Optimizing Wine Production from Hybrid Cultivars: Impact of Grape Maceration Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Basic Oenological Parameters of Must and Wines

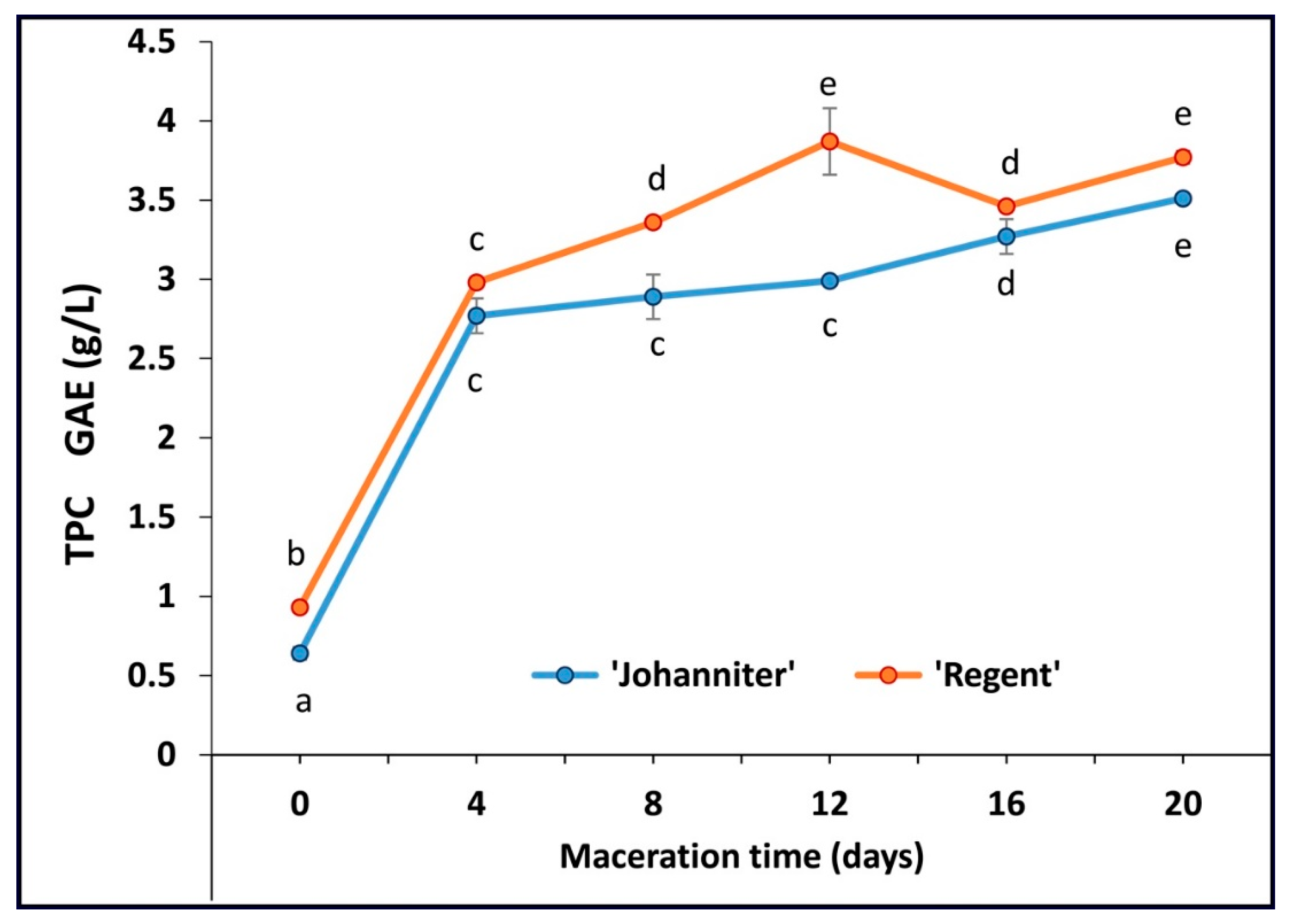

