Obtaining and Studying the Properties of Composite Materials from ortho-, meta-, para-Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

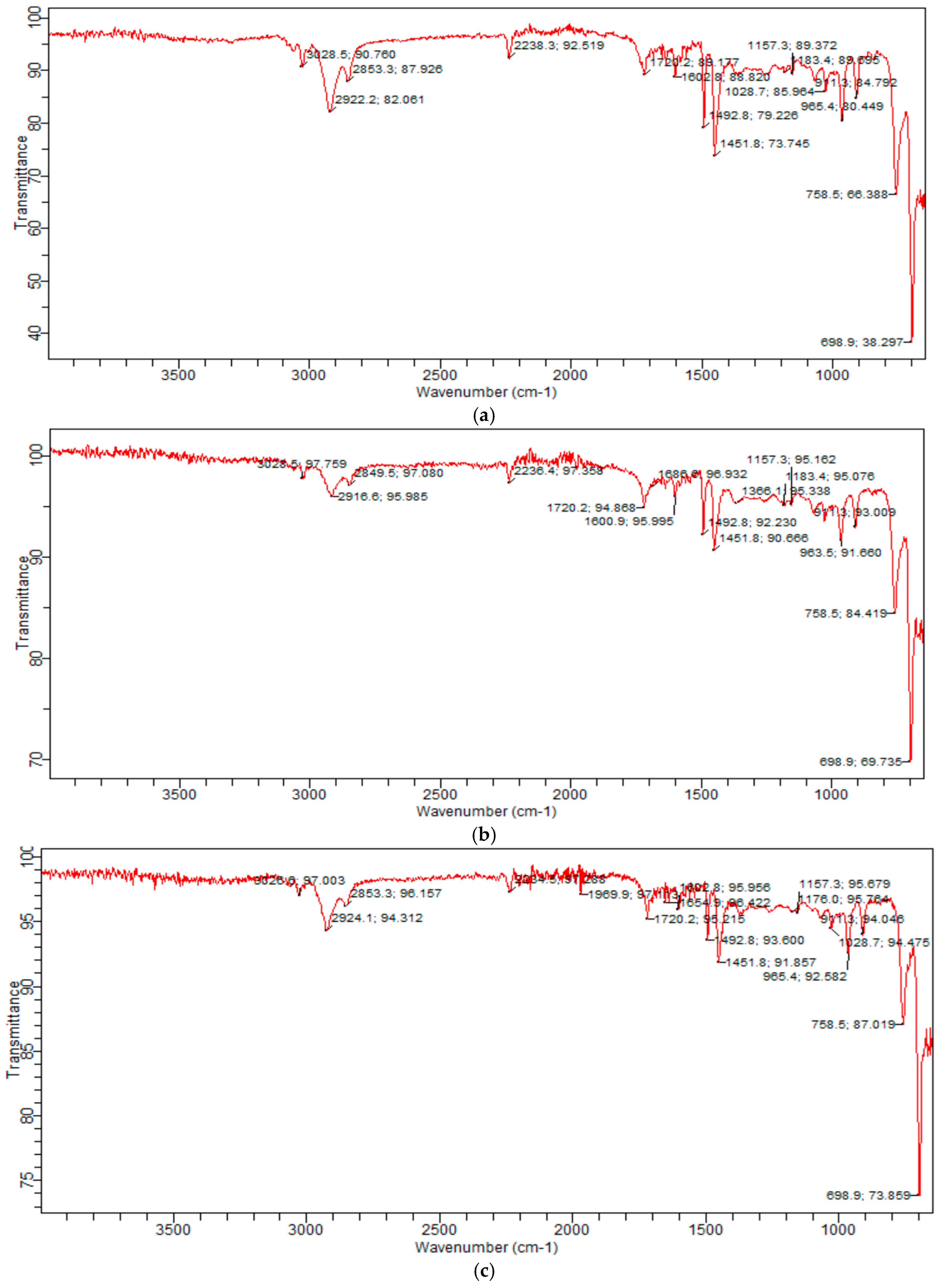

2.1. Identification of Compositions of o-, m-, p-Carboxyphenylmaleimide/ABS

2.2. Physical and Mechanical Parameters of CM Based on o-, m-, p-CPhMI/ABS

2.3. Antibacterial Evaluation

2.4. In Silico Studies

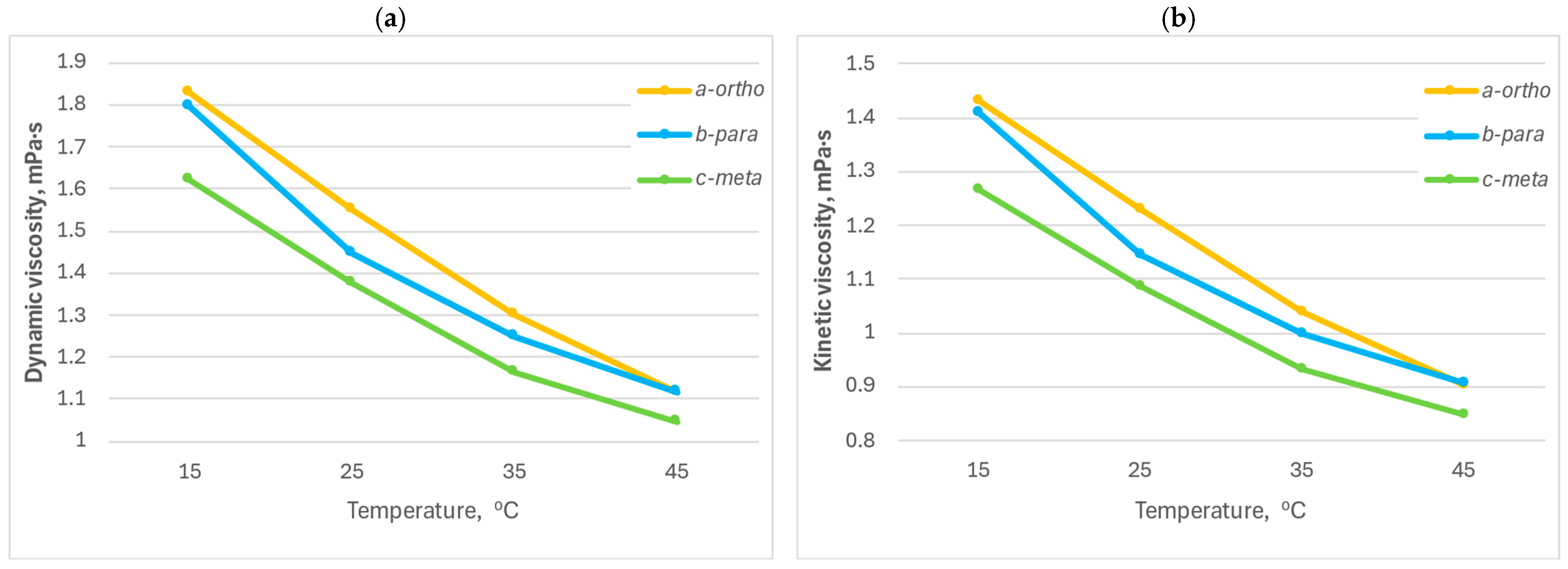

2.5. Study of Dynamic and Kinematic Viscosity of the Composition

2.6. Study of Thermal Properties of the Composition

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Instruments

3.3. The Study of Antibacterial Properties of CM Based on o-, m-, p-CPhMI/ABS

3.4. Antibacterial Methodology

3.5. In Silico Studies

3.6. Study of Viscosity of the Composition

3.7. Thermal Analysis of the Composition (DTA/TGA)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABS | acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene |

| BAAs | biologically active additives |

| CM | composite materials |

| CPhMI | carboxyphenylmaleimide |

| DTA | differential thermal analysis |

| TGA | thermogravimetric analysis |

| IR | Infrared Spectroscopy |

| UV | ultraviolet spectroscopy |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| P. aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| C. albicans | Candida albicans |

References

- Patravale, V.; Disouza, J.I.; Shahiwala, A. Polymers for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications: Fundamentals, Selection, and Preparation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 14–180. [Google Scholar]

