Cytotoxic Curvalarol C and Other Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Identification of the Strain KMM 4696

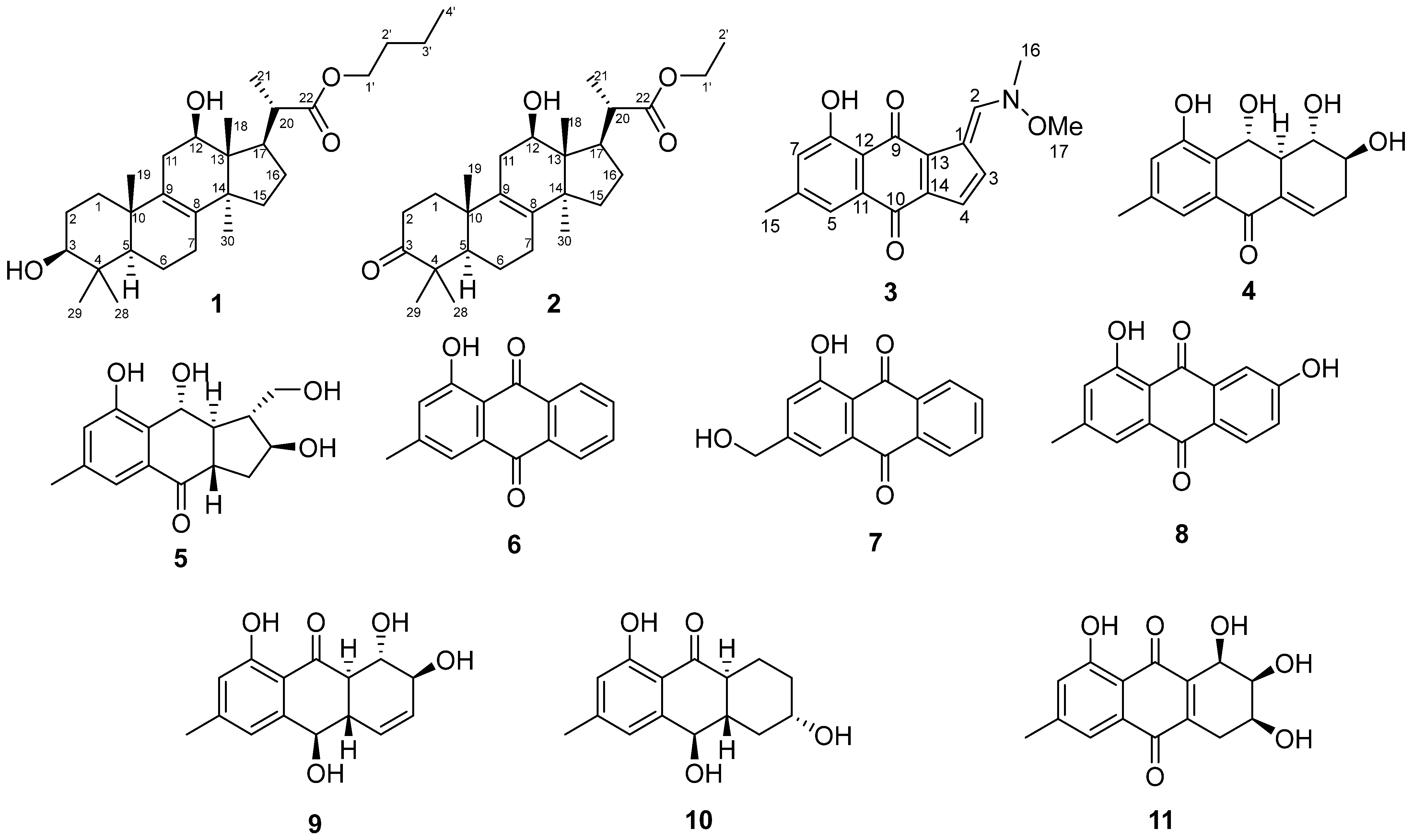

2.2. The Isolation and Structure Elucidation of Individual Compounds from A. cruciatus KMM 4696 Fermented with KI

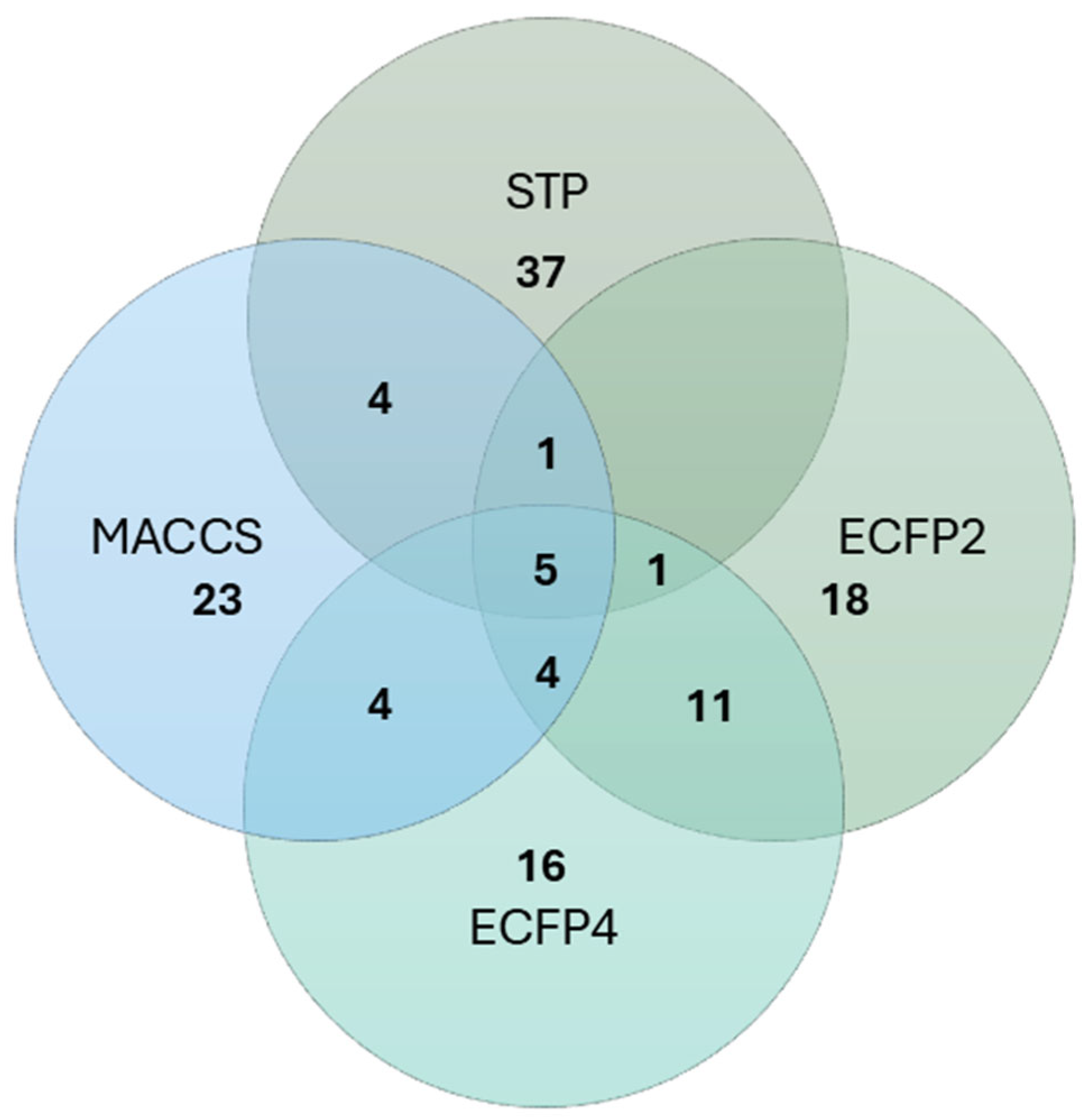

2.3. Bioactivity of Curvalarol C (1)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

3.2. Fungal Strain

3.3. DNA Extraction and Amplification

3.4. Multi-Locus Phylogenetic Analysis

3.5. Cultivation and Extraction of Fungus

3.6. HPLC MS

3.7. Isolation of Individual Compounds

3.8. Spectral Data

3.9. Bioassays

3.9.1. Antimicrobial and Biofilm Formation Assay

3.9.2. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

3.9.3. Cell Viability Assay

3.9.4. Colony Formation Assay

3.9.5. EdU Incorporation Assay

3.9.6. Statistical Data Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinedo-Rivilla, C.; Aleu, J.; Durán-Patrón, R. Cryptic Metabolites from Marine-Derived Microorganisms Using OSMAC and Epigenetic Approaches. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, H.; Rotinsulu, H.; Narita, R.; Takahashi, R.; Namikoshi, M. Induced Production of Halogenated Epidithiodiketopiperazines by a Marine-Derived Trichoderma cf. brevicompactum with Sodium Halides. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 2319–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureram, S.; Kesornpun, C.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P. Directed biosynthesis through biohalogenation of secondary metabolites of the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus unguis. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, F.; Luo, M.; Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Ju, J. Halogenated Anthraquinones from the Marine-Derived Fungus Aspergillus sp. SCSIO F063. J. Nat. Prod. 2012, 75, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekera, K.; Mahidol, C.; Ruchirawat, S.; Kittakoop, P. Metabolite diversification by cultivation of the endophytic fungus Dothideomycete sp. in halogen containing media: Cultivation of terrestrial fungus in seawater. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 2868–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.G.; Pang, K.-L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Jin, J.; Devadatha, B.; Sadaba, R.B.; Apurillo, C.C.; Hyde, K.D. Updates on the classification and numbers of marine fungi. Bot. Mar. 2023, 66, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulder, T.A.M.; Hong, H.; Correa, J.; Egereva, E.; Wiese, J.; Imhoff, J.F.; Gross, H. Isolation, Structure Elucidation and Total Synthesis of Lajollamide A from the Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 2912–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igboeli, H.A.; Marchbank, D.H.; Correa, H.; Overy, D.; Kerr, R.G. Discovery of Primarolides A and B from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus Using Osmotic Stress and Treatment with Suberoylanilide Hydroxamic Acid. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuravleva, O.I.; Oleinikova, G.K.; Antonov, A.S.; Kirichuk, N.N.; Pelageev, D.N.; Rasin, A.B.; Menshov, A.S.; Popov, R.S.; Kim, N.Y.; Chingizova, E.A.; et al. New Antibacterial Chloro-Containing Polyketides from the Alga-Derived Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuravleva, O.I.; Chingizova, E.A.; Oleinikova, G.K.; Starnovskaya, S.S.; Antonov, A.S.; Kirichuk, N.N.; Menshov, A.S.; Popov, R.S.; Kim, N.Y.; Berdyshev, D.V.; et al. Anthraquinone Derivatives and Other Aromatic Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696 and Their Effects against Staphylococcus aureus. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebert, G.L. WARDOMYCES AND ASTEROMYCES. Can. J. Bot. 1962, 40, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Garcia, D.; García, D.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Gené, J. Two Novel Genera, Neostemphylium and Scleromyces (Pleosporaceae) from Freshwater Sediments and Their Global Biogeography. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Lo, C.-T.; Chen, C.; Liu, M.-Y.; Chen, J.-H.; Peng, K.-C. Efficient isolation of anthraquinone-derivatives from Trichoderma harzianum ETS 323. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2007, 70, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrebola, M.L.; Ringbom, T.; Verpoorte, R. Anthraquinones from Isoplexis isabelliana cell suspension cultures. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1283–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imre, S.; Sar, S.; Thomson, R.H. Anthraquinones in Digitalis species. Phytochemistry 1976, 15, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, W.d.S.; Pupo, M.T. Novel anthraquinone derivatives produced by Phoma sorghina, an endophyte found in association with the medicinal plant Tithonia diversifolia (Asteraceae). J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2006, 17, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, A.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Ding, G.; Sun, L.; Li, L.; Dai, M. Anthraquinones from the saline-alkali plant endophytic fungus Eurotium rubrum. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 1138–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Huo, J.; Kurtán, T.; Mándi, A.; Antus, S.; Tang, H.; Draeger, S.; Schulz, B.; Hussain, H.; Krohn, K.; et al. Structural and Stereochemical Studies of Hydroxyanthraquinone Derivatives from the Endophytic Fungus Coniothyrium sp. Chirality 2012, 25, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ondeyka, J.G.; Zink, D.L.; Basilio, A.; Vicente, F.; Collado, J.; Platas, G.; Huber, J.; Dorso, K.; Motyl, M.; et al. Isolation, structure and antibacterial activity of pleosporone from a pleosporalean ascomycete discovered by using antisense strategy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2162–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.-Y.; Li, J.-S.; Qi, H.; Xi, F.-Y.; Xiang, W.-S.; Wang, J.-D.; Wang, X.-J. Two new pentanorlanostane metabolites from a soil fungus Curvularia borreriae strain HS-FG-237. J. Antibiot. 2013, 66, 735–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolesnikova, S.A.; Lyakhova, E.G.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Pushilin, M.A.; Afiyatullov, S.S.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Minh, C.V.; Stonik, V.A. Isolation, structures, and biological activities of triterpenoids from a Penares sp. marine sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 1746–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhushnaya, A.B.; Kolesnikova, S.A.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Lyakhova, E.G.; Menshov, A.S.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Popov, R.S.