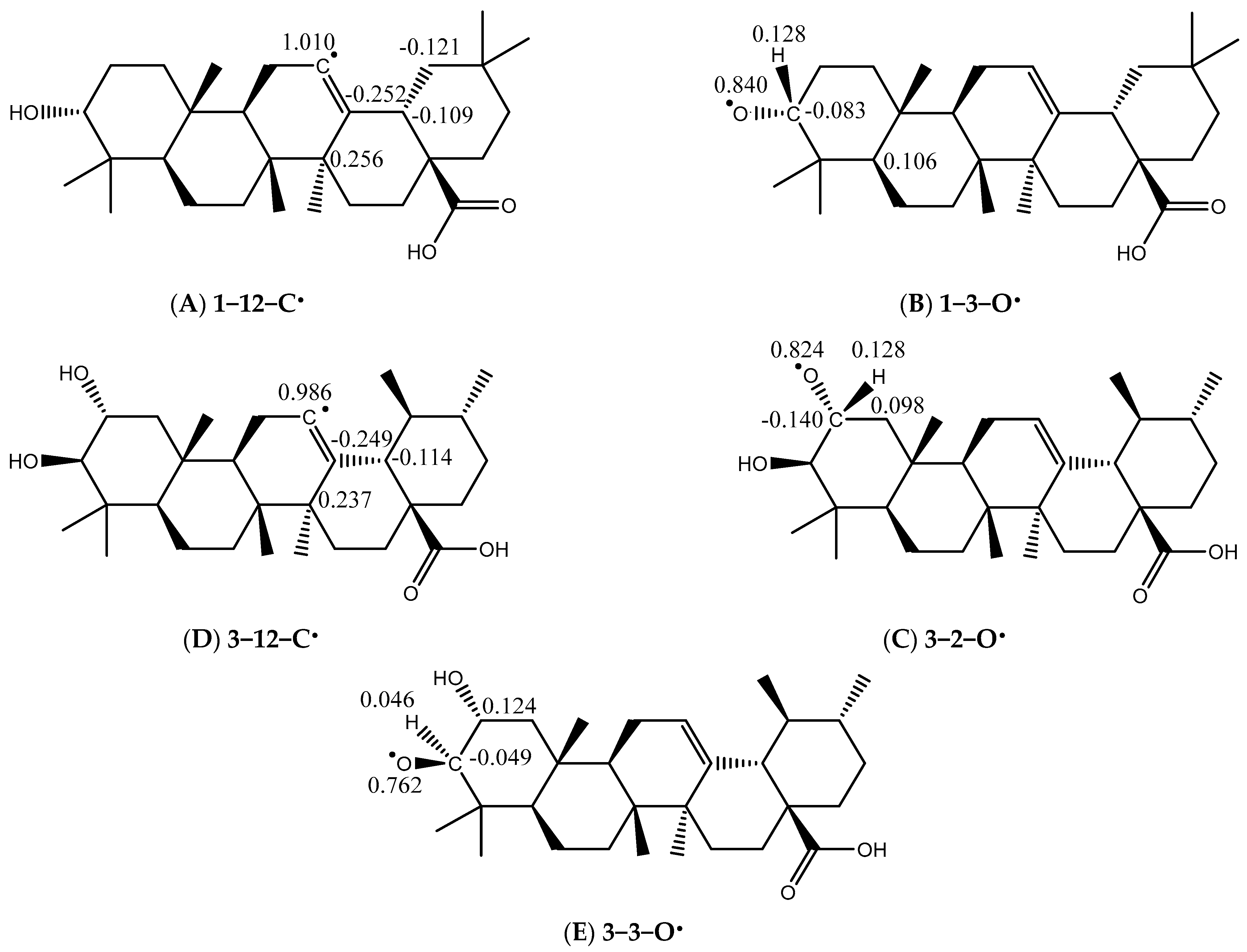

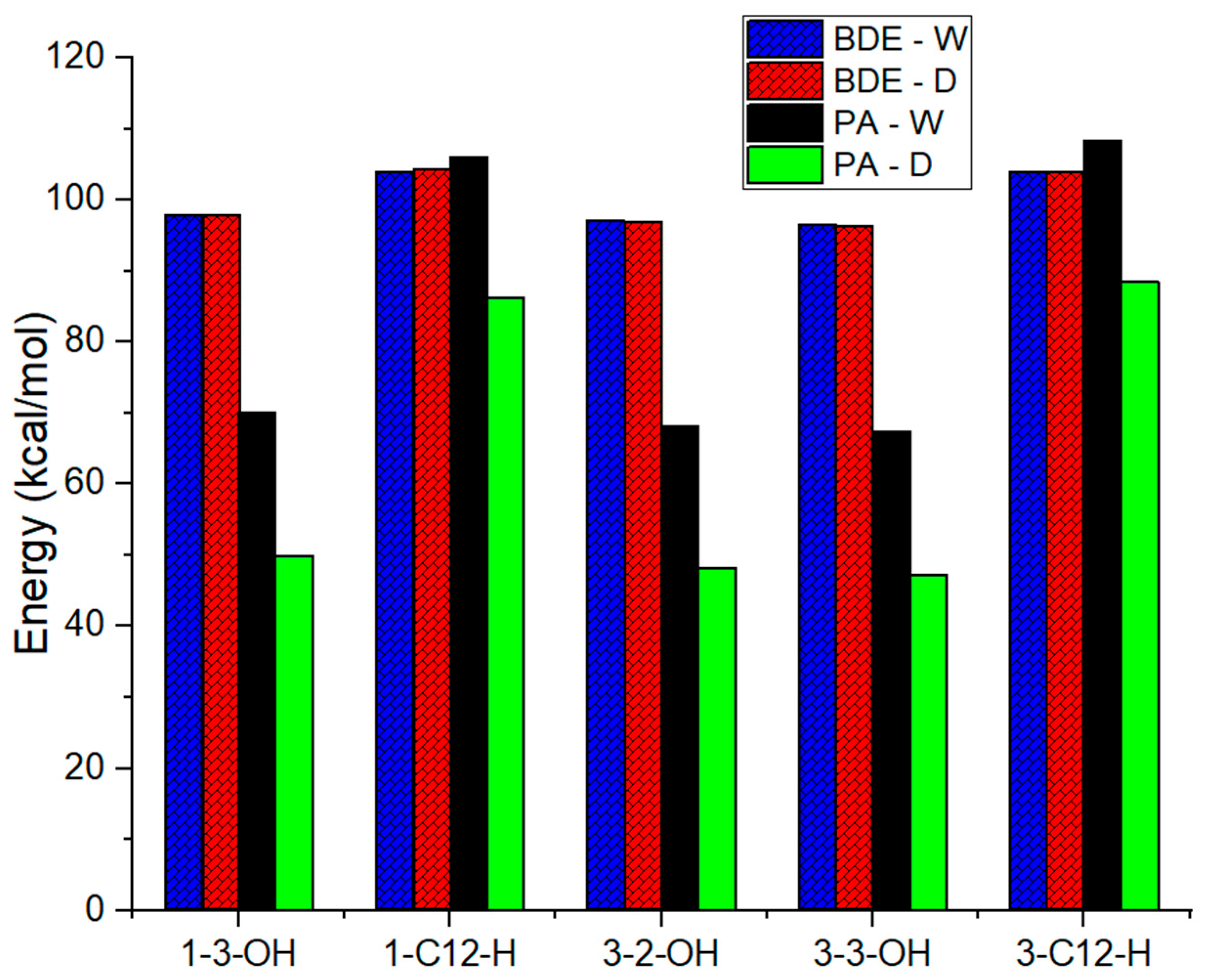

2.2.2. The Antioxidant Activity in Silico

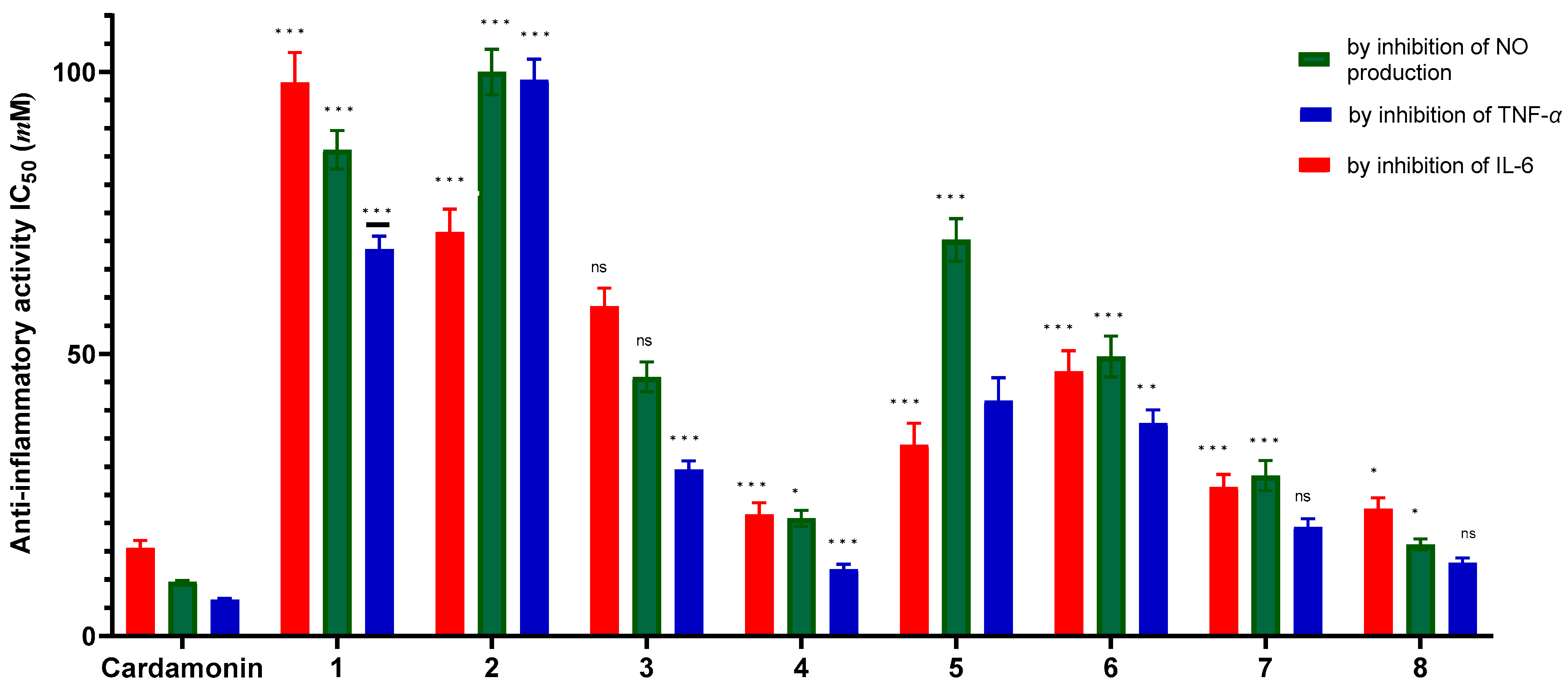

2.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

