Stability and Selectivity of Indocyanine Green Towards Photodynamic Therapy of CRL-2314 Breast Cancer Cells with Minimal Toxicity to HTB-125 Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Indocyanine Green

1.2. Pharmacokinetics of ICG

1.3. ICG-Mediated PDT

1.4. ICG Nanocarriers

2. Results

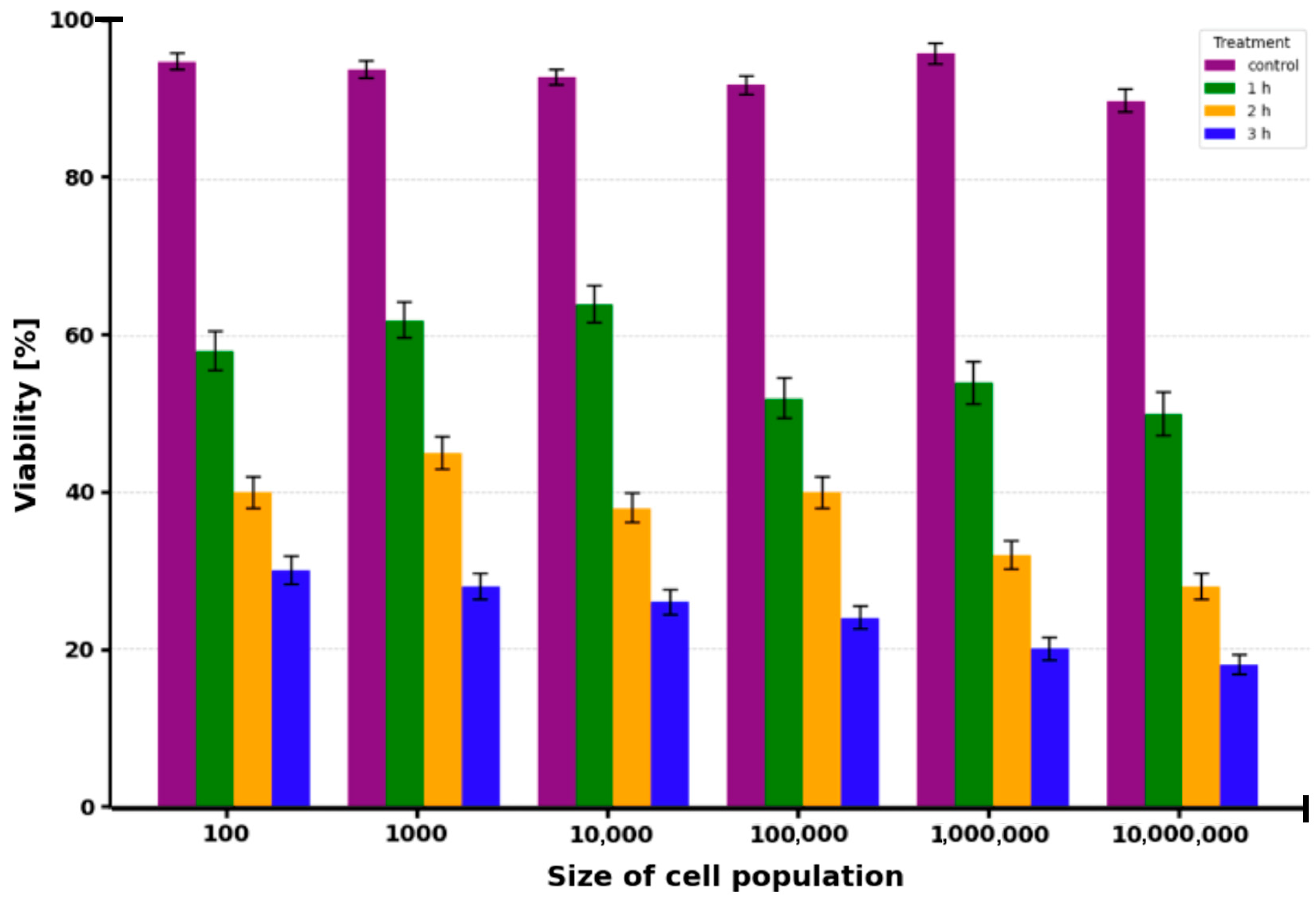

2.1. Cell Viability

2.2. Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) of Indocyanine Green Compound

