Preparation of a Supramolecular Assembly of Vitamin D in a β-Cyclodextrin Shell with Silver Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Synthetic Procedures

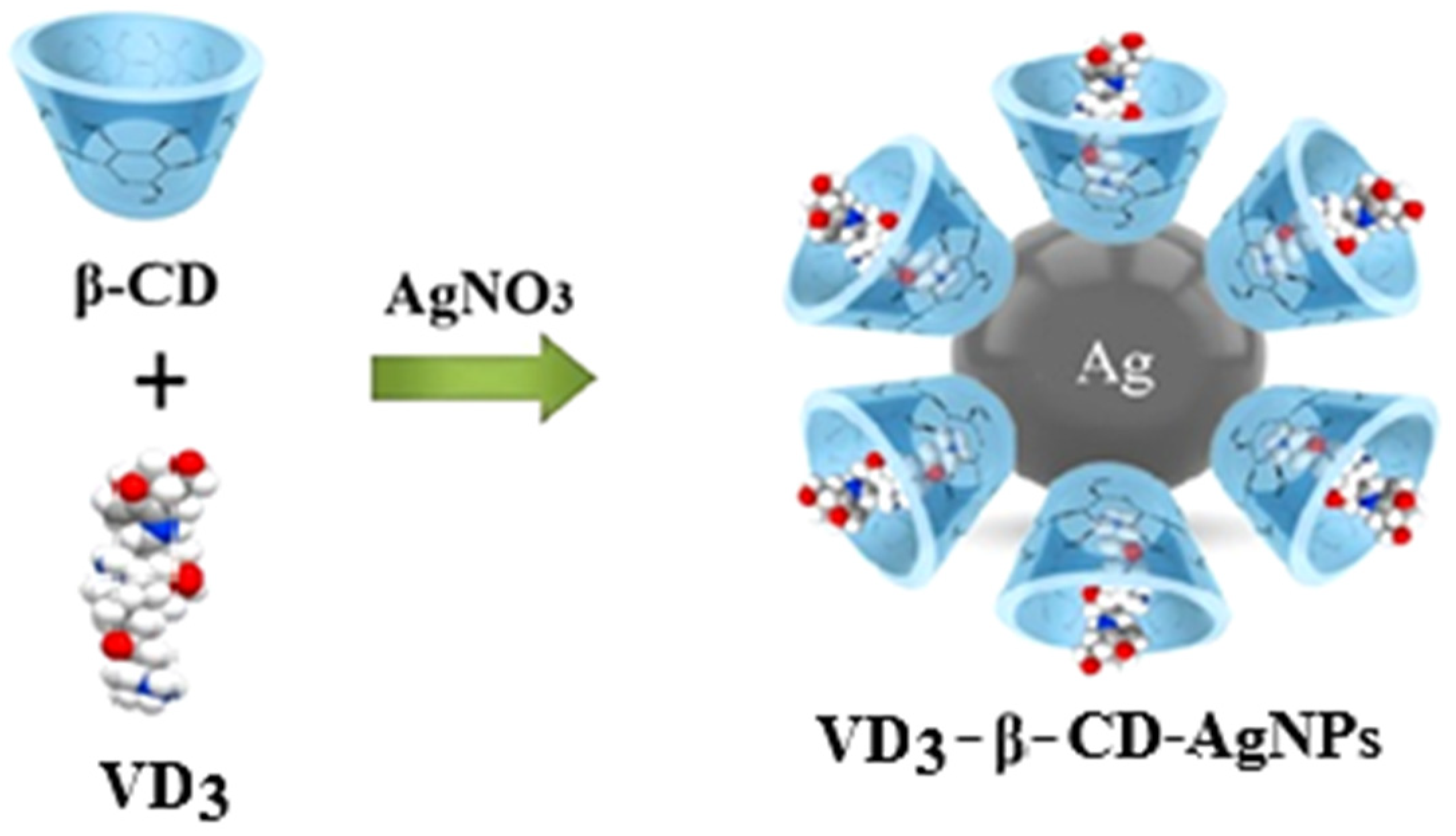

2.2. Preparation of the VD3–β-CD–AgNP Inclusion Complexes

2.3. Bacteria and Cultivation Conditions

