Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells into Catechols via Tandem Metal Triflate and Pd/C Catalysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Composition of Castor Shells

2.2. Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells to Aromatics over the Pd/C + Lewis Acid Systems

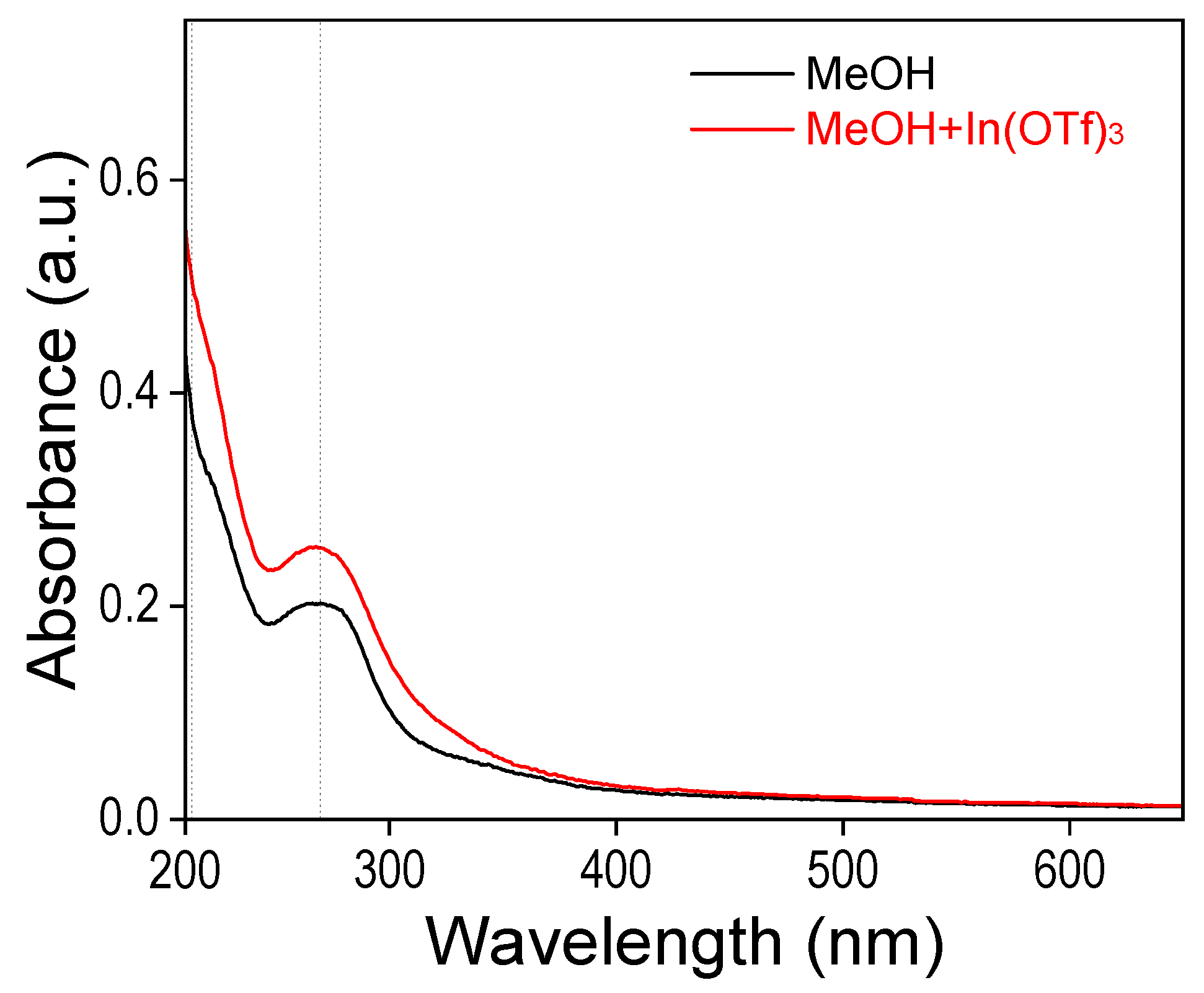