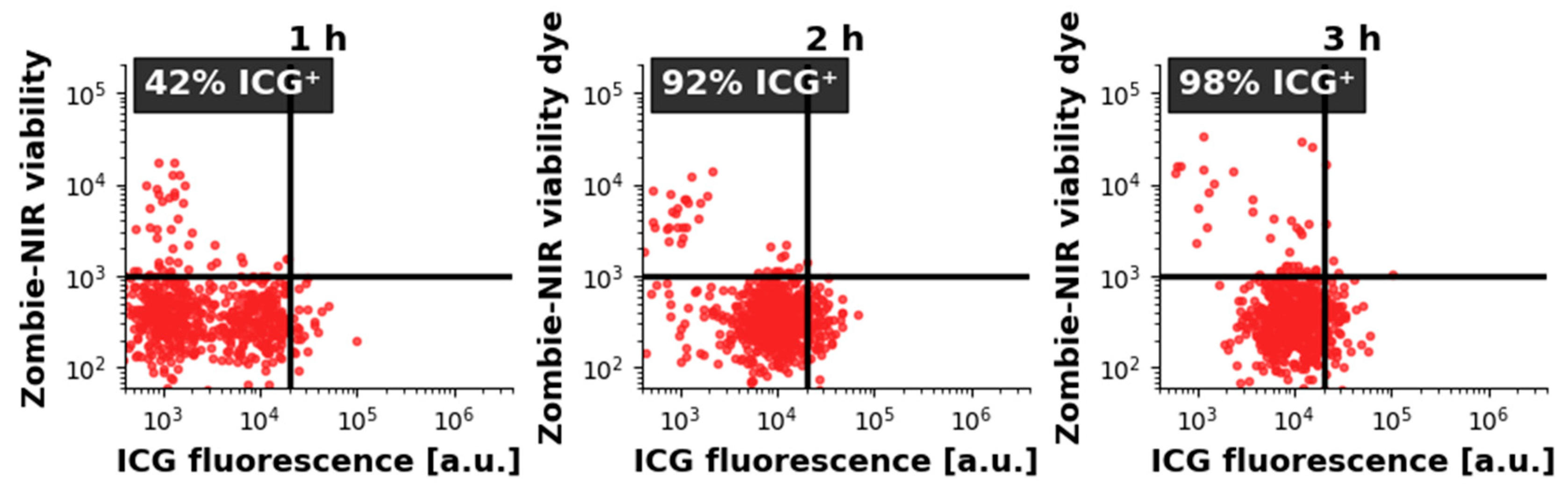

2.3. ICG Uptake by CRL-2314 Cells

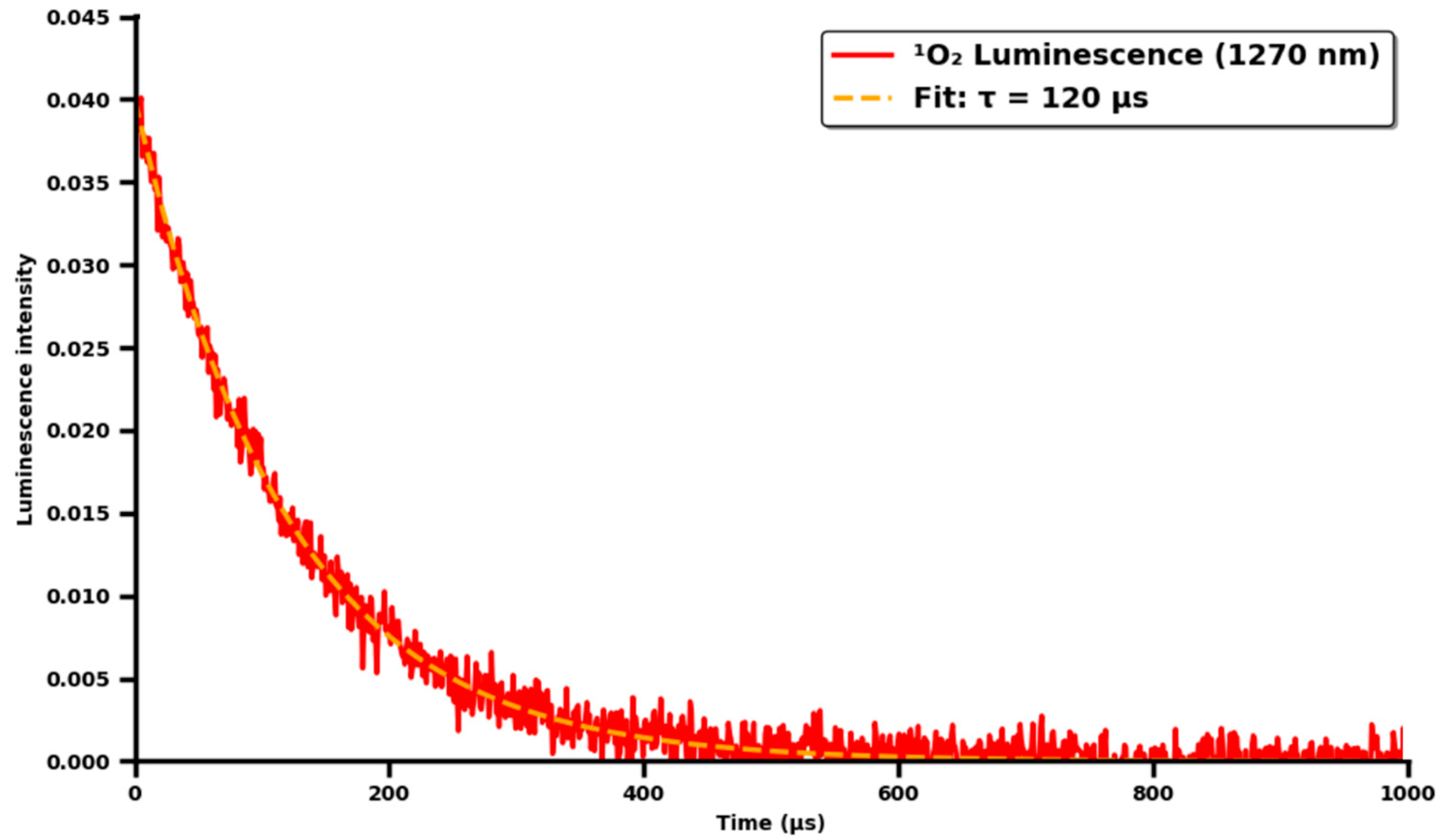

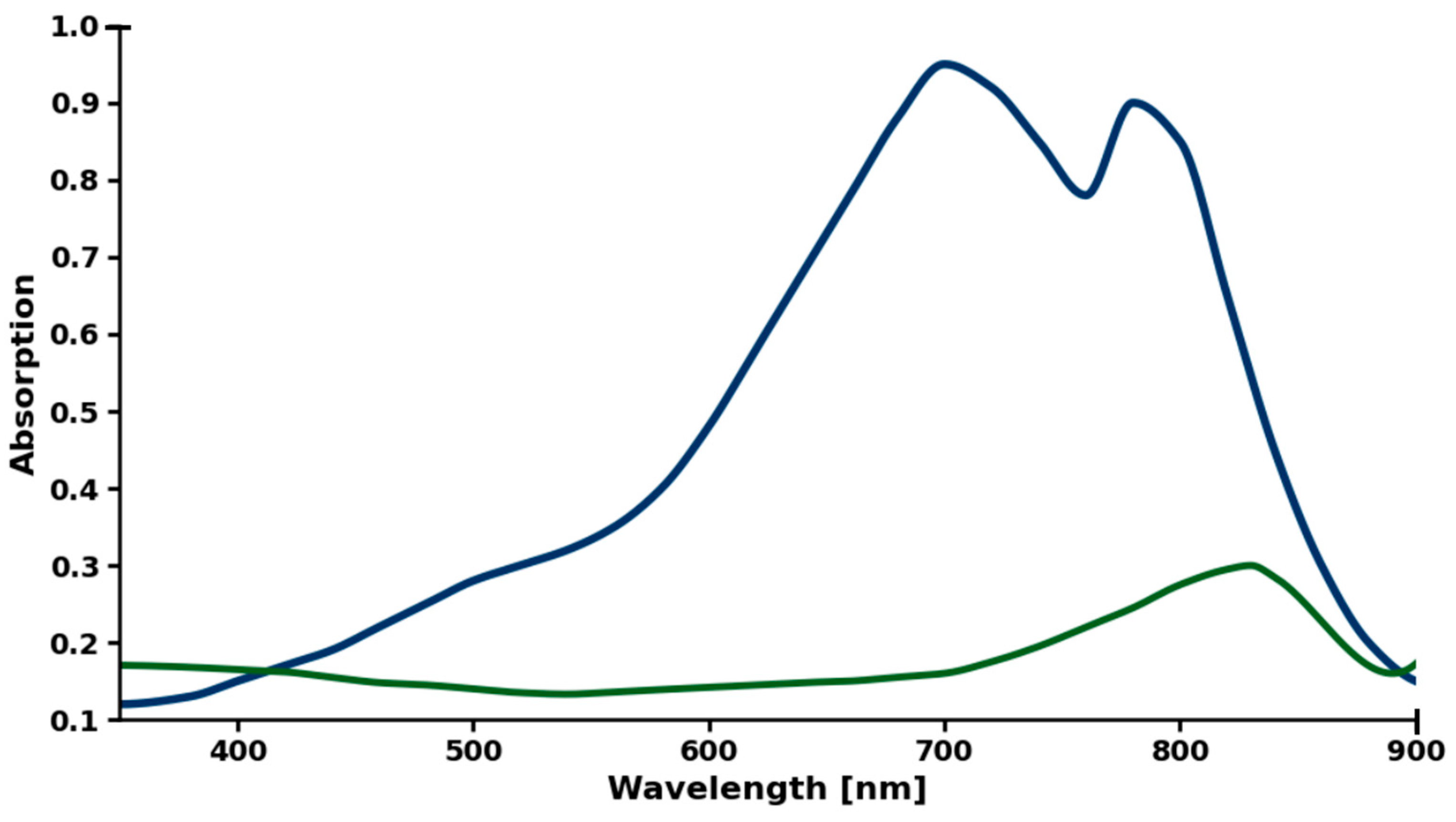

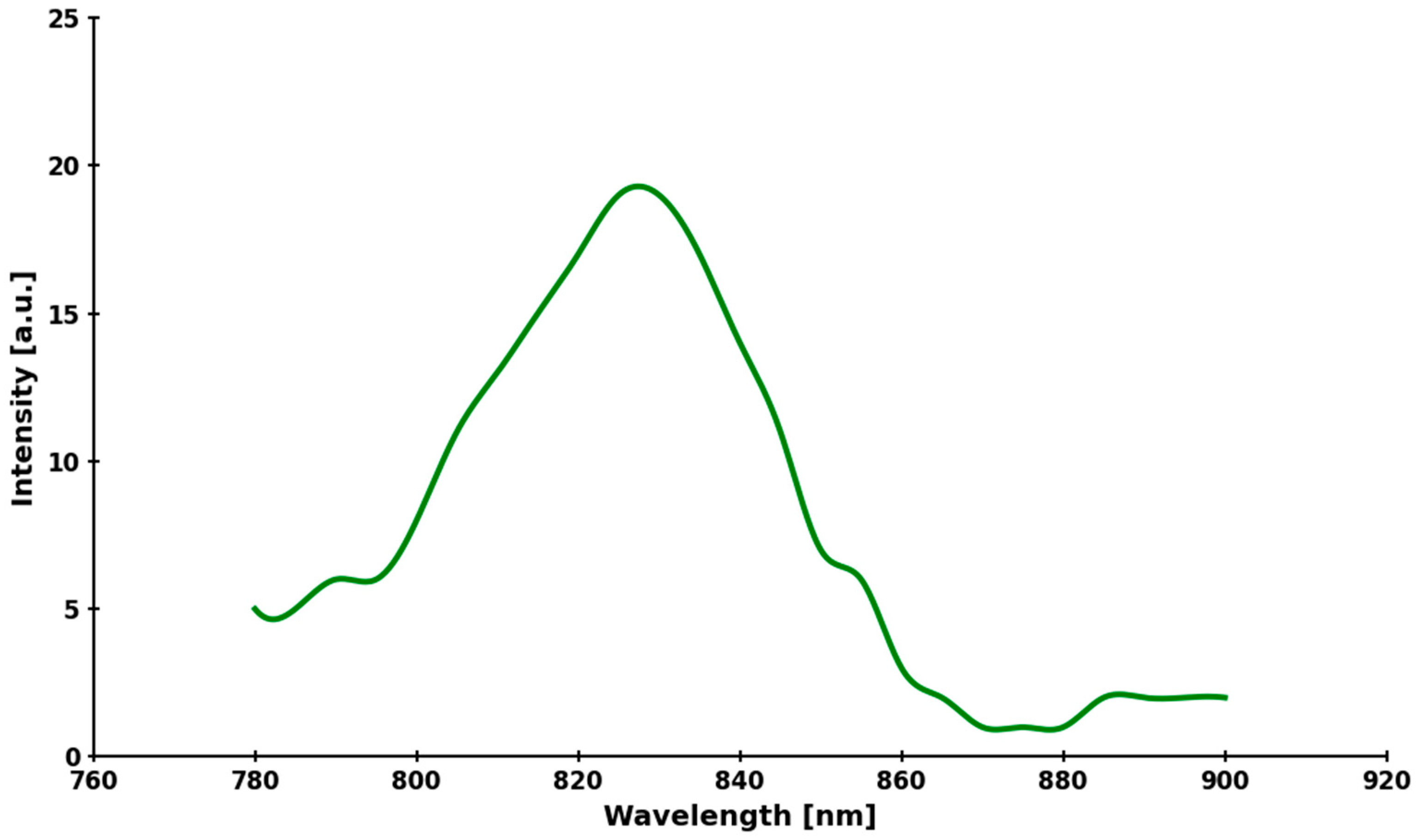

2.4. Assay of ICG Stability

3. Discussion

3.1. Chemical Stability of ICG

3.2. ICG Kinetics

3.3. Therapeutic Effect of ICG

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell-Line Culture

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Cell Counting and Viability Testing

4.4. IC50 Measurements Using ICG

4.5. Therapy Protocol

4.6. Lifetime Measurements

4.7. Stern–Volmer Quenching of Singlet Oxygen by DABCO

4.8. Spectroscopy Analysis

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1O2 | Singlet oxygen |

| 3O2 | Ground-state triplet oxygen |

| •OH | Hydroxyl radical |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| CME | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| DABCO | 1,4-Diazabicyclo [2.2.2]octane |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EGF | Epidermal growth factor |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| H2O | Water |

| ICD | Immunogenic cell death |

| ICG | Indocyanine green |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| O2−• | Superoxide radical |

| OATP | Organic anion-transporting polypeptide |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| RME | Receptor-mediated endocytosis |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| S0 | Ground singlet state |