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

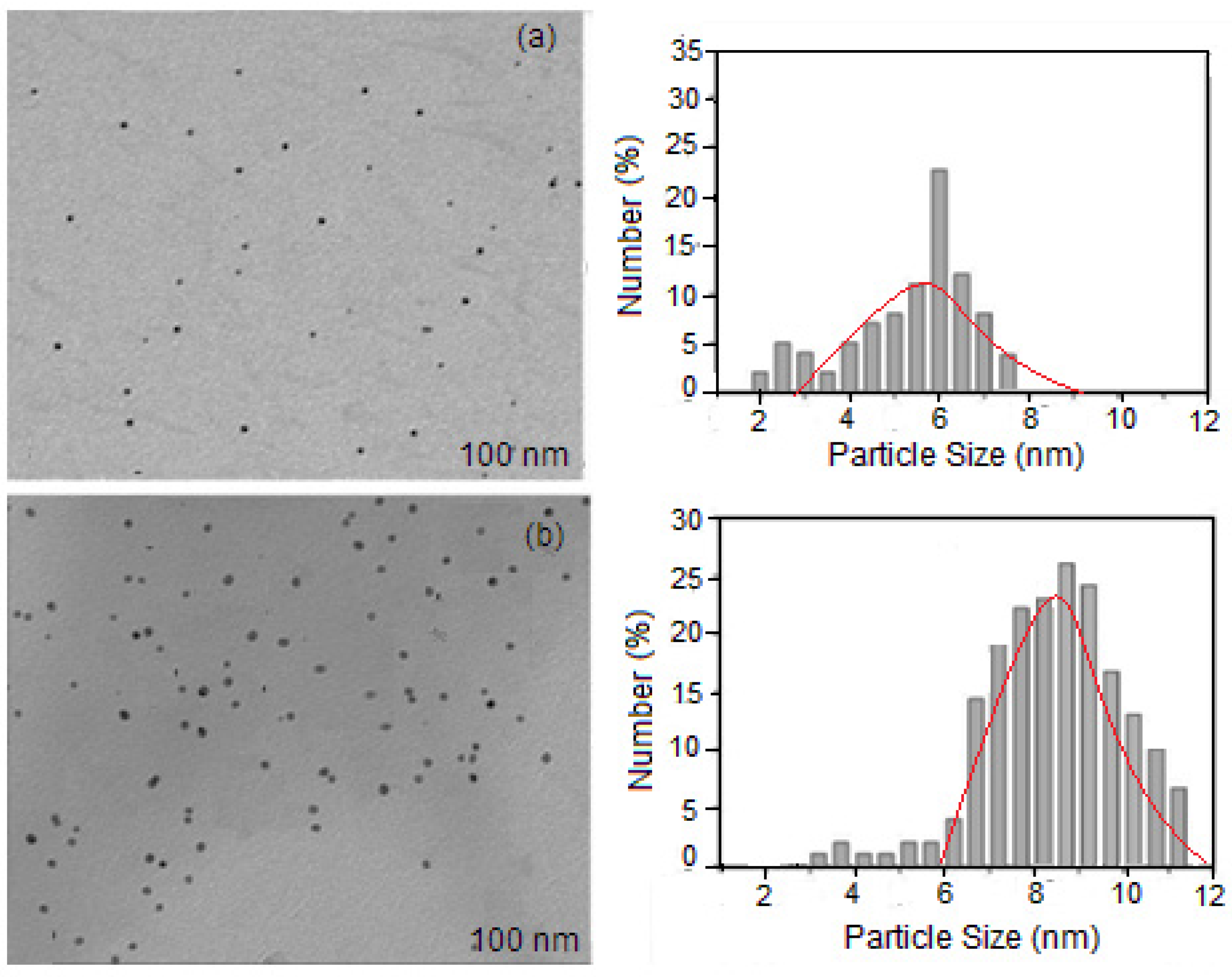

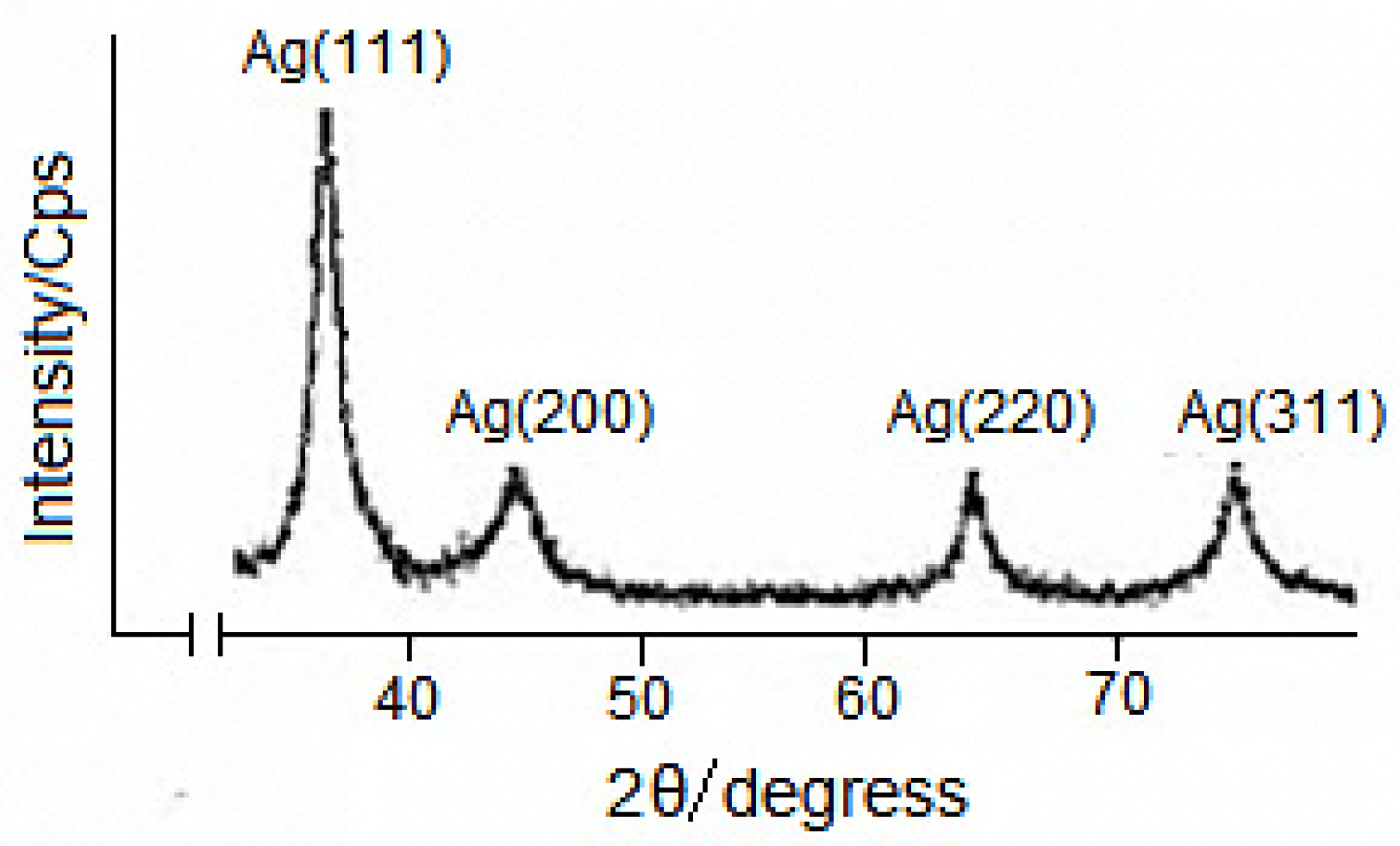

