Abstract

Organic phase change materials (OPCMs) show immense application potential in solar energy storages owing to high energy storage capacity and latent heat efficiency. However, it is difficult to achieve prolonged energy storage due to the sensitivity of phase change to environmental temperature, and adding other substances will lead to a decrease in total energy density. Herein, azobenzene organic phase change composite (C14Azo-MA) was designed and prepared by doping myristic acid (MA) with an azobenzene derivative (C14Azo) featuring a carbon chain identical to that of the MA matrix. C14Azo-MA was systematically characterized by UV–Visible absorption spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry. The results showed that the C14Azo-MA retains the same isomerization properties as the C14Azo dopant. C14Azo-MA, due to its molecular photoisomerization and enhanced intermolecular interactions, establishes a new energy barrier and forms supercooling within C14Azo-MA, thereby allowing the storage of thermal energy below the crystallization temperature of MA. Notably, the C14Azo-MA exhibits a high energy density of 225.08 J g−1, surpassing that of pure MA by 14.42%. This work holds significant potential for solar energy storage applications.

1. Introduction

Due to the abundance and wide distribution of solar energy resources, as well as its clean and pollution-free characteristics, the application prospects of solar energy in the fields of renewable energy and clean energy are extremely broad [1,2,3]. In recent years, with the increasing global demand for sustainable energy, the development and utilization of solar energy have been increasingly focused upon by researchers. However, challenges are presented by the intermittent and unstable nature of solar energy, especially in matching energy supply with fluctuating demand across different times and regions [4,5,6]. Therefore, the development of efficient solar energy storage technologies is regarded as essential for achieving rational energy allocation and enhancing the efficiency of its utilization [7,8].

In order to effectively obtain and utilize solar energy, a large number of material systems have been proposed in recent years. These systems range from inorganic binary oxide ceramics (such as TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3) for photovoltaic and related applications [9] to organic photoswitchable molecules (known as molecular solar thermal (MOST)) [10,11] and organic phase change materials (OPCMs) for solar thermal energy storage [12]. Among them, due to their advantages in high energy storage capacity and latent heat efficiency, OPCMs have attracted increasing attention from experts and scholars [13,14,15,16]. OPCMs, classified as alkanes, fatty alcohols and acids, can absorb or release a large amount of thermal energy during the phase transition process, and thus are suitable for extensive applications across a wide range of temperatures [17,18,19], such as cold thermal energy storage [20,21,22], electronics/battery thermal management [23,24,25] and waste heat recovery [26,27,28]. However, traditional OPCMs often face rapid heat loss, reduced energy density lowered by the addition of other substances, and uncontrolled energy release (as the crystallization process is primarily influenced by ambient temperature). These issues severely limit their effectiveness in practical applications like long-duration solar thermal storage, efficient long-range heat transport and responsive on-demand heat delivery, particularly in regions experiencing limited sunlight or significant diurnal temperature swings [1,29,30]. Therefore, eliminating or avoiding the aforementioned issues of OPCMs has become a key focus of current research.

In recent years, the introduction of a new approach based on azobenzene (AZO) photo-switches into OPCMs has garnered increasing research interest, offering controllable and high energy density capabilities [7,31]. AZO, which can be also applied in the fields of liquid crystals [32,33], typically exhibits two distinct conformations: a stable trans-AZO at room temperature and a high-energy metastable cis-AZO. At ambient temperatures, AZO absorbs light energy, such as ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, and undergoes trans→cis photoisomerization, effectively storing energy as the isomerization enthalpy (ΔHiso, the energy difference between the two conformers). When it is integrated into OPCMs, the high-energy cis-AZO produced through trans→cis isomerization can induce photothermal supercooling, usually called photoinduced supercooling, which is characterized by a significant photoinduced crystallization temperature difference (ΔTc). This phenomenon allows OPCMs to remain stable in their liquid phase below the temperature of their intrinsic crystallization point, thereby achieving prolonged energy storage. Subsequently, exposure to visible light or elevated temperature can trigger the cis→trans photoisomerization reaction of high-energy metastable cis-AZO, releasing the stored energy as heat. Therefore, the combined release of the latent heat of OPCMs and the isomerization enthalpy of AZO is precisely controlled by visible light or thermal input, resulting in an increase in the overall energy density.

Han et al. [34,35] introduced AZO molecules into OPCMs for the first time. They demonstrated that the reversible isomerization of AZO groups under light irradiation changed their interactions with OPCMs, thus affecting the crystallization behavior of OPCMs. Their work achieved liquid-phase retention below the crystallization point of the original OPCMs and heat storage at 36 °C for about 10 h. On this basis, other researchers have explored more diverse molecular structure designs to optimize light control performance. Feng et al. [36] and our group [7] developed a series of photo-responsive composite phase change materials. These materials are based on azobenzene (AZO) as the core, grafted with alkyl ether or alkyl ester groups and then compounded with corresponding alkanes or alkanols. The studies have shown that these composites not only achieve an adjustable ΔTc ranging from 3.33 to 8.80 °C, but also enable rapid simultaneous release of latent heat and photothermal energy (207 or 239 J g−1), while offering heat storage capabilities for up to 10 h. Chen et al. [31] systematically studied the light-controlled phase change ability of various grafted azobenzene derivatives on organic phase change materials. Their findings indicated that azobenzenes with altered polarity had a more significant impact on the crystallization behavior of fatty acid-based systems. Our group [8] also investigated the photo-controlled energy storage and thermal release of azobenzene-modified dodecanoic acid phase change composites. The results showed that composites with matching chain lengths exhibited optimal performance, with a tunable ΔTc of 4–12 °C, and a synchronous heat release of 217.72 J g−1 under near-ambient temperature conditions. However, the relatively low energy density remains a limitation in practical applications. Furthermore, there is a scarcity of research specifically focusing on the photo-controlled performance of AZO with matching chain lengths in fatty acid systems.

