Co-Reactant Engineering for Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

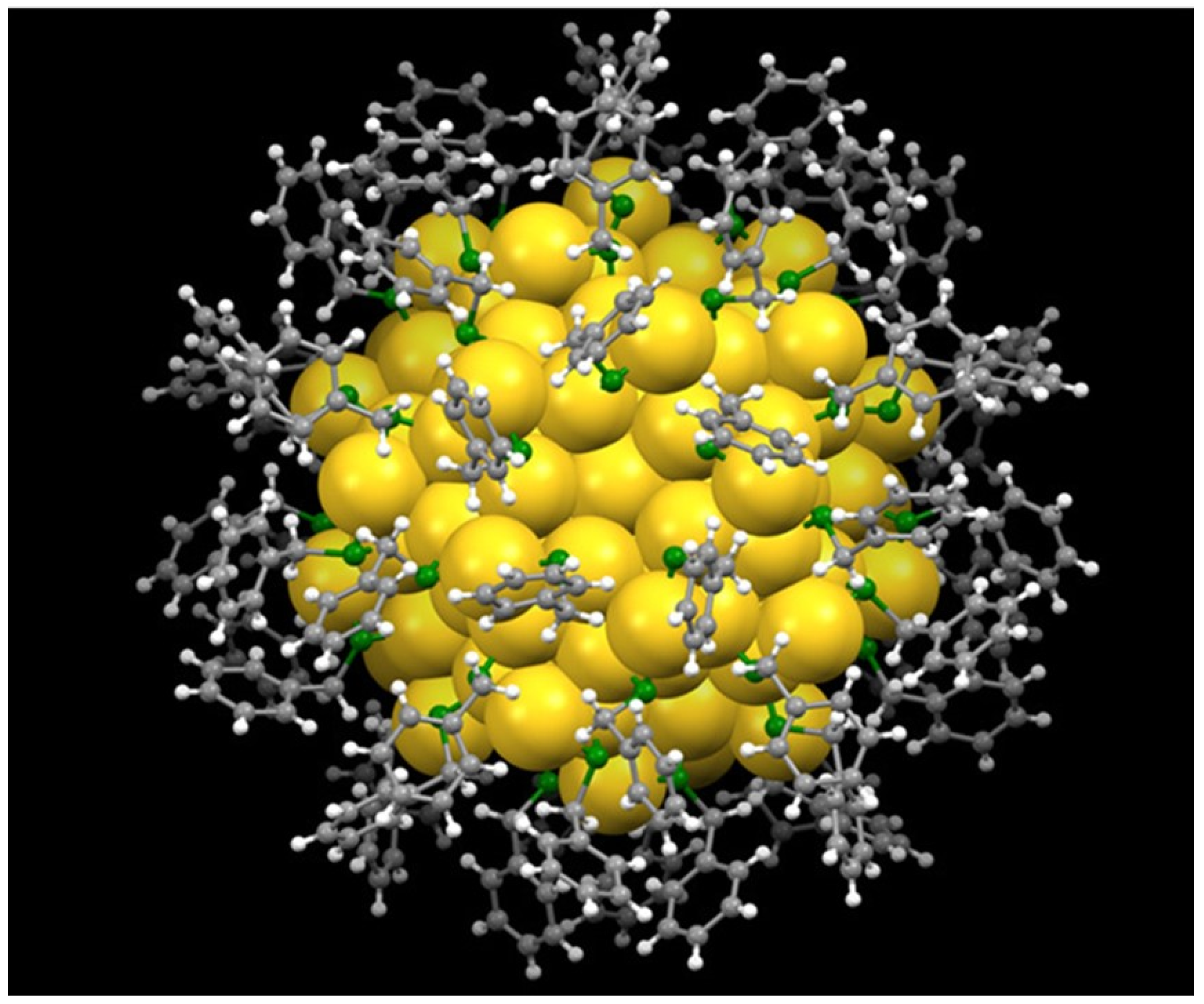

2. Fundamentals of Au NCs-Based ECL

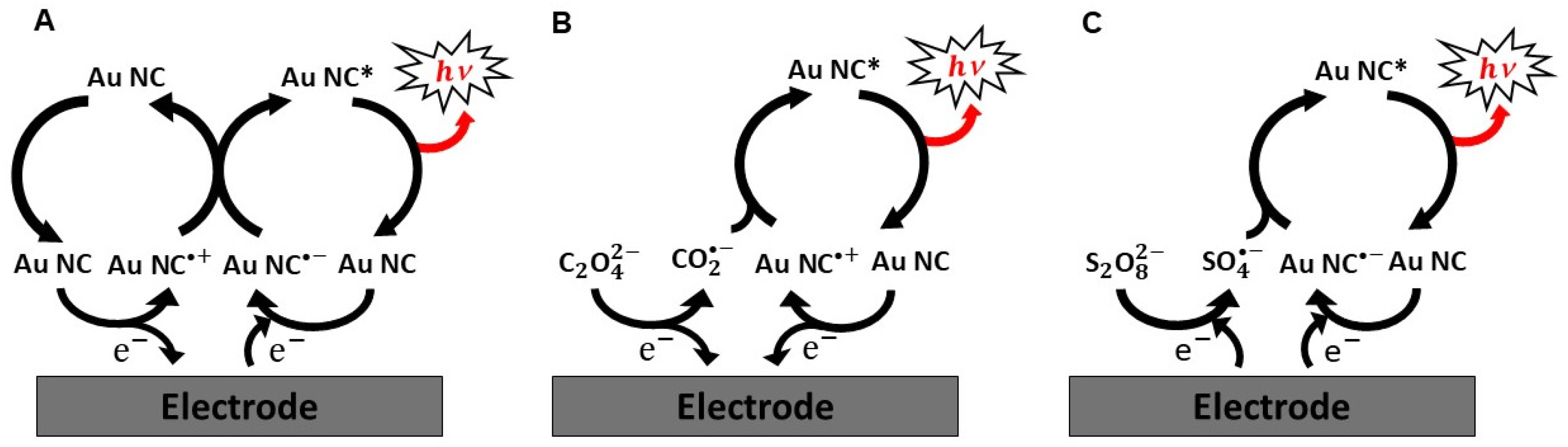

2.1. ECL Mechanisms of Au NCs

2.2. Co-Reactants in Au NCs-Based ECL Systems

3. Co-Reactants Engineering Strategies

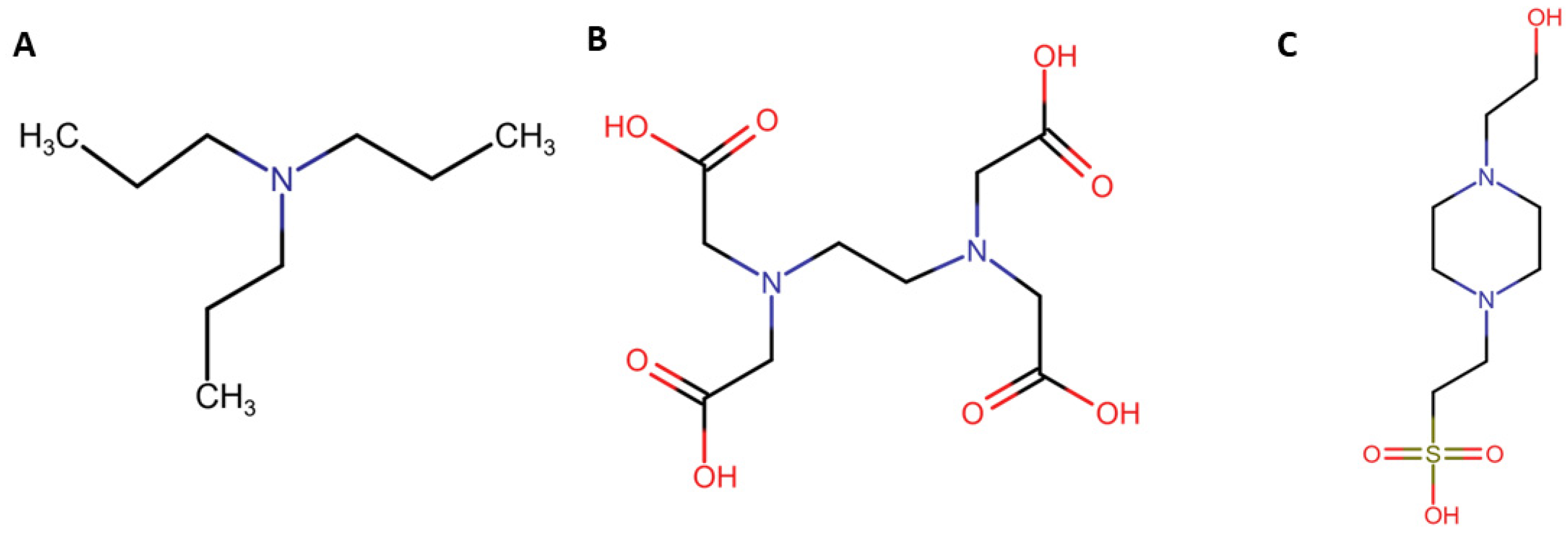

3.1. Design of New Co-Reactant Molecules

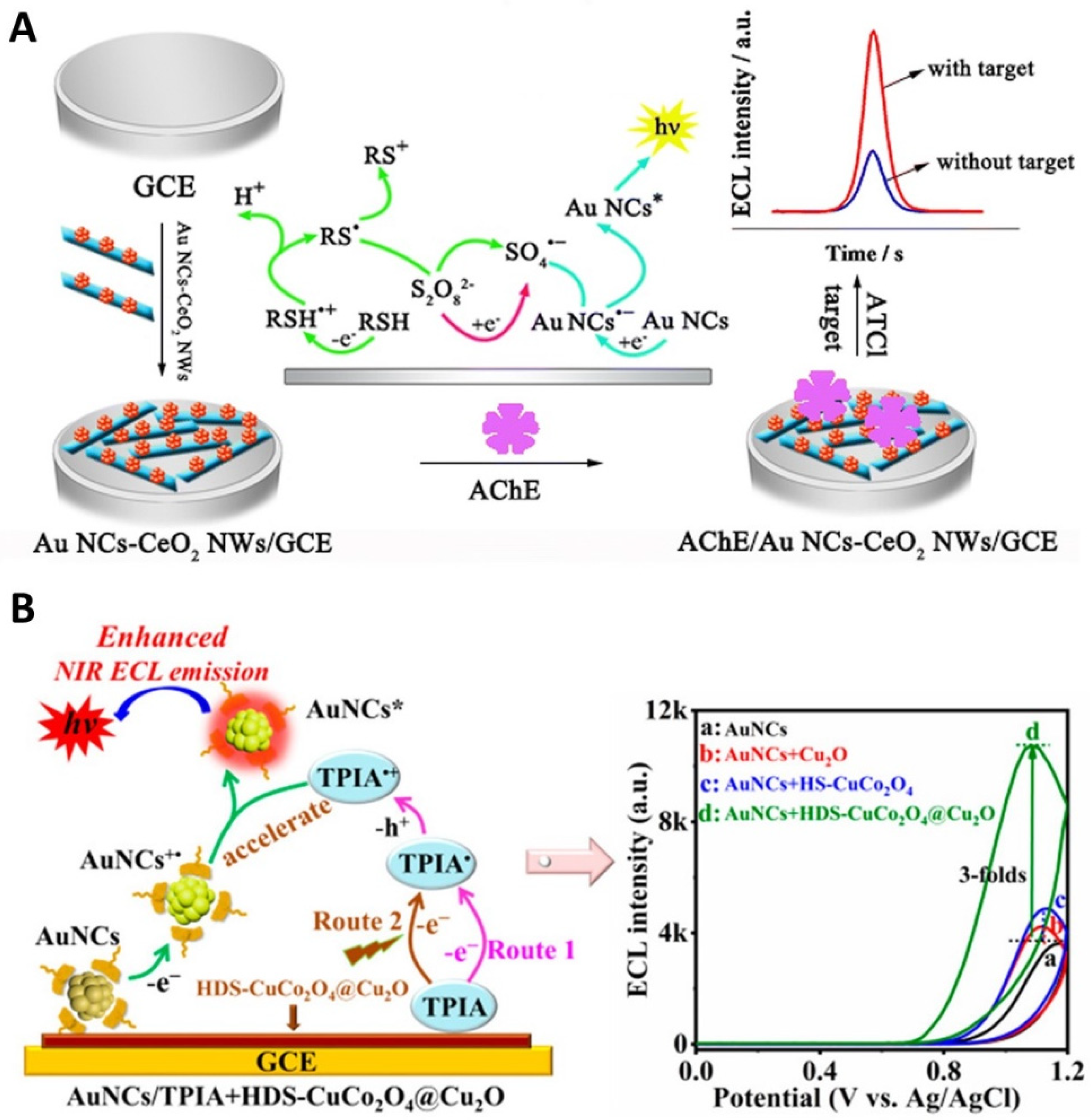

3.2. Use of Co-Reaction Accelerator

3.3. Integration of Co-Reactant with Au NCs

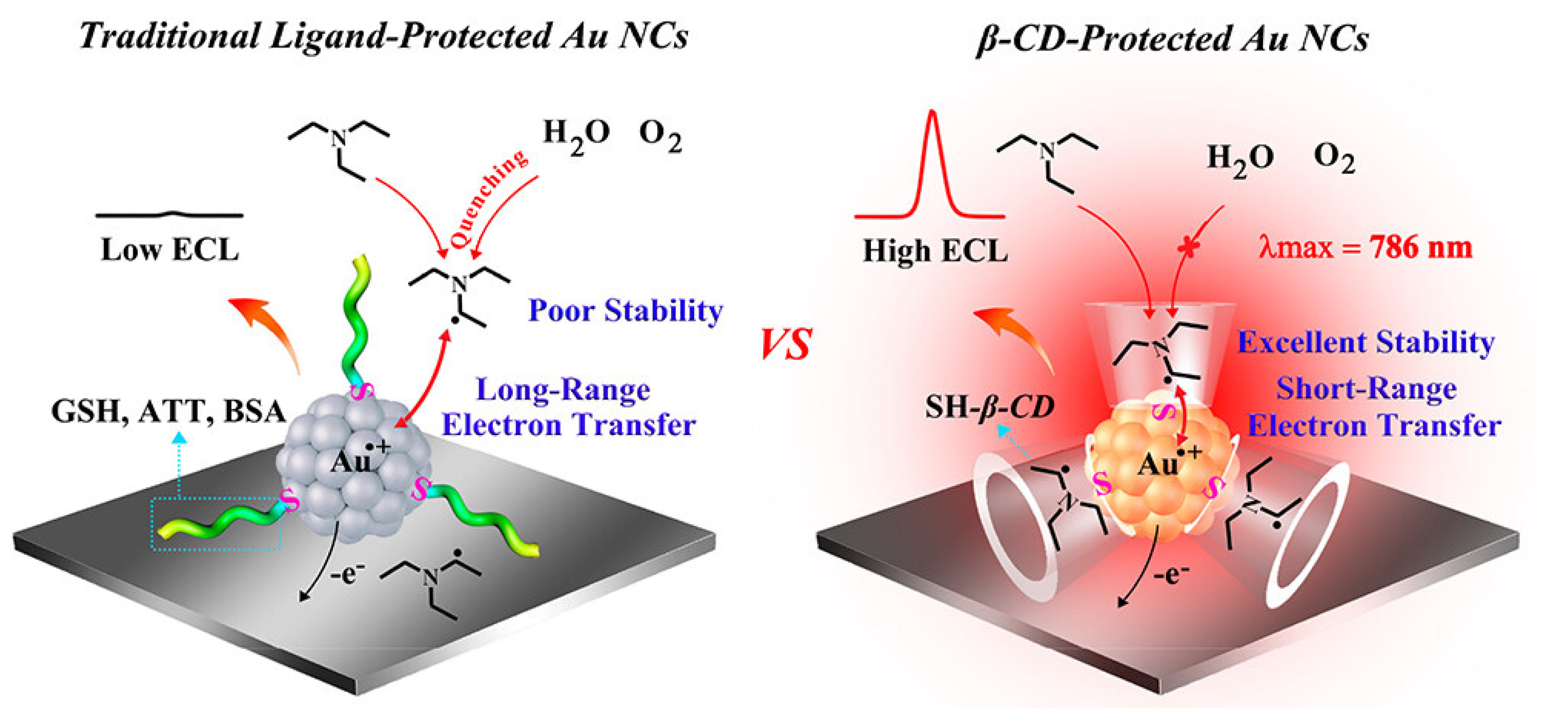

3.4. Host–Guest Encapsulation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yau, S.H.; Varnavski, O.; Goodson, T. An Ultrafast Look at Au Nanoclusters. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Fang, B.; Peng, J.; Deng, S.; Hu, L.; Lai, W. Luminescent Gold Nanoclusters from Synthesis to Sensing: A Comprehensive Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 158294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-J.; Alkan, F.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, D.; Nawaz, T.; Guo, J.; Luo, X.; He, J. Atomically Precise Gold Nanoclusters at the Molecular-to-Metallic Transition with Intrinsic Chirality from Surface Layers. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Looij, S.M.; Hebels, E.R.; Viola, M.; Hembury, M.; Oliveira, S.; Vermonden, T. Gold Nanoclusters: Imaging, Therapy, and Theranostic Roles in Biomedical