Antifouling Epoxy Coatings with Scots Pine Bark Extracts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis

2.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) Quantitative Analysis

2.3. Concentrated Extract—Density, Total Solid Content and TPC

2.4. Preparation of Epoxy Compositions

2.5. Shore D Hardness

2.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis of Curing Process

2.7. Preparation of Samples for Tests

2.8. Density

2.9. Antibacterial Activity

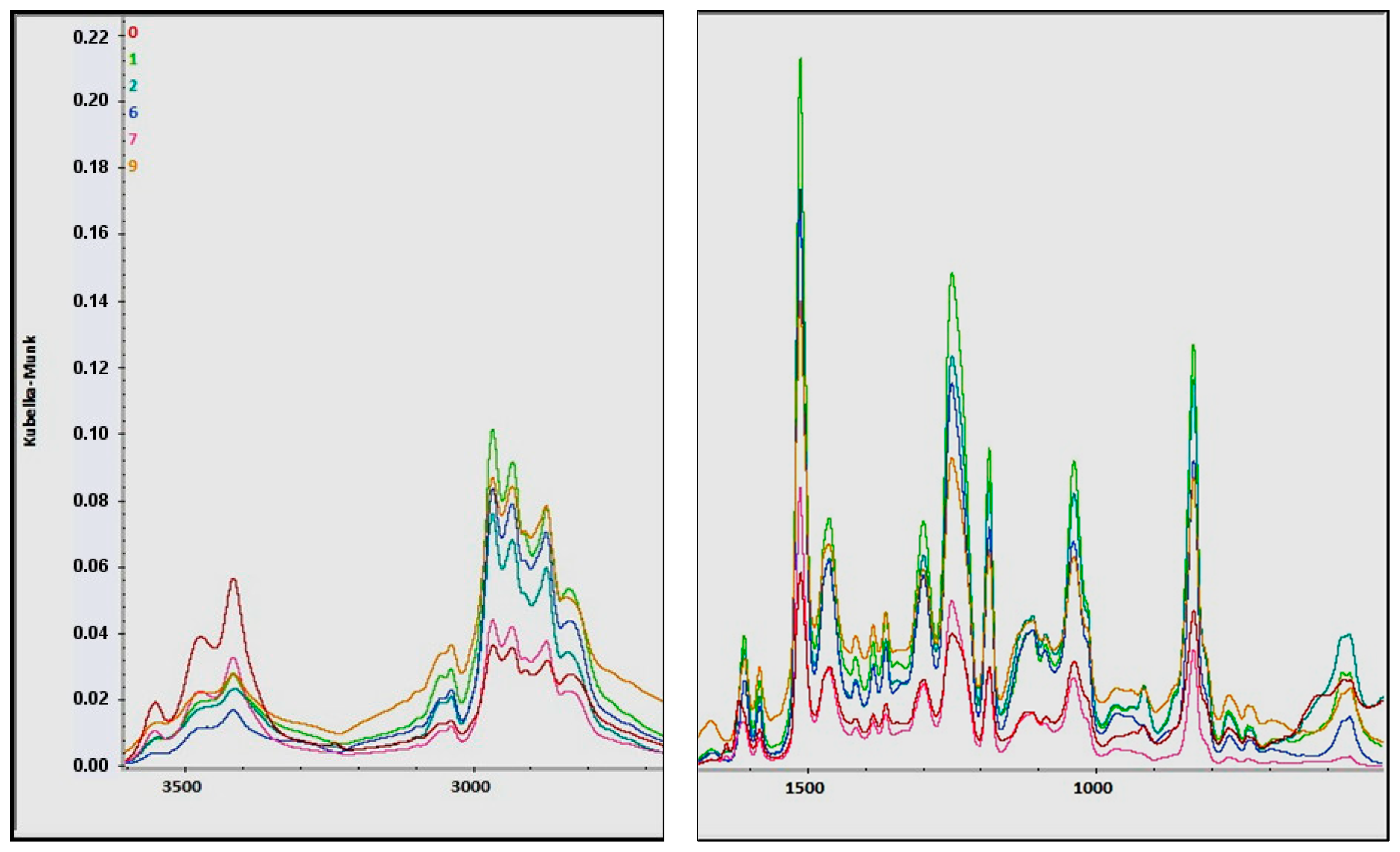

2.10. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis of Composites

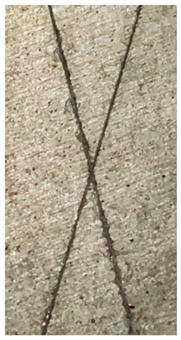

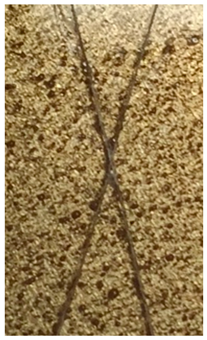

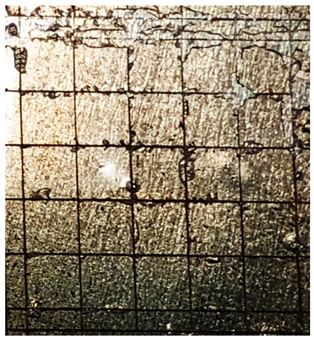

2.11. Adhesion Tests

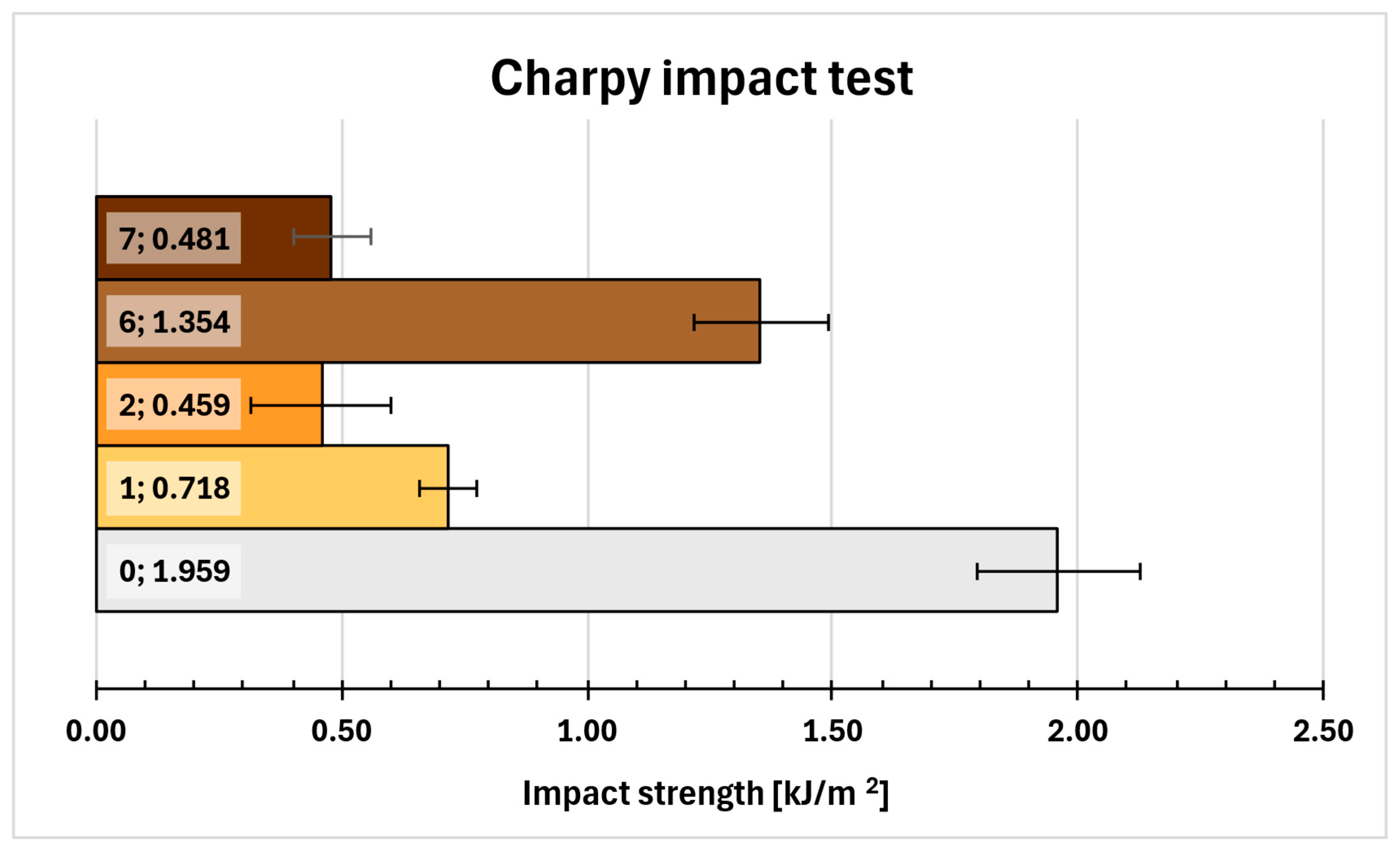

2.12. Charpy Impact Test

2.13. Three-Point Bending Test

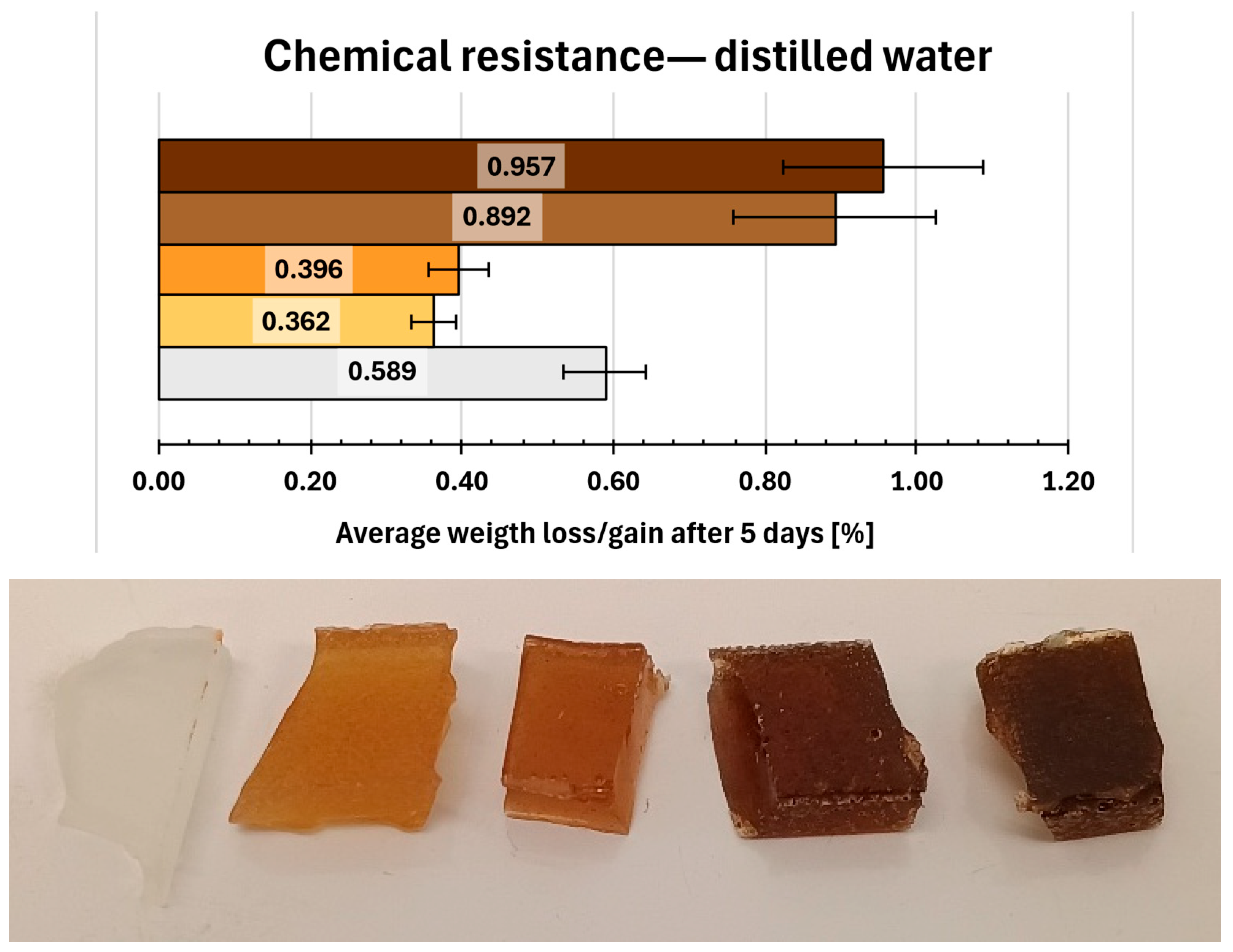

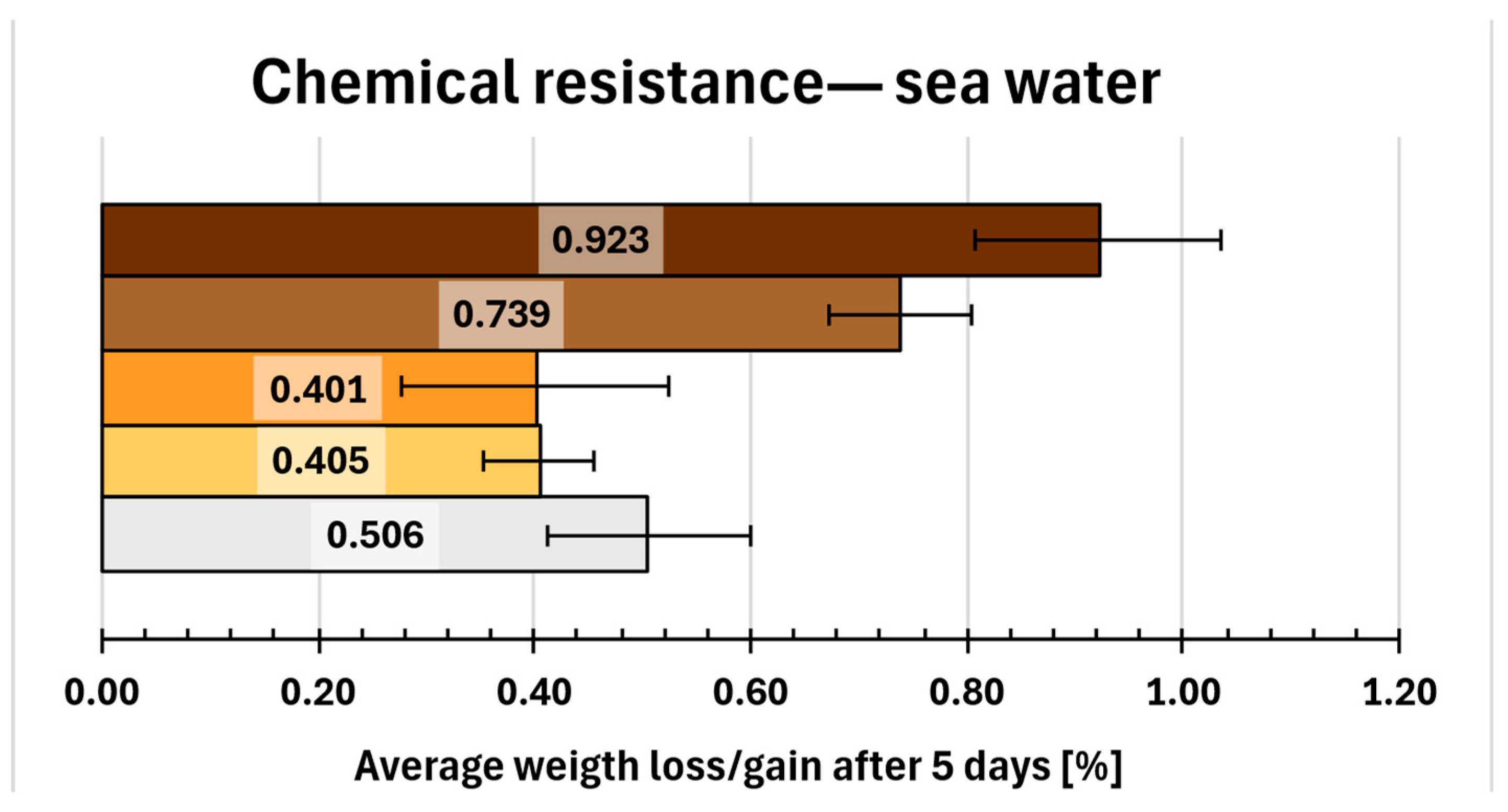

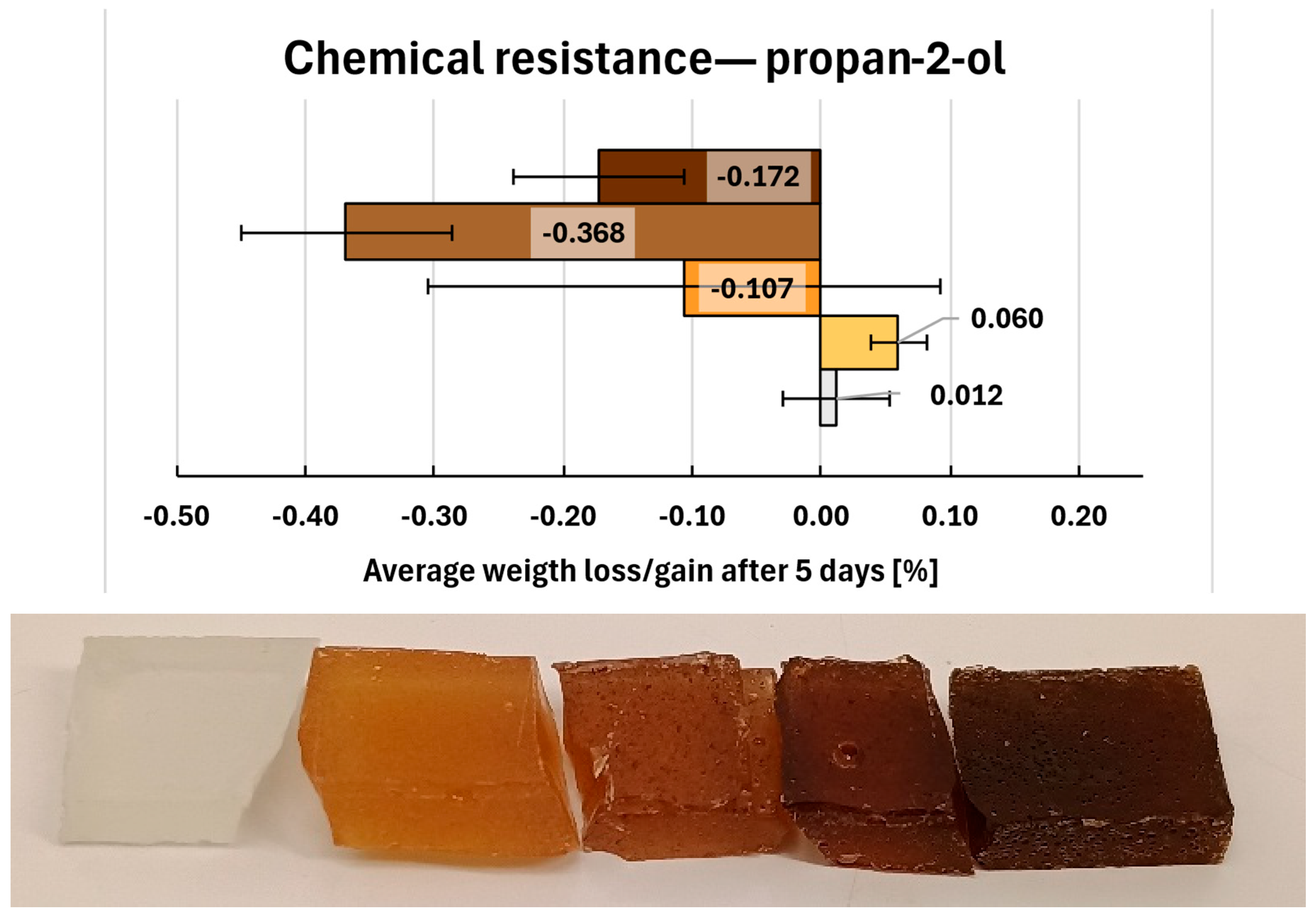

2.14. Chemical Resistance

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Scots Pine Bark Grinding

4.3. Extraction for Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

4.4. High Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

4.5. Total Phenolic Content Quantitative Analysis

4.6. Concentrated Extract—Preparation

4.7. Concentrated Extract—Density, Total Solid Content and TPC

4.8. Preparation of Epoxy Compositions

4.9. Shore D Hardness

4.10. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis of Curing Process

4.11. Preparation of Samples for Tests

4.12. Density

4.13. Antibacterial Activity

4.14. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Analysis of Composites

4.15. Adhesion Tests

4.16. Charpy Impact Test and Three-Point Bending Test