- Haktaniyan, M.; Bradley, M. Polymers showing intrinsic antimicrobial activity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 8584–8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, V.; Thomas, R.; Martin, Z. Use of Polymeric or Oligomeric Active Ingredients for Medical Devices. Pat. RF 2 557 937C2, 27 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Georgescu, C.; Turcuş, V.; Olah, N.K.; Mathe, E. An overview of natural antimicrobials role in food. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dontsova, E.P.; Zharnenkova, O.A.; Snezhko, A.G.; Uzdensky, V.B. Polymer materials with antimicrobial properties. Plastic 2014, 131, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kovylin, R.S.; Aleynik, D.Y.; Fedushkin, I.L. Modern porous polymer implants: Synthesis, properties, and application. Polym. Sci. Ser. C 2021, 63, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, D.; González-Benito, J. Polymeric Materials with Antibacterial Activity: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; He, J.; Liu, F. Preparation and properties of antibacterial ABS plastics based on polymeric quaternary phosphonium salts antibacterial agents. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 2515–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasulzade, N.S.; Alikhanova, A.I.; Bakhshaliyeva, K.F.; Muradov, P.Z. Method for Obtaining Antibacterial Polymer Composite Material. Pat İ 2023 0057, 23 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yudin, V.V.; Kulikova, T.I.; Morozov, A.G.; Egorikhina, M.N.; Rubtsova, Y.P.; Charykova, I.N.; Linkova, D.D.; Zaslavskaya, M.I.; Farafontova, E.A.; Kovylin, R.S.; et al. Features of Changes in the Structure and Properties of a Porous Polymer Material with Antibacterial Activity during Biodegradation in an In Vitro Model. Polymers 2024, 16, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonova, O.M.; Panova, Y.A.; Akhmetov, I.G. Study of the effect of maleic anhydride on the synthesis, morphology, and properties of ABS plastic. Plast. Masses 2017, 45, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, F.; He, M. Synthesis of Functionalized Poly(N-(3-carboxyphenyl)maleimide-alt-styrene) and Its Heat-Resistance Mechanism. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2020, 62, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjos, E.G.R.; Marini, J.; Montagna, L.S.; Thaís Montanheiro, L.A.; Passador, F.R. Reactive processing of maleic anhydride-grafted ABS and its compatibilizing effect on PC/ABS blendsn. Polímeros 2020, 30, e2020039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambrallimath, V.; Keshavamurthy, R.; Saravanabavan, D.; Koppad, P.G.; Kumar, G.S.P. Thermal behavior of PC-ABS based graphene filled polymer nanocomposite synthesized by FDM process. Compos. Commun. 2019, 15, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakır, A.A.; Atik, R.; Özerinç, S. Mechanical properties of thermoplastic parts produced by fused deposition modeling: A review. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Thomas, D. Development of non-toxic antimicrobial additives for polymer surfaces. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2019, 30, 1321–1334. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.U.; Sailaja, R.R.N. Mechanical and Flammability Characteristics of PC/ABS Composites Loaded with Flyash Cenospheres and Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Polym. Compos. 2017, 38, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Lago, E.; Cagnin, E.; Boaretti, C.; Roso, M.; Lorenzetti, A.; Modesti, M. Influence of Different Carbon-Based Fillers on Electrical and Mechanical Properties of a PC/ABS Blend. Polymers 2020, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asyadi, F.; Jawaid, M.; Hassan, A.; Wahit, M.U. Mechanical Properties of Mica-Filled Polycarbonate/Poly(Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene) Composites. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2013, 52, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Zhao, G.; Hui, Y.; Guan, Y. Mechanical and thermal properties of ABS/PMMA/Potassium Titanate Whisker Composites. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2017, 56, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Shang, P.; Mao, Y.; Li, Q.; Wu, C. Preparation and characterization of ABS/anhydrous cobalt chloride composites. Mater. Res. Express. 2018, 5, 015309–015324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okolie, O.; Kumar, A.; Edwards, C.; Lawton, L.A.; Oke, A.; McDonald, S.; Thakur, V.K.; Njuguna, J. Bio-based sustainable polymers and materials: From processing to biodegradation. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Ramamoorthy, M. Mechanical characterization and experimental modal analysis of 3D Printed ABS, PC and PC-ABS materials. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulanda, K.; Oleksy, M.; Oliwa, R. Polymer Composites Based on Polycarbonate/Acrylonitrile-Butadiene-Styrene Used in Rapid Prototyping Technology. Polymers 2023, 15, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y. Maleimide-modified ABS composites: Thermal stability and structural behavior. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 176, 109146. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, H.G.; Mohamed, A.A.; Waheedullah, G.; Naheed, S.; Mohammad, A.; Mohammad, J.; Othman, Y.A. Flexural thermal and dynamic mechanical properties of date palm fibres reinforced epoxy composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R.; Butt, J.; Shirvani, H. Investigating the Properties of ABS-Based Plastic Composites Manufactured by Composite Plastic Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guliyeva, S.I.; Mammadov, B.A.; Garaev, E.A.; Alikhanova, A.I.; Rasulov, N.S. Method for Obtaining Antibacterial Composite Materials from Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS. Eurasian Patent No. 202591072/09/01, 22 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azazy, M. Infrared Spectroscopy—Principles, Advances, and Applications Introductory Chapter: Infrared Spectroscopy—A Synopsis of the Fundamentals and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 220. [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, H. Encyclopedia of Infrared Spectroscopy: Volume III (Polymers, Biopolymers and Minerals Technology); NY Research Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 334. [Google Scholar]

- El-Azazy, M.; Al-Saad, K.; El-Shafie, A.S. Infrared Spectroscopy—Perspectives and Applications; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023; Volume 220. [Google Scholar]

