Electrochemical Synthesis of Methoxy-NNO-azoxy Compounds via N=N Bond Formation Between Ammonium N-(methoxy)nitramide and Nitroso Compounds

Abstract

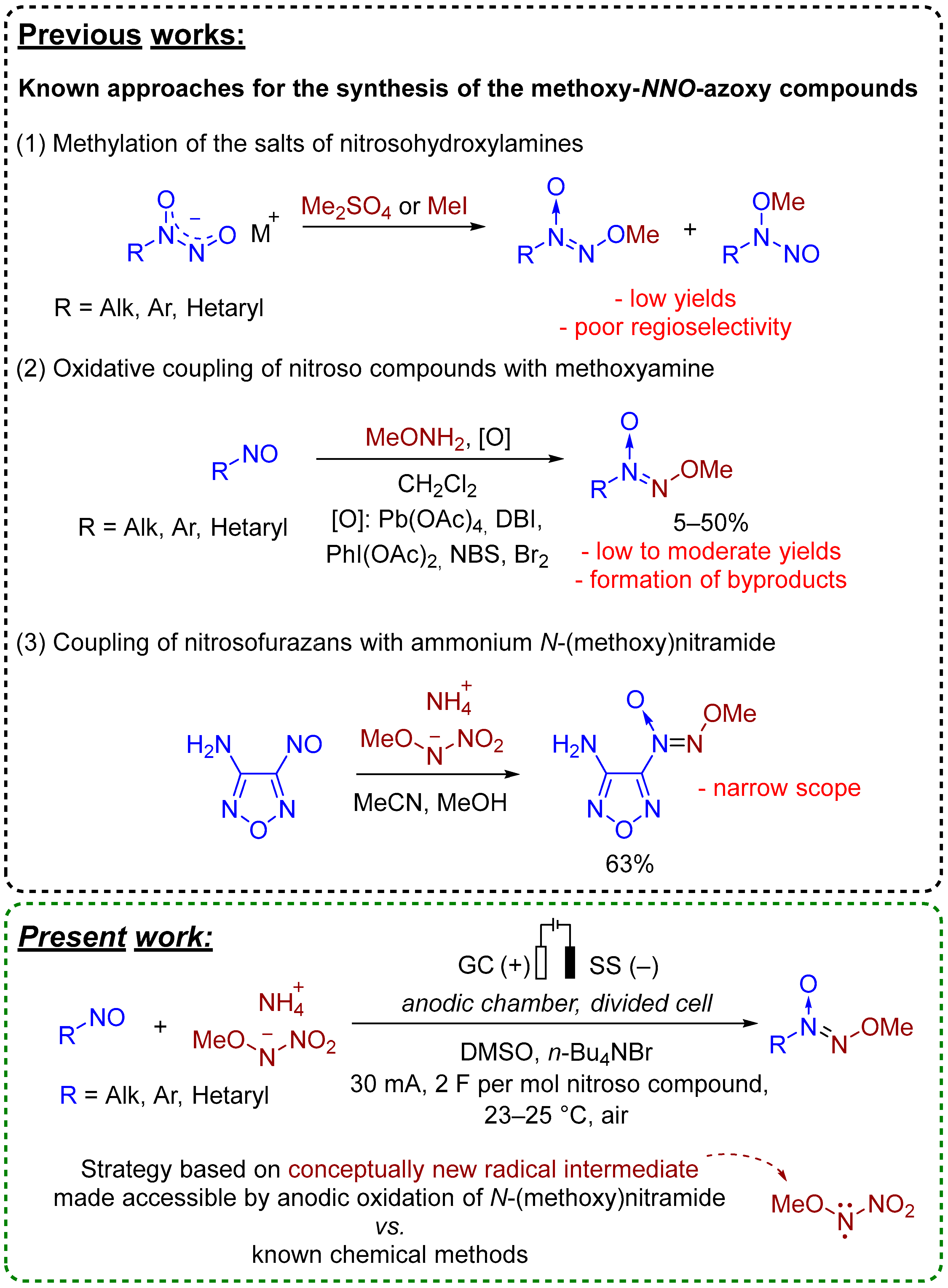

1. Introduction

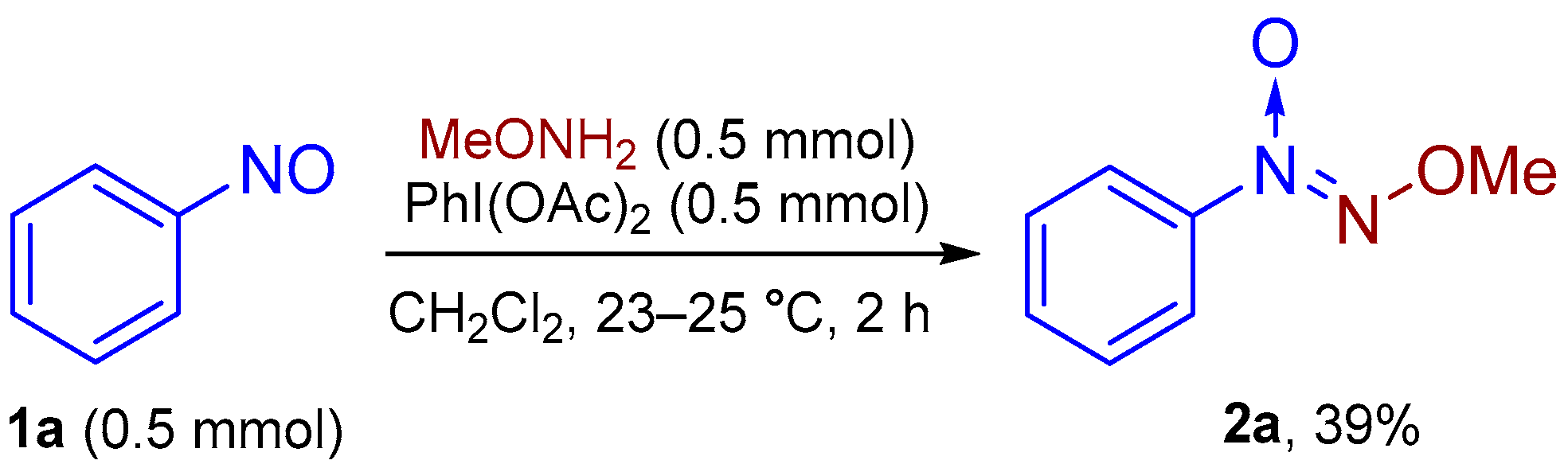

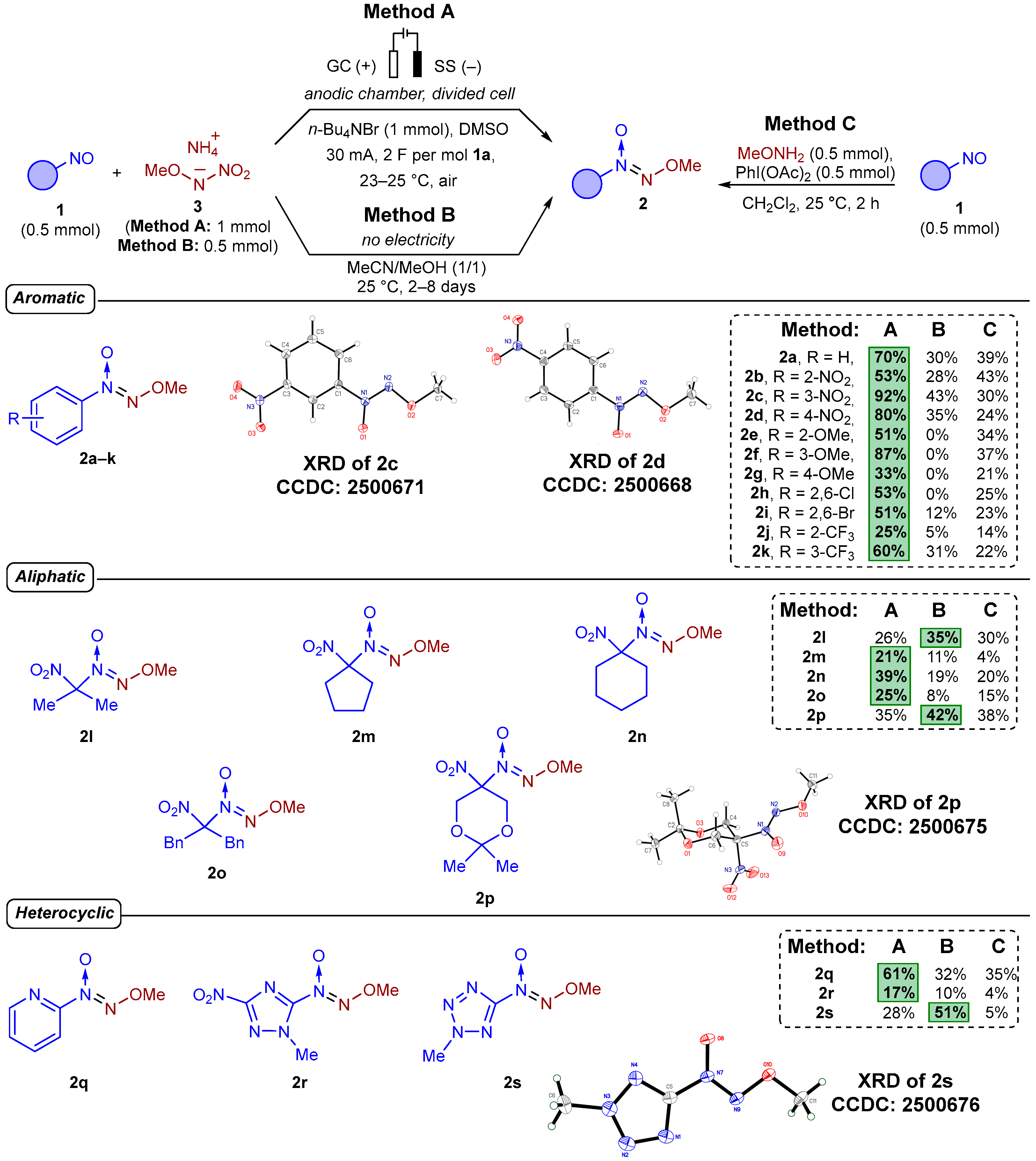

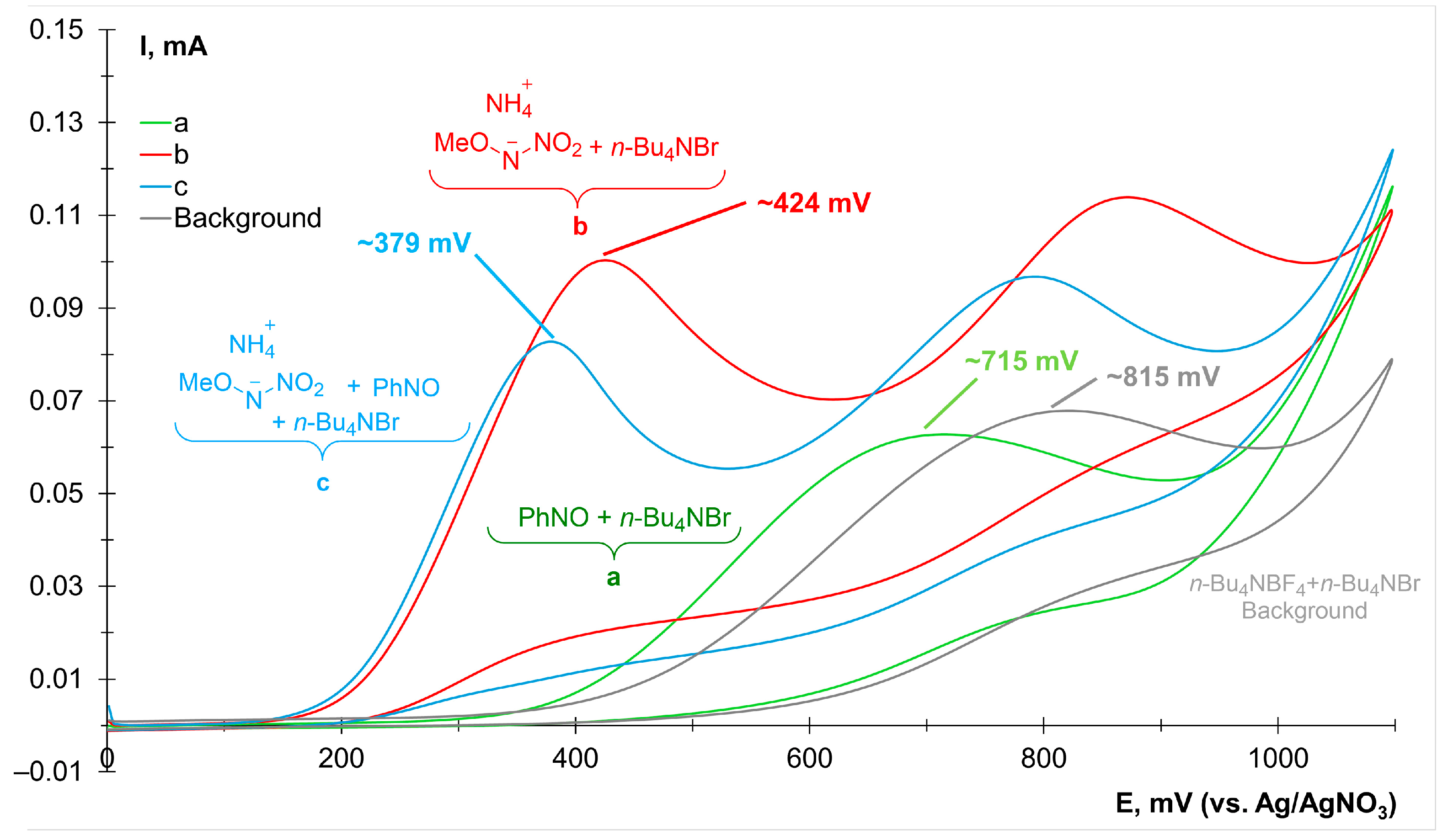

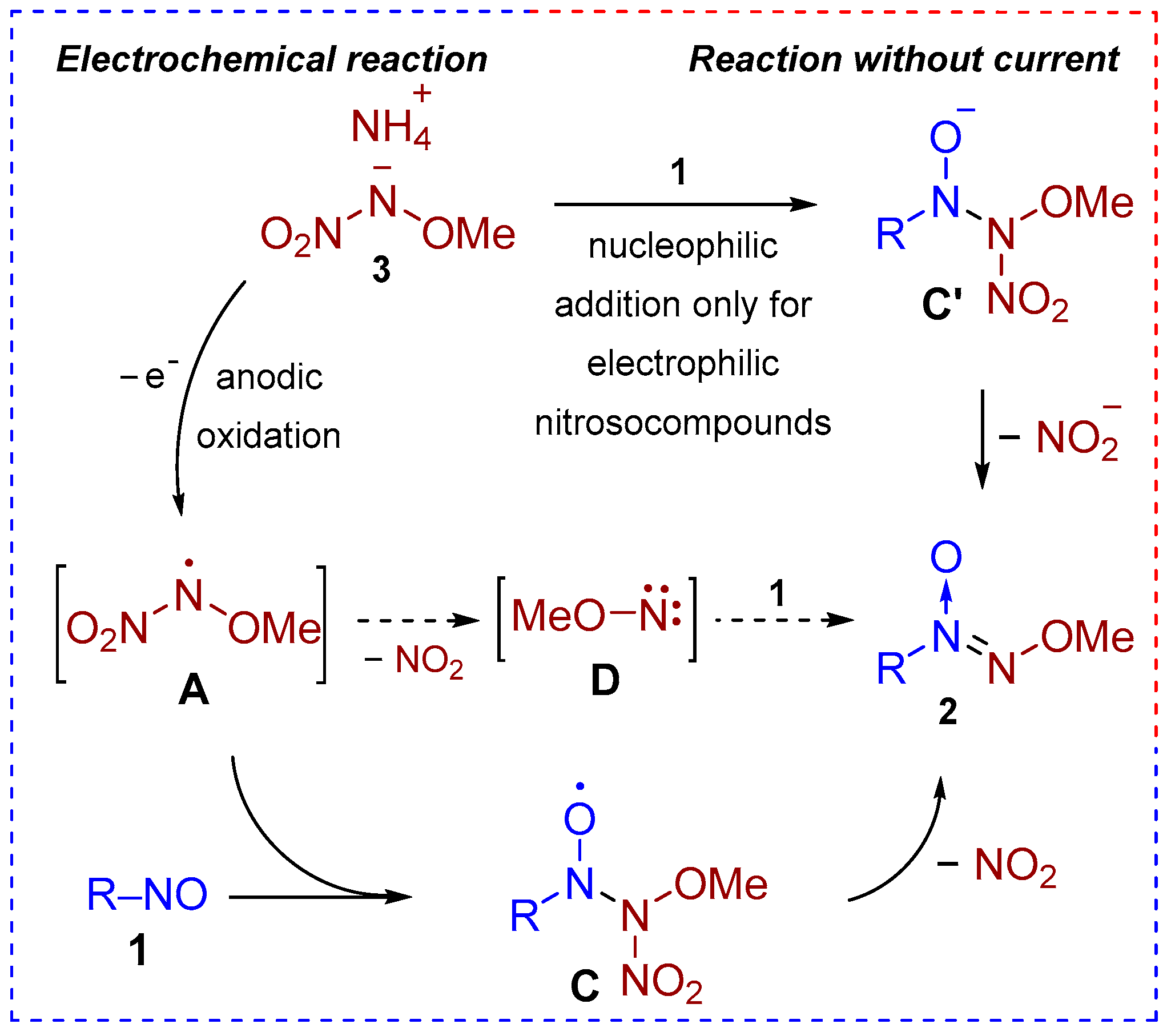

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

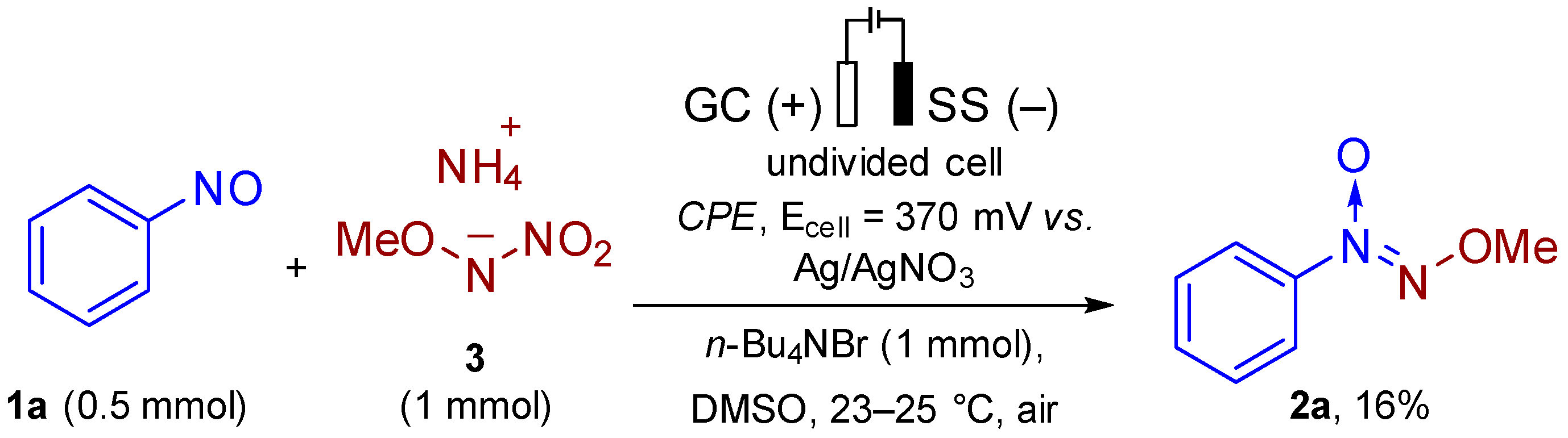