Herein, we designed and synthesized a novel photo-controlled phase change composite material (C14Azo-MA), comprising myristic acid (MA) and a tailored azobenzene derivative, C14Azo, which possesses a chain length identical to that of MA. Compared with previously reported systems [8], this C14Azo-MA design offers distinct advantages. On the one hand, the extended alkyl chain length introduces stronger intermolecular van der Waals interactions. On the other hand, this strategy leads to superior thermal performance: the C14Azo-MA achieves significantly higher energy densities (up to 225.08 J g−1) and operates at elevated phase transition temperatures suitable for broader thermal management applications. The chemical structure of C14Azo-MA was thoroughly characterized using fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction (XRD). The photo-absorption and photoisomerization properties of C14Azo-MA were investigated by ultraviolet–visible (UV–Vis) spectroscopy. Thermal stability, optically-controlled phase change performance, and energy storage characteristics of C14Azo-MA were assessed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The influence of C14Azo content on energy density and photo-induced supercooling effect were further investigated. Such C14Azo-MA materials open the way for the develop of advanced material for solar thermal storage applications.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemical Composition and Crystallinity

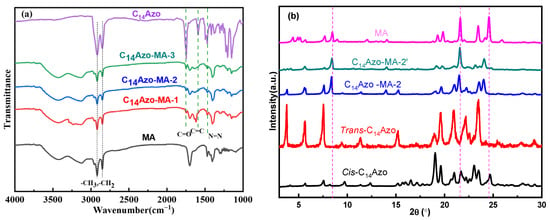

In order to explore the chemical composition of C14Azo-MA, FTIR were conducted. Figure 1a displays the FTIR spectrum of C14Azo-MA, C14Azo and MA, where C14Azo-MA-1, C14Azo-MA-2 and C14Azo-MA-3 correspond to C14Azo mass fractions of 35, 45, and 55 wt% in C14Azo-MA composite, respectively. The FT-IR spectrum of C14Azo-MA includes characteristic peaks of both C14Azo and MA. Specifically, the characteristic peaks at 2918, 2850, and 1746 cm−1 indicate the presence of -CH3, -CH2, and -C=O stretching vibrations. The vibrational bands at 1590~1471 cm−1, and ~1416 cm cm−1 are attributed to the C=C of benzene and -N=N stretching vibrations, respectively. The peak at 1203 cm−1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the ester group. The vibrational band at 1249 cm−1 is ascribed to the bending vibration of -CH2. The characteristic peaks of the C–H bending (syn) and out-of-plane bending vibrations of -CH2- appear at ~1380 cm−1 and ~1226 cm−1, respectively [7]. The above results indicate the successful fabrication of the composite.

Figure 1.

(a) FT-IR spectra and (b) XRD of C14Azo and C14Azo-MA.

Additionally, the crystallinity of the C14Azo-MA (taking the C14Azo mass fractions of 45 wt% as an example) before and after irradiation were investigated by XRD and illustrated in Figure 1b. The non-UV-irradiated sample (C14Azo-MA-2) displayed diffraction peaks associated with MA chains [37,38] and trans-C14Azo [7]. In contrast, the UV-irradiated sample (C14Azo-MA-2′) revealed diffraction peaks corresponding to MA and cis-C14Azo, resulting from photoisomerization. Importantly, the maximum peak in C14Azo-MA-2′ is slightly shifted to a lower diffraction angle compared to the corresponding peak in the C14Azo-MA-2 sample, this is because the increased interlayer spacing of MA leads to weakened intermolecular interactions of MA. Additionally, the diffraction peak is broadened and its intensity reduced, resulting in the inhibition of MA crystallization and ultimately causing supercooling [8,34]. These results suggest that cis-C14Azo has a significant effect on the crystallinity of MA, which aids in extending its energy storage duration.

