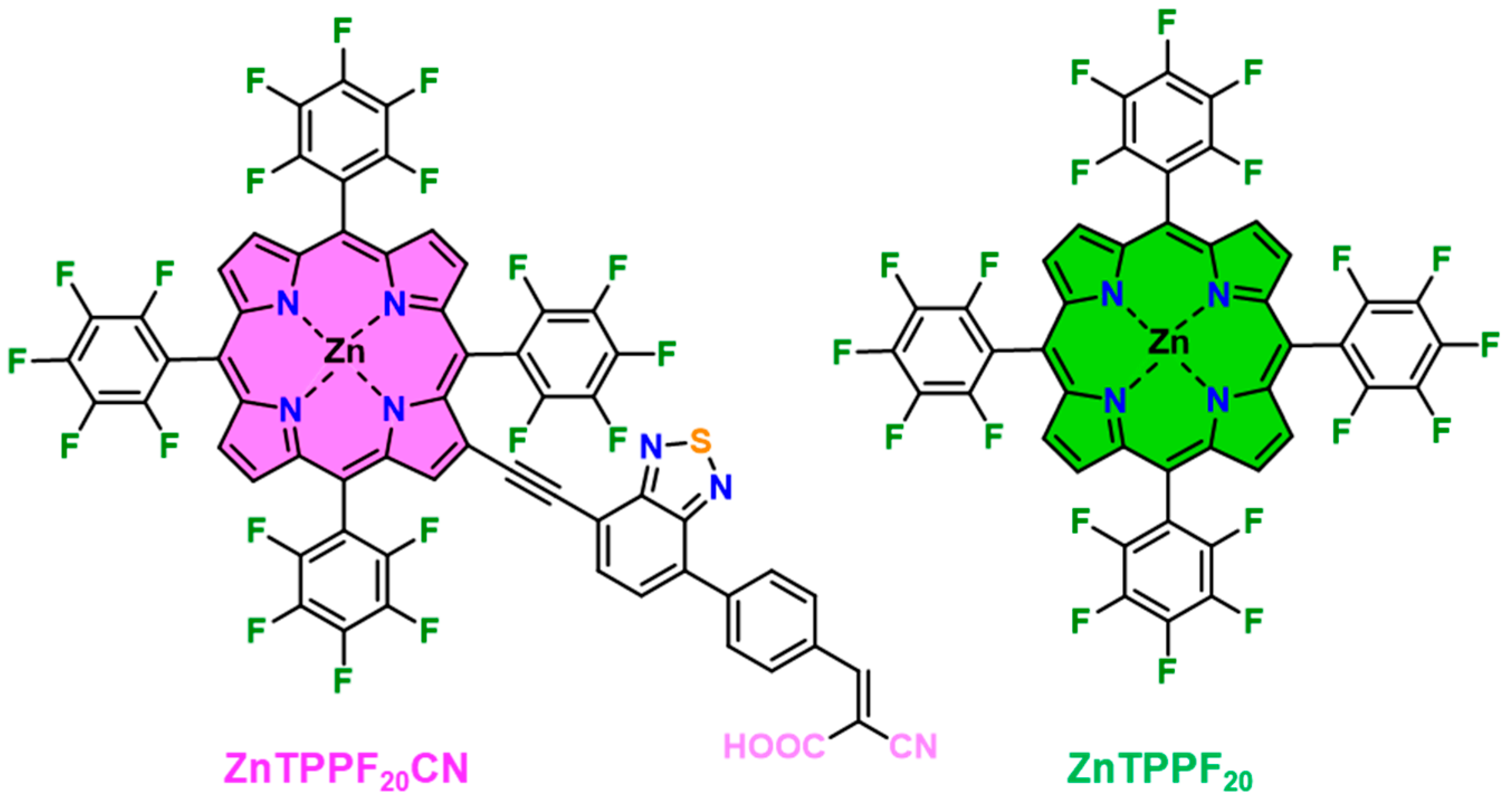

Chemisorption vs. Physisorption in Perfluorinated Zn(II) Porphyrin–SnO2 Hybrids for Acetone Chemoresistive Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

