Comparative Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Forms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

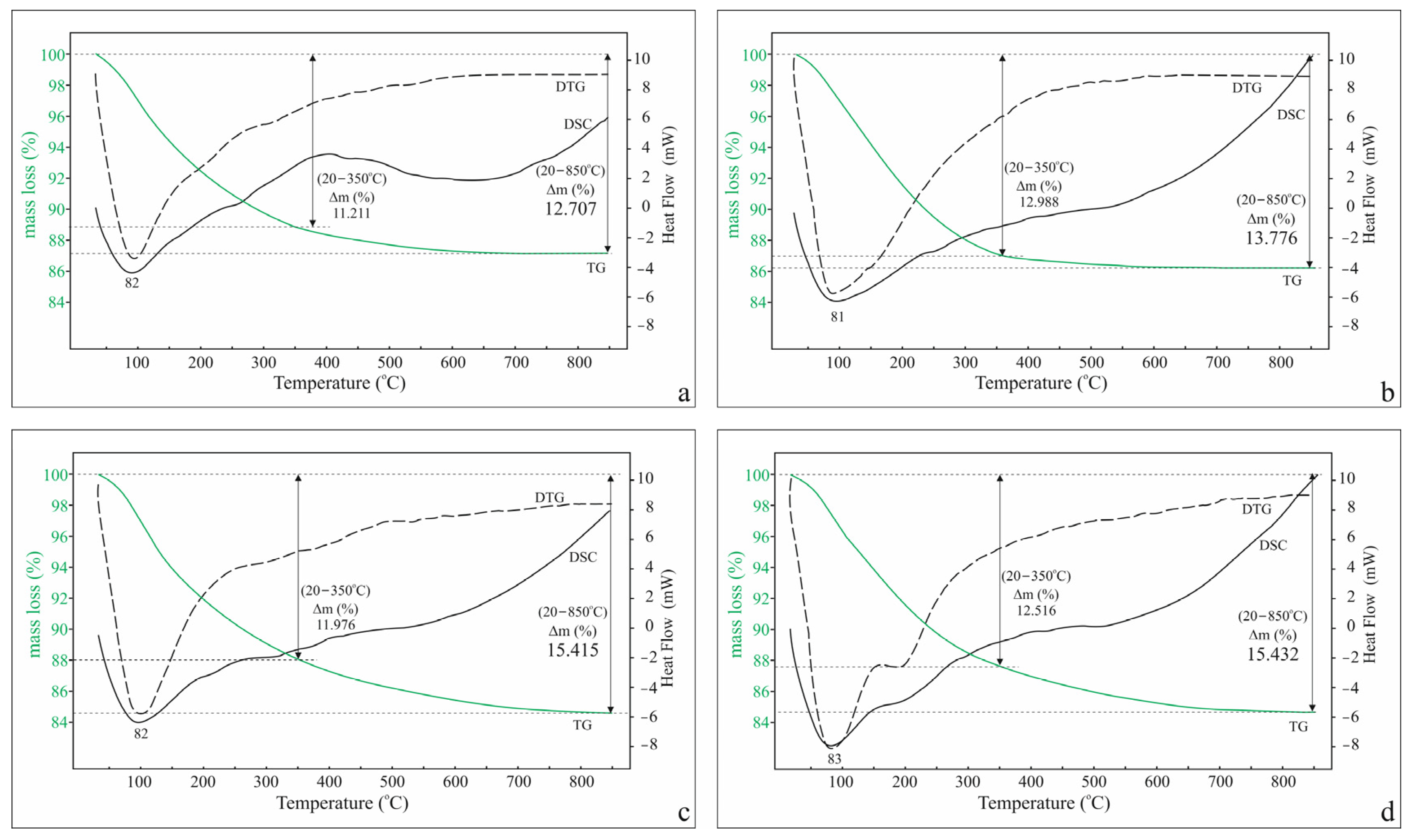

2.1. Standard TG-DSC Study

2.2. Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study

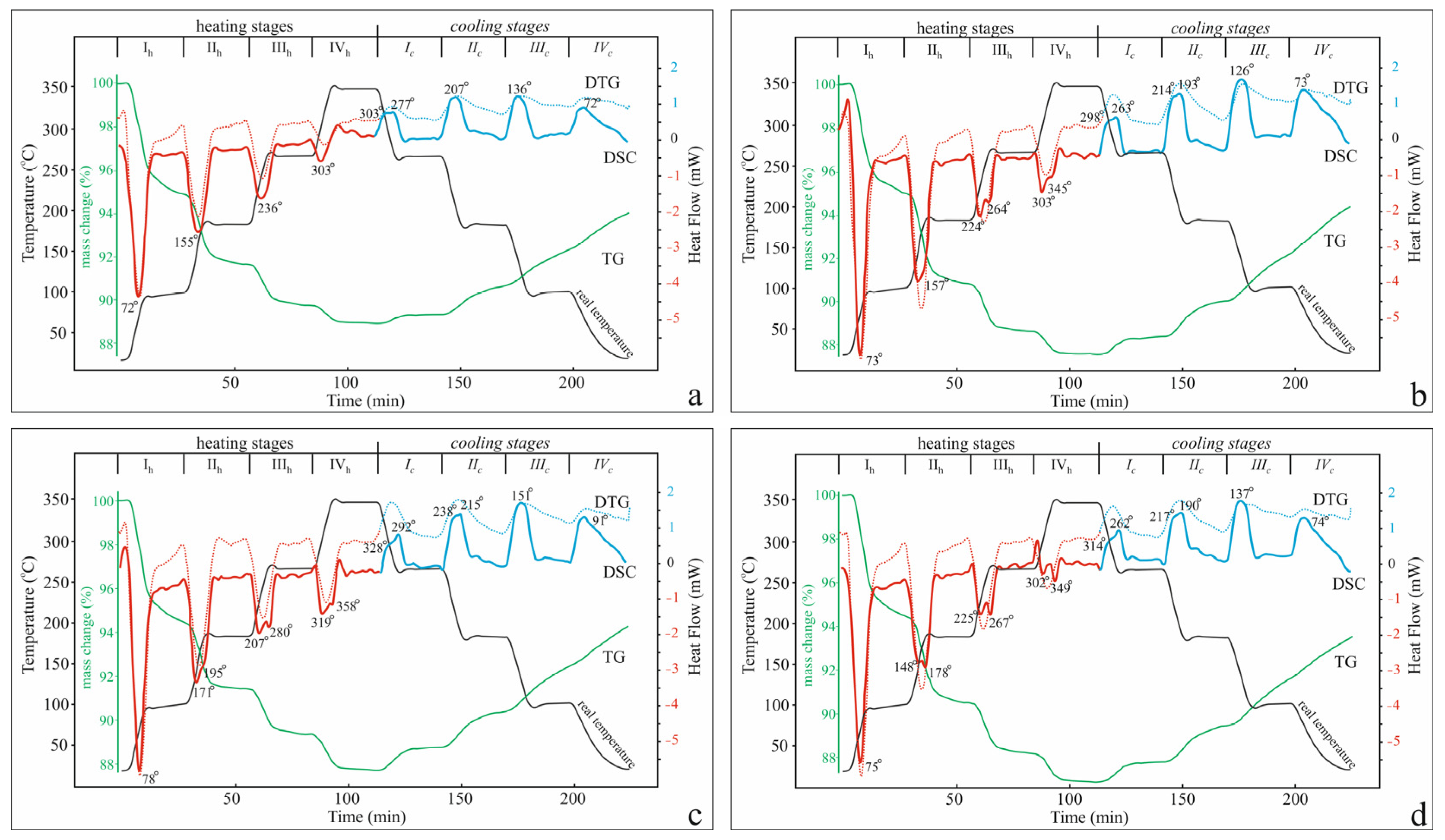

2.2.1. Four-Stage TG-DSC Study

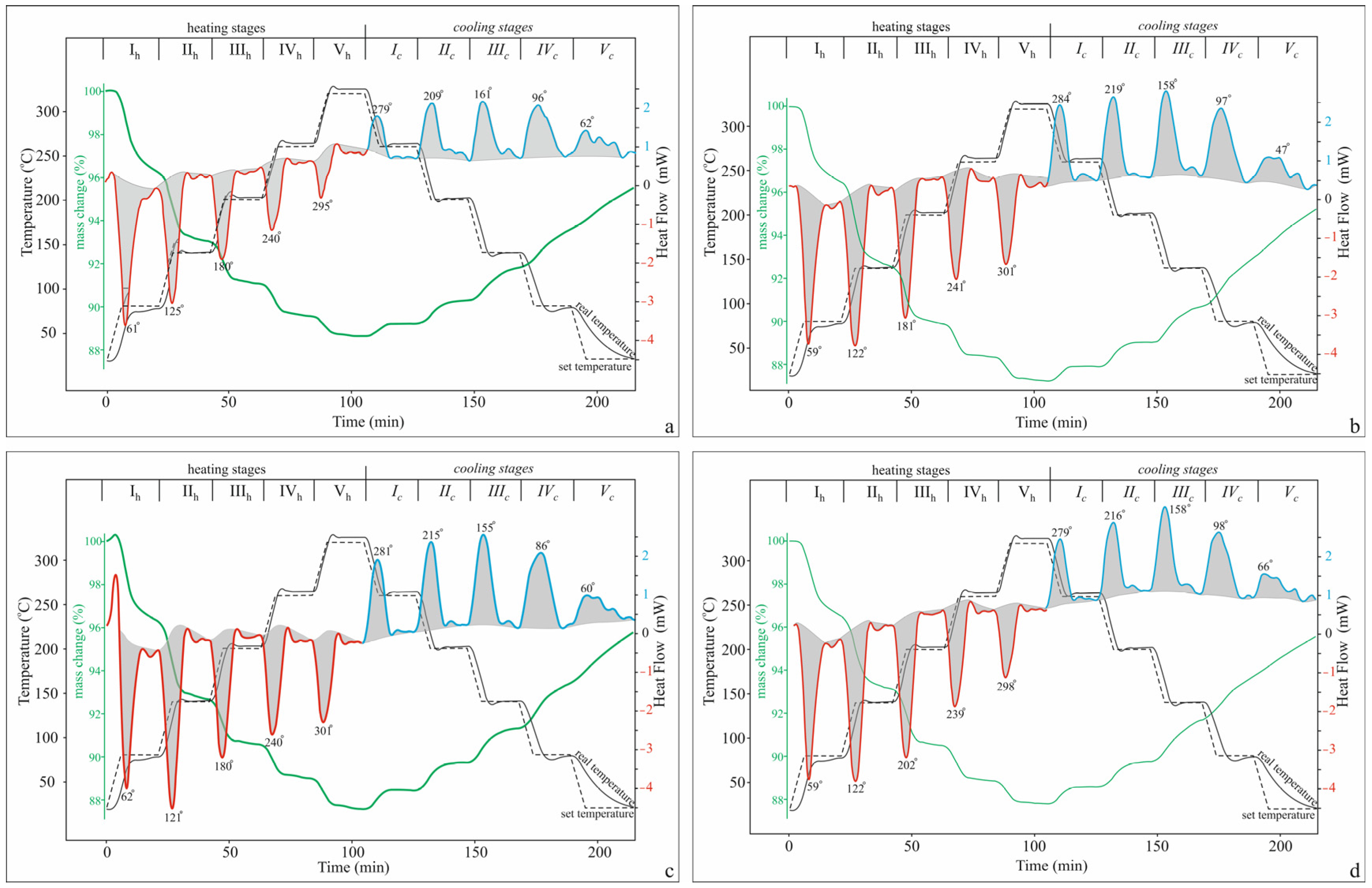

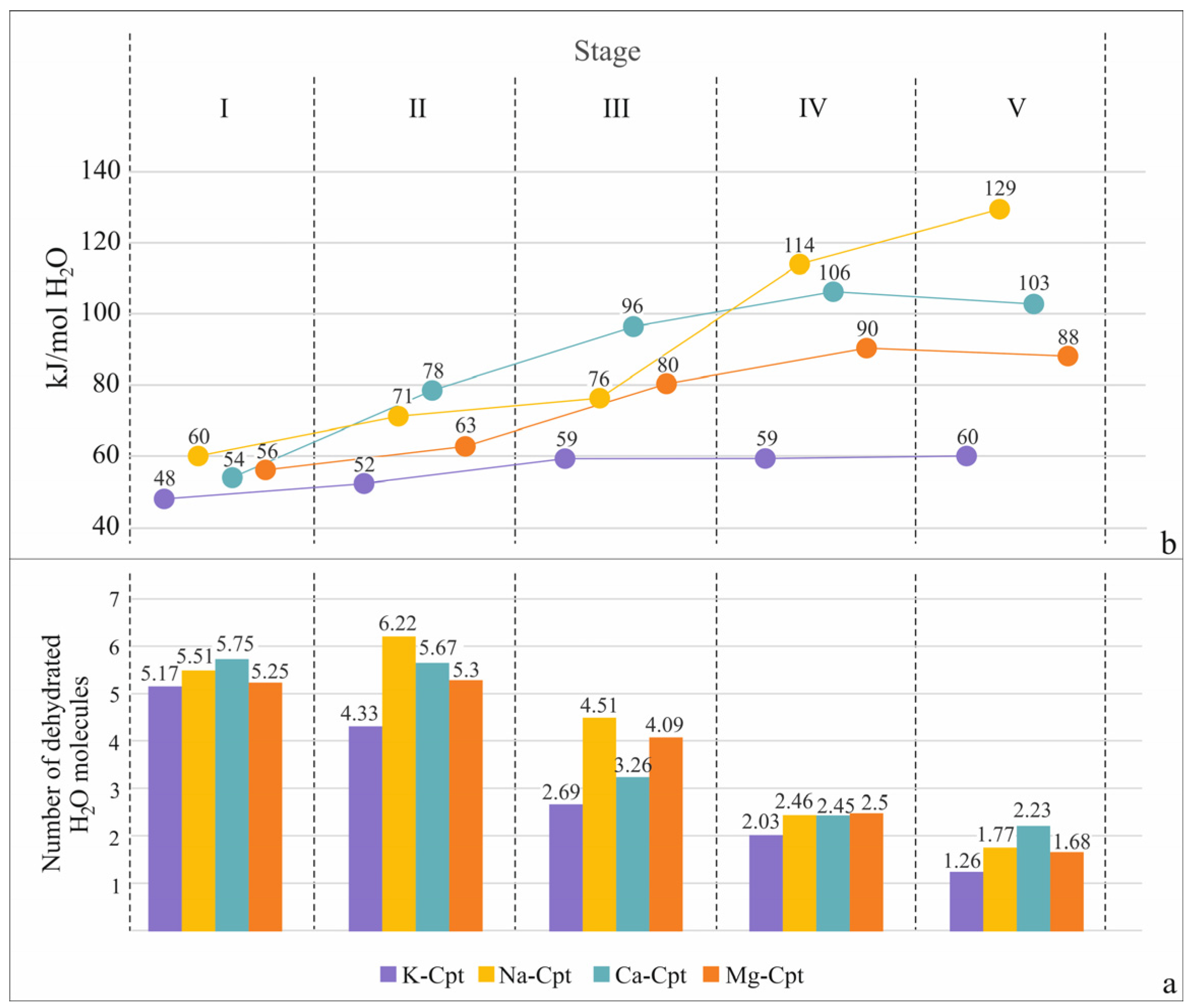

2.2.2. Five-Stage TG-DSC Study

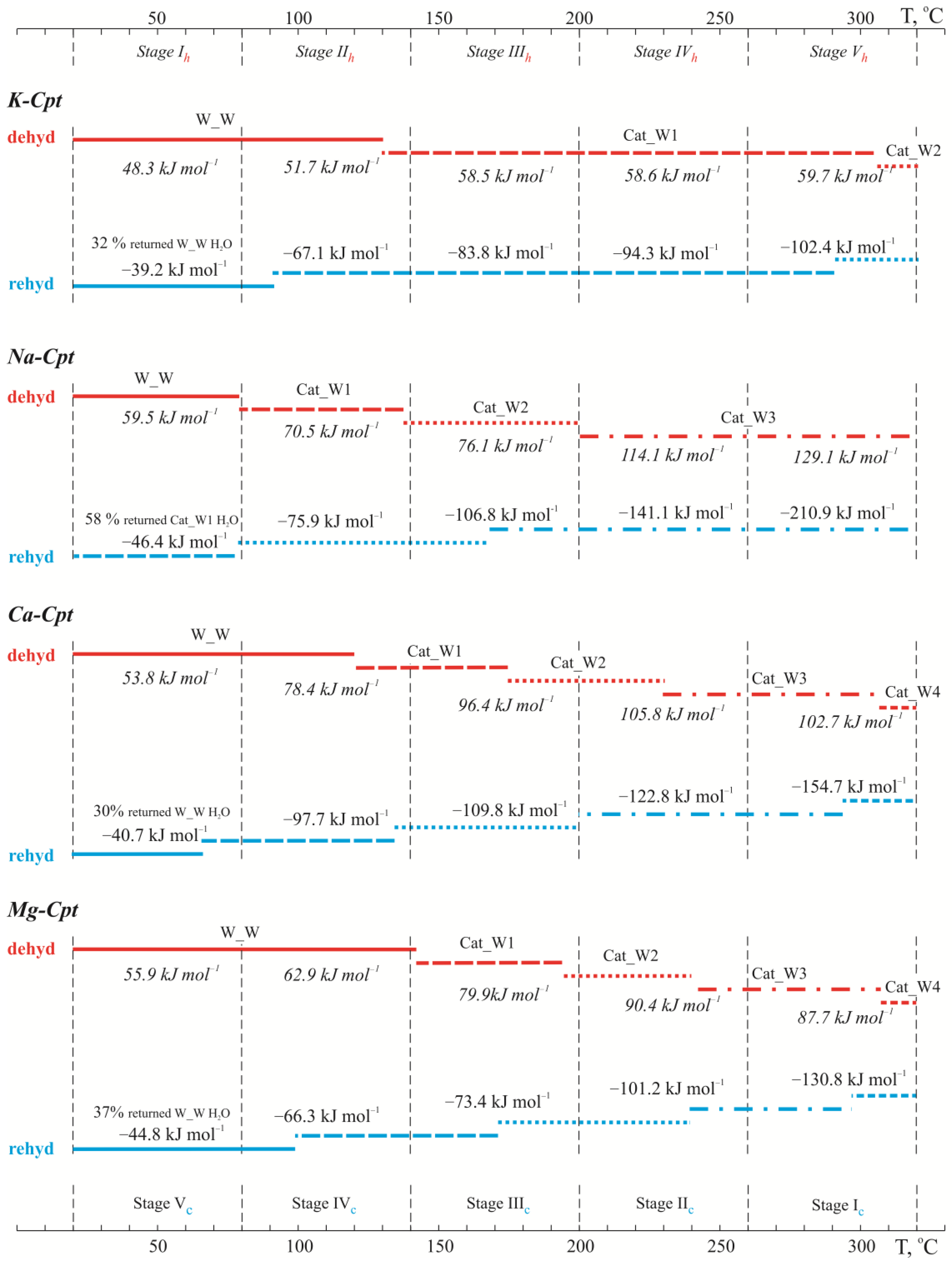

- Dehydration

- Rehydration

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

- As purified: (Na0.61K1.90Ca1.32Mg0.35)[(Al5.83Fe0.06 Si30.12)O72]∙24.1H2O

- K-Cpt: (Na0.64K5.39Ca0.04Mg0.13)[(Al5.76Fe0.05Si30.05)O72]∙17.3H2O

- Na-Cpt: (Na4.65K1.05Ca0.06Mg0.18)[(Al5.53Fe0.06Si30.27)O72]∙21.8H2O

- Ca-Cpt: (Na0.35K0.94Ca2.24Mg0.20)[(Al5.95Fe0.05Si29.96)O72]∙23.9H2O

