Design and Biological Evaluation of Monoterpene-Conjugated (S)-2-Ethoxy-3-(4-(4-hydroxyphenethoxy)phenyl)propanoic Acids as New Dual PPARα/γ Agonists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. In Vitro Biological Testing

2.2.1. MTT Assay

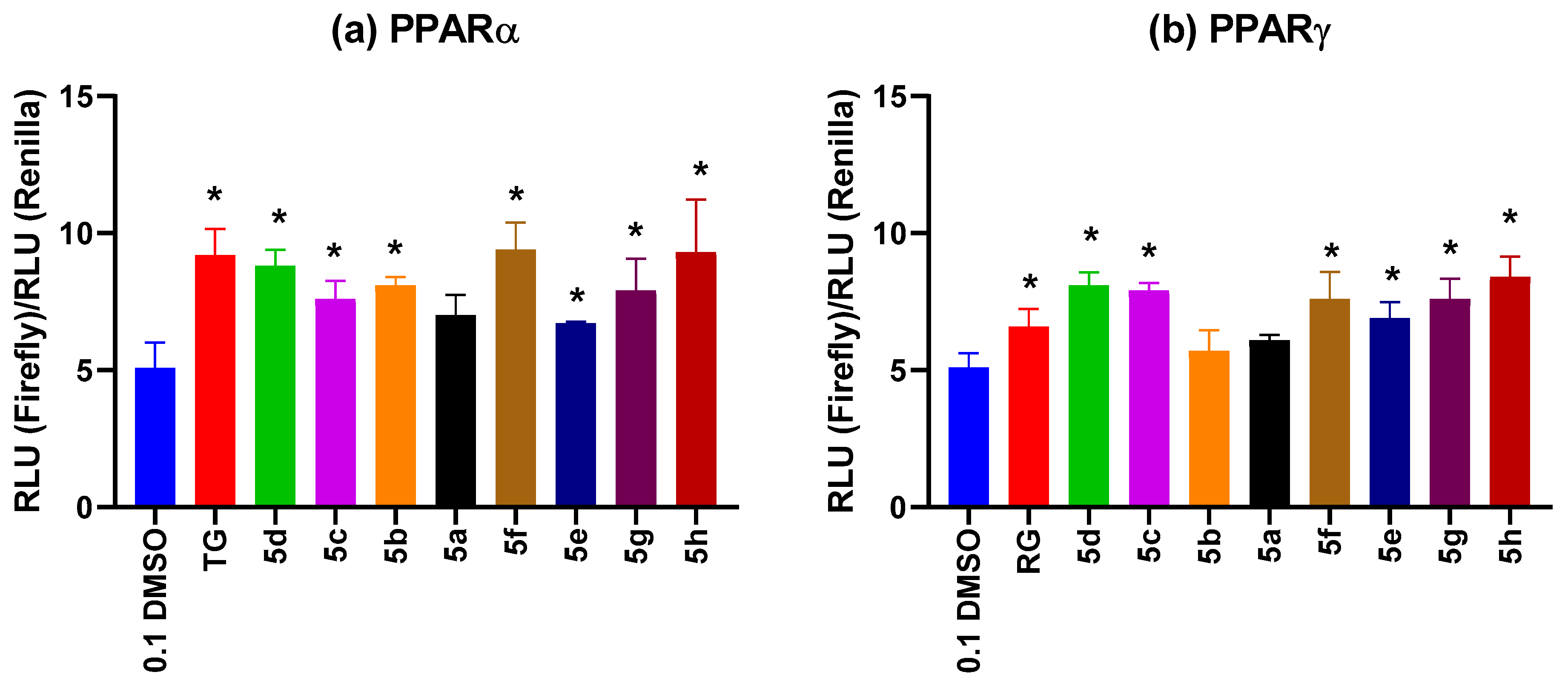

2.2.2. PPARα and PPARγ Receptor Agonist Activity Evaluation

2.3. In Vivo Experiments

2.3.1. Body Mass Dynamics

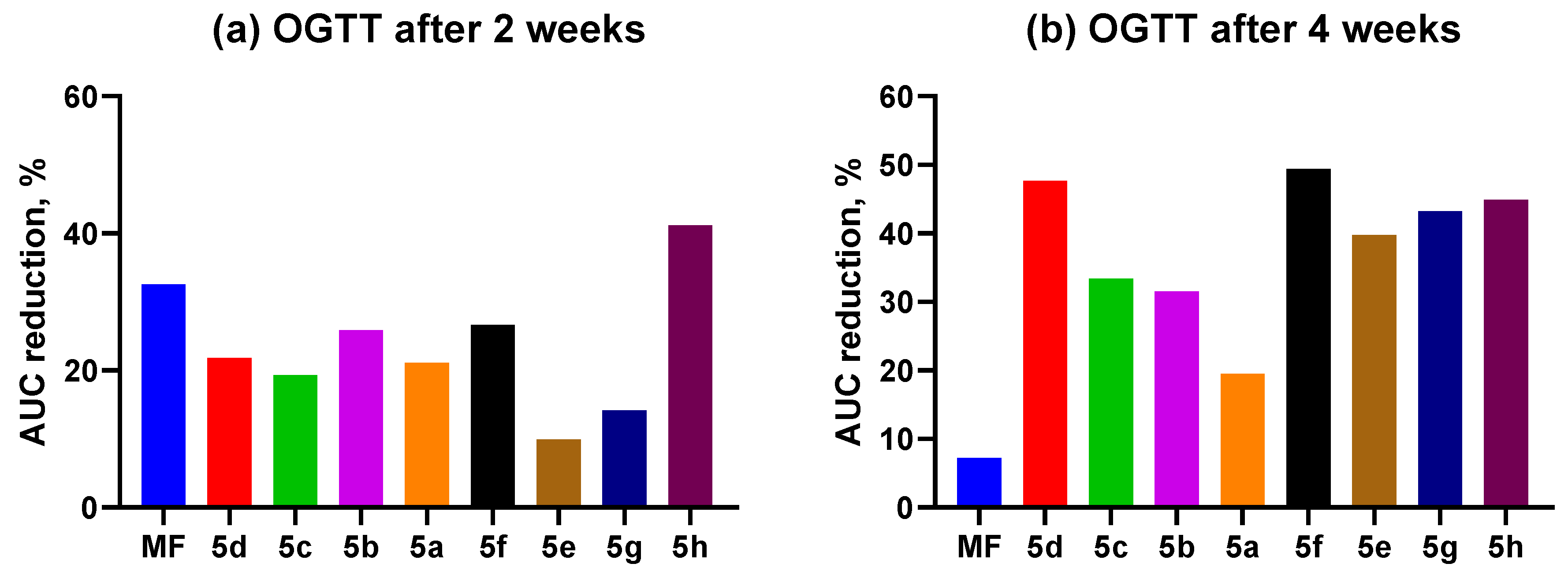

2.3.2. OGTT

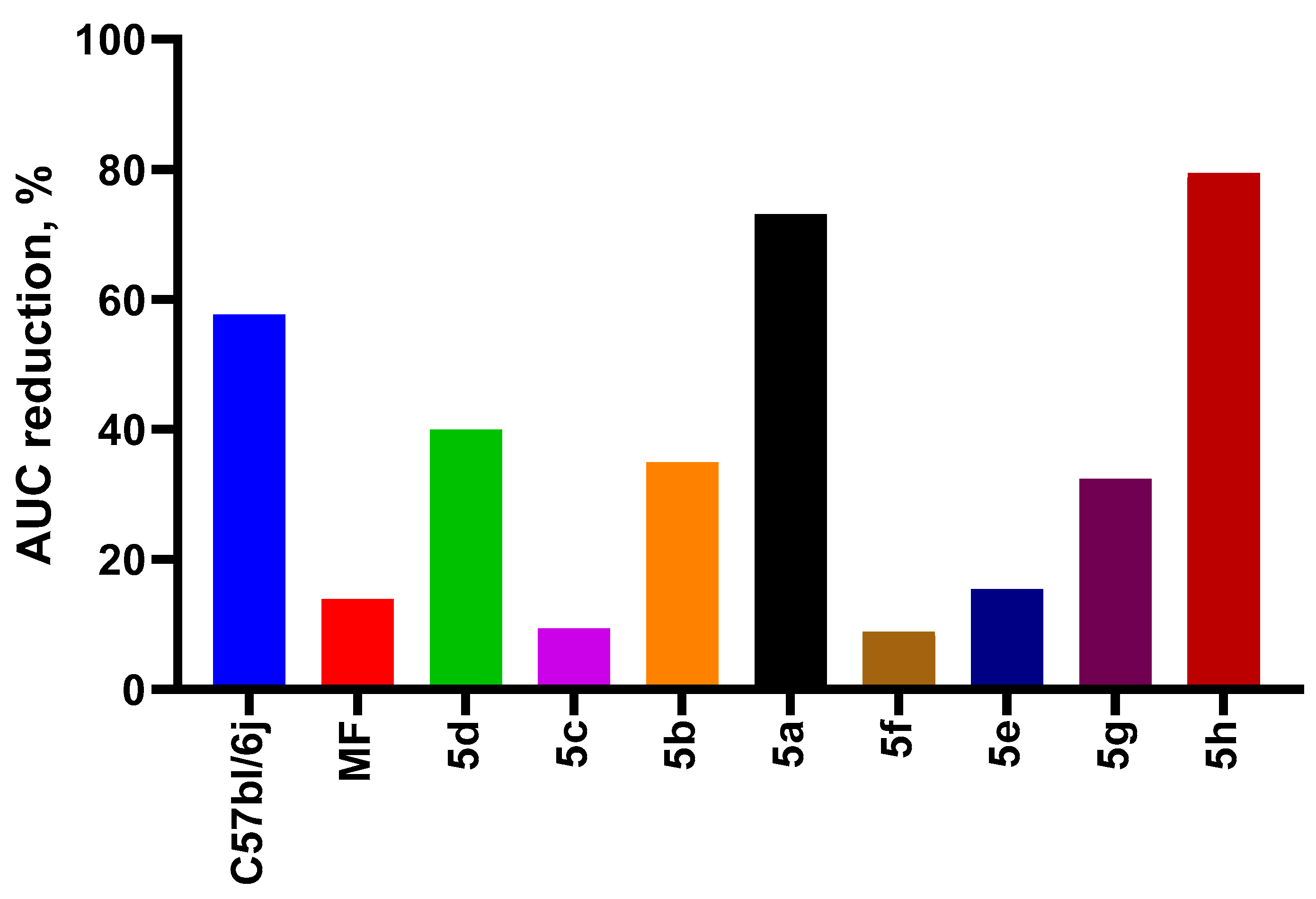