4.17. Chemical Resistance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ha, Z.; Lei, L.; Zhou, M.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X.; Mao, P.; Fan, B.; Shi, S. Bio-Based Waterborne Polyurethane Coatings with High Transparency, Antismudge and Anticorrosive Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 7427–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Du, T.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Photothermal MOF-Based Multifunctional Coating with Passive and Active Protection Synergy. ACS Appl. Eng. Mater. 2023, 1, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fang, Y.; Ou, Y.; Shi, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, L.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Synergistic Anti-Corrosion and Anti-Wear of Epoxy Coating Functionalized with Inhibitor-Loaded Graphene Oxide Nanoribbons. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 220, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Xiao, L.; Zhang, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, J. Superhydrophobic Composite Coating with Excellent Mechanical Durability. Coatings 2022, 12, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, N.; Wang, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, H.; Cao, S.; Liu, Y.; Gao, C. Fabrication of an Anti-Fouling Coating Based on Epoxy Resin with a Double Antibacterial Effect via an in Situ Polymerization Strategy. Prog. Org. Coat. 2023, 184, 107837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, Z.; Hu, J.; Meng, F.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Q. An Imine--Functionalized Silicone--Based Epoxy Coating with Stable Adhesion and Controllable Degradation for Enhanced Marine Antifouling and Anticorrosion Properties. Chem.–A Eur. J. 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shu, B.