Wheat as a Storehouse of Natural Antimicrobial Compounds

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Wheat: History, Cultivation, and Global Significance

Structure and Chemical Composition of Wheat Grain

3. Antimicrobial Resistance and Natural Antimicrobials

4. Antimicrobial Compounds in Wheat

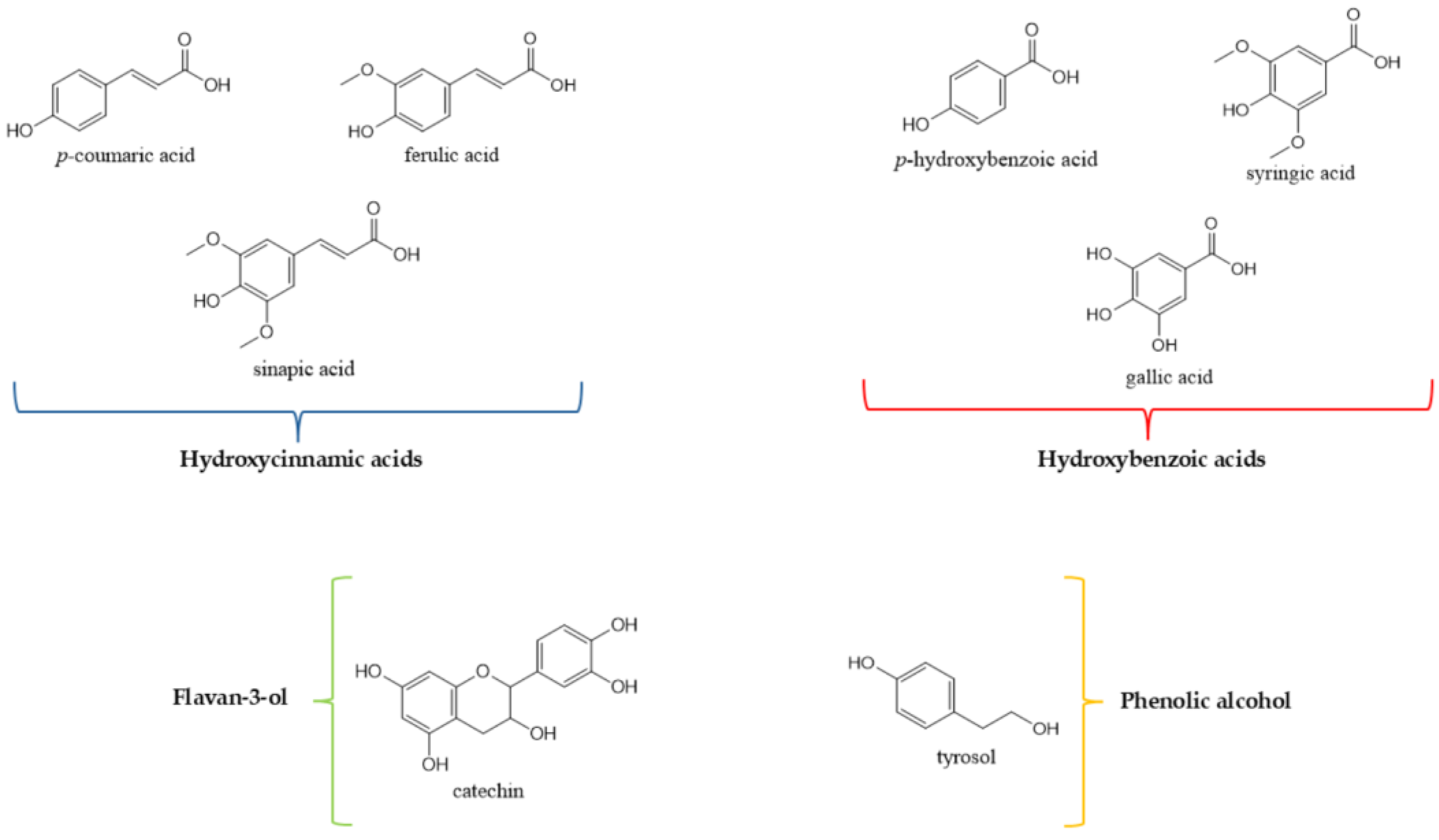

4.1. Polyphenols

4.2. Antimicrobial Peptides

| Wheat Variety | Bioactive Compounds | Target Microorganisms | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not available | p-coumaric acid | Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Salmonella typhimurium, and Shigella dysenteriae | MIC values ≈ 80 µg L−1 | [31] |

