Various Analytical Techniques Reveal the Presence of Damaged Organic Remains in a Neolithic Adhesive Collected During Archeological Excavations in Cantagrilli (Florence Area, Italy)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

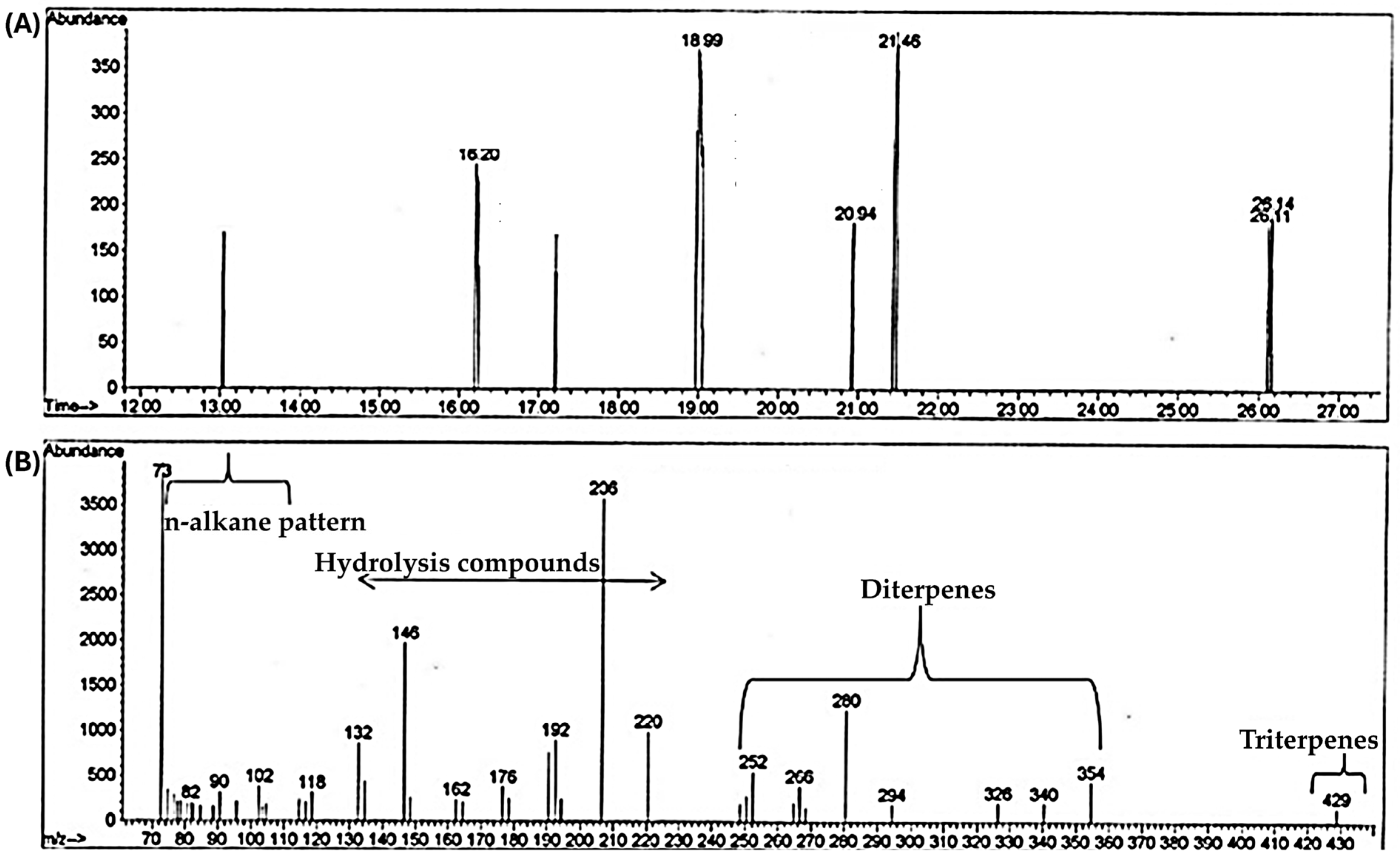

2.1. GC-MS Experimental Results

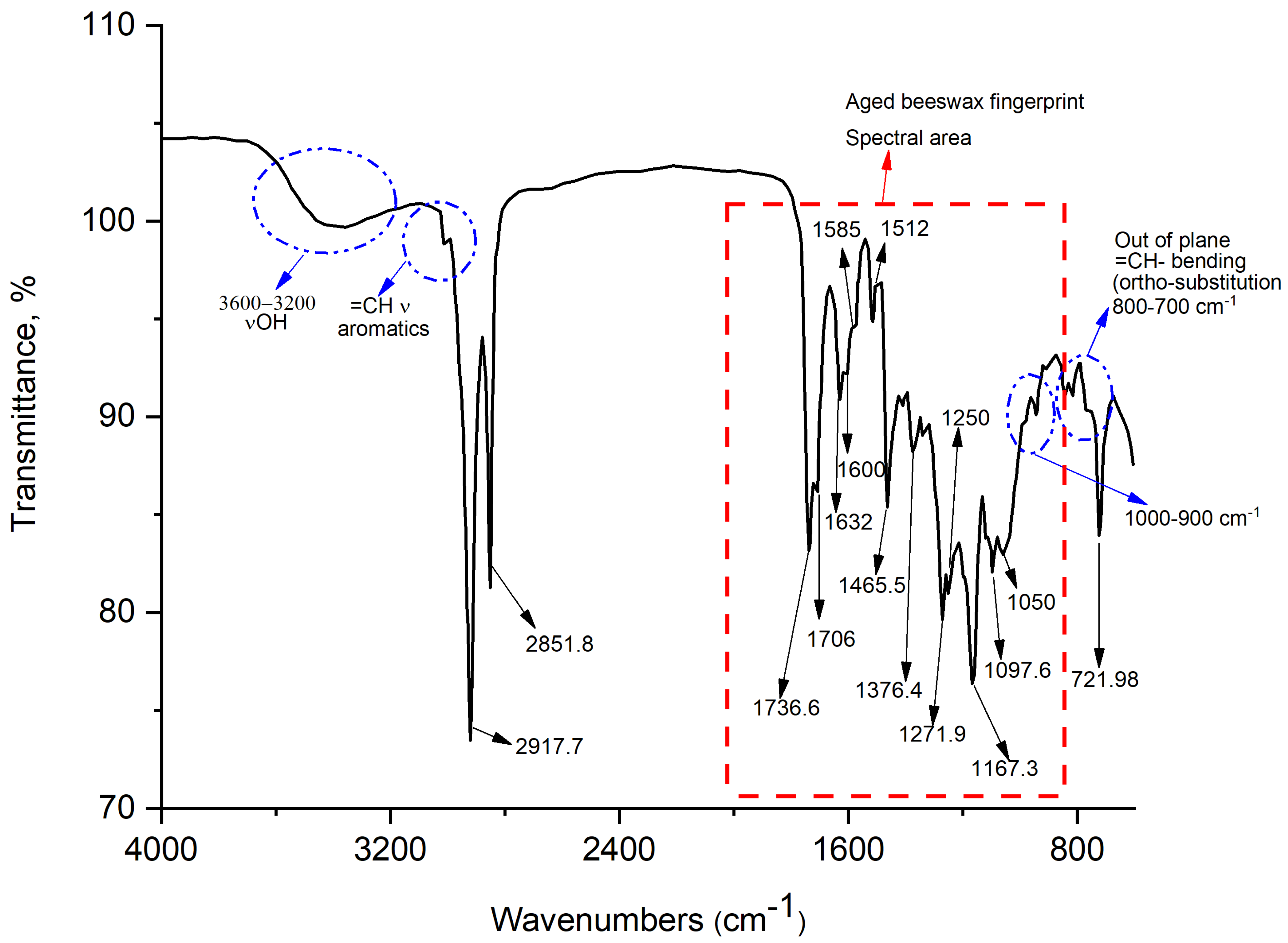

2.2. FTIR Results

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Vibration Mode | Functional Groups | References | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3200–3500 | Stretching vibrations | OH hydrogen bonded | [20] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 3000–3100 | Stretching vibrations | =C-H | [20] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 2917–2920 | Stretching vibrations (νas) | -CH2- | [23] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 2848–2851 | Stretching vibrations (νs) | -CH3 | [20] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 1694–1703 | (νas out-of-plane) | -C(=O) in esters group | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 1700 | (νs) anhydride | C(=O)-O-C(=O) | [25] | Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 1703 | (νas) anhydride | C(=O)-O-C(=O) | [25] | Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 1632 | Asymmetric stretching vibrations (νas) | C(=O) hydrogen bonded | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] Vanillin [24] |

| 1585–1600 | ν in aromatic ring | -C=C- | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 1400–1500 | ν in aromatic ring | -C=C- | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 1465 | δscissoring hydrocarbon chain | CH3-(CH2)n-CH3 | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 1376–1327 | δ (CH3) ν/δ C(=O)-OH | Methyl (CH3) bending stretching/bending combination | [26] | Phenolic resins [21,22] Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 1000–1250 | In-plane bending δ | -CH- | [20] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 1167 | ν | C(=O)O- esters | [20] | Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 1150 | δ ether groups in pure vanillin | -CH- in ester chain | [25] | Phenolic resins [21,22] Vanillin [24] |

| 1050 | ν ethers in esters and anhydride groups | C(=O)-O- C(=O)-O-C(=O) | [25] | Aged beeswax [23,24] |

| 800–900 | Para substitution in the aromatic ring |  1,4 1,4 | [20,21] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 700–800 | Orto substitution in the aromatic ring |  1,2 1,2 | [20,21] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

| 721.98 | δ long aliphatic chains | CH3-(CH2)n-CH3 | [20,21] | Phenolic resins [21,22] |