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Wu, T.; Xiang, Z.; Yang, S.; Yang, Z.; Hu, Y. Mussel-Inspired Synergistic Anticorrosive Coatings for Steel Substrate Prepared Basing on Fully Bio-Based Epoxy Resin and Biomass Modified Graphene Nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 693, 134038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veedu, K.K.; Mohan, S.; Somappa, S.B.; Gopalan, N.K. Eco-Friendly Anticorrosive Epoxy Coating from Ixora Leaf Extract: A Promising Solution for Steel Protection in Marine Environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 340, 130750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karattu Veedu, K.; Banyangala, M.; Peringattu Kalarikkal, T.; Balappa Somappa, S.; Karimbintherikkal Gopalan, N. Green Approach in Anticorrosive Coating for Steel Protection by Gliricidia Sepium Leaf Extract and Silica Hybrid. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 369, 120967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ashraf, S.M.; Naqvi, F.; Yadav, S.; Hasnat, A. A Polyesteramide from Pongamia Glabra Oil for Biologically Safe Anticorrosive Coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2003, 47, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C.; Xiong, W.; Mu, Y.; Pei, D.; Wan, X. Mussel-Inspired Polymeric Coatings with the Antifouling Efficacy Controlled by Topologies. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 9295–9304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Bing, W.; Jin, E.; Tian, L.; Jiang, Y. Bioinspired PDMS–Phosphor–Silicone Rubber Sandwich--Structure Coatings for Combating Biofouling. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 1901577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matamala, G.; Smeltzer, W.; Droguett, G. Comparison of Steel Anticorrosive Protection Formulated with Natural Tannins Extracted from Acacia and from Pine Bark. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 1351–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, L.F.; Contreras, D.; Jaramillo, A.F.; Carrasco, C.; Fernández, K.; Schwederski, B.; Rojas, D.; Melendrez, M.F. Study of Anticorrosive Coatings Based on High and Low Molecular Weight Polyphenols Extracted from the Pine Radiata Bark. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 127, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.F.; Montoya, L.F.; Prabhakar, J.M.; Sanhueza, J.P.; Fernández, K.; Rohwerder, M.; Rojas, D.; Montalba, C.; Melendrez, M.F. Formulation of a Multifunctional Coating Based on Polyphenols Extracted from the Pine Radiata Bark and Functionalized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Evaluation of Hydrophobic and Anticorrosive Properties. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 135, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.; Almeida, J.R.; Cidade, H.; Correia-da-Silva, M. Proof of Concept of Natural and Synthetic Antifouling Agents in Coatings. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmechtyk, T. Scots Pine Bark Extracts as Co-Hardeners of Epoxy Resins. Molecules 2024, 30, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Zhou, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Yan, T.; Li, Y. Fabrication of Antibacterial Poly (L-Lactic Acid)/Tea Polyphenol Blend Films via Reactive Blending Using SG Copolymer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Ashby, R.; Fan, X.; Moreau, R.A.; Strahan, G.D.; Nuñez, A.; Ngo, H. Phenolic Fatty Acid-Based Epoxy Curing Agent for Antimicrobial Epoxy Polymers. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 141, 105536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerbacher, A.; Kandasamy, D.; Ullah, C.; Schmidt, A.; Wright, L.P.; Gershenzon, J. Flavanone-3-Hydroxylase Plays an Important Role in the Biosynthesis of Spruce Phenolic Defenses Against Bark Beetles and Their Fungal Associates. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Kandasamy, D.; Krokene, P.; Chen, J.; Gershenzon, J.; Hammerbacher, A. Fungal Associates of the Tree-Killing Bark Beetle, Ips Typographus, Vary in Virulence, Ability to Degrade Conifer Phenolics and Influence Bark Beetle Tunneling Behavior. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 38, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, L.; Wynstra, J.; Kurkjy, R.P. Glycidyl Ether Reactions with Amines. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1956, 48, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czub, P.; Bończa, Z.; Penczek, P.; Pielichowski, J. Chemistry and Technology of Epoxy Resins, 4th ed.; Penczek, P., Ed.; WNT: Warsaw, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, A.-S.; Tayouo, R.; Boutevin, B.; David, G.; Caillol, S. A Perspective Approach on the Amine Reactivity and the Hydrogen Bonds Effect on Epoxy-Amine Systems. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 123, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennemann, C.; Paul, W.; Binder, K.; Dünweg, B. Molecular-Dynamics Simulations of the Thermal Glass Transition in Polymer Melts: α-Relaxation Behavior. Phys. Rev. E 1998, 57, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.Y.; Zhang, Z.L.; Kristiansen, H.; Redford, K.; Fonnum, G.; Modahl, G.I. Crosslinking Effect on the Deformation and Fracture of Monodisperse Polystyrene-Co-Divinylbenzene Particles. Express Polym. Lett. 2013, 7, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, P.; Dong, S. The Influence of Crosslink Density