2.2. Photoisomerization Properties

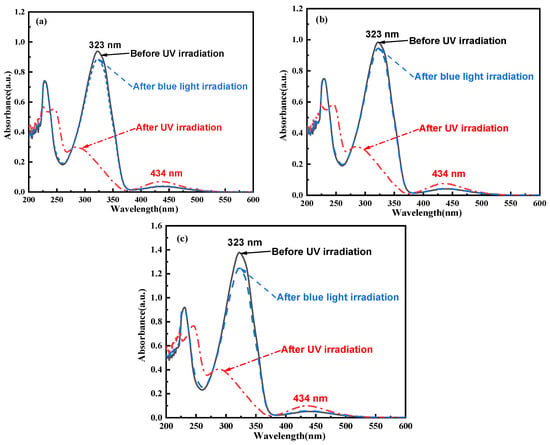

The photoisomerization properties of C14Azo-MA are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. From the Figure 2, it can be seen that all trans-C14Azo-MA have a strong π→π* transition (323 nm) and a weak n→π* transition (434 nm) absorption bands in the range from 250 to 600 nm before UV irradiation. After UV irradiation (365 nm light), a decrease in the absorption intensity of the π→π* transition band was noted and a blue-shift from 323 nm to 283 nm was exhibited. In contrast, the absorption intensity of the n→π* transition band at 434 nm increased without any shift (dashed line). Following irradiation with blue light (450 nm), the absorption spectrum returns to its original spectral pattern (dashed dotted line). The spectral changes observed in C14Azo-MA indicate its excellent photoisomerization properties, reflecting the characteristics similar to the photochemical isomerization reactions of C14Azo [7,8], involving trans→cis and cis→trans isomerization transitions.

Figure 2.

UV–Vis absorption spectra of (a) C14Azo-MA-1 (b) C14Azo-MA-2 and (c) C14Azo-MA-3 in DCM at room temperature before and after UV irradiation (365 nm, 20 mW cm−2) and blue irradiation (450 nm, 60 mW cm−2).

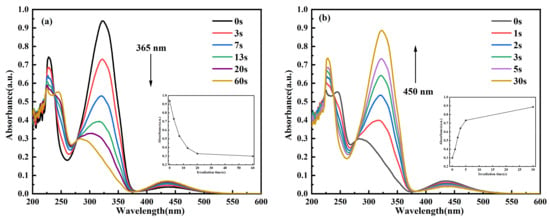

Figure 3.

Time-dependent UV–Vis absorption spectra of C14Azo-MA in DCM at room temperature. (a) C14Azo-MA-1 (c) C14Azo-MA-2 and (e) C14Azo-MA-3 irradiated by 365 nm UV light with the evolution of Abs vs. time at 323 nm shown in the inset. (b) C14Azo-MA-1 (d) C14Azo-MA-2 (f) C14Azo-MA-3 irradiated by 450 nm blue light with the evolution of Abs vs. time at 323 nm shown in the inset.

To further elucidate the time required to achieve the photostationary state (PSS) of cis↔trans C14Azo-MA, as well as the degree of isomerization, the photochemical isomerization behavior of C14Azo-MA was investigated by time-resolved UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy. As shown in Figure 3, this is the variation of absorbance of C14Azo-MA with irradiation time under UV and blue light. As the UV irradiation time increases, it can be observed that the intensity of the π-π* transition peak continuously decreases, while the intensity of the n-π* transition peak slightly increases until the PSS is reached (trans-rich→cis-rich), which takes 60 s. In other words, C14Azo-MA samples with varying C14Azo contents (35, 45, and 55 wt%) are able to reach the photostationary state after UV irradiation for 60 s. Subsequently, with the increase of blue light irradiation time, it can be found that the intensity of the π-π* transition peak continues to increase, while the intensity of the n-π* transition peak decreases slightly until it reaches PSS (cis-rich→trans-rich), and the time required to reach PSS is 30 s. These results indicate that C14Azo-MA has excellent photoisomerization performance. From a device perspective, such rapid conversion to PSS (60 s under UV and 30 s under blue light) implies potential for high-power-density applications, thereby achieving fast on-demand charging and fast heat release. However, practical designs must address the limitation of optical penetration depth in bulk materials, which favors the use of configurations such as thin films or porous structures to ensure uniform activation.

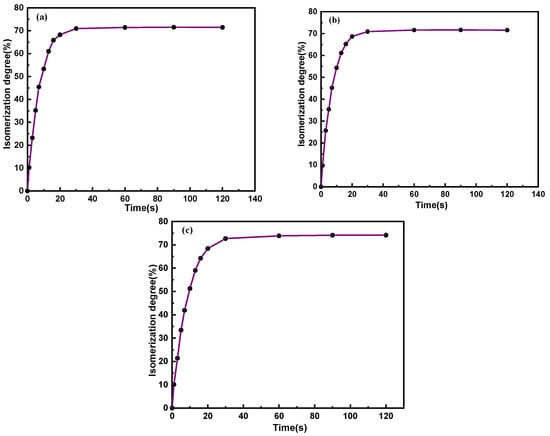

Additionally, the isomerization degree of C14Azo-MA, which is vital for energy storage, can be acquired by the formula presented in the literature [39] and plotted as shown in Figure 4. From the figure, it is evident that the amount of cis-isomer increases with increasing irradiation time under the same irradiation intensities, eventually reaching an isomerization degree of 71%, 71%, and 74% at the photostationary state, which are comparable with that of the corresponding C14Azo [7,8] and the current reports [40,41], showing that the C14Azo moiety maintains its favorable photoisomerization performance within the composite of C14Azo-MA.

Figure 4.

Isomerization degree of (a) C14Azo-MA-1, (b) C14Azo-MA-2 and (c) C14Azo-MA-3.

