Biosorption of Aspirin, Salicylic Acid, Ketoprofen, and Naproxen in Aqueous Solution by Walnut Shell Biochar: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Biosorbent

2.2. Effect of Adsorption Parameters

2.2.1. Effect of Solution pH

2.2.2. Effect of Biosorbent Dosage

2.2.3. Effect of Initial Concentration

2.2.4. Effect of Contact Time

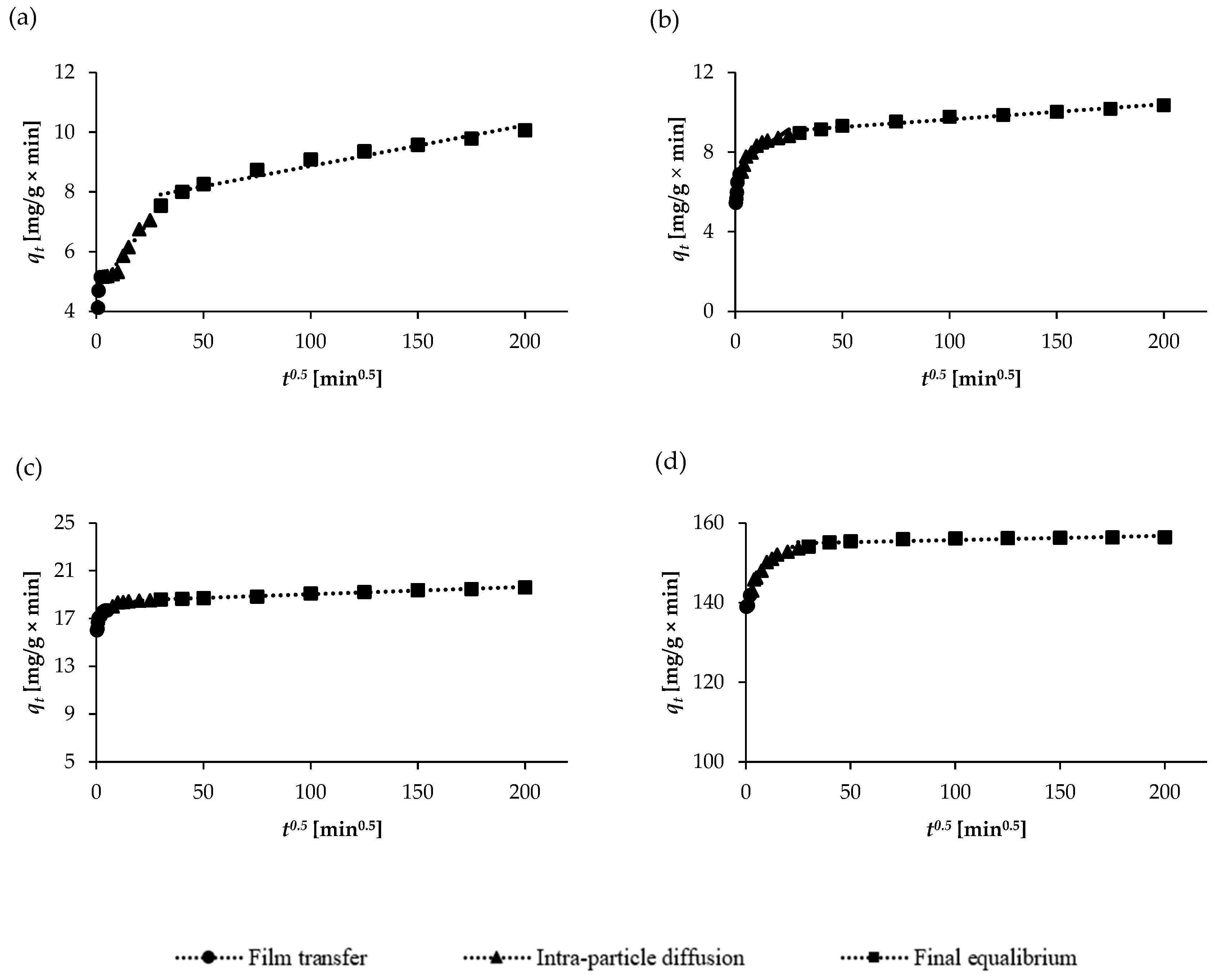

2.3. Adsorption Kinetics Studies

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm Studies

2.5. Comparison with Other Adsorbents

2.6. Desorption and Regeneration Studies

2.7. Estimation of the Cost of WSB Preparation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Preparation of Biosorbent