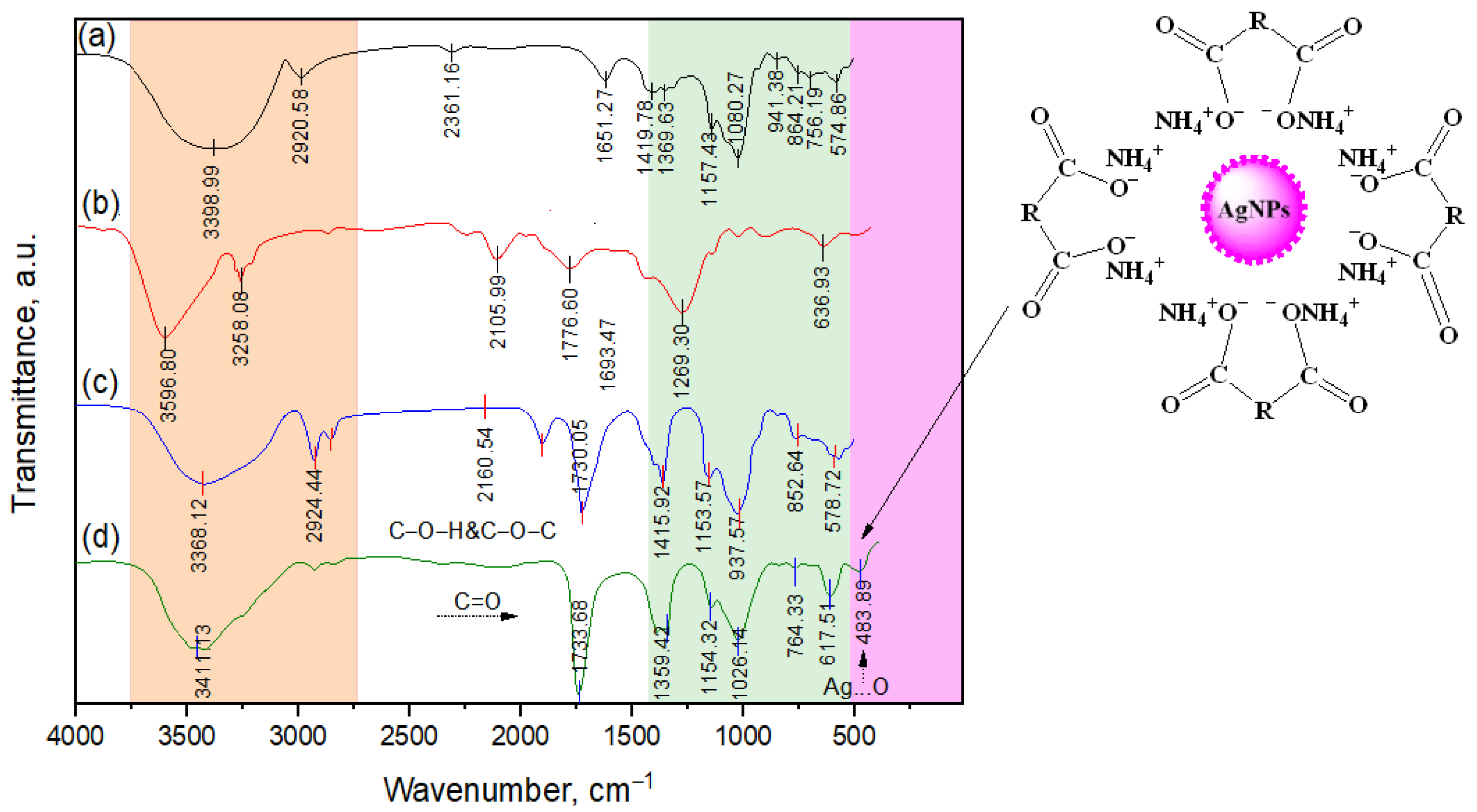

3.1. Characteristics of the Structure of VD3-β-CD-AgNP Nanocomposites

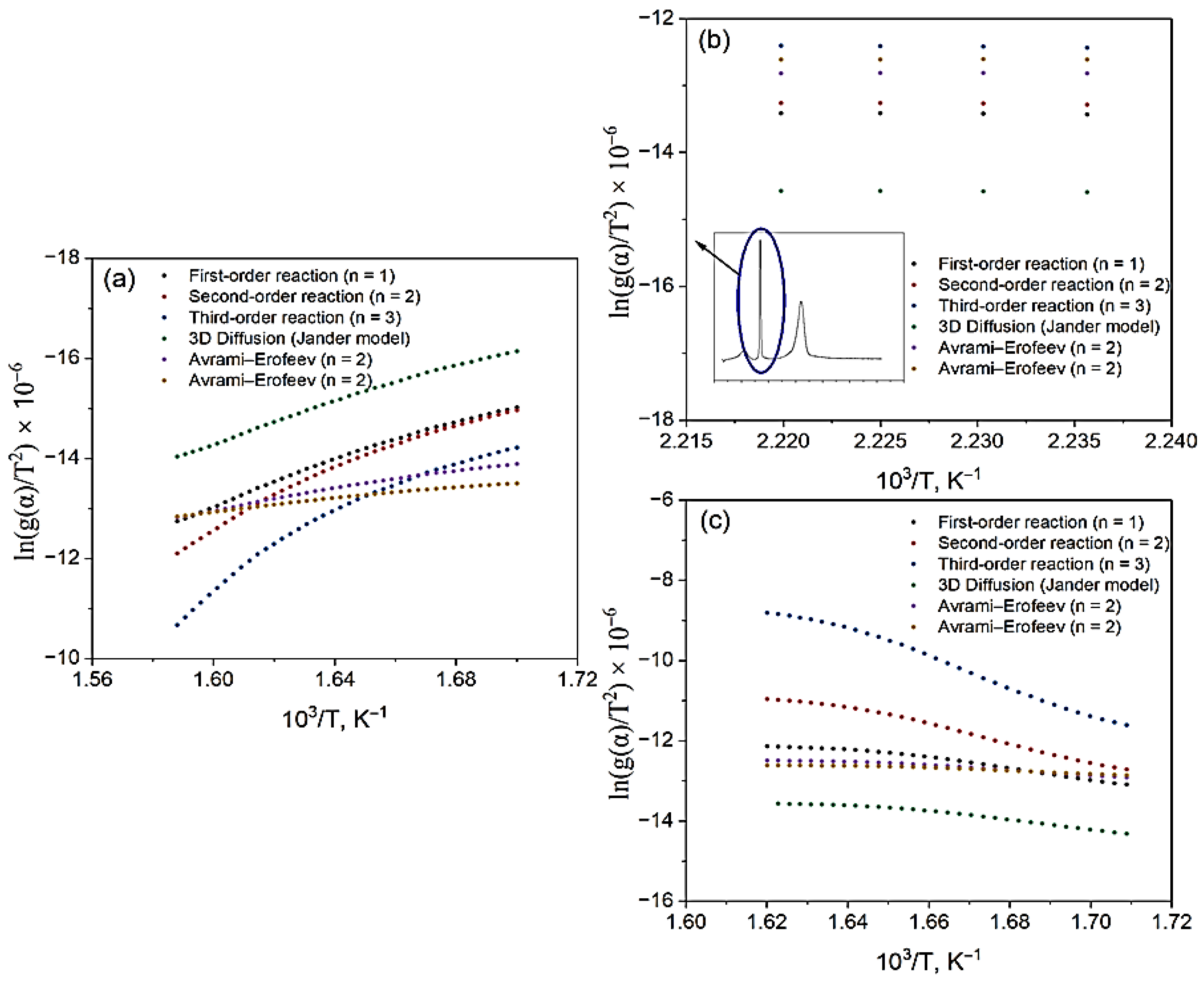

