Enhanced Microbial Diversity Attained Under Short Retention and High Organic Loading Conditions Promotes High Volatile Fatty Acid Production Efficiency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

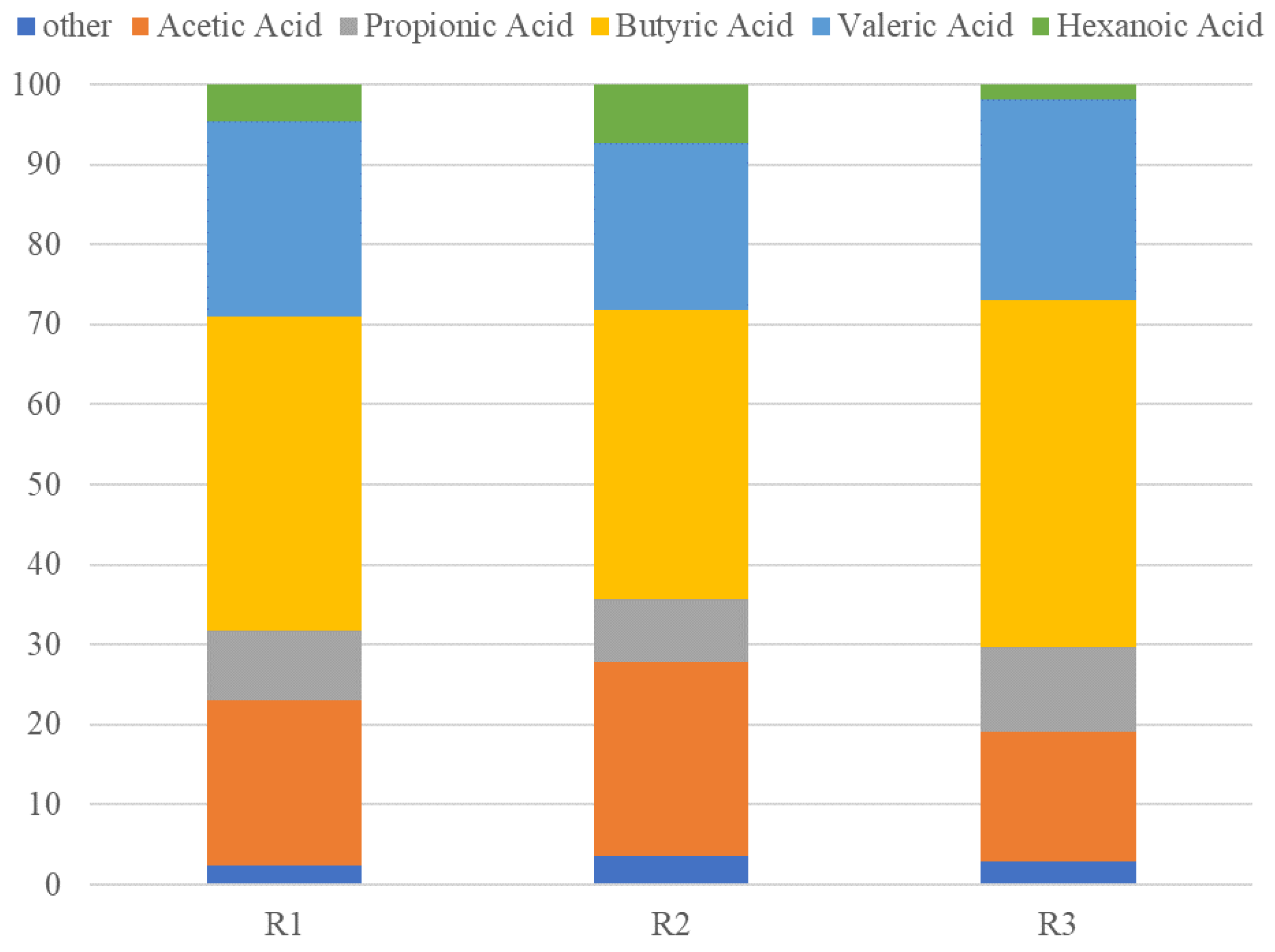