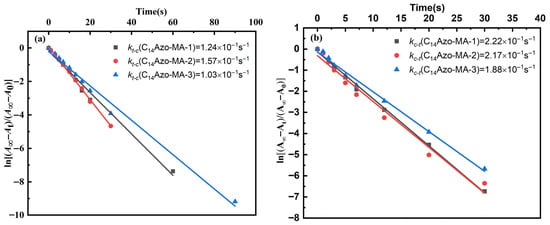

Based on the aforementioned findings that C14Azo-MA possesses a high degree of isomerization and good photoreversibility, the kinetics of the photoinduced trans-to-cis and cis-to-trans isomerization processes for C14Azo-MA in DCM solution were quantitatively studied under 365 nm and 450 nm light irradiation. The first-order rate constants for isomerization were calculated using Equation (1) [42].

where A0, At, and A∞ refer to the absorbance values of the π-π* transition at 323 nm at initial moment (time zero), a given time t, and infinite time, respectively. The variable k signifies the first-order rate constant for the photoinduced isomerization process.

ln[(A∞ − At)/(A∞ − A0)] = −kt

The first-order kinetic plots detailing photoinduced trans-to-cis and cis-to-trans isomerization of C14Azo-MA in DCM solution are shown in Figure 5. It can be observed that C14Azo-MA with varying C14Azo contents displays similar linear behavior, conforming to first-order kinetics. And the first-order rate constant for C14Azo-MA with varying C14Azo contents are all on the same order of magnitude, exhibiting the outstanding photoisomerization performance.

Figure 5.

First-order plots for (a) trans-cis and (b) cis-trans isomerization processes of C14Azo-MA.

2.3. Thermal Stability and Cyclic Stability

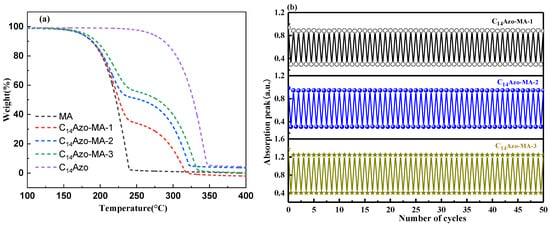

Thermal stability is one of the important performance indicators for evaluating the effectiveness and durability of materials in practical energy storage applications. Figure 6a presents the TGA curves for C14Azo, pure MA, and C14Azo-MA with different C14Azo contents. The curves reveal that all C14Azo-MA samples exhibit a two-step weight loss process, while pure C14Azo and MA exhibit only a single-step degradation. For C14Azo-MA, the former step is attributed to the bond cleavage of carbon chains in the MA component [43,44], while the latter is due to the breakage of the bonds between the nitrogen atoms of the -N=N- group and the carbon atoms of the phenyl rings in C14Azo [7,8]. Furthermore, the thermal stability of C14Azo-MA is slightly enhanced with increasing C14Azo content in the temperature range of 250 to 400 °C. This is because the degradation temperature of C14Azo is higher than that of MA, and the relative content of MA decreases as the C14Azo content increases. Overall, the C14Azo-MA showed good thermal stability up to 200 °C.

Figure 6.

(a) TGA curves and (b) cyclic stability of C14Azo-MA.

In addition, the cycling stability of C14Azo-MA was investigated through repeated 365 nm light-irradiated and 450 nm light-irradiated cycles based on the trans-cis-trans isomerization process. The trans-C14Azo-MA was converted to cis-C14Azo-MA upon UV light irradiation, and subsequently reverts back to the trans-form upon exposure to blue light. Figure 6b displays the absorbance changes (323 nm) during the trans-form→cis-form→trans-form transitions, as recorded by UV–Vis spectroscopy. The results demonstrate that C14Azo-MA possesses excellent cycling stability over 50 cycles, with no significant fatigue or degradation.

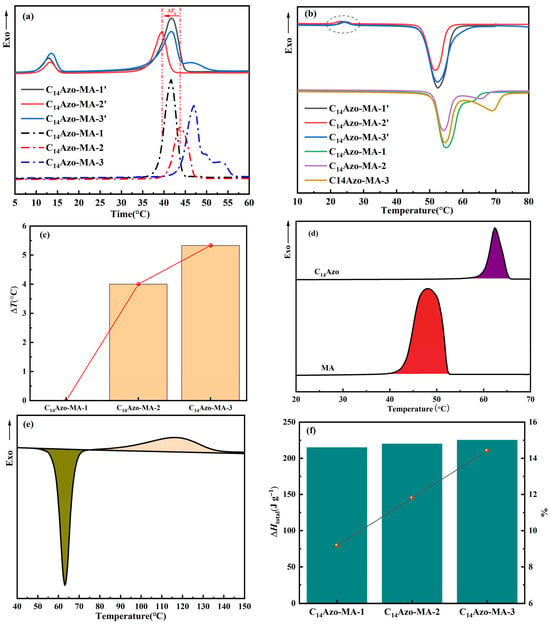

2.4. Optically-Controlled Phase Change Performance

The crystallization temperature (Tc) is widely recognized as a key parameter in practical energy storage application. The Tc of the trans- and cis-C14Azo-MA were measured by DSC, as shown in Figure 7a. Almost all of trans-C14Azo-MA samples exhibit a single peak, which is attributed to the formation of a eutectic between the trans-C14Azo and MA [8,31]. Notably, when the content of trans-C14Azo is 55 wt%, the crystallization range of C14Azo-MA is broader than that of other compositions. Besides, it can be observed that as the C14Azo content increases, the crystallization peak of C14Azo-MA shifts to higher temperatures. However, two crystallization peaks are observed for almost all cis-C14Azo-MA, corresponding to the individual crystallization of cis-C14Azo and MA (Tc ≈ 48 °C), which is clearly different from the case of trans-C14Azo-MA. This result, which is in agreement with the aforementioned XRD data, can be attributed to the enhanced interaction between cis-C14Azo and MA, specifically the formation of hydrogen bonds-a phenomenon absent in the trans-C14Azo-MA system (circled in Figure 7b), leading to a concomitant weakening of the inherent interactions of MA. Consequently, such an effect results in the Tc of MA to differ between the two systems at the same C14Azo content.