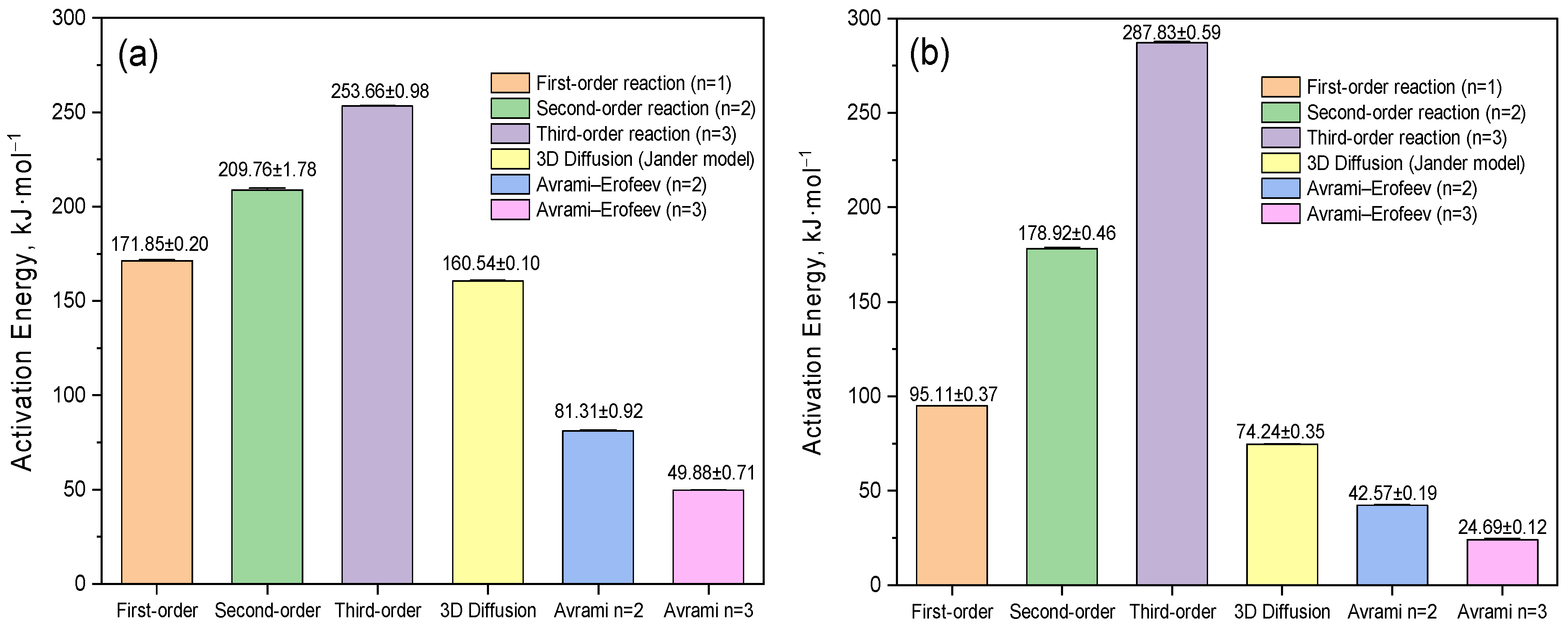

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis of β-CD–AgNP, VD3–β-CD and VD3–β-CD–AgNP