on the Failure Behavior in Amorphous Polymers by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Materials 2016, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliaz, N.; Ron, E.Z.; Gozin, M.; Younger, S.; Biran, D.; Tal, N. Microbial Degradation of Epoxy. Materials 2018, 11, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuccetelli, P.; Maisto, F.; Kraková, L.; Grilli, A.; Takáčová, A.; Šišková, A.O.; Pangallo, D. Evaluation of Microbial Degradation of Thermoplastic and Thermosetting Polymers by Environmental Isolates. Coatings 2024, 14, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, S.M.; Fayyad, D.M.; Ragab, M.H. Effect of Enterococcus Faecalis on Pushout Bond Strength of Resin Based Sealer (An In-Vitro Study). Dent. Sci. Updates 2024, 5, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, P.T.; Yan, J.; Vaubourgeix, J.; Becattini, S.; Lampen, N.; Motzer, A.; Larson, P.J.; Dannaoui, D.; Fujisawa, S.; Xavier, J.B.; et al. Intestinal Bile Acids Induce a Morphotype Switch in Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus That Facilitates Intestinal Colonization. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 695–705.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenger, V.; Verdu, J.; Francillette, J.; Hoarau, P.; Morel, E. Infra-Red Study of Hydrogen Bonding in Amine-Crosslinked Epoxies. Polymer 1987, 28, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schab-Balcerzak, E.; Janeczek, H.; Kaczmarczyk, B.; Bednarski, H.; Sęk, D.; Miniewicz, A. Epoxy Resin Cured with Diamine Bearing Azobenzene Group. Polymer 2004, 45, 2483–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.D.S. Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy. In Organic Spectroscopy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 52–106. [Google Scholar]