2.3. The Mechanism of In3+ on the Pd/C-Mediated Cα/β–OAr Bonds Reductive Cleavage and C-Lignin In Situ Release

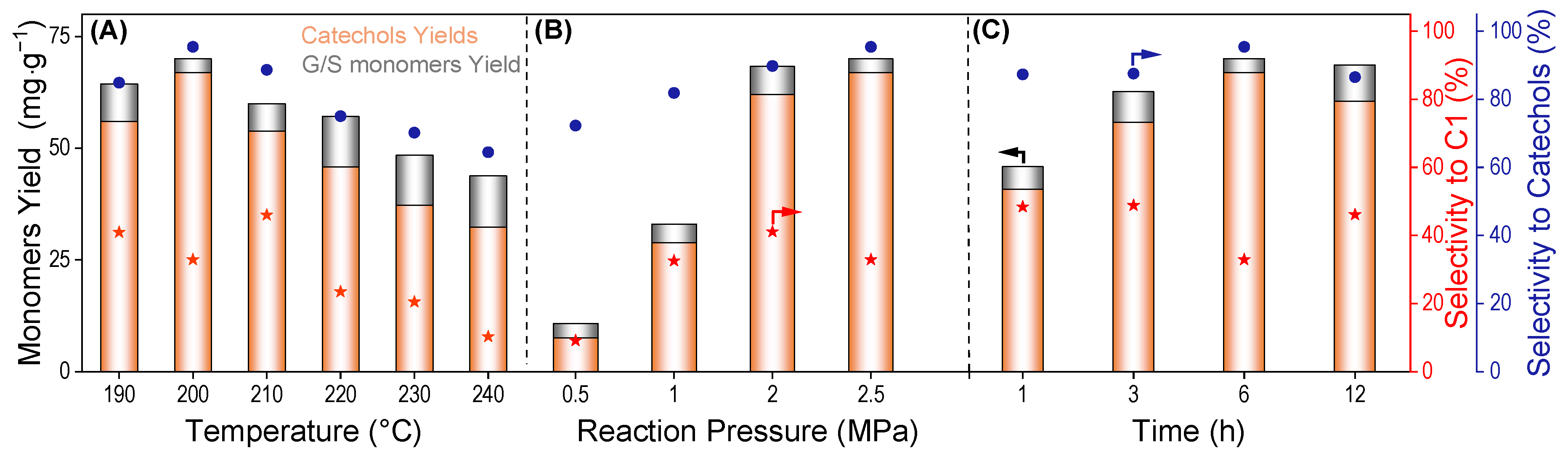

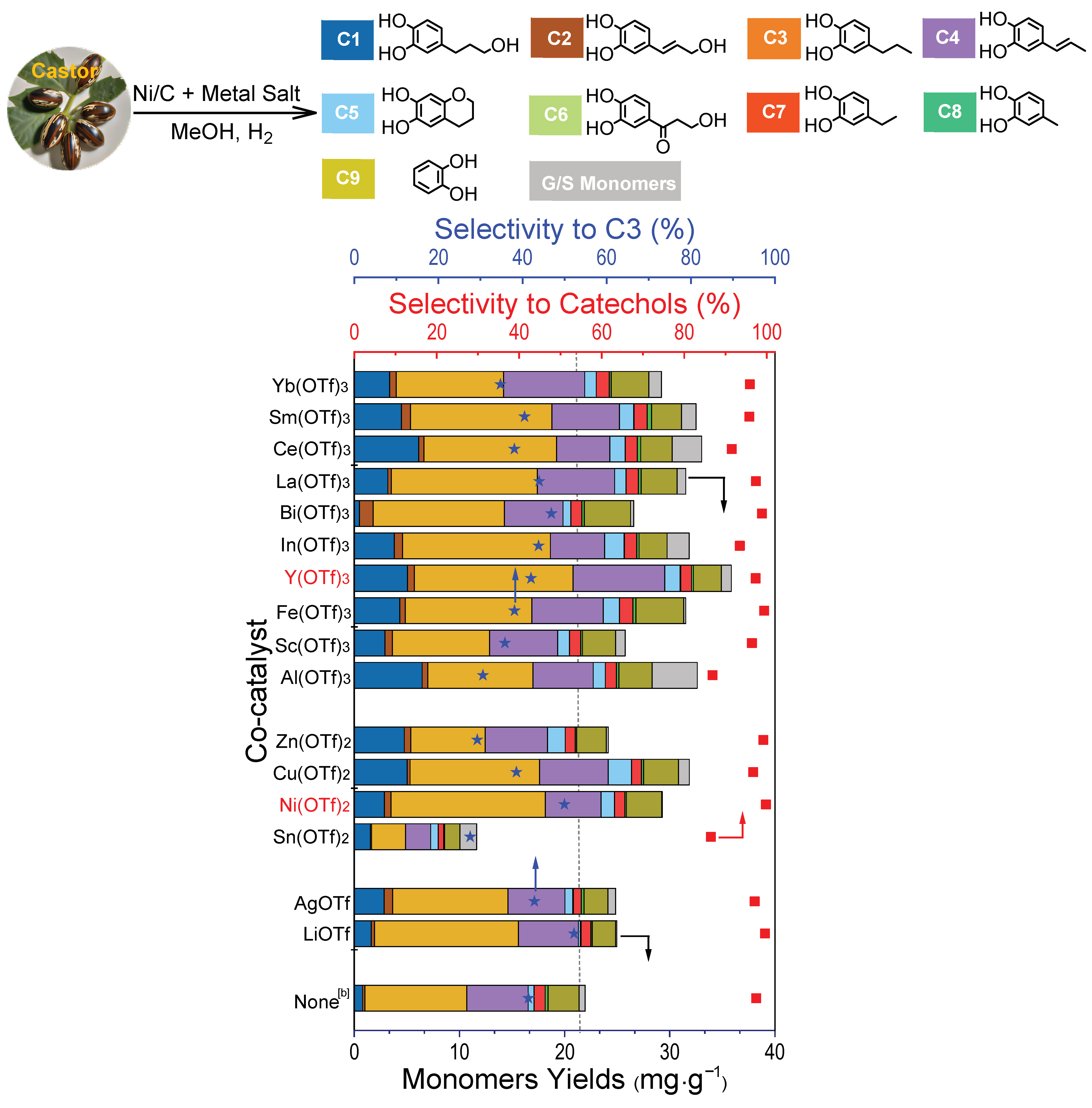

2.4. Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells to Aromatics over the Ni/C + Lewis Acid Systems

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials, Chemicals, and Catalysts