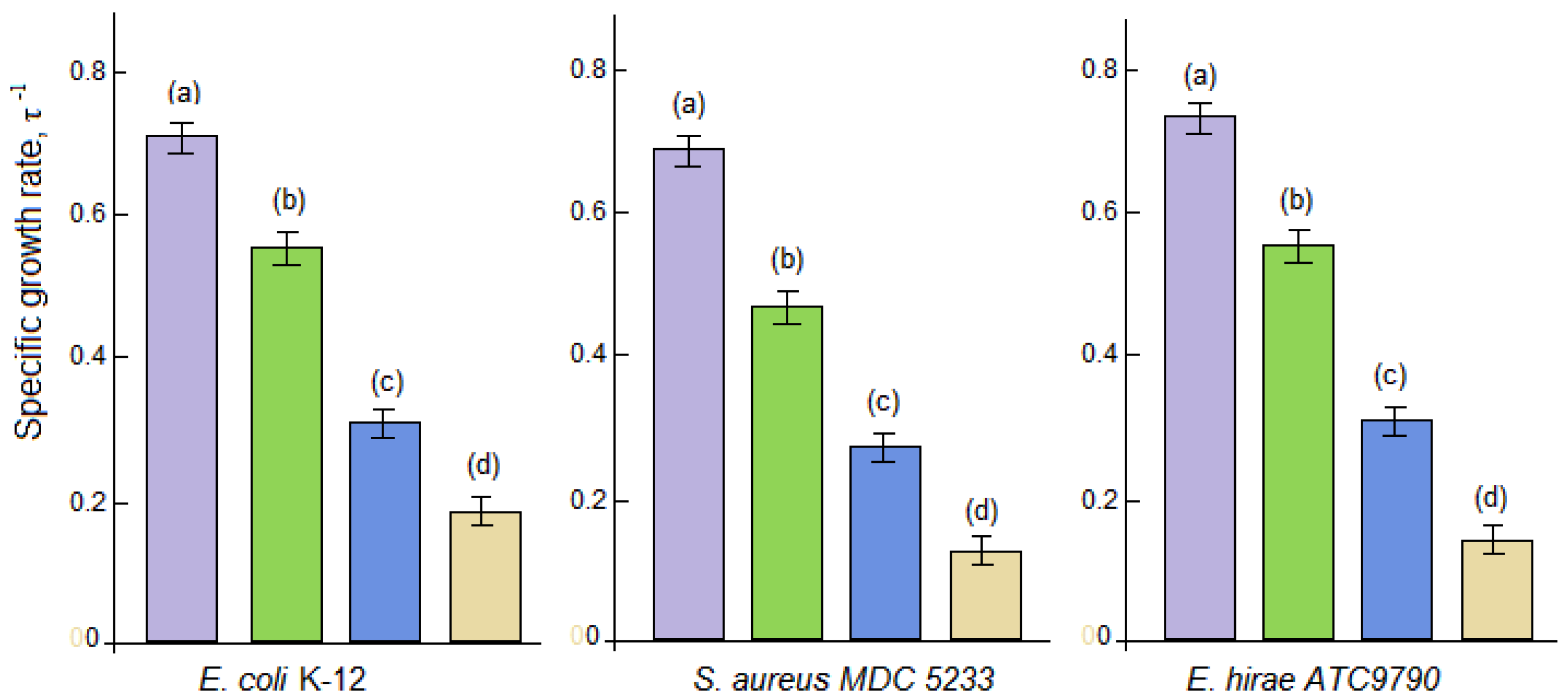

3.3. Antibacterial Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holick, M.F.; Chen, T.C. Vitamin D deficiency: A worldwide problem with health consequence. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1080S–1086S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H. Study of VD3-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. J. Geosci. Environ. Prot. 2016, 4, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauryaa, V.K.; Bashirb, K.; Aggarwala, M. Vitamin D microencapsulation and fortification: Trends and technologies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020, 196, 105489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, Q.E.; Umbach, D.M.; Baird, D.D. Use of Estrogen-Containing Contraception Is Associated With Increased Concentrations of 25-Hydroxy Vitamin. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 3370–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari Heike, A.; Willet Walter, C.; Wong John, B.; Giovannucci, E.; Dietrich, T.; Dawson-Hughes, B. Fracture Prevention with Vitamin D Supplementation. Am. Medic. Assoc. 2005, 293, 2257–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirova, R.; Nukhuly, A.; Iskineyeva, A.; Fazylov, S.; Burkeyev, M.; Mustafayeva, A.; Minayeva, Y.; Sarsenbekova, A. Obtaining and Investigation of the β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex with Vitamin D3 Oil Solution. Scientifica 2020, 2020, 6148939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legarth, C.; Grimm, D.; Wehland, M.; Bauer, J.; Kruger, M. The impact of vitamin D in the treatment of essential hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astray, G.; Gonzalez-Barreiro, C.; Mejuto, J.C.; Rial-Otero, R.; Simal-Gándara, J. A Review on the Use of Cyclodextrins in Foods. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 1631–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szejtli, J.; Bolla-Pusztai, E.; Szabo, P.; Ferenczy, T. Enhancement of Stability and Biological Effect of Cholecalciferol by β-Cyclodextrin Complexation. Pharmazie 1980, 35, 779–787. [Google Scholar]

- Merce, A.L.R.; Yano, L.S.; Khan, M.A.; Thanh, X.D.; Bouet, G. Complexing Power of Vitamin D3 Toward Various Metals. Potentiometric Studies of Vitamin D3 Complexes with AI3+, Cd2+, Gd3+, and Pb2+ Ions in Water-Ethanol Solution. J. Solut. Chem. 2003, 32, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.K.; Dey, S. Effects and applications of silver nanoparticles in different fields. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2015, 6, 5880–5883. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, V.K.; Kamle, M.; Shukla, S.; Mahato, D.K.; Chandra, P. Prospects of using nanotechnology for food preservation, safety, and security. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Hwang, H.M. Nanotechnology in food science: Functionality, applicability, and safety assessment. J. Food Drug Anal. 2016, 24, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Domencia, D.; Sabbatella, G.; Antiochia, R. Silver nanoparticles in polymeric matrices for fresh food packaging. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2016, 28, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camberos, E.P.; Hernandez, I.M.S.; Aguirre, S.I.J.; Garcia, J.J.O.; Cervantes, C.M. Food Industry Applications of Phyto-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Glob. J. Nutri. Food Sci. 2019, 2, 000537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merce, R.A.L.; Nicolini, J.; Khan, M.A.; Bouet, G. Qualitativ study of supramolecular assamblies of beta-cyclodextrin and cholecalciferl and the cobalt (II), copper (II) and zinc (II) ions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, L.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Gevorgyan, V.; Ananyan, M.; Trehounian, A. Effect of iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles: Distinguishing concentration-dependent effects with different bacterial cells grouth and membrane-associated mechanisms. Appl. Microbiol. Biothechnol. 2019, 103, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielyan, L.; Nakbyan, L.