| Not available | Benzoic, p-hydroxybenzoic, p-coumaric, ferulic, and sinapic acids | Actinomyces viscosus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus salivarius, and Streptococcus sobrinus | Inhibition zone diameters ranged from 10–15 mm to 21–30 mm at doses between 1 and 5 mg/disc | [34] |

| Astoria, KWS Ozon, Kandela, and Torka | Ferulic and sinapic acids | Bacteria: Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Micrococcus luteus, and Proteus mirabilis Fungi: Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium graminearum, and Fusarium langsethiae | MIC values ranged from 0.20 to 2.86 µg/g extract. Lowest MIC values observed for Fusarium langsethiae 8051 | [36] |

| Kontesa, Torka, Hena, Helia, and Broma | Phenolic compounds | Fusarium culmorum | Treated cultures exhibited surface areas between 27.41 and 31.30 cm2, compared to 42.01 cm2 in control | [37] |

| North Dakota Common Emmer and hard red spring wheat cv. Barlow | Benzoic, gallic, protocatechuic, and ferulic acids and catechin | Helicobacter pylori | Inhibition zones observed at 72 h, ranging from 2 to 4 mm in width | [38] |

| Ancient wheat varieties: Ostro nudo, Antigola, Saragolla, and Primitivo Modern wheat varieties: Palesio, Bolero, Bologna, and Rebelde | Resorcinol, tyrosol and caffeic, syringic, and ferulic acids | Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica ser. Typhimurium, Enterobacter aerogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Enterococcus faecalis | The final optical density was significantly reduced at 630 nm after incubation with different sample extracts (0.19, 0.39, 1.56, 4.68 mg/mL) | [40] |

| Not available | Puroindolines | Staphylococcus aureus, Micrococcus lutius, Klebsiella, and Bacillus circus | Zone of inhibition ranged from 2 to 20 mm. Decreased protein concentration (from 3 mg/mL to 1 mg/mL) led to reduced inhibition zones | [45] |

| Not available | Puroindolines | Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Clavibacter michiganensis, Escherichia coli, Erwinia carotovora, Pseudomonas syringae, and Staphylococcus aureus | MICs ranged from 30 to 50 μg/mL | [47] |

| Not available | Puroindolines | Escherichia coli, Serratia marcenscens, and Staphylococcus aureus | At 1 mg/mL, the protein inhibited approximately 40–50% of microbial growth for all three species | [48] |

| Triticum aestivum L. cv. Chihoku komugi | Wheat multidomain cystatin (TaMDC1) | Bacteria: Pseudomonas syringae Fungi: Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria alternata | All TaMDC1-expressing plants displayed marked reduction in lesion size as compared to control plants | [52] |

| Not available | Wheat lipid transfer protein (TdLTP4) | Bacteria: Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermis, Enterococcus faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Fungi: Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus, Fusarium graminearum, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium culmorum, and Alternaria alternata. | Zone of inhibitions ranged from 14 to 26 mm, while MIC values were 62.5 µg mL−1 against Staphylococcus aureus, Fusarium graminearum, and Listeria monocytogenes. Other MIC values ranged from 125 to 250 µg mL−1 | [53] |

| Triticum durum L. cv. Altintoprak-98 | Wheat Antimicrobial Peptide (WAP) and Germinated Wheat Antimicrobial Peptide (GWAP) | Fungi: Botrytis cinerea, Fusarium oxysporum, Rhizoctonia solani, and Verticillium dahlia Bacteria: Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. sepedonicus and Erwinia carotovora subsp. carotovora | IC50 values of WAP and GWAP against fungi ranged from 20 to 40 μg cm−3 and 15 to 30 μg cm−3, respectively GWAP inhibited the growth of Clavibacter michiganensis at 180 μg protein cm−3 | [55] |