Applications. Bioconjug. Chem. 2022, 33, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Hou, P.; Wei, J.; Li, B.; Gao, A.; Yuan, Z. Recent Advances in Gold Nanocluster-Based Biosensing and Therapy: A Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qian, H.; Jin, R. Catalysis Opportunities of Atomically Precise Gold Nanoclusters. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa Farkhani, S.; Dehghankelishadi, P.; Refaat, A.; Veerasikku Gopal, D.; Cifuentes-Rius, A.; Voelcker, N.H. Tailoring Gold Nanocluster Properties for Biomedical Applications: From Sensing to Bioimaging and Theranostics. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 142, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, D.; Roy, S.; Gaur, R. Application of Nanoclusters in Environmental and Biological Fields. In Handbook of Green and Sustainable Nanotechnology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.-D. Gold Nanoclusters for Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2023, 3, 2300082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Kim, T.W.; Kang, Y.; Ju, Y.; Ryu, J.; Kong, H.; Jang, Y.-S.; Oh, D.E.; Jang, S.J.; Cho, H.; et al. Targeted Drug Delivery Nanocarriers Based on Hyaluronic Acid-Decorated Dendrimer Encapsulating Gold Nanoparticles for Ovarian Cancer Therapy. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Choi, H.S.; Go, B.R.; Kim, J. Modification of a Glassy Carbon Surface with Amine-Terminated Dendrimers and Its Application to Electrocatalytic Hydrazine Oxidation. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 788–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, R. Quantum Sized, Thiolate-Protected Gold Nanoclusters. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawa, M.I.; Lai, J.; Xu, G. Gold Nanoclusters: Synthetic Strategies and Recent Advances in Fluorescent Sensing. Mater. Today Nano 2018, 3, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Zhu, M.; Wu, Z.; Jin, R. Quantum Sized Gold Nanoclusters with Atomic Precision. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Sohn, S.H.; Han, N.S.; Park, S.M.; Kim, J.; Song, J.K. Blue Luminescence of Dendrimer-Encapsulated Gold Nanoclusters. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 2917–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, M.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Q. Synthesis, Optical Properties and Applications of Ultra-Small Luminescent Gold Nanoclusters. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 57, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Xia, N.; Liao, L.; Zhu, M.; Jin, F.; Jin, R.; Wu, Z. Unraveling the Long-Pursued Au144 Structure by x-Ray Crystallography. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat7259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, M.M. Electrochemiluminescence (ECL). Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 3003–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, X.; Xing, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhu, J.-J. A Close Look at Mechanism, Application, and Opportunities of Electrochemiluminescence Microscopy. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2023, 1, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesari, M.; Ding, Z. Review—Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence: Light Years Ahead. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, H3116–H3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepomnyashchii, A.B.; Bard, A.J. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of BODIPY Dyes. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 1844–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence and Its Biorelated Applications. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2506–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bard, A.J.; Ding, Z.; Myung, N. Electrochemistry and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Semiconductor Nanocrystals in Solutions and in Films. In Semiconductor Nanocrystals and Silicate Nanoparticles; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 1–57.

- Allen, J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence; Bard, A.J., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780203027011. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, B. Co-reactant Catalysts for Enhancing Electrochemiluminescence Bioassays. Anal. Sens. 2025, 5, 2500063. [Google Scholar]

