Insight into the Molecular and Structural Changes in Red Pepper Induced by Direct and Indirect Ultrasonic Treatments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

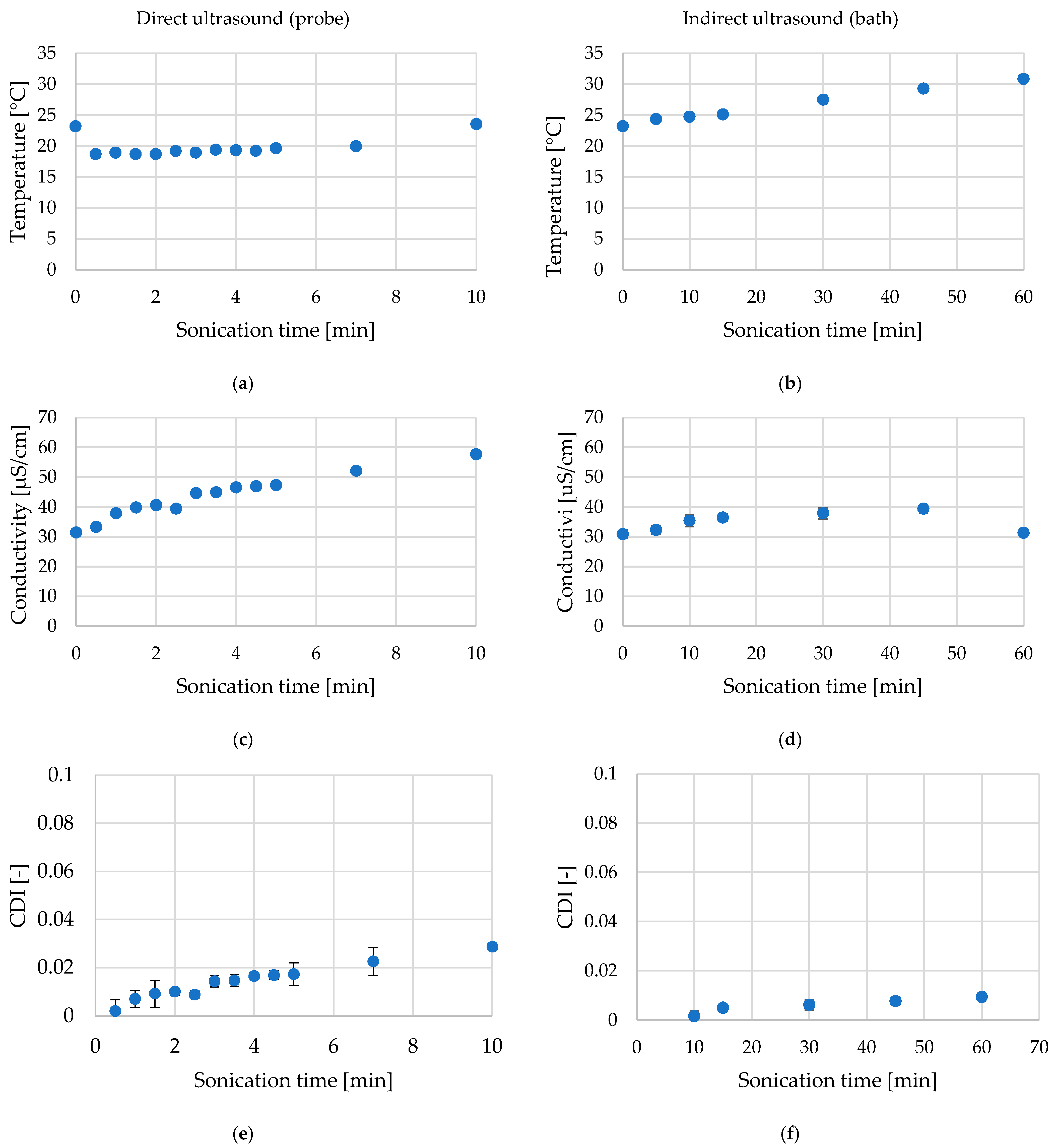

2.1. Temperature, Conductivity, and Cell Disintergration Index (CDI) During Ultrasound Treatment of Red Bell Pepper

2.2. Physical Quality Attributes (Color and Texture)