- Mg-Cpt: (Na0.05K1.4 Ca0.48Mg1.52)[(Al5.97Fe0.07Si30.12)O72]∙23.8H2O

3.2. Methods

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Cpt | clinoptilolite |

| HEU | Heulandite type structure |

| W_W | Water-water assemblages |

| Cat_W | cation–water assemblages |

| TG | Thermogravimetry |

| DTG | Differential Thermogravimetry |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

References

- Breck, D.W. Zeolite Molecular Sieves: Structure, Chemistry and Use; Waley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1974; p. 771. [Google Scholar]

- Gottardi, G.; Galli, E. Natural Zeolites; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; 409p. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitsishvili, G.V.; Andronikashvili, T.G.; Kirov, G.N.; Filizova, L.D. Natural Zeolites; Ellis Harwood Ltd.: London, UK, 1992; p. 295. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster, T. Clinoptilolite-heulandite: Applications and basic research. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 2001, 135, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Iznaga, I.; Shelyapina, M.G.; Petranovskii, V. Ion exchange in natural clinoptilolite: Aspects related to its structure and applications. Minerals 2022, 12, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerlocher, C.; McCusker, L.B.; Olson, D.H. Atlas of Zeolite Framework Types; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 405. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, D.C.; Alberti, A.; Armbruster, T.; Artioli, G.; Galli, E.; Grise, J.B.; Liebau, E.; Mandarino, J.A.; Minato, H.; Nickel, E.H.; et al. Recommended nomenclature for zeolite minerals: Report of the International Mineralogical Association, Commission of New Minerals and Mineral names. Miner. Mag. 1998, 62, 533–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, A.B.; Slaughter, M. Determination and refinement of the structure of heulandite. American Mineralogist. Am. Miner. 1968, 53, 1120–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, K.; Takeuchi, Y. Clinoptilolite: The distribution of potassium atoms and its role in thermal analysis. Z. Kristallogr. 1977, 145, 216–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Takeuchi, K. Distribution of Cations and Water Molecules in the Heulandite-Type Framework. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1986, 28, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, L.L. The cation sieve properties of clinoptilolite. Am. Miner. J. Earth Planet. Mater. 1960, 45, 689–700. [Google Scholar]