- Schluederberg, C.G. Actinic Electrolysis. J. Phys. Chem. 1908, 12, 574–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanut, A.; Fiorani, A.; Canola, S.; Saito, T.; Ziebart, N.; Rapino, S.; Rebeccani, S.; Barbon, A.; Irie, T.; Josel, H.-P.; et al. Insights into the Mechanism of Coreactant Electrochemiluminescence Facilitating Enhanced Bioanalytical Performance. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Gao, W.; Du, F.; Yuan, F.; Yu, J.; Guan, Y.; Sojic, N.; Xu, G. Rational Design of Electrochemiluminescent Devices. Acc. Chem. Res. 2021, 54, 2936–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, T.; Lim, S.Y.; Kim, J. Flexible and Dynamic Light-Guided Electrochemiluminescence for Spatiotemporal Imaging of Photoelectrochemical Processes on Hematite. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 11146–11154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Hussain, A.; Zholudov, Y.T.; Snizhko, D.V.; Sojic, N.; Xu, G. Self-Powered Electrochemiluminescence for Imaging the Corrosion of Protective Coating of Metal and Quantitative Analysis. Angew. Chem. 2024, 136, e202411764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-R.; Kim, J.; Oh, J.; Kim, J.; Hong, J.-I. Electrochemiluminescence of Dimethylaminonaphthalene-Oxazaborine Donor–Acceptor Luminophores. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 13058–13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Fan, C.; Zhuo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Xiong, C.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Multiparameter Analysis-Based Electrochemiluminescent Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Multiple Biomarker Proteins on a Single Interface. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4940–4948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadimisetty, K.; Malla, S.; Sardesai, N.P.; Joshi, A.A.; Faria, R.C.; Lee, N.H.; Rusling, J.F. Automated Multiplexed ECL Immunoarrays for Cancer Biomarker Proteins. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 4472–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.M.; Wen, R.X.; Zhou, J.; Chai, Y.Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. Silver Ions as Novel Coreaction Accelerator for Remarkably Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence in a PTCA-S2O82− System and Its Application in an Ultrasensitive Assay for Mercury Ions. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 6851–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, L.; Li, F.; Zhao, W.; Luo, L.; Bi, X.; Li, X.; You, T. An Ultra-High-Sensitivity Electrochemiluminescence Aptasensor for Pb2+ Detection Based on the Synergistic Signal-Amplification Strategy of Quencher Abscission and G-Quadruplex Generation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Tian, D.; Cui, H. Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor for the Assay of Small Molecule and Protein Based on Bifunctional Aptamer and Chemiluminescent Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 715, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Su, Y.; Ji, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, R.; Ding, L.; Chen, Y.; Song, D. Enhanced Detection of 4-Nitrophenol in Drinking Water: ECL Sensor Utilizing Velvet-like Graphitic Carbon Nitride and Molecular Imprinting. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Su, J.; Xiang, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y. In Situ Hybridization Chain Reaction Amplification for Universal and Highly Sensitive Electrochemiluminescent Detection of DNA. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 7750–7755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Xu, J.-J.; Chen, H.-Y. Distance-Dependent Quenching and Enhancing of Electrochemiluminescence from a CdS:Mn Nanocrystal Film by Au Nanoparticles for Highly Sensitive Detection of DNA. Chem. Commun. 2009, 8, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voci, S.; Goudeau, B.; Valenti, G.; Lesch, A.; Jović, M.; Rapino, S.; Paolucci, F.; Arbault, S.; Sojic, N. Surface-Confined Electrochemiluminescence Microscopy of Cell Membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14753–14760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.; Scarabino, S.; Goudeau, B.; Lesch, A.; Jović, M.; Villani, E.; Sentic, M.; Rapino, S.; Arbault, S.; Paolucci, F.; et al. Single Cell Electrochemiluminescence Imaging: From the Proof-of-Concept to Disposable Device-Based Analysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16830–16837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesari, M.; Ding, Z. A Grand Avenue to Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, J. Effect of Surface Ligand Density on Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence of Glutathione-Stabilized Au Nanoclusters. Electrochim. Acta 2024, 487, 144139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, J. Enhanced Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence of Au Nanoclusters Treated with Piperidine. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 147, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Kim, J. Post-Synthesis Modification of Photoluminescent and Electrochemiluminescent Au Nanoclusters with Dopamine. Nanomaterials 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Kim, J. Electrochemiluminescence of Glutathione-Stabilized Au Nanoclusters Fractionated by Gel Electrophoresis in Water. ChemElectroChem 2020, 7, 1092–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Jeong, S.; Song, J.K.; Kim, J. Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence from Orange Fluorescent Au Nanoclusters in Water. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 2838–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Yang, L.; Dong, X.; Zhou, L.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Cysteine Modification of Glutathione-Stabilized Au Nanoclusters to Red-Shift and Enhance the Electrochemiluminescence for Sensitive Bioanalysis. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, M.; Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Luo, L.; Ma, G.; Lv, W.; Li, L.; You, T. “Kill Two Birds with One Stone” Role of PTCA-COF: Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence of Au Nanoclusters via Radiative Transitions and Electrochemical Excitation for Sensitive Detection of Cadmium Ions. Sens. Actuators B 2025, 422, 136690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Mukherjee, S. Effects of Protecting Groups on Luminescent Metal Nanoclusters: Spectroscopic Signatures and Applications. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Su, C.; Lai, M.; Huang, Z.; Weng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Deng, H.; Chen, W.; Peng, H. Co-Reactant-Mediated Low-Potential Anodic Electrochemiluminescence Platform and Its Immunosensing Application. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 12500–12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.-M.; Wu, D.; Pan, M.-C.; Tao, X.-L.; Zeng, W.-J.; Gan, L.-Y.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. Dynamic Surface Reconstruction of Individual Gold Nanoclusters by Using a Co-Reactant Enables Color-Tunable Electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 3255–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xia, M.; Peng, D.; Zhao, Y.; Nie, Y.; Zhou, Y. Co-Reactive Ligand In Situ Engineered Gold Nanoclusters with Ultra-Bright Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence for Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Carboxylesterase Activity. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 2369–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.P.; Bard, A.J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence 73: Acid-Base Properties, Electrochemistry, and Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Neutral Red in Acetonitrile. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2004, 573, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Hou, X.; Xu, J.-J.; Chen, H.-Y. Electrochemically Generated versus Photoexcited Luminescence from Semiconductor Nanomaterials: Bridging the Valley between Two Worlds. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11027–11059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, G.; Fiorani, A.; Li, H.; Sojic, N.; Paolucci, F. Essential Role of Electrode Materials in Electrochemiluminescence Applications. ChemElectroChem 2016, 3, 1990–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Xu, G. Applications and Trends in Electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J.