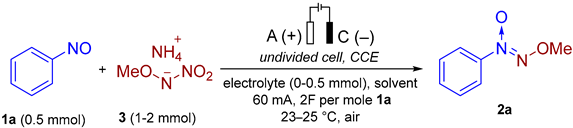

3.1. The General Procedure for the Optimization of the Reaction Conditions for the Synthesis of 1-(Methoxy-NNO-azoxy)benzene (2a) from 1-Nitrosobenzene (1a) via Oxidative Coupling (Experimental Details for Scheme 2)

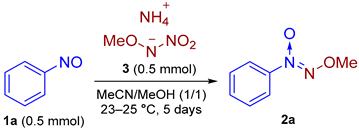

3.2. The General Procedure for the Optimization of the Reaction Conditions for the Synthesis of 1-(Methoxy-NNO-azoxy)benzene (2a) from 1-Nitrosobenzene (1a) and 3 Without Electricity (Experimental Details for Table 1)

3.3. The General Procedure for the Screening of the Reaction Conditions in an Undivided Electrochemical Cell for the Synthesis of (Methoxy-NNO-azoxy)benzene 2a from Nitrosobenzene 1a (Experimental Details for Table 2)

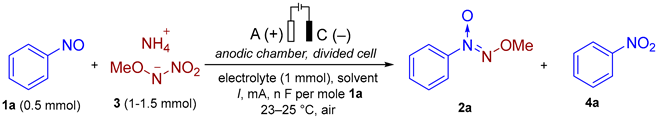

3.4. The General Procedure for the Optimization of the Reaction Conditions in a Divided Electrochemical Cell for the Synthesis of (Methoxy-NNO-azoxy)benzene 2a from Nitrosobenzene 1a and 3 (Experimental Details for Table 3)