2.1. Fermentation Robustness upon Operational Changes When Targeting at VFAs Production

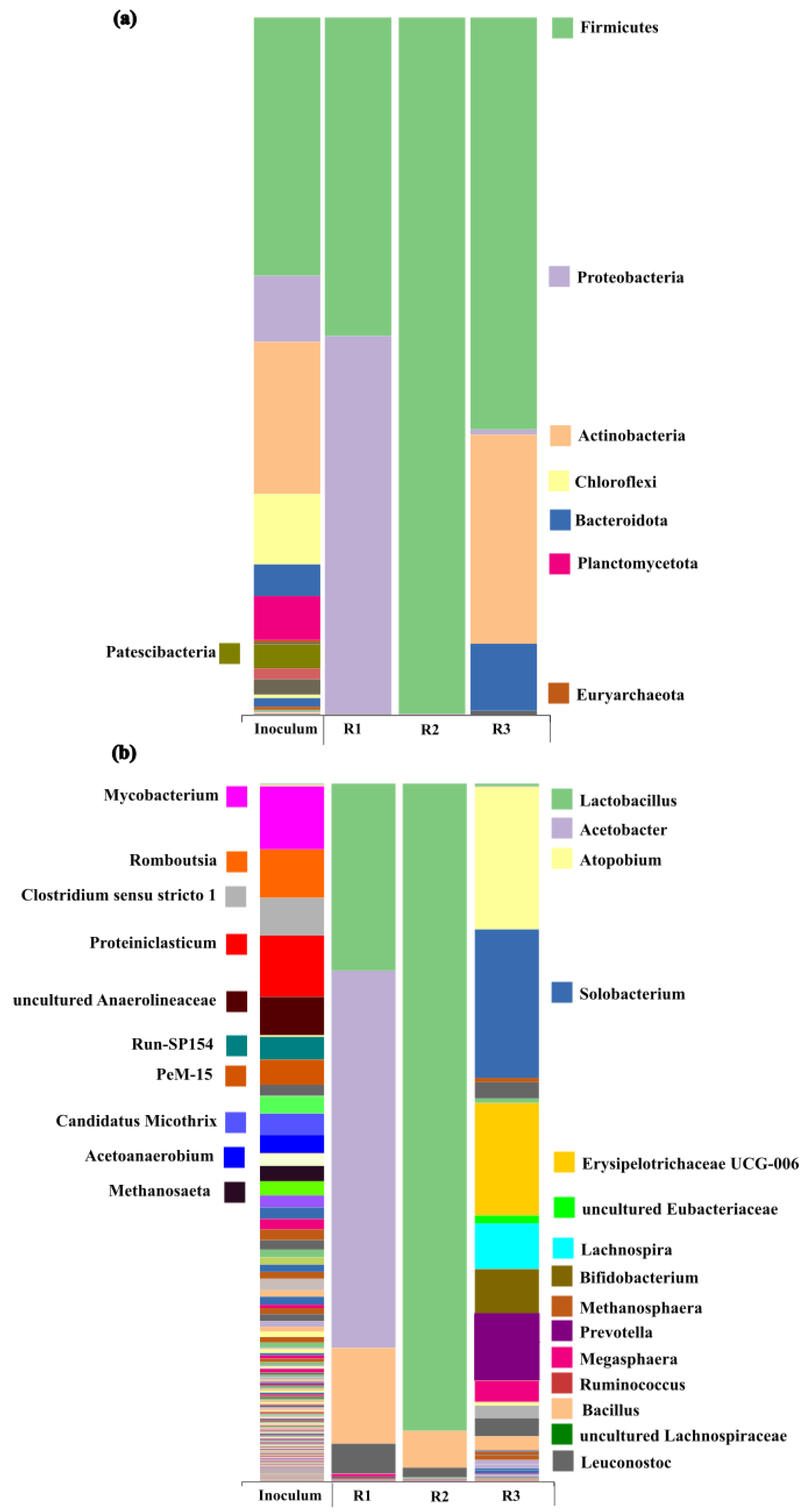

2.2. Microbial Community Changes upon Implemented Operational Conditions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Inoculum and Substrate