2.3.1. In Vitro Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation

2.3.2. In Silico Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Targets

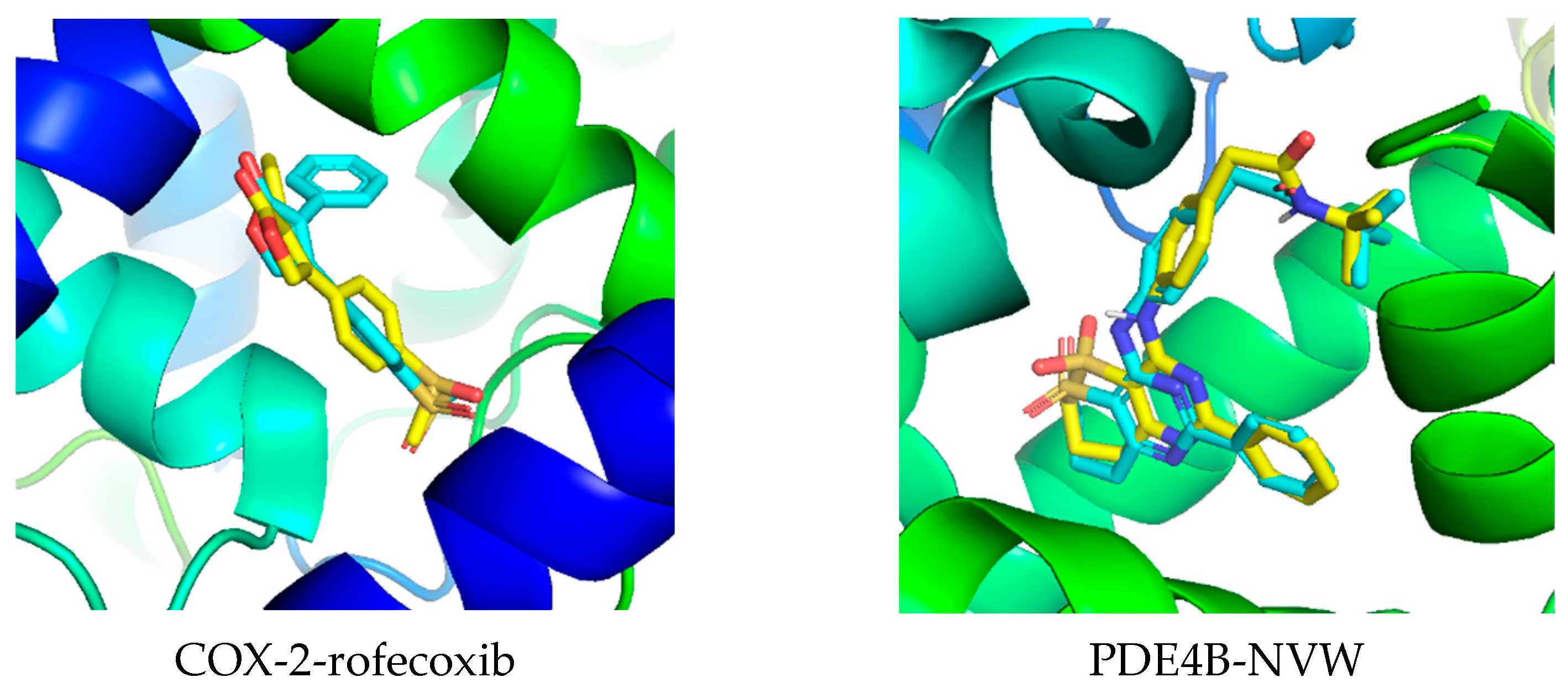

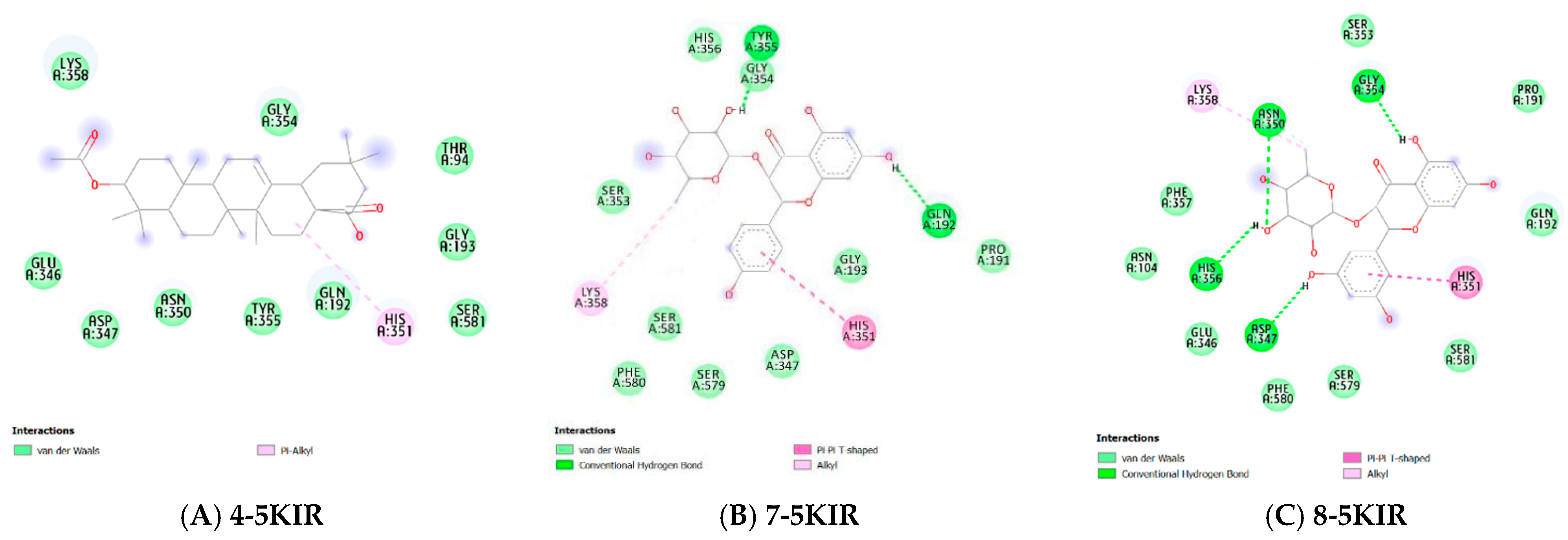

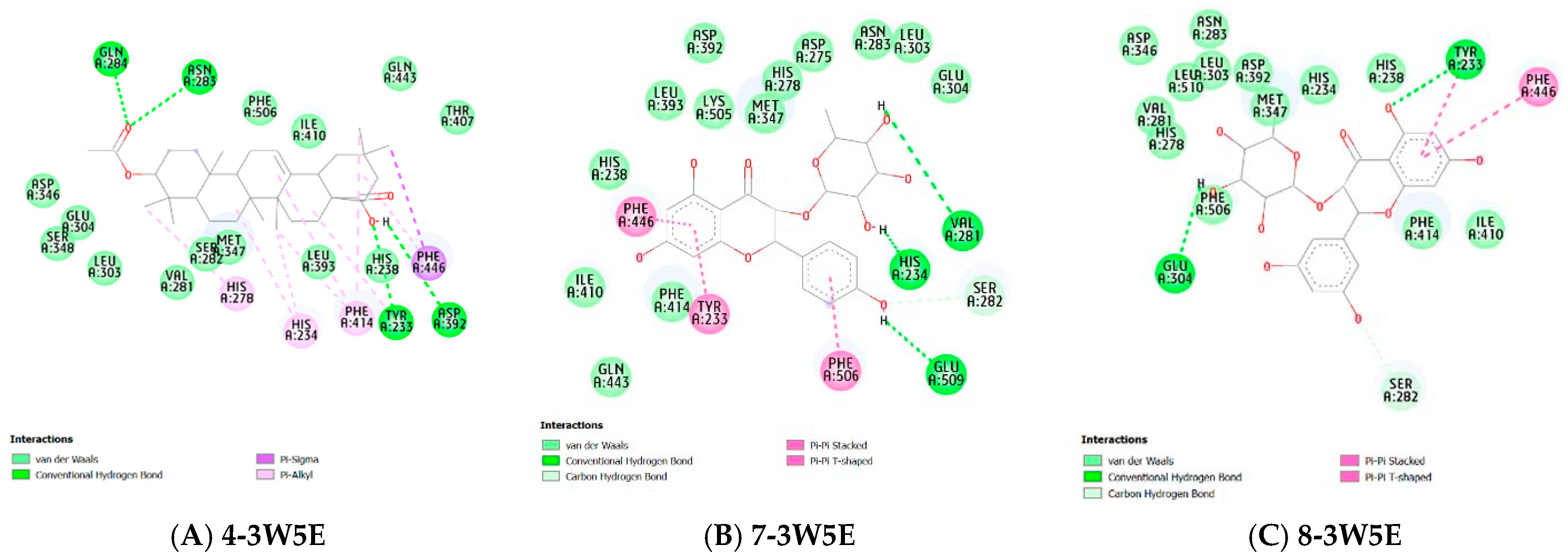