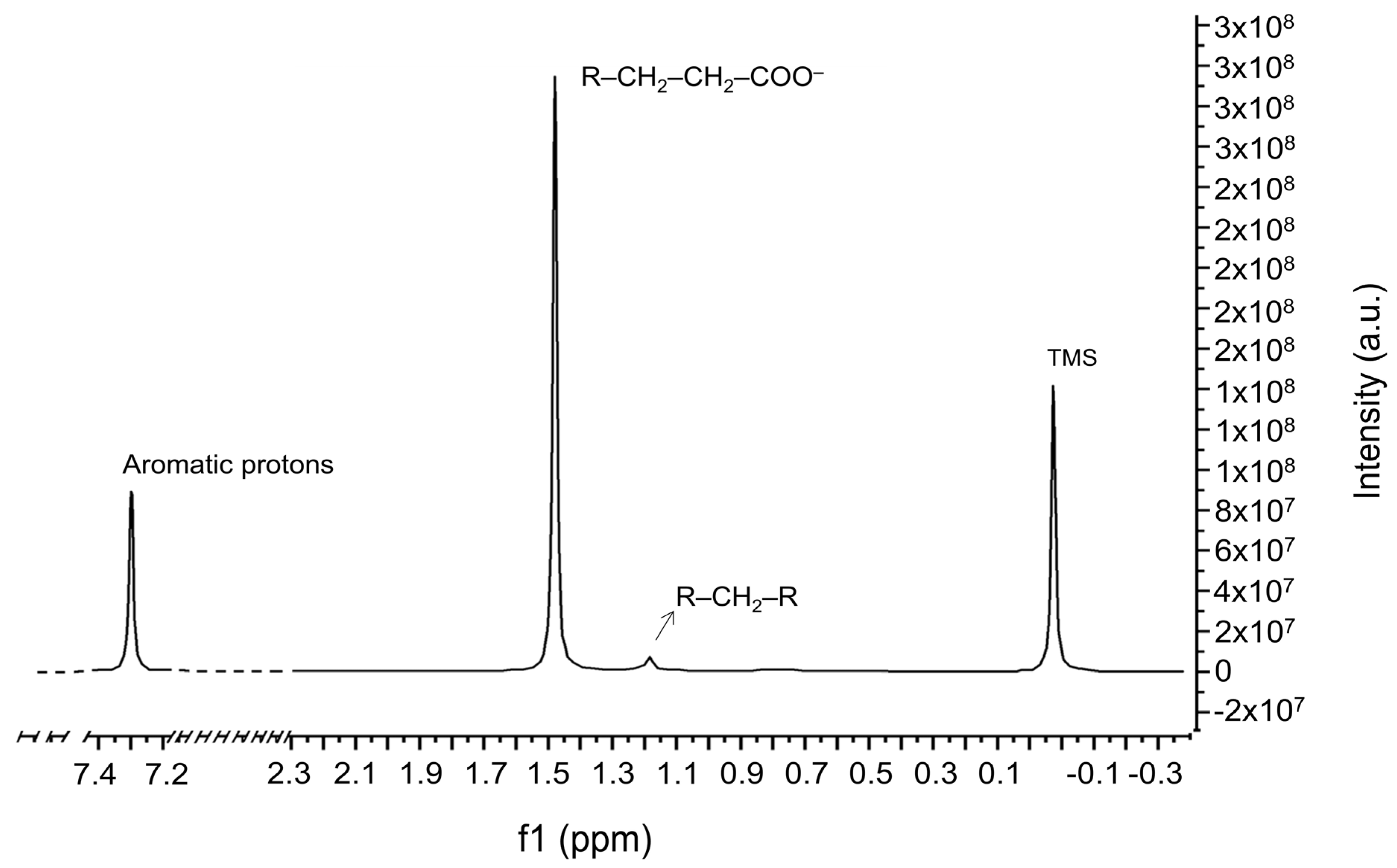

2.3. NMR Results

| 1H-NMR Spectral Data and Chemical Shift Assignments | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Functional Groups | Description | 1H-NMR (ppm) | References |

| R-CH2-R | Methylene group | 1.29 | [24] |

| R-CH2-CH2-COO− | Ester-carboxylic acid | 1.62 | [24] |

| Protons of flavones | Aromatic protons of flavones AA’BB’ systems | 7.30 | [22,30] |

