Hydroxyl Functionalization Effects on Carbene–Graphene for Enhanced Ammonia Gas Sensing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

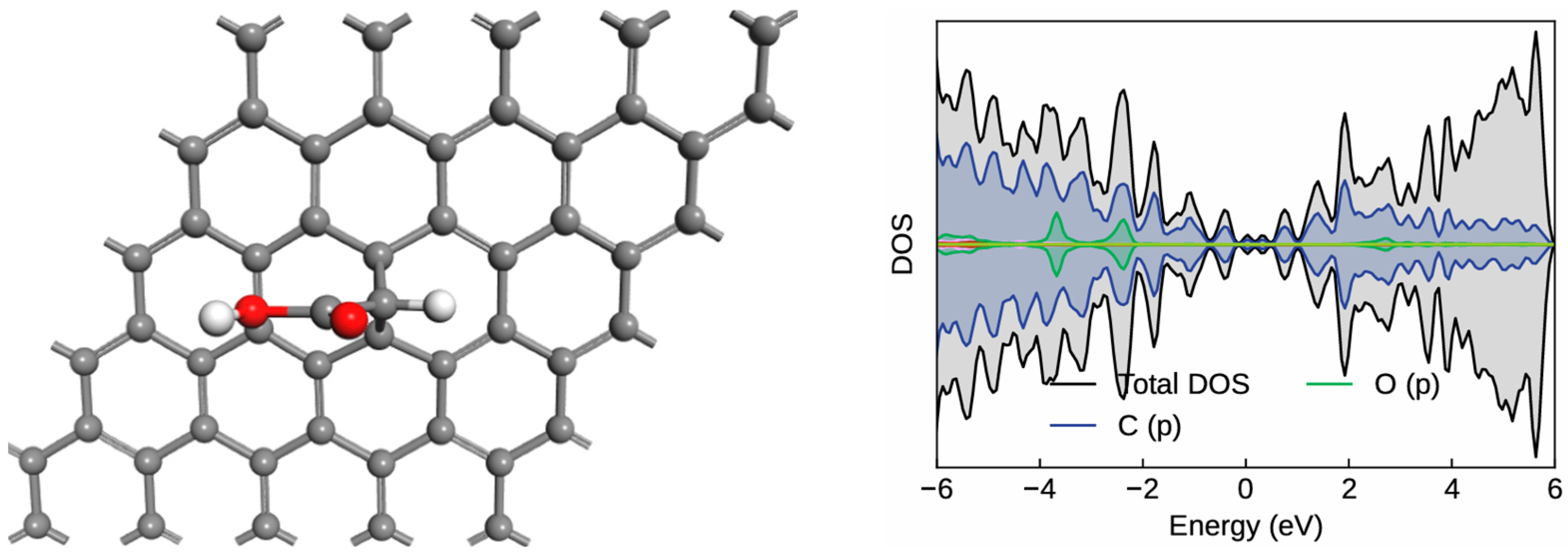

2.1. Graphene Functionalization with Carbene and Hydroxyl Groups

2.2. NH3 Gas Sensing on the OH-Modified Graphene–Carbene Surface

2.3. Desorption Time (τ)

2.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Threatt, S.D.; Rees, D.C. Biological nitrogen fixation in theory, practice, and reality: A perspective on the molybdenum nitrogenase system. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dopazo, J.A.; Fernández-Seara, J.; Sieres, J.; Uhía, F.J. Theoretical analysis of a CO2–NH3 cascade refrigeration system for cooling applications at low temperatures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2009, 29, 1577–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, J. Enhanced gas sensing mechanisms of metal oxide heterojunction gas sensors. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2016, 32, 1087–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashami, S.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Trincavelli, M. Detecting changes of a distant gas source with an array of MOX gas sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 16404–16419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, L.; Zeng, W.; Zhou, Q. Anti-interference detection of mixed NOX via In2O3-based sensor array combining with neural network model at room temperature. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 463, 132857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Meng, L.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Z.; Huang, X.; Qin, Y. Adjustment of oxygen vacancy states in ZnO and its application in ppb-level NO2 gas sensor. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bu, M.; Hu, N.; Zhao, L. An overview on room-temperature chemiresistor gas sensors based on 2D materials: Research status and challenge. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 248, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, G.; Jeong, Y.; Hong, Y.; Wu, M.; Hong, S.; Shin, W.; Park, J.; Jang, D.; Lee, J.-H. SO2 gas sensing characteristics of FET-and resistor-type gas sensors having WO3 as sensing material. Solid-State Electron. 2020, 165, 107747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumyantsev, S.; Liu, G.; Shur, M.S.; Potyrailo, R.A.; Balandin, A.A. Selective gas sensing with a single pristine graphene transistor. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 2294–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-J.; Jin, J.; Zhang, H.; Wu, P.; Cai, C.-X. Graphene: Synthesis, functionalization and applications in chemistry. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2010, 26, 2073–2086. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Zhong, S.; Bin, Y.; Jiang, X.; Cui, H. Ni-decorated WS2-WSe2 heterostructure as a novel sensing candidate upon C2H2 and C2H4 in oil-filled transformers: A first-principles investigation. Mol. Phys. 2025, e2492391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhou, A.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Lan, X.; Bai, H.; Li, L. Bottom-up preparation of ultrathin 2D aluminum oxide Nanosheets by duplicating graphene oxide. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, N.-W.; Wang, B.; Yuan, S.; Yu, L. Advanced pillared designs for two-dimensional materials in electrochemical energy storage. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 5496–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wu, D.; Mai, Y.; Pan, H.; Cao, J.; Yang, C.; Zhang, F.; Feng, X. A two-dimensional hybrid with molybdenum disulfide nanocrystals strongly coupled on nitrogen-enriched graphene via mild temperature pyrolysis for high performance lithium storage. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 14679–14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Guo, X.; Wu, W.; Wang, G. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) as high-performance electrode materials for Lithium-based batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Tian, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Liu, Y.; Hirtz, T.; Wu, R.; Gou, G.; Qiao, Y.; Yang, Y. High thermal conductivity 2D materials: From theory and engineering to applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.; Wan, C.; McNally, T. Thermal conductivity of 2D nano-structured graphitic materials and their composites with epoxy resins. 2D Mater. 2017, 4, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.-e.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, L.; Li, S.; Cao, L.; He, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, C.; Liu, K.; Du, H.; Fan, X. High conductivity of 2D hydrogen substituted graphyne nanosheets for fast recovery NH3 gas sensors at room temperature. Carbon 2024, 225, 119090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, A.A.; Sinthika, S.; Premkumar, S.; Vigneshwaran, J.; Karazhanov, S.Z.; Jose, S.P. DFT study of NH3 adsorption on 2D monolayer MXenes (M2C, M = Cr, Fe) via oxygen functionalization: Suitable materials for gas sensors. FlatChem 2022, 31, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hasnaawei, S.; Altalbawy, F.M.A.; Kanjariya, P.; Kumar, A.; S, K.K.; Shit, D.; Ray, S.; Kamolova, N.; Sinha, A. Adsorption properties of N containing N2O, NH3, NO and NO2 gas molecules on the novel TiO2 doped MoSe2 heterostructure system: A systematic DFT study. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 258, 114039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, T.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, W.; Zhou, Q. Ni decorated ReS2 monolayer as gas sensor or adsorbent for agricultural greenhouse gases NH3, NO2 and Cl2: A DFT study. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 38, 102114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Basem, A.; Hanoon, Z.A.; Al-Bahrani, M.; Mgm, J.; Jie, J.C.; Muzammil, K.; Hasan, M.A.; Islam, S.; Zainul, R. Adsorption of NH3, HCHO, SO2, and Cl2 gasses on the o-B2N2 monolayer for its potential application as a sensor. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 147, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badran, H.M.; Aal, S.A.; Ammar, H.Y. Detection of XH3 gas (X=N, P, and As) on Cu- functionalized C2N nanosheet: DFT perspective. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 58, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, D.; Wu, Q.; Chang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, A. Hf3C2O2 MXene: A promising NH3 gas sensor with high selectivity/sensitivity and fast recover time at room temperature. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 40, 109467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakami, S.; Yakushiji, S.; Ohba, T. Graphene Functionalization by O2, H2, and Ar Plasma Treatments for Improved NH3 Gas Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 1992–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldulaijan, S.; Ajeebi, A.M.; Jedidi, A.; Messaoudi, S.; Raouafi, N.; Dhouib, A. Surface modification of graphene with functionalized carbenes and their applications in the sensing of toxic gases: A DFT study. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 19607–19616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baachaoui, S.; Aldulaijan, S.; Sementa, L.; Fortunelli, A.; Dhouib, A.; Raouafi, N. Density Functional Theory Investigation of Graphene Functionalization with Activated Carbenes and Its Application in the Sensing of Heavy Metallic Cations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 26418–26428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baachaoui, S.; Sementa, L.; Hajlaoui, R.; Aldulaijan, S.; Fortunelli, A.; Dhouib, A.; Raouafi, N. Tailoring Graphene Functionalization with Organic Residues for Selective Sensing of Nitrogenated Compounds: Structure and Transport Properties via QM Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 15474–15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Sun, H.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, J.; Zhao, L. Room-temperature NH3 sensing of graphene oxide film and its enhanced response on the laser-textured silicon. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, M.; Jiang, C.; Song, S.; Li, T.; Sun, M.; Chen, W.; Peng, H. Highly sensitive graphene-based ammonia sensor enhanced by electrophoretic deposition of MXene. Carbon 2023, 202, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodu, M.; Pärna, R.; Avarmaa, T.; Renge, I.; Kozlova, J.; Kahro, T.; Jaaniso, R. Gas-Sensing Properties of Graphene Functionalized with Ternary Cu-Mn Oxides for E-Nose Applications. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkov, P.V.; Glukhova, O.E. Carboxylated Graphene Nanoribbons for Highly-Selective Ammonia Gas Sensors: Ab Initio Study. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Debliquy, M.; Lahem, D.; Yan, Y.; Raskin, J.-P. A Review on Functionalized Graphene Sensors for Detection of Ammonia. Sensors 2021, 21, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.G.; Choi, J.; Jeong, H.E.; Song, K.; Jeon, S.; Cha, J.; Baeck, S.-H.; Shim, S.E.; Qian, Y. A comprehensive study of various amine-functionalized graphene oxides for room temperature formaldehyde gas detection: Experimental and theoretical approaches. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 529, 147189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, D.; Ren, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, J.; Ruoff, R.S. Adsorption/desorption and electrically controlled flipping of ammonia molecules on graphene. New J. Phys. 2010, 12, 125011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadore, A.R.; Mania, E.; Alencar, A.B.; Rezende, N.P.; de Oliveira, S.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Chacham, H.; Campos, L.C.; Lacerda, R.G. Enhancing the response of NH3 graphene-sensors by using devices with different graphene-substrate distances. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 266, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Vu, T.C.; Hoang, H.V.; Huang, W.-F.; Pham, H.T.; Nguyen, H.M.T. How are Hydroxyl Groups Localized on a Graphene Sheet? ACS Omega 2022, 7, 37221–37228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhat, F.; Coudert, F.-X.; Bocquet, M.-L. Structure and chemistry of graphene oxide in liquid water from first principles. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasert, K.; Sutthibutpong, T. Unveiling the Fundamental Mechanisms of Graphene Oxide Selectivity on the Ascorbic Acid, Dopamine, and Uric Acid by Density Functional Theory Calculations and Charge Population Analysis. Sensors 2021, 21, 2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhvalov, D.W. DFT modeling of the covalent functionalization of graphene: From ideal to realistic models. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 7150–7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Qin, J. Theoretical insight into two-dimensional M-Pc monolayer as an excellent material for formaldehyde and phosgene sensing. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 543, 148805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F.M. Adsorption of H2O, NH3, CO, NO2, and NO on graphene: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 125416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, J. Ammonia adsorption on graphene and graphene oxide: A first-principles study. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2013, 7, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Saito, S. Adsorption of molecules on nitrogen-doped graphene: A first-principles study. In Proceedings of the International Symposium “Nanoscience and Quantum Physics 2012” (nanoPHYS’12), Tokyo, Japan, 17–19 December 2012; p. 012002. [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter. 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a longrange dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkelman, G.; Arkel, A.D.; Becke, A.D. A Two-Dimensional Grid-Based Algorithm for the Voronoi Dissection of the Charge Density. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 63, 064103. [Google Scholar]