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Ivanchina, N.V. Rhabdastrellosides A and B: Two New Isomalabaricane Glycosides from the Marine Sponge Rhabdastrella globostellata, and Their Cytotoxic and Cytoprotective Effects. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezaire, A.; Marchand, C.H.; Vallet, M.; Ferrand, N.; Chaouch, S.; Mouray, E.; Larsen, A.K.; Sabbah, M.; Lemaire, S.D.; Prado, S.; et al. Secondary Metabolites from the Culture of the Marine-derived Fungus Paradendryphiella salina PC 362H and Evaluation of the Anticancer Activity of Its Metabolite Hyalodendrin. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grove, J.F. 23,24,25,26,27-Pentanorlanost-8-en-3β,22-diol from Verticillium lecanii. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 1721–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoe, T.; Okada, H.; Itabashi, T.; Nozawa, K.; Okada, K.; Campos Takaki, G.M.d.; Fukushima, K.; Miyaji, M.; Kawai, K.-I. A New Pentanorlanostane Derivative, Cladosporide A, as a Characteristic Antifungal Agent against Aspergillus fumigatus, Isolated from Cladosporium sp. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1422–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoe, T.; Okamoto, S.; Nozawa, K.; Kawai, K.-I.; Okada, K.; Campos Takaki, G.M.D.; Fukushima, K.; Miyaji, M. New Pentanorlanostane Derivatives, Cladosporide B-D, as Characteristic Antifungal Agents Against Aspergillus fumigatus, Isolated from Cladosporium sp. J. Antibiot. 2001, 54, 747–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-Q.; Wang, C.-F.; Li, Y.; Luo, H.-R.; Qiu, M.-H. Isolation and Bioactivity Evaluation of Terpenoids from the Medicinal Fungus Ganoderma sinense. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silchenko, A.S.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Avilov, S.A.; Andryjaschenko, P.V.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Martyyas, E.A.; Kalinin, V.I. Triterpene Glycosides from the Sea Cucumber Eupentacta Fraudatrix. Structure and Biological Action of Cucumariosides I1, I3, I4, Three New Minor Disulfated Pentaosides. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silchenko, A.S.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Avilov, S.A.; Andryjaschenko, P.V.; Dmitrenok, P.S.; Martyyas, E.A.; Kalinin, V.I. Triterpene Glycosides from the Sea Cucumber Eupentacta fraudatrix. Structure and Cytotoxic Action of Cucumariosides A2, A7, A9, A10, A11, A13 and A14, Seven New Minor Non-Sulfated Tetraosides and an Aglycone with an Uncommon 18-Hydroxy Group. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avilov, S.A.; Kalinin, V.I.; Makarieva, T.N.; Stonik, V.A.; Kalinovsky, A.I.; Rashkes, Y.W.; Milgrom, Y.M. Structure of Cucumarioside G2, a Novel Nonholostane Glycoside from the Sea Cucumber Eupentacta fraudatrix. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.-J.; Dong, J.; Che, Y.-J.; Zhu, M.-F.; Wen, M.; Wang, N.-N.; Wang, S.; Lu, A.-P.; Cao, D.-S. TargetNet: A web service for predicting potential drug–target interaction profiling via multi-target SAR models. J. Comput. Mol. Des. 2016, 30, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhidkova, E.M.; Savina, E.D.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Lesovaya, E.A. Marine-Derived Steroids for Cancer Treatment: Search for Potential Selective Glucocorticoid Receptor Agonists/Modulators (SEGRAMs). Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi Duy Ngoc, N.