| 13C-NMR Spectral Data and Chemical Shift Assignments | |||

| Chemical Functional Groups | Description | 13C-NMR (ppm) | References |

| α-CH3 | α-Carbon of chain alkanes | 14–16 | [28,29] |

| β-CH2 | β-Carbon of chain alkanes | 24–26 | [28,29] |

| γ-CH2; δ-CH2; ε-CH2 | γ, δ, and ε-Carbon of chain alkanes | 23–38 | [28,29] |

| C-OH; C-O | Oxygenated species (ethers; alcohols) | 53 | [28,29] |

| C(=O)O- | Oxygenated species (mainly esters) | 174.26 | [24] |

| (-C=C-; Csp2) | The unsaturation in methyl esters | 131.88 and 127.08 | [31] |

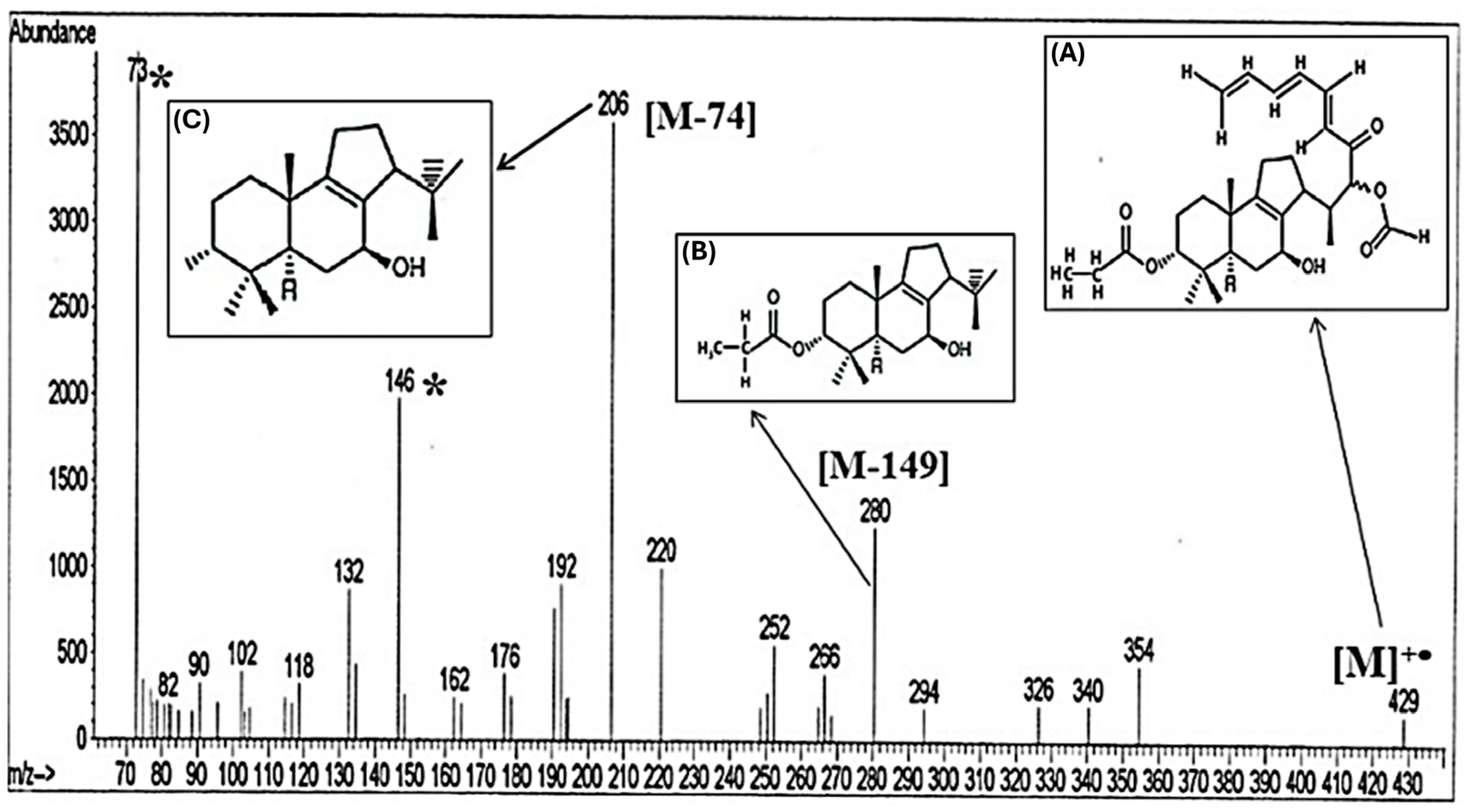

3. Discussion

| Name |

NIST

Formula |

NIST

Observed Mol. Mass |

NIST

Theo. Mol. Mass. |

Rt

(min) |

Peak Rating

(Max.) | Notes and Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trimethylsilyl radical | C3H9Si | 73.18 * | 73.19 | 17.19 | 10 | A typical silyl derivative radical involved in the molecular fragmentation mechanism of fats, included into archeological adhesives, prehistoric resins, and waxes [40,41] |

| 3-(Trimethylsilyl) propionic acid | C6H14O2Si | 146.25 * | 146.26 | 18.99 | 10 | A typical silyl derivative radical involved in the molecular fragmentation mechanism of fats, included into archeological adhesives, prehistoric resins, and waxes [40,41] |

| 3-Methyl-4-(2,6,6-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-1-yl)-3-buten-2-one | C14H22O | 206.31 | 206.32 | 20.94 | 10 | Sesquiterpenoids contained in the resins of T. mucronatum [42] |

| 12(S)-Hydroxy-(5Z,8E,10E)-heptadecatrienoic acid | C17H28O3 | 280.38 | 280.40 | 21.46 | 9.8 | Calocedrus formosana Florin (sesquiterpene family); essential oils and extractives of coniferous tree, classified in the family of Cupressaceae [43] |

| 4-[[(8R,9R,10R,11R,13S,14R,17R)-17-acetyl-10,13-dimethyl-3-oxo-1,2,6,7,8,9,11,12,14,15,16,17-dodecahydrocyclopenta[a]phenanthren-11-yl]oxy]-4-oxobutanoate | C25H33O6 | 429.23 | 429.50 | 26.14 | 9.5 | Stachybotrys (plants, microscopic fungus) thrives on damaged cellulose-rich plant-based materials; it represents the secondary metabolites of Stachybotrys [44] |