3.3. Characterization of Biosorbent

3.3.1. pH at Point of Zero Charge (pHpzc)

3.3.2. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

3.3.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy–Energy-Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

3.3.4. Biosorption Experiments

- Batch Adsorption Experiments

- Adsorption Kinetics

- Adsorption Isotherms

3.4. Desorption Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papadaki, M.I.; Mendoza-Castillo, D.I.; Reynel-Avila, H.E.; Bonilla-Petriciolet, A.; Georgopoulos, S. Nut Shells as Adsorbents of Pollutants: Research and Perspectives. Front. Chem. Eng. 2021, 3, 640983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S. Agro waste based adsorbents: Application in cleaning of pharmaceuticals and personal care products from wastewater. In Development in Wastewater Treatment Research and Processes Emerging Technologies for Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products: State of the Art, Challenges and Future Perspectives, 1st ed.; Shah, M.P., Ghosh, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.H.M.L.M.; Gros, M.; Rodriguez-Mozaz, S.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Pena, A.; Barceló, D.; Montenegro, M.C.B.S.M. Contribution of hospital effluents to the load of pharmaceuticals in urban wastewaters: Identification of ecologically relevant pharmaceuticals. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461–462, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B.L.; Ferreira, D.P.; Borges, S.F.; Ferreira, A.M.; Holanda, F.H.; Ucella-Filho, J.G.M.; Cruz, R.A.S.; Birolli, W.G.; Luque, R.; Ferreira, I.M. Diclofenac, ibuprofen, and paracetamol biodegradation: Overconsumed non-steroidal anti-inflammatories drugs at COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1207664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberer, T.; Feldmann, D. Contribution of effluents from hospitals and private households to the total loads of diclofenac and carbamazepine in municipal sewage effluents—Modeling versus measurements. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 122, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hifney, A.F.; Zien-Elabdeen, A.; Adam, M.S.; Gomaa, M. Biosorption of ketoprofen and diclofenac by living cells of the green microalgae Chlorella sp. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 69242–69252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izadi, P.; Izadi, P.; Salem, R.; Papry, S.A.; Magdouli, S.; Publicharla, R.; Brar, S.K. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the environment: Where were we and how far we have come? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, S.F.; Trindade, T.; Daniel-da-Silva, A.L. Enhanced Removal of Non-Steroidal Inflammatory Drugs from Water by Quaternary Chitosan-Based Magnetic Nanosorbents. Coatings 2021, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoun, M.C.; Elliott, H.A.; Preisendanz, H.E.; Williams, C.F.; Knopf, A.; Watson, J.E. Adsorption of pharmaceuticals from aqueous solutions using biochar derived from cotton gin waste and guayule bagasse. Biochar 2020, 3, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Kumar, R.; Pittman, C.U., Jr.; Mohan, D. Ciprofloxacin and acetaminophen sorption onto banana peel biochars: Environmental and process parameter influences. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, H.; Ali, Y.A.E.H.; Azzouz, A.; Chraka, A.; Bouzit, L.; Stitou, M. Optimization and application of walnut shell-driver biochar for efficient removal of salicylic acid from wastewater: Experiment and theoretical study. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2025, 221, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şensoy, R.; Kabak, B.; Kendüzler, E. Kinetic and isothermal studies of naproxen adsorption from aqueous solutions using walnut shell biochar. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2024, 137, 1031–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhao, B.; Qu, Z.; Pan, J.; Guo, Q. Adsorption of metformin in aqueous system by biochars derived from different biomasses: Performance and mechanisms. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 727, 138438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwa, M.S.; Lahib, F.M.; Zainab, T.A.S.; Onyeaka, H. Walnut shells as sustainable adsorbent for the removal of medical waste from wastewater. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 27, 698–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țurcanu, A.A.; Matei, E.; Râpă, M.; Predescu, A.M.; Berbecaru, A.C.; Coman, G.; Predescu, C. Walnut Shell Biowaste Valorization via HTC Process for the Removal of Some Emerging Pharmaceutical Pollutants from Aqueous Solutions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoun, M.C.; Knopf, A.; Preisendanz, H.E.; Vozenilek, N.; Elliott, H.A.; Mashtare, M.L.; Velegol, S.; Veith, T.L.; Williams, C.F. Fixed bed column experiments using cotton gin waste and walnut shells-derived biochar as low-cost solutions to removing pharmaceuticals from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 2023, 330, 138591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Chaubey, A.K.; Pittmann, C.U.; Mohan, D. Aqueous ibuprofen sorption by using activated walnut shell biochar: Process optimization and cost estimation. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2022, 1, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunay, S.; Koklu, R.; Imamoglu, M. Highly Efficient and Environmentally Friendly Walnut Shell Carbon for the Removal of Ciprofloxacin, Diclofenac, and Sulfamethoxazole from Aqueous Solutions and Real Wastewater. Processes 2024, 12, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Hou, Y.; Pei, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Gan, L. Walnut Shell Biomass Triggered Formation of Fe3C-Biochar Composite for Removal of Diclofenac by Activating Percarbonate. Catalysts 2024, 14, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anfar, Z.; Zbair, M.; Ahsiane, H.A.; Jada, A.; El Alem, N. Microwave assisted green synthesis of Fe2O3/biochar for ultrasonic removal of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory pharmaceuticals. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11371–11380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, F.; Liu, W.; Ma, L. Adsorption behavior of graphite-like walnut shell biochar modified with ammonia for ciprofloxacin in aqueous solution. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2025, 100, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, E.; Branà, M.T.; Altomare, C.; Loffredo, E. Biochar and Hydrochar from Waste Biomass Promote the Growth and Enzyme Activity of Soil-Resident Ligninolytic Fungi. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Sarmah, A.K.; Kwon, E.E. Production and Formation of Biochar. In Biochar from Biomass and Waste Fundamentals and Applications, 1st ed.; Ok, Y.S., Tsang, D.C.W., Bolan, N., Novak, J.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Mena, L.E.; Pécora, A.A.B.; Beraldo, A.L. Slow Pyrolysis of Bamboo Biomass: Analysis of Biochar Properties. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014, 37, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewódzki, P.; Lemanowicz, J.; Debska, B.; Haddad, S.A. Soil Enzyme Activity Response under the Amendment of Different Types of Biochar. Agronomy 2022, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Bhattacharya, T.; Shaikh, W.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Sarkar, D.; Biswas, J.K. Biochar Modification Methods for Augmenting Sorption of Contaminants. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2022, 8, 519–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, O.S.; Alao, O.C.; Alagbada, T.C.; Olatunde, A.M. Biosorption of ibuprofen using functionalized bean husks. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2019, 13, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, P.; Banerjee, S.; Kumar, S.; Sadhukhan, S.; Halder, G. Elucidation of ibuprofen uptake capability of raw and steam activated biochar of Aegle marmelos shell: Isotherm, kinetics, thermodynamics and cost estimation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 118, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, H.; Grich, A.; Naboulsi, A.; Bouzid, T.; El mersly, L.; El mouchtari, E.M.; Abdelmajid, R.; El himri, M.; Rafqah, S.; El haddad, M. Enhancing adsorption efficiency of pharmaceutical pollutants using activated carbon derived from walnut shells: Investigating experimental design, mechanisms, and DFTCalculations. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 153, 112077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccar, R.; Sarrà, M.; Bouzid, J.; Feki, M.; Blánquez, P. Removal of pharmaceutical compounds by activated carbon prepared from agricultural by-product. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 211–212, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.J.; Hameed, B.H. Adsorption behavior of salicylic acid on biochar as derived from the thermal pyrolysis of barley straws. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Fiore, S.; Berruti, F. Adsorption of methyl orange and methylene blue on activated biocarbon derived from birchwood pellets. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 191, 107446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomul, F.; Arslan, Y.; Kabak, B.; Trak, D.; Tran, H.N. Adsorption process of naproxen onto peanut shell-derived biosorbent: Important role of n–π interaction and van der Waals force. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2020, 96, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Ye, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Guo, M.; Li, Q.; Li, J. Interactions between adsorbents and adsorbates in aqueous solutions. Pure Appl. Chem. 2020, 92, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.M.; Abbas, M.; Trari, M. Understanding the rate-limiting step adsorption kinetics onto biomaterials for mechanism adsorption control. Prog. React. Kinet. Mech. 2024, 49, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somashekara, D.; Mulky, L. Sequestration of Contaminants from Wastewater: A Review of Adsorption Processes. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023, 10, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, F.; Lacin, O.; Ediz, E.F.; Demir, F. Adsorption capacity, isotherm, kinetic, and thermodynamic studies on adsorption behavior of malachite green onto natural red clay. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2020, 40, e13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Taggart, M.A.; McKenzie, C.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Pap, S.; Gibb, S. Utilizing low-cost natural waste for the removal of pharmaceuticals from water: Mechanisms, isotherms and kinetics at low concentrations. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 227, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomul, F.; Arslan, Y.; Kabak, B.; Trak, D.; Kendüzler, E.; Lima, E.C.; Tran, H.N. Peanut shells-derived biochars prepared from different carbonization processes: Comparison of characterization and mechanism of naproxen adsorption in water. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 137828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouasfi, N.; Zbair, M.; Bouzikri, S.; Anfar, Z.; Bensitel, M.; Ait Ahsaine, H.; Sabbar, E.; Khamliche, L. Selected pharmaceuticals removal using algae derived porous carbon: Experimental, modeling and DFT theoretical insights. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 9792–9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deokar, S.K.; Jadhav, A.R.; Pathak, P.D.; Mandavgane, S.A. Biochar from microwave pyrolysis of banana peel: Characterization and utilization for removal of benzoic and salicylic acid from aqueous solutions. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 27671–27682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.K.; Kim, W.H.; Park, J.; Cho, J.; Jeong, T.Y.; Park, P.K. Application of Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms to predict adsorbate removal efficiency or required amount of adsorbent. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 28, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuithitikul, K.; Phromrak, R.; Saengngoen, W. Utilization of chemically treated cashew-nut shell as potential adsorbent for removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous solution. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasuphan, W.; Praphairaksit, N.; Imyim, A. Removal of ibuprofen, diclofenac, and naproxen from water using chitosan-modified waste tire crumb rubber. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 294, 111554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jmai, S.; Jmai, L.; Guiza, S.; Lamari, H.; Launay, F.; Karoui, S.; Mohamed, B. Removal of Naproxen from Aqueous Solutions using Eco-Friendly Bio-Adsorbent Prepared from Orange Peels. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024, 235, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.D.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, H.L.; Nguyen, M.Q.; Tran, T.M.; Nguyen, M.V.; Nguyen, T.L.; Ngo, T.M.V.; Namakamura, K.; Tsubota, T. Adsorption characteristics of ciprofloxacin and naproxen from aqueous solution using bamboo biochar. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 3071–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’diaye, A.D.; Kankou, M.S.A. Sorption of Aspirin from Aqueous Solutions using Rice Husk as Low Cost Sorbent. J. Environ. Treat. Tech. 2020, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Boushara, R.S.; Ngadi, N.; Wong, S.; Mohamud, M.Y. Removal of aspirin from aqueous solution using phosphoric acid modified coffee waste adsorbent. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 2960–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, N.C.; Tentler Prola, L.D.; Passig, F.H.; Freire, F.B.; Ferreira, R.C.; Vinicius de Liz, M.; Querne de Carvalho, K. Thermal treated sugarcane bagasse for acetylsalicylic acid removal: Dynamic and equilibrium studies, cycles of reuse and mechanisms. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 104, 5803–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smiljanić, D.; de Gennaro, B.; Izzo, F.; Langella, A.; Daković, A.; Germinario, C.; Rottinghaus, G.E.; Spasojević, M.; Mercurio, M. Removal of emerging contaminants from water by zeolite-rich composites: A first approach aiming at diclofenac and ketoprofen. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020, 298, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, A.C.; dos Reis, G.S.; Pavan, F.A.; Lima, É.C.; Foletto, E.L.; Dotto, G.L. Improvement of activated carbon characteristics by sonication and its application for pharmaceutical contaminant adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 24713–24725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preigschadt, I.A.; Bevilacqua, R.C.; Netto, M.S.; Georgin, J.; Franco, D.S.P.; Mallmann, E.S.; Pinto, D.; Foletto, E.L.; Dotto, G.L. Optimization of ketoprofen adsorption from aqueous solutions and simulated effluents using H2SO4 activated Campomanesia guazumifolia bark. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 2122–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, P.D.; Mandavgane, S.A.; Kulkarni, B.D. Utilization of banana peel for the removal of benzoic and salicylic acid from aqueous solutions and its potential reuse. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 12717–12729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaloul, N.; Oulego, P.; Rendueles, M.; Ghorbal, A.; Díaz, M. Novel biosorbents from almond shells: Characterization and adsorption properties modeling for Cu(II) ions from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, R.L.; Wu, F.C.; Juang, R.S. Characteristics and applications of the Lagergren’s first-order equation for adsorption kinetics. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2010, 41, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.H.; Clayton, W.R. Application of Elovich Equation to the Kinetics of Phosphate Release and Sorption in Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1980, 44, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Rethinking of the intraparticle diffusion adsorption kinetics model: Interpretation, solving methods and applications. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musah, M.; Azeh, Y.; Mathew, J.; Umar, M.; Abdulhamid, Z.; Muhammad, A. Adsorption Kinetics and Isotherm Models: A Review. Caliphate J. Sci. Tech. 2022, 4, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| WSB | WSB + ASP | WSB + SAL | WSB + NAP | WSB + KET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Weight % | Element | Weight % | Element | Weight % | Element | Weight % | Element | Weight % |