3.5. Typical Procedure for Synthesis of (Methoxy-NNO-azoxy)compounds 2a–2s (Experimental Details for Scheme 3)

3.6. Reaction Under Controlled-Potential Electrolysis (Experimental Details for Scheme 4)

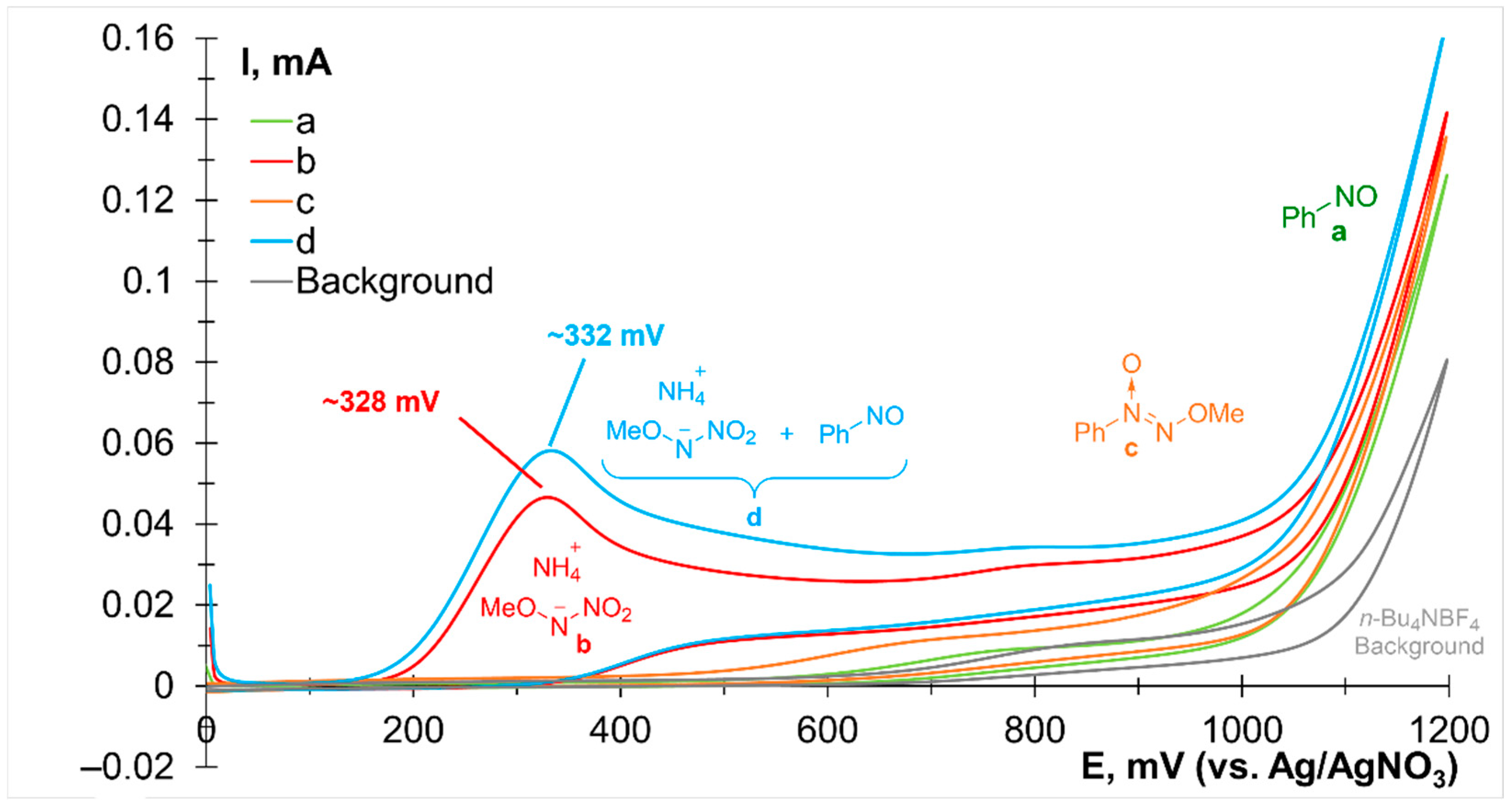

3.7. Cyclic Voltammetry Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, B.; Empel, C.; Yao, W.; Koenigs, R.M.; Xuan, J. Azoxy Compounds—From Synthesis to Reagents for Azoxy Group Transfer Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murarka, S. N-(Acyloxy)Phthalimides as Redox-Active Esters in Cross-Coupling Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 1735–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnikov, A.S.; Krylov, I.B.; Lastovko, A.V.; Yu, B.; Terent’ev, A.O. N-Alkoxyphtalimides as Versatile Alkoxy Radical Precursors in Modern Organic Synthesis. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2022, 11, e202200262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, I.B.; Segida, O.O.; Budnikov, A.S.; Terent’ev, A.O. Oxime-Derived Iminyl Radicals in Selective Processes of Hydrogen Atom Transfer and Addition to Carbon-Carbon π-Bonds. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 363, 2502–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, J.; Morcillo, S.P.; Douglas, J.J.; Leonori, D. Hydroxylamine Derivatives as Nitrogen-Radical Precursors in Visible-Light Photochemistry. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 12154–12163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-S.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, J.-L.; Sun, K.; Chen, X.-L.; Qu, L.-B.; Yu, B. Recent Advances in Amidyl Radical-Mediated Photocatalytic Direct Intermolecular Hydrogen Atom Transfer. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2025, 21, 1306–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C.-Q.; Feng, C. Expedient Access to Structural Complexity via Radical β-Fragmentation of N–O Bonds. Synlett 2025, 36, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoud, F.; Hijazi, A.; Schmitt, M.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. A Review on Recently Proposed Oxime Ester Photoinitiators. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 188, 111901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotin, S.G.; Churakov, A.M.; Dalinger, I.L.; Luk’yanov, O.A.; Makhova, N.N.; Sukhorukov, A.Y.; Tartakovsky, V.A. Recent Advances in Synthesis of Organic Nitrogen–Oxygen Systems for Medicine and Materials Science. Mendeleev Commun. 2017, 27, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotin, S.G.; Churakov, A.M.; Egorov, M.P.; Fershtat, L.L.; Klenov, M.S.; Kuchurov, I.V.; Makhova, N.N.; Smirnov, G.A.; Tomilov, Y.V.; Tartakovsky, V.A. Advanced Energetic Materials: Novel Strategies and Versatile Applications. Mendeleev Commun. 2021, 31, 731–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yount, J.; Piercey, D.G. Electrochemical Synthesis of High-Nitrogen Materials and Energetic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 8809–8840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fershtat, L.L.; Zhilin, E.S. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Biomedical Applications of Heterocyclic NO-Donors. Molecules 2021, 26, 5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz Carvalho, E.; Silva Sousa, E.H.; Bernardes-Génisson, V.; Gonzaga De França Lopes, L. When NO. Is Not Enough: Chemical Systems, Advances and Challenges in the Development of NO. and HNO Donors for Old and Current Medical Issues. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021, 4316–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.R.; Werner, E.W.; O’Brien, A.G.; Baran, P.S. Total Synthesis of Dixiamycin B by Electrochemical Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5571–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jung, H.; Song, F.; Zhu, S.; Bai, Z.; Chen, D.; He, G.; Chang, S.; Chen, G. Nitrene-Mediated Intermolecular N–N Coupling for Efficient Synthesis of Hydrazides. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.C.; Martinelli, J.R.; Stahl, S.S. Cu-Catalyzed Aerobic Oxidative N–N Coupling of Carbazoles and Diarylamines Including Selective Cross-Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9074–9077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, R.F.; Theumer, G.; Kataeva, O.; Knölker, H. Iron-Catalyzed Oxidative C−C and N−N Coupling of Diarylamines and Synthesis of Spiroacridines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gerken, J.B.; Bates, D.M.; Kim, Y.J.; Stahl, S.S. Electrochemical Strategy for Hydrazine Synthesis: Development and Overpotential Analysis of Methods for Oxidative N–N Coupling of an Ammonia Surrogate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12349–12356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankad, N.P.; Müller, P.; Peters, J.C. Catalytic N−N Coupling of Aryl Azides To Yield Azoarenes via Trigonal Bipyramid Iron−Nitrene Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4083–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Sun, B.; Bai, Z.; He, G.; Chen, G.; Wang, H. Nitrene-Mediated Aminative N–N–N Coupling: Facile Access to Triazene 1-Oxides. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 6458–6467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Yang, T.; Tang, N.; Yin, S.-F.; Kambe, N.; Qiu, R. Photo-Induced N–N Coupling of o-Nitrobenzyl Alcohols and Indolines To Give N-Aryl-1-Amino Indoles. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6417–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, P.Y.; Patureau, F.W. Cross-Dehydrogenative N–N Coupling of Aromatic and Aliphatic Methoxyamides with Benzotriazoles. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 3902–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbor, J.P.; Nair, V.N.; Sharp, K.R.; Lohrey, T.D.; Dibrell, S.E.; Shah, T.K.; Walsh, M.J.; Reisman, S.E.; Stoltz, B.M. Development of a Nickel-Catalyzed N–N Coupling for the Synthesis of Hydrazides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 15071–15077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabey, A.; Vemuri, P.Y.; Patureau, F.W. Cross-Dehydrogenative N–N Couplings. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 14343–14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, J.; Yang, F.; Zeng, X. Advances on the Synthesis of N–N Bonds. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 42, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio-Dias, I.E.; Silva-Reis, S.C.; Pires-Lima, B.L.; Correia, X.C.; Costa-Almeida, H.F. A Convenient On-Site Oxidation Strategy for the N-Hydroxylation of Melanostatin Neuropeptide Using Cope Elimination. Synthesis 2022, 54, 2031–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriault, D.; Ly, H.M.; Allen, M.A.; Gill, M.A.; Beauchemin, A.M. Oxidative Syntheses of N,N-Dialkylhydroxylamines. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 8767–8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Hettikankanamalage, A.A.; Crich, D. Diversity-Oriented Synthesis of N,N,O-Trisubstituted Hydroxylamines from Alcohols and Amines by N–O Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14820–14825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Crich, D. Synthesis of O-Tert-Butyl-N,N-Disubstituted Hydroxylamines by N–O Bond Formation. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6396–6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesnikov, V.K.; Golovanov, I.S.; Nelyubina, Y.V.; Aksenova, S.A.; Sukhorukov, A.Y. Crown-Hydroxylamines Are pH-Dependent Chelating N,O-Ligands with a Potential for Aerobic Oxidation Catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Yamamoto, H. Direct N–O Bond Formation via Oxidation of Amines with Benzoyl Peroxide. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2124–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Kawamata, Y.; Baran, P.S. Synthetic Organic Electrochemical Methods Since 2000: On the Verge of a Renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13230–13319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiebe, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Möhle, S.; Rodrigo, E.; Zirbes, M.; Waldvogel, S.R. Electrifying Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 5594–5619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldvogel, S.R.; Janza, B. Renaissance of Electrosynthetic Methods for the Construction of Complex Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7122–7123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontana-Uribe, B.A.; Little, R.D.; Ibanez, J.G.; Palma, A.; Vasquez-Medrano, R. Organic Electrosynthesis: A Promising Green Methodology in Organic Chemistry. Green Chem. 2010, 12, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D.A.; Fershtat, L.L. Electrochemical Generation of Nitrogen-centered Radicals and Its Application for the Green Synthesis of Heterocycles. ChemElectroChem 2024, 11, e202400395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titenkova, K.; Chaplygin, D.A.; Fershtat, L.L. Electrooxidative Synthesis of 1,2,3-Triazolone 1-Amines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2025, 23, 4971–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titenkova, K.; Turpakov, E.A.; Chaplygin, D.A.; Fershtat, L.L. Synthesis of Rare 1,2,3-Triazolium-5-Olates by Electrooxidative Cyclization of α-Aminocarbonyl Hydrazones. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 4434–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvaev, A.D.; Feoktistov, M.A.; Teslenko, F.E.; Fershtat, L.L. Electrochemical Approach Toward Mesoionic 1,2,3-Triazole 1-Imines. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2024, 366, 5050–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S.R. Access to Pyrazolidin-3,5-diones through Anodic N–N Bond Formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9437–9440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieshoff, T.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Moeller, K.D.; Waldvogel, S.R. Insights into the Mechanism of Anodic N–N Bond Formation by Dehydrogenative Coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12317–12324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titenkova, K.; Shuvaev, A.D.; Teslenko, F.E.; Zhilin, E.S.; Fershtat, L.L. Empowering Strategies of Electrochemical N–N Bond Forming Reactions: Direct Access to Previously Neglected 1,2,3-Triazole 1-Oxides. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 6686–6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, Z.; Chen, N.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F. Intramolecular Electrochemical Dehydrogenative N–N Bond Formation for the Synthesis of 1,2,4-Triazolo[1,5-a]Pyridines. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4035–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehl, A.; Gieshoff, T.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S.R. Electrochemical Conversion of Phthaldianilides to Phthalazin-1,4-diones by Dehydrogenative N−N Bond Formation. Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Xu, H. Electrochemical Synthesis of [1,2,3]Triazolo[1,5-a]Pyridines through Dehydrogenative Cyclization. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4177–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniek, J.C.; Grünewald, M.; Winter, J.; Schollmeyer, D.; Waldvogel, S.R. Electrochemical Synthesis of N,N′-Disubstituted Indazolin-3-Ones via an Intramolecular Anodic Dehydrogenative N–N Coupling Reaction. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 8180–8186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, S.; Han, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, M.; Wu, Y.; Ma, L.; Niu, L.; Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Hu, W.; et al. Tunable Electrochemical C−N versus N−N Bond Formation of Nitrogen-Centered Radicals Enabled by Dehydrogenative Dearomatization: Biological Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11583–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadatnabi, A.; Mohamadighader, N.; Nematollahi, D. Convergent Paired Electrochemical Synthesis of Azoxy and Azo Compounds: An Insight into the Reaction Mechanism. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 6488–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, X.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, B. Potential-Tuned Selective Electrosynthesis of Azoxy-, Azo- and Amino-Aromatics over a CoP Nanosheet Cathode. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2020, 7, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breising, V.M.; Kayser, J.M.; Kehl, A.; Schollmeyer, D.; Liermann, J.C.; Waldvogel, S.R. Electrochemical Formation of N,N′-Diarylhydrazines by Dehydrogenative N–N Homocoupling Reaction. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 4348–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, E.; Hou, Z.; Xu, H. Electrochemical Synthesis of Tetrasubstituted Hydrazines by Dehydrogenative N–N Bond Formation. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 39, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traube, W. Ueber Synthesen Stickstoffhaltiger Verbindungen Mit Hülfe Des Stickoxyds. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1898, 300, 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.V.; Kierstead, R.W.; Wright, G.F. The Stable Alkylation Products of Organonitrosohydroxylamines. Can. J. Chem. 1959, 37, 679–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, R.B.; Wintner, C. The Methoxazonyl Group. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 10, 2689–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, E.; Hädicke, E.; Reuther, W. “Isonitramines”: Nitrosohydroxylamines or Hydroxydiazenium Oxides? Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 2457–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandovskii, V.N.; Dobrodumova, E.Y.; Tselinskii, I.V. Azo and Azoxy Compounds. V. Alkylation of the Salts of Bis(Nitrosohydroxylamino)Methane. Synthesis of 1,7-Dialkyl-1,7-Dioxa-2,3,5,6-Tetraaza-2,5-Heptadiene 3,5-Dioxides. J. Org. Chem. USSR 1980, 16, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artsybasheva, Y.P.; Ioffe, B.V. Nitrosocompounds as Acceptors of the Alkoxynitrenes. Synthesis of 1-Tert-Alkyl-2-Alkoxydiazene 1-Oxides from C-Nitrosocompounds. J. Org. Chem. USSR 1982, 18, 1802–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Zyuzin, I.N.; Lempert, D.B. Synthesis and Properties of N-Alkyl-N’-Methoxydiazene N-Oxides. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 1985, 34, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandovskii, V.N.; Gidaspov, B.V.; Tselinskii, I.V. Azo and Azoxy Compounds. XI. New Versions of the Synthesis of Derivatives of 1-Alkoxydiazene 2-Oxides. J. Org. Chem. USSR 1987, 23, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Luk’yanov, O.A.; Smirnov, G.A.; Vasil’ev, A.M. Synthesis of N’-Methoxydiazene N-Oxides from Methoxyamine and Nitroso Compounds. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 1990, 39, 1966–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohle, D.S.; Imonigie, J.A. Cyclohexadienone Diazeniumdiolates from Nitric Oxide Addition to Phenolates. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 5685–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, J.; Huhn, T.; Groth, U.; Jochims, J.C. Nitrosation of Sugar Oximes: Preparation of 2-Glycosyl-1-hydroxydiazene-2-oxides. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, G.A.; Luk’yanov, O.A. Synthesis and Some Properties of the Salts of N-(Het)Aryl-N′-Hydroxydiazene N-Oxides. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xie, W.; Janczuk, A.J.; Wang, P.G. O-Alkylation of Cupferron: Aiming at the Design and Synthesis of Controlled Nitric Oxide Releasing Agents. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 4333–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Xie, W.; Ramachandran, N.; Mutus, B.; Janczuk, A.J.; Wang, P.G. O-Alkylation Chemistry of Neocupferron. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, K.R.A.; Chowdhury, M.A.; Velázquez, C.A.; Huang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Das, D.; Yu, G.; Suresh, M.R.; Knaus, E.E. Celecoxib Prodrugs Possessing a Diazen-1-Ium-1,2-Diolate Nitric Oxide Donor Moiety: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Nitric Oxide Release Studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4544–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyuzin, I.N.; Golovina, N.I.; Lempert, D.B.; Nechiporenko, G.N.; Shilov, G.V. 1,1-Bis(Methoxy-NNO-Azoxy)Ethene. Synthesis and X-Ray Diffraction Analysis. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2008, 57, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grachev, V.P.; Zyuzin, I.N.; Kurmaz, S.V.; Vaganov, E.V.; Komendant, R.I.; Lempert, D.B. Poly(Methoxy-NNO-Azoxyethene), a New Polymer for Active Binders in Solid Composite Propellants. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2020, 69, 2312–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, A.A.; Leonov, N.E.; Klenov, M.S.; Smirnov, G.A.; Strelenko, Y.A.; Fedyanin, I.V.; Kon’kova, T.S.; Matyushin, Y.N.; Pivkina, A.N.; Tartakovsky, V.A. First Comprehensive Study of Energetic (Methoxy-NNO-Azoxy)Furazans: Novel Synthetic Route, Characterization, and Property Analysis. Energ. Mater. Front. 2025, 6, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnikov, A.S.; Leonov, N.E.; Klenov, M.S.; Shevchenko, M.I.; Dvinyaninova, T.Y.; Krylov, I.B.; Churakov, A.M.; Fedyanin, I.V.; Tartakovsky, V.A.; Terent’ev, A.O. Ammonium Dinitramide as a Prospective N–NO2 Synthon: Electrochemical Synthesis of Nitro-NNO-Azoxy Compounds from Nitrosoarenes. Molecules 2024, 29, 5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerich, O.; Lund, H. (Eds.) Organic Electrochemistry; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-429-13168-4. [Google Scholar]