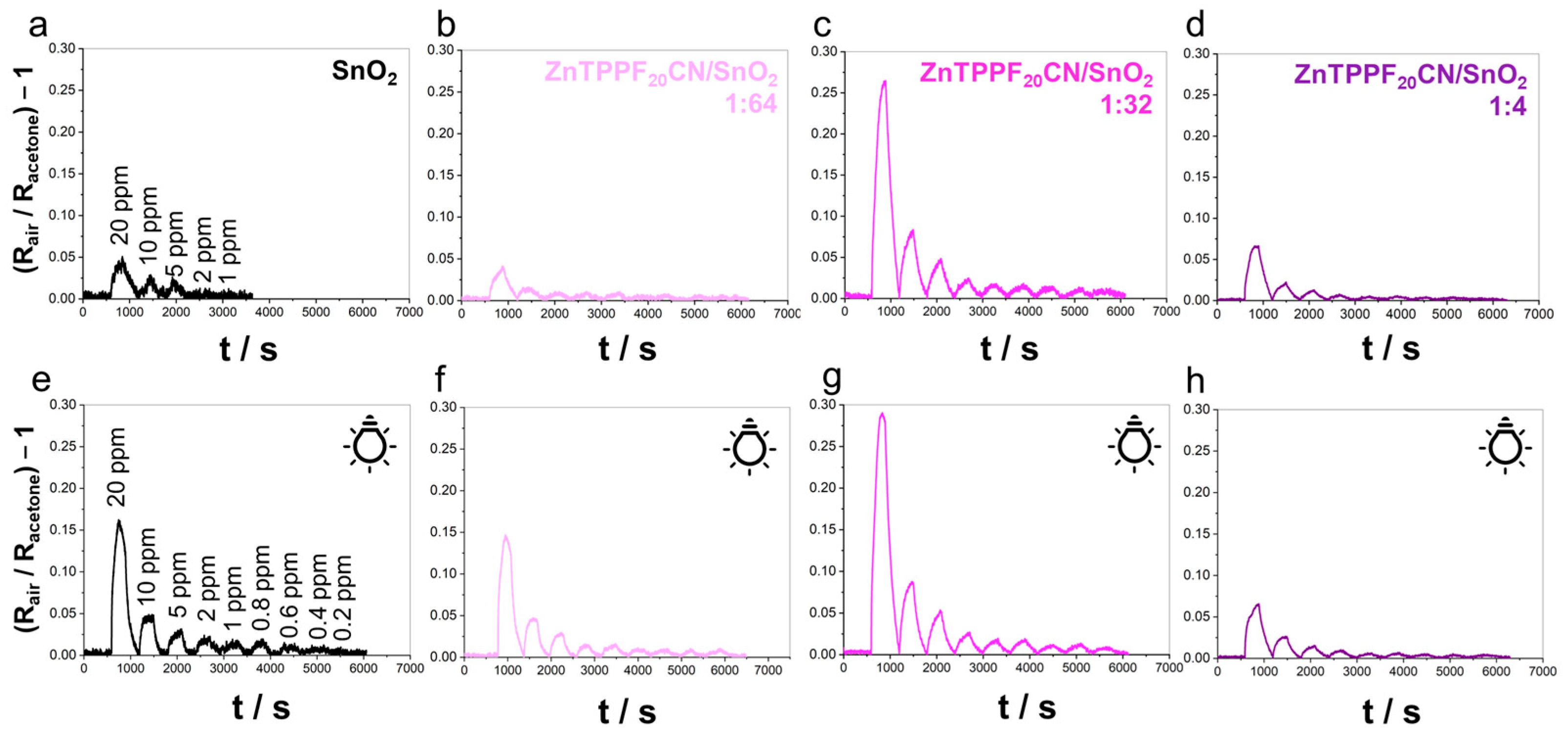

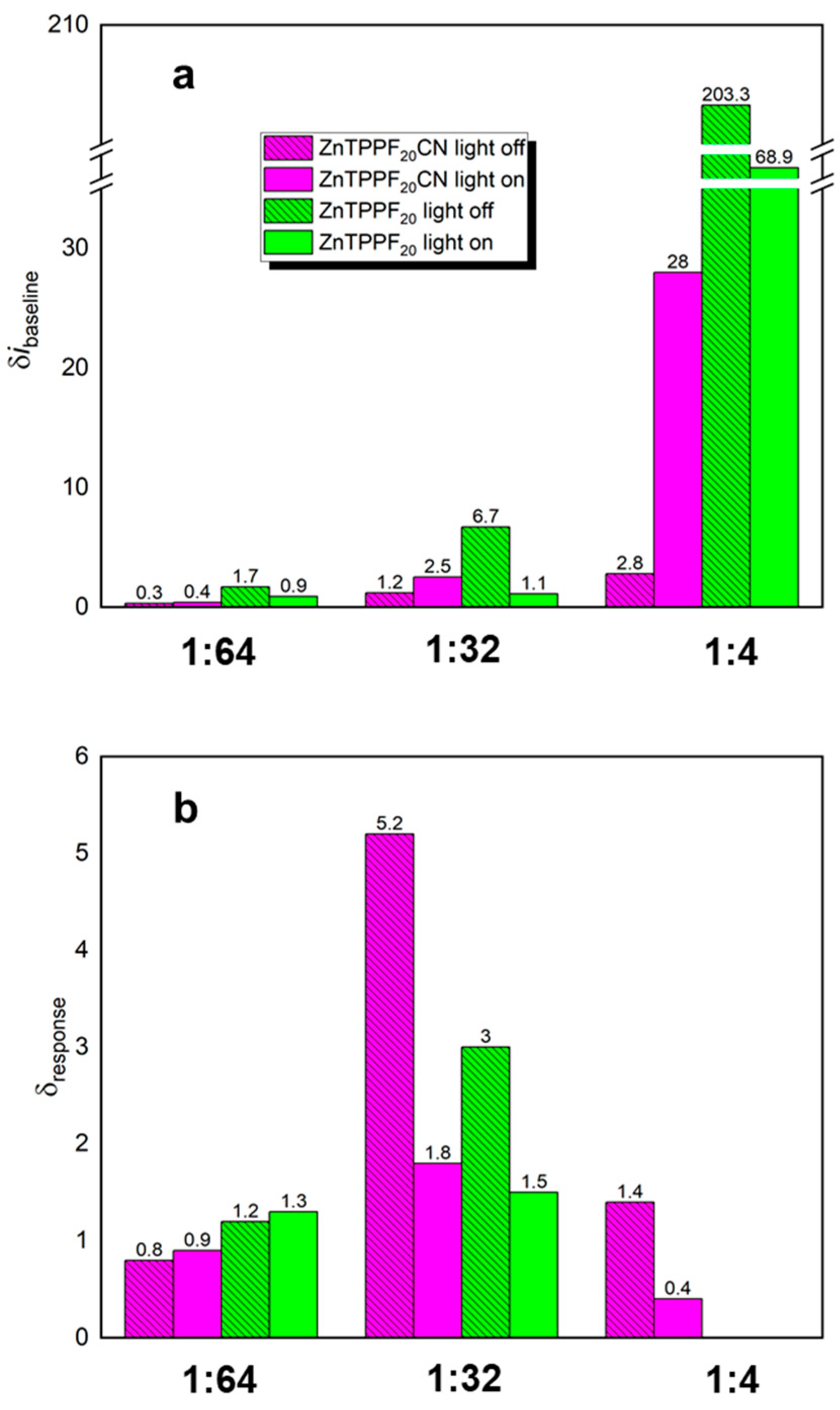

2.1. Acetone Sensing