2.3. Microbiological Quality

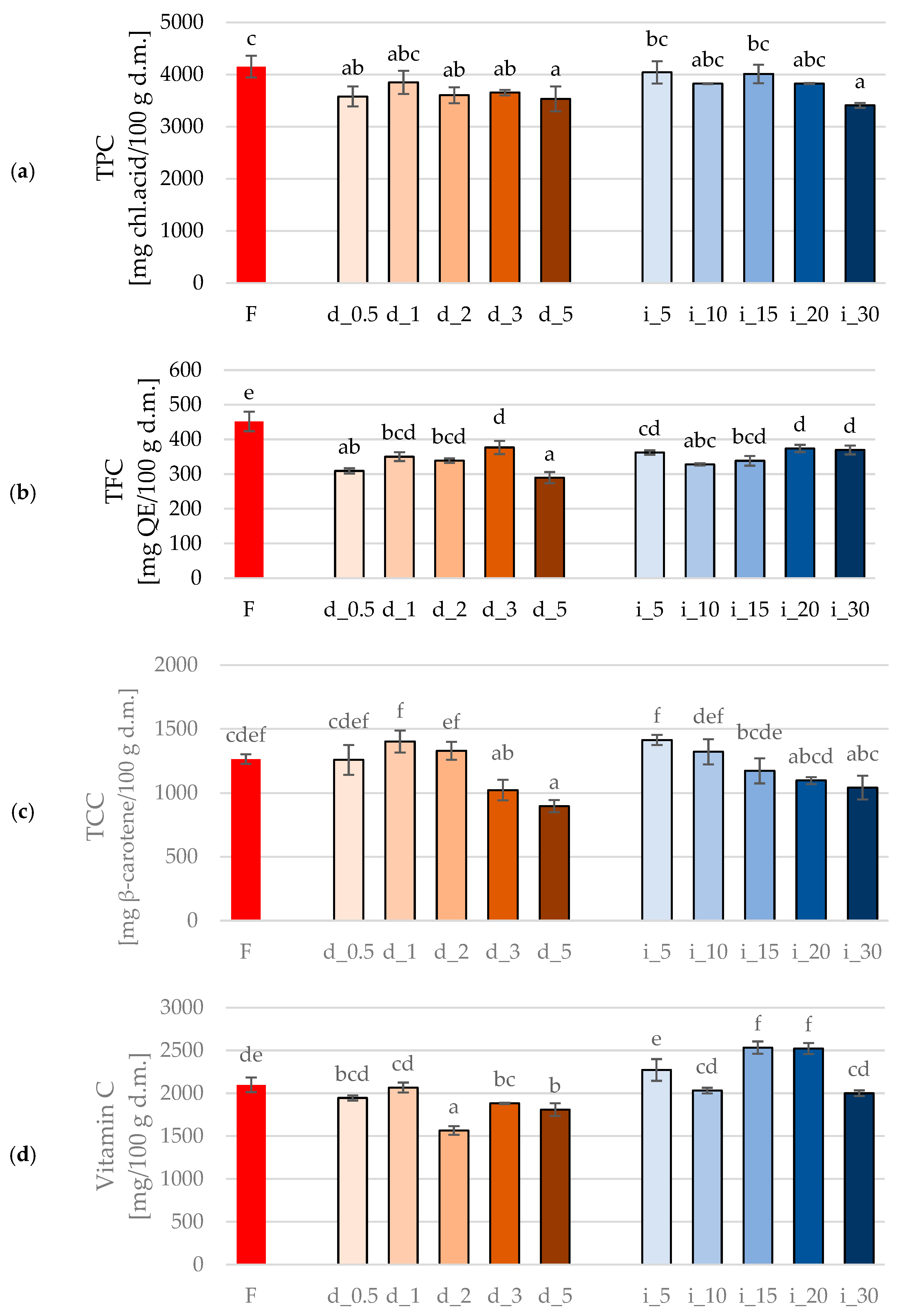

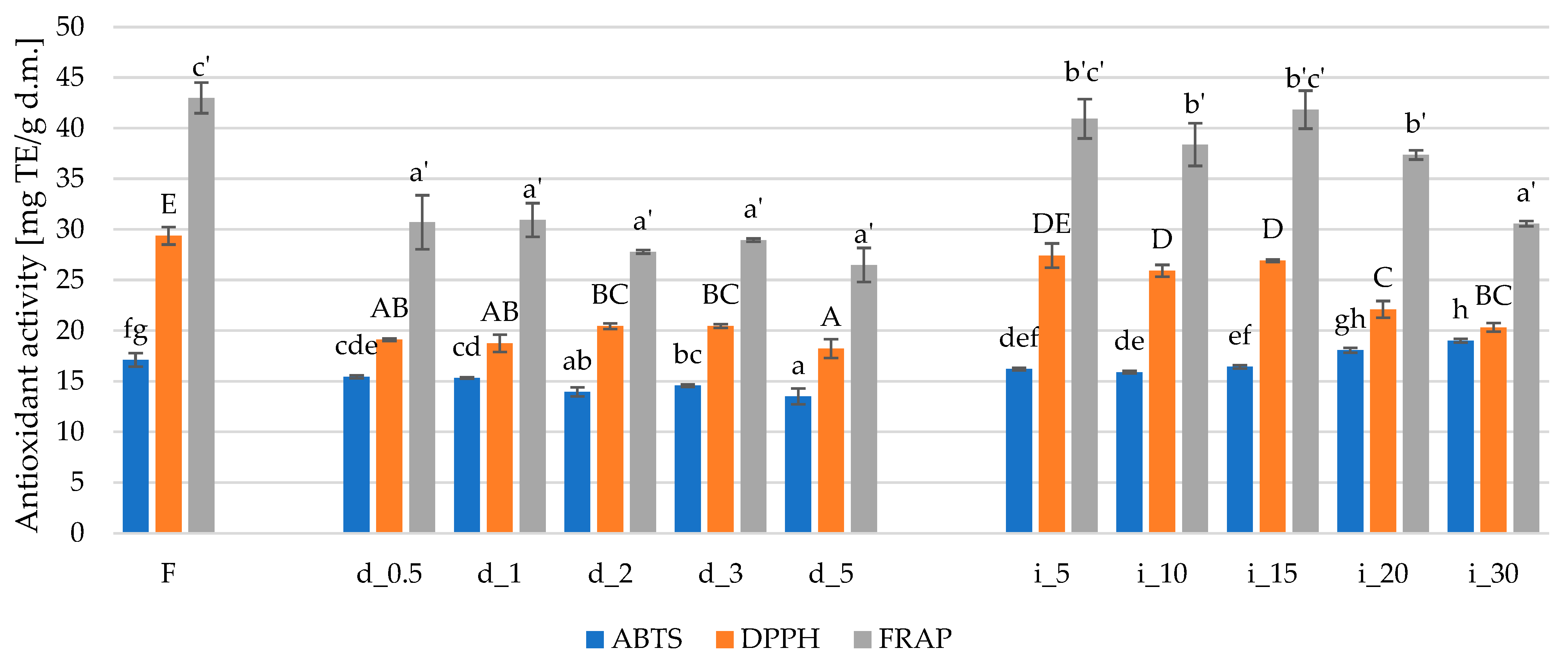

2.4. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

2.4.1. Bioactive Compounds (Total Polyphenols Content (TPC), Total Flavonoid Content (TFC), Total Carotenoid Content (TCC), Vitamin C Content) of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