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Trchounian, A. Effects of iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles on Escherichia coli antibiotic-resistant strains. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.X.; Li, C.M.; Huang, C.Z. Curcumin modified silver nanoparticles for highly efficient inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Nanoscale 2016, 8, 3040–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, D.F.; Noseda, M.D.; Felcman, J.; Khan, M.A.; Bouet, G.; Mercê, A.L.R. Supramolecular assemblies of Al3+ complexes with vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) and phenothiazine. Encapsulation and complexation studies in β-cyclodextrin. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2013, 75, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Liu, J.; Luo, L.; Li, M.; Xu, T.; Zan, J. Synthesis of cationic b-cyclodextrin functionalized silver nanoparticles and their drug-loading applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ze, H.; Yan Sun, X.; Jing, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Shakoor, A.; Guo, J. UV-irradiation synthesis of cyclodextrin-silver nanocluster decorated TiO2-nanoparticles for photocatalytic enchanced anticancer effect on Hela cancer cells. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 99261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, M.; Hamid, A.; Bakar, F.A.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Shameli, K.; Jahanshiri, F.; Farahani, F. Green Synthesis and Antibacterial Effect of Silver Nanoparticles Using Vitex negundo L. Molecules 2011, 16, 6667–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shameli, K.; Ahmad, M.B.; Jazayeri, S.D. Investigation of antibacterial properties silver nanoparticles prepared via green method. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakowski, M.; Ejchart, A. Complex formation of fenchone with α-cyclodextren: NMR titrations. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2014, 79, 337–342. [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari, A.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, D. Complexation of sodium picosulphate with beta cyclodextri: NMR spectroscopic study in solution. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2013, 77, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, A.W.; Redfern, J.P. Kinetic parameters from thermo-gravimetric data. Nature 1964, 201, 68–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrami, M. Granulation, Phase Change, and Microstructure Kinetics of Phase Change II. J. Chem. Phys. 1941, 9, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardanyan, Z.; Gevorkyan, V.; Ananyan, M.; Vardapetyan, H.; Trchounian, A. Effect of various heavy metal nanoparticles on Enterococcus hirae and Escherichia coli growth and proton-coupled membrane transport. J. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, J.; Shao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Xu, T.; Guo, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, R.; Lin, H. Thermal behavior and kinetic analysis of co-combustion of waste biomass/low rank coal blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 124, 414–426. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.S.; Yong, G.P.; Yan, X.Y.; Hu, Y. Comparison to the thermal decomposition kinetics of several inclusion complex of b-cyclodextrin. Chem. Res. Appl. 2003, 15, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Hu, C.; Shao, L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: Present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1227–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdusel, A.C.; Gherasim, O.; Grmezescu, A.M.; Mogoanta, L.; Ficai, A.; Andronescu, E. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: An up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Jun, B.H. Silver nanoparticles: Synthesis and application for nanomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MsShan, D.; Ray, P.S.; Yu, H. Molecular toxicity mechanism of nanosilver. J. Food Drug Anal. 2014, 22, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Atom Number | β-CD (δ0) (ppm) | β-CD-VD3 (δ) (ppm) | Δδ (δ-δ0) (ppm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ (1H) | Δ (13C) | δ (1H) | Δ (13C) | δ (1H) | Δ (13C) | |