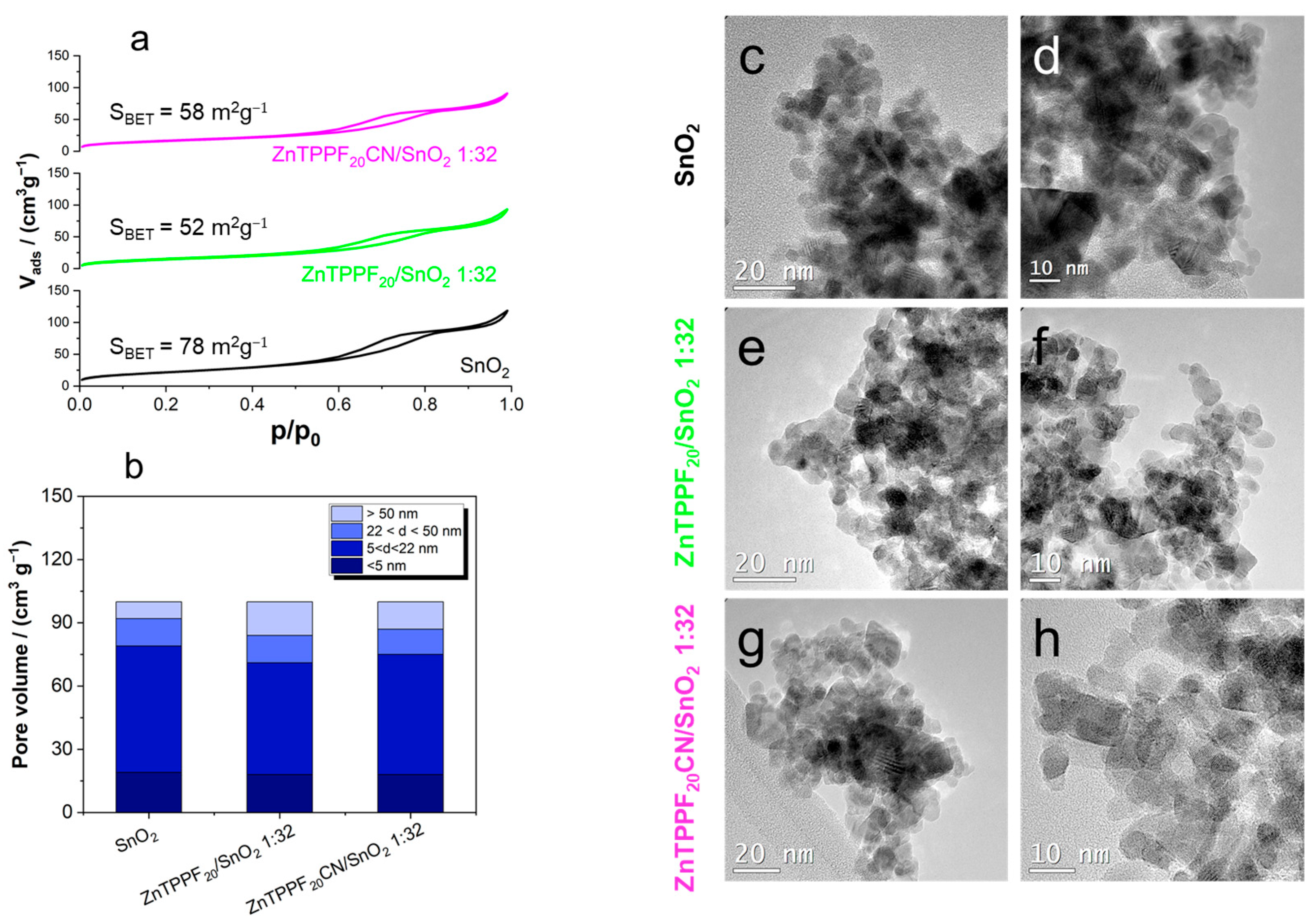

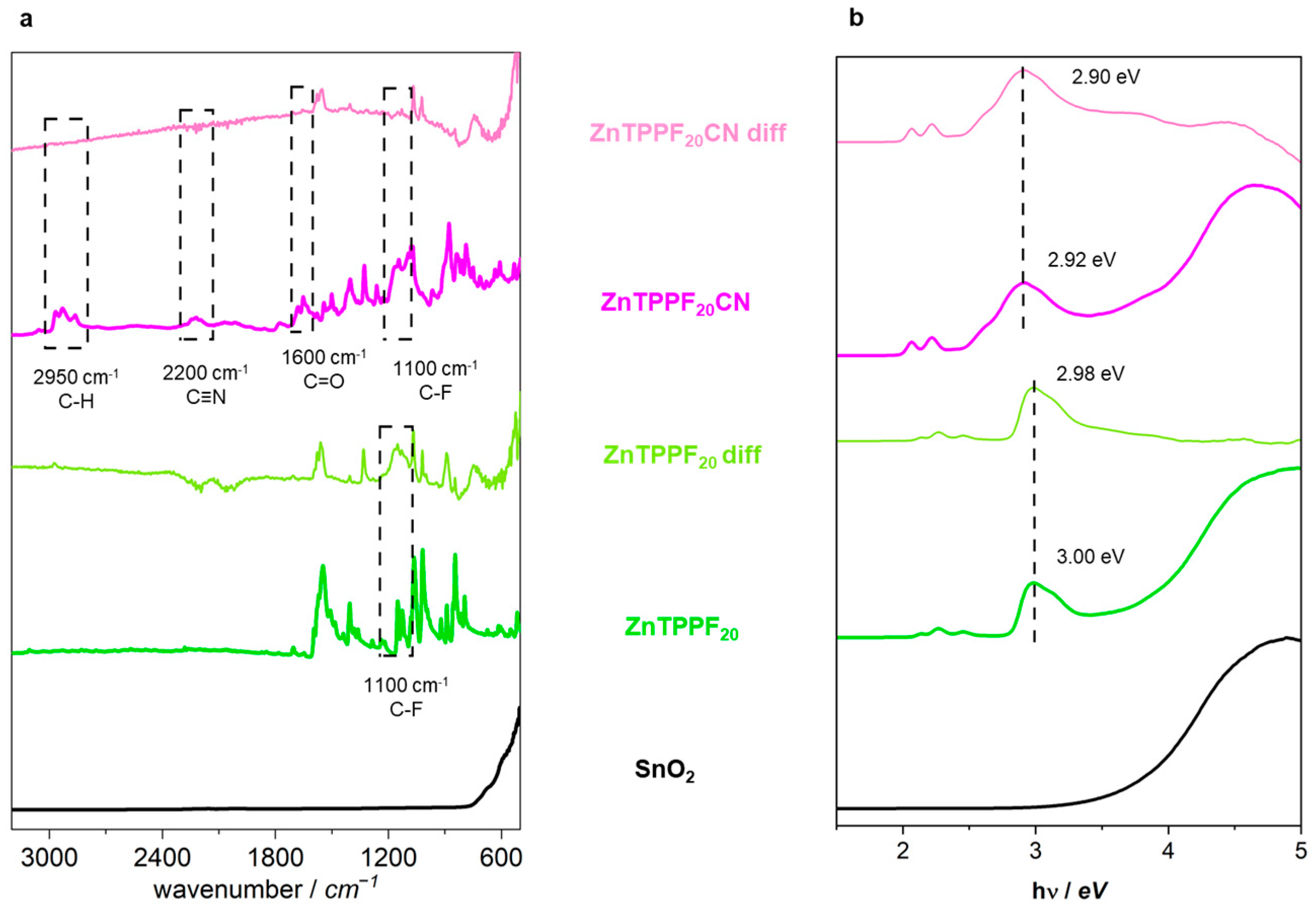

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