Insights into Real Lignin Refining: Impacts of Multiple Ether Bonds on the Cracking of β-O-4 Linkages and Selectivity of Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

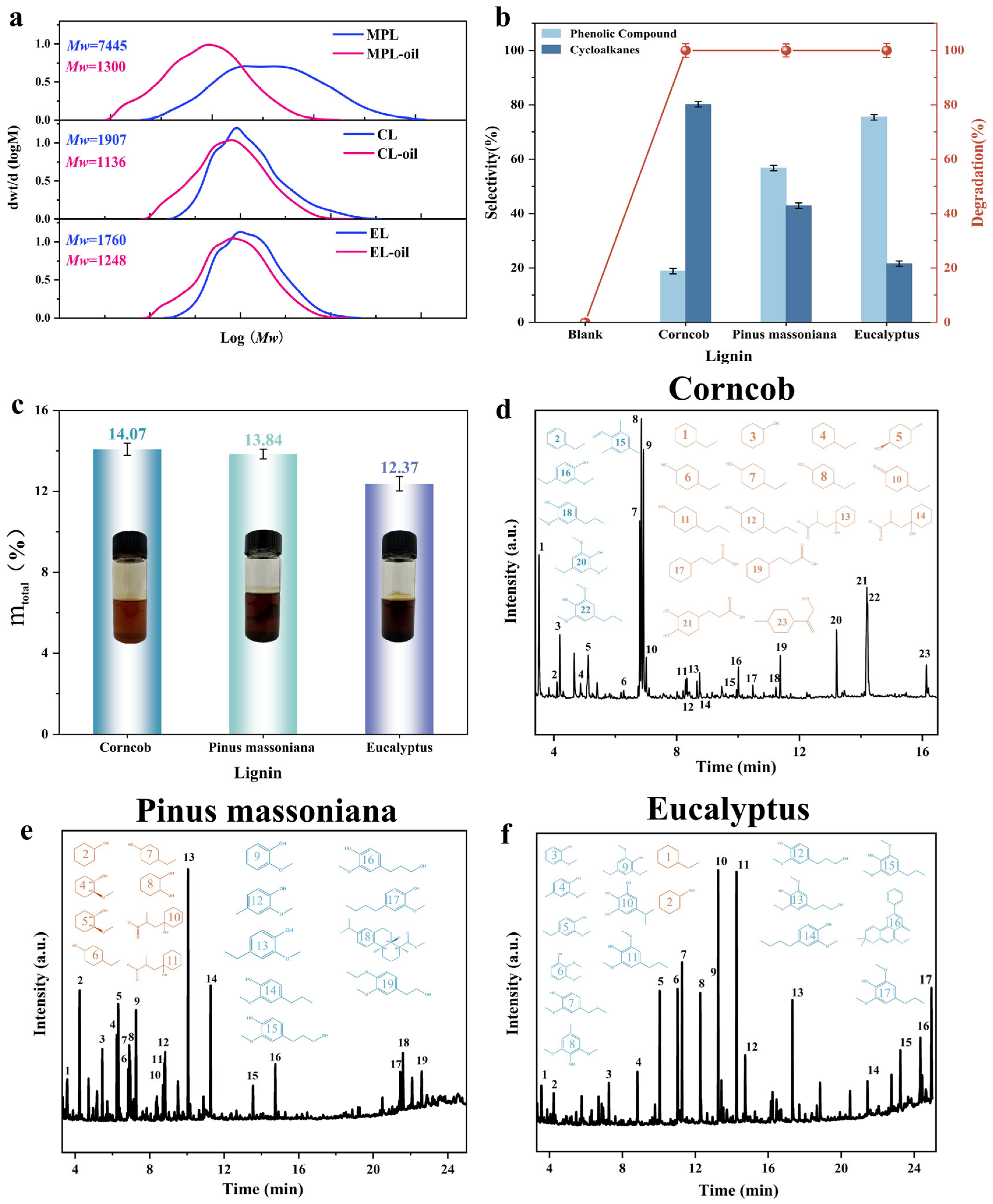

2.1. Characteristics of Three Real Lignins

2.2. Catalytic Depolymerization of Real Lignin

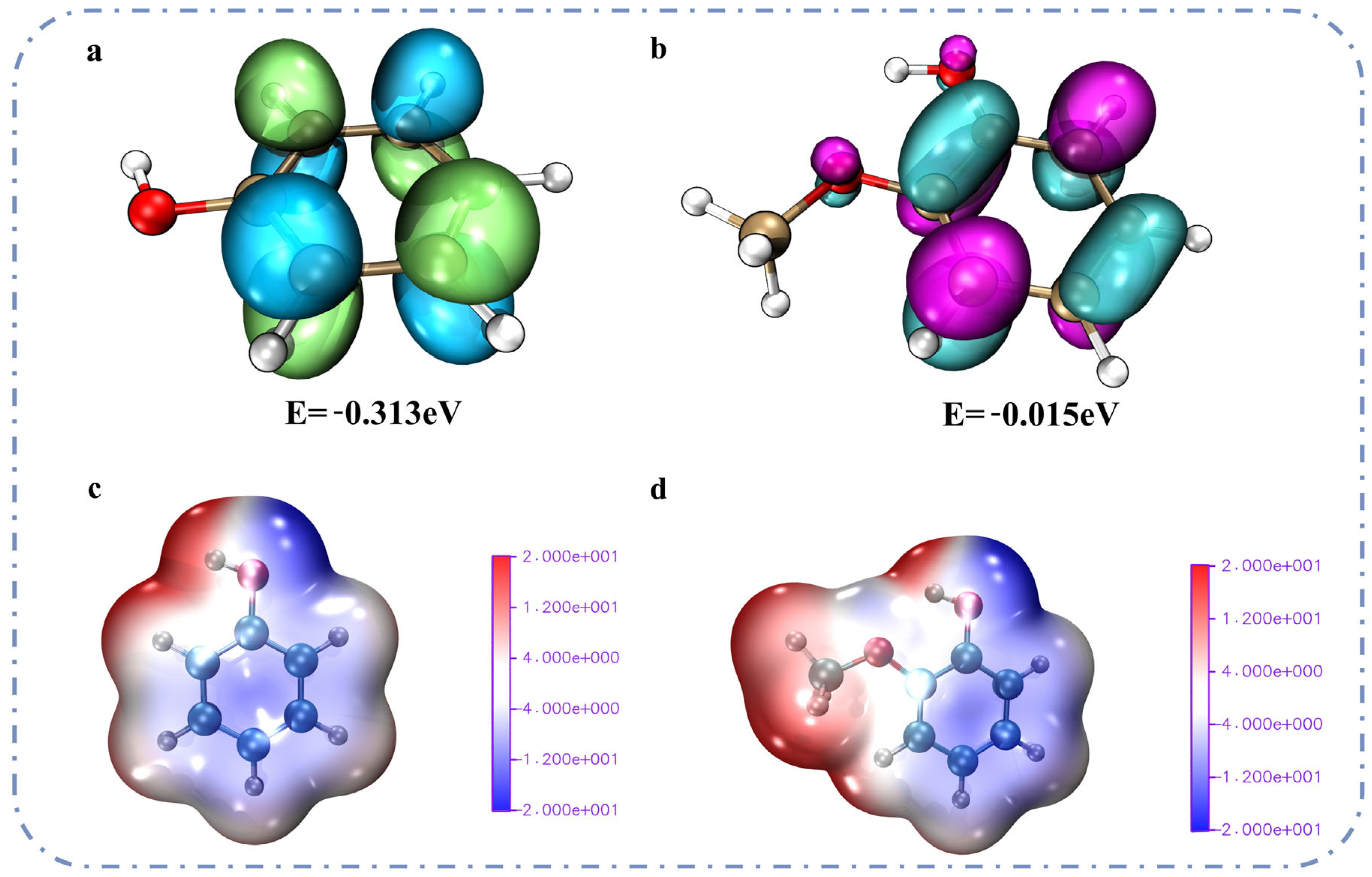

2.3. Influence Mechanism of Other Ether Bonds on the Catalytic Cracking of the β-O-4 Bond

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemicals and Materials

3.2. Decomposition of Lignin Model Compounds and Real Lignin Under an Air Atmosphere

3.3. Characterization of Lignins and Depolymerized Products

3.4. Activation Energy Calculation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuck, C.O.; Perez, E.; Horvath, I.T.; Sheldon, R.A.; Poliakoff, M. Valorization of biomass: Deriving more value from waste. Science 2012, 337, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallezot, P. Conversion of biomass to selected chemical products. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 1538–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, O.Y.; Clemmensen, I.; Meier, S.; Costa, C.A.E.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Hulteberg, C.P.; Riisager, A. On the oxidative valorization of lignin to high-value chemicals: A critical review of opportunities and challenges. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202201232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsanam, P.; Duolikun, T.; Babu, P.S.; Rokhum, S.L.; Johan, M.R. Recent developments in selective catalytic conversion of lignin into aromatics and their derivatives. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2020, 10, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, R.; Long, J.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, C.; Ma, L. Efficient and product-controlled depolymerization of lignin oriented by metal chloride cooperated with Pd/C. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 179, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Ma, R.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Song, G. Hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived phenols into cycloalkanes by atomically dispersed Pt-polyoxometalate catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 352, 124059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z.; Xiao, L.; Sun, R.; Fang, Y.; Song, G. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of lignins into phenolic compounds over carbon nanotube supported molybdenum oxide. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 7535–7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, C.; Fang, G.; Li, J.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, M.; Tao, D. Highly efficient conversion of lignin into diethyl maleate catalyzed by molybdenum-based hybrid catalysts. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 13780–13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Cao, J.; Xie, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of lignin and its model compounds to hydrocarbon fuels over a metal/acid Ru/HZSM-5 catalyst. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 19543–19552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Liu, P.; Xia, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhou, M. Catalytic conversion of lignin to liquid fuels with an improved h/ceff value over bimetallic NiMo-MOF-derived catalysts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 13937–13952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Cao, J.; Zhao, X.; Xie, T.; Zhao, M.; Wei, X. Bimetallic effects in the catalytic hydrogenolysis of lignin and its model compounds on Nickel-Ruthenium catalysts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2019, 194, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Yan, H.; Lei, Z.; Yan, J.; Ren, S.; Wang, Z.; Kang, S.; Shui, H. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of lignin and model compounds over highly dispersed Ni-Ru/Al2O3 without additional h 2. Fuel 2022, 326, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qi, Z.; Li, X.; Ji, J.; Luo, W.; Li, C.; Wang, A.; Zhang, T. ReOx/AC-catalyzed cleavage of C-O bonds in lignin model compounds and alkaline lignins. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, F.; Xie, J.; Qiu, L.; Xiao, J.; Liang, J.; Bai, Y.; Liu, F.; Cao, J. Selective hydrogenolysis of C-O bonds in lignin model compounds and kraft lignin over highly efficient NixCoyAl catalysts. Mol. Catal. 2023, 547, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Yu, H.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L.; Mu, T. Highly efficient cleavage of ether bonds in lignin models by transfer hydrogenolysis over dual-functional Ruthenium/montmorillonite. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4579–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, J.M.; Garcia, J.I.; Hormigon, Z.; Mayoral, J.A.; Saavedra, C.J.; Salvatella, L. Role of substituents in the solid acid-catalyzed cleavage of the β-O-4 linkage in lignin models. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 1837–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahive, C.W.; Deuss, P.J.; Lancefield, C.S.; Sun, Z.; Cordes, D.B.; Young, C.M.; Tran, F.; Slawin, A.M.Z.; de Vries, J.G.; Kamer, P.C.J.; et al. Advanced model compounds for understanding acid-catalyzed lignin depolymerization: Identification of renewable aromatics and a lignin-derived solvent. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8900–8911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, R.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, B.; You, H.; Zhong, Z.; He, Y. Enhanced hydrogenolysis of enzymatic hydrolysis lignin over in situ prepared RuNi bimetallic catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 41564–41572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Wang, S. Hydrodeoxygenation of lignin-derived monomers and dimers over a Ru supported solid super acid catalyst for cycloalkane production. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2020, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Q. Mild selective oxidative cleavage of lignin C-C bonds over a copper catalyst in water. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 7030–7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Yang, K.; Lin, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, Y.; Ye, X.; Song, L.; Lin, C.; Yang, G.; Liu, M. Selective production of cycloalkanes through the catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of lignin with CoNi2@BTC catalysts without external hydrogen. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 303, 140496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Yu, L.; Yang, S.; Cao, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, Z.; Shi, H.; Ma, Q. Insights into the chemical structure and antioxidant activity of lignin extracted from bamboo by acidic deep eutectic solvents. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 40956–40969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passoni, V.; Scarica, C.; Levi, M.; Turri, S.; Griffini, G. Fractionation of industrial softwood kraft lignin: Solvent selection as a tool for tailored material properties. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, M.; Jiao, L.; Dai, H. Molecular weight distribution and dissolution behavior of lignin in alkaline solutions. Polymers 2021, 13, 4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, H.; Li, B.; Udin, S.M.; Maarof, H.; Zhou, W.; Cheng, F.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Alias, H.; et al. Mechanistic insights into the lignin dissolution behavior in amino acid based deep eutectic solvents. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Protasio, T.; Lima, M.D.R.; Teixeira, R.A.C.; Rosario, F.S.D.; de Araujo, A.C.C.; de Assis, M.R.; Hein, P.R.G.; Trugilho, P.F. Influence of extractives content and lignin quality of eucalyptus wood in the mass balance of pyrolysis process. Bioenergy Res. 2021, 14, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jin, X.; Shen, X.; Liu, H.; Tong, R.; Qiu, X.; Xu, J. Study on the relationship between the structure and pyrolysis characteristics of lignin isolated from eucalyptus, pine, and rice straw through the use of deep eutectic solvent. Molecules 2024, 29, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elewa, N.N.; Mabied, A.F. Crystallographic and DFT study of novel dimethoxybenzene derivatives. BMC Chem. 2025, 19, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shao, P.; Geng, W.; Lei, P.; Dong, J.; Chi, Y.; Hu, C. Highly efficient oxidative cleavage of lignin β-O-4 linkages via synergistic Co-CoOx/N-doped carbon and recyclable hexaniobate catalysis. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chmely, S.C.; Nimos, M.R.; Bomble, Y.J.; Foust, T.D.; Paton, R.S.; Beckham, G.T. Computational study of bond dissociation enthalpies for a large range of native and modified lignins. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2011, 2, 2846–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; An, J.; Wang, F. Transformations of biomass, its derivatives, and downstream chemicals over ceria catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 8788–8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Wang, Z.; Wu, R.J.; Bhan, A. Selective vapor-phase hydrodeoxygenation of anisole to benzene on molybdenum carbide catalysts. J. Catal. 2014, 319, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, N.; Usuki, T. Can heteroarenes/arenes be hydrogenated over catalytic Pd/C under ambient conditions? Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 5514–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.; Simon, D.; Sautet, P. Intermediates in the hydrogenation of benzene to cyclohexene on pt (111) and pd (111): A comparison from DFT calculations. Surf. Sci. 2006, 600, 1339–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawi, M.; Paul, J.; Cristol, S.; Payen, E. Guaiacol derivatives and inhibiting species adsorption over MoS 2 and CoMoS catalysts under HDO conditions: A DFT study. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Rousseau, R.; Weber, R.S.; Mei, D.; Lercher, J.A. First-principles study of phenol hydrogenation on Pt and Ni catalysts in aqueous phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10287–10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pintos, D.; Voss, J.; Jensen, A.D.; Studt, F. Hydrodeoxygenation of phenol to benzene and cyclohexane on Rh (111) and Rh (211) surfaces: Insights from density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 18529–18537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Vila, G.; Salvador, P. Capturing electronic substituent effect with effective atomic orbitals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 10482–10491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, D.A.; Dilabio, G.A.; Mulder, P.; Ingold, K.U. Bond strengths of toluenes, anilines, and phenols: to Hammett or not. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez-Grez, R.; Pino-Rios, R. Evaluation of slight changes in aromaticity through electronic and density functional reactivity theory-based descriptors. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21939–21945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chai, X.; Liu, M.; Deng, Y. Novel method for the determination of the methoxyl content in lignin by headspace gas chromatography. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2012, 60, 5307–5310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Clark, J.H.; Budarin, V.L.; Hu, C.; Wu, K.C.; Zhang, S. Microwave-assisted depolymerization of various types of waste lignins over two-dimensional CuO/BCN catalysts. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Xue, B.; Xu, F.; Sun, R. Unveiling the structural heterogeneity of bamboo lignin by in situ HSQC NMR technique. Bioenergy Res. 2012, 5, 886–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lignin | S/G/H a | S/G | β-O-4 b | β-β b | β-5 b | Methoxyl (mmol/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL | 35/49/16 | 0.71 | 89.8 | trace | 10.2 | 11.5 |

