Connectivity Effect on Electronic Properties of Azulene–Tetraazapyrene Triads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

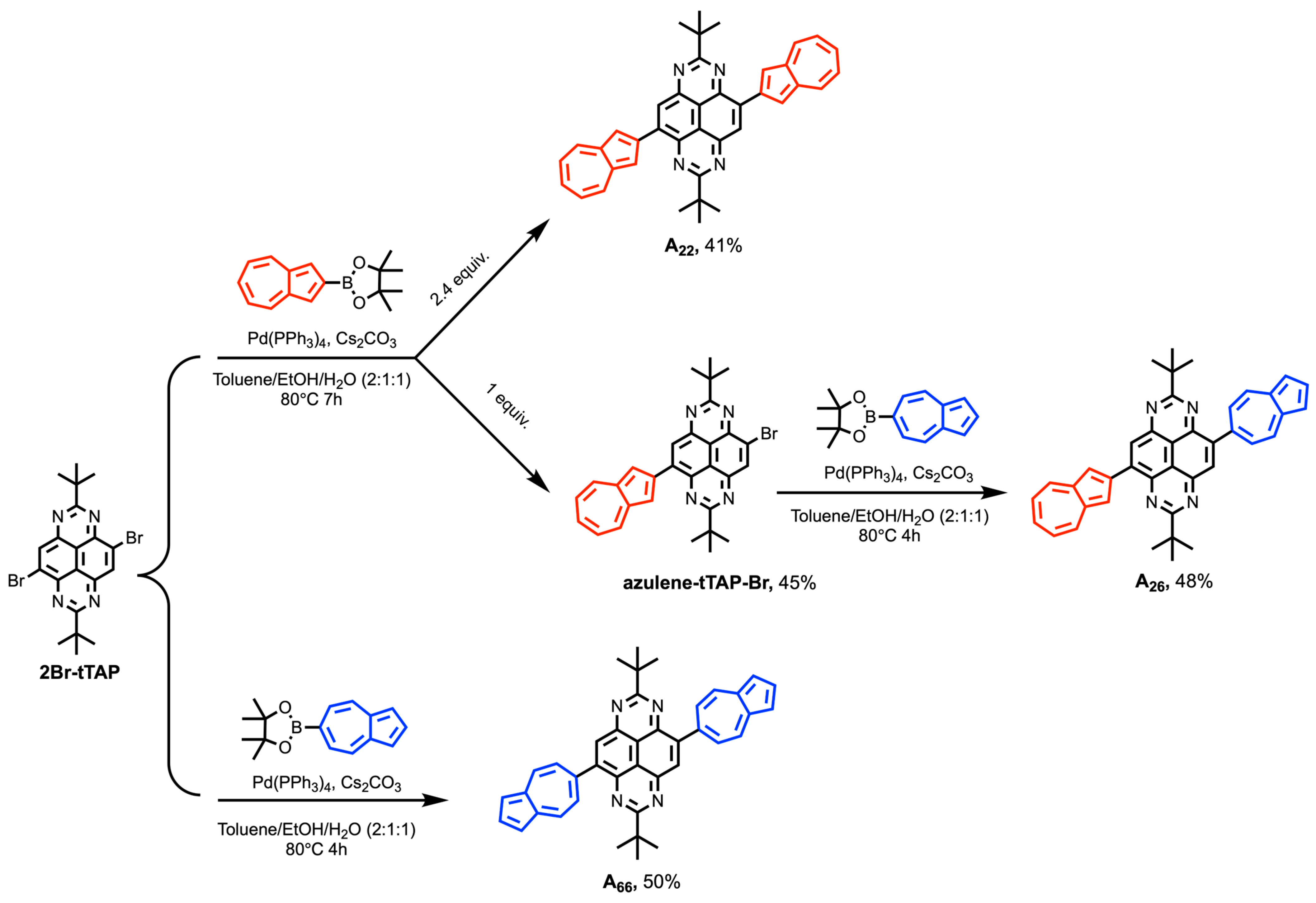

2.1. Synthesis

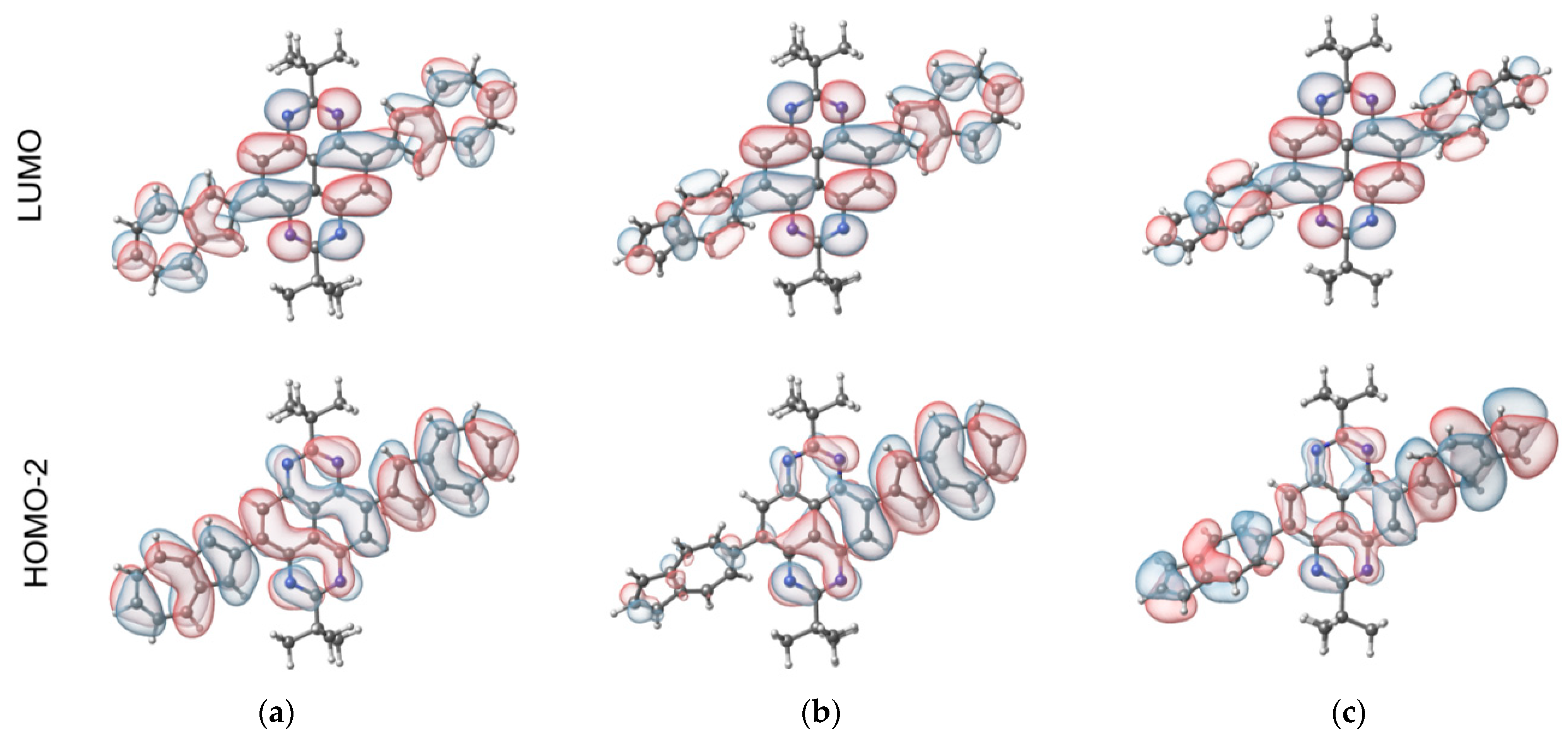

2.2. Optical Properties

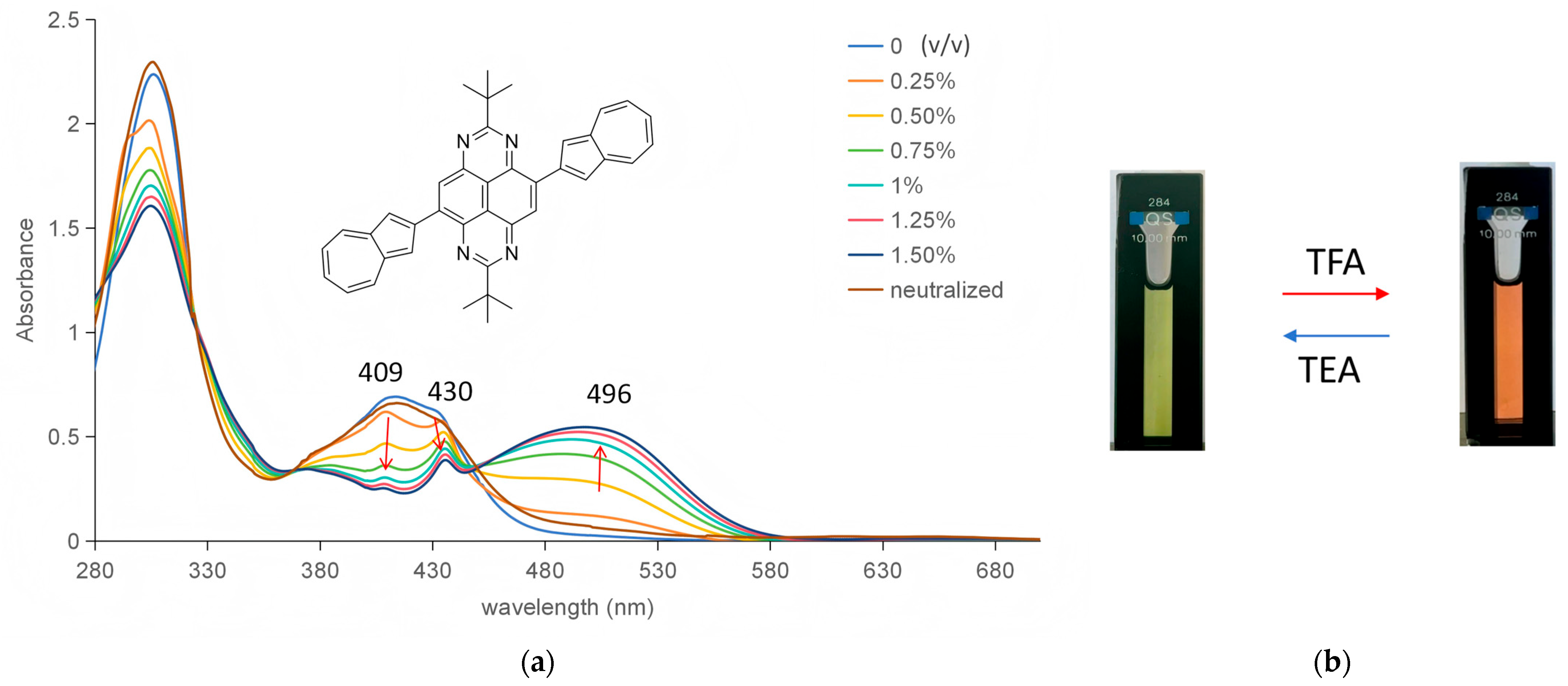

2.3. pH-Responsiveness

2.4. Electrochemical Properties

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zubair, T.; Hasan, M.M.; Ramos, R.S.; Pankow, R.M. Conjugated polymers with near-infrared (NIR) optical absorption: Structural design considerations and applications in organic electronics. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 8188–8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Ou, X.; Xu, W.; Kang, M.; Li, X.; Yan, D.; Kwok, R.T.K.; et al. More Is Better: Dual-Acceptor Engineering for Constructing Second Near-Infrared Aggregation-Induced Emission Luminogens to Boost Multimodal Phototheranostics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 22776–22787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; He, T.; Wang, R.; Ouyang, Y.; Jain, N.; Liu, S.; Kan, B.; Shang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Regulate the Singlet–Triplet Energy Gap by Spatially Separating HOMO and LUMO for High Performance Organic Photovoltaic Acceptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 137, e202506357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Huang, Y.-H.; Gong, S.; Li, P.; Lee, W.-K.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, C.; Wu, C.-C.; Yang, C. An unsymmetrical thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitter enables orange-red electroluminescence with 31.7% external quantum efficiency. Mater. Horiz. 2021, 8, 2286–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnola, P.J.; Loew, L.M. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy for visualizing biomolecular arrays in cells, tissues and organisms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 1356–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cao, S.; Sun, X.; Su, H.; Li, H.; Liu, G.; Luo, X.; Wu, F. Self-Assembled Naphthalimide Conjugated Porphyrin Nanomaterials with D–A Structure for PDT/PTT Synergistic Therapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2020, 31, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yue, B.; Wu, B.; Sun, R.; Qu, S.; Zhu, L. Multiwavelength Anti-Kasha’s Rule Emission on Self-Assembly of Azulene-Functionalized Persulfurated Arene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 22511–22518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Hou, B.; Gao, X. Azulene-Based π-Functional Materials: Design, Synthesis, and Applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 1737–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Aschauer, U.; Decurtins, S.; Feurer, T.; Haner, R.; Liu, S.-X. Merging of Azulene and Perylene Diimide for Optical pH Sensors. Molecules 2023, 28, 6694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nakayama, K.-i.; Ohba, Y.; Katagiri, H. Terazulene: A High-Performance n-Type Organic Field-Effect Transistor Based on Molecular Orbital Distribution Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 19095–19098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Ge, C.; Yang, X.; Gao, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, X. Biazulene diimides: A new building block for organic electronic materials. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 6701–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, M.; Amir, E.; Amir, R.J.; Hawker, C.J. Azulene-based conjugated polymers: Unique seven-membered ring connectivity leading to stimuli-responsiveness. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3, 2721–2725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Zhang, J.; Cai, S.; Xiang, J.; Yang, X.; Gao, X. Azulene-Indole Fused Polycyclic Heteroaromatics. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 26, e202201347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ge, C.; Hou, B.; Xin, H.; Gao, X. Incorporation of 1,3-Free-2,6-Connected Azulene Units into the Backbone of Conjugated Polymers: Improving Proton Responsiveness and Electrical Conductivity. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1360–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Blacque, O.; Venkatesan, K. Impact of 2,6-connectivity in azulene: Optical properties and stimuli responsive behavior. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 7400–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koide, T.; Takesue, M.; Murafuji, T.; Satomi, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Kawamata, J.; Terai, K.; Suzuki, M.; Yamada, H.; Shiota, Y.; et al. An Azulene-Fused Tetracene Diimide with a Small HOMO–LUMO Gap. ChemPlusChem 2017, 82, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, B.; Jiang, K.; Sun, S.; Ke, C.; Kymakis, E.; Zhuang, X. Azulene-Based Molecules, Polymers, and Frameworks for Optoelectronic and Energy Applications. Small Methods 2020, 4, 2000628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H.; Duan, X.; Zheng, R.; Xie, F.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Z.; Han, R.; Lei, Z.; Hu, J.Y. Two Isomeric Azulene-Decorated Naphthodithiophene Diimide-based Triads: Molecular Orbital Distribution Controls Polarity Change of OFETs Through Connection Position. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23225–23235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.N.; Png, Z.M.; Xu, J. Azulene in Polymers and Their Properties. Chem. Asian J. 2020, 15, 1904–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumaitre, C.; Morin, J.-F. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons as Potential Building Blocks for Organic Solar Cells. Chem. Rec. 2019, 19, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pokorný, V.; Žonda, M.; Liu, J.-C.; Zhou, P.; Chahib, O.; Glatzel, T.; Häner, R.; Decurtins, S.; Liu, S.-X.; et al. Individual Assembly of Radical Molecules on Superconductors: Demonstrating Quantum Spin Behavior and Bistable Charge Rearrangement. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 3403–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drechsel, C.; Li, C.; Liu, J.C.; Liu, X.; Haner, R.; Decurtins, S.; Aschauer, U.; Liu, S.X.; Meyer, E.; Pawlak, R. Discharge and electron correlation of radical molecules in a supramolecular assembly on superconducting Pb(111). Nanoscale Horiz. 2025, 10, 2365–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Nazari Haghighi Pashaki, M.; Frey, H.-M.; Hauser, A.; Decurtins, S.; Cannizzo, A.; Feurer, T.; Haner, R.; Aschauer, U.; Liu, S.-X. Photoinduced asymmetric charge trapping in a symmetric tetraazapyrene-fused bis(tetrathiafulvalene) conjugate. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12715–12722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Kaspar, C.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.-C.; Chahib, O.; Glatzel, T.; Häner, R.; Aschauer, U.; Decurtins, S.; Liu, S.-X.; et al. Strong signature of electron-vibration coupling in molecules on Ag(111) triggered by tip-gated discharging. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Aschauer, U.; Decurtins, S.; Feurer, T.; Häner, R.; Liu, S.X. Effect of tert-butyl groups on electronic communication between redox units in tetrathiafulvalene-tetraazapyrene triads. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 12972–12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geib, S.; Martens, S.C.; Zschieschang, U.; Lombeck, F.; Wadepohl, H.; Klauk, H.; Gade, L.H. 1,3,6,8-Tetraazapyrenes: Synthesis, Solid-State Structures, and Properties as Redox-Active Materials. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 6107–6116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Hu, W.; Dong, H. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-based organic semiconductors: Ring-closing synthesis and optoelectronic properties. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 2411–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Negrete-Vergara, C.; Langenegger, S.M.; Malaspina, L.A.; Grabowsky, S.; Häner, R.; Liu, S.-X. Intramolecular exciplex formation between pyrene and tetraazapyrene in supramolecular assemblies. Org. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 6094–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, X.; Decurtins, S.; Liu, S.X. Cascade C-H Halogenation of Tetraazapyrene with Iodine Halides. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 11434–11439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, M.; Iba, S.; Ota, H.; Takai, K. Azulene-Fused Linear Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons with Small Bandgap, High Stability, and Reversible Stimuli Responsiveness. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5585–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukazawa, M.; Takahashi, F.; Yorimitsu, H. Sodium-Promoted Borylation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4613–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, M.; Bylaska, E.J.; Govind, N.; Kowalski, K.; Straatsma, T.P.; Van Dam, H.J.J.; Wang, D.; Nieplocha, J.; Apra, E.; Windus, T.L.; et al. NWChem: A comprehensive and scalable open-source solution for large scale molecular simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 1477–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Majani, S.; Zhang, J.; Langenegger, S.M.; Decurtins, S.; Aschauer, U.; Liu, S.-X. Connectivity Effect on Electronic Properties of Azulene–Tetraazapyrene Triads. Molecules 2026, 31, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010002

Liu X, Majani S, Zhang J, Langenegger SM, Decurtins S, Aschauer U, Liu S-X. Connectivity Effect on Electronic Properties of Azulene–Tetraazapyrene Triads. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xinyi, Souren Majani, Jian Zhang, Simon M. Langenegger, Silvio Decurtins, Ulrich Aschauer, and Shi-Xia Liu. 2026. "Connectivity Effect on Electronic Properties of Azulene–Tetraazapyrene Triads" Molecules 31, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010002

APA StyleLiu, X., Majani, S., Zhang, J., Langenegger, S. M., Decurtins, S., Aschauer, U., & Liu, S.-X. (2026). Connectivity Effect on Electronic Properties of Azulene–Tetraazapyrene Triads. Molecules, 31(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010002