3.2. Procedure for Catalytic Hydrogenolysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Wang, A.; Huber, G.W.; Zhang, T. Catalytic Transformation of Lignin for the Production of Chemicals and Fuels. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 11559–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fridrich, B.; de Santi, A.; Elangovan, S.; Barta, K. Bright side of lignin depolymerization: Toward new platform chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 614–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.F.; Shen, X.J.; Jin, Y.C.; Cheng, J.L.; Cai, C.; Wang, F. Catalytic Strategies and Mechanism Analysis Orbiting the Center of Critical Intermediates in Lignin Depolymerization. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 4510–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.F.; Wang, F. Lignin Conversion Catalysis: Transformation to Aromatic Chemicals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Dong, L.; Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Chemicals from Lignin: A Review of Catalytic Conversion Involving Hydrogen. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4181–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Omar, M.M.; Barta, K.; Beckham, G.T.; Luterbacher, J.S.; Ralph, J.; Rinaldi, R.; Roman-Leshkov, Y.; Samec, J.S.M.; Sels, B.F.; Wang, F. Guidelines for performing lignin-first biorefining. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 262–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, R. Plant Biomass Fractionation Meets Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8559–8560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Xin, Y.; Liu, H.; Han, B. Product-oriented Direct Cleavage of Chemical Linkages in Lignin. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4367–4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.F.; Wang, F. Catalytic Lignin Depolymerization to Aromatic Chemicals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, F. Catalytic Cleavage of Lignin C–O and C–C Bonds. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Ford, P.C., van Eldik, R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 77, pp. 175–218. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Zhong, R.; Makshina, E.; d’Halluin, M.; van Limbergen, Y.; Verboekend, D.; Sels, B.F. Propylphenol to Phenol and Propylene over Acidic Zeolites: Role of Shape Selectivity and Presence of Steam. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 7861–7878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Lu, L.; Lv, W.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Ma, L.; et al. Oxidative Catalytic Fractionation of Lignocellulose to High-Yield Aromatic Aldehyde Monomers and Pure Cellulose. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 7929–7941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, Q.; Yang, H.; Su, W.; He, H.; Tian, S.; Li, C.; Zhang, T. Tungsten-based catalysts for lignin conversion: A review. Catal. Today 2024, 442, 114913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chen, D. Direct conversion of lignin to liquid hydrocarbons for sustainable biomass valorization. Catal. Today 2024, 441, 114882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Amiri, M.T.; Questell-Santiago, Y.M.; Héroguel, F.; Li, Y.; Kim, H.; Meilan, R.; Chapple, C.; Ralph, J.; Luterbacher, J.S. Formaldehyde stabilization facilitates lignin monomer production during biomass depolymerization. Science 2016, 354, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.F.; Li, H.J.; Lu, J.M.; Zhang, X.C.; MacArthur, K.E.; Heggen, M.; Wang, F. Promoting Lignin Depolymerization and Restraining the Condensation via an Oxidation-Hydrogenation Strategy. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3419–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Jiang, B.; Li, Z.; Jiang, F.; Cheng, J.; Liu, J.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, C. Protolignin Catalytic Depolymerization to Aromatic Chemicals via an Oxidation–Isolation–Hydrogenation Strategy. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 5764–5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, X.; Li, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, F. Photothermal catalytic transfer hydrogenolysis of protolignin. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.L.; Rao, X.L.; Azad, R.; Pandey, R.; Xiao, X.R.; Harkelroad, A.; Wang, X.Q.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A. Enzymatic basis for C-lignin monomer biosynthesis in the seed coat of Cleome hassleriana. Plant J. 2019, 99, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Havkin-Frenkel, D.; Dixon, R.A.; Ralph, J. A polymer of caffeyl alcohol in plant seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1772–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Jackson, L.; Nakashima, J.; Ralph, J.; Dixon, R.A. Novel seed coat lignins in the Cactaceae: Structure, distribution and implications for the evolution of lignin diversity. Plant J. 2013, 73, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shuai, L.; Kim, H.; Motagamwala, A.H.; Mobley, J.K.; Yue, F.; Tobimatsu, Y.; Havkin-Frenkel, D.