- Meiser, A.; Willstrand, K.; Possart, W. Influence of Composition, Humidity, and Temperature on Chemical Aging in Epoxies: A Local Study of the Interphase with Air. J. Adhes. 2010, 86, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannoy, R.; Tognetti, V.; Richaud, E. Experimental and Theoretical Insights on the Thermal Oxidation of Epoxy-Amine Networks. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 206, 110188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Preparation of Tea Tree Essential Oil@Chitosan-Arabic Gum Microcapsules and Its Effect on the Properties of Waterborne Coatings. Coatings 2025, 15, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, V.L.; Rossi, J.A. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1965, 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E2180; Test Method for Determining the Activity of Incorporated Antimicrobial Agent(s) in Polymeric or Hydrophobic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ISO 16276-2; Corrosion Protection of Steel Structures by Protective Paint Systems—Assessment of, and Acceptance Criteria for, the Adhesion/Cohesion (Fracture Strength) of a Coating. Part 2: Cross-Cut Testing and X-Cut Testing. International Organisation of Standardization: Vernier, Switzerland, 2025.

- ISO 2409; Paints and Varnishes—Cross-Cut Test. International Organisation of Standardization: Vernier, Switzerland, 2020.

| Extract Name | Abs765 | TPC [µg GAE/mL] |

|---|---|---|

| C120T60 | 0.9653 ± 0.0047 | 2674.99 ± 10.61 |

| U30T25 | 1.0186 ± 0.0065 | 2795.37 ± 14.68 |

| U15T60 | 0.9058 ± 0.0039 | 2540.62 ± 8.81 |

| Density [mg/mL] | TSC [%] | Abs765 | TPC [µg GAE/mL] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.84 ± 0.04 | 93.0 ± 1.9 | 0.765 ± 0.069 | 5667.6 ± 394.8 |

| PHR Ratio | Percentage Share [%] | Selective Ratios | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epi5 | Z-1 | ex | Epi5 | Z-1 | ex | Z-1/Epi5 | ex/Epi5 | ex/Z-1 | |

| 0 | 100 | 12 | 0 | 89.29 | 10.71 | 0.00 | 0.120 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 1 | 100 | 8 | 4 | 89.29 | 7.14 | 3.57 | 0.080 | 0.040 | 0.500 |

| 2 | 100 | 6 | 6 | 89.29 | 5.36 | 5.36 | 0.060 | 0.060 | 1.000 |

| 3 | 100 | 4 | 8 | 89.29 | 3.57 | 7.14 | 0.040 | 0.080 | 2.000 |

| 4 | 100 | 3 | 9 | 89.29 | 2.68 | 8.04 | 0.030 | 0.090 | 3.000 |

| 5 | 100 | 2 | 12 | 87.72 | 1.75 | 10.53 | 0.020 | 0.120 | 6.000 |

| 6 | 90 | 8 | 14 | 80.36 | 7.14 | 12.50 | 0.089 | 0.156 | 1.750 |

| 7 | 90 | 6 | 16 | 80.36 | 5.36 | 14.29 | 0.067 | 0.178 | 2.667 |

| 8 | 90 | 4 | 18 | 80.36 | 3.57 | 16.07 | 0.044 | 0.200 | 4.500 |

| 9 | 80 | 6 | 26 | 71.43 | 5.36 | 23.21 | 0.075 | 0.325 | 4.333 |

| Molar Quantities [mol] Calculated for PHR Ratio | nH of Groups Reacting with Epoxy Ring to Epoxy Groups Molar Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy Groups | nH of Amine Groups * | nH of Groups Reacting with Epoxy Ring ** | ||