2.3.3. ITT

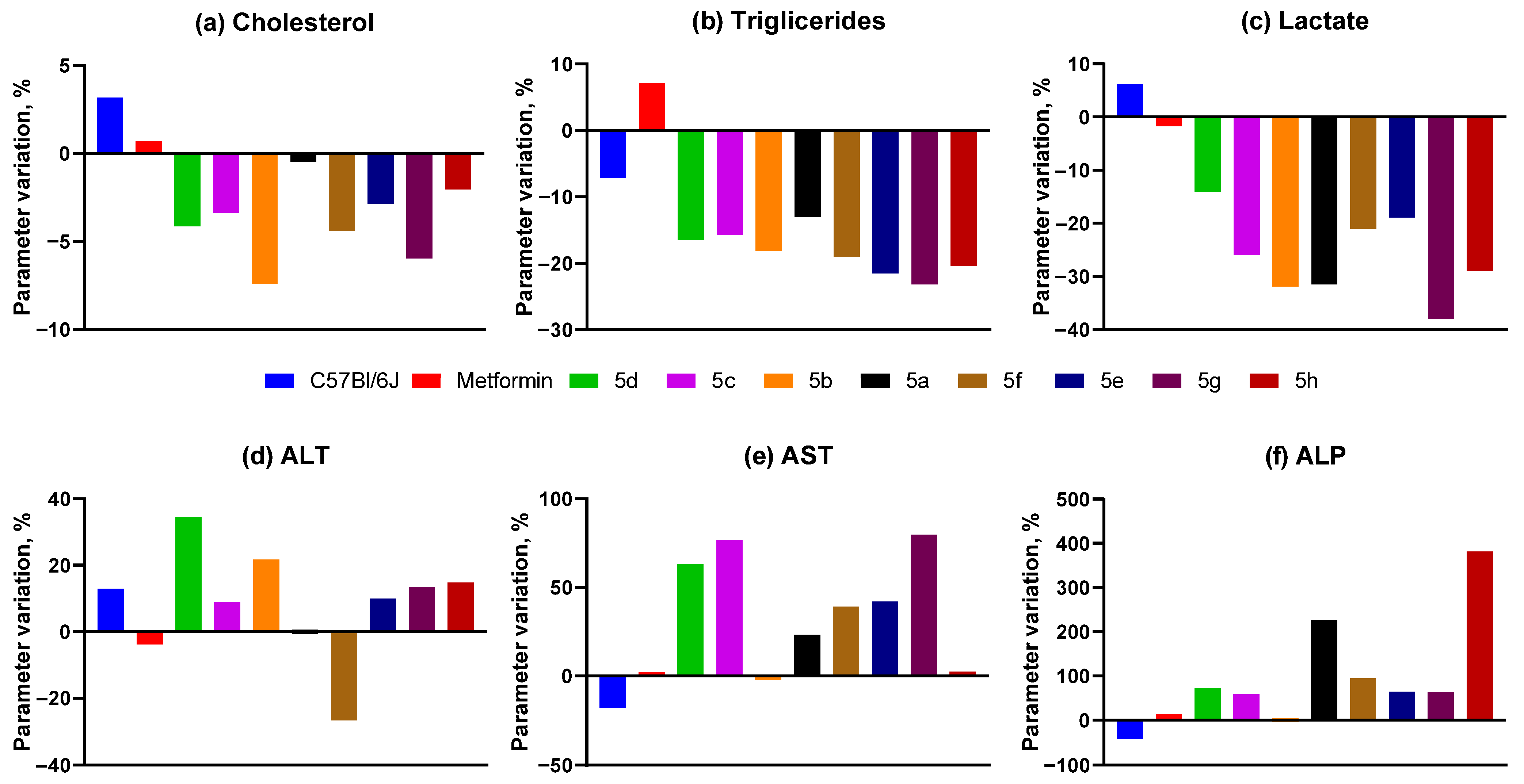

2.3.4. Biochemical Analysis

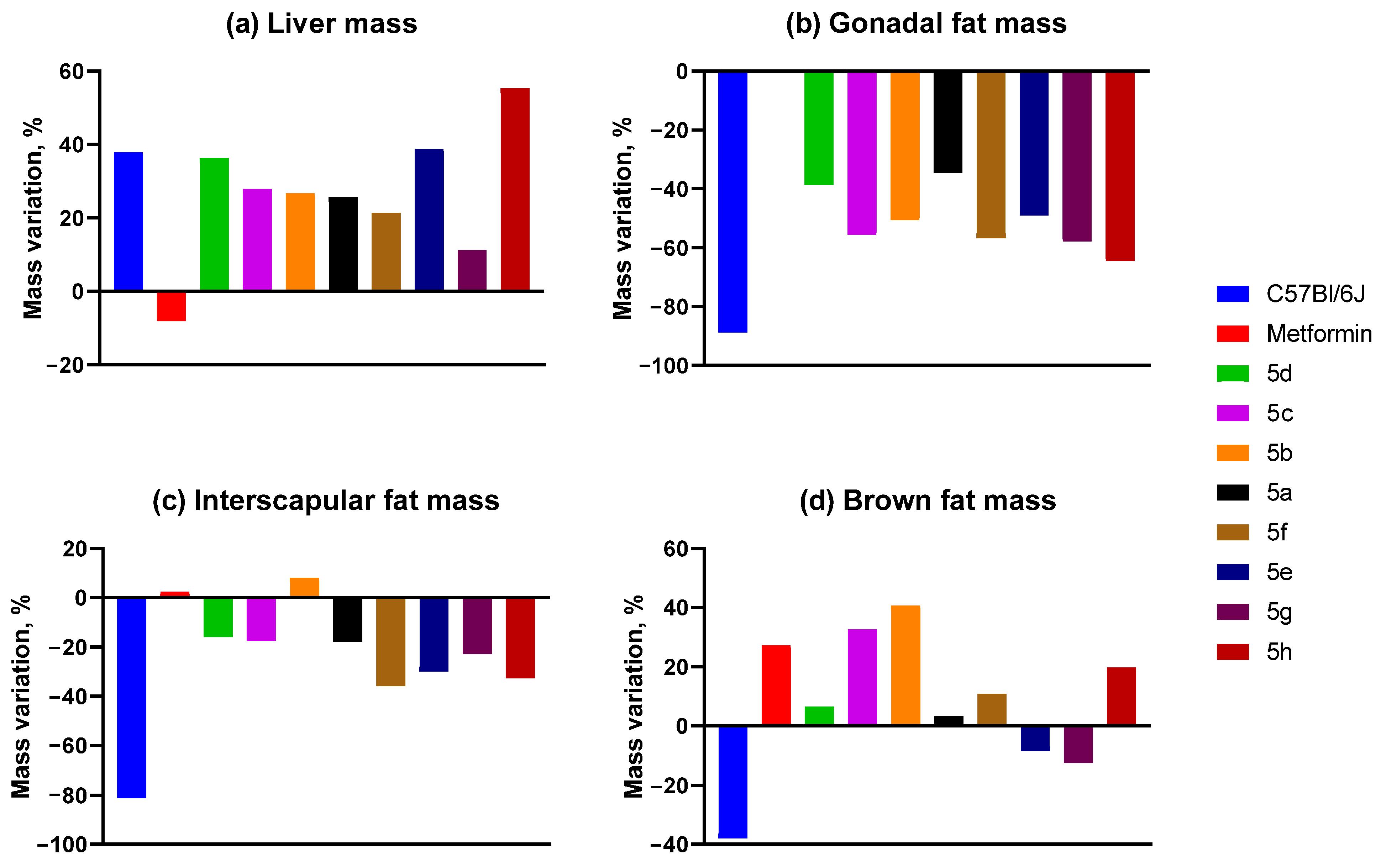

2.3.5. Mass of Animal Organs and Tissues

2.3.6. Histology

3. Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. Biology

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.2. In Vitro Biological Testing

4.2.1. MTT Assay

4.2.2. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay to Study the Compounds’ Activity and Specificity

