Proline-Free Local Turn via N-Oxidation: Crystallographic and Solution Evidence for a Six-Membered N–O⋯H–N Ring

Abstract

1. Introduction

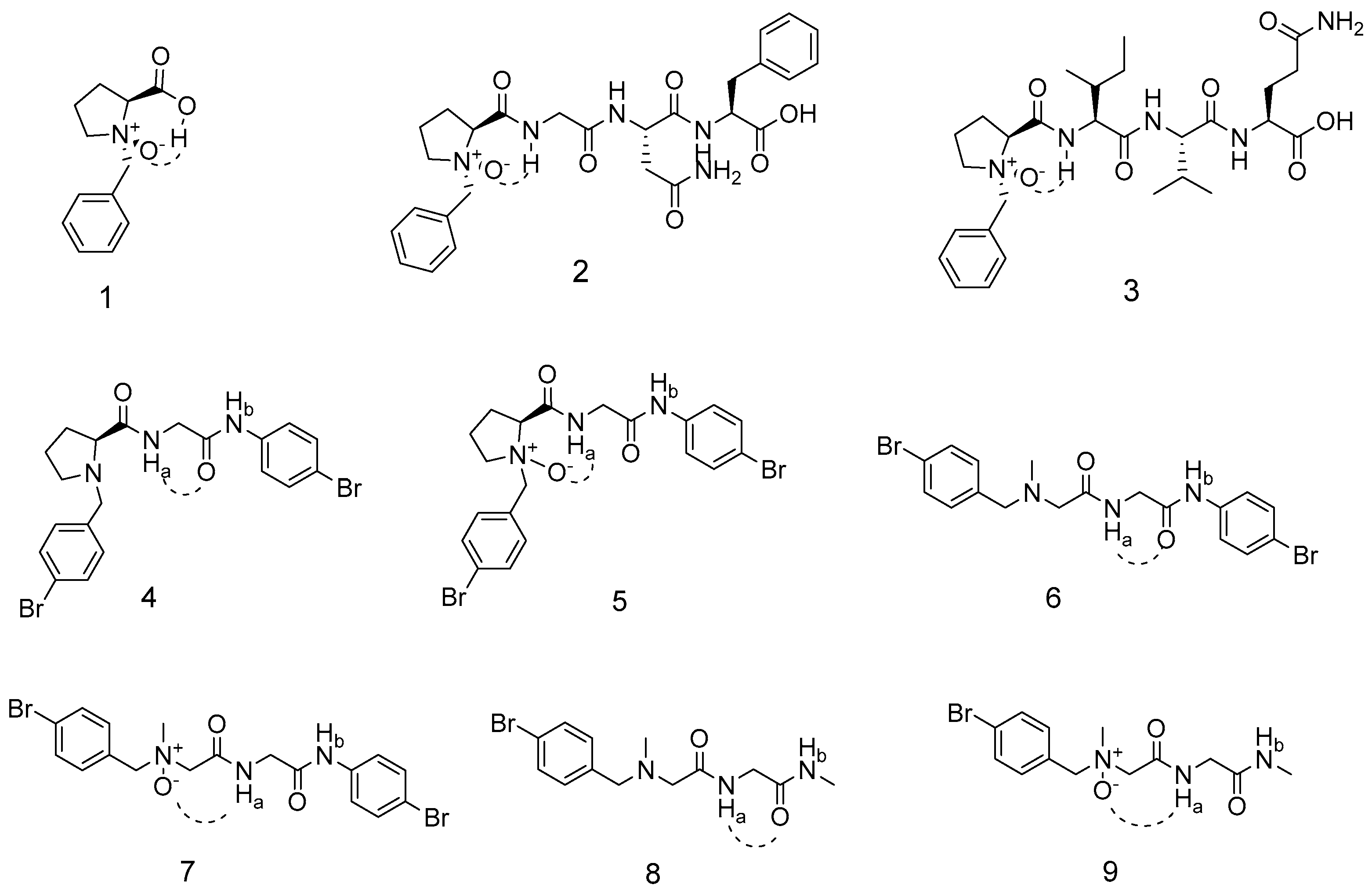

2. Results and Discussion

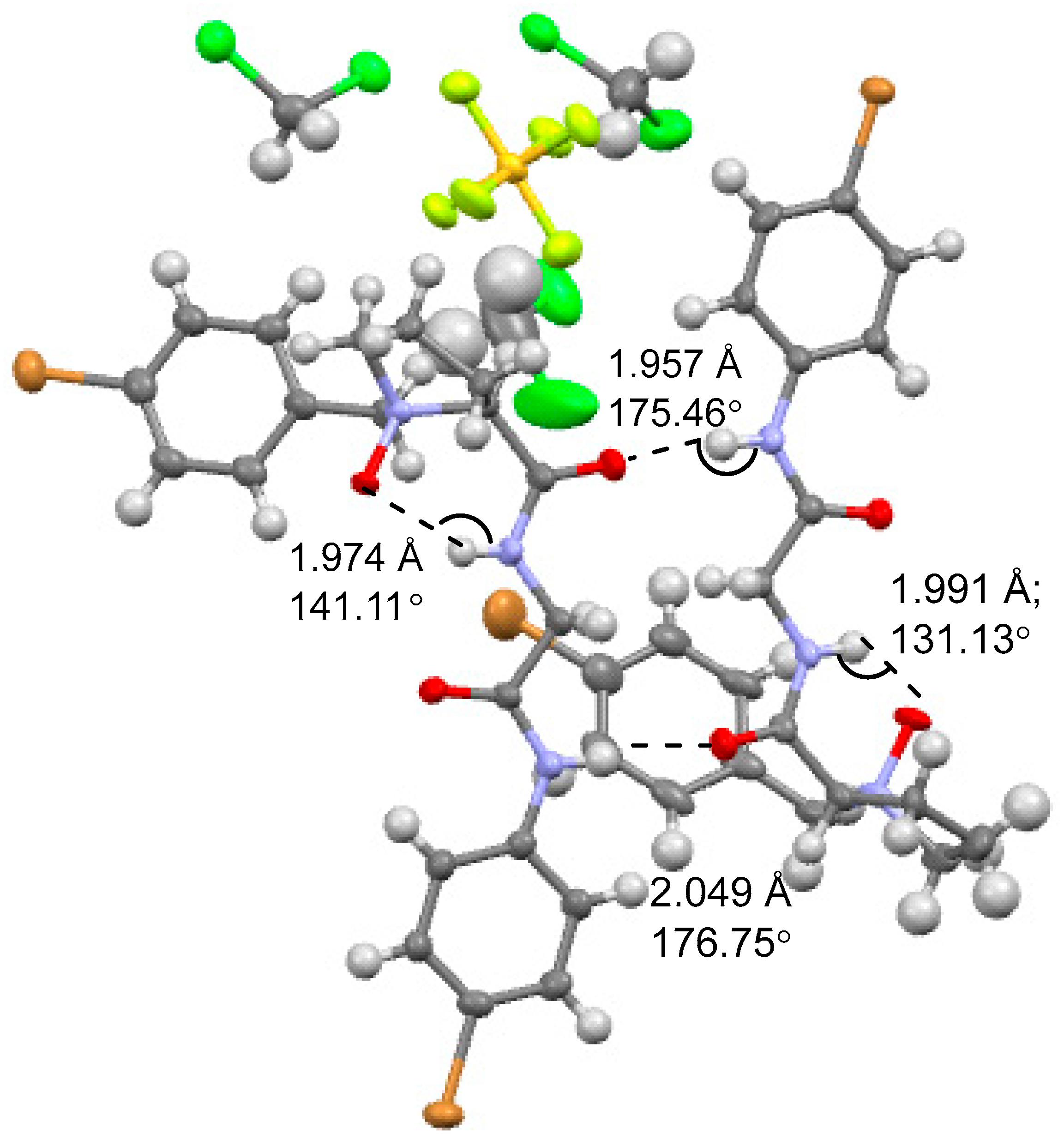

2.1. Crystal Structure of NOP 5

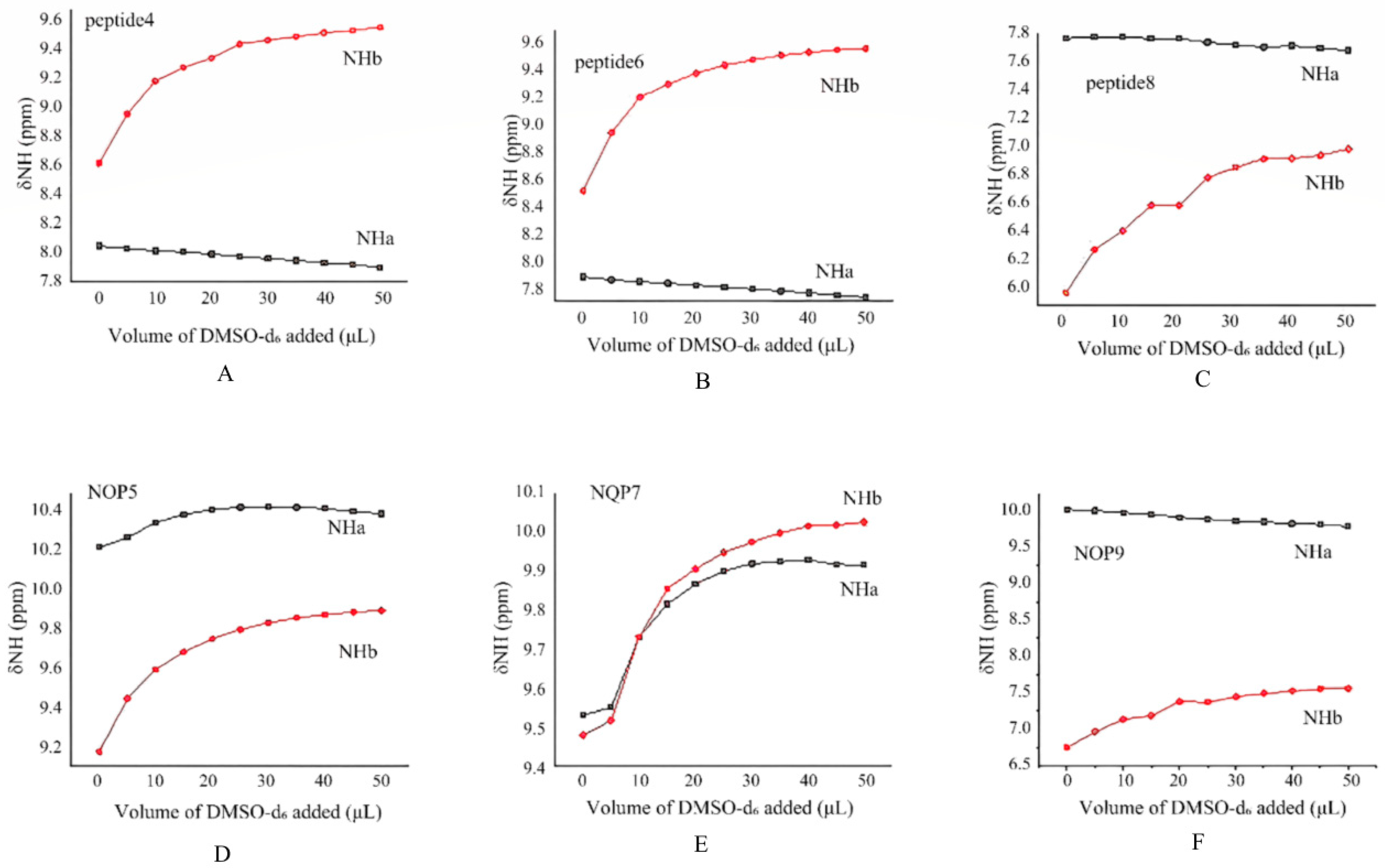

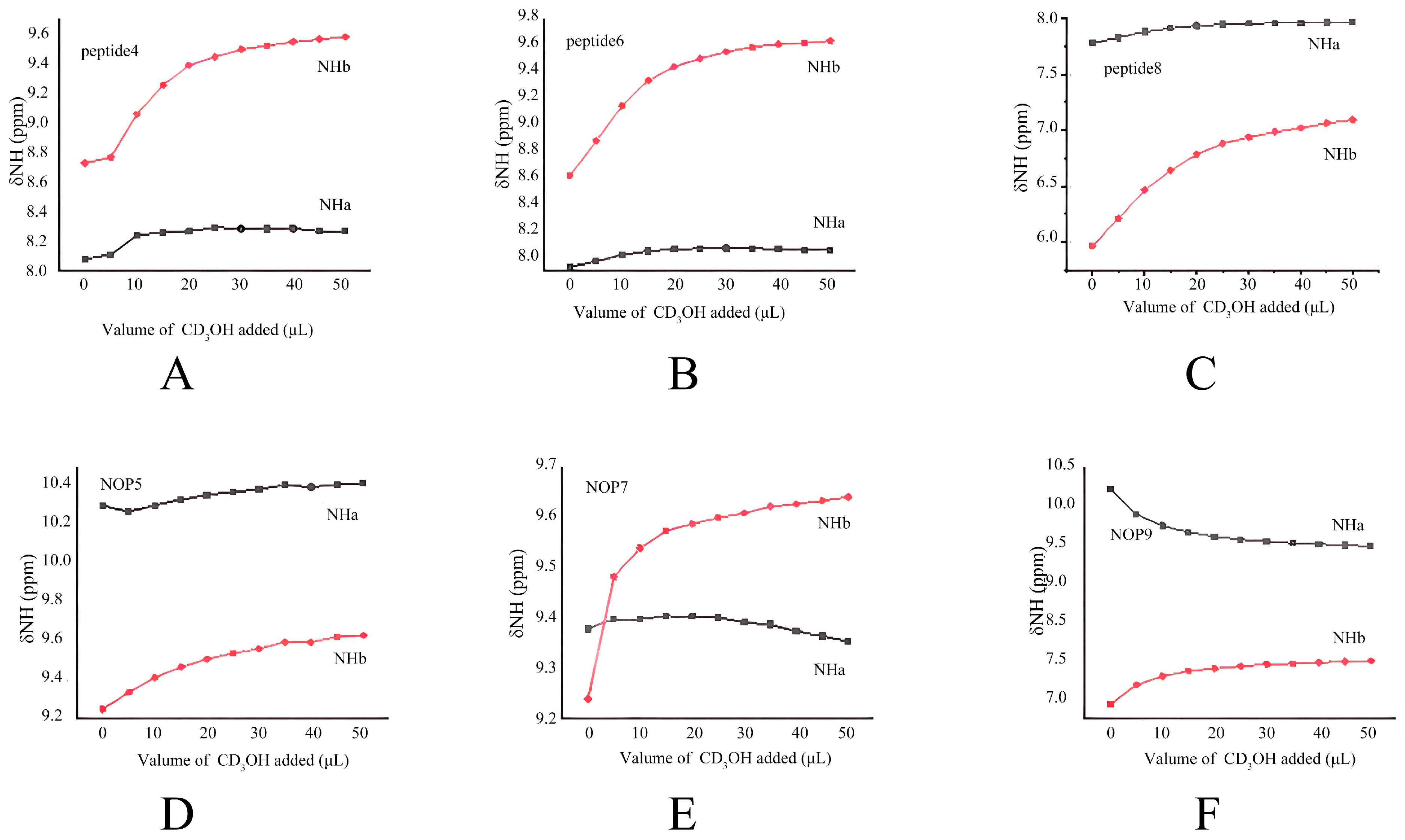

2.2. Hydrogen-Bond Existence in Solution

2.2.1. DMSO-d6 Titration Studies

2.2.2. CD3OH Titration Studies

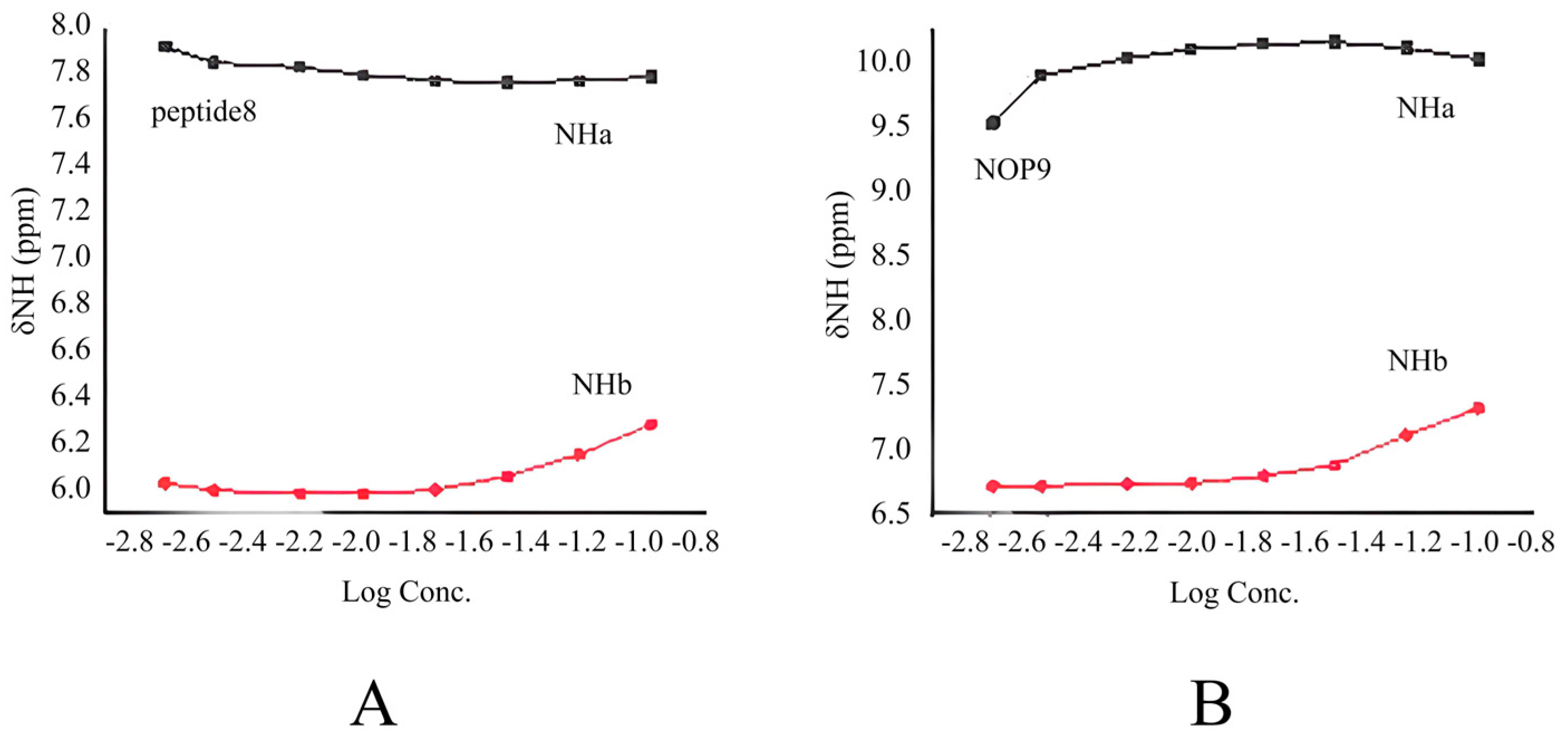

2.2.3. Concentration-Dependent Studies

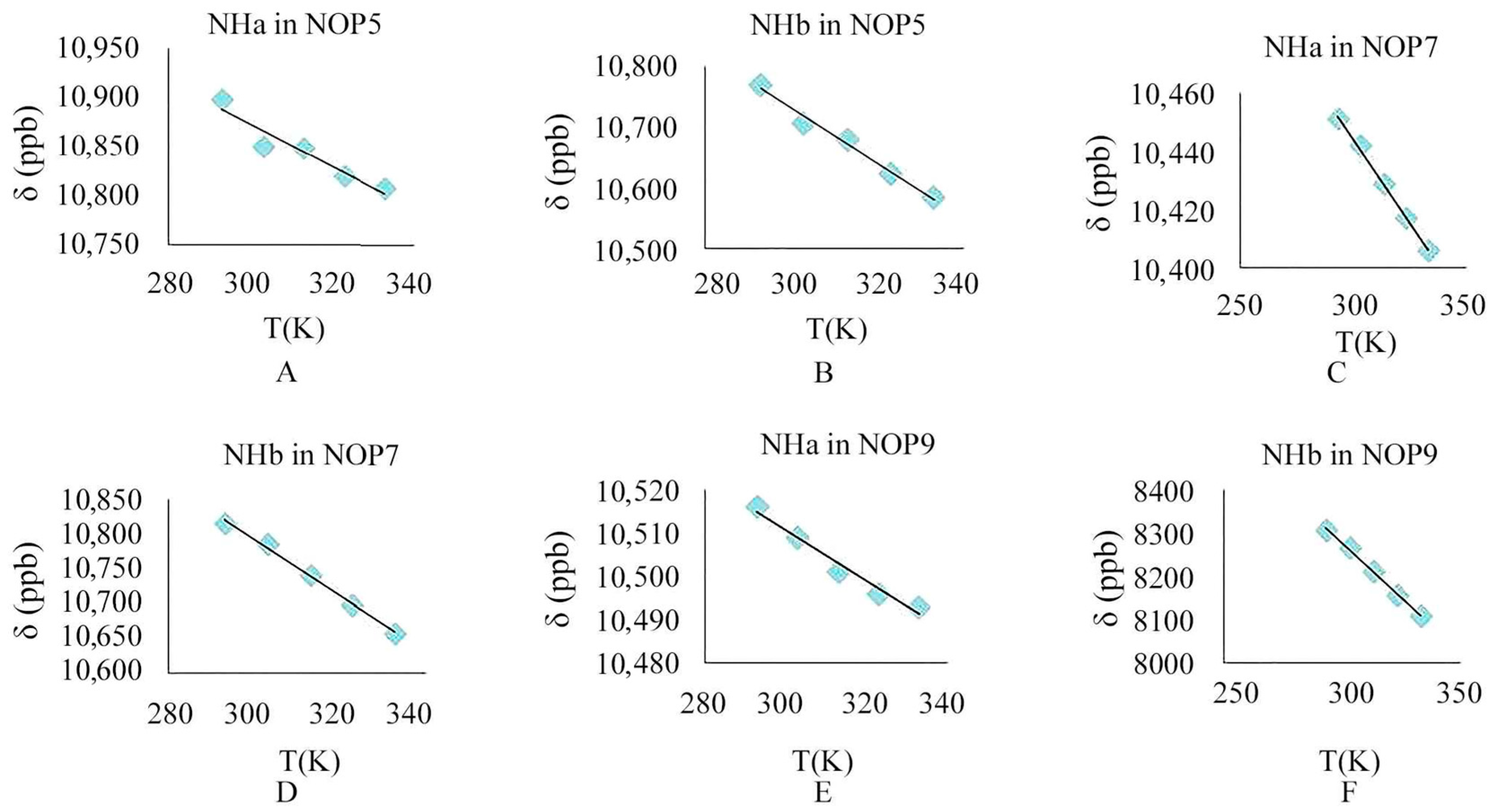

2.2.4. Variable Temperature Nuclear Magnetic Experiment

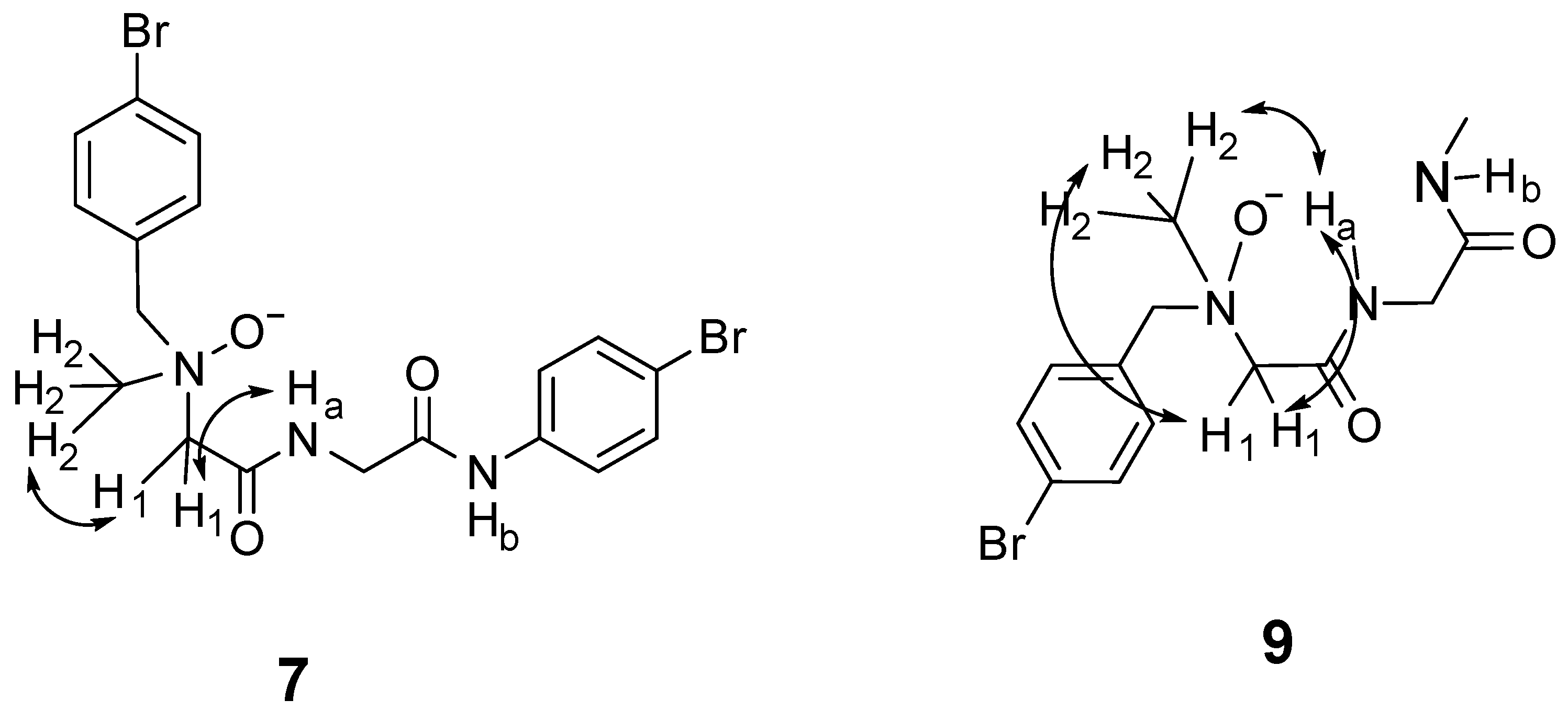

2.3. Nuclear Overhauser Effects (NOEs) of Dipeptides 7 and 9

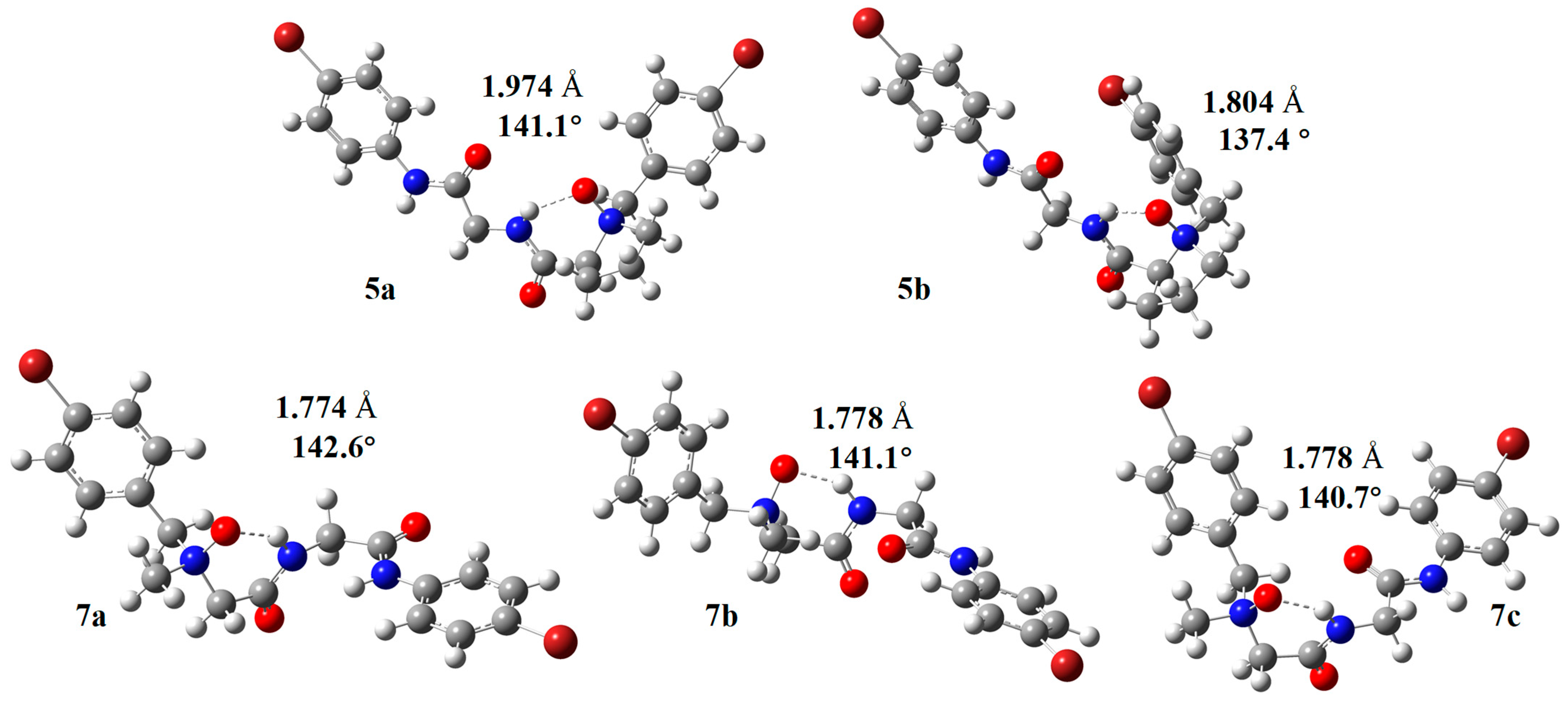

2.4. Computational Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemistry

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction

3.3. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Richardson, J.S. The Anatomy and Taxonomy of Protein Structure. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1981; Volume 34, pp. 167–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, G.L.; Bolin, D.R.; Bonner, M.P.; Bos, M.; Cook, C.M.; Fry, D.C.; Graves, B.J.; Hatada, M.; Hill, D.E. Concepts and Progress in the Development of Peptide Mimetics. J. Med. Chem. 1993, 36, 3039–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R.P.; Gellman, S.H.; DeGrado, W.F. β-Peptides: From Structure to Function. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3219–3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.-D.; Wang, D.-P. Theoretical Study on Side-Chain Control of the 14-Helix and the 10/12-Helix of β-Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 9352–9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Song, K.-S.; Wu, Y.-D.; Yang, D. Synthesis and Conformational Studies of γ−Aminoxy Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnowski, M.P.; Kang, C.W.; Elbatrawi, Y.M.; Wojtas, L.; Del Valle, J.R. Peptide N-Amination Supports β-Sheet Conformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2083–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, G.D.; Glerasch, L.M.; Smith, J.A. Turns in Peptides and Proteins. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985; Volume 37, pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Li, B.; Zhang, D.-W.; Chan, J.C.-Y.; Zhu, N.-Y.; Luo, S.-W.; Wu, Y.-D. Effect of Side Chains on Turns and Helices in Peptides of β3 -Aminoxy Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6956–6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appella, D.H.; Christianson, L.A.; Klein, D.A.; Powell, D.R.; Huang, X.; Barchi, J.J.; Gellman, S.H. Residue-Based Control of Helix Shape in β-Peptide Oligomers. Nature 1997, 387, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M.; Sukopp, M.; Tsomaia, N.; John, M.; Mierke, D.F.; Reif, B.; Kessler, H. The Conformation of Cyclo (− d -Pro−Ala4 −) as a Model for Cyclic Pentapeptides of the d L4 Type. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13806–13814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gademann, K.; Ernst, M.; Hoyer, D.; Seebach, D. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of a Cyclo-Tetrapeptide as a Somatostatin Analogue. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 1223–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezierska, A.; Panek, J.J.; Błaziak, K.; Raczyński, K.; Koll, A. Exploring Intra- and Intermolecular Interactions in Selected N-Oxides—The Role of Hydrogen Bonds. Molecules 2022, 27, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.; Wu, J.; Dai, W.-M. Synthesis of 5-Alkyl-5-Aryl-1-Pyrroline N-Oxides from 1-Aryl-Substituted Nitroalkanes and Acrolein via Michael Addition and Nitro Reductive Cyclization. Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 6384–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Long, X.; Zhang, C. Influence of N-Oxide Introduction on the Stability of Nitrogen-Rich Heteroaromatic Rings: A Quantum Chemical Study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 9446–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, K.; Veenus Seelan, T.; Lalitha, K.G.; Perumal, P.T. Synthesis and Antinociceptive Activity of Pyrazolyl Isoxazolines and Pyrazolyl Isoxazoles. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 3370–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, T.C.; Krasnykh, V.; Falany, C.N. Bacterial Expression and Kinetic Characterization of the Human Monoamine-Sulfating Form of Phenol Sulfotransferase. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995, 23, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitz, S. A Critical Appraisal of the NXY-059 Neuroprotection Studies for Acute Stroke: A Need for More Rigorous Testing of Neuroprotective Agents in Animal Models of Stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2007, 205, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryan, G.; Nilsen, A.; Braslau, R. Ketone Functionalized Nitroxides: Synthesis, Evaluation of N -Alkoxyamine Initiators, and Derivatization of Polymer Termini. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 7848–7854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenske, E.H.; Davison, E.C.; Forbes, I.T.; Warner, J.A.; Smith, A.L.; Holmes, A.B.; Houk, K.N. Reverse Cope Elimination of Hydroxylamines and Alkenes or Alkynes: Theoretical Investigation of Tether Length and Substituent Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2434–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer-Stenner, R.; Measey, T.J. The Alanine-Rich XAO Peptide Adopts a