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A.; et al. An “Ideal Lignin” Facilitates Full Biomass Utilization. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobimatsu, Y.; Chen, F.; Nakashima, J.; Escamilla-Trevino, L.L.; Jackson, L.; Dixon, R.A.; Ralph, J. Coexistence but Independent Biosynthesis of Catechyl and Guaiacyl/Syringyl Lignin Polymers in Seed Coats. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 2587–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wen, J.; Zhang, J.; Ji, Y.; Hou, G.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yuan, T.-Q.; Wang, F. Standardization transformation of C-lignin to catechol and propylene. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Qi, W.; He, Z.; Yan, N. One-pot production of phenazine from lignin-derived catechol. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.; Chen, C. Catechol-Functionalized Polyolefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 7953–7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Du, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Song, G. Sustainable Production of Bioactive Molecules from C-Lignin-Derived Propenylcatechol. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liao, Y.; Bomon, J.; Tian, G.; Bai, S.T.; Van Aelst, K.; Zhang, Q.; Vermandel, W.; Wambacq, B.; Maes, B.U.W.; et al. Lignin-First Monomers to Catechol: Rational Cleavage of C-O and C-C Bonds over Zeolites. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.-M.; Meng, X.; Pu, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Ragauskas, A.J.J. Bioconversion of Homogeneous Linear C-Lignin to Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biomacromolecules 2023, 24, 3996–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Hu, B.; Shen, Q.; Su, S.; Wang, S.; Song, G. Creating tough Mussel-Inspired underwater adhesives from plant catechyl lignin. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 482, 148828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, T.; Xiao, L.P.; Zou, S.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, C.-H.; Sun, R.-C. Tough and biodegradable C-lignin cross-linked polyvinyl alcohol supramolecular composite films with closed-looping recyclability. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Shen, Q.; Su, S.; Lin, J.; Song, G. The temptation from homogeneous linear catechyl lignin. Trends Chem. 2022, 4, 948–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Xie, H.; Ye, D.; Zhang, J.; Huang, K.; Liao, B.; Chen, J. Sustainable production of catechol derivatives from waste tung nutshell C/G-type lignin via heterogeneous Cu-NC catalytic oxidation. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 5069–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Meng, R.; Cai, T.; Pu, Y.; Zhao, Z.-M.; Ragauskas, A.J.J. Valorization of homogeneous linear catechyl lignin: Opportunities and challenges. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 12750–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Shen, Q.; Wang, S.; Song, G. Discovery, disassembly, depolymerization and derivatization of catechyl lignin in Chinese tallow seed coats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 239, 124256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Su, S.; Song, G. Lignin Extracted from Various Parts of Castor (Ricinus communis L.) Plant: Structural Characterization and Catalytic Depolymerization. Polymers 2023, 15, 2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhu, G.; Ye, D.; Cai, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, K.; Mai, Y.; Liao, B.; Chen, J. Catalytic oxidative conversion of C/G-type lignin coexisting in Tung nutshells to aromatic aldehydes and acids. New J. Chem. 2023, 47, 17072–17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, C.; Wang, X.; Shrestha, H.K.; Abraham, P.E.; Hettich, R.L.; Chen, F.; Barros, J.; Dixon, R.A. Major facilitator family transporters specifically enhance caffeyl alcohol uptake during C-lignin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2024, 246, 1520–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, M.L.; Anderson, E.M.; Meek, K.M.; Reed, M.; Katahira, R.; Chen, F.; Dixon, R.A.; Beckham, G.T.; Roman-Leshkoy, Y. Reductive Catalytic Fractionation of C-Lignin. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 11211–11218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.; Xiao, L.-P.; Song, G. Selective hydrogenolysis of catechyl lignin into propenylcatechol over an atomically dispersed ruthenium catalyst. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Song, G. Catalytic hydrogenolysis of castor seeds C-lignin in deep eutectic solvents. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 169, 113666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, B.; Li, Z.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, B.; Shen, X.; Jin, Y. Catalytic hydrogenative depolymerization of castor shells C-lignin to catechols over the mixed Pd/C + Pd(OH)2/C System. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 228, 120913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Z.; Su, S.H.; Xiao, L.P.; Wang, B.; Sun, R.C.; Song, G.Y. Catechyl Lignin Extracted from Castor Seed Coats Using Deep Eutectic Solvents: Characterization and Depolymerization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7031–7038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.Z.; Zou, S.L.; Xiao, L.P.; Sun, R.C. Catechyl lignin extracted from candlenut by biphasic 2-methyltetrahydro-furan/water: Characterization and depolymerization. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 288, 119828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, L. Disassembly of catechyl lignin from castor shells by maleic acid aqueous and production of single catechols. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 222, 119974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Cui, C.; Shao, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Zhao, D.; Xu, F. Efficient separation of catechyl lignin from castor seed coats via molten salt hydrate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.M.; Gonzalez, O.M.M.; Zhu, J.D.; Koranyi, T.I.; Boot, M.D.; Hensen, E.J.M. Reductive fractionation of woody biomass into lignin monomers and cellulose by tandem metal triflate and Pd/C catalysis. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, T.L.; Li, Z.; Marks, T.J. Thermodynamic Strategies for C−O Bond Formation and Cleavage via Tandem Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Cao, F.-s.; Wang, S.; Shen, Q.; Luo, G.; Lu, Q.; Song, G. Organoborane-catalysed reductive depolymerisation of catechyl lignin under ambient conditions. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 8172–8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvenatam, B.; Heeres, E.H.J.; Pidko, E.A.; Hensen, E.J.M. Lewis-acid catalyzed depolymerization of Protobind lignin in supercritical water and ethanol. Catal. Today 2016, 259, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuss, P.J.; Scott, M.; Tran, F.; Westwood, N.J.; de Vries, J.G.; Barta, K. Aromatic monomers by in situ conversion of reactive intermediates in the acid-catalyzed depolymerization of lignin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7456–7467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wang, S.; Song, G. Disassembling catechyl and guaiacyl/syringyl lignins coexisting in Euphorbiaceae seed coats. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 7235–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xu, H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, K.; Jiang, J. Unveiling the Multifaceted Roles of CeO2-Based Catalysts for Lignin Depolymerization: Beyond a Mere Support. ChemCatchem 2025, 2025, e01169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, B.; Jin, W.; Zhang, H. Enhanced Targeted Deoxygenation Catalytic Pyrolysis of Lignin to Aromatic Hydrocarbons over Oxygen Vacancies Pt-MoOx/TiO2. ChemCatchem 2025, 17, e202401727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, I.; Marcum, C.; Kenttamaaa, H.; Abu-Omar, M.M. Mechanistic investigation of the Zn/Pd/C catalyzed cleavage and hydrodeoxygenation of lignin. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Wang, F.; Cai, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Xu, J. Lignin depolymerization (LDP) in alcohol over nickel-based catalysts via a fragmentation-hydrogenolysis process. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 994–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfour, W.J. The 275-nm Absorption System of Anisole. I. Mol. Spectrosc. 1985, 109, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, B.; Xu, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; Cui, Q.; Yue, Y. Hydrodepolymerization of lignin with Ni supported on active carbon catalysts reduced at different temperatures. Catal. Commun. 2024, 186, 106826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. Ethanolysis of enzymatic hydrolysis lignin with Ni catalysts on different supports: The roles of catalytic sites. Catal. Today 2024, 438, 114750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; Yu, W.; Wang, F.; Xu, J. Hydrogenation and cleavage of the C-O bonds in the lignin model compound phenethyl phenyl ether over a nickel-based catalyst. Chin. J. Catal. 2013, 34, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Substrate | Catalyst | Conversion (%) | Products Distribution (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 2-PPE | ||||