Molecular Docking

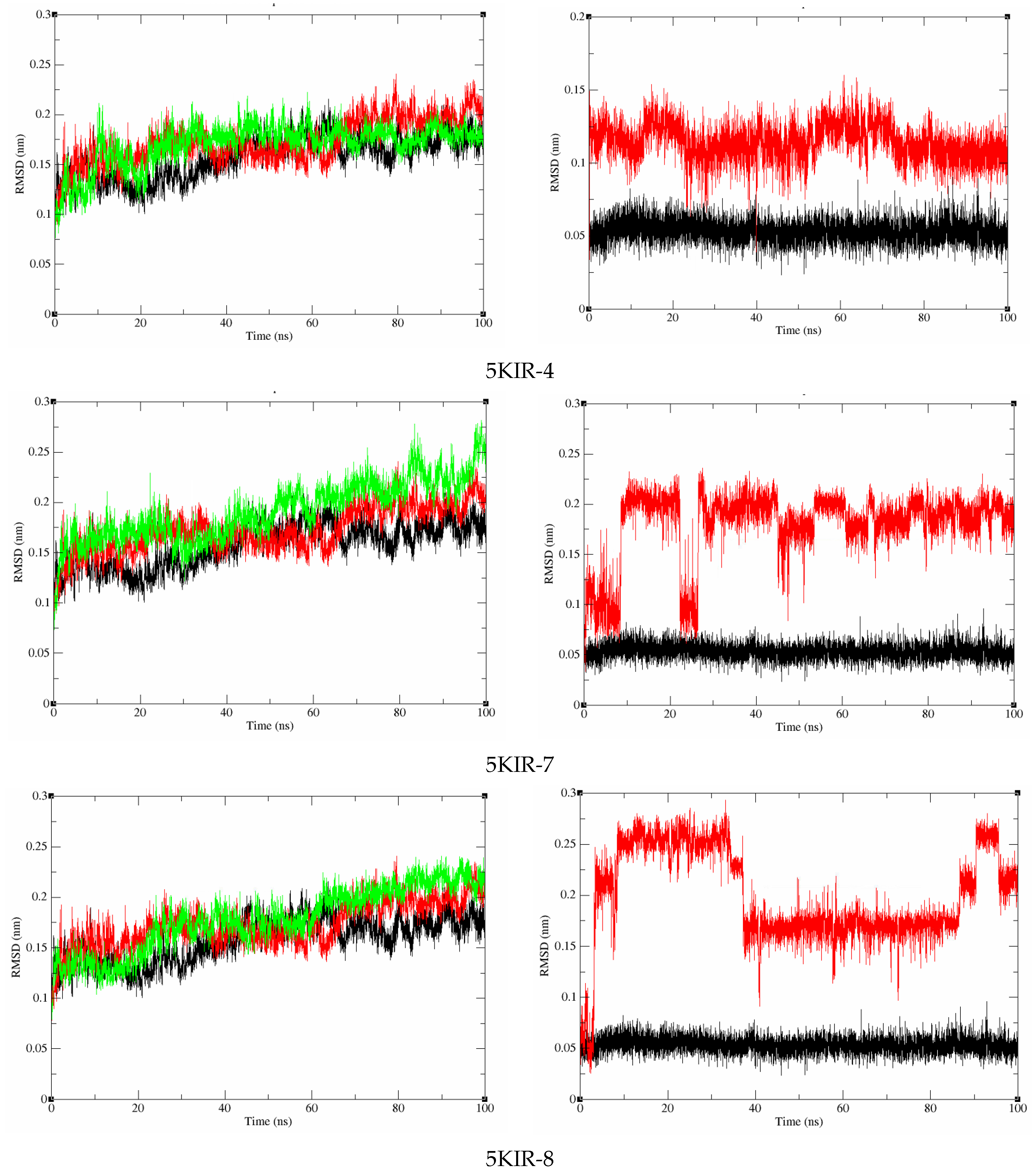

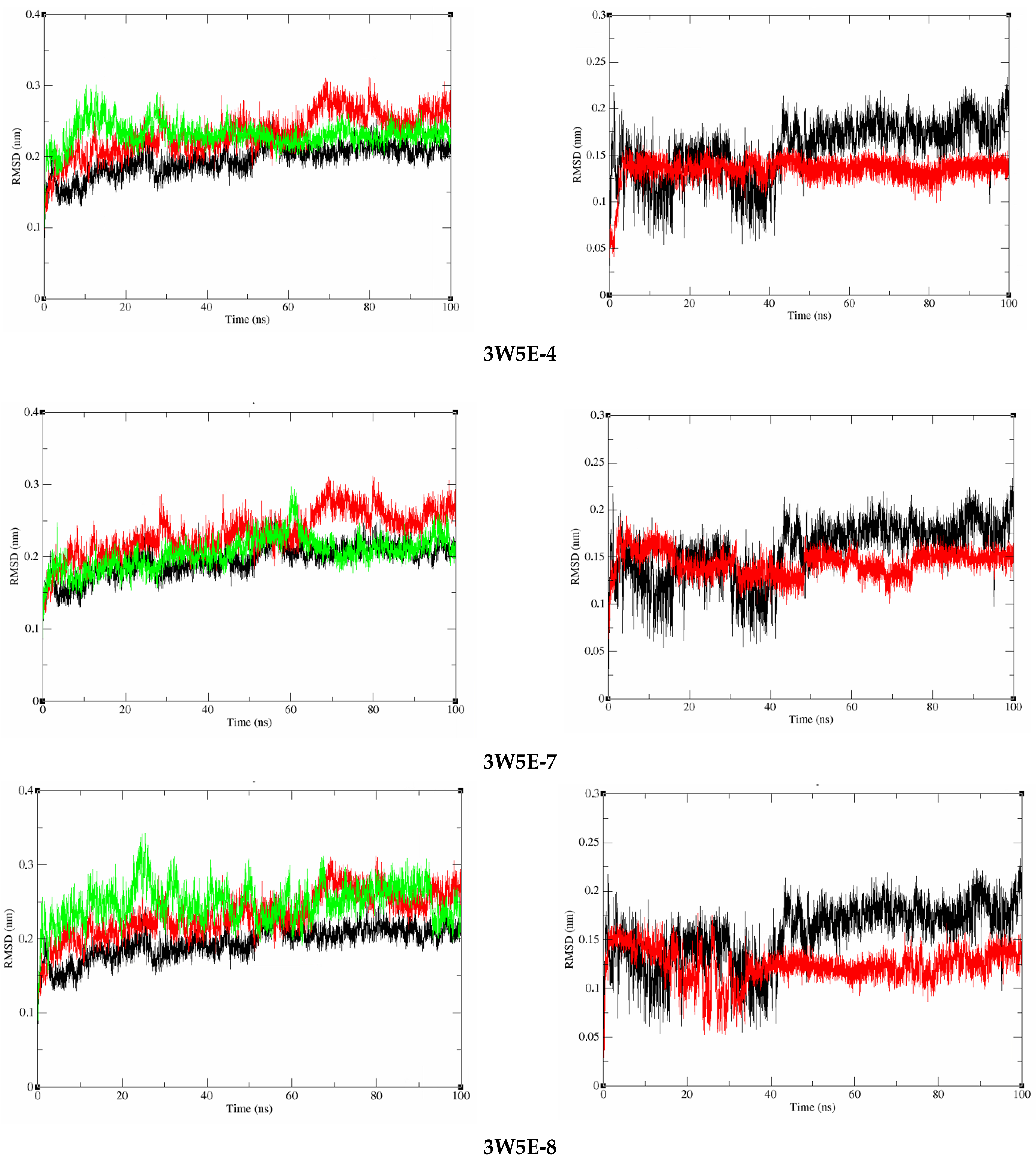

Molecular Dynamics

3. Materials, Methods and Experimental

3.1. Plant Materials

3.2. Methods of Isolation and Structure Determination of Compounds

3.3. Experiment and Separation

3.4. Computational Methods

3.4.1. DFT Calculation

3.4.2. Molecular Docking

3.4.3. Molecular Dynamics

3.5. Antioxidant Assay

3.5.1. In Vitro DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

3.5.2. Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition Assay (TBARS Method)

3.5.3. Data Analysis for Antioxidant Assays

3.6. Cell Culture

3.7. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Activity via NO Production Assay

