Disrupted Vitamin D Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Free and Bioavailable 25(OH)D as Novel Biomarkers of Hepatic Reserve and Clinical Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

2.2. Vitamin D Status and Binding Proteins

2.3. Disease Aetiology and Clinical Staging

2.4. Correlation Analyses

- Model 1 (Unadjusted): Individual univariate logistic regression models for each predictor against HCC status. Age was entered as continuous (per 10-year increment) and sex as binary (male vs. female).

- Model 2 (Age & Sex Adjusted): All predictors adjusted for age (per 10-year increment) and male sex.

- Model 3 (Full Model): Adjusted for age, sex, albumin, and vitamin D fractions (free and bioavailable 25(OH)D). VDBP was excluded from the full model due to collinearity with albumin (Spearman ρ = 0.395, p = 0.007); albumin was retained as the primary carrier protein measure given its stronger association with clinical outcomes (Child–Pugh score).

- Free 25(OH)D (per 5 pmol/L increase): Reflects the unbound hormone fraction accessible to tissue receptors. In the full model, higher free 25(OH)D was significantly associated with HCC (aOR 1.34, 95% CI 1.08–1.67, p = 0.008), likely a mathematical consequence of severe albumin and VDBP depletion in HCC patients rather than true vitamin D sufficiency.

- Bioavailable 25(OH)D (per 5 nmol/L): Represents free plus albumin-bound 25(OH)D. In the full model, bioavailable 25(OH)D did not retain independent significance (aOR 0.91, 95% CI 0.64–1.29, p = 0.591) after adjustment for albumin, suggesting that the association observed in univariate analysis is largely explained by hypoalbuminaemia.

- AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): Model 2 AUC = 0.984 (95% CI 0.971–0.997); Model 3 AUC = 0.989 (95% CI 0.978–0.999), indicating excellent discrimination between HCC patients and controls. The marginal improvement from Model 2 to Model 3 suggests that vitamin D fractions contribute little independent predictive value beyond age, sex and albumin.

- Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit Test: Model 2, p = 0.837; Model 3, p = 0.925. Both p-values > 0.05, indicating excellent fit (model predictions align well with observed outcomes).

- Nagelkerke R2: Model 2, R2 = 0.792; Model 3, R2 = 0.825. These values indicate that Models 2 and 3 explain approximately 79–83% of the variance in HCC status, reflecting the strong and largely demographic/anthropometric nature of the discrimination between HCC patients and healthy controls.

