Viniferin-Rich Phytocomplex from Vitis vinifera L. Plant Cell Culture Mitigates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Characterization of Vitis vinifera L. Standardized Phytocomplex Obtained from Cell Culture Suspensions

2.1.1. Development and Preparation of V. vinifera L. Standardized Phytocomplex (VP)

2.1.2. UPLC-DAD and LC-MS Analysis

2.2. Effect of VP on an In Vitro Model of Neuroinflammation

2.2.1. Suppression of Microglia Proinflammatory Phenotype by VP

2.2.2. Effect of VP on Microglia Cell Viability

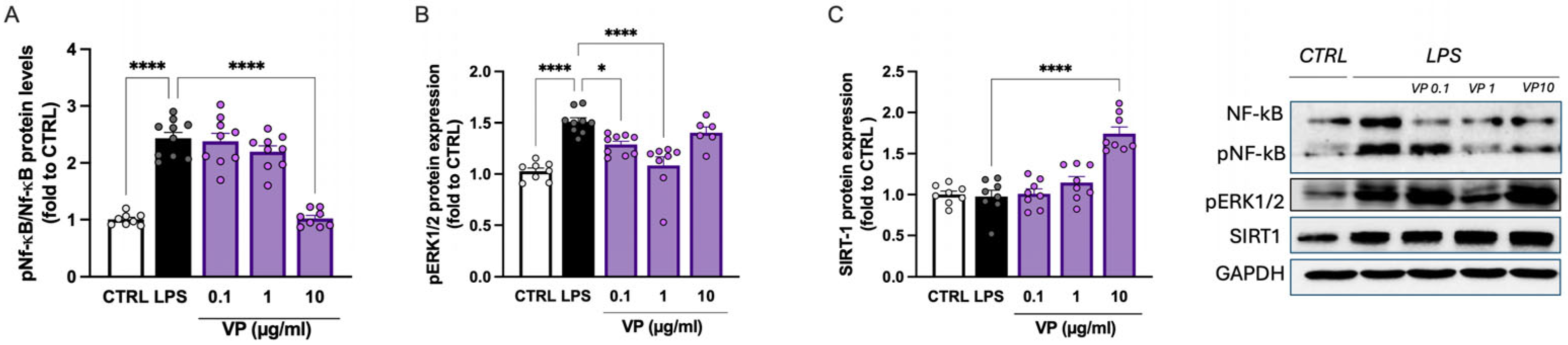

2.2.3. Modulation of Neuroinflammation Markers by VP

2.3. Pharmacological Profile of VP Nanocellulose Formulations

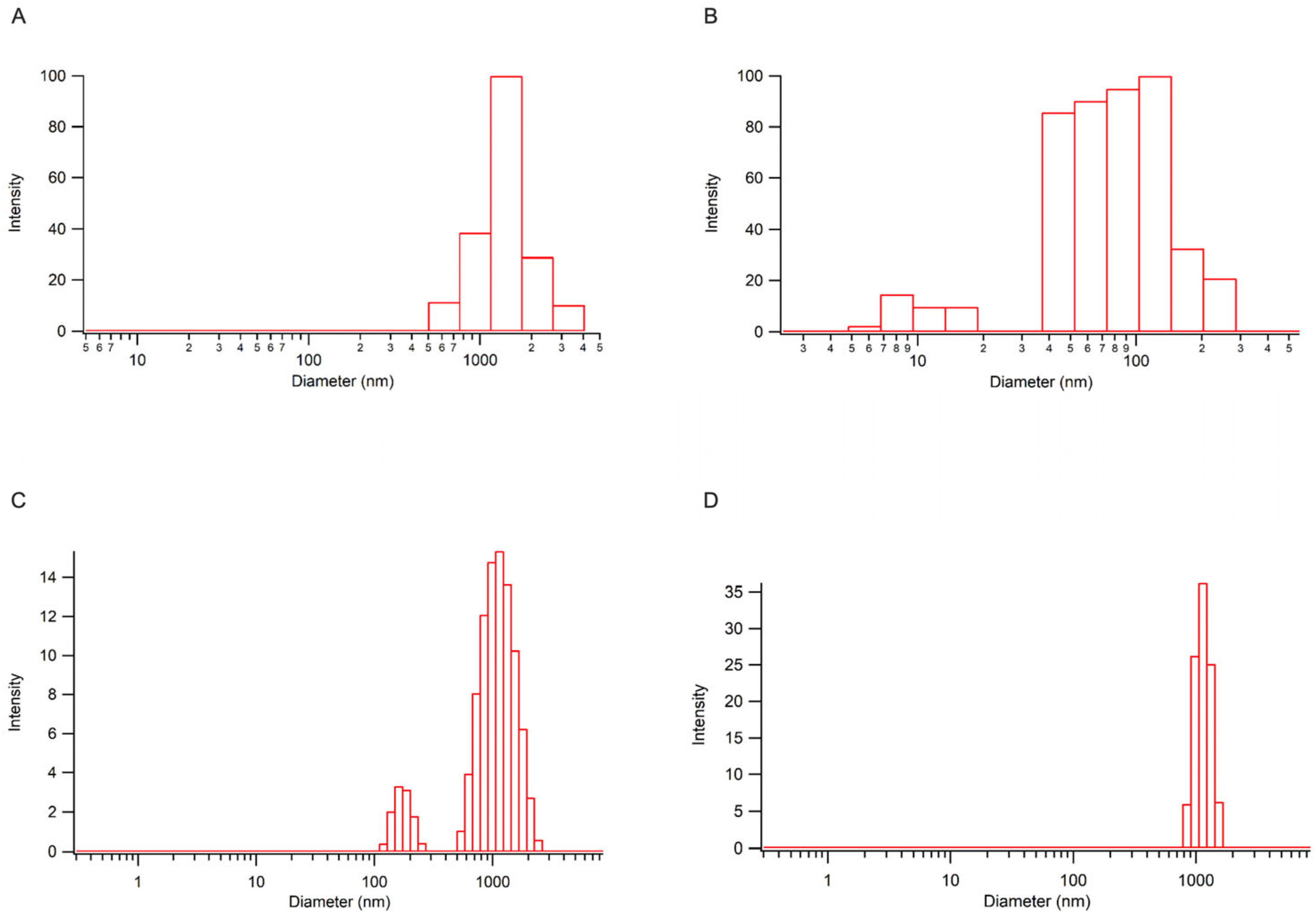

2.3.1. Analysis of VP-CNC Formulations

2.3.2. Attenuation of Proinflammatory Morphology by VP-CNC Nanoformulations

2.3.3. Improvement of Microglia Cell Viability by VP Nanoformulations

2.3.4. Effect of VP-CNC Nanoformulation on pERK1/2 and SIRT1 Levels

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Vitis vinifera L. Phytocomplex (VP) from Cell Culture Suspensions

4.2. UPLC-DAD and LC-MS Analysis of Vitis vinifera L. Standardized Phytocomplex (VP)

4.2.1. Sample Preparation

4.2.2. UPLC–DAD Conditions

4.2.3. LC–MS Analysis

4.3. Synthesis CNC (+)

4.4. Preparation of VP-CNC Nanoformulations

4.5. BV2 Cell Culture

4.6. Treatments

4.7. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) Assay

4.8. Cell Counting and Morphology

4.9. Western Blot Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKT | activation of protein kinase B |

| CNC | cellulose nanocrystal |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CSF1R | colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinases |

| LPS | bacterial lipopolysaccharide from Gram- |

| MAPK | mitogen activated protein kinase |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor κB |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SIRT1 | silent information regulator sirtuin 1 |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| VP | Vitis vinifera L. phytocomplex |