4. Materials and Methods

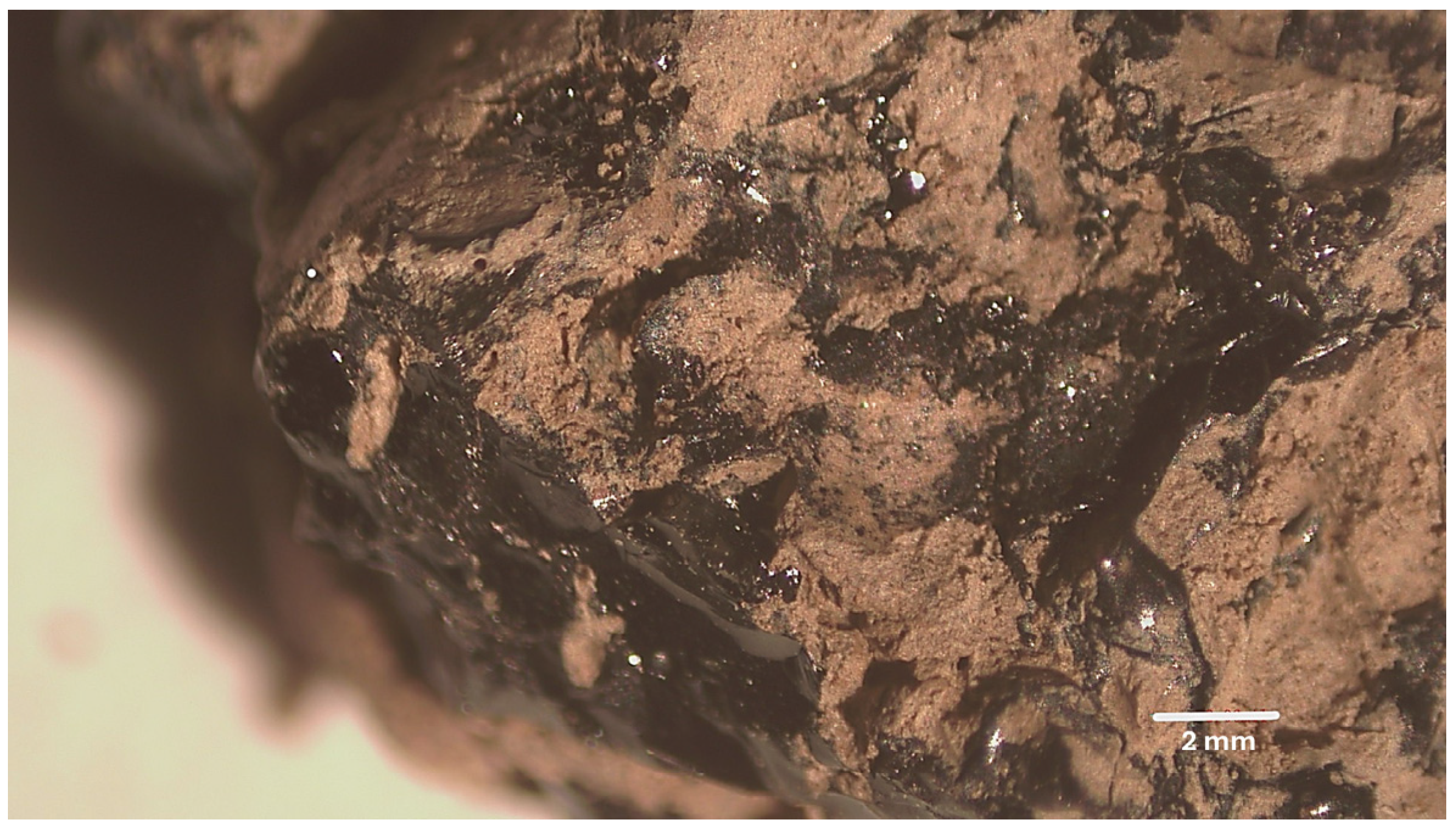

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Materials and Reagents

4.3. Procedures and Apparatuses

4.3.1. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

4.3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

4.3.3. 1H-Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry (1H-NMR)

4.3.4. 13C-Carbon Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry (13C-NMR)