| C1 | 4.823 | 102.43 | 4.736 | 102.23 | −0.087 | −0.18 |

| C2 | 3.543 | 72.85 | 3.455 | 72.81 | −0.078 | −0.04 |

| C3 | 3.510 | 73.55 | 3.395 | 73.43 | −0.115 | −0.12 |

| C4 | 3.477 | 82.15 | 3.439 | 82.08 | −0.038 | −0.07 |

| C5 | 3.352 | 72.51 | 3.235 | 72.39 | −0.117 | −0.12 |

| C6 | 3.630 | 60.37 | 3.547 | 60.24 | −0.083 | −0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakirova, R.Y.; Fazylov, S.D.; Iskineyeva, A.S.; Sarsenbekova, A.Z.; Sviderskiy, A.K.; Seilkhanov, O.T.; Mustafayeva, A.K.; Mendibayeva, A.Z.; Ashirbekova, B.D.; Agedilova, M.T.; et al. Preparation of a Supramolecular Assembly of Vitamin D in a β-Cyclodextrin Shell with Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30, 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244823

Bakirova RY, Fazylov SD, Iskineyeva AS, Sarsenbekova AZ, Sviderskiy AK, Seilkhanov OT, Mustafayeva AK, Mendibayeva AZ, Ashirbekova BD, Agedilova MT, et al. Preparation of a Supramolecular Assembly of Vitamin D in a β-Cyclodextrin Shell with Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244823

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakirova, Ryszhan Y., Serik D. Fazylov, Ainara S. Iskineyeva, Akmaral Zh. Sarsenbekova, Aleksandr K. Sviderskiy, Olzhas T. Seilkhanov, Ayaulym K. Mustafayeva, Anel Z. Mendibayeva, Bolatkul Dh. Ashirbekova, Mereke T. Agedilova, and et al. 2025. "Preparation of a Supramolecular Assembly of Vitamin D in a β-Cyclodextrin Shell with Silver Nanoparticles" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244823

APA StyleBakirova, R. Y., Fazylov, S. D., Iskineyeva, A. S., Sarsenbekova, A. Z., Sviderskiy, A. K., Seilkhanov, O. T., Mustafayeva, A. K., Mendibayeva, A. Z., Ashirbekova, B. D., Agedilova, M. T., & Khabdolda, G. (2025). Preparation of a Supramolecular Assembly of Vitamin D in a β-Cyclodextrin Shell with Silver Nanoparticles. Molecules, 30(24), 4823. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244823