4.3. In Vivo Experiments

4.3.1. Animals

4.3.2. The OGTT

4.3.3. The ITT

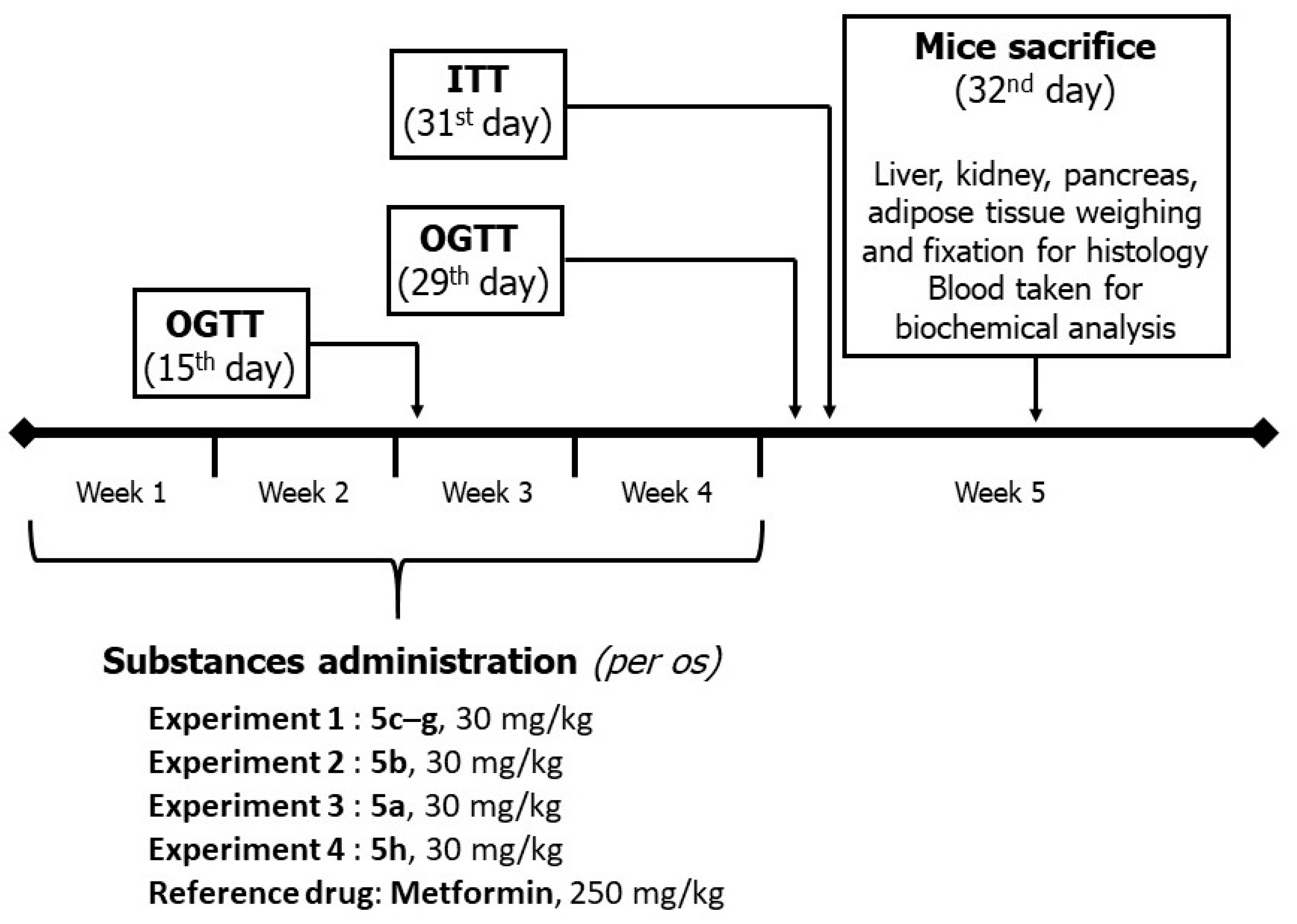

4.3.4. The AY Mice Experiment Design

4.3.5. Biochemical Assays

4.3.6. Histological Examination

4.3.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors |

| DIAD | Diisopropyl Azodicarboxylate |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OGTT | Oral Glucose Tolerance Test |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ITT | Insulin Tolerance Test |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

References

- Neeland, I.J.; Lim, S.; Tchernof, A.; Gastaldelli, A.; Rangaswami, J.; Ndumele, C.E.; Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Després, J.P. Metabolic syndrome. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christofides, A.; Konstantinidou, E.; Jani, C.; Boussiotis, V.A. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) in immune responses. Metabolism 2021, 114, 154338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Pellegrino, M.; Carluccio, M.A.; Calabriso, N.; Wabitsch, M.; Storelli, C.; Wright, M.; De Caterina, R. Therapeutic potential of the dual peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)α/γ agonist aleglitazar in attenuating TNF-α-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in human adipocytes. Pharmacol. Res. 2016, 107, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakes, N.D.; Thalén, P.; Hultstrand, T.; Jacinto, S.; Camejo, G.; Wallin, B.; Ljung, B. Tesaglitazar, a dual PPARα/γ agonist, ameliorates glucose and lipid intolerance in obese Zucker rats. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 289, R938–R946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, B.J.; Rosenstock, J.; Anzalone, D.; Tou, C.; Ohman, K.P. Effect of tesaglitazar, a dual PPAR alpha/gamma agonist, on glucose and lipid abnormalities in patients with type 2 diabetes: A 12-week dose-ranging trial. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006, 22, 2575–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K.; Topol, E.J. Effect of Muraglitazar on Death and Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA 2005, 294, 2581–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiewicz, M.B.; Thorup, I.; Nielsen, H.S.; Andersen, H.V.; Hegelund, A.C.; Iversen, L.; Guldberg, T.S.; Brinck, P.R.; Sjogren, I.; Thinggaard, U.K.; et al. Generalized cellular hypertrophy is induced by a dual-acting PPAR agonist in rat urinary bladder urothelium in vivo. Toxicol. Pathol. 2005, 33, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Pharmacodynamic/Pharmacokinetic Study of Aleglitazar in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus on Treatment with Lisinopril [Clinical Trial Protocol]. ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT01398267. 2011. Available online: https://ctv.veeva.com/study/a-pharmacodynamic-pharmacokinetic-study-of-aleglitazar-in-patients-with-type-2-diabetes-mellitus-on (accessed on 19 July 2011).