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Thi Hoai Trinh, P.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Thi Dieu, T.V.; Savagina, A.D.; Minin, A.; Thinh, P.D.; Khanh, H.H.N.; Thi Thanh Van, T.; et al. Secondary metabolites of Vietnamese marine fungus Penicillium chermesinum 2104NT-1.3 and their cardioprotective activity. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 104003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, H.E.; Kotlyar, V.; Nudelman, A. NMR Chemical Shifts of Common Laboratory Solvents as Trace Impurities. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 7512–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholin, C.A.; Herzog, M.; Sogin, M.; Anderson, D.M. Identification of Group-and Strain-Specific Genetic Markers for Globally Distributed Alexandrium (Dinophyceae). II. Sequence Analysis of A Fragment of the LSU rRNA gene. J. Phycol. 1994, 30, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwood, H.J.; Olsen, G.J.; Sogin, M.L. The small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene sequences from the hypotrichous ciliates Oxytricha nova and Stylonychia pustulata. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1985, 2, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belousova, E.B.; Zhuravleva, O.I.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Oleynikova, G.K.; Antonov, A.S.; Kirichuk, N.N.; Chausova, V.E.; Khudyakova, Y.V.; Menshov, A.S.; Popov, R.S.; et al. New Anti-Hypoxic Metabolites from Co-Culture of Marine-Derived Fungi Aspergillus carneus KMM 4638 and Amphichorda sp. KMM 4639. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterenko, L.E.; Popov, R.S.; Zhuravleva, O.I.; Kirichuk, N.N.; Chausova, V.E.; Krasnov, K.S.; Pivkin, M.V.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Isaeva, M.P.; Yurchenko, A.N. A Study of the Metabolic Profiles of Penicillium dimorphosporum KMM 4689 Which Led to Its Re-Identification as Penicillium hispanicum. Fermentation 2023, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. High-Throughput Assessment of Bacterial Growth Inhibition by Optical Density Measurements. Curr. Protoc. Chem. Biol. 2010, 2, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kifer, D.; Mužinić, V.; Klarić, M.Š. Antimicrobial potency of single and combined mupirocin and monoterpenes, thymol, menthol and 1,8-cineole against Staphylococcus aureus planktonic and biofilm growth. J. Antibiot. 2016, 69, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Zhao, N.; Sheng, D.; Hou, J.; Hao, C.; Yang, X.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, S.; Han, Z.; Wei, L.; et al. Inhibition of Growth and Metastasis of Colon Cancer by Delivering 5-Fluorouracil-loaded Pluronic P85 Copolymer Micelles. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U. Nuclei Instance Segmentation and Classification in Histopathology Images with Stardist. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging Challenges (ISBIC), Kolkata, India, 28–31 March 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, D.R.; Swain-Bowden, M.J.; Lucas, A.M.; Carpenter, A.E.; Cimini, B.A.; Goodman, A. CellProfiler 4: Improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, mult | δH (J in Hz) | δC, mult | δH (J in Hz) | δC, mult | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 36.6, CH2 | 1.71, m 1.22, m | 36.9, CH2 | 1.99, m 1.64, m | 120.4, C | |