4.3. Other Antimicrobial Compounds in Wheat

5. Antimicrobial Properties of Wheat By-Products

6. Wheatgrass

7. Methodology

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMR | Antimicrobial resistance |

| RDA | Rural Development Administration |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| TaMDC1 | Wheat multidomain cystatin 1 |

| TdLTP4 | Wheat lipid transfer protein 4 |

| WAP | Wheat Antimicrobial Peptide |

| GWAP | Germinated Wheat Antimicrobial Peptide |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| PR-14 | Pathogenesis-Related Protein-14 |

| LTP | Lipid transfer proteins |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentration |

| MFC | Minimum fungicidal concentration |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| RP-HPLC | Reversed Phase-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| WBp-1 | Wheat Germ Agglutinin-Binding Protein 1 |

References

- Samreen; Ahmad, I.; Malak, H.A.; Abulreesh, H.H. Environmental antimicrobial resistance and its drivers: A potential threat to public health. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Wang, C.; Feng, J.; Xu, B. Wheat grain phenolics: A review on composition, bioactivity, and influencing factors. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 6167–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, M.P.; Braun, H.-J. Wheat Improvement; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; p. 629. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, O.P.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, A.; Khan, M.K.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, G.P. Wheat Science: Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Properties, Processing, Storage, Bioactivity, and Product Development; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, I.N.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Kumar, C.K.; Schmitt, H.; Gales, A.C.; Bertagnolio, S.; Sharland, M.; Laxminarayan, R. The scope of the antimicrobial resistance challenge. Lancet 2024, 403, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.K.; Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 80, 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Almotiri, A.; AlZeyadi, Z.A. Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Drivers—A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saadony, M.T.; Saad, A.M.; Mohammed, D.M.; Korma, S.A.; Alshahrani, M.Y.; Ahmed, A.E.; Ibrahim, E.H.; Salem, H.M.; Alkafaas, S.S.; Saif, A.M.; et al. Medicinal plants: Bioactive compounds, biological activities, combating multidrug-resistant microorganisms, and human health benefits—A comprehensive review. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1491777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jubair, N.; Rajagopal, M.; Chinnappan, S.; Abdullah, N.B.; Fatima, A.; Zarrelli, A. Review on the Antibacterial Mechanism of Plant-Derived Compounds against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria (MDR). Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 3663315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Hameed, A.; Tahir, M.F. Wheat quality: A review on chemical composition, nutritional attributes, grain anatomy, types, classification, and function of seed storage proteins in bread making quality. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1053196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Wheat—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1668/wheat/ (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Shewry, P.R.; Evers, A.D.; Bechtel, D.B.; Abecassis, J.; Khan, K.; Shewry, P. Development, structure, and mechanical properties of the wheat grain. In Wheat: Chemistry and Technology, 4th ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 51–96. [Google Scholar]