3. Discussion

3.1. Principal Findings and Interpretation

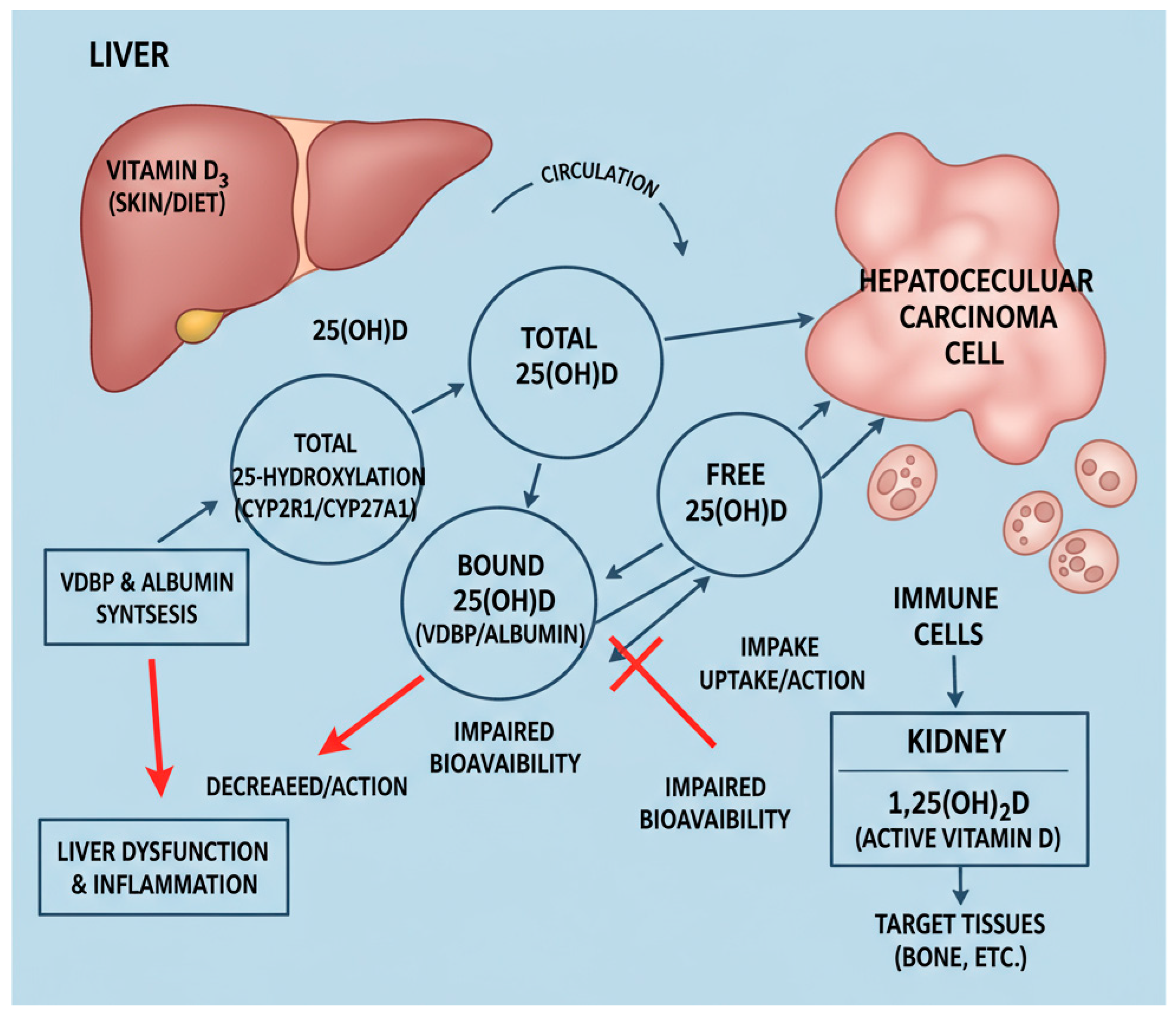

3.2. Mechanisms Underlying Vitamin D Perturbation in HCC

3.3. Multivariable Analysis Results

3.4. Comparison with Prior Studies

3.5. Clinical Implications and Limitations of Current Vitamin D Assessment

3.6. Study Strengths

3.7. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population and Design

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.3. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

4.4. Clinical Data Collection

4.5. Biochemical Measurements

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 25(OH)D | 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

| BCLC | Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer |

| HBV | hepatitis B virus |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | hepatitis C virus |