2.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

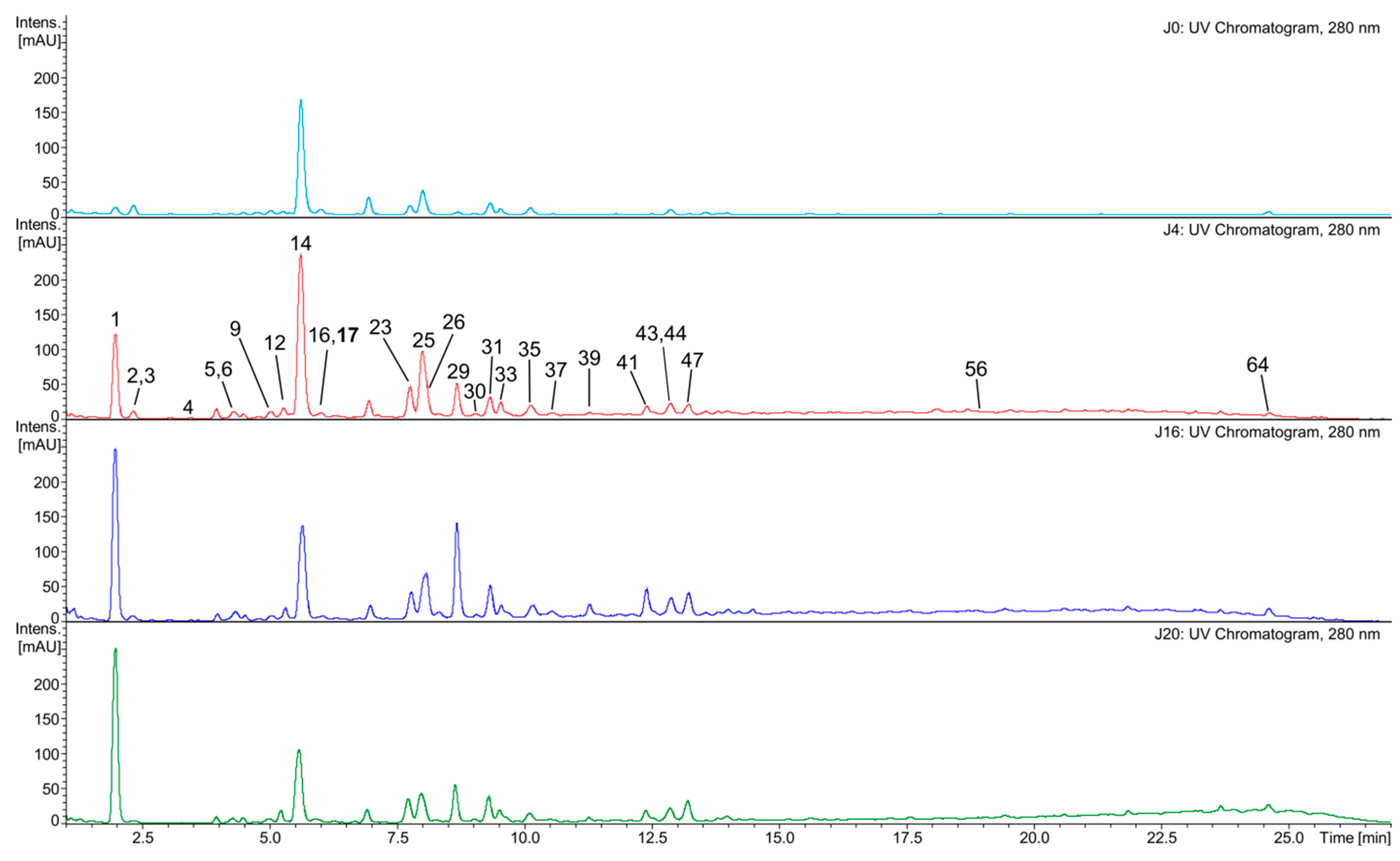

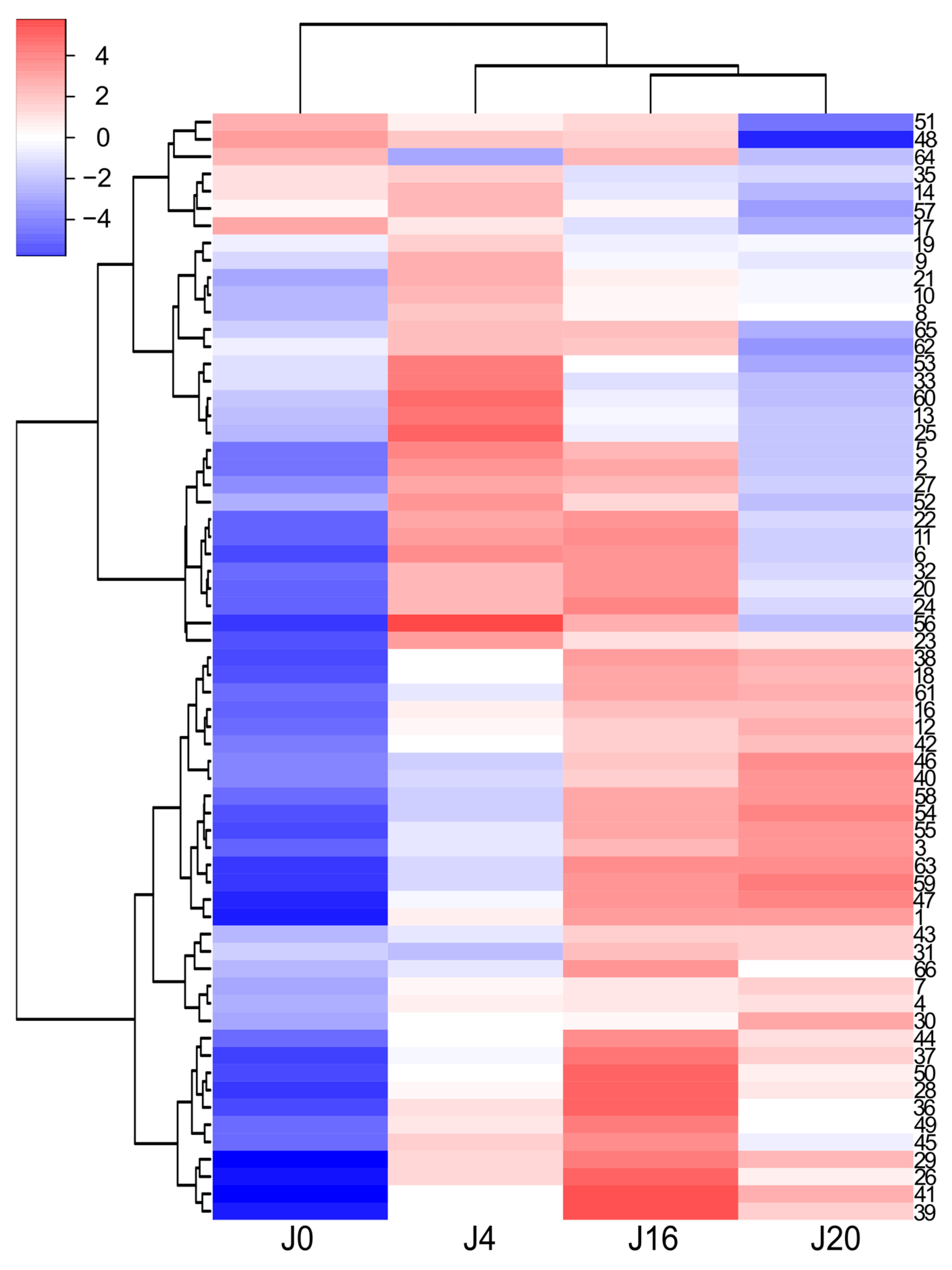

2.3. Composition of the White Wine Samples

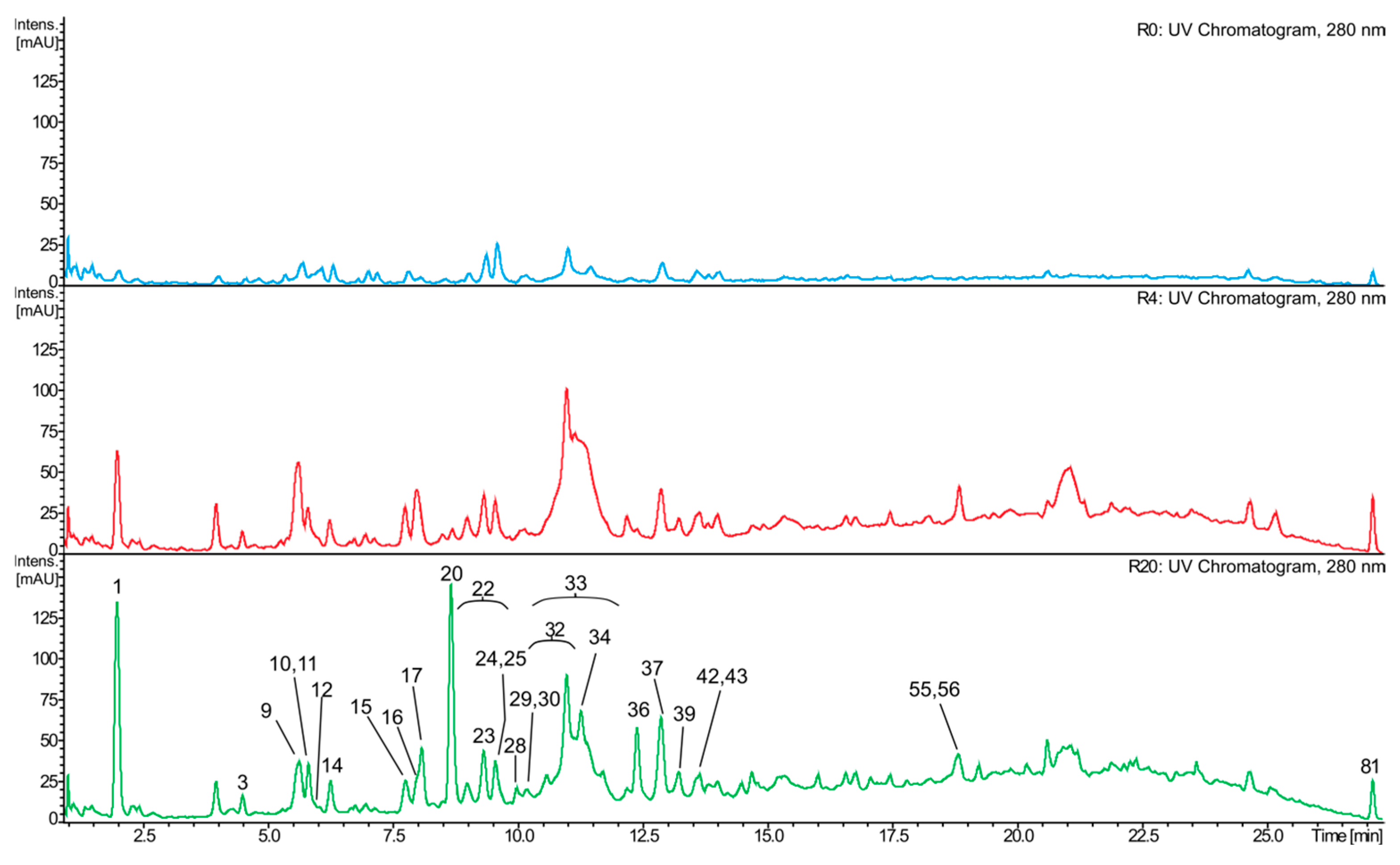