- Momma, K.; Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.; Zhou, K.-G.; Xie, K.-F.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, H.-L.; Peng, Y. Tuning the electronic structure and transport properties of graphene by noncovalentfunctionalization: Effects of organic donor, acceptor and metal atoms. Nanotechnology 2010, 21, 065201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Above OH Group | Below OH Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Eb (eV) | Eb (eV) | |

| 1 | −1.24 | −1.72 |

| 2 | −1.31 | −1.72 |

| 3 | −1.31 | −1.76 |

| 4 | −1.24 | −1.72 |

| 5 | −0.88 | −0.93 |

| 6 | −1.00 | −0.86 |

| 7 | −1.00 | −0.88 |

| 8 | −0.83 | −0.93 |

| 9 | −0.89 | −0.93 |

| 10 | −0.81 | −0.91 |

| 11 | −0.81 | −0.90 |

| 12 | −1.01 | −0.93 |

| 13 | −1.48 | −1.25 |

| 14 | −1.48 | −1.26 |

| 15 | −0.80 | −0.95 |

| 16 | −1.02 | −0.96 |

| 17 | −0.90 | −0.94 |

| Geometric Parameters | –OH Above C13 | –OH Above C14 | –OH Below C3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eb (eV) | −1.48 | −1.48 | −1.76 |