of the 1:32 ZnTPPF20CN/SnO2 Composite

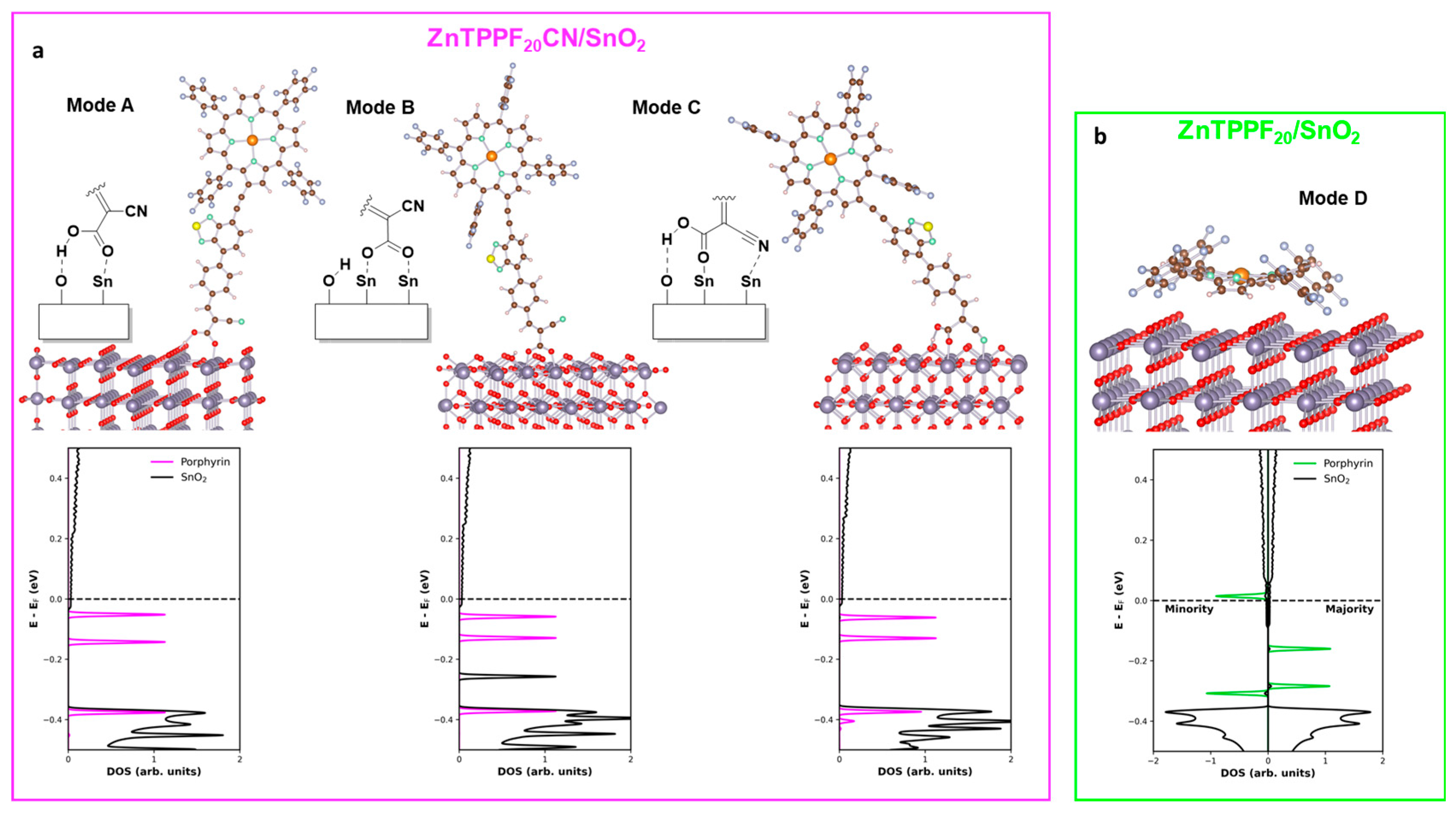

2.3. Ab Initio Calculations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis of ZnTPPF20CN, SnO2 and Hybrid Materials

