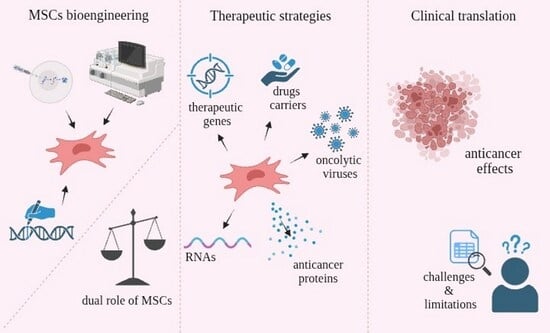

Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cancer Therapy: Advanced Therapeutic Strategies Towards Future Clinical Translation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Recruitment Mechanisms and MSC Activity in the Tumor Microenvironment

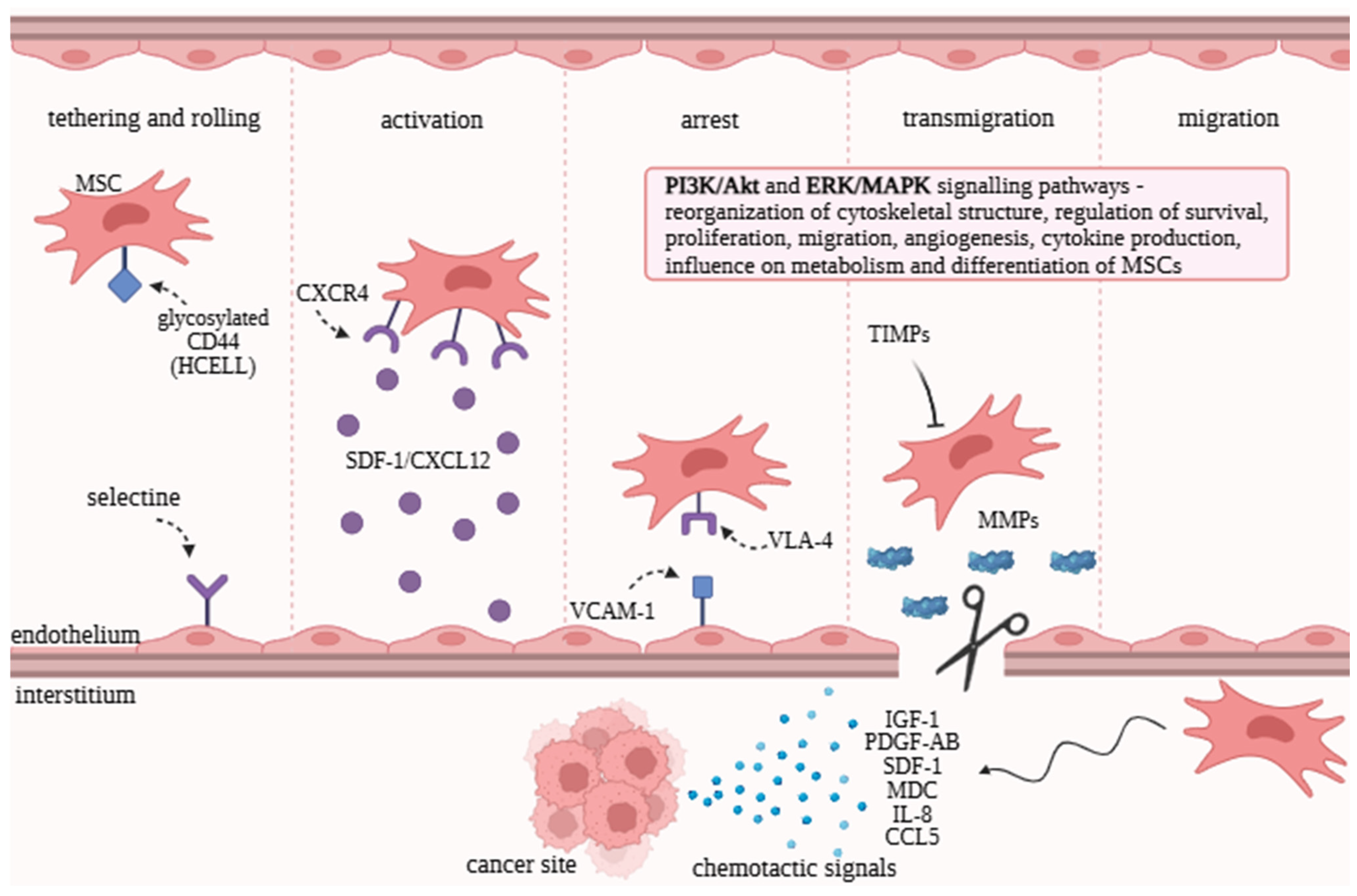

2.1. Tropism and Homing Abilities of MSCs

2.2. Signaling Pathways and Their Role in Regulating MSC Functions

2.3. Bidirectional Regulatory Roles of MSCs in Tumors

3. MSCs as Drug Carriers—Mechanisms of Drug Delivery by MSCs to Target Sites

4. Innovative Therapeutic Strategies Using MSCs

4.1. Delivery of Oncolytic Viruses by MSCs

4.2. Molecular Engineering Strategies to Improve the Anticancer Potential of MSCs

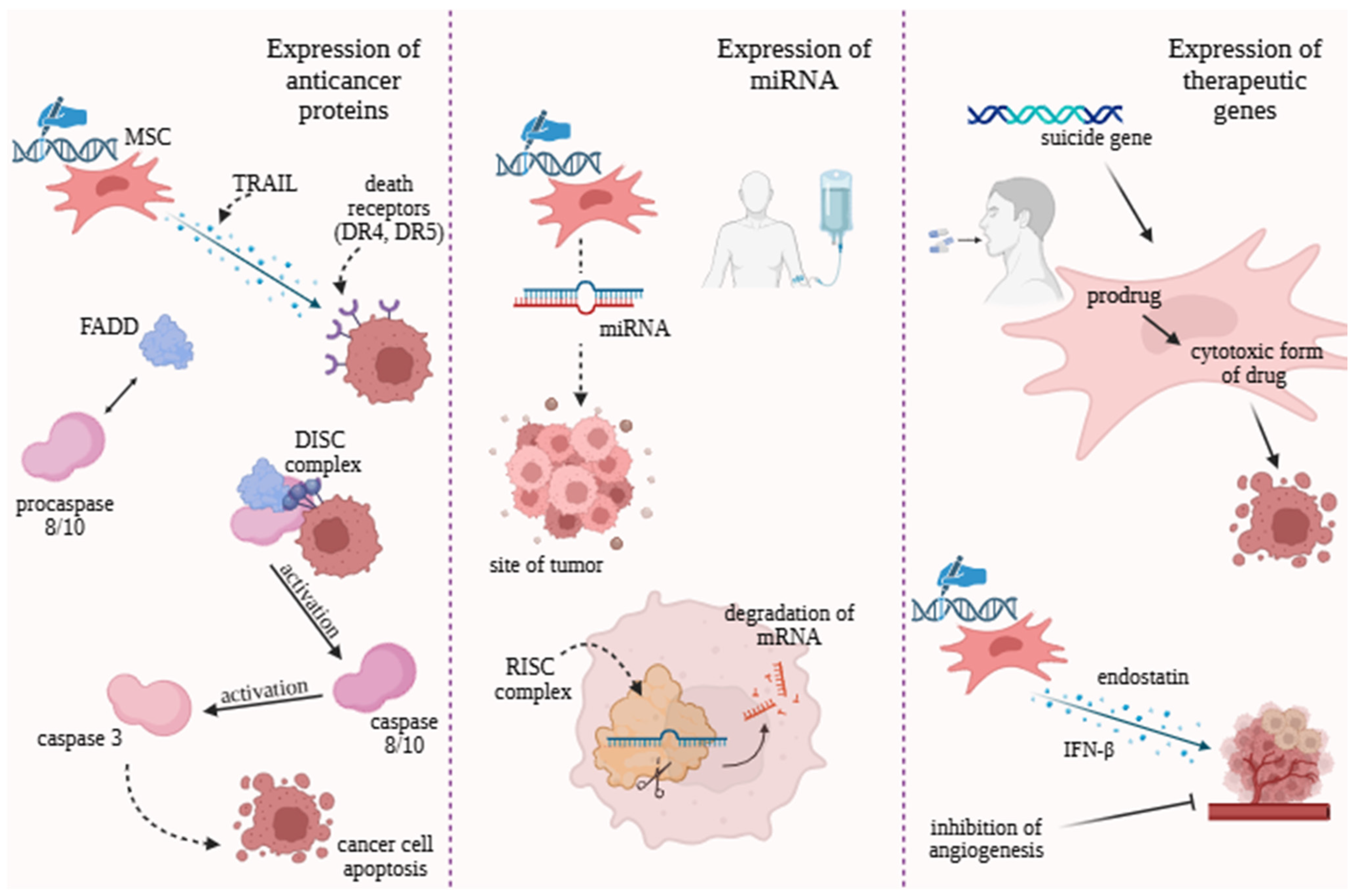

4.3. Expression of Anticancer Proteins

4.4. Engineering Strategies Based on Non-Coding RNAs Modulation

4.5. Therapeutic Genes

4.6. Advantages and Disadvantages of Various Innovative Therapeutic Strategies

5. Clinical Trials of MSCs in Cancer Therapy

6. Limitations and Challenges

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aCRC | Advanced colorectal cancer |

| AdV | Adenovirus |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukemia |

| AMSC | Allogenic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell |

| AT-MSC | Adipose tissue cell |

| AVVs | Adeno-associated viruses |

| BM-MSC | Bone marrow cells |

| CAA | Cancer-associated adipocyte |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| circRNA | Circular RNA |

| CCL5 | C–C motif chemokine ligand 5 |

| CCR-2 | C-C chemokine receptor type 2 |

| dCas9 | Catalytically deficient Cas9 |

| CD | Cytosine deaminase |

| CRAd | Conditionally replicative adenovirus |

| CRISPR/ Cas | Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats–associated protein |

| CRT | Calreticulin |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| CSF-1 | Colony-stimulating factor 1 |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

| CTXs | Chemotherapy |

| CXCL7 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 7 |

| CXCL10 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| CXCR4 | Chemokine receptor type 4 |

| CXCR3 | Chemokine receptor type 3 |

| CXCR7 | Chemokine receptor type 7 |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| DDS | Drug delivery system |

| DIPG | Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma |

| DISC | Death-inducing signaling complex |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DOX | Doxycycline |

| DSBs | Double-stranded breaks |

| DR | Death receptor |

| EAL | Early anastomotic leakage |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| Epo | Erythropoietin |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ES | Endostatin |

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| FADD | Fas-associated death domain |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| GCV | Ganciclovir |

| GDEPT | Gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy |

| gRNA | Guide ribonucleic acid |

| HB-adMSCs | Allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 |

| HLA-DR | Human leukocyte antigen—DR isotype |

| HMBG1 | High-mobility group box 1 |

| HMs | Hematological malignancies |

| hMSCs-INFb | Human mesenchymal stem cells with interferon beta |