| C | 89.34 | C | 89.94 | C | 90.34 | C | 91.09 | C | 89.53 |

| O | 8.14 | O | 8.87 | O | 8.85 | O | 8.28 | O | 9.64 |

| Mg | 0.07 | Mg | 0.06 | Mg | 0.05 | Mg | 0.04 | Mg | 0.06 |

| Al | 0.01 | P | 0.12 | Si | 0.03 | Si | 0.03 | Si | 0.04 |

| Si | 0.01 | S | 0.04 | P | 0.06 | P | 0.07 | P | 0.07 |

| P | 0.10 | Cl | 0.33 | S | 0.03 | S | 0.03 | S | 0.03 |

| S | 0.03 | K | 0.15 | Cl | 0.09 | Cl | 0.15 | Cl | 0.24 |

| Cl | 0.05 | Ca | 0.39 | K | 0.14 | K | 0.07 | K | 0.05 |

| K | 1.80 | Fe | 0.03 | Ca | 0.30 | Ca | 0.18 | Ca | 0.25 |

| Ca | 0.36 | Cu | 0.09 | Cu | 0.10 | Fe | 0.01 | Cu | 0.08 |

| Cu | 0.09 | Cu | 0.06 | ||||||

| Total: | 100.00 | Total: | 100.00 | Total: | 100.00 | Total: | 100.00 | Total: | 100.00 |