3.2. Anaerobic Fermentation

3.3. Process Monitoring

3.4. Microbial Community Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Environment Programme. Food Waste Index Report 2021; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; ISBN 978-92-807-3851-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cavinato, C.; Da Ros, C.; Pavan, P.; Bolzonella, D. Influence of temperature and hydraulic retention on the production of volatile fatty acids during anaerobic fermentation of cow manure and maize silage. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llamas, M.; Greses, S.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; González-Fernández, C. Carboxylic acids production via anaerobic fermentation: Microbial communities’ responses to stepwise and direct hydraulic retention time decrease. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 344, 126282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Howard, S.; Zhu, L. The Response of the Gut Microbiota to Dietary Changes in the First Two Years of Life. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolzonella, D.; Battista, F.; Cavinato, C.; Gottardo, M.; Micolucci, F.; Lyberatos, G.; Pavan, P. Recent developments in biohythane production from household food wastes: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 257, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.J.; González-Fernández, C.; Greses, S. Long hydraulic retention time mediates stable volatile fatty acids production against slight pH oscillations. Waste Manag. 2024, 176, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greses, S.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; Gonzalez-Fernandez, C. Assessing the relevance of acidic pH on primary intermediate compounds when targeting at carboxylate accumulation. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2022, 12, 4519–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiatkiewicz, J.; Slezak, R.; Krzystek, L.; Ledakowicz, S. Production of volatile fatty acids in a semi-continuous dark fermentation of kitchen waste: Impact of organic loading rate and hydraulic retention time. Energies 2021, 14, 2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ras, M.; Lardon, L.; Sialve, B.; Bernet, N.; Steyer, J.P. Experimental study on a coupled process of production and anaerobic digestion of Chlorella vulgaris. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Páez, E.; Serrano, A.; Purswani, J.; Trujillo-Reyes, A.; Fernández-Prior, A.; Fermoso, F.G. Impact of hydraulic retention time on the production of volatile fatty acids from lignocellulosic feedstock by acidogenic fermentation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, M.; Cetecioglu, Z. The effects of pH on the production of volatile fatty acids and microbial dynamics in long-term reactor operation. J. Environ. Managem. 2022, 319, 115700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greses, S.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; González-Fernández, C. Agroindustrial waste as a resource for volatile fatty acids production via anaerobic fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 297, 122486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazzera, G.; Battista, F.; Herrero Garcia, N.; Frison, N.; Bolzonella, D. Volatile fatty acids production from food wastes for biorefinery platforms: A review. J. Environ. Managem. 2018, 226, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, E.I.; Parameswaran, P.; Kang, M.; Canul-Chan, R.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Anaerobic digestion and co-digestion processes of vegetable and fruit residues: Process and microbial ecology. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 9447–9455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdy, A.; Mendez, L.; Blanco, S.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernández, C. Protease cell wall degradation of Chlorella vulgaris: Effect on methane production. Biores. Technol. 2014, 171, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaji, I.; Dionisi, D. Acidogenic fermentation of vegetable and salad waste for chemicals production: Effect of pH buffer and retention time. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5933–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, J.A.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; Ballesteros, M.; González-Fernandez, C. Volatile fatty acids production from protease pretreated Chlorella biomass via anaerobic digestion. Biotech. Progress 2018, 34, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.R.; Khalid, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, L.; Chen, W.; Duan, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Li, D. Microbial community dynamics and volatile fatty acid production during anaerobic digestion of microaerated food waste under different organic loadings. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 27, 101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, J.; Guivernau, M.; Fernández, B.; Vila, J.; Viñas, M.; Riau, V.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Functional biodiversity and plasticity of methanogenic biomass from a full-scale mesophilic anaerobic digester treating nitrogen-rich agricultural wastes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, C.