| 2 | 28.6, CH2 | 1.62, m | 34.9, CH2 | 2.55, m 2.38, m | 161.0, CH | 8.40, d (14.5) |

| 3 | 78.5, CH | 3.14, t (7.9) | 216.2, C | 133.7, CH | 6.99, d (3.7) | |

| 4 | 39.6, C | 47.7, C | 119.2, CH | 6.78, d (3.8) | ||

| 5 | 51.4, CH | 1.05, m | 52.0, CH | 1.63, m | 120.5, CH | 7.43, s |

| 6 | 26.9, CH2 | 2.04 (overlapped) | 20.1, CH2 | 1.62, m 1.67, m | 147.0, C | |

| 7 | 30.3, CH2 | 1.29 (overlapped) | 26.8, CH2 | 2.10, m | 123.5, CH | 6.94, s |

| 8 | 134.3, C | 135.9, C | 163.1, C | |||

| 9 | 137.4, C | 135.6, C | 184.6, C | |||

| 10 | 37.7, C | 37.7, C | 181.2, C | |||

| 11 | 34.7, CH2 | 2.54, ddt (18.4, 8.5, 2.5) 1.83, m | 34.5, CH2 | 2.32, m | 136.0, C | |

| 12 | 71.7, CH | 4.08, m | 71.7, CH | 4.10, brs | 115.7, C | |

| 13 | 52.8, C | 52.8, C | 124.2, C | |||

| 14 | 49.7, C | 49.9, C | 137.8, C | |||

| 15 | 31.8, CH2 | 1.19, brs | 32.0, CH2 | 1.20, m 1.72, m | 21.8, CH3 | 2.39, s |