- Pabalan, R.T.; Bertetti, F.P. Cation-exchange properties of natural zeolites. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2001, 45, 453–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumpton, F.A. Clinoptilolite redefined. Am. Miner. J. Earth Planet. Mater. 1960, 45, 351–369. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, B.; Sand, L.B. Clinoptilolite from Patagonia: The relationship between clinoptilolite and heulandite. Am. Miner. 1960, 45, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Bish, D.L.; Carey, J.W. Thermal behavior of natural zeolites. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2001, 45, 403–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, D.L. Effects of exchangeable cation composition on the thermal expansion/contraction of clinoptilolite. Clays Clay Miner. 1984, 32, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, E.; Gottardi, G.; Mayer, H.; Preisinger, A.; Passaglia, E. The structure of potassium-exchanged heulandite at 293, 373 and 593 K. Acta Crystallogr. 1983, B39, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobaer, T.M.; Kuribayashi, T.; Komatsu, K.; Kudoh, Y. The partially dehydrated structure of natural heulandite: An in situ high temperature single crystal X-ray diffraction study. J. Miner. Petrol. Sci. 2008, 103, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kudoh, Y.; Takeuchi, Y. Thermal stability of clinoptilolite: The crystal structure at 350 °C. Miner. J. 1983, 11, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, T.; Gunter, M.E. Stepwise dehydration of heulandite-clinoptilolite from Succor Creek Oregon, U.S.A.: A single-crystal X-ray study at 100 K. Am. Miner. 1991, 76, 1872–1883. [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster, T. Dehydration mechanism of clinoptilolite and heulandite; single-crystal X-ray study of Na-poor, Ca-, K-, Mg-rich clinoptilolite at 100 K. Am. Miner. 1993, 78, 260–264. [Google Scholar]

- Bish, D.L. Thermal behavior of natural zeolites. In Natural Zeolites’93: Occurrence, Properties, Use; Ming, D.W., Mumpton, F.A., Eds.; Brockport: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Langella, A.; Pansini, M.; Cerri, G.; Cappelletti, P.; De’ Gennaro, M. Thermal behavior of natural and cation-exchanged clinoptilolite from Sardinia (Italy). Clays Clay Miner. 2003, 51, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alver, B.E.; Sakizci, M.; Yörükogullari, E. Investigation of clinoptilolite rich natural zeolites from Turkey: A combined XRF, TG/DTG, DTA and DSC study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2010, 100, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimowa, L.; Petrova, N.; Tzvetanova, Y.; Petrov, O.; Piroeva, I. Structural features and thermal behavior of ion-exchanged clinoptilolite from Beli Plast deposit (Bulgaria). Minerals 2022, 12, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Dechnik, J.; Szymczak, P.; Handke, B.; Szumera, M.; Stoch, P. Thermal Behavior of Clinoptilolite. Crystals 2024, 14, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.W.; Bish, D.L. Equilibrium in the clinoptilolite-H2O system. Am. Miner. 1996, 81, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrer, R.M. Zeolites and Clay Minerals as Sorbates and Molecular Sieves; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; p. 497. [Google Scholar]

- Ackley, M.; Yang, R. Adsorption characteristics of high-exchange clinoptilolites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1991, 30, 2523–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, S.U.; Yang, R.T.; Buzanowski, M.A. Sorbents for air prepurification in air separation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2000, 55, 4827−4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.K.; Tasker, I.R.; Jurgens, R.; O’Hare, P.A.G. Thermodynamic studies of zeolites: Clinoptilolite. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 1991, 23, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrer, R.M.; Cram, P.J. Heats of immersion of outgassed ion-exchanged zeolites. In Molecular Sieve Zeolites-II; Advances in Chemistry; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1971; Volume 102, pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- Petrova, N.; Kirov, D. Heats of immersion of clinoptilolite and its ion-exchanged forms: A calorimetric study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1995, 43, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.W.; Bish, D.L. Calorimetric measurement of the enthalpy of hydration of clinoptilolite. Clays Clay Miner. 1997, 45, 826–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Mizota, T.; Fujiwara, K. Hydration heats of zeolites for evaluation of heat exchangers. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2001, 64, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Navrotsky, A.; Wilkin, R. Thermodynamics of ion-exchanged and natural clinoptilolite. Am. Miner. 2001, 86, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiseleva, I.; Navrotsky, A.; Belitsky, I.; Fursenko, B. Thermochemical study of calcium zeolites—Heulandite and stilbite. Am. Miner. 2001, 86, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipera, S.J.; Bish, D.L. Equilibrium modeling of clinoptilolite-analcime equilibria at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, USA. Clays Clay Miner. 1997, 45, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, D.L.; Vaniman, D.T.; Chipera, S.J.; Carey, W. The distribution of zeolites and their effects on the performance of a nuclear waste repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, USA. Am. Miner. 2003, 88, 1889–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernev, D.I. Solar energy application of natural zeolites. In Natural Zeolites’78: Occurrence, Properties, Use; Sand, L.B., Mumpton, F.A., Eds.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 474–485. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, H.; Mobedi, M.; Ülkü, S. A review on adsorption heat pump: Problems and solutions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2381–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezgi, C. Design and thermodynamic analysis of waste heat-driven zeolite–water continuous-adsorption refrigeration and heat pump system for ships. Energies 2021, 14, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drebushchak, V. Measurements of heat of zeolite dehydration by scanning heating. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1999, 58, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhoff, P.S.; Wang, J. Isothermal measurement of heats of hydration in zeolites by simultaneous thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry. Clays Clay Miner. 2007, 55, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Stanimirova, T.; Markov, G.; Kirov, G. Desorption–sorption–desorption profile of clinoptilolite in different air media: A DSC-TG study. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2023, 84, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Kirov, G.; Stanimirova, T. A multi-stage DSC-TG methodology for study of zeolite minerals. Rev. Bulg. Geol. Soc. 2024, 85, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