| hPMSC–DE | Human placenta mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosome |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| HSPs | Heat shock proteins |

| HSV | Herpes simplex virus |

| HSVTK | Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase |

| hUC-MSC | Human umbilical-cord-derived mesenchymal stromal cell |

| IA | Intra-arterial |

| ICAM-1 | Intracellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| ICD | Immunogenic cell death |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| ILV | Intraluminal vesicles |

| LncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| IP | Intraperitoneal |

| IT | Intratumorally |

| IVI | Intravenous infusion |

| JAM-A | Junctional adhesion molecules-A |

| LAR | Low Anterior Resection |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MB | Medulloblastoma |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDC | Macrophage-derived chemokine |

| MHC II | Major histocompatibility complex type II |

| miRNA | Micro ribonucleic acid |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MMPs | Metalloproteinases |

| MMP-2 | Matrix metalloproteinase-2 |

| MMP-9 | Matrix metalloproteinase-9 |

| MSCs | Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells |

| MSCs-Des | Mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes |

| MSC-L | Mesenchymal stem cell-mobilizing lymphocytes |

| MTD | Maximum tolerated dose |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MV | Measles virus |

| MVB | Multivesicular bodies |

| Myo10 | Myosin 10 |

| MYXV | Myxoma virus |

| NDV | Newcastle disease virus |

| NK | Natural killer |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| NVB | Neuro-vascular bundle |

| OAd | Oncolytic adenovirus |

| OVs | Oncolytic viruses |

| OR | Operating room |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PB-MSCs | Peripheral blood cells |

| PCa | Prostate cancer |

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PDGF | Platelet-derived growth factor |

| PDGF-AB | Platelet-derived growth factor-AB |

| PDK1 | 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 |

| PDL | Programmed death ligand |

| PGF | Placental growth factor |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide-3-kinase |

| PSGL-1 | P-selectin ligand |

| rGBM | Recurrent glioblastoma |

| rHGG | Recurrent high-grade glioma |

| RC | Rectal cancer |

| RISC | RNA-induced silencing complex |

| RNAi | RNA interfering |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SDF-1 | Stromal cell-derived factor-1 |

| siRNA | Small interfering ribonucleic acid |

| ST | Solid tumors |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TAAs | Tumor-associated antigens |

| TA-MSCs | Tumor-associated mesenchymal stromal/stem cells |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor β |

| TIMPs | Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alfa |

| TNTs | Tunneling nanotubes |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| UCMSC-Exo | Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells exosomes |

| VACV | Vaccinia virus |

| VEGFR1 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VLA-4 | Very late antigen-4 |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| ZFNs | Zinc-finger nucleases |