3.8. Assessment of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion

3.9. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahsan, M.; Alam, M.; Chowdhury, M.; Nasim, M.; Islam, S. In vitro and In vivo Evaluation of Pharmacological Activites of Pouzolzia sanguinea. J. Bio Sci. 2021, 29, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Aktulga, H.M.; Belfon, K.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cisneros, G.A.; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Forouzesh, N.; Giese, T.J.; Götz, A.W.; Gohlke, H.; et al. AmberTools. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2023, 63, 6183–6191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Isolation and characterization of novel flavonoids from Pouzolzia zeylanica with α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. Phytochem. Lett. 2022, 48, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.H.; Zhang, H.; Tao, S.H.; Luo, Z.; Zhong, C.Q.; Guo, L.B. Norlignans from Pouzolzia zeylanica var. microphylla and their nitric oxide inhibitory activity. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 17, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Bora, K. Antimicrobial activity of Pouzolzia zeylanica against clinically significant pathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 672–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.N.; Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Q.; Tang, G.Y.; Gan, Y.; Li, H.B. Insight into the roles of vitamins C and D against cancer: Myth or truth? Cancer Lett. 2018, 431, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huy, N.M.; Thanh, N.V.; Vy, V.N.T.; Giau, T.N.; Tien, V.Q.; Tai, N.V.; Minh, V.Q. Optimization of the extraction of bioactive compounds from Pouzolzia zeylanica using Box-Behnken experimental design and application in the preparation of mixed juice. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, e27123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M.; Li, Z.H.; Tao, S.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Chen, Z.H.; Guo, L.B. Effect of FPZ, a total flavonoids ointment topical application from Pouzolzia zeylanica var. microphylla, on mice skin infections. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2018, 28, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, N.A.; Hop, N.Q.; Tam, H.T.M.; Thuy, Q.C.; Linh, Q.V.; Linh, N.N.; Le, V.T.T. Chemical composition and invitro anti-flammatory activity of Pouzolzia zeylanica in Vietnam. TNU J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 229, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.P.; Son, K.H.; Chang, H.W.; Kang, S.S. Anti-inflammatory plant flavonoids and cellular action mechanisms. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2004, 96, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmot-Dear, C.M.; Friis, I. The old world species of Pouzolzia (Urticaceae, tribus Boehmerieae). A taxonomic revision. Nord. J. Bot. 2004, 24, 5–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.P.; Hoa, T.K.; Sang, V.T.; Na, L.T.S. Effect of blanching and drying to production of dried herbal tea from Pouzolzia zeylanica. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 11, 1437–1440. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Lee, J.S.; Park, K.D.; Ching, Y.C.; Nguyen, X.T.; Phan, V.G.; Thi, T.T.H. Green silver nanoparticles formed by Phyllanthus urinaria, Pouzolzia zeylanica, and Scoparia dulcis leaf extracts and the antifungal activity. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, V.H.; Nguyen, T.K.O.; Le, M.T. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pouzolzia zeylanica leaf extract: Characterization and antifungal evaluation. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 276, 125402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, P.K.N.; Linh, T.C.; Long, V.H.; Trang, D.T.X. Isolation and evaluation of antibacterial activity of endophytic bacterial strains in Pouzolzia zeylanica L. TNU J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 228, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.A.; Tran, C.L.; Tran, T.T.T.; Do, P.Q. Evaluating anti-bacterial and antioxidant activities of extracts from Pouzolzia zeylanica L. leaves and stems. Can Tho Univ. J. Sci. 2017, 52, 29–36. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Tariquzzaman, M.; Isla, M.R.; Susmi, T.F.; Rahman, M.S.; Rahi, M.S. Plant-derived Bisphenol C is a drug candidate against Nipah henipavirus infection: An in-vitro and in-silico study of Pouzolzia zeylanica (L.) Benn. In Silico Pharmacol. 2025, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, G.A. Endophytes as sources of bioactive products. Microbes Infect. 2003, 5, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouda, S.; Das, G.; Sen, S.K.; Shin, H.S.; Patra, J.K. Endophytes: A treasure house of bioactive compounds of medicinal importance. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Vo, T.X.T.; Nguyen, M.T. Bioactive compounds, pigment content and antioxidant activity of Pouzolzia zeylanica plant collected at different growth stages. CTU J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 54, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Le, Q.V.; Vo, T.T.; Nguyen, M.T. Optimization of polyphenol, flavonoid and tannin extraction conditions from Pouzolzia zeylanica L. benn using response surface methodology. CTU J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 05, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Prasad, D.; Maithani, R.; El Ibrahimii, B. Corrosion inhibition assessment of a sustainable inhibitor from the weed plant (Pouzolzia zeylanica L.) on SS-410 surface in 0.5 M HCl acidic medium. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 165, 105693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swati Paul, S.P.; Dibyajyoti Saha, D.S. In vitro screening of cytotoxic activities of ethanolic extract of Pouzolzia zeylanica (L.) Benn. Int. J. Pharm. Innov. 2012, 2, 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Asanga, E.E.; Joseph, A.; Umoh, E.A.; Ekeleme, C.M.; Okoroiwu, H.U.; Edet, U.O.; Umoafia, N.E.; Eseyin, O.A.; Nkang, A.; Okokon, J.E.; et al. New perspectives on the therapeutic potentials of bioactive compounds from Curcuma longa: Targeting COX-1 & 2, PDE-4B, and antioxidant enzymes to counteract oxidative stress and inflammation. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2024, 19, 1934578X241255508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.X.; Le, V.T.T.; Quan, P.M.; Dat, V.T. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory compounds isolated from Millettia dielsiana Harms ex Diels by molecular docking method. Vietnam J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 60, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang Minh Chau, C.; Thi Tra Giang, N.; Thi Thuy Tram, N.; Thi My Chau, L.; Xuan Ha, N.; Thi Thuy, P. In silico molecular docking and molecular dynamics of Prinsepia utilis phytochemicals as potential inhibitors of phosphodiesterase 4B. J. Chem. Res. 2024, 48, 17475198241305879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.L.; Wang, S.F.; Xiao, J.J.; Li, B. Theoretical Study of the Antioxidant Activity of Some Naturally Occurring Flavonoids. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 991, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, P.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Song, P.; Li, Y. Theoretical and experimental study on spectra, electronic structure and photoelectric properties of three nature dyes used for solar cells. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 247, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossen, L.J.; Koley, D.; Hermann, H.L.; Thiel, W. The palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of carboxylic anhydrides with arylboronic acids: A DFT study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11102–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, T.; Sharma, P.; Joshi, T.; Chandra, S. In silico screening of anti-inflammatory compounds from Lichen by targeting cyclooxygenase-2. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020, 38, 3544–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.T.; Hung, H.V.; Ha, N.X.; Le, C.H.; Minh, P.T.H.; Lam, D.T. Natural Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors with Potential Anti-inflammatory Activities from Millettia dielsiana. Molecules 2023, 28, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, T.A.; Al-Amri, S.M. Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) as a Target of Anticancer Agents: A Review of Novel Synthesized Scaffolds Having Anticancer and COX-2 Inhibitory Potentialities. Molecules 2022, 27, 8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limcharoen, S.; Pholpramool, P.; Srisung, R.; Kungwan, N. Computational Analysis and Biological Activities of Oxyresveratrol Analogues, the Putative Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors. Molecules 2022, 27, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nema, M.; Gaurav, A.; Lee, V.S. Docking based screening and molecular dynamics simulations to identify potential selective PDE4B inhibitor. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Marahatha, R.; Basnet, S.; Regmi, B.P.; Katuwal, S.; Dahal, S.R.; Sharma, K.R.; Adhikari, A.; Basnyat, R.C.; Parajuli, N. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation of Several Flavonoids Predict Cyanidin as an Effective Drug Candidate against SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 1, 3742318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.M.; El-Din, M.A.; El-Demerdash, A.M. Rational Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Pyrazole Derivatives as Potential PDE4 Inhibitors and Anti-inflammatory Agents. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1249, 131580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palu, D.; Bighelli, A.; Casanova, J.; Paoli, M. Identification and quantitation of ursolic and oleanolic acids in Ilex aquifolium L. leaf extracts using 13C and 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Molecules 2019, 24, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, S.; Hassan, S.I.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Shaheen, F.; Ghayur, M.N.; Gilani, A.H. Triterpenoids from the leaves of Psidium guajava. Phytochemistry 2002, 61, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shai, L.J.; McGaw, L.J.; Aderogba, M.A.; Mdee, L.K.; Eloff, J.N. Four pentacyclic triterpenoids with antifungal and antibacterial activity from Curtisia dentata (Burm. f) CA Sm. leaves. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 119, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, C.M.; Pinto, P.R.; Nascimento, C.C.H.; De Vasconcelos, S.D.D.; Azevedo, L.A.C.; Stephens, P.R.S.; Nogueira, R.I.; Saranraj, P.; Dire, G.F.; Pinto, A.C. Terpenoids and phytosterols isolated from Plumeria rubra L., form acutifolia (Ait) Woodson and its fungus parasite Colesporium plumeriae. Asian J. Pharm. Res. Dev. 2018, 6, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.T.; Trang, N.T.; Hue, N.T.; Huyen, L.T.; Dat, V.T.; Lam, D.T.; Ha, D.T.N. Flavonoids from Milletia reticulata in Vietnam. TNU J. Sci. Technol. 2022, 228, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.T.; Kao, C.L.; Yeh, H.C.; Song, P.L.; Li, H.T.; Chen, C.Y. A new flavone C-glucoside from Aquilaria agallocha. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eawsakul, K.; Ongtanasup, T.; Ngamdokmai, N.; Bunluepuech, K. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of astilbin contained in Bauhinia strychnifolia Craib. stems: An investigation by in silico and in vitro studies. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliyam, P.; Laphookhieo, S.; Koedrith, P.; Puttarak, P. Antioxidative and anti-cytogenotoxic potential of Lysiphyllum strychnifolium (Craib) A. Schmitz extracts against cadmium-induced toxicity in human embryonic kidney (HEK293) and dermal fibroblast (HDF) cells. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.; Bao, L.; Jiang, T.; Song, K.; Chen, Y.; He, S.; Duan, X.; Ikram, M.; Yang, S.; Rao, M.J. Comparative LC-MS/MS Metabolomics of Wild and Cultivated Strawberries Reveals Enhanced Triterpenoid Accumulation and Superior Free Radical Scavenging Activity in Fragaria nilgerrensis. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Zhao, X.; Liu, F.; Luo, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, L. Triterpenoids in jujube: A review of composition, content diversity, pharmacological effects, synthetic pathway, and variation during domestication. Plants 2023, 12, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Acker, S.A.; Tromp, M.N.; Griffioen, D.H.; Van Bennekom, W.P.; Van Der Vijgh, W.J.; Bast, A. Structural aspects of antioxidant activity of flavonoids. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burda, S.; Oleszek, W. Antioxidant and antiradical activities of flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2774–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musialik, M.; Kuzmicz, R.; Pawłowski, T.S.; Litwinienko, G. Acidity of hydroxyl groups: An overlooked influence on antiradical properties of flavonoids. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2699–2709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkiran, O.; Sabudak, T.; Ozturk, M.; Topcu, G. Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of flavonoids from Trifolium nigrescens Subsp. petrisavi. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 12598–12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, S.; Rayhan, N.M.A.; Emon, S.H.; Islam, T.; Rathry, K.; Hasan, M.; Mansur, M.I.; Srijon, B.C.; Islam, S.; Ray, A.; et al. Antioxidant activity of Schiff base ligands using the DPPH scavenging assay: An updated review. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 33094–33123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omrani, R.; Ali, R.B.; Selmi, W.; Arfaoui, Y.; El May, M.V.; Akacha, A.B. Synthesis, design, DFT Modeling, Hirshfeld Surface Analysis, crystal structure, anti-oxidant capacity and anti-nociceptive activity of dimethylphenylcarbamothioylphosphonate. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1217, 128429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Dehkordi, M.M.; Asgarshamsi, M.H. Density functional theory studies of the antioxidants a review. J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Yang, Z.; Rajca, A. From stable radicals to thermally robust high-spin diradicals and triradicals. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 11954–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, M. Current trends in computational quantum chemistry studies on antioxidant radical scavenging activity. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 2639–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanić, V.; Trošelj, K.G.; Lučić, B.; Marković, Z.; Amić, D. Bond dissociation free energy as a general parameter for flavonoid radical scavenging activity. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, H.J.; Choi, C.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, S.J.; Hahm, K.S.; Jeong, H.G. Ursolic acid enhances nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-α production via nuclear factor-κB activation in the resting macrophages. FEBS Lett. 2001, 509, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, N.Q.; Tat, C.T.; Thien, D.D.; Manh, H.D.; Yen, H.H.; Duc, N.A. Ursolic Acid from Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. Regulates Zymosan-Induced Inflammatory Signaling in Raw 264.7. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2024, 19, 148153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; An, J.; Shin, S.-A.; Moon, S.Y.; Kim, M.; Choi, S.; Kim, H.; Phi, K.-H.; Lee, J.H.; Youn, U.J.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of TP1 in LPS-induced Raw264. 7 macrophages. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2024, 67, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Yang, E.J.; Ku, S.K.; Song, K.S.; Bae, J.S. Anti-inflammatory effects of oleanolic acid on LPS-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Inflammation 2013, 36, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliyan, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Priyadarshini, A.; Vibhuti, A.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, R.P.; Chang, C.M. Determination of antioxidants by DPPH radical scavenging activity and quantitative phytochemical analysis of Ficus religiosa. Molecules 2022, 27, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papastergiadis, A.; Mubiru, E.; Van Langenhove, H.; De Meulenaer, B. Malondialdehyde measurement in oxidized foods: Evaluation of the spectrophotometric thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test in various foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9589–9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.S.; Sedeek, M.S.; Farag, M.A.; Abdelnaser, A. Terfezia boudieri and Terfezia claveryi inhibit the LPS/IFN-γ-mediated inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages through an Nrf2-independent mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyaprom, S.; Srisai, P.; Intachaisri, V.; Kaewkod, T.; Pekkoh, J.; Desvaux, M.; Tragoolpua, Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity on LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophage cells of white mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaf extracts. Molecules 2023, 28, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florescu, D.N.; Boldeanu, M.-V.; Șerban, R.-E.; Florescu, L.M.; Serbanescu, M.-S.; Ionescu, M.; Streba, L.; Constantin, C.; Vere, C.C. Correlation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, inflammatory markers, and tumor markers with the diagnosis and prognosis of colorectal cancer. Life 2023, 13, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charrad, R.; Berraïes, A.; Hamdi, B.; Ammar, J.; Hamzaoui, K.; Hamzaoui, A. Anti-inflammatory activity of IL-37 in asthmatic children: Correlation with inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-β, IL-6 and IL-17A. Immunobiology 2016, 221, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | BDE | IP | PA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Water | DMSO | Gas | Water | DMSO | Gas | Water | DMSO | |