Figure 7.

Energy storage performance of C14Azo-MA. (a) DSC solidification plots of irradiated and unirradiated C14Azo-MA by UV. (b) DSC melting plots of irradiated and unirradiated C14Azo-MA by UV. (c) ΔTc of C14Azo-MA. (d) DSC exothermic heat of C14Azo and MA in the cooling stage. The purple part and red one show the crystallization of C14Azo and MA respectively. (e) DSC exothermic heat of C14Azo during cis→trans isomerization. The olive green part shows the melting of cis-C14Azo, while the light peach part shows the isomerization change of cis-C14Azo→trans-C14Azo. (f) Summary of ∆Htotal for C14Azo-MA in the bar chart and their enhancements over MA in the point and line plot.

In addition, ΔTc between trans-C14Azo-MA and cis-C14Azo-MA under different C14Azo content was comprehensively analyzed to further elucidate the optically-controlled phase change performance of C14Azo-MA. As shown in Figure 7c and Table 1, the ΔTc of C14Azo-MA increases as the C14Azo content increases. This phenomenon can be attributed to the accumulation of larger cis-C14Azo in the restricted MA. With the increase of C14Azo content, the steric hindrance imposed by bent cis-C14Azo becomes more significant, which significantly destroys the ordered arrangement of MA molecules and inhibits the nucleation process, resulting in an increase in ΔTc value. A maximum ΔTc of 5.33 °C is observed between C14Azo-MA-3 and C14Azo-MA-3′. The study indicates that this temperature difference can be effectively adjusted through the optimization of C14Azo content. More importantly, this adjustable ΔTc has important practical significance in practical thermal management. A large supercooling effect (ΔTc ≈ 5.33 °C) allows the latent heat to be locked in a metastable liquid state and released when needed, thereby avoiding spontaneous heat loss. In addition, the phase transition characteristics of these composites are highly compatible with the needs of low-grade energy harvesting and solar thermal storage. In these applications, controlled heat release is essential to maximize energy efficiency.

Table 1.

The Tc and ΔTc of C14Azo-MA with different C14Azo content.

2.5. Energy Storage Performance and Durability Assessment

Energy density stands as a crucial metric for energy storage capabilities of OPCMs. The overall energy density of C14Azo-MA comprises both the latent heat of phase change and the enthalpy of isomerization, and can be determined by Equation (2) [8,34].

where ∆Htotal represents the total heat released during the cis→trans isomerization and phase transition of C14Azo-MA. ∆HMA and ∆Htrans-C14Azo corresponds to is the crystallization enthalpy of MA and trans-C14Azo, respectively. ∆Hiso(C14Azo) denotes the isomerization enthalpy of C14Azo, and χ is the content (mass fraction) of MA in C14Azo-MA.

∆Htotal = χ∆HMA + (1 − χ)∆Htrans-C14Azo + (1 − χ)∆Hiso(C14Azo)

DSC analysis was conducted to determine ∆HMA, ∆Htrans-C14Azo, and ∆Hiso(C14Azo) for the calculation of ∆Htotal. From Figure 7d,e, ∆HMA, ∆Htrans-C14Azo, and ∆Hiso(C14Azo) were found to be 196.71 J g−1, 142.70 J g−1, and 105.59 J g−1, respectively. Using Equation (2), these values were calculated and plotted as the bar chart in Figure 7f, which shows that the ∆Htotal of C14Azo-MA rises as C14Azo content increases. Ultimately, the ∆Htotal obtained for C14Azo-MA-1, C14Azo-MA-2, and C14Azo-MA-3 were 214.76 J g−1, 219.92 J g−1, and 225.08 J g−1, respectively, corresponding to enhancements of 9.18%, 11.80%, and 14.42% over MA (as shown in the point and line plot in Figure 7f). This enhancement in ∆Htotal is mainly due to the strengthened intermolecular interactions as well as the extra photochemical energy stored by the C14Azo compound. The result indicates that the C14Azo-MA shows higher density energy than other AZO-fatty acid systems previously reported [31,34,35] and is comparable to AZO-OPCMs for solar energy storage application [7,8]. To explicitly highlight these advantages, a comprehensive comparison of key thermal metrics, including total enthalpy (∆Htotal), crystallization temperature (Tc), and photoinduced crystallization temperature difference (ΔTc), is presented in Table 2. As summarized in the table, the C14Azo-MA achieves a superior energy density of 225.08 J g−1 through the chain-length matching strategy, surpassing the typical values observed in mismatched counterparts. This incremental yet significant gain confirms the effectiveness of optimizing molecular interactions for high-performance thermal storage.

Table 2.

A comparison of ∆Htotal, Tc and ΔTc of azobenzene-OPCM systems from the latest reports.