| Analyte | C0 [mg/L] | qe [mg/g] | Pseudo-First-Order | Pseudo-Second-Order | Elovich | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qcal [mg/g] | k1 [1/min] | R2 | qcal [mg/g] | k2 [g/mg × min] | R2 | α [mg/g × min] | β [g/mg] | R2 | |||

| ASP | 100 | 15.28 ± 0.98 | 10.58 ± 0.32 | 0.0021 ± 0.0004 | 0.7318 | 14.16 ± 0.35 | 0.0086 ± 0.0008 | 0.9956 | 33.6 ± 3.5 | 0.9985 ± 0.0116 | 0.9202 |

| SAL | 50 | 10.31 ± 0.82 | 3.23 ± 0.22 | 0.0055 ± 0.0009 | 0.5939 | 9.77 ± 0.17 | 0.0405 ± 0.0018 | 0.9998 | 3683.8 ± 241.3 | 1.4349 ± 0.0265 | 0.9729 |

| KET | 25 | 19.96 ± 0.37 | 3.27 ± 0.05 | 0.0062 ± 0.0005 | 0.5726 | 19.57 ± 0.55 | 0.0317 ± 0.002 | 0.9998 | 2.9 × 1013 ± 2.1 × 1012 | 1.9209 ± 0.1504 | 0.9726 |

| NAP | 30 | 156.44 ± 2.32 | 14.27 ± 0.36 | 0.0108 ± 0.00147 | 0.6390 | 156.25 ± 3.25 | 0.0114 ± 0.0011 | 1.0000 | 1.7 × 1018 ± 2.0 × 1017 | 0.2942 ± 0.02 | 0.9545 |

| Analyte | kp1 [mg/g/min0.5] | kp2 [mg/g/min0.5] | kp3 [mg/g/min0.5] | C1 [mg/g] | C2 [mg/g] | C3 [mg/g] | R12 | R22 | R32 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP | 0.7632 | 0.0480 | 0.0074 | 5.452 | 7.666 | 8.926 | 0.8613 | 0.9095 | 0.9705 |

| SAL | 0.0669 | 0.0046 | 0.0008 | 4.092 | 4.480 | 4.604 | 0.9678 | 1.0000 | 0.9932 |

| KET | 0.2704 | 0.0128 | 0.0058 | 16.463 | 18.212 | 18.466 | 0.7117 | 1.0000 | 0.9871 |

| NAP | 2.0013 | 0.3313 | 0.0075 | 137.760 | 145.624 | 155.060 | 0.9382 | 0.8997 | 0.7894 |

| Model | Adsorption Parameters | ASP | SAL | KET | NAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | KL (L/mg) | 0.358 ± 0.027 | 0.352 ± 0.018 | 0.501 ± 0.045 | 0.936 ± 0.095 |

| qmax (mg/g) | 20.92 ± 0.324 | 33.55 ± 0.361 | 39.84 ± 0.954 | 172.41 ± 4.583 | |

| R2 | 0.9949 | 0.9998 | 0.9364 | 0.9832 | |

| RL | 0.053 ± 0.001 | 0.102 ± 0.006 | 0.138 ± 0.014 | 0.010 ± 0.002 | |

| Freundlich | KF (mg/g)(L/mg)1/n | 7.044 ± 0.157 | 11.087 ± 0.284 | 18.272 ± 0.833 | 88.783 ± 9.985 |

| n | 4.002 ± 0.098 | 3.220 ± 0.040 | 5.308 ± 0.249 | 3.868 ± 0.265 | |

| R2 | 0.9487 | 0.9252 | 0.9164 | 0.9848 |

| Biosorbent | NSAIDs | qmax [mg/g] | Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan-modified waste tire rubber | NAP | 2.3 | pH: 6 teq: 60–120 min trt: - | [45] |

| Peanut shells | NAP | 55.1 | pH: 7 teq: 120 min trt: chemical modification (H2O2) | [34] |