-J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Au Nanoclusters for the Detection of Dopamine. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesari, M.; Workentin, M.S.; Ding, Z. NIR Electrochemiluminescence from Au 25− Nanoclusters Facilitated by Highly Oxidizing and Reducing Co-Reactant Radicals. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 3814–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ding, Z. Electrochemiluminescence Biochemical Sensors. In World Scientific Series: From Biomaterials Towards Medical Devices; University of Houston: Houston, TX, USA, 2021; pp. 125–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hesari, M.; Ma, H.; Ding, Z. Monitoring Single Au38 Nanocluster Reactions via Electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14540–14545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Zhang, Q.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Shen, D.; Zou, G. Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay with Biocompatible Au Nanoclusters as Tags. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 7581–7587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Yu, S.; Yang, L.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence of Dual-Stabilizer-Capped Au Nanoclusters for Immunoassays. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 2657–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Zhang, B.; Gao, X.; Dong, S.; Wang, D.; Zou, G. A General Route for Chemiluminescence of N-Type Au Nanocrystals. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 8811–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Wei, C.; Zhu, C.; Deng, H.; Peng, H.; Xia, X.; Chen, W. Mechanistic Insight into a Novel Ultrasensitive Nicotine Assay Base on High-Efficiency Quenching of Gold Nanocluster Cathodic Electrochemiluminescence. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 11438–11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, W.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Ligand-Based Shielding Effect Induced Efficient Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence of Gold Nanoclusters and Its Sensing Application. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 6785–6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Instrumentation for Fluorescence Spectroscopy. In Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 25–61. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Huang, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Deng, H.; Chen, W.; Liu, J. Pre-oxidation of Gold Nanoclusters Results in a 66 % Anodic Electrochemiluminescence Yield and Drives Mechanistic Insights. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 11691–11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Huang, Z.; Deng, H.; Wu, W.; Huang, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Liu, J. Dual Enhancement of Gold Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence: Electrocatalytic Excitation and Aggregation-Induced Emission. Angew. Chem. 2020, 59, 9982–9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Yang, L.; Fan, D.; Kuang, X.; Sun, X.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Cobalt Ion Doping to Improve Electrochemiluminescence Emisssion of Gold Nanoclusters for Sensitive NIR Biosensing. Sens. Actuators B 2022, 367, 132034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesari, M.; Workentin, M.S.; Ding, Z. Thermodynamic and Kinetic Origins of Au250 Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 15116–15121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ma, H.; Padelford, J.W.; Qinchen, W.; Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhu, M.; Wang, G. Near Infrared Electrochemiluminescence of Rod-Shape 25-Atom AuAg Nanoclusters That Is Hundreds-Fold Stronger Than That of Ru(Bpy)3 Standard. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 9603–9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, B.; Fu, L.; Fu, K.; Zou, G. Efficient and Monochromatic Electrochemiluminescence of Aqueous-Soluble Au Nanoclusters via Host–Guest Recognition. Angew. Chem. 2019, 58, 6901–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sui, J.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, Z.; Bai, X. Design Strategies and Applications of Electrochemiluminescence from Metal Nanoclusters. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 1798–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Jian, M.; Deng, H.; Wang, W.; Huang, Z.; Huang, K.; Liu, A.; Chen, W. Valence States Effect on Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Gold Nanocluster. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 14929–14934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.-C.; Yang, Y.-T.; Guo, Y.-Z.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Liu, J.-L.; Yuan, R. Zn2+-Induced Gold Cluster Aggregation Enhanced Electrochemiluminescence for Ultrasensitive Detection of MicroRNA-21. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 5568–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Liu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zou, G. Low-Triggering-Potential Single-Color Electrochemiluminescence from Bovine Serum Albumin-Stabilized Unary Au Nanocrystals for Immunoassays. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 11688–11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wang, D.; Padelford, J.W.; Jiang, J.; Wang, G. Near-Infrared Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence from Aqueous Soluble Lipoic Acid Au Nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6380–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Luo, X.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Ternary Electrochemiluminescence Nanostructure of Au Nanoclusters as a Highly Efficient Signal Label for Ultrasensitive Detection of Cancer Biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 10024–10030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Ren, X.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Intramolecular Coreaction Accelerated Electrochemiluminescence of Polypeptide-Biomineralized Gold Nanoclusters for Targeted Detection of Biomarkers. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 9179–9187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhong, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R.; Wei, S. An Ultrasensitive Aptasensor Based on Self-Enhanced Au Nanoclusters as Highly Efficient Electrochemiluminescence Indicator and Multi-Site Landing DNA Walker as Signal Amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 130, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Lai, M.; Wang, H.; Weng, Z.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Sun, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, W. Energy Level Engineering in Gold Nanoclusters for Exceptionally Bright NIR Electrochemiluminescence at a Low Trigger Potential. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 11106–11112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Padelford, J.W.; Ma, H.; Gubitosi-Raspino, M.F.; Wang, G. Near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence from Au Nanoclusters Enhanced by EDTA and Modulated by Ions. ChemElectroChem 2017, 4, 1697–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ma, H.; Padelford, J.W.; Lobo, E.; Tran, M.T.; Zhao, F.; Fang, N.; Wang, G. Metal Ions-Modulated near-Infrared Electrochemiluminescence from Au Nanoclusters Enhanced by 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1-Piperazineethanesulfonic Acid at Physiological PH. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 282, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kuang, K.; Jing, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, S.; Zhu, M. Progress in Electrochemiluminescence of Metal Nanoclusters. Chem. Phys. Rev. 2024, 5, 041310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.K.; Jeon, S.-H.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Shim, B.-J.; Nam, K.; Köcher, S.S.; Lee, H.; Woo, H.-K.; Park, J.H.; et al. Discovery of a New Coreactant for Highly Efficient and Reliable Electrochemiluminescence. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2025, 6, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, W.; Choi, J.-P.; Bard, A.J. Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence 69: The Tris(2,2′-Bipyridine)Ruthenium(II), (Ru(Bpy)32+)/Tri-n-Propylamine (TPrA) System Revisited A New Route Involving TPrA•+ Cation Radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14478–14485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wei, J.; Chi, Y.; Zhou, S. Tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)Ruthenium(II)-Nanomaterial Co-Reactant Electrochemiluminescence. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 3878–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badocco, D.; Zanon, F.; Pastore, P. Use of Ru(Bpy)32+/Tertiary Aliphatic Amine System Fast Potential Pulses Electrochemiluminescence at Ultramicroelectrodes Coupled to Electrochemical Data for Evaluating E° of Amine Redox Couples. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 6442–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, P.; Badocco, D.; Zanon, F. Influence of Nature, Concentration and PH of Buffer Acid–Base System on Rate Determining Step of the Electrochemiluminescence of Ru(Bpy)32+ with Tertiary Aliphatic Amines. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 5394–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliszar, S. Charge Distribution and Chemical Effects in Saturated Hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972, 94, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Su, C.; Yang, Y.; Weng, Z.; Zhuang, Q.; Hong, G.; Peng, H.; Chen, W. Clinical Evaluation of the HER2 Extracellular Domain in Breast Cancer Patients by Herceptin-Encapsulated Gold Nanocluster Probe-Based Electrochemiluminescence Immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Advances in Electrochemiluminescence Co-Reaction Accelerator and Its Analytical Applications. Anal. BioAnal. Chem. 2021, 413, 4119–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Wei, D.; Yan, T.; Ju, H.; Du, B.; Wei, Q. Cobalt-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks as Co-Reaction Accelerator for Enhancing Electrochemiluminescence Behavior of N-(Aminobutyl)-N-(Ethylisoluminol) and Ultrasensitive Immunosensing of Amyloid-β Protein. Sens. Actuators B 2019, 291, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.-N.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chai, Y.-Q. New Signal Amplification Strategy Using Semicarbazide as Co-Reaction Accelerator for Highly Sensitive Electrochemiluminescent Aptasensor Construction. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 11389–11397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-F.; Liu, J.-L.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, R. Three-Dimensional Cadmium Telluride Quantum Dots–DNA Nanoreticulation as a Highly Efficient Electrochemiluminescent Emitter for Ultrasensitive Detection of MicroRNA from Cancer Cells. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 7765–7773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. A Sensitive Electrochemiluminescent Aptasensor Based on Perylene Derivatives as a Novel Co-Reaction Accelerator for Signal Amplification. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 85, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Gu, W.; Zhu, C. Recent Advances in Co-Reaction Accelerators for Sensitive Electrochemiluminescence Analysis. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 10989–10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Highly Efficient Electrochemiluminescent Silver Nanoclusters/Titanium Oxide Nanomaterials as a Signal Probe for Ferrocene-Driven Light Switch Bioanalysis. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 3732–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Yu, Y.-Q.; Peng, L.-Z.; Lei, Y.-M.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhuo, Y. Strong Electrochemiluminescence from MOF Accelerator Enriched Quantum Dots for Enhanced Sensing of Trace CTnI. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 3995–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-L.; Tang, Z.-L.; Zhang, J.-Q.; Chai, Y.-Q.; Zhuo, Y.; Yuan, R. Morphology-Controlled 9,10-Diphenylanthracene Nanoblocks as Electrochemiluminescence Emitters for MicroRNA Detection with One-Step DNA Walker Amplification. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 5298–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, G. Recent Advances in Electrochemiluminescence and Chemiluminescence of Metal Nanoclusters. Molecules 2020, 25, 5208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, S.; Yuan, R. An Ultrasensitive Signal-on Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor Based on Au Nanoclusters for Detecting Acetylthiocholine. Anal. BioAnal. Chem. 2019, 411, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Li, J.; Yang, L.; Fan, D.; Kuang, X.; Sun, X.; Wei, Q.; Ju, H. Hollow Double-Shell CuCo2O4@Cu2O Heterostructures as a Highly Efficient Coreaction Accelerator for Amplifying NIR Electrochemiluminescence of Gold Nanoclusters in Immunoassay. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 7132–7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, L.; Xue, J.; Ren, X.; Zhang, N.; Fan, D.; Wei, Q.; Ma, H. Highly-Branched Cu2O as Well-Ordered Co-Reaction Accelerator for Amplifying Electrochemiluminescence Response of Gold Nanoclusters and Procalcitonin Analysis Based on Protein Bioactivity Maintenance. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 144, 111676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Yang, L.; Xue, J.; Zhang, N.; Fan, D.; Ma, H.; Ren, X.; Hu, L.; Wei, Q. Bioactivity-Protected Electrochemiluminescence Biosensor Using Gold Nanoclusters as the Low-Potential Luminophor and Cu2S Snowflake as Co-Reaction Accelerator for Procalcitonin Analysis. ACS Sens. 2019, 4, 1909–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qu, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Tian, M.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q. Co-Reaction Accelerator-Encapsulated Aggregation-Induced Electrochemiluminescence: Cascade-Sensitized Electron Transfer and Radiative Transitions for Pro-GRP Analysis. Microchem. J. 2025, 209, 112825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Chen, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Progress in Electrochemiluminescence of Nanoclusters: How to Improve the Quantum Yield of Nanoclusters. Analyst 2021, 146, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesari, M.; Workentin, M.S.; Ding, Z. Highly Efficient Electrogenerated Chemiluminescence of Au38 Nanoclusters. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8543–8553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Guo, W.; Su, B. Imaging Cell-Matrix Adhesions and Collective Migration of Living Cells by Electrochemiluminescence Microscopy. Angew. Chem. 2020, 59, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, H.; Wei, Q. A Compatible Sensitivity Enhancement Strategy for Electrochemiluminescence Immunosensors Based on the Biomimetic Melanin-Like Deposition. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 13049–13053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrara, S.; Arcudi, F.; Prato, M.; De Cola, L. Amine-Rich Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Nanodots as a Platform for Self-Enhancing Electrochemiluminescence. Angew. Chem. 2017, 56, 4757–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Chai, Y.; Yuan, R. Highly Efficient Dual-Polar Electrochemiluminescence from Au25 Nanoclusters: The Next Generation of Multibiomarker Detection in a Single Step. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14618–14623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Han, F.; Zhao, X.; Han, D.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z.; Niu, L. Carbon Nitride Quantum Dots Enhancing the Anodic Electrochemiluminescence of Ruthenium(II) Tris(2,2′-Bipyridyl) via Inhibiting the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 15352–15360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Adsetts, J.R.; Ma, J.; Zhang, C.; Hesari, M.; Yang, L.; Ding, Z. Physical Strategy to Determine Absolute Electrochemiluminescence Quantum Efficiencies of Coreactant Systems Using a Photon-Counting Photomultiplier Device. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 22274–22282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Co-Reactants | Luminophores | ΦECL (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triethylamine (TEA) | GSH-Au NCs | 0.42 | [68] |