References

- Waisman, A.; Liblau, R.S.; Becher, B. Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses in the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamu, A.; Li, S.; Gao, F.; Xue, G. The Role of Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Understanding and Future Therapeutic Targets. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1347987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiSabato, D.J.; Quan, N.; Godbout, J.P. Neuroinflammation: The Devil Is in the Details. J. Neurochem. 2016, 139, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kölliker-Frers, R.; Udovin, L.; Otero-Losada, M.; Kobiec, T.; Herrera, M.I.; Palacios, J.; Razzitte, G.; Capani, F. Neuroinflammation: An Integrating Overview of Reactive-Neuroimmune Cell Interactions in Health and Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9999146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Kim, B.; Abdulkhaliq, A.A.; Ren, J.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Borai, A.; Khan, J.; Pratico, D. Dual Role of Microglia in Neuroinflammation and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2025, 216, 107133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Barres, B.A. Microglia and Macrophages in Brain Homeostasis and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Ma, Z.; Chen, X.; Shu, S. Microglia Activation in Central Nervous System Disorders: A Review of Recent Mechanistic Investigations and Development Efforts. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.H. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Roles of Microglia and Astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Mechanism and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.D.; Yong, V.W. Neuroinflammation across Neurological Diseases. Science 2025, 388, eadx0043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goufo, P.; Singh, R.K.; Cortez, I. A Reference List of Phenolic Compounds (Including Stilbenes) in Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Roots, Woods, Canes, Stems, and Leaves. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.D.; Li, J.; Xiong, R.G.; Saimaiti, A.; Huang, S.Y.; Wu, S.X.; Yang, Z.J.; Shang, A.; Zhao, C.N.; Gan, R.Y.; et al. Bioactive Compounds, Health Benefits and Food Applications of Grape. Foods 2022, 11, 2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Deng, X.; Lei, Y.; Xie, S.; Guo, S.; Ren, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, T. Foliar-Sprayed Manganese Sulfate Improves Flavonoid Content in Grape Berry Skin of Cabernet Sauvignon (Vitis Vinifera L.) Growing on Alkaline Soil and Wine Chromatic Characteristics. Food Chem. 2020, 314, 126182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetik, F.; Civelek, S.; Cakilcioglu, U. Traditional Uses of Some Medicinal Plants in Malatya (Turkey). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, M.; Mahmood, A.; Maqbool, M. Indigenous Knowledge of Medicinal Plants from Sudhanoti District (AJK), Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 168, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassiri-Asl, M.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Review of the Pharmacological Effects of Vitis Vinifera (Grape) and Its Bioactive Constituents: An Update. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, B.V.S.; Sudhakar, M.; Anisha, M. Neuroprotective Role of Hydroalcoholic Extract of Vitis Vinifera against Aluminium-Induced Oxidative Stress in Rat Brain. Neurotoxicology 2014, 41, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazos-Tomas, C.C.; Cruz-Venegas, A.; Pérez-Santiago, A.D.; Sánchez-Medina, M.A.; Matías-Pérez, D.; García-Montalvo, I.A. Vitis Vinifera: An Alternative for the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Oleo Sci. 2020, 69, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasteva, G.; Georgiev, V.; Pavlov, A. Recent Applications of Plant Cell Culture Technology in Cosmetics and Foods. Eng. Life Sci. 2020, 21, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Slavov, A.; Vasileva, I.; Pavlov, A. Plant Cell Culture as Emerging Technology for Production of Active Cosmetic Ingredients. Eng. Life Sci. 2018, 18, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, O.; Hädicke, E.; Koltzenburg, S.; Müller-Plathe, F.; Müller-Plathe, F. Hydrophilicity and Lipophilicity of Cellulose Crystal Surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 3822–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, B.; Medronho, B.; Alves, L.; Norgren, M.; Nordenskiöld, L. Hydrophobic Interactions Control the Self-Assembly of DNA and Cellulose. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2021, 54, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Chauhan, S. Cellulose Nanocrystals Based Delivery Vehicles for Anticancer Agent Curcumin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 842–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazeau, K.; Wyszomirski, M. Modelling of Congo Red Adsorption on the Hydrophobic Surface of Cellulose Using Molecular Dynamics. Cellulose 2012, 19, 1495–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, C.C.; Fernández-Prieto, S.; De Borggraeve, W.M. Ball Milling: A Green Technology for the Preparation and Functionalisation of Nanocellulose Derivatives. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagiotti, G.; Salvatore, A.; Toniolo, G.; Caselli, L.; Di Vito, M.; Cacaci, M.; Contiero, L.; Gori, T.; Maggini, M.; Sanguinetti, M.; et al. Metal-Free Antibacterial Additives Based on Graphene Materials and Salicylic Acid: From the Bench to Fabric Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 26288–26298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, P.; Tamberi, L.; Tasca, E.; Giacomazzo, G.E.; Martinez, M.; Severi, M.; Marradi, M.; Cicchi, S.; Moya, S.; Biagiotti, G.; et al. The B & B Approach: Ball-Milling Conjugation of Dextran with Phenylboronic Acid (PBA)-Functionalized BODIPY. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricomi, J.; Cacaci, M.; Biagiotti, G.; Caselli, L.; Niccoli, L.; Torelli, R.; Gabbani, A.; Di Vito, M.; Pineider, F.; Severi, M.; et al. Ball Milled Glyco-Graphene Oxide Conjugates Markedly Disrupted Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 10190–10199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hove, H.; De Feo, D.; Greter, M.; Becher, B. Central Nervous System Macrophages in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 43, 589–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colonna, M.; Butovsky, O. Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 441–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonetti, V.; Anceschi, L.; Brighenti, V.; Corsi, L.; Governa, P.; Manetti, F.; Pellati, F.; Galeotti, N. Cannabidiol-Rich Non-Psychotropic Cannabis Sativa L. Oils Attenuate Peripheral Neuropathy Symptoms by Regulation of CB2-Mediated Microglial Neuroinflammation. Phytother. Res. 2022, 37, 1924–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, E.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Piazza, S.; Manzoni, Y.; Brunelli, C.; Fumagalli, M.; Magnavacca, A.; Martinelli, G.; Colombo, F.; Casiraghi, A.; et al. Vitis Vinifera L. Leaf Extract Inhibits In Vitro Mediators of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress Involved in Inflammatory-Based Skin Diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acero, N.; Manrique, J.; Muñoz-Mingarro, D.; Martínez Solís, I.; Bosch, F. Vitis Vinifera L. Leaves as a Source of Phenolic Compounds with Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Potential. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.M.; Ryan, G.R.; Hapel, A.J.; Dominguez, M.G.; Russell, R.G.; Kapp, S.; Sylvestre, V.; Stanley, E.R. Targeted Disruption of the Mouse Colony-Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor Gene Results in Osteopetrosis, Mononuclear Phagocyte Deficiency, Increased Primitive Progenitor Cell Frequencies, and Reproductive Defects. Blood 2002, 99, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, J.S.C.; Ley, S.C. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in Innate Immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Bai, Y.; Jia, H.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, Z. Role and Mechanisms of the NF-ĸB Signaling Pathway in Various Developmental Processes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, D.; Bhandari, S.; Maity, S.; Mahapatra, S.K.; Rajasekaran, S. Activation of ERK/NF-KB Pathways Contributes to the Inflammatory Response in Epithelial Cells and Macrophages Following Manganese Exposure. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 203, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jia, Y.; Tie, J.; Hu, D. Regulation of SIRT1 and Its Roles in Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 831168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, F.; Hoberg, J.E.; Ramsey, C.S.; Keller, M.D.; Jones, D.R.; Frye, R.A.; Mayo, M.W. Modulation of NF-KappaB-Dependent Transcription and Cell Survival by the SIRT1 Deacetylase. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Wang, J.G.; Xiao, D.M.; Fan, M.; Wang, D.P.; Xiong, J.Y.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, S.L. Resveratrol Inhibits Interleukin 1β-Mediated Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in Articular Chondrocytes by Activating SIRT1 and Thereby Suppressing Nuclear Factor-ΚB Activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 674, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Fan, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Chang, Y.; Yang, P.; Qiu, S.; Chen, T.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z. TIM4-TIM1 Interaction Modulates Th2 Pattern Inflammation through Enhancing SIRT1 Expression. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 40, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Han, D.; Hong, J.; Yang, N.; He, J.; Peng, R.; Mi, X.; Kuang, C.; et al. Baicalin Ameliorates Cognitive Impairment and Protects Microglia from LPS-Induced Neuroinflammation via the SIRT1/HMGB1 Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 4751349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Li, D.; Wei, C.; Liu, L.; Xin, Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, R. The Relationship between SIRT1 and Inflammation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1465849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Mascarenhas, R.; Harish, H.M.; Gowda, Y.; Lakshmaiah, V.V.; Nagella, P.