| d1 (Å) | 1.52 | 1.54 | 1.5 |

| d2 (Å) | 1.54 | 1.52 | 1.55 |

| d3 (Å) | 1.54 | 1.54 | 1.53 |

| d4 (Å) | 1.23 | 1.22 | 1.22 |

| d5 (Å) | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| d6 (Å) | 1.48 | 1.48 | 1.48 |

| d7 (Å) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.98 |

| α (°) | 60.2 | 60.3 | 60.2 |

| β (°) | 59.5 | 60.3 | 58.3 |

| γ1 (°) | 108.6 | 108.4 | 106.6 |

| h1 (Å) | 0.65 | 0.66 | −0.31 |

| H (Å) | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.50 |

| 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.52 |

| Geometric Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Eb (eV) | −1.97 |

| d1 (Å) | 1.53 |

| d2 (Å) | 1.53 |

| d3 (Å) | 1.52 |

| d4 (Å) | 1.22 |

| d5 (Å) | 0.98 |

| d6 (Å) | 1.48 |

| d7 (Å) | 0.98 |

| d8 (Å) | 1.49 |

| d9 (Å) | 0.98 |

| α (°) | 58.8 |

| β (°) | 58.9 |

| γ1 (°) | 108.2 |

| γ2 (°) | 107.8 |

| h1 (Å) | 0.56 |

| h2 (Å) | 0.56 |

| H (Å) | 0.50 |

| 0.52 |

| System | Position | Eads (eV) | d (Å) | Q | (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1OH | Above C13 | −0.70 | 1.58 (N-H), 2.54 (H-O) | −2.89 | 5.7 |

| 1OH | Below C3 | −0.64 | 1.63 (N-H), 2.34 (H-O) | −2.91 | 6.5 |

| 2OH | Above C13, below C2 | −1.78 | 1.60 (N-H), 2.49 (H-O) | −2.89 | 7.82 |

| 2OH | Above C14, below C3 | −1.83 | 1.60 (N-H), 2.42 (H-O) | −2.90 | 5.41 |

| 2OH | Above C13 and C14 | −0.75 | 1.56 (N-H), 2.47 (H-O) | −2.88 | 3.94 |

| 2OH | Below C3 and C2 | −0.62 | 1.65 (N-H), 2.33 (H-O) | 2.92 | 2.58 |

| Modification/Functionalization Position | Reported NH3 Adsorption Range | Sensing Implication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine graphene | Weak (physisorption) | Very low intrinsic sensitivity; rapid recovery | [43] |

| Graphene oxide (epoxide/hydroxyl) | Moderate to strong | Improved sensitivity; some GO sites show near-chemisorption | [44] |

| N-doped graphene | Weak to moderate | Better sensor response than pristine; still often reversible at room temperature | [45] |

| Carboxylated graphene nanoribbons | Moderate to strong | Improved sensitivity via engineered binding sites | [33] |

| Carbene functionalized graphene | Moderate to strong | Improved sensitivity via engineered binding sites | [28] |

| Graphene with functionalized carbenes | Moderate to strong | Potential selectivity | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassanian, A.A.; Soliman, K.A.; Hasanin, T.; Jedidi, A.; Dhouib, A. Hydroxyl Functionalization Effects on Carbene–Graphene for Enhanced Ammonia Gas Sensing. Molecules 2025, 30, 4726. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244726

Hassanian AA, Soliman KA, Hasanin T, Jedidi A, Dhouib A. Hydroxyl Functionalization Effects on Carbene–Graphene for Enhanced Ammonia Gas Sensing. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4726. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244726

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassanian, Athar A., Kamal A. Soliman, Tawfiq Hasanin, Abdesslem Jedidi, and Adnene Dhouib. 2025. "Hydroxyl Functionalization Effects on Carbene–Graphene for Enhanced Ammonia Gas Sensing" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4726. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244726

APA StyleHassanian, A. A., Soliman, K. A., Hasanin, T., Jedidi, A., & Dhouib, A. (2025). Hydroxyl Functionalization Effects on Carbene–Graphene for Enhanced Ammonia Gas Sensing. Molecules, 30(24), 4726. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244726