| Orange peel | NAP | 28.1 | pH: 4 teq: 30 min trt: - | [46] |

| Bamboo biochar | NAP | 56.5 | pH: 3 teq: 90 min trt: - | [47] |

| Walnut shell biochar | NAP | 58.8 | pH: 6.84 teq: 240 min trt: - | [12] |

| Olive-waste cake biochar | NAP KET | 39.5 24.7 | pH: 2.01 teq: 26 h trt: chemical modification (H3PO4) | [31] |

| Rice husk | ASP | 47.0 | pH: 2 teq: 180 min treatment: - | [48] |

| Coffee waste biochar | ASP | 490.1 | pH: - teq: 30–60 min trt: chemical modification (H3PO4) | [49] |

| Sugarcane bagasse biochar | ASP | 32.7 | pH: 4 teq: 120 min trt: - | [50] |

| Green microalgae, Chlorella sp. | KET | 0.6 | pH: 6 teq: 60 min trt: - | [6] |

| Zeolites | KET | 1.8 | pH: 5 teq: 20–30 min trt: chemical modification (Cetylpyridinium chloride or Arquad® 2HT-75) | [51] |

| Babassu coconut husk biochar | KET | 89.2 | pH: 2 teq: 300 min trt: - | [52] |

| Babassu coconut husk biochar | KET | 79.1 | pH: 2 teq: 300 min trt: physical modification (sonication) | [52] |

| Campomanesia guazumifolia bark | KET | 158.3 | pH: 2 teq: 180 min trt: chemical modification (H2SO4) | [53] |

| Banana peel | SAL | 9.8 | pH: 3.3 teq: 14 h trt: - | [54] |

| Barley straw biochar | SAL | 189.2 | pH: 3 teq: 11 h trt: - | [32] |

| Walnut shell biochar | ASP | 33.6 | pH: 2 | This work |

| SAL | 20.9 | teq: 4 min for KET, NAP | ||

| KET | 39.8 | teq: 400 min for SAL, ASP | ||

| NAP | 172.4 | trt: - |

| Desorption Agent | Desorption Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|

| MeOH | 98 ± 2 |

| ACN | 65 ± 6 |

| H2O, pH 2 | 7 ± 2 |

| H2O, pH 4 | 11 ± 4 |

| H2O, pH 8 | 14 ± 3 |

| H2O, pH 10 | 15 ± 1 |

| H2O, pH 6.5, 80 °C | 17 ± 3 |

| Particulars | Subsections | Cost Breakdown | Total Cost ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raw-material processing | Collection of raw material | Collected from local farm | 0 |

| Size reduction cost | Size reduction was performed manually | 0 | |

| Preparation of WSB | Carbonization cost | [Hours × unit × unit cost] 1.75 h × 4.5 kW × 0.29 $ | 2.28 |

| Size reduction cost | [Hours × unit × unit cost] × 7 * 0.33 h × 1.25 kW × 0.29 $ × 7 | 0.42 | |

| Net cost | 2.70 | ||

| 10% of overall cost | 0.27 | ||

| Total cost | 2.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Narloch, I.; Wejnerowska, G.; Wojewódzki, P. Biosorption of Aspirin, Salicylic Acid, Ketoprofen, and Naproxen in Aqueous Solution by Walnut Shell Biochar: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies. Molecules 2025, 30, 4731. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244731

Narloch I, Wejnerowska G, Wojewódzki P. Biosorption of Aspirin, Salicylic Acid, Ketoprofen, and Naproxen in Aqueous Solution by Walnut Shell Biochar: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4731. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244731

Chicago/Turabian StyleNarloch, Izabela, Grażyna Wejnerowska, and Piotr Wojewódzki. 2025. "Biosorption of Aspirin, Salicylic Acid, Ketoprofen, and Naproxen in Aqueous Solution by Walnut Shell Biochar: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4731. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244731

APA StyleNarloch, I., Wejnerowska, G., & Wojewódzki, P. (2025). Biosorption of Aspirin, Salicylic Acid, Ketoprofen, and Naproxen in Aqueous Solution by Walnut Shell Biochar: Characterization, Equilibrium, and Kinetic Studies. Molecules, 30(24), 4731. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244731