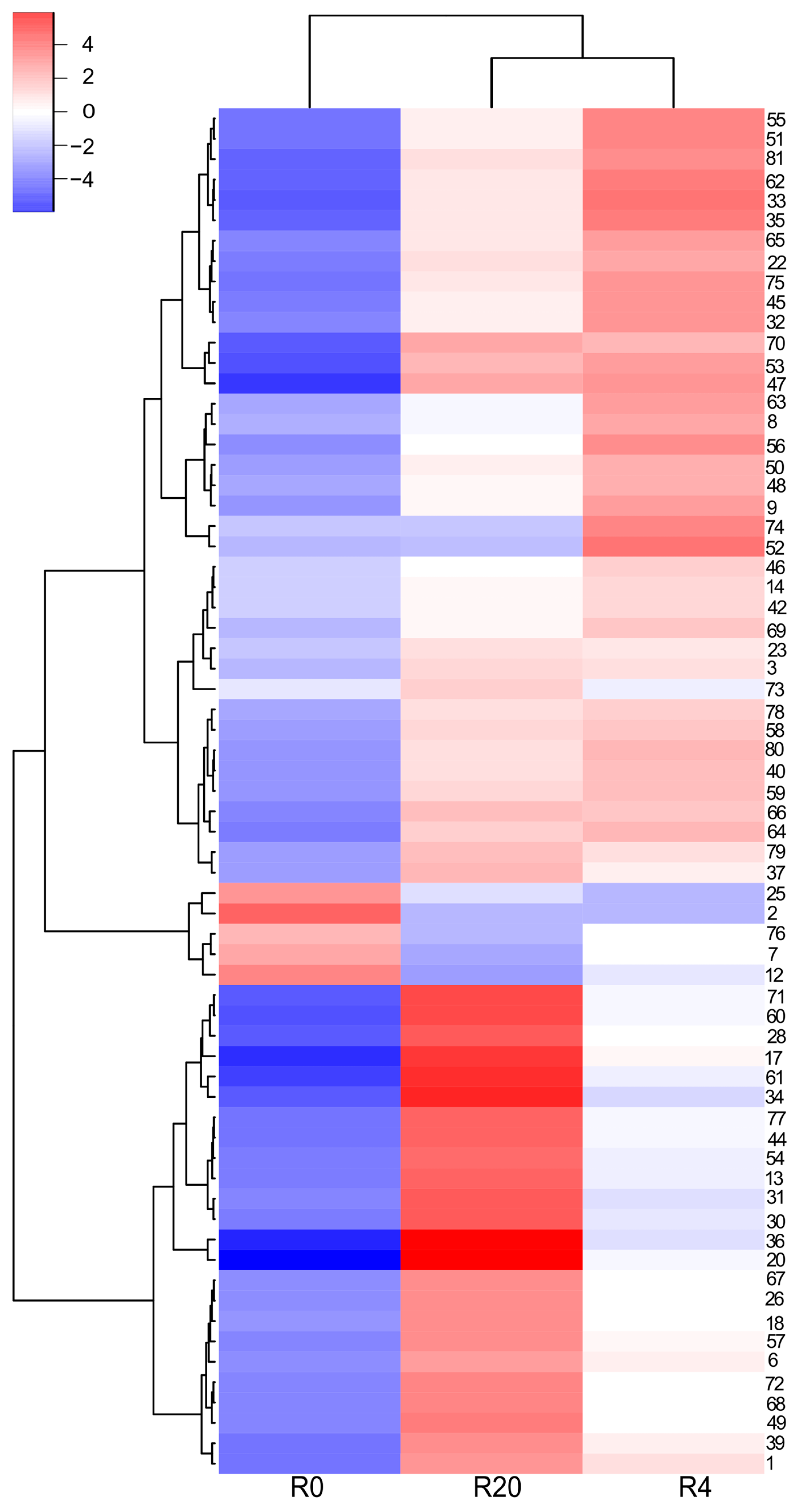

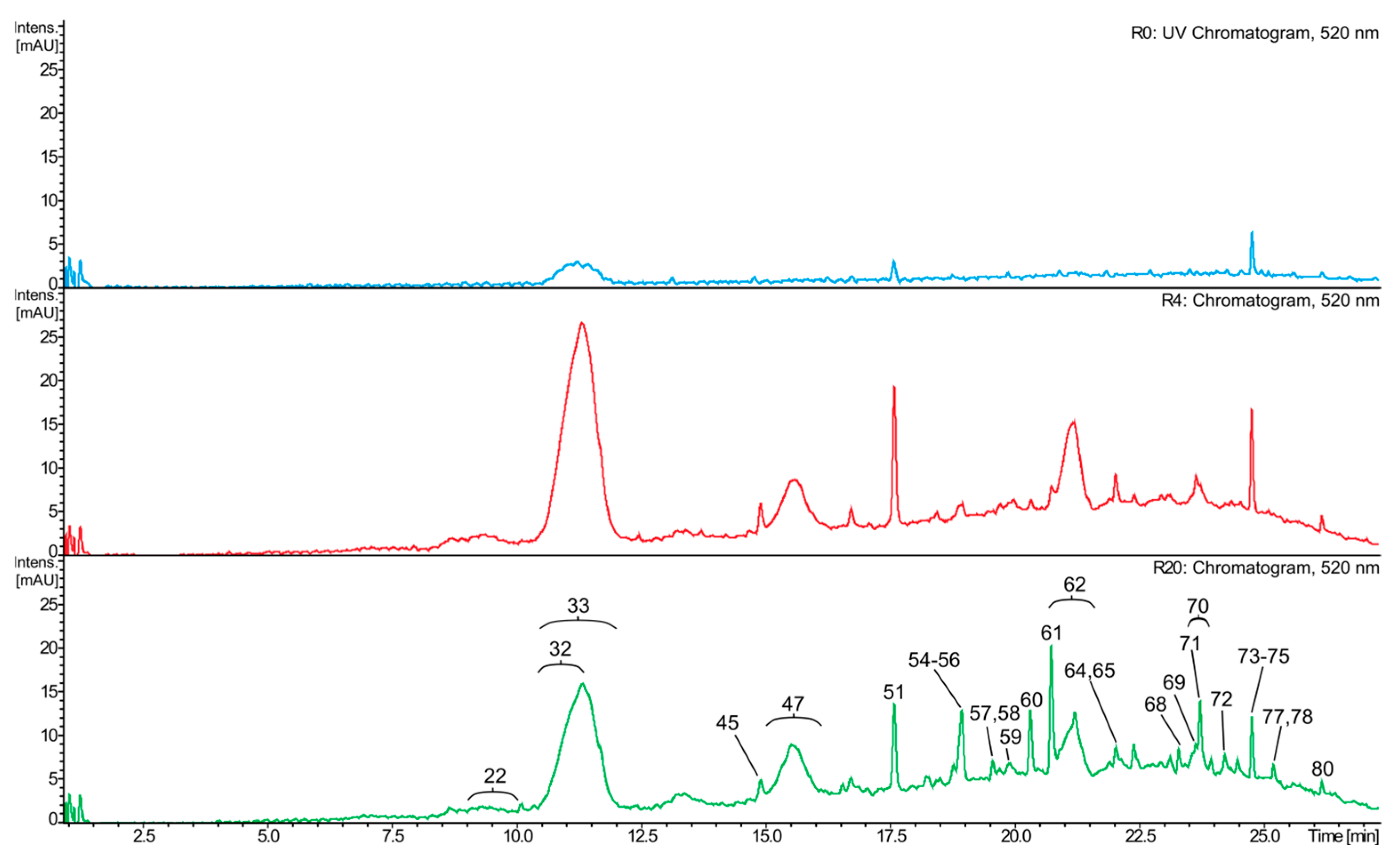

2.4. Composition of the Red Wine Samples

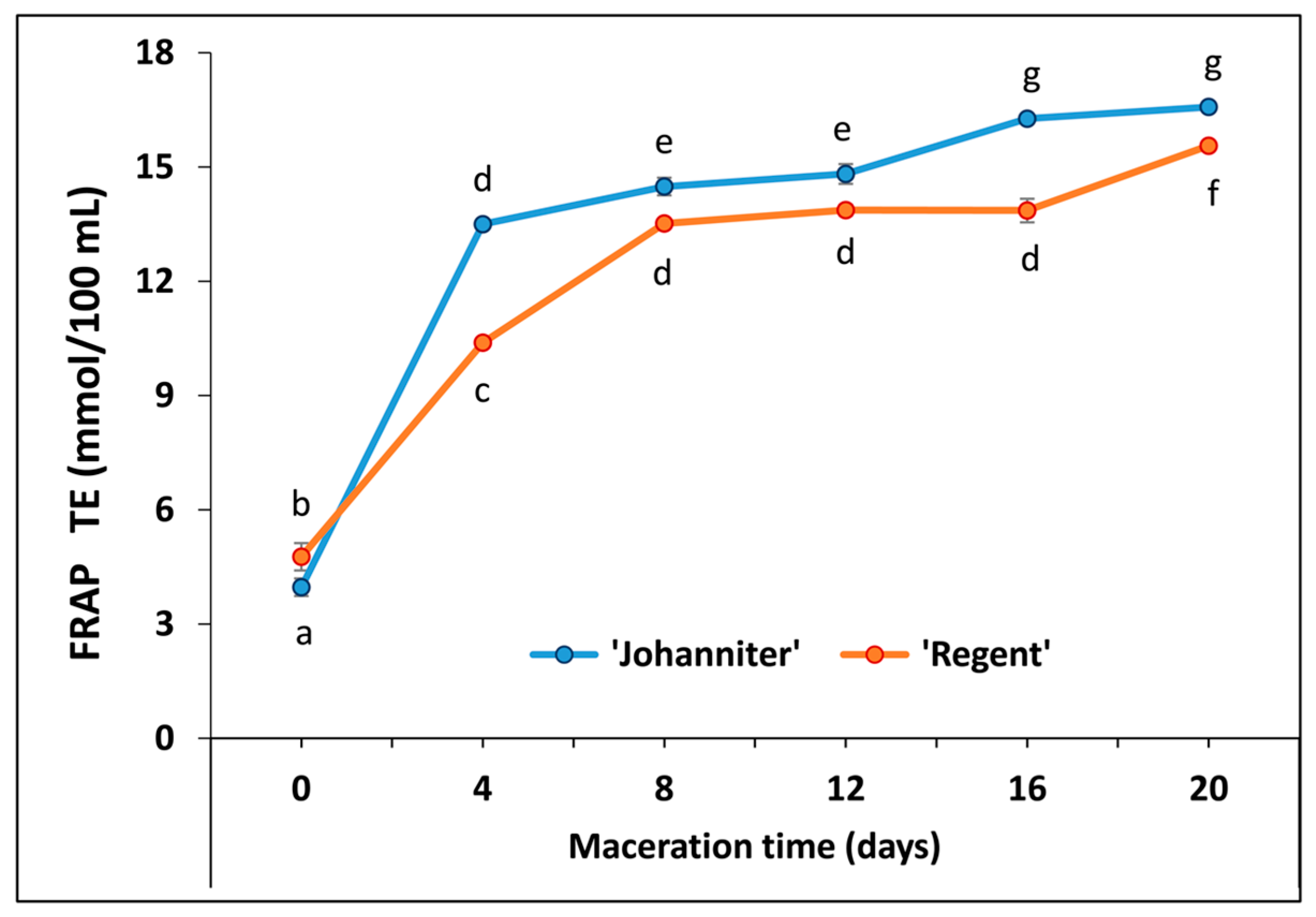

2.5. Antioxidant Capacity (FRAP)

