Diurnal and Daily Changes in the Levels of Sesquiterpene Lactone and Other Components in Lettuce Post-Harvest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

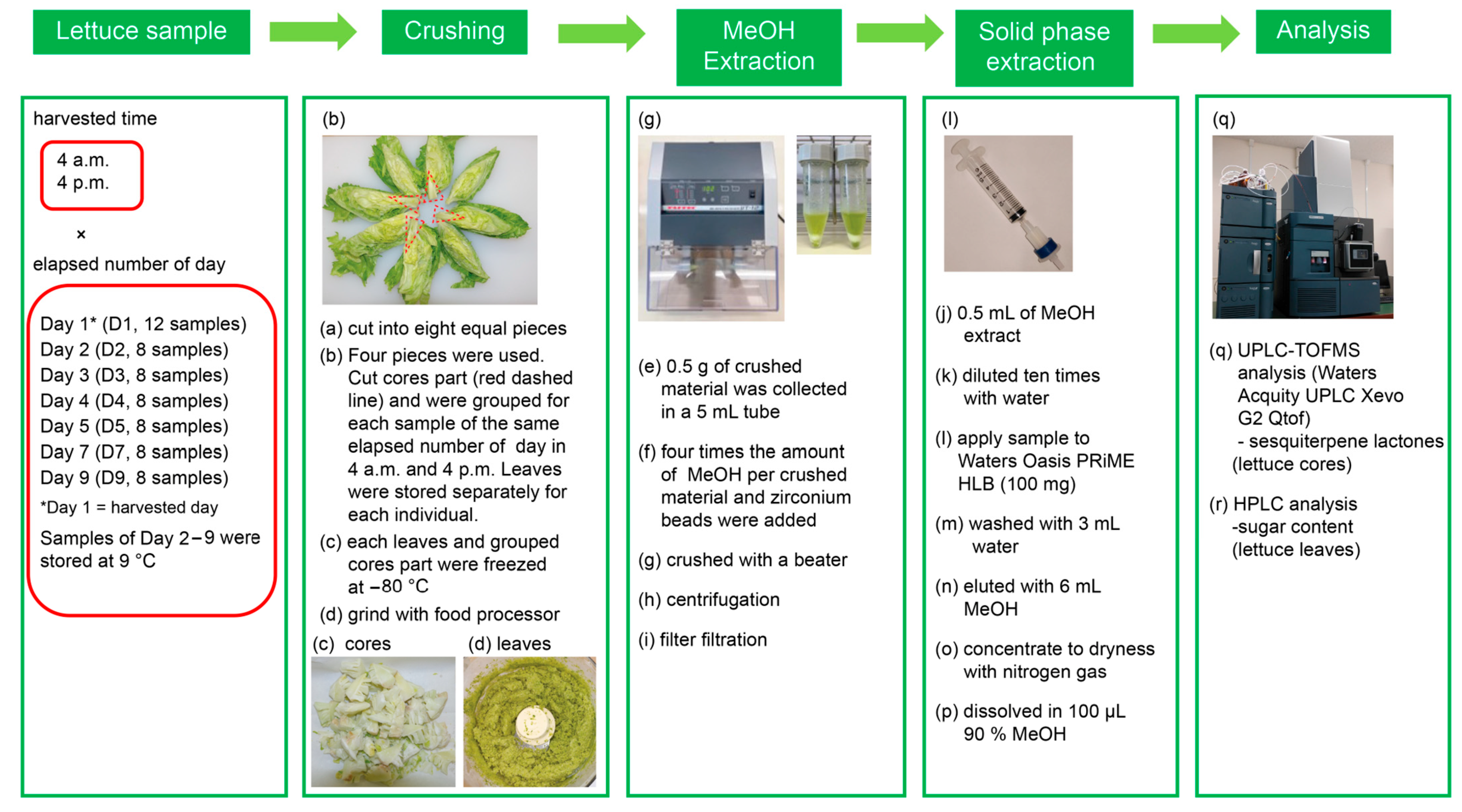

2.1. Lettuce Sample Collection and Processing

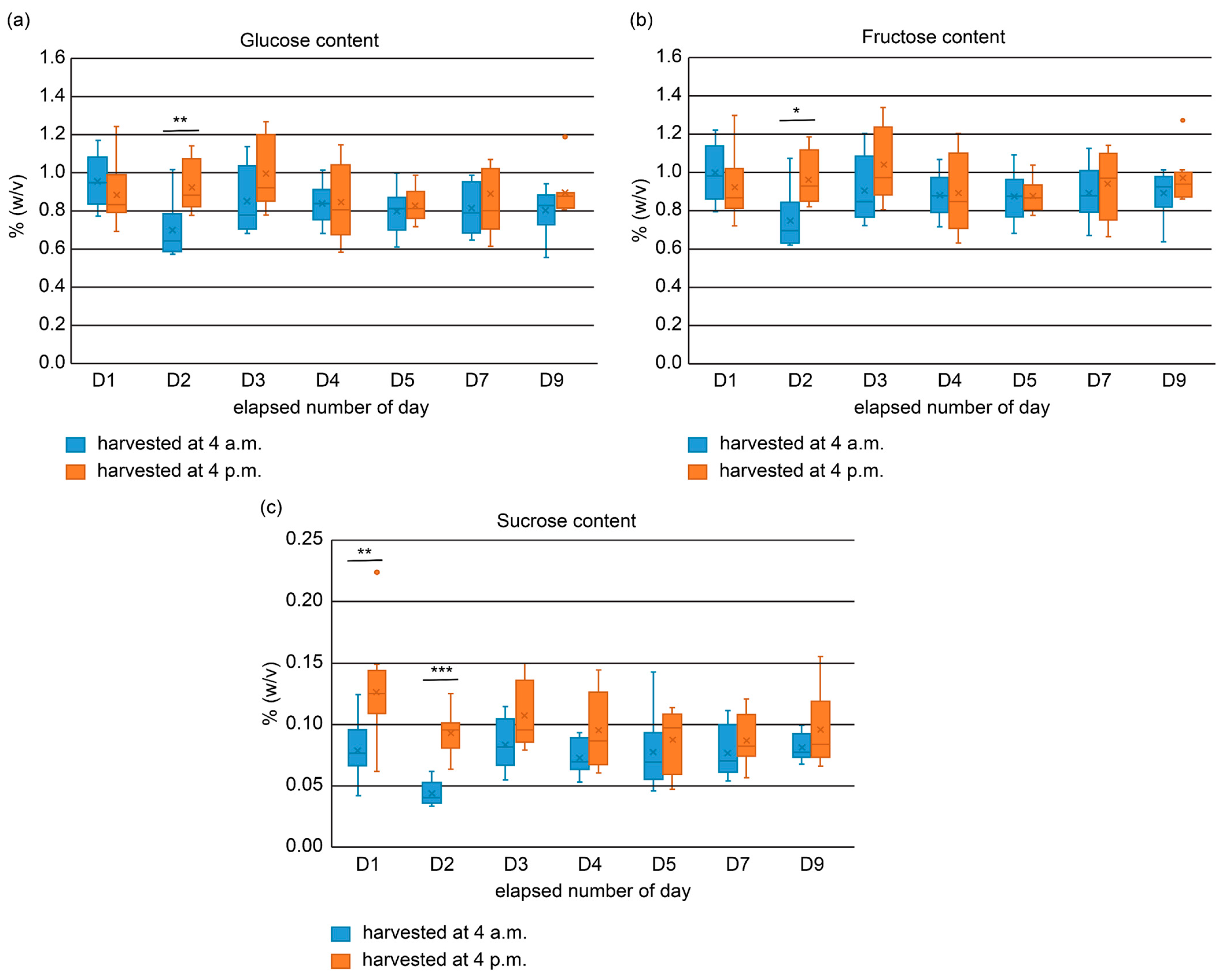

2.2. Quantification of Sugars Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

