Influence of Coexisting Copper and Zinc on the Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils: A Simulation Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Effects of Different Cu and Zn Concentrations on the Isothermal Adsorption of SDZ

2.2. Tracer Br− Migration in the Soil Column

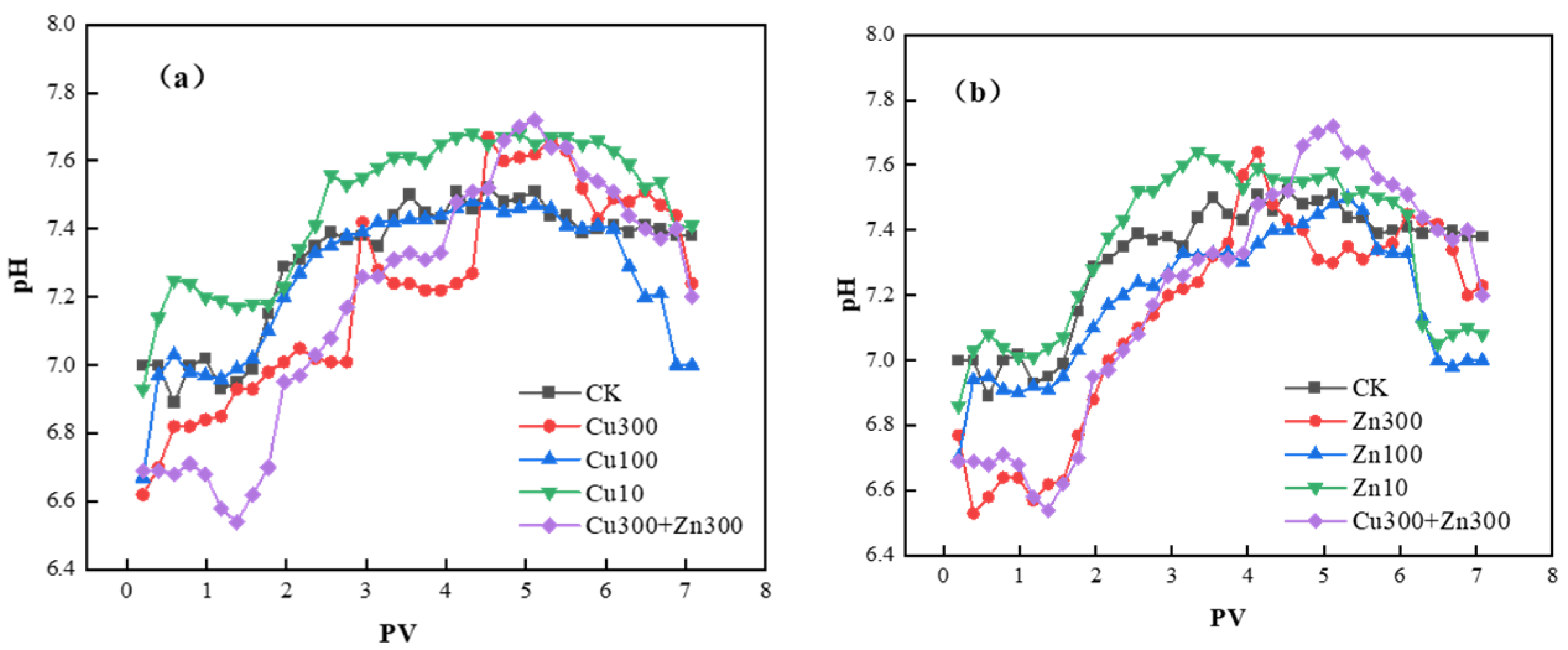

2.3. SDZ Migration Characteristics Under Different Cu and Zn Concentrations

2.4. Changes in SDZ Breakthrough Curve Parameters Under Different Cu and Zn Concentrations

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Reagents

3.2. Soil Sample Collection and Preparation

3.3. Batch Equilibrium Adsorption Experiment

3.4. Soil Column Experiment

3.4.1. Br− Tracer

3.4.2. SDZ Migration Experiment

3.4.3. Solute Transport Model

3.5. Data Processing

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaballah, M.S.; Guo, J.; Sun, H.; Aboagye, D.; Sobhi, M.; Muhmood, A.; Dong, R. A review targeting veterinary antibiotics removal from livestock manure management systems and future outlook. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 333, 125069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gros, M.; Marti, E.; Balcázar, J.L.; Boy-Roura, M.; Busquets, A.; Colón, J.; Sànchez-Melsió, A.; Lekunberri, I.; Borrego, C.M.; Ponsá, S.; et al. Fate of pharmaceuticals and antibiotic resistance genes in a full-scale on-farm livestock waste treatment plant. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 378, 120716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.-T.; Zhai, Y.-Q.; Cai, Y.-Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Ying, G.-G. Hypothetical scenarios estimating and simulating the fate of antibiotics: Implications for antibiotic environmental pollution caused by farmyard manure application. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Ying, G.G.; Pan, C.G.; Liu, Y.S.; Zhao, J.L. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China: Source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 6772–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu, V.; Gimeno-García, E.; Pascual, J.; Vazquez-Roig, P.; Picó, Y. Presence of pharmaceuticals and heavy metals in the waters of a Mediterranean coastal wetland: Potential interactions and the influence of the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 540, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Pollution; Study Data from University of Jinan Update Knowledge of Environmental Pollution (The presence of tetracyclines and sulfonamides in swine feeds and feces: Dependence on the antibiotic type and swine growth stages). Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2020, 1536.