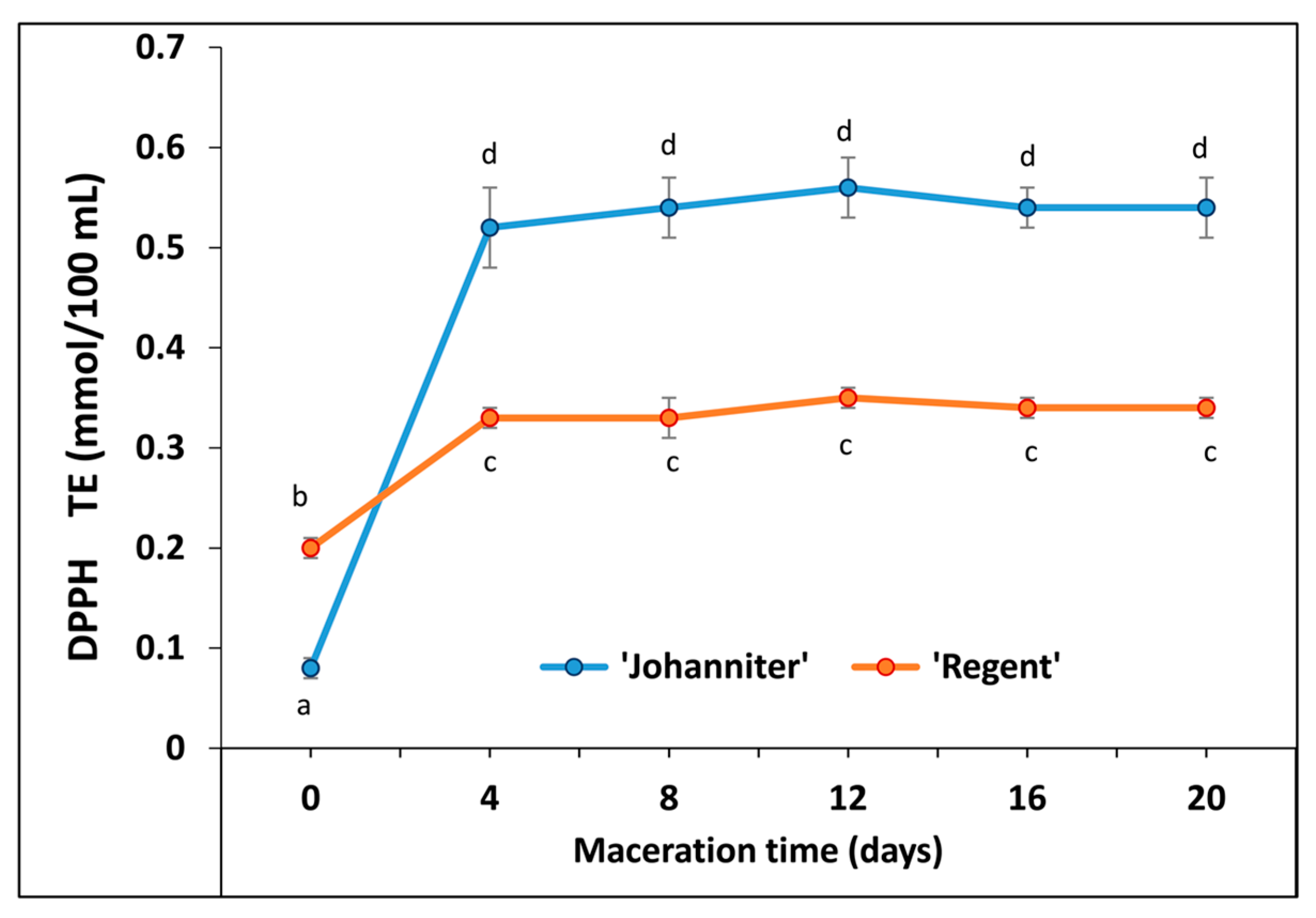

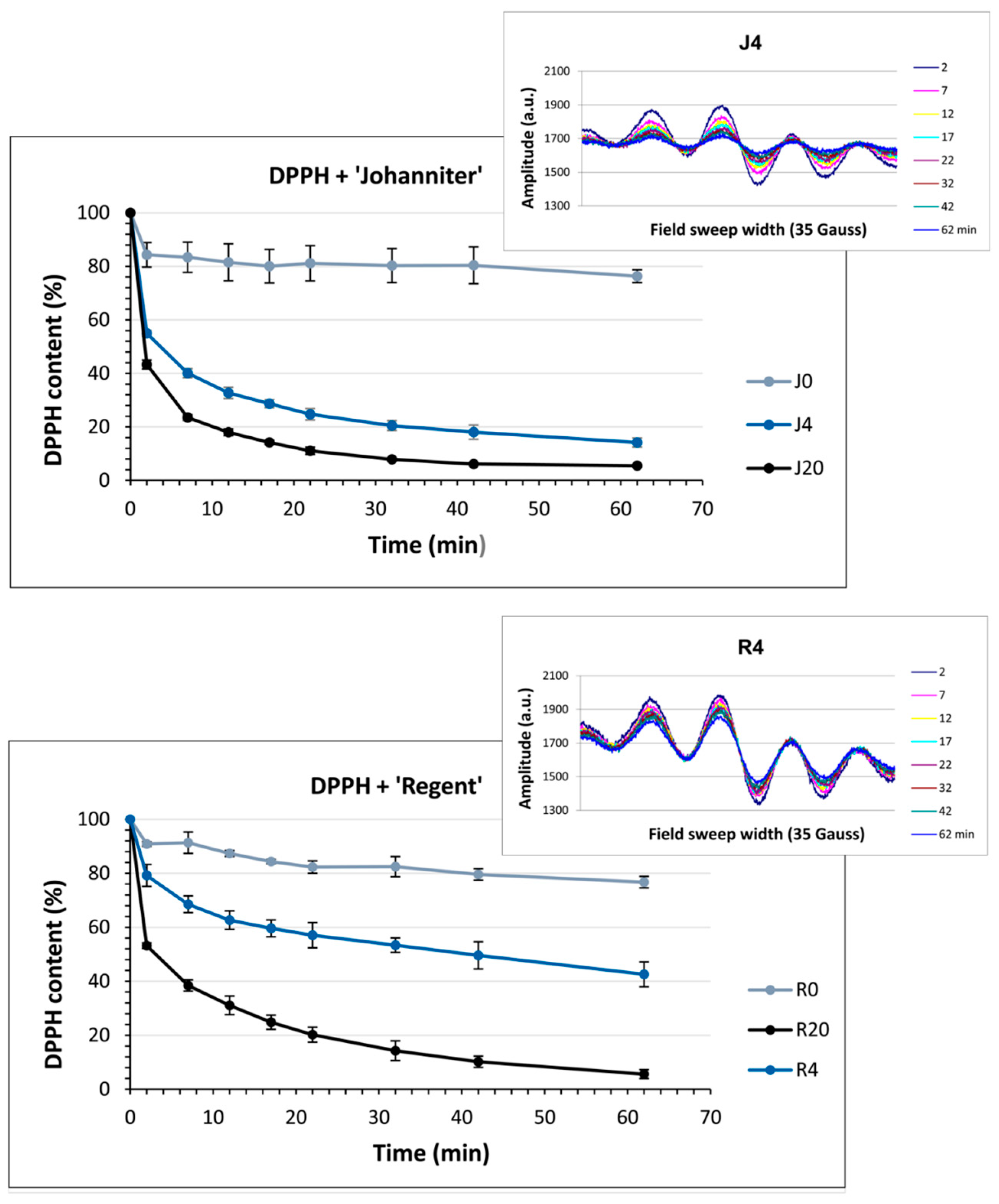

2.6. Antiradical Capacity (DPPH, Colorimetric Test)

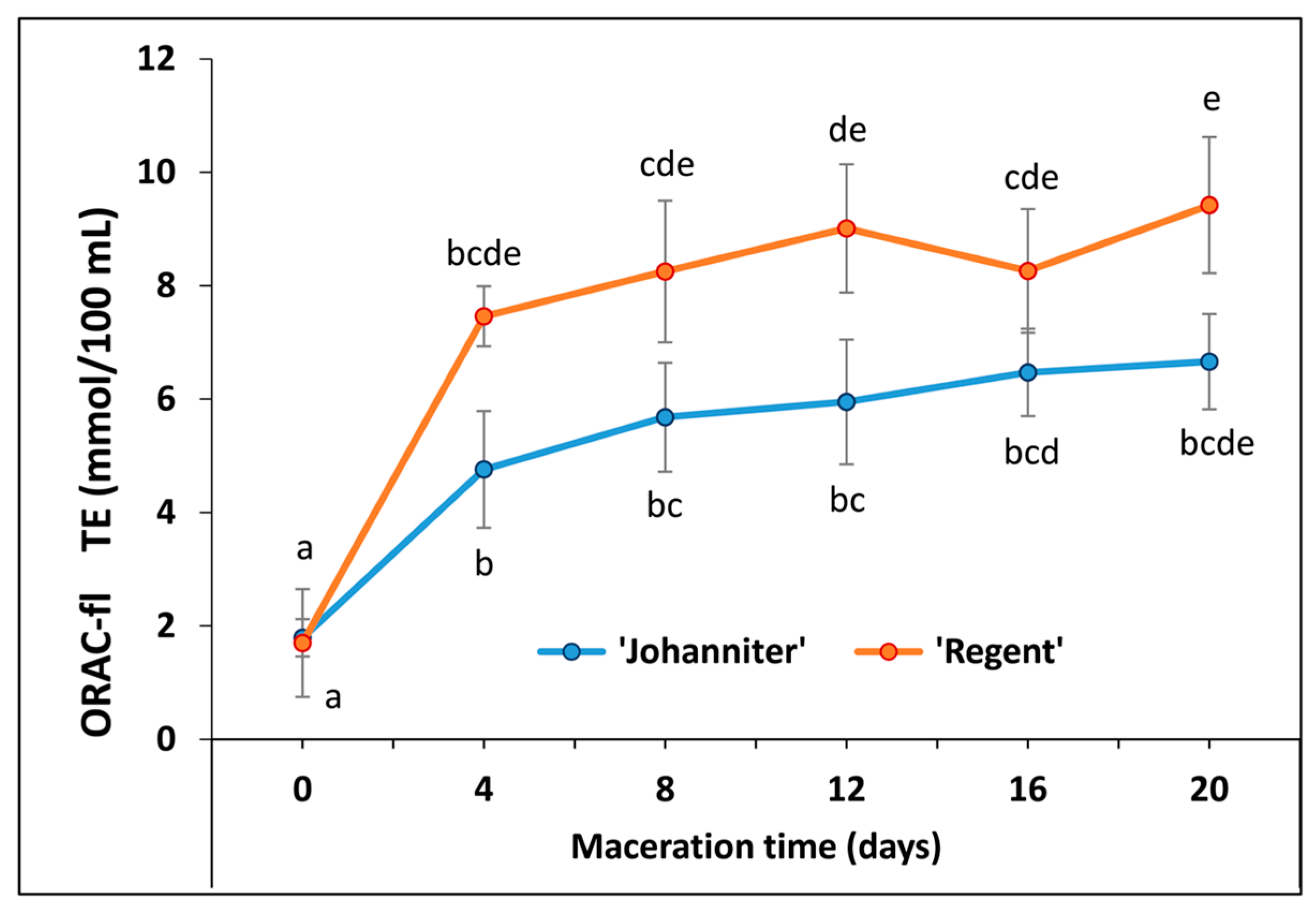

2.7. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC-Fl)