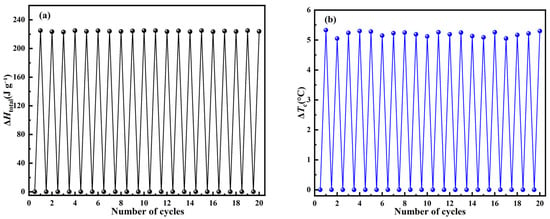

In addition to the aforementioned UV–Vis level cycle stability, DSC level cycle stability is also a performance index to determine the durability of C14Azo-MA. The durability of C14Azo-MA was investigated through repeated DSC measurements involving 365 nm light irradiation and heating/cooling. C14Azo-MA-3 was selected as samples for durability testing due to its superior performance in optically-controlled phase transitions. The C14Azo-MA-3 in the trans-rich state was subjected to 365 nm UV light, transforming it into the cis-rich state. The subsequent reversion from cis-rich to trans-rich state was achieved through heating using DSC. Figure 8a,b shows the changes in ΔHtotal and ΔTc from trans-rich to cis-rich to trans-rich state, respectively. The ΔHtotal of sample C14Azo-MA-3 is 223.56 J g−1–225.08 J g−1 and the ΔTc of sample C14Azo-MA-3 is 5.05 °C–5.33 °C. The result shows an excellent durability of C14Azo-MA over 20 cycles without noticeable attenuation.

Figure 8.

Durability assessment of C14Azo-MA (a) ∆Htotal and (b) ΔTc.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of C14Azo-MA

All the main materials used without further purification were obtained from commercial sources, unless otherwise mentioned. The C14Azo molecule was synthesized according to our previous work [8] (1H NMR, 400 MHz, CDCl3-d): δ (ppm) = 7.96 (m, 2H), 7.91 (m, 2H), 7.50 (m, 3H), 7.25 (m, 2H), 2.59 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.78 (m, 2H), 1.32 (m, 16H), 0.89 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H).

C14Azo-MA was prepared by the melting method. Specifically, C14Azo was mixed with myristic acid (MA) at mass fractions of 35 wt%, 45 wt%, and 55 wt%, respectively. The mixture was heated until completely melted, followed by mechanical stirring for 30 min. After natural cooling, the C14Azo-MA composite materials (trans-C14Azo-MA) were obtained and labeled as C14Azo-MA-1, C14Azo-MA-2, and C14Azo-MA-3, respectively. The solid-state C14Azo-MA composites were then transferred onto glass substrates for further ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. After irradiation, the materials (cis-C14Azo-MA) were labeled as C14Azo-MA-1′, C14Azo-MA-2′, and C14Azo-MA-3′, respectively.

3.2. Characterizations

The 1H NMR (400-MHz, AVANCE IIITM HD, Bruker, Mannheim, Germany) of C14Azo were tested using a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, with deuterated chloroform (CDCl3-d) as the solvent and testing ranges of 0–20 ppm. A FT-IR (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to characterize the vibration modes of the C14Azo and C14Azo-MA group, with the sample prepared using potassium bromide pellets and a testing range of 4000–400 cm−1. XRD (Ultima IV, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) patterns were obtained by Cu Kα radiation (k = 0.15 nm) at a scanning rate of 5.0 min−1.

The photoisomerization properties of C14Azo-MA in DCM solution using 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvettes were characterized using UV–Vis (UV-1900i, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) with UV (365 nm) light intensity of 20 mW cm−2 and blue (450 nm) light intensity of 60 mW cm−2. Subsequently, the samples were irradiated with a light source of a specified wavelength until a photostationary state (PSS) was reached, that is, no change in absorbance was observed.

The thermal stability of C14Azo-MA was tested using TGA (SDT Q600, TA Instruments, Newcastle, DE, USA) in a nitrogen atmosphere, within a temperature range of 25–400 °C, at a heating rate of 10 °C min−1 and a gas flow rate of 50 mL min−1. The Tc and energy density of C14Azo-MA were measured using DSC (DSC3, Mettler Toledo, Zurich, Switzerland) under a nitrogen atmosphere, with the heating/cooling rate set at 20 °C min−1. The process is shown as follows. Solid C14Azo-MA with different C14Azo content were heated at 59 °C to absorb external thermal energy, and then irradiated by a UV lamp (365 nm, 80 mW cm−2) to store optical energy. After 1 h of irradiating, the samples were transferred to DSC pans in the dark for DSC test.

4. Conclusions

A composite material, C14Azo-MA, was successfully prepared by doping MA with C14Azo featuring an identical carbon chain length, designed for solar energy storage and controlled release. The composite was found to preserve the robust photoisomerization properties of the C14Azo dopant. The incorporation of these photo-responsive C14Azo molecules induces tunable supercooling and modifies the crystallization behavior of the system. Additionally, the supercooling degree and energy density can be tuned by adjusting the mass fractions of C14Azo in the composite, allowing for stable thermal energy storage below the intrinsic freezing point of the MA. Specifically, the ΔTc and ∆Htotal of C14Azo-MA increases as the C14Azo content increases. Eventually, the maximum supercooling degree reached is 5.33 °C. By synergistically storing both latent heat of crystallization and isomerization energy, the C14Azo-MA composite achieves a remarkable energy density of 225.08 J g−1, which surpasses that of pure MA by 14.42%. The system also maintained excellent stability. This study opens a new avenue for designing high-capacity photothermal storage systems for solar energy storage applications.