- Agrawal, R. The first approved agent in the Glitazar’s Class: Saroglitazar. Curr. Drug Targets 2014, 15, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.P.; Shan, S.; Chen, Y.T.; Ning, Z.Q.; Sun, S.J.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, X.Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D.H. The PPARα/γ dual agonist chiglitazar improves insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in MSG obese rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.R.; Giri, S.R.; Bhoi, B.; Trivedi, C.; Rath, A.; Rathod, R.; Ranvir, R.; Kadam, S.S.; Patel, H.; Swami, P.; et al. Saroglitazar, a novel PPARα/γ agonist with predominant PPARα activity, shows lipid-lowering and insulin-sensitizing effects in preclinical models. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2015, 3, e00136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalik, L.; Auwerx, J.; Berger, J.P.; Chatterjee, V.K.; Glass, C.K.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Grimaldi, P.A.; Kadowaki, T.; Lazar, M.A.; O’Rahilly, S.; et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LXI. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomenko, V.; Blokhin, M.; Kuranov, S.; Khvostov, M.; Baev, D.; Borisova, M.S.; Luzina, O.; Tolstikova, T.G.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Triterpenic Acid Amides as a Promising Agent for Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome. Sci. Pharm. 2021, 89, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhin, M.E.; Kuranov, S.O.; Khvostov, M.V.; Fomenko, V.V.; Luzina, O.A.; Zhukova, N.A.; Elhajjar, C.; Tolstikova, T.G.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Terpene-Containing Analogues of Glitazars as Potential Therapeutic Agents for Metabolic Syndrome. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 2230–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khvostov, M.V.; Blokhin, M.E.; Borisov, S.A.; Fomenko, V.V.; Meshkova, Y.V.; Zhukova, N.A.; Nikonova, S.V.; Pavlova, S.V.; Pogosova, M.A.; Medvedev, S.P.; et al. Antidiabetic Effect of Dihydrobetulonic Acid Derivatives as Pparα/γ Agonists. Sci. Pharm. 2024, 92, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, L.D.R.; Viana, N.R.; Coêlho, A.G.; Barbosa, C.O.; Barros, D.S.L.; Martins, M.D.C.C.E.; Ramos, R.M.; Arcanjo, D.D.R. Use of Monoterpenes as Potential Therapeutics in Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Review. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 2023, 1512974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doskina, E.V.; Maganova, F.I.; Zotova, E.M. The role of natural terpenoids in early prevention of atherosclerosis and metabolic syndrome. Diary Kazan Med. Sch. 2019, 2, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Lacerus, L.A.; Pinigin, A.F.; Pinigina, N.M.; Maganova, F.I.; Makarov, V.G. Terpenoid Agent for the Prevention and Treatment of Atherosclerosis and Correction of Metabolic Syndrome. WO Patent No. WO 2013/176564 A1, 21 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Murali, R.; Saravanan, R. Antidiabetic effect of d-limonene, a monoterpene in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biomed. Prev. Nutr. 2012, 2, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babukumar, S.; Vinothkumar, V.; Sankaranarayanan, C.; Srinivasan, S. Geraniol, a natural monoterpene, ameliorates hyperglycemia by attenuating the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1442–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, T.; Elanchezhiyan, C.; Insha, N.; Marimuthu, S. Effect of Perillyl Alcohol (POH) A Monoterpene on Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Status in High Fat Diet-Low Dose STZ Induced Type 2 Diabetes in Experimental Rats. Pharmacogn. J. 2019, 11, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Antidiabetic Potential of Monoterpenes: A Case of Small Molecules Punching above Their Weight. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.W.; Yu, R.; Yun, J.W. Monoterpene phenolic compound thymol promotes browning of 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 2329–2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohray, B.B.; Lohray, V.B.; Barot, V.K.; Raval, S.K.; Raval, P.S.; Basu, S. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Agonists, Their Preparation and Use. WO Patent WO 2003/009841 A1, 6 February 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baev, D.S.; Blokhin, M.E.; Chirkova, V.Y.; Belenkaya, S.V.; Luzina, O.A.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F.; Shcherbakov, D.N. Triterpenic Acid Amides as Potential Inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease. Molecules 2022, 28, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, S.L. Tesaglitazar: A promising approach in type 2 diabetes. Drugs Today 2006, 42, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng-Lai, A.; Levine, A. Rosiglitazone: An agent from the thiazolidinedione class for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Heart Dis. 2000, 2, 326–333. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.K.; Zhuang, Y.; Wahli, W. Synthetic and natural Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) agonists as candidates for the therapy of the metabolic syndrome. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2017, 21, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Vasudeva, N.; Sharma, S. Acute and chronic animal models for the evaluation of anti-diabetic agents. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2012, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.S.; Tan, W.R.; Low, Z.S.; Marvalim, C.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Tan, N.S. Exploration and Development of PPAR Modulators in Health and Disease: An Update of Clinical Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Viollet, B. Metformin: Update on mechanisms of action and repurposing potential. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 460–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhane, F.; Fite, A.; Daboul, N.; Al-Janabi, W.; Msallaty, Z.; Caruso, M.; Lewis, M.K.; Yi, Z.; Diamond, M.P.; Abou-Samra, A.B.; et al. Plasma Lactate Levels Increase during Hyperinsulinemic Euglycemic Clamp and Oral Glucose Tolerance Test. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Sugai, S. Specificity of transaminase activities in the prediction of drug-induced hepatotoxicity. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddick, J.A.; Bunger, W.B.; Sakano, T.K. Organic Solvents: Physical Properties and Methods of Purification, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann, T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 1983, 65, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, M.M. A mathematical model for the determination of total area under glucose tolerance and other metabolic curves. Diabetes Care 1994, 17, 152–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.C.; Ye, W.R.; Zheng, Y.J.; Zhang, S.S. Oxamate enhances the anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin in diabetic mice. Pharmacology 2017, 100, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell Viability, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group | 1 µM | 10 µM | 100 µM |