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Larsson, M.; Alm, E.; Yekta, S.S.; Svensson, B.H.; Sørensen, S.J.; Karlsson, A. 454 pyrosequencing analyses of bacterial and archaeal richness in 21 full-scale biogas digesters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 85, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, E.; Sun, X.; Ellis, P.R.; Taylor, M.; Guo, M. Temporal dynamics of microbial communities in anaerobic digestion: Influence of temperature and feedstock composition on reactor performance and stability. Water Res. 2025, 284, 123974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, M.; Mou, H.; An, Z.; Fu, H.; Su, X. Comparation of mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and waste activated sludge driven by biochar derived from kitchen waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegand, S.; Jogler, M.; Boedeker, C.; Pinto, D.; Vollmers, J.; Rivas-Marín, E.; Kohn, T.; Peeters, S.H.; Heuer, A.; Rast, P.; et al. Cultivation and functional characterization of 79 Planctomycetes uncovers their unique biology. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanaro, S.; Treu, L.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Kovalovszki, A.; Ziels, R.M.; Maus, I.; Zhu, X.; Kougias, P.G.; Basile, A.; Luo, G.; et al. New insights from the biogas microbiome by comprehensive genome-resolved metagenomics of nearly 1600 species originating from multiple anaerobic digesters. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2020, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, D.; Lage, O.M.; Calusinska, M. Phylogenetic diversity and community structure of Planctomycetota from plant biomass-rich environments. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1579219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lera, M.; Ferrer, J.F.; Borrás, L.; Martí, N.; Serralta, J. Mesophilic anaerobic digestion of mixed sludge in CSTR and AnMBR systems: A perspective on microplastics fate. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaballah, E.S.; Gao, L.; Shalaby, E.A.; Yang, B.; Sobhi, M.; Ali, M.M.; Samer, M.; Tang, C.; Zhu, G. Performance and mechanism of a novel hydrolytic bacteria pretreatment to boost waste activated sludge disintegration and volatile fatty acids production during acidogenic fermentation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 376, 124399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greses, S.; Tomás-Pejó, E.; González-Fernández, C. Short-chain fatty acids and hydrogen production in one single anaerobic fermentation stage using carbohydrate-rich food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Kang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Du, M. Short chain fatty acids accumulation and microbial community succession during ultrasonic-pretreated sludge anaerobic fermentation process: Effect of alkaline adjustment. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2014, 94, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Hou, W.; Bian, C.; Zheng, T.; Xiao, B.; Li, L. Enhancing anaerobic digestion of swine manure using microbial electrolysis cell and microaeration. Chem. Eng. J 2025, 514, 163319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, P. Enhanced volatile fatty acid production from anaerobic fermentation of waste activated sludge by combined sodium citrate and heat pretreatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampio, E.A.; Blasco, L.; Vainio, M.M.; Kahala, M.M.; Rasi, S.E. Volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and methane from food waste and cow slurry: Comparison of biogas and VFA fermentation processes. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detman, A.; Laubitz, D.; Chojnacka, A.; Kiela, P.R.; Salamon, A.; Barberán, A.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Błaszczyk, M.K.; Sikora, A. Dynamics of dark fermentation microbial communities in the light of lactate and butyrate production. Microbiome 2021, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzioli, F.; Magonara, C.; Mengoli, G.; Bolzonella, D.; Battista, F. Production, purification and recovery of caproic acid, Volatile fatty acids and methane from Opuntia ficus indica. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 190, 114083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, F.; Xia, X.; Fang, S.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, A.; Feng, L.; Wang, D.; Luo, J. Tannic acid modulation of substrate utilization, microbial community, and metabolic traits in sludge anaerobic fermentation for volatile fatty acid promotion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 9792–9803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DusÏkova, D.; Marounek, M. Fermentation of pectin and glucose, and activity of pectin-degrading enzymes in the rumen bacterium Lachnospira multiparus. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 33, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.A.D.; da Silva, E.M.; de Oliveira, D.C.P.; Magnus, B.S.; Motteran, F.; Florencio, L.; Leite, W.R.M. Volatile fatty acid and methane production from vinasse and microalgae using two-stage anaerobic co-digestion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 16780–16792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APHA; AWWA; WEF. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 23rd ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0875532875. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, F.; Tomé, D.; Mirand, P.P. Converting Nitrogen into Protein—Beyond 6.25 and Jones’ Factors. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 48, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reactor | R1 | R2 | R3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 5.1 ± 0.1 |