- Scherschel, N.F.; Zeller, M.; Piercey, D.G. Energetic Azoxy-Coupled Tetrazoles. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2024, 61, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, G.H.; McCloskey, C.M.; Stuart, F.A. Nitrosobenzene. Organic Syntheses. 1945, 25, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscales, S.; Csaky, A.G. Synthesis of Di(hetero)arylamines from Nitrosoarenes and Boronic Acids: A General, Mild, and Transition-Metal-Free Coupling. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1667–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, M.; Pakladek, Z.; Deiana, M.; Matcztszyn, K. Molecular design and structural characterization of photoresponsive azobenzene-based polyamide units. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 180, 108501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasz, I.; Biljan, I.; Novak, P.; Mestrovic, E.; Plavec, J.; Mali, G.; Smrecki, V.; Vancik, H. Cross-dimerization of nitrosobenzenes in solution and in solid state. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 918, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teders, M.; Pogodaev, A.A.; Bojanov, G.; Huck, W.T.S. Reversible Photoswitchable Inhibitors Generate Ultrasensitivity in Out-of-Equilibrium Enzymatic Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 5709–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, A.; Lin, Y.; Takeishi, A.; Yoshida, K. Enantioselective Nitroso Aldol Reaction Catalyzed by a Chiral Phosphine–Silver Complex. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 2016, 5355–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, S.; Cheng, J. Catalyzed bilateral cyclization of aldehydes with nitrosos toward unsymmetrical acridines proceeding with C–H functionalization enabled by a transient directing group. ChemComm 2017, 53, 6263–6266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.R.; Bayer, R.P. A simple method for the direct oxidation of aromatic amines to nitroso compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82, 3454–3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibiletti, F.; Simonetti, M.; Nicholas, K.M.; Palmisano, G.; Parravicini, M.; Imbesi, F.; Tollari, S.; Penoni, A. One-pot synthesis of meridianins and meridianin analogues via indolization of nitrosoarenes. Tetrahedron 2010, 66, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, I.F.; Hecquet, L.; Fessner, W. Transketolase Catalyzed Synthesis of N-Aryl Hydroxamic Acids. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2021, 364, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehse, K.; Herpel, M. New NO donors with antithrombotic and vasodilating activities, part 19: Pseudonitroles and their dimeric azodioxides. Arch. Pharm. Pharm Med. Chem. 1998, 331, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nametkin, S.S. About cyclohexylpseudonitrol. Zhurnal Russkago Fiziko-Khimicheskago Obshchestva 1910, 42, 585–586. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, W.; Earl, J.C.; Kenner, J.; Luciano, A.A. The nitration of oximes. J. Chem. Soc. 1932, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk’yanov, O.A.; Salamonov, Y.B.; Bass, A.G.; Strelenko, Y.A. N′-(α-acetoximinoalkyl)diazene-N-oxides and some of their transformations. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1991, 40, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.C.; Tseng, C.-P.; Rampal, J.B. Conversion of a Primary Amino Group into a Nitroso Group. Synthesis of Nitroso-Substituted Heterocycles. J. Org. Chem. 1982, 47, 552–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagal, L.I.; Pevzner, M.S.; Egorov, A.P.; Samarenko, V.Y. Heterocyclic Nitro Compounds VI. Reaction of 1-methyl-3,5-dinitro-1,2,4-triazole with hydrazines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1970, 6, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demko, Z.P.; Bartsch, M.; Sharpless, K.B. Primary amides. A general nitrogen source for catalytic asymmetric aminohydroxylation of olefins. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 2221–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, Y.; Ding, Y.; Cao, F.; Zhang, J.; Peng, S. Nanometre-sized titanium dioxide-catalyzed reactions of nitric oxide with aliphatic cyclic and aromatic amines. Chem. Commun. 2009, 13, 1763–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, Version 1.171.41.106a; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction: Abingdon, UK, 2021.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 229–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent | Temperature, °C | Time | Yield 2a, % |