- Joye, I.J. Dietary fibre from whole grains and their benefits on metabolic health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, G.; De Maio, A.C.; Catalano, A.; Ceramella, J.; Iacopetta, D.; Bonofiglio, D.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S. Ancient Wheat as Promising Nutraceuticals for the Prevention of Chronic and Degenerative Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 30, 3384–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Sibakov, N.; Poutanen, K.; Micard, V. How does wheat grain, bran and aleurone structure impact their nutritional and technological properties? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 41, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficco, D.B.M.; Petroni, K.; Mistura, L.; D’Addezio, L. Polyphenols in Cereals: State of the Art of Available Information and Its Potential Use in Epidemiological Studies. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marone, D.; Mastrangelo, A.M.; Borrelli, G.M.; Mores, A.; Laidò, G.; Russo, M.A.; Ficco, D.B.M. Specialized metabolites: Physiological and biochemical role in stress resistance, strategies to improve their accumulation, and new applications in crop breeding and management. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 172, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieri, M.; Kumar, K.; Boutin, A. Antibiotic resistance. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Holley, R.A. Use of natural antimicrobials to increase antibiotic susceptibility of drug resistant bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 140, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Jia, W.; Guo, T.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. Natural antimicrobials from plants: Recent advances and future prospects. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024 Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/1a41ef7e-dd24-4ce6-a9a6-1573562e7f37/content (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Perlin, D.S.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: Prevalence, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e383–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisoschi, A.M.; Pop, A.; Georgescu, C.; Turcuş, V.; Olah, N.K.; Mathe, E. An overview of natural antimicrobials role in food. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshawih, S.; Abdullah Juperi, R.a.N.A.; Paneerselvam, G.S.; Ming, L.C.; Liew, K.B.; Goh, B.H.; Al-Worafi, Y.M.; Choo, C.-Y.; Thuraisingam, S.; Goh, H.P.; et al. General Health Benefits and Pharmacological Activities of Triticum aestivum L. Molecules 2022, 27, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poudel, R.; Bhatta, M. Review of Nutraceuticals and Functional Properties of Whole Wheat. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lan, W.; Xie, J. Natural phenolic compounds: Antimicrobial properties, antimicrobial mechanisms, and potential utilization in the preservation of aquatic products. Food Chem. 2024, 440, 138198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidova, S.; Galabov, A.S.; Satchanska, G. Antibacterial, Antifungal, Antiviral Activity, and Mechanisms of Action of Plant Polyphenols. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.; Gao, N.; Zang, Z.; Meng, X.; Lin, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, Y.; Jin, Z.; Li, B. Classification and antioxidant assays of polyphenols: A review. J. Future Foods 2024, 4, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernin, A.; Guillier, L.; Dubois-Brissonnet, F. Inhibitory activity of phenolic acids against Listeria monocytogenes: Deciphering the mechanisms of action using three different models. Food Microbiol. 2019, 80, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boz, H. p-Coumaric acid in cereals: Presence, antioxidant and antimicrobial effects. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 2323–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, C.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Martín-Álvarez, P.J.; Bills, G.; Vicente, M.F.; Basilio, A.; Rivas, C.L.; Requena, T.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Bartolomé, B. Antimicrobial activity of phenolic acids against commensal, probiotic and pathogenic bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 2010, 161, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Arnoot, S.; Abdullah, Q.Y.M.; Ail Al-Maqtari, M.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Abdulwahab Al-Shamahy, H.; Salah, E.M.M.; Al-Thobhani, A.; Al-Bana, M.N.Q.; Al-Akhali, B. Multitarget Antimicrobial Mechanisms of Plant Extracts: A Review of Harnessing Phytochemicals Against Drug-Resistant Pathogens. Sana’a Univ. J. Med. Health Sci. 2025, 19, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.-Y. Antioxidative and Antimicrobial Activities of Active Materials Derived from Triticum aestivum Sprouts. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2010, 53, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.; Wang, H.; Rao, S.; Sun, J.; Ma, C.; Li, J. p-Coumaric acid kills bacteria through dual damage mechanisms. Food Control 2012, 25, 550–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Szablewski, T.