| 5-FC | 5-flucytosine |

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Zugazagoitia, J.; Guedes, C.; Ponce, S.; Ferrer, I.; Molina-Pinelo, S.; Paz-Ares, L. Current challenges in cancer treatment. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 1551–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debela, D.T.; Muzazu, S.G.; Heraro, K.D.; Ndalama, M.T.; Mesele, B.W.; Haile, D.C.; Kitui, S.K.; Manyazewal, T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211034366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma, V.V. An overview of targeted cancer therapy. BioMedicine 2015, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lin, R.; Wu, H.; Jiang, X.; Gao, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Living Carrier for Active Tumor-Targeted Delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 185, 114300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: Cell biology to clinical progress. npj Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Luo, M.; Wei, X. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in cancer therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naji, A.; Eitoku, M.; Favier, B.; Deschaseaux, F.; Rouas-Freiss, N.; Suganuma, N. Biological Functions of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Clinical Implications. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 3323–3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.K.; Shih, H.-H.; Parveen, F.; Lenzen, D.; Ito, E.; Chan, T.-F.; Ke, L.-Y. Identifying the therapeutic significance of mesenchymal stem cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass, R.; Kasper, C.; Böhm, S.; Jacobs, R. Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): A comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Commun. Signal. 2011, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.C.; Krause, D.S.; Deans, R.J.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E.M. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, S.; Shi, Y.; Galipeau, J.; Krampera, M.; Leblanc, K.; Martin, I.; Nolta, J.; Phinney, D.G.; Sensebe, L. Mesenchymal stem versus stromal cells: International Society for Cell & Gene Therapy (ISCT®) Mesenchymal Stromal Cell committee position statement on nomenclature. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 1019–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdasi, S.; Viswanathan, C.; Kulkarni, R.; Bopardikar, A. Comparison of cancer cell tropism of various mesenchymal stem cell types. J. Stem Cells 2018, 13, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Cao, X.; Zhou, B.; Mei, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Yao, Y.; Wang, M. Tumor-associated mesenchymal stem/stromal cells in tumor microenvironment and carcinogenesis. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.A.W.; Lam, P.Y.P. Signaling molecules and pathways involved in MSC tumor tropism. Histol. Histopathol. 2013, 28, 1427–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosu, A.; Ghaemi, B.; Bulte, J.W.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. Tumor-tropic Trojan horses: Using mesenchymal stem cells as cellular nanotheranostics. Theranostics 2024, 14, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Fan, Q.; Peng, X.; Yang, S.; Wei, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, L.; Li, H. Mesenchymal/stromal stem cells: Necessary factors in tumour progression. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjad, U.; Ahmed, M.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Riaz, M.; Mustafa, M.; Biedermann, T.; Klar, A.S. Exploring mesenchymal stem cells homing mechanisms and improvement strategies. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2024, 13, 1161–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzsche, F.; Müller, C.; Lukomska, B.; Jolkkonen, J.; Deten, A.; Boltze, J. Concise review: MSC adhesion cascade—Insights into homing and transendothelial migration. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 1446–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Liu, D.D.; Thakor, A.S. Mesenchymal stromal cell homing: Mechanisms and strategies for improvement. iScience 2019, 15, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Yu, S.; Lin, J.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.; Yang, L. Bioactive materials that promote the homing of endogenous mesenchymal stem cells to improve wound healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 7751–7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Becker, A.; Van Riet, I. Homing and migration of mesenchymal stromal cells: How to improve the efficacy of cell therapy? World J. Stem Cells 2016, 8, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohni, A.; Verfaillie, C.M. Mesenchymal stem cells migration homing and tracking. Stem Cells Int. 2013, 2013, 130763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, J.E.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhang, L.; Pratt, R.E.; Dzau, V.J. Mesenchymal stem cells use integrin β1 not CXC chemokine receptor 4 for myocardial migration and engraftment. Mol. Biol. Cell 2007, 18, 2873–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ries, C.; Egea, V.; Karow, M.; Kolb, H.; Jochum, M.; Neth, P. MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and TIMP-2 are essential for the invasive capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells: Differential regulation by inflammatory cytokines. Blood 2007, 109, 4055–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samakova, A.; Gazova, A.; Sabova, N.; Valaskova, S.; Jurikova, M.; Kyselovic, J. The PI3K/Akt Pathway Is Associated with Angiogenesis, Oxidative Stress and Survival of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Pathophysiologic Condition in Ischemia. Physiol. Res. 2019, 68, S131–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Crawford, R.; Chen, C.; Xiao, Y. The Key Regulatory Roles of the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in the Functionalities of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Applications in Tissue Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 516–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Dai, Y.; Qian, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; He, Q.; Zhang, H. DKK1 Activates the PI3K/AKT Pathway via CKAP4 to Balance the Inhibitory Effect on Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling and Regulates Wnt3a-Induced MSC Migration. Stem Cells 2024, 42, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, N.; Al Saihati, H.A.; Alali, Z.; Aleniz, F.Q.; Mahmoud, S.Y.M.; Badr, O.A.; Dessouky, A.A.; Mostafa, O.; Hussien, N.I.; Farid, A.S.; et al. Exploring the Molecular Mechanisms of MSC-Derived Exosomes in Alzheimer’s Disease: Autophagy, Insulin and the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Pan, W.W.; Liu, S.B.; Shen, Z.F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.L. ERK/MAPK Signalling Pathway and Tumorigenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ruan, M.; Bu, Q.; Zhao, C. Signaling Pathways Driving MSC Osteogenesis: Mechanisms, Regulation, and Translational Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.-Z.; Liu, T.; Feng, X.; Yang, N.; Zhou, H.-F. Signaling Pathway of MAPK/ERK in Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, Migration, Senescence and Apoptosis. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. 2015, 35, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Bian, C.; Li, J.; Du, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, R.C. miR-21 Modulates the ERK–MAPK Signaling Pathway by Regulating SPRY2 Expression during Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 1374–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.M.; Yuan, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.N.; Kong, X.; Zheng, F.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L.; Guo, L.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; et al. Acetylcholine Induces Mesenchymal Stem Cell Migration via Ca2+/PKC/ERK1/2 Signal Pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 2704–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, Y.; Ah-Pine, F.; Khettab, M.; Arcambal, A.; Begue, M.; Dutheil, F.; Gasque, P. The Dual Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Cancer Pathophysiology: Pro-Tumorigenic Effects versus Therapeutic Potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrell, C.R.; Volarevic, A.; Djonov, V.G.; Jovicic, N.; Volarevic, V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell: A Friend or Foe in Anti-Tumor Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Xia, X.; Yao, M.; Yang, Y.; Ao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, X. The Dual Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Apoptosis Regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.Y.; Kwon, M.; Choi, H.E.; Kim, K.S. Recent advances in transdermal drug delivery systems: A review. Biomater. Res. 2021, 25, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Allabun, S.; Ojo, S.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Shukla, P.K.; Abbas, M.; Wechtaisong, C.; Almohiy, H.M. Enhanced drug delivery system using mesenchymal stem cells and membrane-coated nanoparticles. Molecules 2023, 28, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tashima, T. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-based drug delivery into the brain across the blood–brain barrier. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Shi, C. MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Roles and Molecular Mechanisms for Tissue Repair. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 7953–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayat Pisheh, H.; Sani, M. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived Exosomes: A New Era in Cardiac Regeneration. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Rajendran, R.L.; Chatterjee, G.; Reyaz, D.; Prakash, K.; Hong, C.M.; Ahn, B.C.; ArulJothi, K.N.; Gangadaran, P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: A Paradigm Shift in Clinical Therapeutics. Exp. Cell Res. 2025, 450, 114616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, K.; Cao, Q.; Liu, T.; Li, J. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes for drug delivery. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Mukhopadhyay, C.D. Exosome as drug delivery system: Current advancements. Extracell. Vesicle 2024, 3, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Hassanpour, M.; Rezaie, J. Engineered extracellular vesicles: A novel platform for cancer combination therapy and cancer immunotherapy. Life Sci. 2022, 308, 120935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Fatima, F. Extracellular vesicles, tunneling nanotubes, and cellular interplay: Synergies and missing links. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, R.; Belian, S.; Zurzolo, C. Hijacking intercellular trafficking for the spread of protein aggregates in neurodegenerative diseases: A focus on tunneling nanotubes (TNTs). Extracell. Vesicles Circ. Nucleic Acids 2023, 4, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formicola, B.; D’Aloia, A.; Dal Magro, R.; Stucchi, S.; Rigolio, R.; Ceriani, M.; Re, F. Differential exchange of multifunctional liposomes between glioblastoma cells and healthy astrocytes via tunneling nanotubes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; He, Y.; Fan, C.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, W. Mitochondrial Transfer in Tunneling Nanotubes—A New Target for Cancer Therapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierri, G.; Saenz-de-Santa-Maria, I.; Renda, A.; Koch, M.; Sommi, P.; Anselmi-Tamburini, U.; Mauri, M.; d’Aloia, A.; Ceriani, M.; Salerno, D.; et al. Nanoparticle Shape Is the Game-Changer for Blood–Brain Barrier Crossing and Delivery through Tunneling Nanotubes among Glioblastoma Cells. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yang, X.; Zheng, H.; Chen, C.; Yuan, J. Role of tunneling nanotubes in neuroglia. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 21, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hmadcha, A.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Gauthier, B.R.; Soria, B.; Capilla-Gonzalez, V. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, T. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in cancer therapy resistance: Recent advances and therapeutic potential. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coccè, V.; Farronato, D.; Brini, A.T.; Masia, C.; Giannì, A.B.; Piovani, G.; Sisto, F.; Alessandri, G.; Angiero, F.; Pessina, A. Drug loaded gingival mesenchymal stromal cells (GinPa-MSCs) inhibit in vitro proliferation of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacioni, S.; D’Alessandris, Q.G.; Giannetti, S.; Morgante, L.; De Pascalis, I.; Coccè, V.; Bonomi, A.; Pascucci, L.; Alessandri, G.; Pessina, A.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells loaded with paclitaxel induce cytotoxic damage in glioblastoma brain xenografts. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015, 6, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, F.A.; Irani, S.; Oloomi, M.; Bolhassani, A.; Geranpayeh, L.; Atyabi, F. Doxorubicin loaded exosomes inhibit cancer-associated fibroblasts growth: In vitro and in vivo study. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, S.; Guo, J.; Alahdal, M.; Cao, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, F.; Shen, Y.; Sun, M.; Mo, R.; et al. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin by nano-loaded mesenchymal stem cells for lung melanoma metastases therapy. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, E.; Abnous, K.; Farzad, S.A.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Targeted doxorubicin-loaded mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes as a versatile platform for fighting against colorectal cancer. Life Sci. 2020, 261, 118369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Song, Z. Targeting the tumor microenvironment with mesenchymal stem cells based delivery approach for efficient delivery of anticancer agents: An updated review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 232, 116725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, Y.; Kusamori, K.; Nishikawa, M. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells as next-generation drug delivery vehicles for cancer therapeutics. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2021, 18, 1627–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Y. Maximized nanodrug-loaded mesenchymal stem cells by a dual drug-loaded mode for the systemic treatment of metastatic lung cancer. Drug Deliv. 2017, 24, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, Y.; Kamino, R.; Hirabayashi, S.; Kishimoto, T.; Kanbara, H.; Danjo, S.; Hosokawa, M.; Ogawara, K.I. Efficient Liposome Loading onto Surface of Mesenchymal Stem Cells via Electrostatic Interactions for Tumor-Targeted Drug Delivery. Biomedicines 2023, 14, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, T.; Gao, M.; Liu, B.; Zhang, X.; Wu, F. Recent developments of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in respiratory system diseases: A review. Medicine 2025, 104, e43416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, L.; Zhong, Y.; Xu, Q.; Yan, J.; Pan, D.; Xu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; et al. Impact of mesenchymal stem cell size and adhesion modulation on in vivo distribution: Insights from quantitative PET imaging. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Lu, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, R.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Q.; Wei, Z.; et al. Thermosensitive hydrogel as a sustained release carrier for mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles in the treatment of intrauterine adhesion. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Chen, L.; Gao, X.; Sun, X.; Jin, G.; Yang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, G. Comparison of Different Sources of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Focus on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 1721–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, R.; Wan, Z.; Yang, C.; Shen, X.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Su, H. Advances and clinical challenges of mesenchymal stem cell therapy. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1421854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Chinchilla, J.I.; Zapata, A.G.; Moraleda, J.M.; García-Bernal, D. Bioengineered Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Anti-Cancer Therapy: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Sun, X.; Su, C.; Xue, Y.; Song, X.; Deng, R. Macrophages–Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells Crosstalk in Bone Healing. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1193765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, K.S.; Piperi, C.; Korkolopoulou, P. Clinical Applications of Adipose-Derived Stem Cell (ADSC) Exosomes in Tissue Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segunda, M.N.; Díaz, C.; Torres, C.G.; Parraguez, V.H.; De los Reyes, M.; Peralta, O.A. Bovine Peripheral Blood-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells (PB-MSCs) and Spermatogonial Stem Cells (SSCs) Display Contrasting Expression Patterns of Pluripotency and Germ Cell Markers under the Effect of Sertoli Cell Conditioned Medium. Animals 2024, 14, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.-L.; Li, J.; Chen, G.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhang, C.-H. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Peripheral Blood Retain Their Pluripotency, but Undergo Senescence during Long-Term Culture. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2015, 21, 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfy, A.; El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; Cuthbert, R.; Jones, E.; Badawy, A. Comparative Study of Biological Characteristics of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolated from Mouse Bone Marrow and Peripheral Blood. Biomed. Rep. 2019, 11, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, G. Circulating Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Clinical Implications. J. Orthop. Transl. 2014, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Feng, C.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y.; Fang, J. Engineered mesenchymal stem/stromal cells against cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, Z.; Ferdous, U.T.; Nzila, A.; Easmin, F.; Shakoor, A.; Zia, A.W.; Uddin, S. Stem Cell for Cancer Immunotherapy: Current Approaches and Challenges. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2025, 21, 1931–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Suryaprakash, S.; Lao, Y.-H.; Leong, K.W. Engineering mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine and drug delivery. Methods 2015, 84, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Genetically modified mesenchymal stem cell therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabdallah, B.F.; Allard, E.; Yao, S.; Friedman, G.; Gregory, P.D.; Eliopoulos, N.; Fradette, J.; Spees, J.L.; Haddad, E.; Holmes, M.C.; et al. Targeted gene addition to human mesenchymal stromal cells as a cell-based plasma-soluble protein delivery platform. Cytotherapy 2010, 12, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimentel, J.M.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Wu, G.S. The role of TRAIL in apoptosis and immunosurveillance in cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, K.; Yamahara, K.; Ohnishi, S.; Obata, H.; Kitamura, S.; Nagaya, N. Nonviral delivery of siRNA into mesenchymal stem cells by a combination of ultrasound and microbubbles. J. Control. Release 2009, 133, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muroski, M.E.; Morgan, T.J., Jr.; Levenson, C.W.; Strouse, G.F. A gold nanoparticle pentapeptide: Gene fusion to induce therapeutic gene expression in mesenchymal stem cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14763–14771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-X.; Wong, J.C. Mission impossible: Mesenchymal stem cells delivering oncolytic viruses before self-destruction. Mol. Ther. Oncol. 2025, 33, 200943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, F.; Soltanmohammadi, F.; Fayeghi, T.; Farajnia, S.; Alizadeh, E. Preventing MSC aging and enhancing immunomodulation: Novel strategies for cell-based therapies. Regen. Ther. 2025, 29, 517–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleh, H.E.G.; Vakilzadeh, G.; Zahiri, A.; Farzanehpour, M. Investigating the potential of oncolytic viruses for cancer treatment via MSC delivery. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; McFadden, G. Oncolytic viruses: Newest frontier for cancer immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi Darestani, N.; Gilmanova, A.I.; Al-Gazally, M.E.; Zekiy, A.O.; Ansari, M.J.; Zabibah, R.S.; Jawad, M.A.; Al-Shalah, S.A.; Rizaev, J.A.; Alnassar, Y.S.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-released oncolytic virus: An innovative strategy for cancer treatment. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Sun, T.-K.; Chen, M.