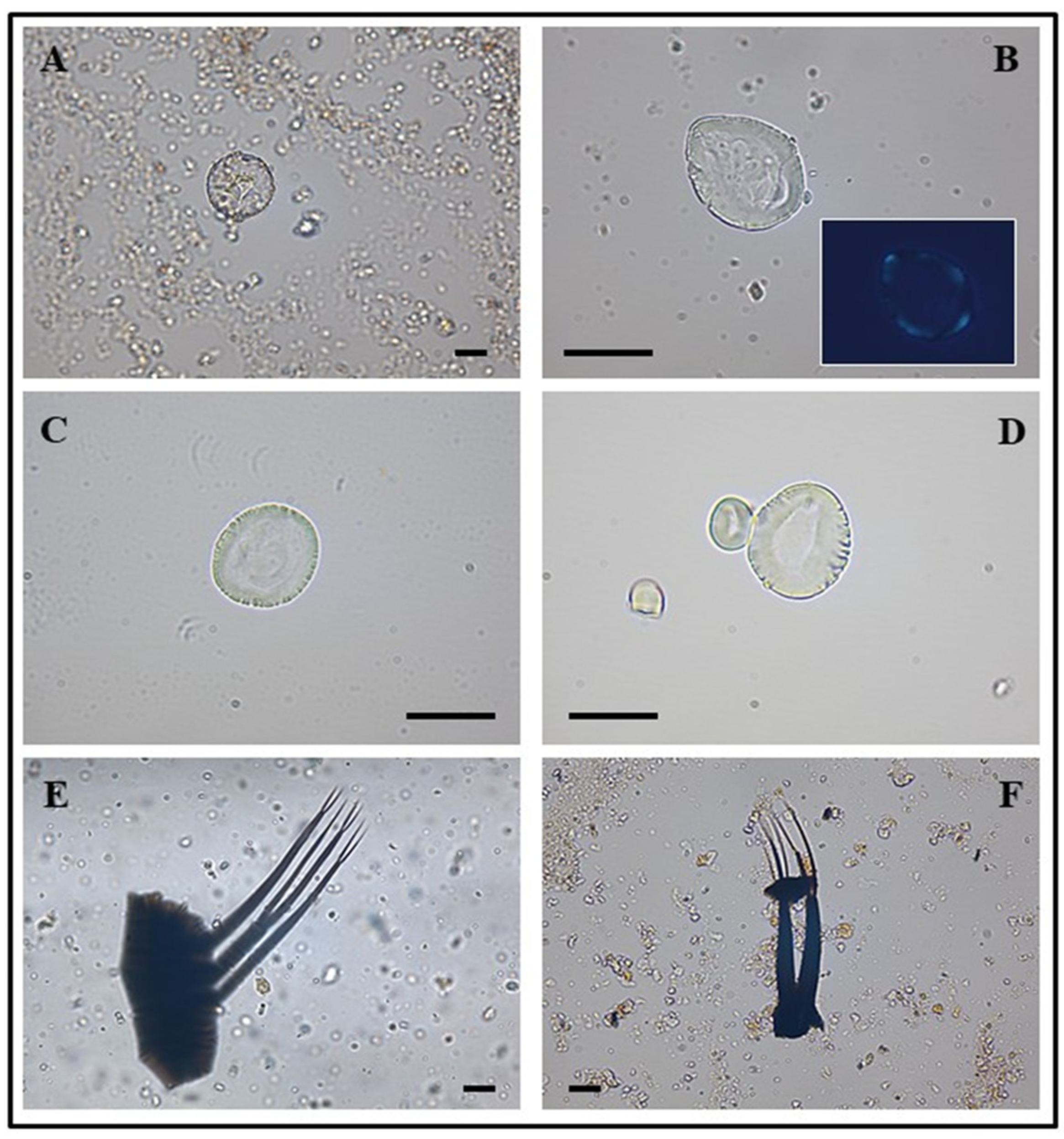

4.3.5. Archeobotanical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bisulca, C.; Pool, M.; Odegaard, N. A survey of plant and insect exudates in the archaeology of Arizona. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017, 15, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, P.P.A.; Martini, F.; Sala, B.; Magi, M.; Colombini, M.P.; Giachi, G.; Landucci, F.; Lemorini, C.; Modugno, F.; Ribechini, E. A new Palaeolithic discovery: Tar-hafted stone tools in a European mid-Pleistocene bone-bearing bed. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2006, 33, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtzis, N.; Moniaros, X. Mastic production in medieval Chios: Economic flows and transitions in an insular setting. J. Mediev. Mediterr. 2019, 31, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binford, L.R. Butchering, sharing, and the archaeological record. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 1984, 3, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langejans, G.; Aleo, A.; Fajardo, S.; Kozowyk, P. Archaeological adhesives. Ox. Res. Encycl. Anthropol. 2022, 117, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, N. (Ed.) Symposium on New Discoveries from the Excavation at Alawala; Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, University of Kelaniya: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Colombini, M.P.; Modugno, F. Organic Mass Spectrometry in Art and Archaeology; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, R.J.; Heron, C.; Sutton, M.Q. The chemistry, archaeology, and ethnography of a Native American insect resin. J. Calif. Great Basin Anthropol. 1998, 20, 53–71. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3gv304z9 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Seyfullah, L.J.; Beimforde, C.; Dal Corso, J.; Perrichot, V.; Rikkinen, J.; Schmidt, A.R. Production and preservation of resins—Past and present. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1684–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, R.J.; Cartwright, C.R.; McEwan, C. Chemical characterization of ancient Mesoamerican “copal” resins: Preliminary results. Archaeometry 2006, 48, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.R.; Langenheim, J.H. Plant resins: Chemistry, evolution, ecology and ethnobotany. Ann. Bot. 2004, 93, 784–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, P.; Charrié-Duhaut, A.; Connan, J.; Flecker, M.; Albrecht, P. Archaeological resinous samples from Asian wrecks: Taxonomic characterization by GC–MS. Anal. Chim. Acta 2009, 648, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.; Pollarolo, L.; Degano, I.; Birolo, L.; Pasero, M.; Biagioni, C. A milk and ochre paint mixture used 49,000 years ago in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0131273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardella, F.; Landi, N.; Degano, I.; Colombo, M.; Serradimigni, M.; Tozzi, C.; Ribechini, E. Chemical investigations of bitumen from Neolithic archaeological excavations in Italy by GC–MS combined with principal component analysis. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 1449–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, S.; Charmaine, K.; Colonese, A.C.; Lucquin, A.J.A. Pine traces at Star Carr: Evidence from residues on stone tools. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2018, 19, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rageot, M.; Pêche-Quilichini, K.; Py, V.; Filippi, J.J.; Fernandez, X.; Regert, M. Exploitation of beehive products, plant exudates and tars in Corsica during the Early Iron Age. Archaeometry 2016, 58, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Ramos, P.; Norlan, M.R.P.; Ignacio, A.F.C.; Gil, J.M. Potential of ATR–FTIR spectroscopy for the classification of natural resins. BEMS Rep. 2018, 4, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, J. Investigating Shellac: Documenting the Process, Defining the Product. A Study on the Processing Methods of Shellac, and the Analysis of Selected Physical and Chemical Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, The Institute of Archaeology, Conservation and History, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2012. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30827448.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Sarti, L.; Baglioni, L.; Matera, I.; Mustone, G.; Pallecchi, P.; Valentini, F.; Martini, F. Cantagrilli: Tradizione mesolitica e primo Neolitico in area fiorentina. Rass. Archeol. 2023, 30, 79–124. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds, 7th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jonmurodov, A.; Bobokalonov, J.; Usmanova, S.; Muhidinov, Z.; Liu, L. Value added products from plant processing. Agric. Sci. 2017, 8, 857–867. Available online: http://www.scirp.org/journal/as (accessed on 19 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tomou, E.M.; Chatziathanasiadou, M.V.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Tzakos, A.G.; Skaltsa, H. NMR-based chemical profiling, isolation and evaluation of the cytotoxic potential of the diterpenoid siderol from cultivated Sideritis euboea Heldr. Molecules 2020, 25, 2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miłek, M.; Drogoń, A.; Pyda, M.; Czerniecka-Kubicka, A.; Tomczyk, M.; Dżugan, M. The use of infrared spectroscopy and thermal analysis for the quick detection of adulterated beeswax. J. Apic. Res. 2020, 59, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoia, L.; Tolppa, E.L.; Pirovano, L.; Salanti, A.; Orland, M. 1H NMR and 31P NMR characterization of the lipid fraction in archaeological ointments. Archaeometry 2012, 54, 1076–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavia, D.; Lampman, G.; Kriz, G.; Vyvyan, J. Introduction to Spectroscopy, 5th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-495-11478-9. [Google Scholar]