- Lagunin, A.; Stepanchikova, A.; Filimonov, D.; Poroikov, V. PASS: Prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 747–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, E.G.R.; Braga, N.F.; Ribeiro, B.; Escanio, C.A.; Cardoso, A.d.M.; Marini, J.; Antonelli, E.; Passador, F.R. Influence of blending protocol on the mechanical, rheological, and electromagnetic properties of PC/ABS/ABS-g-MAH blend-based MWCNT nanocomposites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 139, e51946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K. Polymer and Composite Rheology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; Volume 408. [Google Scholar]

- Assad, M.E.H.; Khosravi, A.; Hashemian, M. The Fundamentals of Thermal Analysis; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2023; Volume 242. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M. Thermal Analysis in Practice, Fundamental Aspects; Carl Hanser Verlag: München, Germany, 2018; Volume 349. [Google Scholar]

- Sitnikova, V.E.; Ponomareva, A.A.; Uspenskaya, M.V. Methods of Thermal Analysis: Practical; ITMO University: Saint-Petersburg, Russia, 2021; Volume 151. [Google Scholar]

- Guliyeva, S.I.; Alikhanova, A.I.; Garayev, E.A.; Mammadov, B.A.; Rasulov, N.S. Synthesis of carboxyphenymaleimides and study of their biological activity properties. Am. Sci. J. 2021, 52, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, P.R.; Rosenthal, K.S.; Pfaller, M.A. Medical Microbiology, 10th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; Volume 953. [Google Scholar]

| Samples | BAA in the Composition of CM | Relative Elongation % | Mechanical Strength MPa | Melt Flow Index (MFI) g/10 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM1 | o-CPhMI | 40 | 37.6 | 1.41 |

| CM2 | m-CPhMI | 40 | 37.7 | 1.45 |

| CM3 | p-CPhMI | 41 | 38.7 | 1.44 |

| CM4 | ABS without additives | 42 | 38.8 | 1.42 |

| Temperature, °C | CM | Dynamic Viscosity, mPa·s | Kinematic Viscosity, mm2/s | Density, g/cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | o-CPhMI/ABS | 1.8287 | 1.4321 | 1.2769 |

| m-CPhMI/ABS | 1.6193 | 1.2678 | 1.2773 | |

| p-CPhMI/ABS | 1.7974 | 1.4084 | 1.2762 | |

| 25 | o-CPhMI/ABS | 1.5520 | 1.2291 | 1.2627 |

| m-CPhMI/ABS | 1.3740 | 1.0881 | 1.2627 | |

| p-CPhMI/ABS | 1.4455 | 1.1458 | 1.2616 | |

| 35 | o-CPhMI/ABS | 1.2981 | 1.0403 | 1.2479 |

| m-CPhMI/ABS | 1.1651 | 0.93346 | 1.2481 | |

| p-CPhMI/ABS | 1.2464 | 0.99966 | 1.2468 | |

| 45 | o-CPhMI/ABS | 1.1152 | 0.90448 | 1.2330 |

| m-CPhMI/ABS | 1.0471 | 0.84889 | 1.2335 | |

| p-CPhMI/ABS | 1.1181 | 0.90758 | 1.2320 |

| Composition of the Composites (Mass %) | Ea, kJ·mol−1 | Mass Loss, % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature, °C | ||||||||||

| 300 | 325 | 350 | 375 | 400 | 420 | 440 | 450 | 475 | ||

| o-CPhMI/ABS | 179 | 0 | 2 | 19 | 20.1 | 25 | 74.5 | 75.5 | 86.8 | 87 |

| m-CPhMI/ABS | 125 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7.8 | 27 | 82 | 84 | 95.5 |

| p-CPhMI/ABS | 112.2 | 0 | 1 | 1.5 | 6 | 10 | 26 | 75 | 79 | 99.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Garaev, E.; Guliyeva, S.; Alikhanova, A.; Huseynguliyeva, K.; Mammadov, B. Obtaining and Studying the Properties of Composite Materials from ortho-, meta-, para-Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS. Molecules 2026, 31, 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010190

Garaev E, Guliyeva S, Alikhanova A, Huseynguliyeva K, Mammadov B. Obtaining and Studying the Properties of Composite Materials from ortho-, meta-, para-Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):190. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010190

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaraev, Eldar, Shahana Guliyeva, Aygun Alikhanova, Konul Huseynguliyeva, and Bakhtiyar Mammadov. 2026. "Obtaining and Studying the Properties of Composite Materials from ortho-, meta-, para-Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS" Molecules 31, no. 1: 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010190

APA StyleGaraev, E., Guliyeva, S., Alikhanova, A., Huseynguliyeva, K., & Mammadov, B. (2026). Obtaining and Studying the Properties of Composite Materials from ortho-, meta-, para-Carboxyphenylmaleimide and ABS. Molecules, 31(1), 190. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010190