Author Contributions

Y.J.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. J.C., Y.G. and R.L.: investigation, formal analysis. H.W.: writing—review and editing, formal analysis. J.H.: resources, methodology, conceptualization. W.L.: writing—review and editing, resources, formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2025A1515011649); the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2022A1515110775); the Characteristic Innovation Project of Universities in Guangdong (No. 2024KTSCX031; No. 2023KTSCX154); the Zhaoqing University High-level Project Training Program Funding Project (No. GCCZK202414); the Zhaoqing University Research Funding Project (No. 2019010127, No. 190128).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPCMs | Organic phase change materials |

| AZO | Azobenzene |

| ΔHiso | Isomerization enthalpy |

| ΔTc | Photoinduced crystallization temperature difference |

| MA | Myristic acid |

| C14Azo | Azobenzene derivative |

| C14Azo-MA | Azobenzene-based organic phase change composite |

| FT-IR | Fourier transform infrared |

| 1HNMR | Proton nuclear magnetic resonance |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| UV–Vis | UV–visible |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analyzer |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimeter |

| DCM | Dichloromethane |

| A0 | The absorbance values of the π-π* transition at 323 nm at initial moment (time zero) |

| At | The absorbance values of the π-π* transition at 323 nm at a given time t |

| A∞ | The absorbance values of the π-π* transition at 323 nm at infinite time |

| k | First-order kinetic constants |

| kt-c | First-order rate constants from trans to cis |

| kc-t | First-order rate constants from cis to trans |

| Tc | Crystallization temperature |

| ∆Htotal | The total heat released during the cis→trans isomerization and phase transition of C14Azo-MA |