4.2. Characterization of ZnTPPF20CN and of the 1:32 ZnTPPF20CN/SnO2 Composite

4.3. Preparation of the Electrodes

4.4. Computational Details

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banica, F.-G. Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barandun, G.; Gonzalez-Macia, L.; Lee, H.S.; Dincer, C.; Güder, F. Challenges and opportunities for printed electrical gas sensors. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 2804–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milone, A.; Monteduro, A.G.; Rizzato, S.; Leo, A.; Di Natale, C.; Kim, S.S.; Maruccio, G. Advances in materials and technologies for gas sensing from environmental and food monitoring to breath analysis. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2023, 7, 2200083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargoletti, E.; Cappelletti, G. Breakthroughs in the design of novel carbon-based metal oxides nanocomposites for VOCs gas sensing. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Li, R.; Meng, F.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, K.; Han, E. Approaches to enhancing gas sensing properties: A review. Sensors 2019, 19, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolesse, R.; Nardis, S.; Monti, D.; Stefanelli, M.; Di Natale, C. Porphyrinoids for chemical sensor applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 2517–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, N.J.; Kompalla, J.F.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Orthogonal gas sensor arrays by chemoresistive material design. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricoli, A.; Righettoni, M.; Teleki, A. Semiconductor gas sensors: Dry synthesis and application. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 7632–7659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, J.; Abegg, S.; Pratsinis, S.E.; Güntner, A.T. Highly selective detection of methanol over ethanol by a handheld gas sensor. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Zeng, W. Room-temperature gas sensing of ZnO-based gas sensor: A review. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 267, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Choi, P.G.; Masuda, Y. Large-lateral-area SnO2 nanosheets with a loose structure for high-performance acetone sensor at the ppt level. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 455, 131592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargoletti, E.; Tricoli, A.; Pifferi, V.; Orsini, S.; Longhi, M.; Guglielmi, V.; Cerrato, G.; Falciola, L.; Derudi, M.; Cappelletti, G. An electrochemical outlook upon the gaseous ethanol sensing by graphene oxide-SnO2 hybrid materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 483, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Khan, K.; Zou, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. Recent advances in emerging 2D material-based gas sensors: Potential in disease diagnosis. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1901329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Zheng, W.; Wang, H.; Li, H.-Y.; Yu, M.-H.; Chang, Z.; Bu, X.-H.; Liu, H. Facile engineering of metal–organic framework derived SnO2-ZnO composite based gas sensor toward superior acetone sensing performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Choi, S.-J.; Jang, J.-S.; Kim, N.-H.; Hakim, M.; Tuller, H.L.; Kim, I.-D. Mesoporous WO3 nanofibers with protein-templated nanoscale catalysts for detection of trace biomarkers in exhaled breath. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 5891–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Sun, J.; Song, P.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Q. Synthesis of reduced graphene oxide/SnO2 nanosheets/Au nanoparticles ternary composites with enhanced formaldehyde sensing performance. Phys. E Low-Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 2020, 118, 113953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammu, S.; Dua, V.; Agnihotra, S.R.; Surwade, S.P.; Phulgirkar, A.; Patel, S.; Manohar, S.K. Flexible, all-organic chemiresistor for detecting chemically aggressive vapors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4553–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.; Sengupta, S.K.; Baruch, M.F.; Granz, C.D.; Ammu, S.; Manohar, S.K.; Whitten, J.E. A hybrid chemiresistive sensor system for the detection of organic vapors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2011, 156, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.M. Porphyrins and Metalloporphyrins; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 1975; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Gouterman, M. Spectra of porphyrins. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1961, 6, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouterman, M.; Wagnière, G.H.; Snyder, L.C. Spectra of porphyrins: Part II. Four orbital model. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1963, 11, 108–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, J.; Maurin, A.; Robert, M. Molecular catalysis of the electrochemical and photochemical reduction of CO2 with Fe and Co metal based complexes. Recent advances. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017, 334, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limosani, F.; Remita, H.; Tagliatesta, P.; Bauer, E.M.; Leoni, A.; Carbone, M. Functionalization of Gold Nanoparticles with Ru-Porphyrin and Their Selectivity in the Oligomerization of Alkynes. Materials 2022, 15, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, G.; Pizzotti, M.; Righetto, S.; Forni, A.; Tessore, F. Electric-Field-Induced Second Harmonic Generation Nonlinear Optic Response of A4 β-Pyrrolic-Substituted ZnII Porphyrins: When Cubic Contributions Cannot Be Neglected. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 7561–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limosani, F.; Tessore, F.; Di Carlo, G.; Forni, A.; Tagliatesta, P. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Porphyrin, Fullerene and Ferrocene Hybrid Materials. Materials 2021, 14, 4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limosani, F.; Tessore, F.; Forni, A.; Lembo, A.; Di Carlo, G.; Albanese, C.; Bellucci, S.; Tagliatesta, P. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Zn (II) Porphyrin, Graphene Nanoplates, and Ferrocene Hybrid Materials. Materials 2023, 16, 5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covezzi, A.; Orbelli Biroli, A.; Tessore, F.; Forni, A.; Marinotto, D.; Biagini, P.; Di Carlo, G.; Pizzotti, M. 4D–π–1A type β-substituted Zn II-porphyrins: Ideal green sensitizers for building-integrated photovoltaics. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 12642–12645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathew, S.; Yella, A.; Gao, P.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Curchod, B.F.E.; Ashari-Astani, N.; Tavernelli, I.; Rothlisberger, U.; Nazeeruddin, K.; Grätzel, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells with 13% efficiency achieved through the molecular engineering of porphyrin sensitizers. Nat. Chem. 2014, 6, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, G.; Caramori, S.; Trifiletti, V.; Giannuzzi, R.; De Marco, L.; Pizzotti, M.; Orbelli Biroli, A.; Tessore, F.; Argazzi, R.; Bignozzi, C.A. Influence of Porphyrinic Structure on Electron Transfer Processes at the Electrolyte/Dye/TiO2 Interface in PSSCs: A Comparison between meso Push–Pull and β-Pyrrolic Architectures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 15841–15852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Carlo, G.; Albanese, C.; Molinari, A.; Carli, S.; Minguzzi, R.A.A.; Tessore, F.; Marchini, E.; Caramori, S. Perfluorinated Zinc Porphyrin Sensitized Photoelectrosynthetic Cells for Enhanced TEMPO-Mediated Benzyl Alcohol Oxidation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 14864–14882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbelli Biroli, A.; Tessore, F.; Di Carlo, G.; Pizzotti, M.; Benazzi, E.; Gentile, F.; Berardi, S.; Bignozzi, C.A.; Argazzi, R.; Natali, M.; et al. Fluorinated ZnII porphyrins for dye-sensitized aqueous photoelectrosynthetic cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 32895–32908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkova, G.; Zav’yalov, S.A.; Glagolev, N.N.; Solov’eva, A.B. The influence of ZnO-sensor modification by porphyrins on to the character of sensor response to volatile Organic compounds. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 84, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardis, S.; Monti, D.; Di Natale, C.; D’Amico, A.; Siciliano, P.; Forleo, A.; Epifani, M.; Taurino, A.; Rella, R.; Paolesse, R. Preparation and characterization of cobalt porphyrin modified tin dioxide films for sensor applications. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 103, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessore, F.; Pargoletti, E.; Di Carlo, G.; Albanese, C.; Soave, R.; Trioni, M.I.; Marelli, F.; Cappelletti, G. How the Interplay between SnO2 and Zn(II) Porphyrins Impacts on the Electronic Features of Gaseous Acetone Chemiresistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 41086–41098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pargoletti, E.; Hossain, U.H.; Di Bernardo, I.; Chen, H.; Tran-Phu, T.; Chiarello, G.L.; Lipton-Duffin, J.; Pifferi, V.; Tricoli, A.; Cappelletti, G. Engineering of SnO2–Graphene Oxide Nanoheterojunctions for Selective Room-Temperature Chemical Sensing and Optoelectronic Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 39549–39560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucher, L.J.; Katz, J.J. The Infared Spectra of Metalloporphyrins (4000–160 cm−1). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, S.; Caramori, S.; Benazzi, E.; Zabini, N.; Niorettini, A.; Orbelli Biroli, A.; Pizzotti, M.; Tessore, F.; Di Carlo, G. Electronic Properties of Electron-Deficient Zn(II) Porphyrins for HBr Splitting. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, H.; Schifano, V.; Colciago, G.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Ferretti, A.M.; Di Carlo, G.; Dozzi, M.V.; Vago, R.; Tessore, F.; Maggioni, D. Halloysite nanotubes as a vector for hydrophobic perfluorinated porphyrin-based photosensitizers for singlet oxygen generation. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 18935–18947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäki-Jaskari, M.A.; Rantala, T.T. Band structure and optical parameters of the SnO2 (110) surface. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 075407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, L.F.; Beifuss, U. The knoevenagel reaction. Compr. Org. Synth. 1992, 2, 341–394. [Google Scholar]