| HRT (d) | 14 | 14 | 11 |

| OLR (g COD/Ld) | 3.3 | 3.3 | 4.1 |

| TCOD (g/L) | 43.3 ± 2.4 | 36.5 ± 2.9 | 37.1 ± 4.6 |

| SCOD/TCOD (%) | 65.4 ± 4.0 | 71.2 ± 5.6 | 63.8 ± 4.4 |

| TS (g/L) | 23.2 ± 0.2 | 26.8 ± 0.6 | 20.2 ± 4.6 |

| VS/TS (%) | 61.7 ± 1.2 | 59.4 ± 1.7 | 68.9 ± 2.2 |

| VFAs (g/L) | 15.9 ± 1.4 | 13.7 ± 2.4 | 11.7 ± 1.4 |

| VFAs (g COD/L) | 24.8 ± 2.5 | 21.0 ± 3.9 | 19.6 ± 1.9 |

| g VFAs/Ld | 1.13 ± 0.1 | 1.00 ± 0.2 | 1.05 ± 0.1 |

| Bioconversion (%) | 53.6 ± 5.4 | 45.4 ± 8.5 | 43.7 ± 4.5 |

| Acidification (%) | 87.7 ± 9.7 | 80.5 ± 13.1 | 83.7 ± 10.3 |

| VS removal (%) | 53.2 ± 1.3 | 47.9 ± 0.5 | 60.1 ± 3.2 |

| Sample | Observed OTUs | Shannon Index |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculum | 477 | 4.09 |

| R1-pH 5- HRT 14 d- OLR 3.3 g COD/Ld | 53 | 1.17 |

| R2-pH 6- HRT 14 d- OLR 3.3 g COD/Ld | 53 | 0.34 |

| R3-pH 5- HRT 11 d- OLR 4.1 g COD/Ld | 103 | 2.37 |

| Carrot Residue Pulp | |

|---|---|

| SCOD/TCOD | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| TS (g/L) | 42.7 ± 0.3 |

| VS/TS | 0.8 ± 0.1 |

| TKN (g N/L) | 0.4 ± 0.0 |

| Carbohydrates (w/w %) | 66.1 ± 0.0 |

| Proteins (w/w %) | 7.4 ± 1.4 |

| Lipids (w/w %) | 16.3 ± 4.0 |

| Ash (w/w %) | 10.0 ± 2.6 |

| pH (25 °C) | 5.8 ± 0.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chao-Reyes, C.; Timmers, R.A.; Mahdy, A.; Greses, S.; González-Fernández, C. Enhanced Microbial Diversity Attained Under Short Retention and High Organic Loading Conditions Promotes High Volatile Fatty Acid Production Efficiency. Molecules 2026, 31, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010132

Chao-Reyes C, Timmers RA, Mahdy A, Greses S, González-Fernández C. Enhanced Microbial Diversity Attained Under Short Retention and High Organic Loading Conditions Promotes High Volatile Fatty Acid Production Efficiency. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleChao-Reyes, Claudia, Rudolphus Antonius Timmers, Ahmed Mahdy, Silvia Greses, and Cristina González-Fernández. 2026. "Enhanced Microbial Diversity Attained Under Short Retention and High Organic Loading Conditions Promotes High Volatile Fatty Acid Production Efficiency" Molecules 31, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010132

APA StyleChao-Reyes, C., Timmers, R. A., Mahdy, A., Greses, S., & González-Fernández, C. (2026). Enhanced Microbial Diversity Attained Under Short Retention and High Organic Loading Conditions Promotes High Volatile Fatty Acid Production Efficiency. Molecules, 31(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010132