| PBC | primary biliary cholangitis |

| VDBP | vitamin D-binding protein |

| VDR | vitamin D receptor |

References

- Feldman, D.; Krishnan, A.V.; Swami, S.; Giovannucci, E.; Feldman, B.J. The role of vitamin D in reducing cancer risk and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeb, K.K.; Trump, D.L.; Johnson, C.S. Vitamin D signalling pathways in cancer: Potential for anticancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 684–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D: Production, metabolism, and mechanisms of action. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Adler, R.A., Ahmed, S.F., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDText.com: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dallavalasa, S.; Tulimilli, S.V.; Bettada, V.G.; Karnik, M.; Uthaiah, C.A.; Anantharaju, P.G.; Nataraj, S.M.; Ramashetty, R.; Sukocheva, O.A.; Tse, E.; et al. Vitaminqw D in Cancer Prevention and Treatment: A Review of Epidemiological, Preclinical, and Cellular Studies. Cancers 2024, 16, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adelani, I.B.; Rotimi, O.A.; Maduagwu, E.N.; Rotimi, S.O. Vitamin D: Possible Therapeutic Roles in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 642653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markotić, A.; Kelava, T.; Markotić, H.; Silovski, H.; Mrzljak, A. Vitamin D in liver cancer: Novel insights and future perspectives. Croat. Med. J. 2022, 63, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.C.; Yen, C.L.; Yeh, C.N.; Hsu, J.T.; Chen, L.W.; Kuo, S.F.; Wang, S.Y.; Sun, C.C.; Kittaka, A.; Chen, T.C.; et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma cells express 25OHD-1-hydroxylase and are able to convert 25OHD to 1,25OH2D, leading to the 25OHD-induced growth inhibition. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 154, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépo, E.; Ouziel, R.; Pradat, P.; Momozawa, Y.; Quertinmont, E.; Gervy, C.; Gustot, T.; Degré, D.; Vercruysse, V.; Deltenre, P.; et al. Marked 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is associated with poor prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2013, 59, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Găman, M.A.; Kord-Varkaneh, H.; Rahmani, J.; Salehi-Sahlabadi, A.; Day, A.S.; Xu, Y. Serum Vitamin D Levels and Risk of Liver Cancer: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Nutr. Cancer 2021, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchetta, I.; Carotti, S.; Labbadia, G.; Gentilucci, U.V.; Muda, A.O.; Angelico, F.; Silecchia, G.; Leonetti, F.; Fraioli, A.; Picardi, A.; et al. Liver vitamin D receptor, CYP2R1, and CYP27A1 expression: Relationship with liver histology and vitamin D3 levels in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2012, 56, 2180–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.; Bouillon, R.; Thadhani, R.; Schoenmakers, I. Vitamin D metabolites in captivity? Should we measure free or total 25(OH)D to assess vitamin D status? J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 173, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.B.; Gallagher, J.C.; Jorde, R.; Berg, V.; Walsh, J.; Eastell, R.; Evans, A.L.; Bowles, S.; Naylor, K.E.; Jones, K.S.; et al. Determination of Free 25(OH)D Concentrations and Their Relationships to Total 25(OH)D in Multiple Clinical Populations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 3278–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero-Guerrero, R.; Mendez-Guerrero, O.; Carranza-Carrasco, A.; Tejeda, F.; Ardon-Lopez, A.; Navarro-Alvarez, N. Beyond bones: Revisiting the role of vitamin D in chronic liver disease. World J. Hepatol. 2025, 17, 112315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, T.L.; Sîrbe, C.; Benţa, G.; Mititelu, A.; Grama, A. The Role of Vitamin D and Vitamin D Binding Protein in Chronic Liver Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beringer, A.; Miossec, P. IL-17 and TNF-α co-operation contributes to the proinflammatory response of hepatic stellate cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 198, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.P.; Long, J.A.; Zhang, Y.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Li, Q.J.; Zhang, D.M.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, R.H.; Zhou, Z.G.; Xu, Y.J.; et al. Serum Bioavailable, Rather Than Total, 25-hydroxyvitamin D Levels Are Associated With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival. Hepatology 2020, 72, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelmeier, F.; Kronenberger, B.; Köberle, V.; Bojunga, J.; Zeuzem, S.; Trojan, J.; Piiper, A.; Waidmann, O. Severe 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency identifies a poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma—A prospective cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 39, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollid, S.T.; Hutchinson, M.Y.; Berg, V.; Fuskevåg, O.M.; Figenschau, Y.; Thorsby, P.M.; Jorde, R. Effects of vitamin D binding protein phenotypes and vitamin D supplementation on serum total 25(OH)D and directly measured free 25(OH)D. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 174, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D.; Schwartz, J. Vitamin D Binding Protein, Total and Free Vitamin D Levels in Different Physiological and Pathophysiological Conditions. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.T.; Wang, C.H.; Wang, J.D.; Chen, K.T.; Li, C.Y. Nonlinear associations of serum vitamin D levels with advanced liver disease and mortality: A US Cohort Study. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2025, 18, 17562848251338669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Wu, X.; Zhou, X.; Deng, R.; Ma, Y. Vitamin D receptor FOK I Polymorphism and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in HBV-Infected Patients. Hepat. Mon. 2019, 19, e85075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, C.E.; Evans, M.K.; Wenger, J.; Zonderman, A.B.; Berg, A.H.; Nalls, M.; Tamez, H.; Zhang, D.; Bhan, I.; Karumanchi, S.A.; et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefzadeh, P.; Shapses, S.A.; Wang, X. Vitamin D Binding Protein Impact on 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Levels under Different Physiologic and Pathologic Conditions. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 981581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikle, D. Nonclassical actions of vitamin D. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.C.; Bikle, D.D.; Lizaola, B.; Hayssen, H.; Terrault, N.A.; Schwartz, J.B. Total 25 (OH) vitamin D, free 25 (OH) vitamin D and markers of bone turnover in cirrhotics with and without synthetic dysfunction. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 2294–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Kuznia, S.; Boakye, D.; Schöttker, B.; Brenner, H. Vitamin D-Binding Protein, Bioavailable, and Free 25(OH)D, and Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaksch, M.; Jorde, R.; Grimnes, G.; Joakimsen, R.; Schirmer, H.; Wilsgaard, T.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Njølstad, I.; Løchen, M.L.; März, W.; et al. Vitamin D and mortality: Individual participant data meta-analysis of standardized 25-hydroxyvitamin D in 26916 individuals from a European consortium. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgen, A.; Kani, H.T.; Akdeniz, E.; Alahdab, Y.O.; Ozdogan, O.; Gunduz, F. Effects of vitamin D level on survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol. Forum 2020, 1, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A.; Verdonck, L.; Kaufman, J.M. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 84, 3666–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D in health and disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sort, P.; Navasa, M.; Arroyo, V.; Aldeguer, X.; Planas, R.; Ruiz-del-Arbol, L.; Castells, L.; Vargas, V.; Soriano, G.; Guevara, M.; et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginès, P.; Cárdenas, A.; Arroyo, V.; Rodés, J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, C.; Tselekouni, P.; Kalafateli, M.; Triantos, C. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with liver cirrhosis. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2016, 29, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeley, M.P.; Andolino, C.; Kiesel, V.A.; Teegarden, D. Vitamin D regulation of energy metabolism in cancer. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 179, 2890–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männistö, V.; Jääskeläinen, T.; Färkkilä, M.; Jula, A.; Männistö, S.; Lundqvist, A.; Zeller, T.; Blankenberg, S.; Salomaa, V.; Perola, M.; et al. Low serum vitamin D level associated with incident advanced liver disease in the general population—A prospective study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Zorzi, J.; Ho, W.J.; Baretti, M.; Azad, N.S.; Griffith, P.; Dao, D.; Kim, A.; Philosophe, B.; Georgiades, C.; et al. Relationship of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage and Hepatic Function to Health-Related Quality of Life: A Single Center Analysis. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/liver-cancer/stages/bclc-staging-system-child-pugh-system (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. In Hepatocellular Carcinoma; Version 2.2024; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1514 (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiaSorin. LIAISON® 25 OH Vitamin D TOTAL Assay; DiaSorin SpA: Saluggia, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- R&D Systems. Human VDBP/GC-Globulin Quantikine ELISA Kit; R&D Systems, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Siuka, D.; Rakusa, M.; Vodenik, A.; Vodnik, L.; Štabuc, B.; Štubljar, D.; Drobne, D.; Jerin, A.; Matelič, H.; Osredkar, J. Free and Bioavailable Vitamin D Are Correlated with Disease Severity in Acute Pancreatitis: A Single-Center, Prospective Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Controls Winter (n = 87) | Controls Summer (n = 87) | p-Value (W vs. S) * | HCC (n = 46) | p-Value (HCC vs. C Winter) * | p-Value (HCC vs. C Summer) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M/F) | 14/73 | 14/73 | 1.000 | 39/7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 35.9 ± 12.5 | 35.9 ± 12.5 | 1.000 | 71.4 ± 7.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VDBP (mg/L) | 239.9 ± 141.9 | 236.9 ± 164.4 | 0.549 | 177.3 ± 237.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 48.0 ± 3.9 | 49.4 ± 4.2 | 0.028 | 35.9 ± 5.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Total 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 44.1 ± 17.8 | 75.0 ± 22.8 | <0.001 | 39.3 ± 22.1 | 0.061 | <0.001 |