- Maleki, F.; Pacchioni, G. A DFT study of formic acid decomposition on the stoichiometric SnO2 surface as a function of iso-valent doping. Surf. Sci. 2022, 718, 122009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargoletti, E.; Hossain, U.H.; Di Bernardo, I.; Chen, H.; Tran-Phu, T.; Lipton-Duffin, J.; Cappelletti, G.; Tricoli, A. Room-temperature photodetectors and VOC sensors based on graphene oxide–ZnO nano-heterojunctions. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 22932–22945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Americo, S.; Pargoletti, E.; Soave, R.; Cargnoni, F.; Trioni, M.I.; Chiarello, G.L.; Cerrato, G.; Cappelletti, G. Unveiling the acetone sensing mechanism by WO3 chemiresistors through a joint theory-experiment approach. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 371, 137611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, J.M.; Artacho, E.; Gale, J.D.; García, A.; Junquera, J.; Ordejón, P.; Sánchez-Portal, D. The SIESTA method for ab initio order-Nmaterials simulation. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2002, 14, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W.; Bader, R.F. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Otero-de-la-Roza, A.; Johnson, E.R.; Luaña, V. Critic2: A program for real-space analysis of quantum chemical interactions in solids. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2014, 185, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, C.A.; Perfecto, T.M.; Volanti, D.P. Impact of reduced graphene oxide on the ethanol sensing performance of hollow SnO2 nanoparticles under humid atmosphere. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 244, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righettoni, M.; Tricoli, A.; Pratsinis, S.E. Si:WO3 Sensors for Highly Selective Detection of Acetone for Easy Diagnosis of Diabetes by Breath Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 3581–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, Y. Ultrasensitive and low detection limit of acetone gas sensor based on ZnO/SnO2 thick films. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 35958–35965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, X.; Xie, N.; Chen, F.; Wang, T.; Guo, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ma, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; et al. Superior acetone gas sensor based on electrospun SnO2 nanofibers by Rh doping. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 256, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Xie, K.; Fang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y. Cocrystallization Enabled Spatial Self-Confinement Approach to Synthesize Crystalline Porous Metal Oxide Nanosheets for Gas Sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2022, 61, e202207816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecule | Mode | Adsorption Energy eV | Integrated Charge e− |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnTPPF20CN | A | −1.61 | 0.38 |

| B | −2.01 | 0.20 | |

| C | −1.87 | 0.24 | |

| ZnTPPF20 | D | −0.15 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minnucci, M.; Oregioni, S.; Pargoletti, E.; Di Carlo, G.; Tessore, F.; Chiarello, G.L.; Martinazzo, R.; Trioni, M.I.; Cappelletti, G. Chemisorption vs. Physisorption in Perfluorinated Zn(II) Porphyrin–SnO2 Hybrids for Acetone Chemoresistive Detection. Molecules 2025, 30, 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244749

Minnucci M, Oregioni S, Pargoletti E, Di Carlo G, Tessore F, Chiarello GL, Martinazzo R, Trioni MI, Cappelletti G. Chemisorption vs. Physisorption in Perfluorinated Zn(II) Porphyrin–SnO2 Hybrids for Acetone Chemoresistive Detection. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244749

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinnucci, Manuel, Sara Oregioni, Eleonora Pargoletti, Gabriele Di Carlo, Francesca Tessore, Gian Luca Chiarello, Rocco Martinazzo, Mario Italo Trioni, and Giuseppe Cappelletti. 2025. "Chemisorption vs. Physisorption in Perfluorinated Zn(II) Porphyrin–SnO2 Hybrids for Acetone Chemoresistive Detection" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244749

APA StyleMinnucci, M., Oregioni, S., Pargoletti, E., Di Carlo, G., Tessore, F., Chiarello, G. L., Martinazzo, R., Trioni, M. I., & Cappelletti, G. (2025). Chemisorption vs. Physisorption in Perfluorinated Zn(II) Porphyrin–SnO2 Hybrids for Acetone Chemoresistive Detection. Molecules, 30(24), 4749. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244749