- Fonta, J.; Salvadó, N.; Butí, S.; Enrich, J. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy as a suitable technique in the study of the materials used in waterproofing of archaeological amphorae. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 598, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardana, A.P.; Hidayati, N.; Shimizu, K. Ellagic acid derivative and its antioxidant activity of chloroform extract of stem bark of Syzygium polycephalum Miq. (Myrtaceae). Indones. J. Chem. 2018, 18, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cookson, D.J.; Smith, B.E. Determination of structural characteristics of saturates from diesel and kerosene fuels by carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1985, 57, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, R.J.; Rourke, J.P.; Wong, A.; Barrow, N.S.; Ellis, P.R.; Bishop, P.T.; Smith, M.E. 1H and 13C solution- and solid-state NMR investigation into wax products from the Fischer–Tropsch process. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2011, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kameya, T.; Takano, S.; Yanase, Y.; Jyunrin, C.; Iida, H.; Kanō, S.; Sakurai, K. Bisbenzylisoquinoline alkaloids and related compounds. VI. A modified total synthesis of the stereoisomeric mixture of dauricine. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1966, 14, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Khalid, N.; Khan, M.A. Identification, FT-IR, NMR (1H and 13C) and GC-MS studies of fatty acid methyl esters in biodiesel from rocket seed oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regert, M. Investigating the history of prehistoric glues by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Sep. Sci. 2004, 27, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aveling, E.M.; Heron, C. Identification of birch bark tar at the Mesolithic site of Star Carr. Anc. Biomol. 1998, 2, 69–80. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247936420_Identification_of_Birch_Bark_Tar_at_the_Mesolithic_Site_of_Star_Carr (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Irto, A.; Micalizzi, G.; Bretti, C.; Chiaia, V.; Mondello, L.; Cardiano, P. Lipids in archaeological pottery: A review on their sampling and extraction techniques. Molecules 2022, 27, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaduce, I.; Ribechini, E.; Modugno, F.; Colombini, M.P. Analytical approaches based on gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to study organic materials in artworks and archaeological objects. In Analytical Chemistry for Cultural Heritage; Mazzeo, R., Ed.; Topics in Current Chemistry Collections; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 291–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regert, M.; Rolando, C. Identification of archaeological adhesives using direct inlet electron ionization mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, K.B.; Nikolaeva, N.N.; Michria, M.V.; Revelsky, A.I. Investigation of Fragments of Lacquer Pieces from Archaeological Sites of the Orgoyton Burial Ground (Transbaikalia) Using Pyrolytic Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 77, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachur, H.J. Pharaonic Pyrolysis—Activity in the Libyan Desert: Interpretation of a Dyadic Ceramic. In Proceedings Pachur 2017; Freie Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halket, J.M.; Zaikin, V.G. Derivatization in mass spectrometry—3. Alkylation (arylation). Eur. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, L.d.C.; Pires, E.; Domoney, K.; Zuchtriegel, G.; McCullagh, J.S.O. A symbol of immortality: Evidence of honey in bronze jars found in a Paestum shrine dating to 530–510 BCE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 29756–29766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, A.; Needham, A.; Langley, A.; Elliott, B. Material and sensory experiences of Mesolithic resinous substances. Camb. Archaeol. J. 2023, 33, 217–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoneit, B.R.T.; Otto, A.; Oros, D.R.; Kusumoto, S. Terpenoids of the swamp cypress subfamily (Taxodioideae), Cupressaceae, an overview by GC–MS. Molecules 2019, 24, 3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Ko, H.-H.; Chen, J.-J.; Chang, H.-S.; Tseng, M.-H.; Wang, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. New furanone and sesquiterpene from the pericarp of Calocedrus formosana. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 845–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qian, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G. Filamentous fungi-derived orsellinic acid–sesquiterpene meroterpenoids: Fungal sources, chemical structures, bioactivities, and biosynthesis. Planta Med. 2023, 89, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.J.; Horning, M.G.; Vouros, P. Vapor phase bimolecular reactions of alkyl siliconium and other metal ions in mass spectrometry. Org. Mass Spectrom. 1971, 5, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, R.P.; Buchheim, M.A.; Portman, R.; Levetin, E. Molecular and ultrastructural detection of plastids in Juniperus (Cupressaceae) pollen. Phytologia 2016, 98, 298–310. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308993613_Molecular_and_ultrastructural_detection_of_plastids_in_Juniperus_Cupressaceae_pollen (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bogolitsyn, K.G.; Zubov, I.N.; Gusakova, M.A.; Chukhchin, D.G.; Krasikova, A.A. Juniper wood structure under the microscope. Planta 2015, 241, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modugno, F.; Ribechini, E.; Colombini, M.P. Aromatic resin characterisation by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1134, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekarforoush, E.; Mendes, A.; Baj, V.; Beeren, S.; Chronakis, I. Electrospun phospholipid fibers as micro-encapsulation and antioxidant matrices. Molecules 2017, 22, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkov, M.V.; Brinkevich, S.D.; Samovich, S.N.; Skornyakov, I.V.; Tolstorozhev, G.B.; Shadyro, O.I. Infrared spectra and structure of molecular complexes of aromatic acids. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2012, 78, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, R. The impact of heat-moisture treatment on molecular structures and properties of starches isolated from different botanical sources. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 50, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Copeland, L. Molecular disassembly of starch granules during gelatinization and its effect on starch digestibility: A review. Food Funct. 2013, 4, 1564–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L.; Hardy, K. Archaeological starch. Agronomy 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gismondi, A.; D’Agostino, A.; Canuti, L.; Di Marco, G.; Basoli, F.; Canini, A. Starch granules: A data collection of 40 food species. Plant Biosyst. 2019, 153, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, A. The differential survival of native starch during cooking and implications for archaeological analyses: A review. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2012, 4, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, R. Description, classification, and identification. In Ancient Starch Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 115–143. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Sánchez, M.L.; Hegna, T.A.; Schaaf, P.; Pérez, L.; Centeno-García, E.; Vega, F.J. The aquatic and semiaquatic biota in Miocene amber from the Campo La Granja Mine (Chiapas, Mexico): Paleoenvironmental implications. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2015, 62, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schädel, M.; Hörnig, M.K.; Hyžný, M. Mass occurrence of small isopodan crustaceans in 100-million-year-old amber: An extraordinary view on behaviour of extinct organisms. Paläontol. Z. 2021, 95, 429–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huys, R.; Suárez-Morales, E.; Serrano-Sánchez, M. Early Miocene amber inclusions from Mexico reveal antiquity of mangrove-associated copepods. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, D.; De Gracia, C.; Carrillo-Briceño, J.D.; Aguirre-Fernández, G.; Jaramillo, C.; Benites-Palomino, A.; Atencio-Araúz, J.E. Shark–cetacean trophic interactions during the Late Pliocene in the central eastern Pacific (Panama). Palaeontol. Electron. 2019, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regert, M.; Delacotte, J.M.; Menu, M.; Petrequin, P.; Rolando, C. Identification of Neolithic adhesives from two lake dwellings at Chalain (Jura, France). Anc. Biomol. 1998, 2, 81–96. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/11553065/REGERT_M_DELACOTTE_J_M_MENU_M_PETREQUIN_P_et_ROLANDO_C_1998_Identification_of_neolithic_hafting_adhesives_from_two_lake_dwellings_at_Chalain_Jura_France_Ancient_Biomolecules_2_81_96 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). NIST Chemistry WebBook. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- ICSN. The International Code for Starch Nomenclature. Available online: http://fossilfarm.org/ICSN/Code.html (accessed on 15 September 2025).