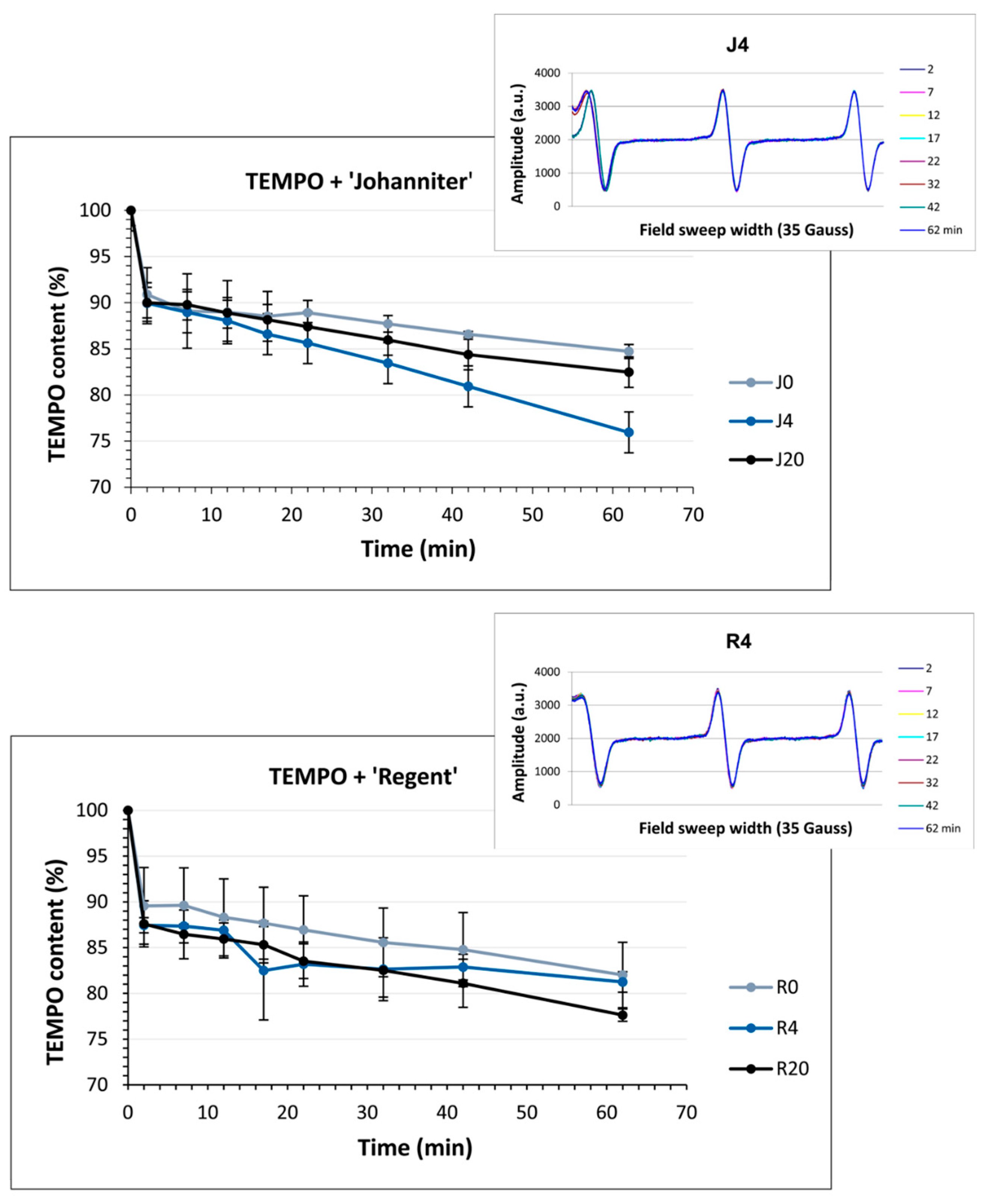

2.8. Antiradical Capacity Measured with EPR

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Hybrid Grapes

4.2. Chemicals and Reagents

4.3. Preparation of ‘Johanniter’ Wine for Testing

4.4. Preparation of ‘Regent’ Wine for Testing

4.5. Analytical Methods

4.5.1. Basic Oenological Characteristics of Must and Wine

Extract Content of Must

pH of Must and Wine

Total Acidity of Must

Total Acidity of Wine

Alcohol Content in Wine

Residual Sugar Content in Wine

Free Sulfur Dioxide Concentration in Wine

Total Sulfur Dioxide Concentration in Wine

L-Malic Acid Content in Wine

Tartaric Acid Content in Wine

4.5.2. Total Phenolic Content in Wine

4.5.3. Phenolic Profiling of Wine with UHPLC–MS

4.5.4. Antioxidant Capacity of Wine

4.5.5. DPPH Antiradical Capacity of Wine

4.5.6. Peroxyl Antiradical Capacity of Wine

4.5.7. Nitroxyl and Hydrazyl Antiradical Capacity of Wine

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAPH | 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) |

| BDE | bond dissociation energy/enthalpy |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DTNB | 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) |

| ET | electron transfer |

| EPR | Electron Paramagnetic Resonance |

| F6P | fructose-6-phosphate |

| FRAP | Ferric ion Reduction Antioxidant Power |

| G6P | glucose-6-phosphate |

| GAE | gallic acid equivalent |

| HAT | hydrogen atom transfer |

| J0,4… | ‘Johanniter’ wines obtained after appropriate maceration time, in days |

| KHT | potassium hydrogen tartrate |

| MLF | malolactic fermentation |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LC–MS | Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| ORAC-fl | fluorescein-based Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity |

| PCET | proton-coupled electron transfer |

| PT | proton transfer |

| PhO– | phenolate ion |

| R0,4… | ‘Regent’ wines obtained after appropriate maceration time, in days |

| ROO• | peroxyl radical |

| RT | room temperature |

| SET | single electron transfer |

| SPLET | sequential proton loss electron transfer |

| TAE | tartaric acid equivalent |

| TAm | total acidity of must |

| TAw | total acidity of wine |

| TE | Trolox equivalent |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl |

| TPC | total phenolic content |

| UHPLC | Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

References

- El Rayess, Y.; Nehme, N.; Azzi-Achkouty, S.; Julien, S.G. Wine Phenolic Compounds: Chemistry, Functionality and Health Benefits. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Beneficial Effects of Red Wine Polyphenols on Human Health: Comprehensive Review. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 782–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ćorković, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. A comprehensive review on polyphenols of white wine: Impact on wine quality and potential health benefits. Molecules 2024, 29, 5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrelia, S.; Di Renzo, L.; Bavaresco, L.; Bernardi, E.; Malaguti, M.; Giacosa, A. Moderate Wine Consumption and Health: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejarano, R.; Luján-Corro, M. Red Wine and Health: Approaches to Improve the Phenolic Content During Winemaking. Front. Nutr. 2022, 25, 890066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A. Should we remove wine from the Mediterranean diet?: A narrative review. Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo-Bastante, M.J.; Hermosín-Gutiérrez, I.; Pérez-Coello, M.S. Micro-oxygenation and oak chip treatments of red wines: Effects on colour-related phenolics, volatile composition and sensory characteristics. Part II: Merlot wines. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casassa, L.F.; Harbertson, J.F. Extraction, evolution, and sensory impact of phenolic compounds during red wine maceration. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine polyphenol content and its influence on wine quality and properties: A review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrowolska-Iwanek, J.; Gąstoł, M.; Wanat, A.; Krośniak, M.; Jancik, M.; Zagrodzki, P. Wine of cool-climate areas in South Poland. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buican, B.-C.; Colibaba, L.C.; Luchian, C.E.; Kallithraka, S.; Cotea, V.V. “Orange” wine—The resurgence of an ancient winemaking technique: A review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budziak-Wieczorek, I.; Mašán, V.; Rząd, K.; Gładyszewska, B.; Karcz, D.; Burg, P.; Čížková, A.; Gagoś, M.; Matwijczuk, A. Evaluation of the Quality of Selected White and Red Wines Produced from Moravia Region of Czech Republic Using Physicochemical Analysis, FTIR Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometric Techniques. Molecules 2023, 28, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribéreau-Gayon, P.; Glories, Y.; Maujean, A.; Dubourdieu, D. Handbook of Enology, Volume 2: The Chemistry of Wine, Stabilization and Treatments; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Míguez, M.; González-Miret, M.L.; Hernanz, D.; Fernández, M.Á.; Vicario, I.M.; Heredia, F.J. Effects of prefermentative skin contact conditions on colour and phenolic content of white wines. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, R.B.; Singleton, V.L.; Bisson, L.F.; Kunkee, R.E. Chapter 9: The Physical and Chemical Stability of Wine. In Principles and Practices of Winemaking; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 320–351. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Wine Research Institute, Urrbrae, Southern Australia. Available online: https://www.awri.com.au/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Watanabe-Saito, F.; Suzudo, A.; Hisamoto, M.; Okuda, T. Assessment of Sour Taste Quality and Its Relationship with Chemical Parameters in White Wine: A Case of Koshu Wine. Beverages 2025, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontoin, H.; Saucier, C.; Teissedre, P.-L.; Glories, Y. Effect of pH, ethanol and acidity on astringency and bitterness of grape seed tannin oligomers in model wine solution. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes Ferreira, A.; Mendes-Faia, A. The Role of Yeasts and Lactic Acid Bacteria on the Metabolism of Organic Acids during Winemaking. Foods 2020, 9, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, I.; Słowik, M.; Sroka, P.; Makarewicz, M. Effect of Oenococcus Oeni on parameters of oenological Polish wines. Food Sci. Technol. Qual. 2014, 3, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, I.; Cebulak, T.; Oszmiański, J. Characterization of Polish wines produced from the interspecific hybrid grapes grown in south-east Poland. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojton, N. Analiza Składu Win Wyprodukowanych z Różnych Odmian Winorosli z Terenu Małopolski. Master’s Thesis, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland, 2017. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Bednarska, S.; Dabrowa, A.; Kisala, J.; Kasprzyk, I. Antioxidant properties and resveratrol content of Polish Regent wines from Podkarpacie region. Czech J. Food Sci. 2019, 37, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socha, R.; Gałkowska, D.; Robak, J.; Fortuna, T.; Buksa, K. Characterization of Polish wines produced from the multispecies hybrid and Vitis vinifera L. grapes. Int. J. Food Prop. 2015, 18, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stój, A.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Domagala, D. Gentisic acid, salicylic acid, total phenolic content and cholinesterase inhibitory activities of red wines made from various grape cultivars. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chira, K.; Pacella, N.; Jourdes, M.; Teissedre, P.L. Chemical and sensory evaluation of Bordeaux wines (Cabernet-Sauvignon and Merlot) and correlation with wine age. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1971–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratil, P.; Kubáň, V.; Fojtová, J. Comparison of the phenolic content and total antioxidant activity in wines as determined by spectrophotometric methods. Czech J. Food Sci. 2008, 26, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Zurbano, P.; Ferreira, V.; Pefia, C.; Escudero, A.; Serrano, F.; Cacho, J. Prediction of Oxidative Browning in White Wines as a Function of Their Chemical Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 2813–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panprivech, S.; Lerno, L.A.; Brenneman, C.A.; Block, D.E.; Oberholster, A. Investigating the Effect of Cold Soak Duration on Phenolic Extraction during Cabernet Sauvignon Fermentation. Molecules 2015, 20, 7974–7989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieri, F.; Campo, M.; Cassiani, C.; Urciuoli, S.; Jurkhadze, K.; Romani, A. Analysis of aroma and polyphenolic compounds in Saperavi red wine vinified in Qvevri. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 6492–6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Ortín, A.B.; Busse-Valverde, N.; Fernández-Fernández, J.I.; Gómez-Plaza, E.; Gil-Muñoz, R. The extraction kinetics of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins from grape to wine in three different varieties. OENO One 2016, 50, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Capuano, R.; Lecce, L.; Fragasso, M.G.; Moio, L. Extraction of phenolic compounds from ‘Aglianico’ and ‘Uva Di Troia’ grape skins and seeds in model solutions: Influence of ethanol and maceration time. Vitis J. Grapevine Res. 2009, 48, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, Z.; Kállay, M. Polyphenol contents of skin-contact fermented white wines. Acta Aliment. 2019, 48, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, B.; Bieniasz, M.; Kostecka-Gugała, A. The content of selected bioactive compounds in wines produced from dehydrated grapes of the hybrid cultivar ‘Hibernal’ as a factor determining the method of producing straw wines. Foods 2022, 11, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alencar, N.M.M.; Cazarin, C.B.B.; Corrêa, L.C.; Maróstica Junior, M.R.; Biasoto, A.C.T.; Behrens, J.H. Influence of maceration time on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of the Syrah must and wine. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ružić, I.; Škerget, M.; Knez, Ž.; Runje, M. Phenolic content and antioxidant potential of macerated white wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 233, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casassa, L.F.; Huff, R.; Steele, N.B. Chemical consequences of extended maceration and post-fermentation additions of grape pomace in Pinot Noir and Zinfandel wines from the Central Coast of California (USA). Food Chem. 2019, 300, 125147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francesca, N.; Romano, R.; Sannino, C.; le Grottaglie, L.; Settanni, L.; Moschetti, G. Evolution of microbiological and chemical parameters during red wine making with extended post-fermentation maceration. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 171, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Verbaere, A.; Meudec, E.; Cheynier, V.; Sommerer, N. Straightforward method to quantify GSH, GSSG, GRP, and hydroxycinnamic acids in wines by UPLC-MRM-MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baderschneider, B.; Winterhalter, P. Isolation and characterization of novel benzoates, cinnamates, flavonoids, and lignans from Riesling wine and screening for antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2788–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recamales, Á.F.; Sayago, A.; González-Miret, M.L.; Hernanz, D. The effect of time and storage conditions on the phenolic composition and colour of white wine. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monagas, M.; Bartolomé, B.; Gómez-Cordovés, C. Updated knowledge about the presence of phenolic compounds in wine. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 85–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, P.; Doco, T.; Scollary, G.R. The influence of wine polymers on the spontaneous precipitation of calcium tartrate in a model wine solution. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 2676–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prezioso, I.; Fioschi, G.; Rustioni, L.; Mascellani, M.; Natrella, G.; Venerito, P.; Gambacorta, G.; Paradiso, V.M. Influence of prolonged maceration on phenolic compounds, volatile profile and sensory properties of wines from Minutolo and Verdeca, two Apulian white grape varieties. LWT 2024, 192, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milat, A.M.; Boban, M.; Teissedre, P.L.; Šešelja-Perišin, A.; Jurić, D.; Skroza, D.; Generalić-Mekinić, I.; Ivica Ljubenkov, I.; Volarević, J.; Rasines-Perea, Z.; et al. Effects of oxidation and browning of macerated white wine on its antioxidant and direct vasodilatory activity. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 59, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Meudec, E.; Eder, M.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Sommerer, N.; Cheynier, V. Targeted filtering reduces the complexity of UHPLC-OrbitrapHRMS data to decipher polyphenol polymerization. Food Chem. 2017, 227, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.; Bosman, G.; du Toit, W.; Aleixandre-Tudo, J.L. White wine phenolics: Current methods of analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drinkine, J.; Lopes, P.; Kennedy, J.A.; Teissedre, P.L.; Saucier, C. Ethylidene-bridged flavan-3-ols in red wine and correlation with wine age. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6292–6299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drinkine, J.; Lopes, P.; Kennedy, J.A.; Teissedre, P.L.; Saucier, C. Analysis of ethylidene-bridged flavan-3-ols in wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockenbach, I.I.; Jungfer, E.; Ritter, C.; Santiago-Schübel, B.; Thiele, B.; Fett, R.; Galensa, R. Characterization of flavan-3-ols in seeds of grape pomace by CE, HPLC-DAD-MSn and LC-ESI-FTICR-MS. Food Res. Int. 2012, 48, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, D.W.; Parker, M.; Smith, P.A. Flavonol composition of Australian red and white wines determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2008, 14, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Bañuelos, G.; Buica, A.; De Villiers, A.; Du Toit, W.J. Impact of time, oxygen and different anthocyanin to tannin ratios on the precipitate and extract composition using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2019, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosso, M.; Panighel, A.; Dalla Vedova, A.; Flamini, R. Elucidations on the structures of some putative flavonoids identified in postharvest withered grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) by quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectr. 2020, 55, e4639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamini, R. Recent applications of mass spectrometry in the study of grape and wine polyphenols. Int. Sch. Res. Notices 2013, 1, 813563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, A.; Cabooter, D.; Lynen, F.; Desmet, G.; Sandra, P. High-efficiency high performance liquid chromatographic analysis of red wine anthocyanins. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 4660–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraige, K.; Pereira-Filho, E.R.; Carrilho, E. Fingerprinting of anthocyanins from grapes produced in Brazil using HPLC-DAD-MS and exploratory analysis by principal component analysis. Food Chem. 2014, 145, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, A.; Vanhoenacker, G.; Majek, P.; Sandra, P. Determination of anthocyanins in wine by direct injection liquid chromatography–diode array detection–mass spectrometry and classification of wines using discriminant analysis. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1054, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Hu, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zang, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, C.; Xu, J. Quality characteristics and anthocyanin profiles of different Vitis amurensis grape cultivars and hybrids from Chinese germplasm. Molecules 2021, 26, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.; Mullen, W.; Landrault, N.; Teissedre, P.L.; Lean, M.E.; Crozier, A. Variations in the profile and content of anthocyanins in wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon and hybrid grapes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, P.; Stander, M.A.; de Villiers, A. Advanced ultra high pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometric methods for the screening of red wine anthocyanins and derived pigments. J. Chromatogr. A 2012, 1235, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, S.; Losito, I.; Gambacorta, G.; Notte, E.L.; Palmisano, F.; Zambonin, P.G. Simultaneous separation and identification of oligomeric procyanidins and anthocyanin-derived pigments in raw red wine by HPLC-UV-ESI-MSn. J. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 41, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, L.; D’Argentina, S.B.; Paissoni, M.A.; Segade, S.R.; Rolle, L.; Giacosa, S. Phenolic budget in red winemaking: Influence of maceration temperature and time. Food Chem. 2025, 482, 144159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kocabey, N.; Yilmaztekin, M.; Hayaloglu, A.A. Effect of maceration duration on physicochemical characteristics, organic acid, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of red wine from Vitis vinifera L. Karaoglan. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 53, 3557–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisov, N.; Čakar, U.; Milenković, D.; Čebela, M.; Vuković, G.; Despotović, S.; Petrović, A. The influence of Cabernet Sauvignon ripeness, healthy state and maceration time on wine and fermented pomace phenolic profile. Fermentation 2023, 9, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattivi, F.; Arapitsas, P.; Perenzoni, D.; Guella, G. Influence of storage conditions on the composition of red wines. In Advances in Wine Research; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontañón, I.; Sánchez, D.; Sáez, V.; Mattivi, F.; Ferreira, V.; Arapitsas, P. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry-based metabolomics for understanding the compositional changes induced by oxidative or anoxic storage of red wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 13367–13379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.L. Wine phenolics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 957, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzachristas, A.; Dasenaki, M.E.; Aalizadeh, R.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Proestos, C. Development of a wine metabolomics approach for the authenticity assessment of selected Greek red wines. Molecules 2021, 26, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radovanović Vukajlović, T.; Philipp, C.; Eder, P.; Šala, M.; Šelih, V.S.; Vanzo, A.; Šuklje, K.; Lisjak, K.; Sternad Lemut, M.; Eder, R.; et al. New Insight on the Formation of 2-Aminoacetophenone in White Wines. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voce, S.; Škrab, D.; Vrhovsek, U.; Battistutta, F.; Comuzzo, P.; Sivilotti, P. Compositional characterization of commercial sparkling wines from cv. Ribolla Gialla produced in Friuli Venezia Giulia. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2279–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Scanff, M.; Marcourt, L.; Rutz, A.; Albertin, W.; Wolfender, J.L.; Marchal, A. Untargeted metabolomics analyses to identify a new sweet compound released during post-fermentation maceration of wine. Food Chem. 2024, 461, 140801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A. Concept, mechanism, and applications of phenolic antioxidants in foods. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomelli, C.; Miranda Fda, S.; Gonçalves, N.S.; Spinelli, A. Antioxidant activity of phenolic and related compounds: A density functional theory study on the O-H bond dissociation enthalpy. Redox Rep. 2004, 9, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Hampsch-Woodill, M.; Prior, R.L. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4619–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, G.; Prior, R.L. Measurement of oxygen radical absorbance capacity in biological samples. Methods Enzymol. 1999, 299, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, M.C. Use and Abuse of the DPPH• Radical. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8765–8776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Chu, L.; Wei, Y.; Wang, D.; Cai, S.; Zhou, F.; Ji, B. Relationship Between the Structures of Flavonoids and Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity Values: A Quantum Chemical Analysis. J. Physic. Chem. A 2013, 117, 1784−1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, H.; Lu, J. Phenolic concentrations and antioxidant properties of wines made from North American grapes grown in China. Molecules 2012, 17, 3304–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryland, B.L.; McCann, S.D.; Brunold, T.C.; Stahl, S.S. Mechanism of alcohol oxidation mediated by copper(II) and nitroxyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12166–12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, J.M.; Ryland, B.L.; Stahl, S.S. Mechanism of Copper(I)/TEMPO-Catalyzed Aerobic Alcohol Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliaga, C.; Lissi, E.A.; Augusto, O.; Linares, E. Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of a nitroxide radical (Tempol) with a phenolic antioxidant. Free Rad. Res. 2003, 37, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszowy-Tomczyk, M. How to express the antioxidant properties of substances properly? Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 6157–6167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitis International Variety Catalogue (VIVC). Julius Kühn-Institut (JKI), Institute for Grapevine Breeding Geilweilerhof, Siebeldingen, Germany. Available online: https://www.vivc.de/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Myśliwiec, R.; Bosak, W.; Zamojska, A. 101 Odmian Winorośli; Fundacja na Rzecz Rozwoju i Promocji Winiarstwa GALICJA VITIS: Krakow, Poland, 2023. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- National Agricultural Support Center. Ministry of Economic Development and Technology Warsaw, Poland. 2023. Available online: https://www.enoportal.pl/aktualnosci/struktura-powierzchni-upraw-winorosli-w-polskich-winnicach-2023/ (accessed on 16 July 2025). (In Polish).