| 16 | 26.4, CH2 | 1.87, m 1.66, m | 26.3, CH2 | 1.88, m 1.72, m | 53.9, CH3 | 3.95, s |

| 17 | 49.7, CH | 2.10, dt (9.5,7.8) | 49.9, CH | 2.14, m | 61.3, CH3 | 3.95, s |

| 18 | 10.2, CH3 | 0.72, s | 10.4, CH3 | 0.75, s | ||

| 19 | 19.6, CH3 | 1.02, s | 19.0, CH3 | 1.14, s | ||

| 20 | 42.4, CH | 2.65, quintet (7.1) | 42.3, CH | 2.66, t (7.0) | ||

| 21 | 19.6, CH3 | 1.29, d (7.0) | 19.5, CH3 | 1.28, d (6.8) | ||

| 22 | 177.9, C | 177.9, C | ||||

| 28 | 28.5, CH3 | 0.98, brs | 26.7, CH3 | 1.05, s | ||

| 29 | 16.1, CH3 | 0.80, s | 21.5, CH3 | 1.03, s | ||

| 30 | 24.3, CH3 | 0.93, brs | 24.4, CH3 | 0.96, s | ||

| 1′ | 64.0, CH2 | 4.01, t (6.6) | 60.1, CH2 | 4.06, quintet (7.0) | ||

| 2′ | 31.5, CH2 | 1.60, brs | 14.6, CH3 | 1.20, m | ||

| 3′ | 19.9, CH2 | 1.4, sextet | ||||

| 4′ | 14.0, CH3 | 0.92, t (7.4) | ||||

| 8-OH | 12.82, s | |||||

| Species | Strain Number | GenBank Accession Number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | TEF1 | ||

| Asteromyces cruciatus | CBS 171.63T | MH858254 | MH869856 | ON542234 |

| Asteromyces cruciatus | KMM 4696 | PP825141 | PP825359 | PP845345 |

| Exserohilum monoceras | CBS 239.77 | LT837474 | LT883405 | |

| Exserohilum rostratum | CBS 128061 | KT265240 | MH877986 | |

| Exserohilum turcicum | CBS 387.58 | MH857820 | LT883412 | |

| Gibbago trianthemae | NFCCI 1886 | HM448998 | MH870931 | |

| Neocamarosporium goegapense | CPC 23676T | KJ869163 | KJ869220 | |

| Neostemphylium polymorphum | FMR 17886T | OU195609 | OU195892 | ON368192 |

| Paradendriphyella arinariae | CBS 181.58T | MH857747 | KC793338 | |

| Paradendriphyella salina | CBS 302.84T | MH873443 | KC584325 | KC584709 |

| Stemphylium botryosum | CBS 714.68T | MH859208 | MH870931 | KC584729 |

| Stemphylium lycopersici | CNU 070067 | JF417683 | JX213347 | |

| Stemphylium vesicarium | CBS 191.86 | MH861935 | JX681120 | KC584731 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nesterenko, L.E.; Yurchenko, E.A.; Zhuravleva, O.I.; Oleinikova, G.K.; Kirichuk, N.N.; Popov, R.S.; Chausova, V.E.; Drozdov, K.A.; Chingizova, E.A.; Isaeva, M.P.; et al. Cytotoxic Curvalarol C and Other Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696. Molecules 2025, 30, 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244772

Nesterenko LE, Yurchenko EA, Zhuravleva OI, Oleinikova GK, Kirichuk NN, Popov RS, Chausova VE, Drozdov KA, Chingizova EA, Isaeva MP, et al. Cytotoxic Curvalarol C and Other Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244772

Chicago/Turabian StyleNesterenko, Liliana E., Ekaterina A. Yurchenko, Olesya I. Zhuravleva, Galina K. Oleinikova, Natalya N. Kirichuk, Roman S. Popov, Viktoria E. Chausova, Konstantin A. Drozdov, Ekaterina A. Chingizova, Marina P. Isaeva, and et al. 2025. "Cytotoxic Curvalarol C and Other Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244772

APA StyleNesterenko, L. E., Yurchenko, E. A., Zhuravleva, O. I., Oleinikova, G. K., Kirichuk, N. N., Popov, R. S., Chausova, V. E., Drozdov, K. A., Chingizova, E. A., Isaeva, M. P., & Yurchenko, A. N. (2025). Cytotoxic Curvalarol C and Other Compounds from Marine Fungus Asteromyces cruciatus KMM 4696. Molecules, 30(24), 4772. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244772