2.3. Antioxidant Capacity

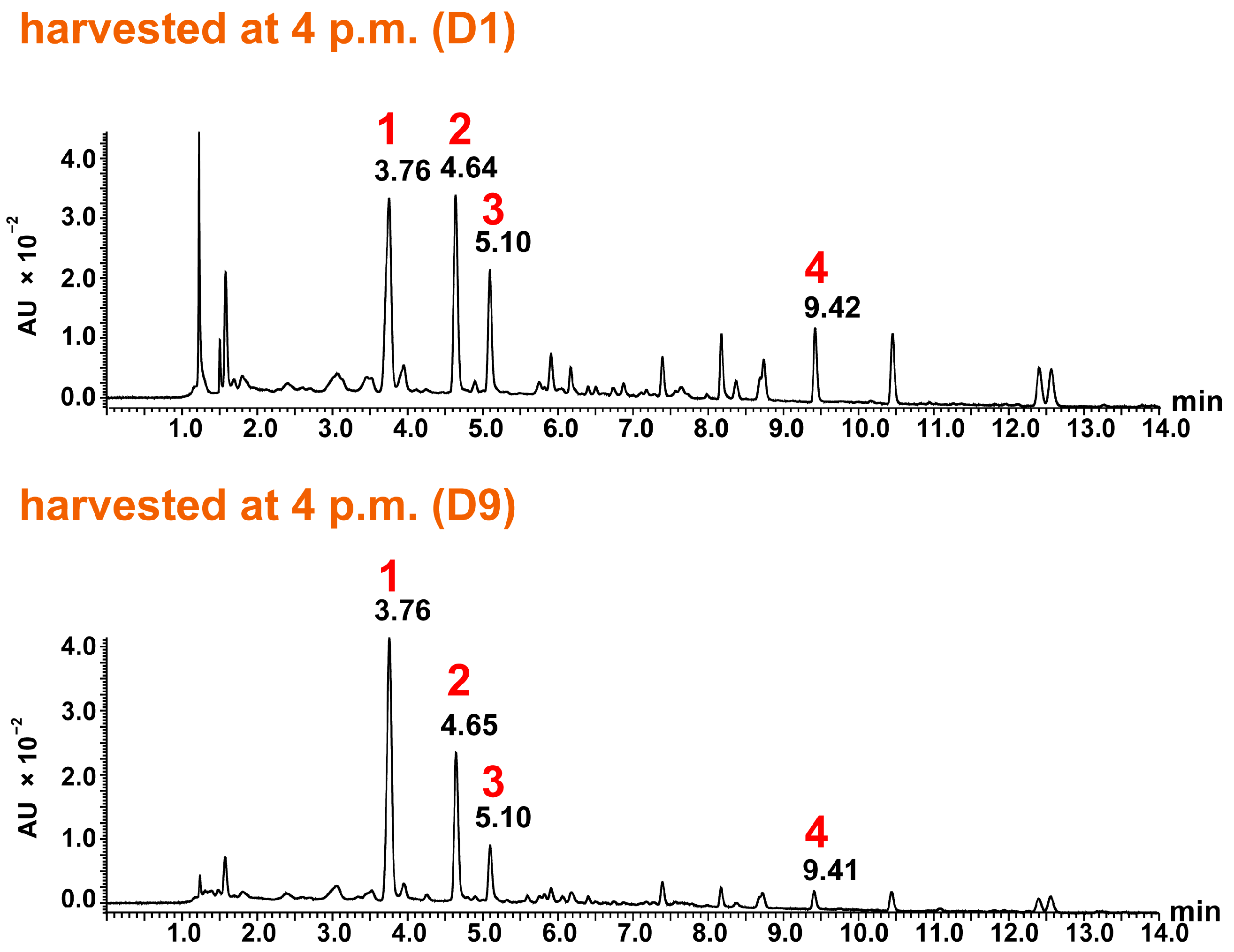

2.4. Identification and Analysis of Sesquiterpene Lactones

2.5. Quantitative Analysis of Sesquiterpene Lactones and Evaluation of Freshness

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals and Reagents

3.2. Plant Specimens

3.3. Extraction of Plant Material

3.4. Sugar Analysis

3.5. H-ORAC Analysis

3.6. UPLC-TOF-MS Analysis

4. Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UPLC-TOF-MS | Ultra-performance liquid chromatography–time of flight-mass spectrometry |

| H-ORAC | Hydrophilic oxygen radical absorbance capacity |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| PDA | Photodiode array |