| ∆HMA | The crystallization enthalpy of MA |

| ∆Htrans-C14Azo | The crystallization enthalpy of trans-C14Azo |

| ∆Hiso(C14Azo) | The isomerization enthalpy of C14Azo |

| χ | The content (mass fraction) of MA in C14Azo-MA |

References

- Wu, X.; Mo, C.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Lin, R.; Zeng, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, X. Experiment investigation on optimization of cylinder battery thermal management with microchannel flat tubes coupled with composite silica gel. J. Energy Storage 2022, 56, 105871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jia, S.; Niu, Y.; Lv, X.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, B.; Li, Q. Bean-pod-inspired 3D-printed phase change microlattices for solar-thermal energy harvesting and storage. Small 2021, 17, 2101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhu, L.; Song, J. Green building design based on solar energy utilization: Take a kindergarten competition design as an example. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 1297–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kuang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Transforming a solar-rich county to an electricity producer: Solutions to the mismatch between demand and generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernaat, D.E.H.J.; Boer, H.S.; Daioglou, V.; Yalew, S.G.; Muller, C.; Vuuren, D.P. Climate change impacts on renewable energy supply. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, S.C.; Barthelmie, R.J.; Bukovsky, M.S.; Leung, L.R.; Sakaguchi, K. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, J.; Luo, W.; Quan, X.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Feng, W. High-energy and light-actuated phase change composite for solar energy storage and heat release. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 24, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.; Luo, W.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Huang, J. Photoguided AZO-phase change composite for high-energy solar storage and heat release at near ambient temperature. J. Energy Storage 2024, 10, 113974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchikova, Y.; Nazarovets, S.; Konuhova, M.; Popov, A.I. BinaryOxide Ceramics (TiO2, ZnO, Al2O3, SiO2, CeO2, Fe2O3, and WO3) for Solar Cell Applications: A Comparative and Bibliometric Analysis. Ceramics 2025, 8, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, R.J.; Moth-Poulsen, K. Multichromophoric photoswitches for solar energy storage: From azobenzene to norbornadiene, and MOST things in between. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 3180–3208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Moïse, H.; Cacciarini, M.; Nielsen, M.B.; Morikawa, M.; Kimizuka, N.; Moth-Poulsen, K. Liquid-based multijunction molecular solar thermal energy collection device. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.F.; Zsembinszki, G.; Martín, M. Evaluation of volume change in phase change materials during their phase transition. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Palacios, A.; Zou, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Review on phase change materials for cold thermal energy storage applications. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2020, 134, 110340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.A.; Habib, K.; Younas, M.; Rahman, S.; Das, L.; Rubbi, F.; Mulk, W.U.; Rezakazemi, M. Advancements in thermal energy storage: A review of material innovations and strategic approaches for phase change materials. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 19336–19392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Li, T.; Wu, M.; Xu, J.; Hu, Y.; Chao, J.; Yan, T.; Wang, R. Highly thermally conductive and flexible phase change composites enabled by polymer/graphite nanoplatelet-based dual networks for efficient thermal management. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 20011–20020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribezzo, A.; Morciano, M.; Zsembinszki, G.; Amigó, S.R.; Kala, S.M.; Borri, E.; Bergamasco, L.; Fasano, M.; Chiavazzo, E.; Prieto, C.; et al. Enhancement of heat transfer through the incorporation of copper metal wool in latent heat thermal energy storage systems. Renew. Energy 2024, 231, 120888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, T.; Wang, P.; Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Lin, J. Dual-encapsulated highly conductive and liquid-free phase change composites enabled by polyurethane/graphite nanoplatelets hybrid networks for efficient energy storage and thermal management. Small 2022, 18, 2105647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathunga, D.S.; Karunathilake, H.P.; Narayana, M.; Witharana, S. Phase change material (PCM) candidates for latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES) in concentrated solar power (CSP) based thermal applications—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 189, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Samykano, M.; Kalidasan, B.; Said, Z. A review of organic phase change materials and their adaptation for thermal energy storage. Int. Mater. Rev. 2024, 69, 380–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodrati, A.; Zahedi, R.; Ahmadi, A. Analysis of cold thermal energy storage using phase change materials in freezers. J. Energy Storage 2022, 51, 104433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, Q.; Luo, L.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jia, G. Research progress on the phase change materials for cold thermal energy storage. Energies 2021, 14, 8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Villalobos, U.; Akhmetov, B.; Gil, A.; Khor, J.O.; Palacios, A.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Cabeza, L.F.; Tan, W.L.; et al. A comprehensive review on sub-zero temperature cold thermal energy storage materials, technologies, and applications: State of the art and recent developments. Appl. Energy 2021, 28, 116555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Li, X.; Liang, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, D.; Deng, Q.; Wu, Z. Investigation on the thermal contact resistance mechanism of a composite phase change material for battery thermal management. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 1810–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhao, G.; Li, X.; Rao, Z. Investigation on the battery thermal management and thermal safety of battery-powered ship with flame-retardant composite phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2024, 81, 110228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Tong, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Deng, J. Research on morphological control and temperature regulation of phase change microcapsules with binary cores for electronics thermal management. Thermochim. Acta 2021, 70, 179079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Calautit, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, H. A review of the applications of phase change materials in cooling, heating and power generation in different temperature ranges. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 242–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omara, A.A.M. Phase change materials for waste heat recovery in internal combustion engines: A review. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Ji, C.; Low, Z.H.; Tong, W.; Wu, C.; Duan, F. Geometry effect of phase change material container on waste heat recovery enhancement. Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, B.M.; Shukla, S.K.; Rathore, P.K.S. A comprehensive review on solar to thermal energy conversion and storage using phase change materials. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, J.; Xia, J.; Zhai, F.; Dong, L. Visible-light-controlled thermal energy storage and release: A tetra-ortho-fluorinated azobenzene-doped composite phase change material. Molecules 2025, 30, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Sheng, L.; Chen, Z. Study on the applicability of photoswitch molecules to optically-controlled thermal energy in different organic phase change materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 456, 141051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, M.; Tamaoki, N. Planar chiral azobenzenophanes as chiroptic switches for photon mode reversible reflection color control in induced chiral nematic liquid crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11409–11416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Mafy, N.N.; Maisonneuve, S.; Lin, C.; Tamaoki, N.; Xie, J. Glycomacrocycle-based azobenzene derivatives as chiral dopants for photoresponsive cholesteric liquid crystals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 52146–52155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.G.D.; Li, H.S.; Grossman, J.C. Optically-controlled long-term storage and release of thermal energy in phase-change materials. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.G.D.; Deru, J.H.; Cho, E.N.; Grossman, J.C. Optically-regulated thermal energy storage in diverse organic phase-change materials. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 10722–10725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Tang, J.; Dong, L.; Wang, H.; Xu, T.; Gao, W.; Zhai, F.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Optically triggered synchronous heat release of phase-change enthalpy and photothermal energy in phase-change materials at low temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 11, 2008496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, G.; Huang, X.; Liu, L.; Fang, G. Synthesis and characterization of microencapsulated myristic acid–palmitic acid eutectic mixture as phase change material for thermal energy storage. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.L.; Zhu, F.R.; Yu, S.B.; Xiao, Z.L.; Yan, W.P.; Zheng, S.H. Myristic acid/polyaniline composites as form stable phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 114, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yuan, D.; Yuan, T.; Dong, J.; Feng, N.; Han, G. A visible light responsive azobenzene-functionalized polymer: Synthesis, self-assembly, and photoresponsive properties. J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Chem. 2015, 53, 2768–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ge, J.; Qin, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, B.; Feng, Y.; Feng, W. Controllable heat release of phase-change azobenzenes by optimizing molecular structures for low-temperature energy utilization. Sci. China Mater. 2023, 66, 3609–3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, J.; Qi, J.; Tang, F.; Zhai, F.; Dong, L. A tetra-ortho-chlorinated azobenzene molecule for visible-light photon energy conversion and storage. Molecules 2025, 30, 2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, S.L.; Gan, L.H.; Hu, X.; Tam, K.C.; Gan, Y.Y. Photochemical and thermal isomerizations of azobenzene-containing amphiphilic diblock copolymers in aqueous micellar aggregates and in film. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 3943–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, M.; Gürgenç, E.; Coşanay, H.; Öztop, H.F. Novel nano-Y2O3/myristic acid nanocomposite PCM for cooling performances of electronic device with various fin designs. J. Energy Storage 2024, 100, 113646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y. Effective thermal management enabled by encapsulation of phase change myristic acid in silica shells for coatings: Experimental and molecular dynamics studies. Energy 2024, 313, 133865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.