-S.; Munir, M.; Liu, H.-J. Oncolytic viruses-modulated immunogenic cell death, apoptosis and autophagy linking to virotherapy and cancer immune response. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1142172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fretwell, E.C.; Houldsworth, A. Oncolytic Virus Therapy in a New Era of Immunotherapy, Enhanced by Combination with Existing Anticancer Therapies: Turn Up the Heat! J. Cancer 2025, 16, 1782–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, V.; Vescovini, R.; Dessena, M.; Donofrio, G.; Storti, P.; Giuliani, N. Oncolytic Viruses: A Potential Breakthrough Immunotherapy for Multiple Myeloma Patients. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1483806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Liu, C.; An, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Xia, Q. Mechanisms of Oncolytic Virus-Induced Multi-Modal Cell Death and Therapeutic Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Wang, Z. Strategies for Engineering Oncolytic Viruses to Enhance Cancer Immunotherapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1450203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Esmaeili Gouvarchin Ghaleh, H.; Farzanehpour, M.; Dorostkar, R.; Jalali Kondori, B.; Bolandian, M. Oncolytic Viruses and Cancer, Do You Know the Main Mechanism? Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 761015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Yan, Y.; Yang, C.; Cai, H. Immunogenic Cell Death and Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer: Mechanisms, Synergies, and Innovative Therapeutic Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucikova, J.; Kepp, O.; Kasikova, L.; Petroni, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Spisek, R.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.S.; Liu, Z.; Bartlett, D.L. Oncolytic immunotherapy: Dying the right way is a key to eliciting potent antitumor immunity. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasiya, S.; Chen, N.G.; Fong, Y. Oncolytic viruses and immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2018, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duebgen, M.; Martinez-Quintanilla, J.; Tamura, K.; Hingtgen, S.; Redjal, N.; Wakimoto, H.; Shah, K. Stem cells loaded with multimechanistic oncolytic herpes simplex virus variants for brain tumor therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.S.; Miri, S.M.; Dianat-Moghadam, H.; Ghorbanhosseini, S.S.; Mohebbi, S.R.; Keyvani, H.; Ghaemi, A. Oncolytic Newcastle disease virus delivered by Mesenchymal stem cells-engineered system enhances the therapeutic effects altering tumor microenvironment. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkisova, V.A.; Dalina, A.A.; Neymysheva, D.O.; Zenov, M.A.; Ilyinskaya, G.V.; Chumakov, P.M. Cell Carriers for Oncolytic Virus Delivery: Prospects for Systemic Administration. Cancers 2025, 17, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Fajardo, C.A.; Farrera-Sal, M.; Perisé-Barrios, A.J.; Morales-Molina, A.; Al-Zaher, A.A.; García-Castro, J.; Alemany, R. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of Oncolytic adenovirus–loaded menstrual blood–derived Mesenchymal stem cells in combination with peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Quintanilla, J.; Seah, I.; Chua, M.; Shah, K. Oncolytic viruses: Overcoming translational challenges. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, H.; He, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, P.; Mao, Q.; Xia, H. Systemic administration of mesenchymal stem cells loaded with a novel oncolytic adenovirus carrying IL-24/endostatin enhances glioma therapy. Cancer Lett. 2021, 509, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Castro, J.; Alemany, R.; Cascallo, M.; Martínez-Quintanilla, J.; del Mar Arriero, M.; Lassaletta, A.; Madero, L.; Ramirez, M. Treatment of metastatic neuroblastoma with systemic oncolytic virotherapy delivered by autologous mesenchymal stem cells: An exploratory study. Cancer Gene Ther. 2010, 17, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, A.; Shams, F.; Karami, F. Advancing mesenchymal stem cell therapy with CRISPR/Cas9 for clinical trial studies. In Cell Biology and Translational Medicine, Volume 8: Stem Cells in Regenerative Medicine; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lin, Q.; Jin, S.; Gao, C. The CRISPR-Cas toolbox and gene editing technologies. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillary, V.E.; Ceasar, S.A. A review on the mechanism and applications of CRISPR/Cas9/Cas12/Cas13/Cas14 proteins utilized for genome engineering. Mol. Biotechnol. 2023, 65, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chehelgerdi, M.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Khorramian-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Shafieizadeh, M.; Mahmoudi, E.; Eskandari, F.; Rashidi, M.; Arshi, A.; Mokhtari-Farsani, A. Comprehensive review of CRISPR-based gene editing: Mechanisms, challenges, and applications in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazrati, A.; Malekpour, K.; Soudi, S.; Hashemi, S.M. CRISPR/Cas9-engineered mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their extracellular vesicles: A new approach to overcoming cell therapy limitations. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.R.; Shin, H.R.; Kweon, J.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, E.-Y.; Chang, E.-J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.W. Highly efficient genome editing via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery in mesenchymal stem cells. BMB Rep. 2024, 57, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayarsaikhan, D.; Poletto, E. Editorial: Genome Editing in Stem Cells. Front. Genome Ed. 2024, 6, 1357369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, C.; Xu, P. Base Editors-Mediated Gene Therapy in Hematopoietic Stem Cells for Hematologic Diseases. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2024, 20, 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, F.; Ye, L. Epigenetic Control of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Orchestrates Bone Regeneration. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjaltema, R.A.F.; Rots, M.G. Advances of Epigenetic Editing. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 57, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, A.; McClements, M.E.; MacLaren, R.E. CRISPR-Cas9 DNA Base-Editing and Prime-Editing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.U.; Yoon, Y.; Jung, P.Y.; Hwang, S.; Hong, J.E.; Kim, W.-S.; Sohn, J.H.; Rhee, K.-J.; Bae, K.S.; Eom, Y.W. TRAIL-overexpressing adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells efficiently inhibit tumor growth in an H460 xenograft model. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2021, 18, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisendi, G.; Dall’Ora, M.; Casari, G.; Spattini, G.; Farshchian, M.; Melandri, A.; Masciale, V.; Lepore, F.; Banchelli, F.; Costantini, R.C.; et al. Combining gemcitabine and MSC delivering soluble TRAIL to target pancreatic adenocarcinoma and its stroma. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Liu, T.; Miao, L.; Ji, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X. Cisplatin-encapsulated TRAIL-engineered exosomes from human chorion-derived MSCs for targeted cervical cancer therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik Fakiruddin, K.; Ghazalli, N.; Lim, M.N.; Zakaria, Z.; Abdullah, S. Mesenchymal stem cell expressing TRAIL as targeted therapy against sensitised tumour. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ticona-Pérez, F.V.; Chen, X.; Pandiella, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, E. Multiple mechanisms contribute to acquired TRAIL resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kureshi, C.T.; Dougan, S.K. Cytokines in cancer. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kułach, N.; Pilny, E.; Cichoń, T.; Czapla, J.; Jarosz-Biej, M.; Rusin, M.; Drzyzga, A.; Matuszczak, S.; Szala, S.; Smolarczyk, R. Mesenchymal stromal cells as carriers of IL-12 reduce primary and metastatic tumors of murine melanoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Ryu, C.H.; Kim, M.J.; Jeun, S.-S. Combination therapy for gliomas using temozolomide and interferon-beta secreting human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2015, 57, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Kumar, S.; Chanda, D.; Chen, J.; Mountz, J.D.; Ponnazhagan, S. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells producing interferon-α in a mouse melanoma lung metastasis model. Stem Cells 2008, 26, 2332–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Huang, W.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Geng, Q.; Fan, H.; Tan, Y.; Xue, G.; Jiang, X. In vitro effect of adenovirus-mediated human Gamma Interferon gene transfer into human mesenchymal stem cells for chronic myelogenous leukemia. Hematol. Oncol. 2006, 24, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhasani, S.; Ahmadi, Y.; Rostami, Y.; Fattahi, D. The role of MicroRNAs in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation into vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Div. 2025, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmizrak, A.; Dalmizrak, O. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as new tools for delivery of miRNAs in the treatment of cancer. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 956563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaraman, A.K.; Babu, M.A.; Afzal, M.; Sanghvi, G.; MM, R.; Gupta, S.; Rana, M.; Ali, H.; Goyal, K.; Subramaniyan, V.; et al. Exosome-based miRNA delivery: Transforming cancer treatment with mesenchymal stem cells. Regen. Ther. 2025, 28, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R.; Kasinski, A.L.; Shen, H.; Slack, F.J.; Tang, D.G. MicroRNA-34a: Potent tumor suppressor, cancer stem cell inhibitor, and potential anticancer therapeutic. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 640587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Ren, Z.J.; Tang, J.H. MicroRNA-34a: A potential therapeutic target in human cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, C.; Cai, L.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Su, Z.; Lu, X. miR-34a derived from mesenchymal stem cells stimulates senescence in glioma cells by inducing DNA damage. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 1849–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawati, I.; Liu, M.-C.; Hsieh, C.-L.; Do, A.D.; Sung, S.