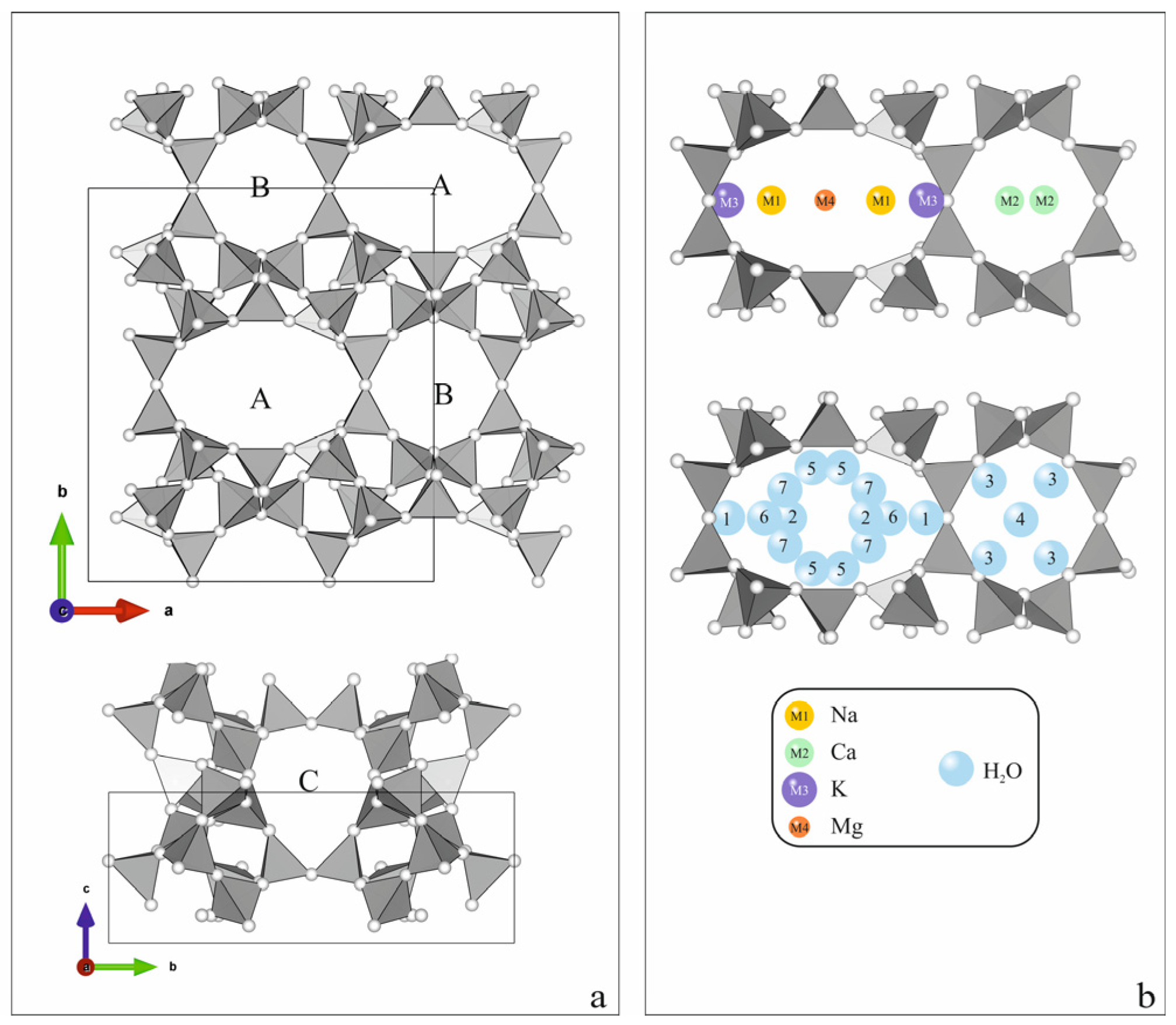

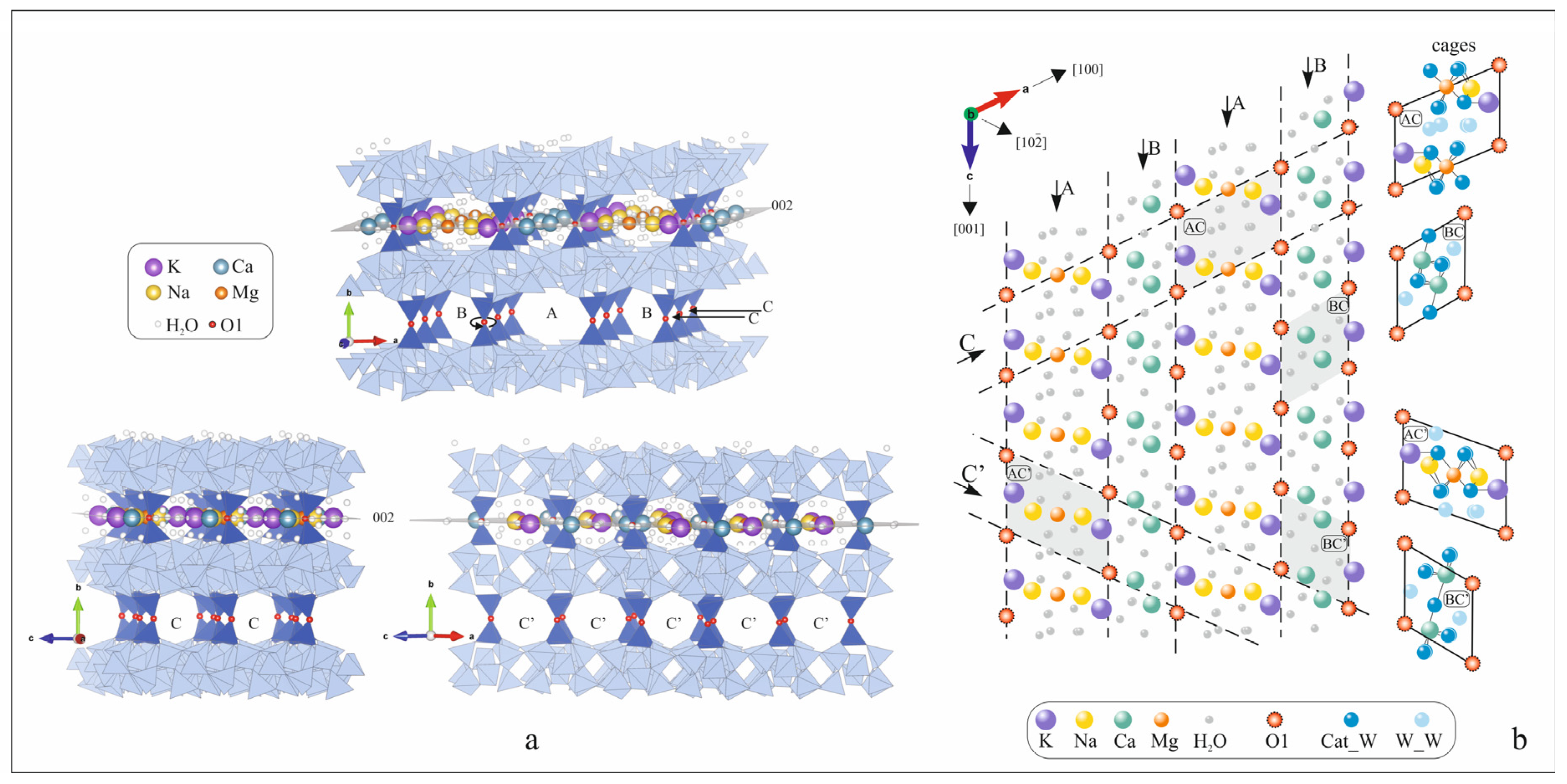

- Kirov, G.; Dimova, L.; Stanimirova, T. Gallery character of porous space and local extra-framework configurations in the HEU-type structure. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 2020, 293, 109792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Armbruster, T. Na, K, Rb, and Cs exchange in heulandite single-crystals: X-ray structure refinements at 100 K. J. Solid State Chem. 1996, 123, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirov, G.; Petrova, N.; Stanimirova, T. Matching of the water states of products and zeolite during contact adsorption drying. Dry. Technol. 2017, 35, 2015–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stage | Temperature Region, °C | K-Cpt | Na-Cpt | Ca-Cpt | Mg-Cpt | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Change (Δm, %) | Mass Change (Δm, %) | Mass Change (Δm, %) | Mass Change (Δm, %) | ||||||

| Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | ||

| I | 20–100 | −5.68 | +1.63 | −5.38 | +2.11 | −5.57 | +1.83 | −5.55 | +1.92 |

| II | 100–180 | −3.21 | +1.72 | −4.24 | +2.24 | −3.09 | +2.09 | −3.96 | +2.34 |

| III | 180–260 | −1.88 | +1.30 | −2.27 | +1.58 | −2.08 | +1.64 | −2.31 | +1.69 |

| IV | 260–340 | −0.84 | +0.40 | −1.29 | +0.77 | −1.68 | +1.09 | −1.32 | +0.98 |

| Total | 20–340 | −11.61 | +5.05 | −13.18 | +6.70 | −12.42 | +6.65 | −13.14 | +6.99 |