| 5c | 112.6 ± 7.2 | 6.0 ± 1.3 | 2.9 ± 0.8 |

| 5b | 110.8 ± 6.4 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.6 |

| 5f | 106.0 ± 14.1 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 |

| 5g | 113.1 ± 19.5 | 115.2 ± 20.4 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| 5h | 115.8 ± 4.8 | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borisov, S.A.; Blokhin, M.E.; Meshkova, Y.V.; Marenina, M.K.; Zhukova, N.A.; Pavlova, S.V.; Lastovka, A.V.; Fomenko, V.V.; Zhurakovsky, I.P.; Luzina, O.A.; et al. Design and Biological Evaluation of Monoterpene-Conjugated (S)-2-Ethoxy-3-(4-(4-hydroxyphenethoxy)phenyl)propanoic Acids as New Dual PPARα/γ Agonists. Molecules 2025, 30, 4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244775

Borisov SA, Blokhin ME, Meshkova YV, Marenina MK, Zhukova NA, Pavlova SV, Lastovka AV, Fomenko VV, Zhurakovsky IP, Luzina OA, et al. Design and Biological Evaluation of Monoterpene-Conjugated (S)-2-Ethoxy-3-(4-(4-hydroxyphenethoxy)phenyl)propanoic Acids as New Dual PPARα/γ Agonists. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244775

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorisov, Sergey A., Mikhail E. Blokhin, Yulia V. Meshkova, Maria K. Marenina, Nataliya A. Zhukova, Sophia V. Pavlova, Anastasiya V. Lastovka, Vladislav V. Fomenko, Igor P. Zhurakovsky, Olga A. Luzina, and et al. 2025. "Design and Biological Evaluation of Monoterpene-Conjugated (S)-2-Ethoxy-3-(4-(4-hydroxyphenethoxy)phenyl)propanoic Acids as New Dual PPARα/γ Agonists" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244775

APA StyleBorisov, S. A., Blokhin, M. E., Meshkova, Y. V., Marenina, M. K., Zhukova, N. A., Pavlova, S. V., Lastovka, A. V., Fomenko, V. V., Zhurakovsky, I. P., Luzina, O. A., Khvostov, M. V., Kudlay, D. A., & Salakhutdinov, N. F. (2025). Design and Biological Evaluation of Monoterpene-Conjugated (S)-2-Ethoxy-3-(4-(4-hydroxyphenethoxy)phenyl)propanoic Acids as New Dual PPARα/γ Agonists. Molecules, 30(24), 4775. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244775