-Y. Targeting castration-resistant prostate cancer using mesenchymal stem cell exosomes for therapeutic MicroRNA-let-7c delivery. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2022, 27, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, V.; Kessenbrock, K.; Lawson, D.; Bartelt, A.; Weber, C.; Ries, C. Let-7f miRNA regulates SDF-1α-and hypoxia-promoted migration of mesenchymal stem cells and attenuates mammary tumor growth upon exosomal release. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, N.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, D.; Lin, R.; Wang, X.; Shi, B. Anticancer effects of miR-124 delivered by BM-MSC derived exosomes on cell proliferation, epithelial mesenchymal transition, and chemotherapy sensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells. Aging 2020, 12, 19660–19676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Lin, Y.-Q.; Ye, H.-Y.; Lin, W.-M. miR-124 delivered by BM-MSCs-derived exosomes targets MCT1 of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells and improves ovarian cancer immunotherapy. Neoplasma 2023, 70, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lai, X.; Yue, Q.; Cao, F.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tian, J.; Lu, Y.; He, L.; Bai, J.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomal microRNA-16-5p restrains epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells via EPHA1/NF-κB signaling axis. Genomics 2022, 114, 110341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, D.; Bi, Y.; Liu, S. The emerging roles of exosomal miRNAs in breast cancer progression and potential clinical applications. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2023, 15, 825–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheykhhasan, M.; Kalhor, N.; Sheikholeslami, A.; Dolati, M.; Amini, E.; Fazaeli, H. Exosomes of mesenchymal stem cells as a proper vehicle for transfecting miR-145 into the breast cancer cell line and its effect on metastasis. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 5516078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Gan, C.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Feng, L. A comprehensive review of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs): Mechanism, therapeutic targets, and delivery strategies for cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 7605–7635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali Zaidi, S.S.; Fatima, F.; Ali Zaidi, S.A.; Zhou, D.; Deng, W.; Liu, S. Engineering siRNA therapeutics: Challenges and strategies. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubanako, P.; Mirza, S.; Ruff, P.; Penny, C. Exosome-mediated delivery of siRNA molecules in cancer therapy: Triumphs and challenges. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1447953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Cui, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Wu, M.; Wei, X.; Lai, Y.; Mi, P. Bioengineered nanovesicles for efficient siRNA delivery through ligand-receptor-mediated and enzyme-controlled membrane fusion. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, R.; LeBleu, V.S.; Lee, J.J.; Smaglo, B.G.; Zhao, D.; Lee, M.S.; Wolff, R.A.; Overman, M.J.; Mendt, M.C.; McAndrews, K.M.; et al. Phase I study of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes with KRASG12D siRNA in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer harboring a KRASG12D mutation. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, TPS633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, B.; Fan, J.; Xue, C.; Lu, Y.; Li, C.; Cui, D. Engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes with high CXCR4 levels for targeted siRNA gene therapy against cancer. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 4098–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Richards, A.M. Effective tools for RNA-derived therapeutics: siRNA interference or miRNA mimicry. Theranostics 2021, 11, 8771–8796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Yao, Y.N.; Zhou, S.A.; Wang, Y. Regulation and Intervention of Stem Cell Differentiation by Long Non-Coding RNAs: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. World J. Stem Cells 2025, 17, 107688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Yi, Y.; Mei, Z.; Huang, D.; Tang, S.; Hu, L.; Liu, L. Circular RNAs in Cancer Stem Cells: Insights into Their Roles and Mechanisms (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 55, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.-W.; Liu, C.-G.; Kirby, J.A.; Chu, C.; Zang, D.; Chen, J. The Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicle-Derived lncRNAs and circRNAs in Tumor and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: The Biological Functions and Potential for Clinical Application. Cancers 2025, 17, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, E.; Jiang, Y.; Kristensen, L.S.; Hansen, T.B.; Kjems, J. The Therapeutic Potential of Circular RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2025, 26, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjoo, Z.; Chen, X.; Hatefi, A. Progress and problems with the use of suicide genes for targeted cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 99, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibensky, M.; Jakubechova, J.; Altanerova, U.; Pastorakova, A.; Rychly, B.; Baciak, L.; Mravec, B.; Altaner, C. Gene-directed enzyme/prodrug therapy of rat brain tumor mediated by human mesenchymal stem cell suicide gene extracellular vesicles in vitro and in vivo. Cancers 2022, 14, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorakova, A.; Jakubechova, J.; Altanerova, U.; Altaner, C. Suicide gene therapy mediated with exosomes produced by mesenchymal stem/stromal cells stably transduced with HSV thymidine kinase. Cancers 2020, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Wei, Y.; Zhao, X. Antitumor activities of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells expressing endostatin on ovarian cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Guo, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, D.; Sun, L.; Liang, T.; Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, G. Endostatin-expressing endometrial mesenchymal stem cells inhibit angiogenesis in endometriosis through the miRNA-21-5p/TIMP3/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2025, 14, szae079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogiatzi, I.; Lama, L.M.; Lehmann, A.; Rossignoli, F.; Gettemans, J.; Shah, K. Allogeneic stem cells engineered to release interferon β and scFv-PD1 target glioblastoma and alter the tumor microenvironment. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Singh, A.K.; Kannan, S.; Kolkundkar, U.; Seetharam, R.N. Therapeutic applications of engineered mesenchymal stromal cells for enhanced angiogenesis in cardiac and cerebral ischemia. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2024, 20, 2138–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.S.Y.; Tan, E.W.; Goh, B.H. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapies: Challenges and Enhancement Strategies. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Yuan, Z.; Weng, J.; Pei, D.; Du, X.; He, C.; Lai, P. Challenges and advances in clinical applications of mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitbon, A.; Delmotte, P.R.; Pistorio, V.; Halter, S.; Gallet, J.; Gautheron, J.; Monsel, A. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles therapy openings new translational challenges in immunomodulating acute liver inflammation. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Griensven, M.; Balmayor, E.R. Extracellular vesicles are key players in mesenchymal stem cells’ dual potential to regenerate and modulate the immune system. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 207, 115203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokati, A.; Rahnama, M.A.; Jalali, L.; Hoseinzadeh, S.; Masoudifar, S.; Ahmadvand, M. Revolutionizing cancer treatment: Engineering mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Fan, S.; Cao, M.; Liu, D.; Xuan, K.; Liu, A. Extracellular vesicles as drug delivery systems in therapeutics: Current strategies and future challenges. J. Pharm. Investig. 2024, 54, 785–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.L.; Huang, S.W.; Hsiao, A.C.; Chen, C.Y.; Hsu, K.F.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Liao, T.T. Harnessing engineered mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for innovative cancer treatments. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2025, 16, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Amjad, M.T.; Chidharla, A.; Kasi, A. Cancer Chemotherapy; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Brianna; Lee, S.H. Chemotherapy: How to reduce its adverse effects while maintaining the potency? Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartin, M.C.; Borzone, F.R.; Giorello, M.B.; Yannarelli, G.; Chasseing, N.A. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles as biological carriers for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 882545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, T.; Huang, T.; Gao, J. Current advances and challenges of mesenchymal stem cells-based drug delivery system and their improvements. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 600, 120477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta, C.T.; Ortiz, Y.Y.; Liu, Z.-J.; Velazquez, O.C. Methods and limitations of augmenting mesenchymal stem cells for therapeutic applications. Adv. Wound Care 2023, 12, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minev, T.; Balbuena, S.; Gill, J.M.; Marincola, F.M.; Kesari, S.; Lin, F. Mesenchymal stem cells-the secret agents of cancer immunotherapy: Promises, challenges, and surprising twists. Oncotarget 2024, 15, 793–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.R.; He, K.K.; Lokanathan, Y.; Gaurav, A.; Yusoff, K.; Macedo, M.F.; Bhassu, S. How Artificial Intelligence Can Enable Personalized Mesenchymal Stem Cell–Based Therapeutic Strategies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1654117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Dissanayaka, W.L.; Yiu, C.K.Y. Artificial Intelligence Driven Innovation: Advancing Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapies and Intelligent Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Drug Used in the Study | Source of Used MSCs | Reduction of Cancer Cells Viability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral squamous cell carcinoma | Paclitaxel, Doxorubicin, Gemcitabine | Gingival papillae | >90% | [55] |