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Góral, T.; Kurasiak-Popowska, D.; Stuper-Szablewska, K. Assessment of Antimicrobial Properties of Phenolic Acid Extracts from Grain Infected with Fungi from the Genus Fusarium. Molecules 2022, 27, 1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchowilska, E.; Wiwart, M.; Grabowska, G. Antifungal activity of methanol extracts from spikes of Triticum spelta and Triticum aestivum genotypes differing in their response to Fusarium culmorum inoculation. Biologia 2008, 63, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, A.; Sarkar, D.; Shetty, K. Improving Phenolic-Linked Antioxidant, Antihyperglycemic and Antibacterial Properties of Emmer and Conventional Wheat Using Beneficial Lactic Acid Bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 1, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, G.; Guan, Y.; Yi, H.; Lai, S.; Sun, Y.; Cao, S. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of plant flavonoids to gram-positive bacteria predicted from their lipophilicities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grande, T.; Souid, A.; Ciardi, M.; Della Croce, C.M.; Frassinetti, S.; Bramanti, E.; Longo, V.; Pozzo, L. Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of whole flours obtained from different species of Triticum genus. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 1575–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-Y.; Kim, W.-G. Tyrosol blocks E. coli anaerobic biofilm formation via YbfA and FNR to increase antibiotic susceptibility. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Ramgopal, M.; Ramanjaneyulu, G.; Anuradha, C.M.; Suresh Kumar, C. Syringic acid (SA)—A Review of Its Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Pharmacological and Industrial Importance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, E.F.; Mansour, S.C.; Hancock, R.E.W. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Introduction. In Antimicrobial Peptides; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shagaghi, N.; Palombo, E.A.; Clayton, A.H.A.; Bhave, M. Antimicrobial peptides: Biochemical determinants of activity and biophysical techniques of elucidating their functionality. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhatwalia, V.K.; Sati, O.P.; Tripathi, M.K.; Kumar, A. Isolation, characterization and antimicrobial activity at diverse dilution of wheat puroindoline protein. World J. Agric. Sci. 2009, 5, 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.F. The antimicrobial properties of the puroindolines, a review. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capparelli, R.; Amoroso, M.G.; Palumbo, D.; Iannaccone, M.; Faleri, C.; Cresti, M. Two Plant Puroindolines Colocalize in Wheat Seed and in vitro Synergistically Fight Against Pathogens. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 58, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, V.; Kaur, K.; Singh, D.; Kumar, V.; Kaur, H.; Dhaliwal, H.S. Molecular characterization of diverse wheat germplasm for puroindolineproteins and their antimicrobial activity. Turk. J. Biol. 2015, 39, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, E.F.; Petersen, A.P.; Lau, C.K.; Jing, W.; Storey, D.G.; Vogel, H.J. Mechanism of action of puroindoline derived tryptophan-rich antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 1802–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, P.K.; Turner, K.L.; Crockett, T.M.; Lu, X.; Morris, C.F.; Konkel, M.E. Inhibitory Effect of Puroindoline Peptides on Campylobacter jejuni Growth and Biofilm Formation. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 702762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szpak, M.; Trziszka, T.; Polanowski, A.; Gburek, J.; Gołąb, K.; Juszczyńska, K.; Janik, P.; Malicki, A.; Szyplik, K. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Cystatin against Selected Strains of Escherichia coli. Folia Biol. 2014, 62, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Christova, P.K.; Christov, N.K.; Mladenov, P.V.; Imai, R. The wheat multidomain cystatin TaMDC1 displays antifungal, antibacterial, and insecticidal activities in planta. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hsouna, A.; Ben Saad, R.; Dhifi, W.; Mnif, W.; Brini, F. Novel non-specific lipid-transfer protein (TdLTP4) isolated from durum wheat: Antimicrobial activities and anti-inflammatory properties in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 154, 104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ma, K.; Ji, G.; Pan, L.; Zhou, Q. Lipid transfer proteins involved in plant–pathogen interactions and their molecular mechanisms. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1815–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talas-Oğraş, T. Screening antimicrobial activities of basic protein fractions from dry and germinated wheat seeds. Biol. Plant. 2004, 48, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.; Islam, Z.; Islam, S.; Hossain, S.; Islam, S.M. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) against four bacterial strains. SKUAST J. Res. 2018, 20, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Petrovici, A.-G.; Spennato, M.; Bîtcan, I.; Péter, F.; Cotarcă, L.; Todea, A.; Ordodi, V.L. A Comprehensive Review of Azelaic Acid Pharmacological Properties, Clinical Applications, and Innovative Topical Formulations. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaggiari, C.; Annunziato, G.; Spadini, C.; Montanaro, S.L.; Iannarelli, M.; Cabassi, C.S.; Costantino, G. Extraction and Quantification of Azelaic Acid from Different Wheat Samples (Triticum durum Desf.) and Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2023, 28, 2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H. Antimicrobial Activities of 1,4-Benzoquinones and Wheat Germ Extract. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlem, M.A., Jr.; Nguema Edzang, R.W.; Catto, A.L.; Raimundo, J.-M. Quinones as an Efficient Molecular Scaffold in the Antibacterial/Antifungal or Antitumoral Arsenal. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, H.R.; Copaja, S.V.; Lazo, W. Antimicrobial activity of natural 2-benzoxazolinones and related derivatives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 3255–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Ng, T.B. Demonstration of antifungal and anti-human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase activities of 6-methoxy-2-benzoxazolinone and antibacterial activity of the pineal indole 5-methoxyindole-3-acetic acid. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002, 132, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzai, K.; Isono, K.; Okuma, K.; Suzuki, S. The new antibiotics, questiomycins A and B. J. Antibiot. Ser. A 1990, 13, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo Vergara, H.; Lazo Araya, W. Antimicrobial Activity of Cereal Hydroxamic Acids and Related Compounds. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 569–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzani, C.; Vanara, F.; Bhandari, D.R.; Bruni, R.; Spengler, B.; Blandino, M.; Righetti, L. 5-n-Alkylresorcinol Profiles in Different Cultivars of Einkorn, Emmer, Spelt, Common Wheat, and Tritordeum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 14092–14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marentes-Culma, R.; Orduz-Díaz, L.L.; Coy-Barrera, E. Targeted Metabolite Profiling-Based Identification of Antifungal 5-n-Alkylresorcinols Occurring in Different Cereals against Fusarium oxysporum. Molecules 2019, 24, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabolotneva, A.A.; Shatova, O.P.; Sadova, A.A.; Shestopalov, A.V.; Roumiantsev, S.A.; Huerta, J.M. An Overview of Alkylresorcinols Biological Properties and Effects. J. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozubek, A.; Tyman, J.H.P. Resorcinolic Lipids, the Natural Non-isoprenoid Phenolic Amphiphiles and Their Biological Activity. Chem. Rev. 1998, 99, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A.; Mohdaly, A.A.A.; Elneairy, N.A.A. Wheat Germ: An Overview on Nutritional Value, Antioxidant Potential and Antibacterial Characteristics. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, 6, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, R.a.T.; Tuncer, E. Antimicrobial Activity of Wheat Germ Oil: A Disk Diffusion Study. Health Sci. Stud. J. 2024, 4, 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Z.; Purnawan, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Ismail, B.B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Guo, M. A novel antimicrobial peptide WBp-1 from wheat bran: Purification, characterization and antibacterial potential against Listeria monocytogenes. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, A.M.A.A.; Zidan, S.A.H.; Shehata, R.M.; El-Sheikh, H.H.; Ameen, F.; Stephenson, S.L.; Al-Bedak, O.A.-H.M. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and molecular docking of methyl ferulate and oleic acid produced by Aspergillus pseudodeflectus AUMC 15761 utilizing wheat bran. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedain-Ardabili, M.; Azizi, M.-H.; Salami, M. Evaluation of antioxidant, α-amylase-inhibitory and antimicrobial activities of wheat gluten hydrolysates produced by ficin protease. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 2892–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, S.A. Phytochemical and pharmacological screening of wheat grass Juice (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2011, 9, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Das, A.; Raychaudhuri, U.; Chakraborty, R. Antimicrobial effect of edible plant extract on the growth of some foodborne bacteria including pathogens. Nutrafoods 2012, 11, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.A.M.; Pradeep, M.; Laxmi, A. Quantitative Estimation of Chlorophyll and Carotene Content in Triticum aestivum Hexane Extract and Antimicrobial Effect against Salmonella. FPI 1 2016, 1, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan, A.; Selvi, A.; Manonmani, H.K. The Anti-Microbial Properties of Triticum aestivum (Wheat Grass). Int. J. Biotechnol. Wellness Ind. 2015, 4, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivanoğlu, H.; Gündüz, H.H.; Demirci, M. An Investigation of Antimicrobial Activity of Wheat Grass Juice, Barley Grass Juice, Hardaliye and Boza. Int. Interdiscip. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scarcelli, E.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Bonofiglio, D.; Catalano, A.; Basile, G.; Aiello, F.; Sinicropi, M.S. Wheat as a Storehouse of Natural Antimicrobial Compounds. Molecules 2025, 30, 4774. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244774

Scarcelli E, Iacopetta D, Ceramella J, Bonofiglio D, Catalano A, Basile G, Aiello F, Sinicropi MS. Wheat as a Storehouse of Natural Antimicrobial Compounds. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4774. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244774

Chicago/Turabian StyleScarcelli, Eva, Domenico Iacopetta, Jessica Ceramella, Daniela Bonofiglio, Alessia Catalano, Giovanna Basile, Francesca Aiello, and Maria Stefania Sinicropi. 2025. "Wheat as a Storehouse of Natural Antimicrobial Compounds" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4774. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244774

APA StyleScarcelli, E., Iacopetta, D., Ceramella, J., Bonofiglio, D., Catalano, A., Basile, G., Aiello, F., & Sinicropi, M. S. (2025). Wheat as a Storehouse of Natural Antimicrobial Compounds. Molecules, 30(24), 4774. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244774