| 1-C12-H | 105.0 | 104.1 | 104.4 | 170.2 | 111.6 | 116.9 | 362.5 | 106.1 | 86.3 |

| 1-3-OH | 98.0 | 97.8 | 97.8 | 366.3 | 70.0 | 49.8 | |||

| 3-C12-H | 104.7 | 104.0 | 103.9 | 169.1 | 112.5 | 118.1 | 401.5 | 108.4 | 88.5 |

| 3-2-OH | 96.5 | 97.1 | 96.9 | 363.6 | 68.2 | 48.3 | |||

| 3-3-OH | 96.5 | 96.6 | 96.3 | 360.0 | 67.4 | 47.2 | |||

| Compounds | PDB ID | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen Bond | Hydrophobic Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 5KIR | −6.265 | - | His351 |

| 3W5E | −6.146 | Gln284, Asn283, Tyr233, Asp392 | His278, His234, Phe414, Phe446 | |

| 7 | 5KIR | −6.957 | Tyr355, Gln192 | His351, Lys358 |

| 3W5E | −9.63 | His234, Val281, Glu509 | Phe446, Tyr233, Phe506 | |

| 8 | 5KIR | −7.17 | Tyr355, Gly354, Asn350, His356, Asp347 | Lys358, His351 |

| 3W5E | −9.74 | Glu304, Tyr233 | Phe446, Ser282 | |

| rofecoxib | 5KIR | −8.9 | Arg513 | Leu352, Val349, Val523, Ser353, Ala527, His90 |

| NVW | 3W5E | −12.05 | Gln443 | Ile410, Met503, Leu502, Phe414, Met347 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hung, N.A.; Le, V.T.T.; Hung, N.V.; Tam, H.T.M.; Linh, N.N.; Hop, N.Q.; Hanh, N.T.; Lam, D.T. In Silico and In Vitro Insights into the Pharmacological Potential of Pouzolzia zeylanica. Molecules 2026, 31, 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020357

Hung NA, Le VTT, Hung NV, Tam HTM, Linh NN, Hop NQ, Hanh NT, Lam DT. In Silico and In Vitro Insights into the Pharmacological Potential of Pouzolzia zeylanica. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020357

Chicago/Turabian StyleHung, Nguyen Anh, Vu Thi Thu Le, Nguyen Viet Hung, Ha Thi Minh Tam, Nguyen Ngoc Linh, Nguyen Quang Hop, Nguyen Thi Hanh, and Do Tien Lam. 2026. "In Silico and In Vitro Insights into the Pharmacological Potential of Pouzolzia zeylanica" Molecules 31, no. 2: 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020357

APA StyleHung, N. A., Le, V. T. T., Hung, N. V., Tam, H. T. M., Linh, N. N., Hop, N. Q., Hanh, N. T., & Lam, D. T. (2026). In Silico and In Vitro Insights into the Pharmacological Potential of Pouzolzia zeylanica. Molecules, 31(2), 357. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020357