| BSA-Au NCs | 9.8 | [68] | |

| Ox-Met-Au NCs | 66.1 | [68] | |

| ATT-Au NCs | 78 | [69] | |

| Co2+-Au NCs | 33.8 | [70] | |

| Hydrogel-confined Au NCs | 95 | [52] | |

| Discrete Au NCs | 0.41 | [52] | |

| Tripropylamine (TPrA) | Au25 NCs | 103 | [71] |

| Au12-Ag13 NCs | 400 times higher (vs. Ru(bpy)32+/TPrA) | [72] | |

| Arg-ATT-Au NCs | 67.02 | [73] | |

| Triethanolamine (TEOA) | NAC/Cys-Au NCs | N/A | [63] |

| Met-Au NCs | 75 times higher (vs. BSA-Au NCs) | [62] | |

| Potassium persulfate | Met-Au NCs | 2.33 | [74] |

| BSA-Au NCs | 0.33 | [74] | |

| NAC-Au NCs | 4.11 | [75] | |

| Zn2+-MHA-Au NCs | 10.54 | [76] | |

| Benzoyl peroxide (BPO) | Au NCs | 32 | [59] |

| Hydrazine | BSA-Au NCs | N/A | [77] |

| N,N-diethylethylenediamine (DEDA) | LA-Au NCs | 17 times higher (vs. Ru(bpy)32+/TPrA) | [78] |

| Tris(3-aminoethyl)amine (TAEA) | Pd@CuO-Au NCs | N/A | [79] |

| Polypeptide-biomineralize Au NCs | N/A | [80] | |

| N,N-disopropylethylenediamine (DPEA) | Au-DPEA NCs | 2.1 times higher (vs. Au NCs) | [81] |

| N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) | β-CD-Au NCs | 728 | [82] |

| EDTA | LA-Au NCs | N/A (Higher at pH 7.4 than at more basic and acidic pHs) | [83] |

| HEPES | LA-Au NCs | N/A (Optimal at physiological pH) | [84] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khang, N.P.A.; Kim, J. Co-Reactant Engineering for Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence. Molecules 2025, 30, 4748. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244748

Khang NPA, Kim J. Co-Reactant Engineering for Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4748. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244748

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhang, Nguyen Phuc An, and Joohoon Kim. 2025. "Co-Reactant Engineering for Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4748. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244748

APA StyleKhang, N. P. A., & Kim, J. (2025). Co-Reactant Engineering for Au Nanocluster Electrochemiluminescence. Molecules, 30(24), 4748. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244748