| 1 | BPE a | In(OTf)3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | BPE a | Pd/C | 51.5 | 24.0 | 26.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | BPE a | Pd/C + In(OTf)3 | 81.5 | 35.5 | 46.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | 2-PPE b | In(OTf)3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | 2-PPE b | Pd/C | 63.1 | 11.9 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 15.2 | 25.6 | 4.4 | - |

| 6 | 2-PPE b | Pd/C + In(OTf)3 | 89.8 | 15.7 | 12.1 | 4.3 | 20.5 | 31.5 | 5.6 | - |

| 7 | PBOD c | In(OTf)3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | PBOD c | Pd/C | 54.1 | - | 46.8 | - | 3.1 | - | - | 49.3 |

| 9 | PBOD c | Pd/C + In(OTf)3 | 81.6 | - | 74.4 | - | 4.1 | - | - | 71.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, J.; Zheng, W.; Li, H.; Jiang, F.; Cheng, J.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C. Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells into Catechols via Tandem Metal Triflate and Pd/C Catalysis. Molecules 2026, 31, 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010120

Hu J, Zheng W, Li H, Jiang F, Cheng J, Jiang B, Zhang T, Zhang C. Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells into Catechols via Tandem Metal Triflate and Pd/C Catalysis. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):120. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010120

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Jianan, Weimin Zheng, Hao Li, Fuzhong Jiang, Jinlan Cheng, Bo Jiang, Tingwei Zhang, and Chaofeng Zhang. 2026. "Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells into Catechols via Tandem Metal Triflate and Pd/C Catalysis" Molecules 31, no. 1: 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010120

APA StyleHu, J., Zheng, W., Li, H., Jiang, F., Cheng, J., Jiang, B., Zhang, T., & Zhang, C. (2026). Catalytic Reductive Fractionation of Castor Shells into Catechols via Tandem Metal Triflate and Pd/C Catalysis. Molecules, 31(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010120