| Stage (T, °C) | I (20–80) | II (80–140) | III (140–200) | IV (200–260) | V (260–320) | Total (20–320) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Mode | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) | Δm (%) | Oz (J g−1) |

| K-Cpt | dynamic | 3.28 | 97.6 | 2.87 | 88.7 | 1.80 | 61.7 | 1.33 | 45.6 | 0.83 | 27.5 | 10.11 | 321.1 |

| isotherm | 0.52 | 4.3 | 0.31 | 2.6 | 0.18 | 3.3 | 0.16 | 2.9 | 0.10 | 3.3 | 1.28 | 16.4 | |

| Total | 3.80 | 101.9 | 3.18 | 91.3 | 1.98 | 65.0 | 1.49 | 48.5 | 0.93 | 30.8 | 11.39 | 337.5 | |

| Na-Cpt | dynamic | 2.99 | 113.3 | 3.49 | 148.3 | 2.56 | 112.6 | 1.44 | 90.2 | 1.07 | 71.7 | 11.55 | 539.7 |

| isotherm | 0.50 | 1.7 | 0.44 | 5.7 | 0.29 | 2.5 | 0.11 | 6.8 | 0.12 | 6.5 | 1.46 | 19.5 | |

| Total | 3.49 | 115.0 | 3.93 | 154.0 | 2.85 | 115.1 | 1.55 | 97.0 | 1.19 | 78.2 | 13.01 | 559.2 | |

| Ca-Cpt | dynamic | 3.21 | 100.5 | 3.36 | 153.6 | 1.91 | 106.1 | 1.42 | 85.1 | 1.22 | 70.7 | 11.13 | 516.4 |

| isotherm | 0.50 | 3.3 | 0.30 | 5.5 | 0.19 | 4.8 | 0.16 | 7.8 | 0.22 | 6.8 | 1.36 | 27.7 | |

| Total | 3.71 | 103.8 | 3.65 | 158.9 | 2.10 | 110.9 | 1.58 | 92.9 | 1.44 | 77.5 | 12.49 | 544.1 | |

| Mg-Cpt | dynamic | 2.96 | 103.2 | 3.10 | 116.6 | 2.46 | 100.1 | 1.41 | 75.5 | 1.0 | 49.8 | 10.94 | 445.2 |

| isotherm | 0.45 | 2.6 | 0.34 | 3.6 | 0.18 | 2.4 | 0.21 | 5.2 | 0.09 | 3.3 | 1.27 | 17.0 | |