| PML | -/99/- | - | 72.9 | 17.0 | 20.1 | 13.3 |

| EL | 76/24/- | 3.22 | 65.3 | 34.7 | trace | 15.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lv, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, K.; Liu, Y.; Ye, X.; Song, L.; Lin, C.; Yang, G.; Liu, M. Insights into Real Lignin Refining: Impacts of Multiple Ether Bonds on the Cracking of β-O-4 Linkages and Selectivity of Products. Molecules 2026, 31, 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010133

Lv Y, Lin X, Yang K, Liu Y, Ye X, Song L, Lin C, Yang G, Liu M. Insights into Real Lignin Refining: Impacts of Multiple Ether Bonds on the Cracking of β-O-4 Linkages and Selectivity of Products. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):133. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010133

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Yuancai, Xuepeng Lin, Kai Yang, Yifan Liu, Xiaoxia Ye, Liang Song, Chunxiang Lin, Guifang Yang, and Minghua Liu. 2026. "Insights into Real Lignin Refining: Impacts of Multiple Ether Bonds on the Cracking of β-O-4 Linkages and Selectivity of Products" Molecules 31, no. 1: 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010133

APA StyleLv, Y., Lin, X., Yang, K., Liu, Y., Ye, X., Song, L., Lin, C., Yang, G., & Liu, M. (2026). Insights into Real Lignin Refining: Impacts of Multiple Ether Bonds on the Cracking of β-O-4 Linkages and Selectivity of Products. Molecules, 31(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010133