- OIV—International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Compendium of International Methods of Wine and Must Analysis; Hôtel Bouchu dit d’Esterno: Dijon, France, 2025; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmeyer, H.U.; Bernt, E.; Schidt, F.; Stork, H. Méthodes D’analyse Enzymatique, 2nd ed.; Verlag Chemie: Weinheim/Bergstraße, Germany, 1970; p. 1163. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, M. Simple Methods for Rapid Determination of Sulfite in Food Products. Food Control 2006, 17, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo-Martínez, J.-F.; Enseñat-Berea, M.-L.; Fernández-Paz, J.; González-Castro, M.-J. Validation of a fast automated photometric method for the analysis of sulfur dioxide in wines. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2024, 250, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Caputi, A. Colorimetric Determination of Tartaric Acid in Wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1970, 21, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Rosa, M.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Meth. Enzymol. 1999, 299, 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Cajka, T.; Kind, T.; Ma, Y.; Higgins, B.; Ikeda, K.; Kanazawa, M.; VanderGheynst, J.; Fiehn, O.; Arita, M. MS-DIAL: Data-independent MS/MS deconvolution for comprehensive metabolome analysis. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dührkop, K.; Fleischauer, M.; Ludwig, M.; Aksenov, A.A.; Melnik, A.V.; Meusel, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Rousu, J.; Böcker, S. SIRIUS 4: A rapid tool for turning tandem mass spectra into metabolite structure information. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, B.; Chang, T.; Huang, D.; Prior, R.L. Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity by Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Using Fluorescein as the Fluorescence Probe: First Action 2012.23. J. AOAC Int. 2013, 96, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilges, M.J.; Walczak, T.; Swartz, H.M. 1 GHz in vivo ESR spectrometer operating with surface probe. Phys. Med. 1989, 5, 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET). Level 2 Award in Wines: Looking Behind the Label, Issue 2; Wine & Spirit Education Trust: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097−2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cultivar | Extract (°Brix) | pH | Total Acidity, TAm (Tartaric Acid eq., TAE; g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Johanniter’ | 20 | 3.26 | 7.12 |

| ‘Regent’ | 18 | 3.62 | 8.33 |

| Wine Sample | pH | Total Acidity TAw (TAE; g/L) | Alc. Vol. (%) | Residual Sugar (g/L) | SO2 Free (mg/L) | SO2 Total (mg/L) | L-Malic Acid (g/L) | Tartaric Acid (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J0 | 3.23 | 8.69 | 12.0 | 0.08 | <3 * | 66 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| J4 | 3.59 | 8.53 | 11.4 | 0.08 | 5 | 40 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| J8 | 3.65 | 8.54 | 11.5 | 0.05 | 13 | 37 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| J12 | 3.63 | 8.10 | 11.7 | 0.06 | <3 * | 15 | 2.3 | 1.6 |

| J16 | 3.65 | 8.06 | 11.5 | 0.05 | 3 | 21 | 2.1 | 1.5 |

| J20 | 3.67 | 7.93 | 11.6 | 0.05 | <3 * | 35 | 2.3 | 1.4 |

| R0 | 3.75 | 8.19 | 10.0 | 0.03 | <3 * | 29 | 1.70 | 2.3 |

| R4 | 3.98 | 7.24 | 9.5 | 0.10 | 3 | 14 | 0.03 | 2.7 |

| R8 | 3.94 | 6.96 | 9.5 | 0.09 | 6 | <10 | 0.07 | 2.4 |

| R12 | 3.91 | 6.99 | 9.4 | 0.09 | 13 | 19 | 0.04 | 2.4 |

| R16 | 3.87 | 7.20 | 9.6 | 0.06 | 9 | 21 | 0.03 | 2.2 |

| R20 | 3.86 | 8.08 | 9.3 | 0.09 | 12 | 19 | 0.04 | 2.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kostecka-Gugała, A.; Stanula, J.; Żuchowski, J.; Kaszycki, P. Optimizing Wine Production from Hybrid Cultivars: Impact of Grape Maceration Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2026, 31, 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010179

Kostecka-Gugała A, Stanula J, Żuchowski J, Kaszycki P. Optimizing Wine Production from Hybrid Cultivars: Impact of Grape Maceration Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):179. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010179

Chicago/Turabian StyleKostecka-Gugała, Anna, Jacek Stanula, Jerzy Żuchowski, and Paweł Kaszycki. 2026. "Optimizing Wine Production from Hybrid Cultivars: Impact of Grape Maceration Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds" Molecules 31, no. 1: 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010179

APA StyleKostecka-Gugała, A., Stanula, J., Żuchowski, J., & Kaszycki, P. (2026). Optimizing Wine Production from Hybrid Cultivars: Impact of Grape Maceration Time on the Content of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules, 31(1), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010179