| S1 | Excited singlet state |

| T1 | Triplet state |

| Φ_Δ | Singlet oxygen quantum yield |

| Φ_F | Fluorescence quantum yield |

| Φ_T | Triplet quantum yield |

References

- Aebisher, D.; Serafin, I.; Batóg-Szczęch, K.; Dynarowicz, K.; Chodurek, E.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D. Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Cancer—The Selection of Synthetic Photosensitizers. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przygoda, M.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Dynarowicz, K.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Aebisher, D. Cellular Mechanisms of Singlet Oxygen in Photodynamic Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerssens, D.; Cadoni, E.; Tack, L.; Madder, A. A Photosensitized Singlet Oxygen (1O2) Toolbox for Bio-Organic Applications: Tailoring 1O2 Generation for DNA and Protein Labelling, Targeting and Biosensing. Molecules 2022, 27, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharjan, P.S.; Bhattarai, H.K. Singlet Oxygen, Photodynamic Therapy, and Mechanisms of Cancer Cell Death. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 7211485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmut, Z.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, F.; Shi, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tang, Z.; Dong, B.; Gao, D.; et al. Medical Applications and Advancement of Near Infrared Photosensitive Indocyanine Green Molecules. Molecules 2023, 28, 6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindt, S.; Karampinis, I.; John, M.; Neumaier, M.; Nowak, K. Stability and degradation of indocyanine green in plasma, aqueous solution and whole blood. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntziachristos, V.; Bremer, C.; Weissleder, R. Fluorescence imaging with near-infrared light: New technological advances that enable in vivo molecular imaging. Eur. Radiol. 2003, 13, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Q. Advanced Near-Infrared Light for Monitoring and Modulating the Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Cell Functions in Living Systems. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1903783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldari, L.; Boni, L.; Cassinotti, E. Lymph node mapping with ICG near-infrared fluorescence imaging: Technique and results. Minim. Invasive Ther. Allied Technol. 2023, 32, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacz, P.; Pelc, Z.; Mlak, R.; Sędłak, K.; Kobiałka, S.; Mielniczek, K.; Leśniewska, M.; Chawrylak, K.; Polkowski, W.; Rawicz-Pruszyński, K.; et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: The role of ICG fluorescence after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2025, 210, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpunar, M.; Aebisher, D.; Cieniek, B.; Stefaniuk, I.; Dubiel, Ł.; Wal, A. Evidence for singlet oxygen production from indocyanine green by electron paramagnetic resonance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2025, 1869, 130861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Tovar, J.S.; Kassab, G.; Inada, N.M.; Bagnato, V.S.; Kurachi, C. Photobleaching Kinetics and Effect of Solvent in the Photophysical Properties of Indocyanine Green for Photodynamic Therapy. Chemphyschem 2023, 24, e202300381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.; Sadoqi, M.; Shao, J. Degradation kinetics of indocyanine green in aqueous solution. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 2090–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clutter, E.D.; Chen, L.L.; Wang, R.R. Role of photobleaching process of indocyanine green for killing neuroblastoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 589, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, N.; Jasinevicius, G.O.; Kassab, G.; Ding, L.; Bu, J.; Martinelli, L.P.; Ferreira, V.G.; Dhaliwal, A.; Chan, H.H.L.; Mo, Y.; et al. Nanostructure-Driven Indocyanine Green Dimerization Generates Ultra-Stable Phototheranostics Nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2023, 62, e202305564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dysart, J.S.; Patterson, M.S. Characterization of Photofrin photobleaching for singlet oxygen dose estimation during photodynamic therapy of MLL cells in vitro. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 2597–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.P.; Wang, T.D. Targeted Optical Imaging Agents in Cancer: Focus on Clinical Applications. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2018, 2018, 2015237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, O.H.; Kim, K.; Kim, C.G.; Choi, B.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.M.; Kim, H.K. Novel locally nebulized indocyanine green for simultaneous identification of tumor margin and intersegmental plane. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 4708–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, J.; Liu, A.; Hassan, S.; Gibson, A. Mechanisms of delayed indocyanine green fluorescence and applications to clinical disease processes. Surgery 2024, 176, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.R.; Liu, H.M.; Lu, C.W.; Shen, W.H.; Lin, I.J.; Liao, L.W.; Huang, Y.Y.; Shieh, M.J.; Hsiao, J.K. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B3 as a dual reporter gene for fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1705–1715, Erratum in FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8688–8689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cheng, D.; He, L.; Yuan, L. Recent Progresses in NIR-I/II Fluorescence Imaging for Surgical Navigation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 768698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isil, T.; Ozlem, K.; Defne, B.H.; Eray, G.M.; Abdurrahim, K. Toxicity evaluation of indocyanine green mediated photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Huang, M.; Zeng, S.; Zheng, J.; Peng, S.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.; Li, S. Innovative strategies for photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumor. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Ogawa, M.; Alford, R.; Choyke, P.L.; Urano, Y. New strategies for fluorescent probe design in medical diagnostic imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2620–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zou, J.; Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. DAMPs in the immunogenicity of cell death. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 3874–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, C.L.; Wang, L.; Barroso, M.; Corr, D.T. Non-Destructive Evaluation of Regional Cell Density Within Tumor Aggregates Following Drug Treatment. J. Vis. Exp. 2022, e64030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Lee, M.K.; Lim, S.J. Enhanced Stability of Indocyanine Green by Encapsulation in Zein-Phosphatidylcholine Hybrid Nanoparticles for Use in the Phototherapy of Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, D.; Sorrenti, M.; Catenacci, L.; Minzioni, P.; Marrubini, G.; Amendola, V.; Maestri, M.; Giunchedi, P.; Bonferoni, M.C. Association of Indocyanine Green with Chitosan Oleate Coated PLGA Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, C.D.; Cao, H.; Lakowicz, J.R. Enhanced photostability of ICG in close proximity to gold colloids. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2003, 59, 2611–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ara, E.S.; Noghreiyan, A.V.; Sazgarnia, A. Evaluation of photodynamic effect of Indocyanine green (ICG) on the colon and glioblastoma cancer cell lines pretreated by cold atmospheric plasma. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal-Eldeen, A.M.; Alrehaili, A.A.; Alharthi, A.; Raafat, B.M. Effect of Combined Perftoran and Indocyanine Green-Photodynamic Therapy on HypoxamiRs and OncomiRs in Lung Cancer Cells. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 844104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, S.; Chen, C.; Qian, Z.; Yang, Y. Assays on 3D tumor spheroids for exploring the light dosimetry of photodynamic effects under different gaseous conditions. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202300552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mroz, P.; Yaroslavsky, A.; Kharkwal, G.B.; Hamblin, M.R. Cell death pathways in photodynamic therapy of cancer. Cancers 2011, 3, 2516–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.D.; Brookes, M.J.; Pringle, T.A.; Pal, R.; Tanwani, R.; Burt, A.D.; Knight, J.C.; Kumar, A.T.; Rankin, K.S. Investigating the mechanisms of indocyanine green tumour uptake in sarcoma cell lines and ex vivo human tissue. J. Pathol. 2025, 267, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Dong, S.; Hu, C.; Xiao, J. Targeting clathrin-mediated endocytosis: Recent advances in inhibitor development, mechanistic insights, and therapeutic prospects. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 5843–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. The Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) Effect: The Significance of the Concept and Methods to Enhance Its Application. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, M.A.; Yalamarty, S.S.K.; Filipczak, N.; Parveen, F.; Torchilin, V.P. Recent Advances in Tumor Targeting via EPR Effect for Cancer Treatment. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Chen, G.; Qin, L.; Qu, C.; Dong, X.; Ni, J.; Yin, X. Metal Organic Frameworks as Drug Targeting Delivery Vehicles in the Treatment of Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, W.; Xia, G.; Shao, R. Endocytosis and Organelle Targeting of Nanomedicines in Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 9447–9467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, J.; Wu, F.; Du, S.; Miao, J.; Hu, B.; Olkhovsky, I.A.; et al. Advances in nanocarrier-mediated cancer therapy: Progress in immunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 1927–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnecka-Czapczyńska, M.; Aebisher, D.; Dynarowicz, K.; Krupka-Olek, M.; Cieślar, G.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A. Photodynamic Therapy of Breast Cancer in Animal Models and Their Potential Use in Clinical Trials-Role of the Photosensitizers: A Review. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2023, 28, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.P.; Sinagra, D.; Dip, F.; Rosenthal, R.J.; Mueller, E.A.; Lo Menzo, E.; Rancati, A. Indocyanine green fluorescence versus blue dye, technetium-99M, and the dual-marker combination of technetium-99M + blue dye for sentinel lymph node detection in early breast cancer-meta-analysis including consistency analysis. Surgery 2024, 175, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Shuai, J.; Leng, Z.; Ji, Y. Meta-analysis of the application value of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in guiding sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 43, 103742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, C.F.; Veys, I.; Bormans, A.; Larsimont, D.; Liberale, G. Fluorescence imaging for real-time detection of breast cancer tumors using IV injection of indocyanine green with non-conventional imaging: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies of perioperative imaging technologies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 204, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, P.M.C.; MacKenzie, A.; Filipovic, A.; Koelmeyer, L. Advances in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer-related lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 200, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.L.; Dayaratna, N.; Graham, S.; Azimi, F.; Mak, C.; Pulitano, C.; Warrier, S. Evolution of Indocyanine Green Fluorescence in Breast and Axilla Surgery: An Australasian Experience. Life 2024, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.Y.; Shen, C.; Mi, X.Q.; Pu, Q. The primary application of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in surgical oncology. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1077492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhong, L. Metal Nanoparticles for Photodynamic Therapy: A Potential Treatment for Breast Cancer. Molecules 2021, 26, 6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaseri, H.; Kruger, C.A.; Abrahamse, H. Inorganic Nanoparticles Applied for Active Targeted Photodynamic Therapy of Breast Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, K.; Deng, F.; Deng, W.; Sang, R. Advances in photodynamic therapy and its combination strategies for breast cancer. Acta Biomater. 2025, 205, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, P.; Schwarz, V.; Dobler-Girdziunaite, D.; Hornung, R.; Walt, H.; Degen, A.; Fehr, M. Photodynamic therapy of locoregional breast cancer recurrences using a chlorin-type photosensitizer. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 93, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, R.E.; Allison, R.R.; Sibata, C.; Downie, G.H. Breast cancer with chest wall progression: Treatment with photodynamic therapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2004, 11, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.A.; Hill, S.L.; Rogers, G.S.; Graham, R.A. Efficacy and safety of continuous low-irradiance photodynamic therapy in the treatment of chest wall progression of breast cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 192, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mang, T.S.; Allison, R.; Hewson, G.; Snider, W.; Moskowitz, R. A phase II/III clinical study of tin ethyl etiopurpurin (Purlytin)-induced photodynamic therapy for the treatment of recurrent cutaneous metastatic breast cancer. Cancer J. Sci. Am. 1998, 4, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allison, R.; Mang, T.; Hewson, G.; Snider, W.; Dougherty, D. Photodynamic therapy for chest wall progression from breast carcinoma is an underutilized treatment modality. Cancer 2001, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, K.A.; Bonel, H.M.; Frick, H.; Walt, H.; Steiner, R.A. Photodynamic detection of diseased axillary sentinel lymph node after oral application of aminolevulinic acid in patients with breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 90, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, S.W.; Fingar, V.H.; Coots, C.T.; Wieman, T.J. Photodynamic therapy using mono-L-aspartyl chlorin e6 (Npe6) for the treatment of cutaneous disease: A Phase I clinical study. Clin. Cancer Res. 1998, 4, 2741–2746. [Google Scholar]