| Glioblastoma | Paclitaxel | Mouse bone marrow | ~80% | [56] |

| Breast cancer | Doxorubicin | Adipose tissue | 43.3% | [57] |

| Melanoma with lung metastases | Nanoparticles with doxorubicin | Adipose tissue (mouse model) | ~55% (in vitro) ~60% (in vivo, metastases reduction) | [58] |

| Colon cancer | Doxorubicin | Mouse bone marrow | 65% | [59] |

| Feature | BM-MSCs [40,67,69,70] | AT-MSCs [18,67,69,71] | PB-MSCs [72,73,74,75] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | Invasive and painful tissue harvesting procedures compared to UC-MSC | Widespread availability, facile acquisition with minimal tissue disruption | High accessibility, minimally invasive, accessible via blood banks, no ethical concerns |

| Isolation and expansion | Ease of isolating, remarkable ability for in vitro expansion and multi-lineage differentiation | Uncomplicated isolation protocols, high proliferative efficiency | Low percentage of MSCs in steady state—difficult isolation and expansion, PB-MSCs had lower proliferative capacity than BM-MSCs |

| Immunogenicity | Low immunogenicity results from the absence of HLA-DR expression | Low immunogenicity reducing the risk of immune rejection—low expression of MHC II | MHC II negative, which may suggest a low ability to induce an immune response |

| Homing efficiency | Inherent homing properties identified as key enabler for widespread use | A strong ability to specifically migrate towards the tumor microenvironment and inflammatory sites | PB-MSCs homing is faster than BM-MSCs |

| Drug-loading capacity | High uptake, effective absorption of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, simple incubation | Similar capacity to BM-MSCs, confirmed absorption of anticancer drugs (cisplatin, paclitaxel) | No data |

| Type of miRNA | Effects of Actions | References |

|---|---|---|

| miR-34a | Fighting cancer stem cells, Relapse prevention; ↓ Tumor growth; ↓ Proliferation of cancer cells (50% after 72 h); ↑ DNA damage (6.5 times); ↓ Telomerase activity (~68%); ↑ Cancer cells’ senescence (percentage of senescent cells increased from ~8% to 72%) (glioma) | [130,131,132] |

| miR-let7 | ↓ Proliferation (10–30%) and migration of cancer cells (castration-resistant prostate cancer); ↓ Invasion (75–80%); ↓ Tumor growth (40%) (breast cancer, mouse model) | [133,134] |