- Ovung, A.; Bhattacharyya, J. Sulfonamide drugs: Structure, antibacterial property, toxicity, and biophysical interactions. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.L.; Liu, L.C.; Chen, W.R. Adsorption of sulfamethoxazole and sulfapyridine antibiotics in high organic content soils. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Shen, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Wang, H.; Koelmans, A.; Cornelissen, G.; Tao, S.; Wang, X. Sorption mechanisms of sulfamethazine to soil humin and its subfractions after sequential treatments. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 221, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, W.; Huang, Y. Biotransformation of enrofloxacin-copper combined pollutant in aqueous environments by fungus Cladosporium cladosporioides (CGMCC 40504). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Yang, C.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Dang, Z.; Huang, W. Complexation of sulfamethazine with Cd(II) and Pb(II): Implication for co-adsorption of SMT and Cd(II) on goethite. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 11576–11583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-L.; Lin, M.; Wei, L.; Yi-Fan, C.; Qi-Yang, T.; Qiao-Hong, Z.; Zhen-Bin, W.; Feng, H. Purification Performance of Rural Livestock and Poultry Breeding Tail Water by Constructed Wetland Under Cu and SMZ Combined Pollution. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2022, 46, 1484–1493+1592. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Lu, H. Distribution of Sulfonamide Antibiotics and Resistance Genes and Their Correlation with Water Quality in Urban Rivers (Changchun City, China) in Autumn and Winter. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Wei, S.; Sun, R.; Zou, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, R.; Huang, L. The Forms, Distribution, and Risk Assessment of Sulfonamide Antibiotics in the Manure-Soil-Vegetable System of Feedlot Livestock. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2020, 105, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hao, W.; Liu, S.; Ren, S.; Min, J.; Zou, C. Distribution patterns of antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese vegetable farmlands and key soil physicochemical factors. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2026, 14, 120705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Meng, X.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y.; Shen, Z. New insights into the distribution and risk of antibiotics: From point to non-point source in a rapidly urbanizing watershed—A case study of the Wenyu River, Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 534, 147085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Gao, H.; Li, R.; Jia, X.; Yao, W.; Yao, Z. Characteristics of regionalized distribution of antibiotics and ARGs in Daliao River-Liaodong Bay waters and their environmental impact factors. J. Environ. Sci. 2026, 160, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jian, M.; Che, Y.; Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tan, C.; Li, H. Migration of naphthalene in a biochar-amended bioretention facility based on HYDRUS-1D analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 369, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, Y.; Chen, L. Modeling the effects of parameter optimization on three bioretention tanks using the HYDRUS-1D model. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 217, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liu, B.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Rene, E.R.; Ma, W. Simulation and prediction of sulfamethazine migration, transformation and risk diffusion during cross-media infiltration from surface water to groundwater driven by dynamic water level: Machine learning coupled HYDRUS-GMS model. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Song, S.; Li, F.; Cui, H.; Wang, R.; Yang, S.; Li, Z.; Chen, G. Multimedia fate of sulfamethoxazole (SMX) in a water-scarce city by coupling fugacity model and HYDRUS-1D model. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, O.; Shijie, Z.; Xinyu, L.; Yang, H.; Shuaifan, R. Effects of Biochar on Sorption and Transport of Florfenicol in Purple Soil. Res. Environ. Sci. 2022, 35, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Tactical study on the ecological protection of the western Songnen Plain. SSCSA 2003, 19, 282–285+289. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, M.A.; Abbas, M.S.; Mustaqeem, M.; Bashir, M.; Shabbir, A.; Saeed, M.T.; Irfan, R.M. Comprehensive assessment of heavy metal contamination in soil-plant systems and health risks from wastewater-irrigated vegetables. Colloids Surf. C Environ. Asp. 2024, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Dai, Q.; Hu, J.; Wu, H.; Chen, J. Profiles of tetracycline resistance genes in paddy soils with three different organic fertilizer applications. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 306, 119368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J. Adsorption Behavior of Sulfadiazine and Copper in Soil and Its Influencing Factors. Master’s Thesis, Jiangsu University of Science and Technology, Zhenjiang, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.D.; Lin, Q.; Xu, S.H. Effects of Cd/Cu/Pb on Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soil. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2018, 55, 1120–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Xia, S.; Zhao, J. Struvite-supported biochar composite effectively lowers Cu bio-availability and the abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes in soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Cai, B.; Liu, R.; Xu, W.; Jin, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q.; Yong, Q. Synergistic and antagonistic adsorption mechanisms of copper(II) and cefazolin onto bio-based chitosan/humic composite: A combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahervand, S.; Jalali, M. Sorption and desorption of potentially toxic metals (Cd, Cu, Ni and Zn) by soil amended with bentonite, calcite and zeolite as a function of pH. J. Geochem. Explor. 2017, 181, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Hao, Q.; Qian, X.; Yan, G.; Gu, J.; Sun, W. Normal levels of Cu and Zn contamination present in swine manure increase the antibiotic resistance gene abundances in composting products. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 194, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, S.; Zhao, J. Biochar reversed antibiotic resistance genes spread in biodegradable microplastics and Cu co-contaminated soil by lowering Cu bio-availability and regulating denitrification process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, S. Insights into the pH-dependent interactions of sulfadiazine antibiotic with soil particle models. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 917, 170537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yu, W.; Ma, Q.; Zhou, H. Interactive effects of sulfadiazine and Cu(II) on their sorption and desorption on two soils with different characteristics. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doretto, K.M.; Rath, S. Sorption of sulfadiazine on Brazilian soils. Chemosphere 2013, 90, 2027–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conde-Cid, M.; Nóvoa-Muñoz, J.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E.; Arias-Estévez, M. Pedotransfer functions to estimate the adsorption and desorption of sulfadiazine in agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 691, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cela-Dablanca, R.; Barreiro-Buján, A.; Ferreira-Coelho, G.; López, L.R.; Santás-Miguel, V.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, E. Competitive adsorption and desorption of tetracycline and sulfadiazine in crop soils. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurwadkar, S.T.; Adams, C.D.; Meyer, M.T.; Kolpin, D.W. Comparative mobility of sulfonamides and bromide tracer in three soils. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertpaitoonpan, W.; Ong, S.K.; Moorman, T.B. Effect of organic carbon and pH on soil sorption of sulfamethazine. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Sarmah, A.K. Assessing the sorption and leaching behaviour of three sulfonamides in pasture soils through batch and column studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 493, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Han, Y.; Jing, M.; Chen, J. Sorption and transport of sulfonamides in soils amended with wheat straw-derived biochar: Effects of water pH, coexistence copper ion, and dissolved organic matter. J. Soils Sediments 2017, 17, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Hu, S.; Rong, F.; Gao, X.; Chao, L.; Liu, A. Effects of copper on the adsorption—Desorption characteristics of sulfadiazine in soil at different calcium ion concentrations. Environ. Pollut. Control 2023, 45, 602–607+613. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, K.; Yang, R. Binary Adsorption and Migration Simulation of Levofloxacin with zinc at Concentrations Simulating Wastewater on Silty Clay and The Potential Environmental Risk in Groundwater. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H. Adsorption behavior of antibiotic in soil environment: A critical review. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2015, 9, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdiales, C.; Urdiales-Flores, D.; Tapia, Y.; Caceres-Jensen, L.; Šimůnek, J.; Antilén, M. Transport mechanisms of the anthropogenic contaminant sulfamethoxazole in volcanic ash soils at equilibrium pH evaluated using the HYDRUS-1D model. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 487, 137077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdi, S.; Mosbahi, M.; Issaoui, M.; Barreiro, A.; Cela-Dablanca, R.; Brahmi, J.; Tlili, A.; Jamoussi, F.; Fernández-Sanjurjo, M.J.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; et al. Experimental data and modeling of sulfadiazine adsorption onto raw and modified clays from Tunisia. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 118309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, M.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, D.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, G.; Wang, J. Synthesis and reactivity of oxygen chelated ruthenium carbene metathesis catalysts. J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 756, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experimental Treatment | Freundlich Equation | Langmuir Equation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kf | 1/n | R2 | KL | qmax | R2 | |