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; Almaghasla, M.I.; Rezk, A.A.S. Stilbenes, a Versatile Class of Natural Metabolites for Inflammation-An Overview. Molecules 2023, 28, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howitz, K.T.; Bitterman, K.J.; Cohen, H.Y.; Lamming, D.W.; Lavu, S.; Wood, J.G.; Zipkin, R.E.; Chung, P.; Kisielewski, A.; Zhang, L.L.; et al. Small Molecule Activators of Sirtuins Extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae Lifespan. Nature 2003, 425, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogina, B.; Tissenbaum, H.A. SIRT1, Resveratrol and Aging. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1393181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.W.; Nakamoto, Y.; Hisatome, T.; Yoshida, S.; Miyazaki, H. Resveratrol and Its Dimers ε-Viniferin and δ-Viniferin in Red Wine Protect Vascular Endothelial Cells by a Similar Mechanism with Different Potency and Efficacy. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.W.; Wu, C.W.; Kokubu, D.; Yoshida, S.; Miyazaki, H. ε-Viniferin Is More Effective than Resveratrol in Promoting Favorable Adipocyte Differentiation with Enhanced Adiponectin Expression and Decreased Lipid Accumulation. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 25, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khawand, T.; Courtois, A.; Valls, J.; Richard, T.; Krisa, S. A Review of Dietary Stilbenes: Sources and Bioavailability. Phytochem. Rev. 2018, 17, 1007–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaumont, P.; Courtois, A.; Atgié, C.; Richard, T.; Krisa, S. In the Shadow of Resveratrol: Biological Activities of Epsilon-Viniferin. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 78, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Rahman, L.; Kim, S.H.; Cao, J.; Arjuna, A.; Lallo, S.; Jhun, B.H.; Yoo, J.W. Recent Advances of Nanocellulose in Drug Delivery Systems. J. Pharm. Investig. 2020, 50, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian, A.; Parsian, H.; Majidinia, M.; Rahimi, M.; Mir, S.M.; Samadi Kafil, H.; Shafiei-Irannejad, V.; Kheyrollah, M.; Ostadi, H.; Yousefi, B. Nanocrystalline Cellulose: Preparation, Physicochemical Properties, and Applications in Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xia, M.; Du, H.; Lin, Z.; Li, B.; Liu, H. Nanocellulose-Based Composite Materials Used in Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2022, 14, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamborg, O.L.; Miller, R.A.; Ojima, K. Nutrient Requirements of Suspension Cultures of Soybean Root Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1968, 50, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Qiao, M.; Ren, X.; Huang, T.S.; Buschle-Diller, G. Antibacterial Membranes Based on Chitosan and Quaternary Ammonium Salts Modified Nanocrystalline Cellulose. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2017, 28, 1629–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonetti, V.; Pressi, G.; Bertaiola, O.; Guarnerio, C.; Mandrone, M.; Chiocchio, I.; Galeotti, N. Attenuation of Neuroinflammation in Microglia Cells by Extracts with High Content of Rosmarinic Acid from in Vitro Cultured Melissa Officinalis L. Cells. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 220, 114969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videtta, G.; Sasia, C.; Galeotti, N. High Rosmarinic Acid Content Melissa Officinalis L. Phytocomplex Modulates Microglia Neuroinflammation Induced by High Glucose. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeotti, N.; Ghelardini, C.; Zoppi, M.; Del Bene, E.; Raimondi, L.; Beneforti, E.; Bartolini, A. Hypofunctionality of Gi Proteins as Aetiopathogenic Mechanism for Migraine and Cluster Headache. Cephalalgia 2001, 21, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motulsky, H.J.; Brown, R.E. Detecting Outliers When Fitting Data with Nonlinear Regression—A New Method Based on Robust Nonlinear Regression and the False Discovery Rate. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Videtta, G.; Sasia, C.; Quadrino, S.; Bertaiola, O.; Guarnerio, C.; Bianchi, E.; Biagiotti, G.; Richichi, B.; Cicchi, S.; Pressi, G.; et al. Viniferin-Rich Phytocomplex from Vitis vinifera L. Plant Cell Culture Mitigates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells. Molecules 2026, 31, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010196

Videtta G, Sasia C, Quadrino S, Bertaiola O, Guarnerio C, Bianchi E, Biagiotti G, Richichi B, Cicchi S, Pressi G, et al. Viniferin-Rich Phytocomplex from Vitis vinifera L. Plant Cell Culture Mitigates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010196

Chicago/Turabian StyleVidetta, Giacomina, Chiara Sasia, Sofia Quadrino, Oriana Bertaiola, Chiara Guarnerio, Elisa Bianchi, Giacomo Biagiotti, Barbara Richichi, Stefano Cicchi, Giovanna Pressi, and et al. 2026. "Viniferin-Rich Phytocomplex from Vitis vinifera L. Plant Cell Culture Mitigates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells" Molecules 31, no. 1: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010196

APA StyleVidetta, G., Sasia, C., Quadrino, S., Bertaiola, O., Guarnerio, C., Bianchi, E., Biagiotti, G., Richichi, B., Cicchi, S., Pressi, G., & Galeotti, N. (2026). Viniferin-Rich Phytocomplex from Vitis vinifera L. Plant Cell Culture Mitigates Neuroinflammation in BV2 Microglia Cells. Molecules, 31(1), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010196