| 0 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.354–0.492 | 0.707–0.985 | 1.37–2.05 |

| 1 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.236–0.328 | 0.472–0.656 | 0.91–1.37 |

| 2 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.177–0.246 | 0.354–0.492 | 0.69–1.03 |

| 3 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.118–0.164 | 0.236–0.328 | 0.46–0.68 |

| 4 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.088–0.123 | 0.177–0.246 | 0.34–0.51 |

| 5 | 0.480–0.515 | 0.059–0.082 | 0.118–0.164 | 0.23–0.34 |

| 6 | 0.432–0.464 | 0.236–0.328 | 0.472–0.656 | 1.02–1.52 |

| 7 | 0.432–0.464 | 0.177–0.246 | 0.354–0.492 | 0.76–1.14 |

| 8 | 0.432–0.464 | 0.118–0.164 | 0.236–0.328 | 0.51–0.76 |

| 9 | 0.384–0.412 | 0.177–0.246 | 0.354–0.492 | 0.86–1.28 |

| Composition | Enthalpy [J] | Weight of Sample [mg] | Specific Enthalpy [J/g] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | −14.640 | 49.0 | −298.78 |

| 1 | −5.880 | 47.0 | −125.11 |

| 2 | −4.120 | 38.6 | −106.74 |

| 3 | −0.517 | 32.3 | −16.01 |

| 6 | −6.240 | 49.0 | −127.35 |

| 7 | −5.420 | 40.8 | −132.84 |

| 8 | −5.510 | 39.3 | −140.20 |

| 9 | −4.490 | 36.3 | −123.69 |

| Composition | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteria Species | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Escherichia coli | −1.24 | −1.21 | −0.37 | −0.41 | −0.91 | 3.53 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | −0.12 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 4.92 |

| Bacillus subtilis | −0.19 | 0.60 | −0.35 | 0.83 | 0.30 | 3.20 |

| Enterococcus faecium | 5.00 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.83 | −0.14 | 5.00 |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | −0.33 | −0.74 | −0.57 | −0.80 | −1.00 | 5.34 |

| Composition | Cross Cut Adhesion Test | X-Cut Adhesion Test |

|---|---|---|

| 0 |  Rating: 1 |  Rating: 0 |

| 1 |  Rating: 0 |  Rating: 0 |

| 2 |  Rating: 1 |  Rating: 1 |

| 6 |  Rating: 2 |  Rating: 0 |

| 7 |  Rating: 2 |  Rating: 1 |

| 9 |  Rating: 2 |  Rating: 1 |

| Extract Name | Type of Extraction | Temperature [°C] | Extraction Time [min] |

|---|---|---|---|

| C120T60 | conventional | 60 | 120 |

| U30T25 | ultrasound-assisted | 25 | 30 |

| U15T60 | ultrasound-assisted | 60 | 15 |

| Time [min] | % of Phase A (Formic Acid 5% Water Solution) | % of Phase B (Acetonitrile) | Flow [mL/min] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 97 | 3 | 0.8 |

| 2 | 97 | 3 | 0.8 |

| 15 | 85 | 15 | 0.8 |

| 24 | 82 | 18 | 0.8 |

| 55 | 75 | 25 | 0.8 |

| 60 | 97 | 3 | 0.8 |

| Number: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Epidian 5 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 80 |

| Z-1 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 6 | |

| extract | 0 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Szmechtyk, T.; Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M.; Czyżowska, A. Antifouling Epoxy Coatings with Scots Pine Bark Extracts. Molecules 2026, 31, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010137

Szmechtyk T, Efenberger-Szmechtyk M, Czyżowska A. Antifouling Epoxy Coatings with Scots Pine Bark Extracts. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010137

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzmechtyk, Tomasz, Magdalena Efenberger-Szmechtyk, and Agata Czyżowska. 2026. "Antifouling Epoxy Coatings with Scots Pine Bark Extracts" Molecules 31, no. 1: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010137

APA StyleSzmechtyk, T., Efenberger-Szmechtyk, M., & Czyżowska, A. (2026). Antifouling Epoxy Coatings with Scots Pine Bark Extracts. Molecules, 31(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010137