| CK | 0.181 | 0.952 | 0.980 | 0.004 | 40.978 | 0.955 |

| Cu10 | 0.156 | 1.015 | 0.980 | NA | NA | NA |

| Cu100 | 0.253 | 0.887 | 0.984 | 0.008 | 26.138 | 0.972 |

| Cu300 | 0.168 | 0.902 | 0.990 | 0.044 | 7.041 | 0.944 |

| Zn10 | 0.232 | 0.916 | 0.987 | 0.006 | 32.901 | 0.972 |

| Zn100 | 0.276 | 0.851 | 0.995 | 0.010 | 20.870 | 0.990 |

| Zn300 | 0.206 | 0.904 | 0.977 | 0.007 | 24.197 | 0.948 |

| Cu300 + Zn300 | 0.175 | 0.863 | 0.922 | 0.010 | 13.167 | 0.820 |

| Parameters | v (cm h−1) | λ (cm) | D (cm2/h) | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil column | 4.370 | 0.176 | 0.770 | 0.900 | 0.039 |

| Experimental Treatment | f | Kd | α | R2 | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0.292 | 0.318 | 0.001 | 0.996 | 0.033 |

| Cu10 | 0.217 | 0.645 | 0.006 | 0.977 | 0.029 |

| Cu100 | 0.175 | 0.397 | 0.005 | 0.915 | 0.062 |

| Cu300 | 0.554 | 0.285 | 0.003 | 0.970 | 0.032 |

| Zn10 | 0.101 | 0.373 | 0.001 | 0.979 | 0.027 |

| Zn100 | 0.267 | 0.213 | 0.002 | 0.973 | 0.025 |

| Zn300 | 0.553 | 0.230 | 0.002 | 0.986 | 0.024 |

| Cu300 + Zn300 | 0.292 | 0.205 | 0.027 | 0.963 | 0.038 |

| Parameters | Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils |

|---|---|

| pH | 7.85 ± 0.10 |

| EC (μS cm−1) | 172.10 ± 0.77 |

| Content of Soluble Salts (g kg−1) | 1.10 ± 0.10 |

| CEC (cmol kg−1) | 4.54 ± 0.40 |

| OC (g kg−1) | 7.20 ± 0.08 |

| DOC (mg kg−1) | 95.02 ± 2.87 |

| clay proportion (%) | 2.83 ± 0.10 |

| silt proportion (%) | 45.61 ± 0.20 |

| sand proportion (%) | 51.56 ± 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, W.; Wu, X.; Shao, W.; Luo, N.; Zhou, J. Influence of Coexisting Copper and Zinc on the Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils: A Simulation Approach. Molecules 2026, 31, 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010189

Yang W, Wu X, Shao W, Luo N, Zhou J. Influence of Coexisting Copper and Zinc on the Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils: A Simulation Approach. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):189. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010189

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Wencong, Xia Wu, Wenyue Shao, Nana Luo, and Jia Zhou. 2026. "Influence of Coexisting Copper and Zinc on the Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils: A Simulation Approach" Molecules 31, no. 1: 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010189

APA StyleYang, W., Wu, X., Shao, W., Luo, N., & Zhou, J. (2026). Influence of Coexisting Copper and Zinc on the Adsorption and Migration of Sulfadiazine in Soda Saline–Alkali Wetland Soils: A Simulation Approach. Molecules, 31(1), 189. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010189