Heterogeneous Population, Including Turn-like and Polyproline II Conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6649–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, I.A.; Miller, N.D.; Peake, J.; Barkley, J.V.; Low, C.M.R.; Kalindjian, S.B. The Novel Use of Proline Derived Amine Oxides in Controlling Amide Conformation. Synlett 1993, 1993, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, I.A.; Miller, N.D.; Barkley, J.V.; Low, C.M.R.; Kalindjian, S.B. Homochiral Proline N-Oxides as Conformational Constraints in Peptide Like Molecules. Synlett 1995, 1995, 619–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, M.D.; Honarparvar, B.; Albericio, F.; Maguire, G.E.M.; Govender, T.; Arvidsson, P.I.; Kruger, H.G. Proline N-Oxides: Modulators of the 3D Conformation of Linear Peptides Through “NO-Turns”. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T. A Comprehensive Electron Wavefunction Analysis Toolbox for Chemists, Multiwfn. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 161, 082503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A Complete Structure Solution, Refinement and Analysis Program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatinus, L.; Van Der Lee, A. Symmetry Determination Following Structure Solution in P 1. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palatinus, L.; Prathapa, S.J.; Van Smaalen, S. EDMA: A Computer Program for Topological Analysis of Discrete Electron Densities. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated Space-Group and Crystal-Structure Determination. Acta Crystallogr. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, X.; Hui, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, W.; Lin, L.; Feng, X. Catalytic Asymmetric Bromoamination of Chalcones: Highly Efficient Synthesis of Chiral α-Bromo-β-Amino Ketone Derivatives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6160–6164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, A.J.; Neuhold, J.; Drescher, M.; Lemouzy, S.; González, L.; Maulide, N. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding in Conformationally Semi-Rigid α-Acylmethane Derivatives: A Theoretical NMR Study. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 7572–7579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, R.; Zhao, W.; Yuan, S.; Wang, T.; Lu, W.; Meng, Q.; Yang, L.; Sun, D. Proline-Free Local Turn via N-Oxidation: Crystallographic and Solution Evidence for a Six-Membered N–O⋯H–N Ring. Molecules 2025, 30, 4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244676

Zheng R, Zhao W, Yuan S, Wang T, Lu W, Meng Q, Yang L, Sun D. Proline-Free Local Turn via N-Oxidation: Crystallographic and Solution Evidence for a Six-Membered N–O⋯H–N Ring. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244676

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Renlin, Wenjiao Zhao, Shuo Yuan, Tong Wang, Wenyu Lu, Qian Meng, Li Yang, and Dequn Sun. 2025. "Proline-Free Local Turn via N-Oxidation: Crystallographic and Solution Evidence for a Six-Membered N–O⋯H–N Ring" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244676

APA StyleZheng, R., Zhao, W., Yuan, S., Wang, T., Lu, W., Meng, Q., Yang, L., & Sun, D. (2025). Proline-Free Local Turn via N-Oxidation: Crystallographic and Solution Evidence for a Six-Membered N–O⋯H–N Ring. Molecules, 30(24), 4676. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244676