References

- Brás, T.; Neves, L.A.; Crespo, J.G.; Duarte, M.D.F. Advances in sesquiterpene lactones extraction. TrAC-Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 158, 116838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.R.; Dupont, M.S.; Shepherd, R.; Chan, H.W.-S.; Fenwick, G.R. Relationship between the chemical and sensory properties of exotic salad crops—Coloured lettuce (lactuca sativa) and chicory (cichorium intybus). J. Sci. Food Agric. 1990, 53, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.; Miyase, T.; Umehara, K.; Ueno, A.; Hirano, Y.; Otani, N. Sesquiterpene lactones from Cichorium endivia L. and C. intybus L. and cytotoxic activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 2423–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunning, M.L.; Kendall, P.A.; Stone, M.B.; Stushnoff, F.H.; Stushnoff, C. Effects of Seasonal Variation on Sensory Properties and Total Phenolic Content of Eight Lettuce Cultivars. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testone, G.; Mele, G.; di Giacomo, E.; Tenore, G.C.; Gonnella, M.; Nicolodi, C.; Frugis, G.; Iannelli, M.A.; Arnesi, G.; Schiappa, A.; et al. Transcriptome driven characterization of curly- and smooth-leafed endives reveals molecular differences in the sesquiterpenoid pathway. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domont, J.; Thiblet, M.; Etienne, A.; Alves Dos Santos, H.; Cadalen, T.; Hance, P.; Gagneul, D.; Hilbert, J.-L.; Rambaud, C. CRISPR/Cas9-Targeted Mutagenesis of CiGAS and CiGAO to Reduce Bitterness in Chicory (Cichorium intybus L.). Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beek, T.A.; Montfoort, M.J.; Peper, T.; Posthumus, M.A. Bitter sesquiterpene lactones from Lactuca virosa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 1858–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, F.; Glomb, M.A. Structural and sensory characterization of novel sesquiterpene lactones from iceberg lettuce. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalska, K.; Kisiel, W. Further sesquiterpene lactones and phenolics from Cichorium spinosum. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2007, 35, 714–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, Y.; Abdelwahab, G.; Heraiz, A.A.; Sallam, M.; Othman, A. Exploring sesquiterpene lactones: Structural diversity and antiviral therapeutic insights. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 1970–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, H. Analysis of lactucopicrins (bitter compounds) in lettuce by high-performance liquid chromatography. Bull. Natl. Inst. Veg. Tea Sci. 2010, 9, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakawa, K.; Minami, M.; Nakamura, K.; Matsushima, K.; Nemoto, K. Differences of sesquiterpene lactones content in different leaf parts and head formation stages in lettuce. Hortic. Res. 2009, 8, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLemore, M.; Kathi, S.; Unterschuetz, J.; Mason, T.; Maness, N.; Chrz, D.; Dunn, B.; Fontanier, C.; Hu, B. Impact of Seasonal Temperature Changes on Sesquiterpene Lactone and Sugar Concentrations in Hydroponically Grown Lettuce. HortScience 2025, 60, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gil, M.I.; Yang, Q.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Bioactive compounds in lettuce: Highlighting the benefits to human health and impacts of preharvest and postharvest practices. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehinia, S.; Didaran, F.; Gariepy, Y.; Aliniaeifard, S.; MacPherson, S.; Lefsrud, M. Green Light Enhances the Postharvest Quality of Lettuce During Cold Storage. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Wang, K.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, X.; Yue, F.; Chen, Y. The quality changes and shelf-life of fresh-cut Iceberg lettuce treated by ultrasound and modified atmosphere packages. Acta Hortic. 2021, 1319, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltering, E.J.; Witkowska, I.M. Effects of pre- and postharvest lighting on quality and shelf life of fresh-cut lettuce. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1134, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, M.; Savić, S.; Delcourt, A.; Hilbert, J.-L.; Hance, P.; Dragišić Maksimović, J.; Maksimović, V. Phenolics and sesquiterpene lactones profile of red and green lettuce: Combined effect of cultivar, microbiological fertiliser, and season. Plants 2023, 12, 2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Soluch, A.; Kowalska, I.; Olas, B. Antioxidant and hemostatic properties of preparations from Asteraceae family and their chemical composition-Comparative studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 142, 111982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisaminato, H.; Murata, M.; Homma, S. Relationship between the enzymatic browning and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase activity of cut lettuce, and the prevention of browning by inhibitors of polyphenol biosynthesis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2001, 65, 1016–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.J.; García-Villalba, R.; Garrido, Y.; Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. Untargeted metabolomics approach using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS to explore the metabolome of fresh-cut iceberg lettuce. Metabolomics 2016, 12, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.J.; García-Villalba, R.; Gil, M.I.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A. LC-MS untargeted metabolomics to explain the signal metabolites inducing browning in fresh-cut lettuce. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4526–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozgen, M.; Reese, R.N.; Tulio, A.Z.; Scheerens, J.C.; Miller, A.R. Modified 2,2-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid(ABTS) method to measure antioxidant capacity of selected small fruits and comparison to ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl(DPPH) methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimamura, T.; Matsuura, R.; Tokuda, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Matsufuji, H.; Matsui, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Ukeda, H. Comparison of conventional antioxidant assays for evaluating potencies of natural antioxidants as food additives by collaborative study. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi 2007, 54, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Oki, T.; Takebayashi, J.; Takano-Ishikawa, Y. Extraction efficiency of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants from lyophilized foods using pressurized liquid extraction and manual extraction. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, C1665–C1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, J. Standardization and application of methods to measure antioxidant capacity of foods and functional food components. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi 2019, 66, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kamata, K.; Okada, H.; Ohta, Y. Diurnal and Daily Changes in the Levels of Sesquiterpene Lactone and Other Components in Lettuce Post-Harvest. Molecules 2026, 31, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010080

Kamata K, Okada H, Ohta Y. Diurnal and Daily Changes in the Levels of Sesquiterpene Lactone and Other Components in Lettuce Post-Harvest. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamata, Kazuaki, Hitomi Okada, and Yukari Ohta. 2026. "Diurnal and Daily Changes in the Levels of Sesquiterpene Lactone and Other Components in Lettuce Post-Harvest" Molecules 31, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010080

APA StyleKamata, K., Okada, H., & Ohta, Y. (2026). Diurnal and Daily Changes in the Levels of Sesquiterpene Lactone and Other Components in Lettuce Post-Harvest. Molecules, 31(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010080