- Dimofte, A.; Zhu, T.C.; Hahn, S.M.; Lustig, R.A. In vivo light dosimetry for motexafin lutetium-mediated PDT of recurrent breast cancer. Lasers Surg. Med. 2002, 31, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mytych, W.; Bartusik-Aebisher, D.; Aebisher, D.; Henrykowska, G. Stability and Selectivity of Indocyanine Green Towards Photodynamic Therapy of CRL-2314 Breast Cancer Cells with Minimal Toxicity to HTB-125 Cells. Molecules 2025, 30, 4773. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244773

Mytych W, Bartusik-Aebisher D, Aebisher D, Henrykowska G. Stability and Selectivity of Indocyanine Green Towards Photodynamic Therapy of CRL-2314 Breast Cancer Cells with Minimal Toxicity to HTB-125 Cells. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4773. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244773

Chicago/Turabian StyleMytych, Wiktoria, Dorota Bartusik-Aebisher, David Aebisher, and Gabriela Henrykowska. 2025. "Stability and Selectivity of Indocyanine Green Towards Photodynamic Therapy of CRL-2314 Breast Cancer Cells with Minimal Toxicity to HTB-125 Cells" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4773. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244773

APA StyleMytych, W., Bartusik-Aebisher, D., Aebisher, D., & Henrykowska, G. (2025). Stability and Selectivity of Indocyanine Green Towards Photodynamic Therapy of CRL-2314 Breast Cancer Cells with Minimal Toxicity to HTB-125 Cells. Molecules, 30(24), 4773. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244773