| miR-124 | ↓ Invasion (75–80%) and migration (75%); ↓ EZH2 (oncogene) (65–75%) (pancreatic cancer); ↓ Immunosuppressive function of regulatory T cells, which enhances the immune response against cancer | [135,136] |

| miR-16 | ↓ Epithelial–mesenchymal transition; ↓ Invasion (50–70%); ↓ Tumor growth (tumor volume reduced by 50%, tumor weight by 47%) (breast cancer) | [137] |

| miR-342-3p | ↓ Metastasis (~45%) and chemoresistance (breast cancer) | [138] |

| miR-551b-3p | ↓ Cancer progression (breast cancer) | [138] |

| miR-21-5p | ↓ Invasiveness (breast cancer) | [138] |

| miR-3182 | ↑ Apoptosis and ↓ invasiveness of (triple negative breast cancer) | [138] |

| miR-148b-3p | ↓ Cancer progression (breast cancer) | [138] |

| miR-145 | ↑ Apoptosis (signal for cell death (tp53) was amplified 3–5 times) and ↓ metastasis (50-fold reduction in MMP9 levels) (breast cancer) | [139] |

| Study ID | Phase | Study Title | Intervention | MSC Source/Type | Cancer Type | Objective | Status of Study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04758533 | 1/2 | AloCELYVIR in DIPG in combination with radio- or MB in monotherapy | BM-hMSCs + AdV 500.000 cells/kg, Weekly IVI/8 week | BM-hMSCs | Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG), Medulloblastoma (MB) | Safety, Efficacy | Active, not recruiting | [69,165] |

| NCT03896568 | 1 | MSC-DNX-2401 in treating patients with rHGG | MSCs + OAd DNX-2401, IA | BM-hMSCs | High-Grade Glioma | Best dose, Side effects, Toxicity, Capacity, DNX-2401 delivery to rHGG | Recruiting | [69,165] |

| NCT03298763 | 1/2 | Targeted Stem Cells Expressing TRAIL as a Therapy for Lung Cancer | MSCTRAIL + pemetrexed/cisplatin | MSCs genetically modified to express TRAIL | Metastatic Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | Safety, Anti-tumor activity of MSCTRAIL in addition to CTX | Completed | [69,165] |

| NCT02530047 | 1 | Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) for Ovarian Cancer | MSC-INFb, 105 MSC/kg once a week for 4, IP | MSCs from healthy male donors and genetically changed | Ovarian cancer | Highest tolerable dose of MSC-INFb, Safety | Completed | [69,165] |

| NCT03608631 | 1 | iExosomes in Metastatic Pancreas Cancer With KrasG12D Mutation | MSCs-DEs + KrasG12D siRNA, IVI over 15–20 min. on 1 d, 4 d, and 10 d, every 14 days for up to 3 cycles | Not defined | Metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) with KrasG12D mutation | Best dose, Side effects | Recruiting | [69,165] |

| NCT05699811 | 1/2 | IFNα Expressing MSCs for Locally Advanced/Metastatic Solid Tumors | MSC-IFNα + paclitaxel /cyclophosphamide/ anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, IVI 1–4 times every 4–6 weeks (2 × 106 cells/kg) or 6 × 105 cells/ kg, 2 × 105/kg | hUC-MSCs | Locally advanced/metastatic ST: lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and sarcomas | Safety, Feasibility of MSC-IFNα | Recruiting | [165] |

| NCT04657315 | 1 | Evaluation of MTD, safety, and efficiency of MSC11FCD therapy to rGBM (MSC11FCD-GBM) | MSCs + suicide gene, CD (MSC11 FCD), i.t. 1 × 107, 3 × 107 cells, Concomitant 5-FC 150 mg/kg/day | Not defined | Glioblastoma | MTD, Safety, Efficiency | Completed | [165] |

| NCT06446050 | 1 | Chemokine and Costimulatory Molecule-modified MSCs for the treatment of aCRC | MSC-L, IV 1/2/3 × 106 cells/kg, every 21 days for at least 6 cycles of treatment | hUC-MSCs | Colorectal cancer | Safety, Efficacy | Recruiting | [165] |

| NCT06890494 | 1 | BiTE-EV therapy in Relapsed/ Refractory Acute B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia | EVs with BiTEs, and CD3+/CD19+ MSCs. Take BiTE-EV every other day for 1 or 2 months | Culture supernatant with the bispecific vesicles BiTE-EV (CD3, CD19) | Acute B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia | Safety, Efficacy, MTD | Recruiting | [165] |

| NCT06245746 | 1 | UCMSC-Exo in consolidation CTX-induced myelosuppression in AML | Single-time IVI | UCMSC-Exo | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Safety, Efficacy | Recruiting | [165] |

| NCT05789394 | 1 | Safety and preliminary efficacy of AMSCs for rGBM | IT received locally delivered AMSCs | AMSCs | Recurrent glioblastoma or astrocytoma | MTD, Safety, Preliminary efficacy | Recruiting | [165] |

| NCT07143812 | 1 | Suicide gene expressing BM-hMSCs (MSC11FCD) in patients with newly diagnosed GBM | 1 × 107, 3 × 107 cells IT or the tumor removal site using a syringe during surgery | BM-hMSCs | Glioblastoma | Safety, Tolerability, MTD | Not yet recruiting | [165] |

| NCT07048314 | 1/2 | HB-adMSCs in the recovery of erectile function post radical retropubic prostatectomy of localized PCa | HB-adMSCs injected into the corpora cavernosa bilateral NVB, OR week 1 + 2.00 × 108 via IV in clinic at week 12 | HB-adMSCs | Prostate Cancer | Safety, Efficacy | Not yet recruiting | [165] |

| NCT06536712 | 1 | IP EVs to prevent EAL in RC patients undergoing LAR | IP administered at the end of surgery | hPMSC-DE | Rectal Cancer | Safety, Efficacy | Not yet recruiting | [165] |

| NCT05672420 | 1/2 | UC-MSCs in treatment-induced myelosuppression in HMs (USMYE Trial) | 2 weeks of treatment: 5 dose-escalation levels and 3 frequency-escalation levels | UC-MSCs | Induced myelosuppression and acute myeloid leukemia/acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Safety, Efficacy | Completed | [165] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kucharczyk, H.; Tarnowski, M.; Tkacz, M. Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cancer Therapy: Advanced Therapeutic Strategies Towards Future Clinical Translation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4808. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244808

Kucharczyk H, Tarnowski M, Tkacz M. Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cancer Therapy: Advanced Therapeutic Strategies Towards Future Clinical Translation. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4808. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244808

Chicago/Turabian StyleKucharczyk, Hanna, Maciej Tarnowski, and Marta Tkacz. 2025. "Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cancer Therapy: Advanced Therapeutic Strategies Towards Future Clinical Translation" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4808. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244808

APA StyleKucharczyk, H., Tarnowski, M., & Tkacz, M. (2025). Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells (MSCs) in Cancer Therapy: Advanced Therapeutic Strategies Towards Future Clinical Translation. Molecules, 30(24), 4808. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244808