| 1 | DMSO | 25 | 3 h | 5 |

| 2 | DMSO | 25 | 16 h | 9 |

| 3 | DMSO | 25 | 1 day | 12 |

| 4 | DMSO | 25 | 2 days | 22 |

| 5 | MeCN | 25 | 1 day | 4 |

| 6 | MeCN | 25 | 3 days | 8 |

| 7 | MeCN | 25 | 5 days | 14 |

| 8 | MeCN | 25 | 9 days | 20 |

| 9 | MeCN/MeOH (1/1) | 25 | 1 day | 9 |

| 10 | MeCN/MeOH (1/1) | 25 | 3 days | 19 |

| 11 | MeCN/MeOH (1/1) | 25 | 5 days | 30 |

| 12 | MeCN/MeOH (1/1) | 50 | 1 day | 16 |

| 13 | MeCN/MeOH (1/1) | 50 | 3 days | 15 |

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Conditions | Yield 2a, % b |

| 1 | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (2 mmol), NH4BF4 (0.5 mmol), CF(+)/Ptw(−), MeCN | 10 |

| 2 | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (2 mmol), n-Bu4NBF4 (0.5 mmol), Pt(+)/Ptw(−), MeCN/H2O = 4/1 | 16 |

| 3 | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (2 mmol), Pt(+)/Ptw(−), MeOH | 20 |

| 4 | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (2 mmol), Pt(+)/Ptw(−), DMF | 11 |

| 5 | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (2 mmol), n-Bu4NBF4 (0.5 mmol), Pt(+)/Ptw(−), CH2Cl2/H2O = 4/1 | <5 |

| 6 c | 1a (0.5 mmol), 3 (1 mmol), n-Bu4NBr (1 mmol), GC(+)/SS(−), DMSO | 19 |

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Solvent | Electrolyte | Molar Ratio 1a:3 | Electrodes (+/−) | F per Mole 1a | I, mA | Yield, b 2a/4a |

| 1 | MeCN/H2O (8/4) | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 31/41 |

| 2 | MeCN | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 10/36 |

| 3 | MeOH | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 23/31 |

| 4 | DMF | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | <5/<5 |

| 5 | Acetone | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 23/41 |

| 6 | THF/H2O (8/4) | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 41/29 |

| 7 | TFE | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 20/48 |

| 8 | HFIP | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 17/34 |

| 9 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:1 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 47/11 |

| 10 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 59/15 |

| 11 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBF4 | 1:3 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 48/17 |

| 12 | DMSO | LiClO4 | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 63/19 |

| 13 | DMSO | NH4BF4 | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 58/18 |

| 14 | DMSO | n-Bu4NClO4 | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 55/20 |

| 15 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 67/15 |

| 16 | DMSO | n-Bu4NI | 1:2 | Pt/Pt | 2 | 30 | 17/n.d. |

| 17 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | Pt/SS | 2 | 30 | 70/14 |

| 18 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | Pt/Ni | 2 | 30 | 70/14 |

| 19 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | Pt/GC | 2 | 30 | 70/15 |

| 20 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | Ni/SS | 2 | 30 | 10/n.d. |

| 21 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | C/SS | 2 | 30 | 75/17 |

| 22 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | CF/SS | 2 | 30 | 70/15 |

| 23 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 2 | 30 | 78 (70)/17 (14) |

| 24 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 2 | 20 | 71/19 |

| 25 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 2 | 15 | 67/20 |

| 26 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 2 | 10 | 60/21 |

| 27 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 1 | 30 | 70/15 |

| 28 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 1.5 | 30 | 69/16 |

| 29 | DMSO | n-Bu4NBr | 1:2 | GC/SS | 3 | 30 | 65/17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Budnikov, A.S.; Kulikov, A.A.; Klenov, M.S.; Leonov, N.E.; Krylov, I.B.; Terent’ev, A.O.; Tartakovsky, V.A. Electrochemical Synthesis of Methoxy-NNO-azoxy Compounds via N=N Bond Formation Between Ammonium N-(methoxy)nitramide and Nitroso Compounds. Molecules 2025, 30, 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244723

Budnikov AS, Kulikov AA, Klenov MS, Leonov NE, Krylov IB, Terent’ev AO, Tartakovsky VA. Electrochemical Synthesis of Methoxy-NNO-azoxy Compounds via N=N Bond Formation Between Ammonium N-(methoxy)nitramide and Nitroso Compounds. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244723

Chicago/Turabian StyleBudnikov, Alexander S., Andey A. Kulikov, Michael S. Klenov, Nikita E. Leonov, Igor B. Krylov, Alexander O. Terent’ev, and Vladimir A. Tartakovsky. 2025. "Electrochemical Synthesis of Methoxy-NNO-azoxy Compounds via N=N Bond Formation Between Ammonium N-(methoxy)nitramide and Nitroso Compounds" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244723

APA StyleBudnikov, A. S., Kulikov, A. A., Klenov, M. S., Leonov, N. E., Krylov, I. B., Terent’ev, A. O., & Tartakovsky, V. A. (2025). Electrochemical Synthesis of Methoxy-NNO-azoxy Compounds via N=N Bond Formation Between Ammonium N-(methoxy)nitramide and Nitroso Compounds. Molecules, 30(24), 4723. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244723