| Total | 3.41 | 105.8 | 3.44 | 120.2 | 2.64 | 102.5 | 1.62 | 80.7 | 1.09 | 53.1 | 12.00 | 462.2 | |

| Sample | Number of H2O Molecules | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W_W | Cat_W1 | Cat_W2 | Cat_W3 | Cat_W4 | Cat_W5 | Cat_W6 | Total H2O | |

| K-Cpt | 9.01 | 6.20 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 17.3 |

| Coordinated at: | ||||||||

| K+ Na+ Ca2+ Mg2+ | 5.39 0.64 0.04 0.13 | 0.64 0.04 0.13 | 0.64 0.04 0.13 | 0.04 0.13 | 0.04 0.13 | 0.13 | ||

| Na-Cpt | 5.42 | 5.94 | 4.89 | 4.89 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 21.8 |

| Coordinated at: | ||||||||

| K+ Na+ Ca2+ Mg2+ | 1.05 4.65 0.06 0.18 | 4.65 0.06 0.18 | 4.65 0.06 0.18 | 0.06 0.18 | 0.06 0.18 | 0.18 | ||

| Ca-Cpt | 9.51 | 3.73 | 2.79 | 2.79 | 2.44 | 2.44 | 0.20 | 23.9 |

| Coordinated at: | ||||||||

| K+ Na+ Ca2+ Mg2+ | 0.94 0.35 2.24 0.20 | 0.35 2.24 0.20 | 0.35 2.24 0.20 | 2.24 0.20 | 2.24 0.20 | 0.20 | ||

| Mg-Cpt | 10.73 | 3.45 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 2.0 | 2.00 | 1.52 | 23.8 |

| Coordinated at: | ||||||||

| K+ Na+ Ca2+ Mg2+ | 1.40 0.05 0.48 1.52 | 0.05 0.48 1.52 | 0.05 0.48 1.52 | 0.48 1.52 | 0.48 1.52 | 1.52 | ||

| Sample H2O Type Theor. Model | nH2O in Theor. Model | Experimental Data for Stages | H2O | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I 25–80 °C | II 80–140 °C | III 140–200 °C | IV 200–260 °C | V 260–320 °C | Total 25–320 °C | Remained in the Structure | |||||||

| nH2O | ΔH, kJ mol−1 | nH2O | ΔH, kJ mol−1 | nH2O | ΔH, kJ mol−1 | nH2O | ΔH, kJ mol−1 | nH2O | ΔH, kJ mol−1 | nH2O | |||

| K-Cpt | 5.17 | 48.3 | 4.33 | 51.7 | 2.69 | 58.5 | 2.03 | 58.6 | 1.26 | 59.7 | 15.48 | 1.82 | |

| W_W | 9.01 | 5.17 | 3.84 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W1 | 6.20 | 0.49 | 2.69 | 2.03 | 0.99 | ||||||||

| Cat_W2 | 0.81 | 0.27 | 0.54 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W3–6 | 1.28 | 1.28 | |||||||||||

| Na-Cpt | 5.52 | 59.5 | 6.22 | 70.5 | 4.51 | 76.1 | 2.46 | 114.1 | 1.77 | 129.1 | 20.48 | 1.32 | |

| W_W | 5.42 | 5.42 | |||||||||||

| Cat_W1 | 5.94 | 0.10 | 5.84 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W2 | 4.89 | 0.38 | 4.51 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W3 | 4.89 | 2.46 | 1.77 | 0.67 | |||||||||

| Cat_W4–6 | 0.65 | 0.65 | |||||||||||

| Ca-Cpt | 5.75 | 53.8 | 5.67 | 78.4 | 3.26 | 96.4 | 2.45 | 105.8 | 2.23 | 102.7 | 19.36 | 4.54 | |

| W_W | 9.51 | 5.75 | 3.76 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W1 | 3.73 | 1.91 | 1.82 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W2 | 2.79 | 1.44 | |||||||||||

| Cat_W3 | 2.79 | 1.10 | 1.69 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W4–6 | 5.08 | 0.54 | 4.54 | ||||||||||

| Mg-Cpt | 5.26 | 55.9 | 5.31 | 62.9 | 4.07 | 79.9 | 2.50 | 90.4 | 1.68 | 87.7 | 18.82 | 4.98 | |

| W_W | 10.73 | 5.26 | 5.30 | 0.17 | |||||||||

| Cat_W1 | 3.45 | 3.45 | |||||||||||

| Cat_W2 | 2.05 | 0.46 | 1.59 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W3 | 2.05 | 0.91 | 1.14 | ||||||||||

| Cat_W4–6 | 5.52 | 0.54 | 4.98 | ||||||||||

| Dehydration | Rehydration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Initial nH2O | Leaved nH2O | Degree of Dehydration, % | Returned nH2O | % of Rehydration (Compared to Dehydrated Samples) |

| K-Cpt | 17.3 | 15.48 | 90 | 9.35 | 60 |

| Na-Cpt | 21.8 | 20.48 | 94 | 12.55 | 61 |

| Ca-Cpt | 23.9 | 19.36 | 81 | 12.73 | 66 |

| Mg-Cpt | 23.8 | 18.82 | 79 | 12.01 | 64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanimirova, T.; Petrova, N.; Kirov, G. Comparative Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Forms. Molecules 2025, 30, 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244770

Stanimirova T, Petrova N, Kirov G. Comparative Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Forms. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244770

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanimirova, Tsveta, Nadia Petrova, and Georgi Kirov. 2025. "Comparative Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Forms" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244770

APA StyleStanimirova, T., Petrova, N., & Kirov, G. (2025). Comparative Multi-Stage TG-DSC Study of K+, Na+, Ca2+ and Mg2+-Exchanged Clinoptilolite Forms. Molecules, 30(24), 4770. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244770