| Free 25(OH)D (pmol/L) | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 1.9 | <0.001 | 27.3 ± 22.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Bioavailable 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 7.4 ± 5.7 | 13.1 ± 8.3 | <0.001 | 8.5 ± 6.3 | 0.183 | <0.001 |

| Etiology | n | M/F | BCLC 0 | BCLC 1 | BCLC 2 | BCLC 3 | BCLC 4 | p-Value (Overall) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcoholic | 28 | 25/3 | 2 | 6 | 15 | 4 | 1 | 0.012 |

| HBV | 3 | 1/2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| HCV | 5 | 4/1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Hemochromatosis | 1 | 1/0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Metabolic | 6 | 6/0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cryptogenic | 2 | 2/0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| PBC | 1 | 0/1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Variables | ρ | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| VDBP vs. Albumin | 0.395 | 0.007 |

| VDBP vs. Total 25(OH)D | 0.347 | 0.018 |

| VDBP vs. Free 25(OH)D | −0.606 | <0.001 |

| VDBP vs. Bioavailable 25(OH)D | −0.541 | <0.001 |

| Albumin vs. Free 25(OH)D | −0.327 | 0.026 |

| Albumin vs. Child–Pugh Score | −0.565 | <0.001 |

| Total 25(OH)D vs. Free 25(OH)D | 0.463 | 0.002 |

| Total 25(OH)D vs. Bioavailable 25(OH)D | 0.476 | 0.001 |

| Free 25(OH)D vs. Bioavailable 25(OH)D | 0.971 | <0.001 |

| Child–Pugh Score vs. BCLC Stage | 0.378 | 0.012 |

| Variable | Model 1: Unadjusted | Model 2: Age & Sex Adjusted | Model 3: Full Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI), p | aOR (95% CI), p | aOR (95% CI), p | |

| Age (per 10 years) | 8.42 (4.21–16.85), <0.001 | 7.12 (3.18–15.92), <0.001 | 6.89 (2.94–16.14), <0.001 |

| Male sex | 71.24 (18.45–275.0), <0.001 | 45.67 (9.82–212.4), <0.001 | 38.42 (7.65–193.0), <0.001 |

| 25(OH)D3 (per 10 nmol/L ↓) | 1.09 (0.94–1.26), 0.258 | 1.08 (0.89–1.31), 0.422 | 1.12 (0.86–1.46), 0.391 |

| Free 25(OH)D (per 5 pmol/L ↑) | - | - | 1.34 (1.08–1.67), 0.008 |

| Bioavail 25(OH)D (per 5 nmol/L) | - | - | 0.91 (0.64–1.29), 0.591 |

| Albumin (per 5 g/L ↓) | 3.89 (2.54–5.96), <0.001 | 2.84 (1.76–4.58), <0.001 | 2.41 (1.42–4.09), 0.001 |

| VDBP (per 100 mg/L ↓) | 1.24 (0.89–1.73), 0.205 | 0.97 (0.68–1.39), 0.877 | - |

| Model Performance | |||

| AUC (95% CI) | - | 0.984 (0.971–0.997) | 0.989 (0.978–0.999) |

| Hosmer-Lemeshow p | - | 0.837 | 0.925 |

| Nagelkerke R2 | - | 0.792 | 0.825 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Osredkar, J.; Rakusa, M.; Jerin, A.; Štabuc, B.; Zaplotnik, M.; Štupar, S.; Siuka, D. Disrupted Vitamin D Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Free and Bioavailable 25(OH)D as Novel Biomarkers of Hepatic Reserve and Clinical Risk. Molecules 2026, 31, 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020273

Osredkar J, Rakusa M, Jerin A, Štabuc B, Zaplotnik M, Štupar S, Siuka D. Disrupted Vitamin D Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Free and Bioavailable 25(OH)D as Novel Biomarkers of Hepatic Reserve and Clinical Risk. Molecules. 2026; 31(2):273. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020273

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsredkar, Joško, Matej Rakusa, Aleš Jerin, Borut Štabuc, Martin Zaplotnik, Saša Štupar, and Darko Siuka. 2026. "Disrupted Vitamin D Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Free and Bioavailable 25(OH)D as Novel Biomarkers of Hepatic Reserve and Clinical Risk" Molecules 31, no. 2: 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020273

APA StyleOsredkar, J., Rakusa, M., Jerin, A., Štabuc, B., Zaplotnik, M., Štupar, S., & Siuka, D. (2026). Disrupted Vitamin D Metabolism in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Free and Bioavailable 25(OH)D as Novel Biomarkers of Hepatic Reserve and Clinical Risk. Molecules, 31(2), 273. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31020273