| No. of Identified Compounds | Compound Description | Retention Time (min) | m/z Range * |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Triterpenes | ≥22 | 400–550 |

| 2 | Diterpenes | 14–20 | 252–354 |

| 3 | Hydrolysis products (Monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenes) | 3–13 | 132–220 |

| 4 | n-Alkane pattern (belonging to the long hydrophobic hydrocarbon chains—alkanes—of fatty acid esters) | 3–13 | 73–118 |

| Hypothesized and Detected Compounds | MW | Main Fragments m/z | Class C Atoms No. of Isoprene Units (n) | Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C25H33O6 (A) | 429 | [M]+• molecular peak | Sesterterpenoids 25 5 | Cupressaceae (e.g., Juniper sp. and Cupressus sp.) | [12] |

| C17H25 3HO3 (C17H28O3) (B) | 280 | [M−149] where the fragment that is lost (149) is  (C8H3 2HO3) (C8H3 2HO3) | Diterpenoids; sesquiterpenoids 17 3 | Fatty acids, usually vegetable oils contained in alkyd resins | [17] |

| C14H22O (C) | 206 | [M−74] basic peak where the fragment that is lost (74) is propionic acid  | Monoterpenoids 14 2 | Lower-molecular-weight fatty acids, C6 to C14 | [16] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Valentini, F.; Sarti, L.; Martini, F.; Pallecchi, P.; Allegrini, I.; Colasanti, I.A.; Zaratti, C.; Macchia, A.; Gismondi, A.; D’Agostino, A.; et al. Various Analytical Techniques Reveal the Presence of Damaged Organic Remains in a Neolithic Adhesive Collected During Archeological Excavations in Cantagrilli (Florence Area, Italy). Molecules 2026, 31, 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020274

Valentini F, Sarti L, Martini F, Pallecchi P, Allegrini I, Colasanti IA, Zaratti C, Macchia A, Gismondi A, D’Agostino A, et al. Various Analytical Techniques Reveal the Presence of Damaged Organic Remains in a Neolithic Adhesive Collected During Archeological Excavations in Cantagrilli (Florence Area, Italy). Molecules. 2026; 31(2):274. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020274

Chicago/Turabian StyleValentini, Federica, Lucia Sarti, Fabio Martini, Pasquino Pallecchi, Ivo Allegrini, Irene Angela Colasanti, Camilla Zaratti, Andrea Macchia, Angelo Gismondi, Alessia D’Agostino, and et al. 2026. "Various Analytical Techniques Reveal the Presence of Damaged Organic Remains in a Neolithic Adhesive Collected During Archeological Excavations in Cantagrilli (Florence Area, Italy)" Molecules 31, no. 2: 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020274

APA StyleValentini, F., Sarti, L., Martini, F., Pallecchi, P., Allegrini, I., Colasanti, I. A., Zaratti, C., Macchia, A., Gismondi, A., D’Agostino, A., Canini, A., & Neri, A. (2026). Various Analytical Techniques Reveal the Presence of Damaged Organic Remains in a Neolithic Adhesive Collected During Archeological Excavations in Cantagrilli (Florence Area, Italy). Molecules, 31(2), 274. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020274