2.4.2. Antioxidant Activity of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

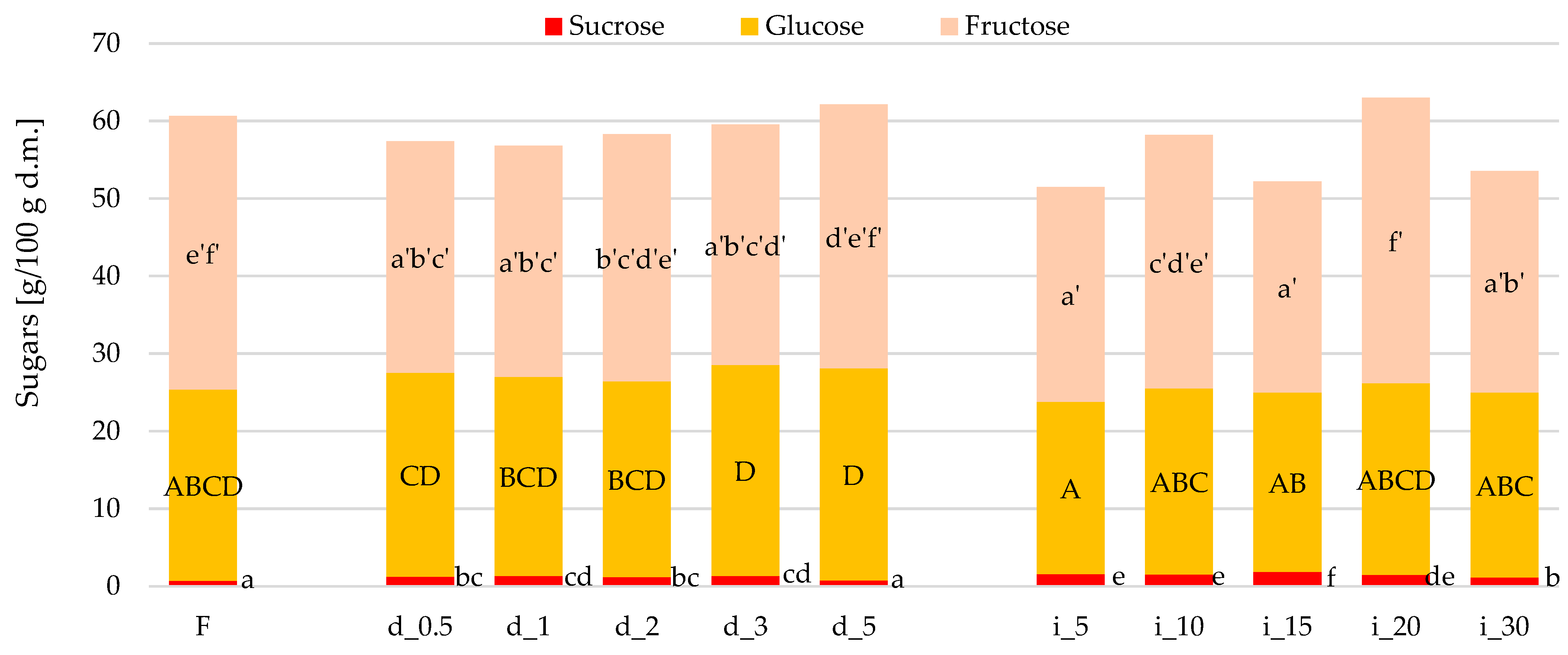

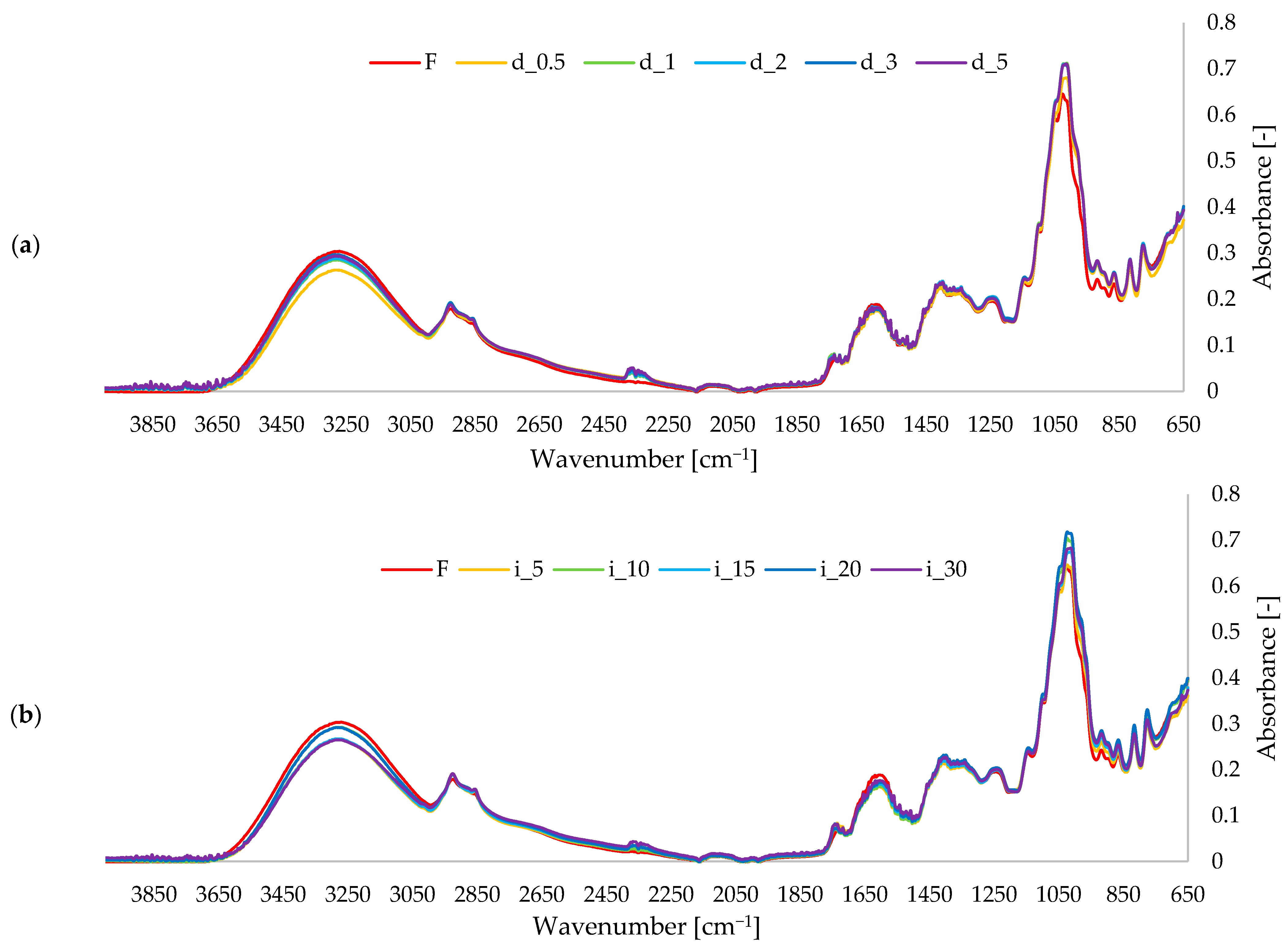

2.5. Sugars and Molecular Profile

2.5.1. Sugars (Sucrose, Glucose, Fructose) Content in Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

2.5.2. FTIR Spectra of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

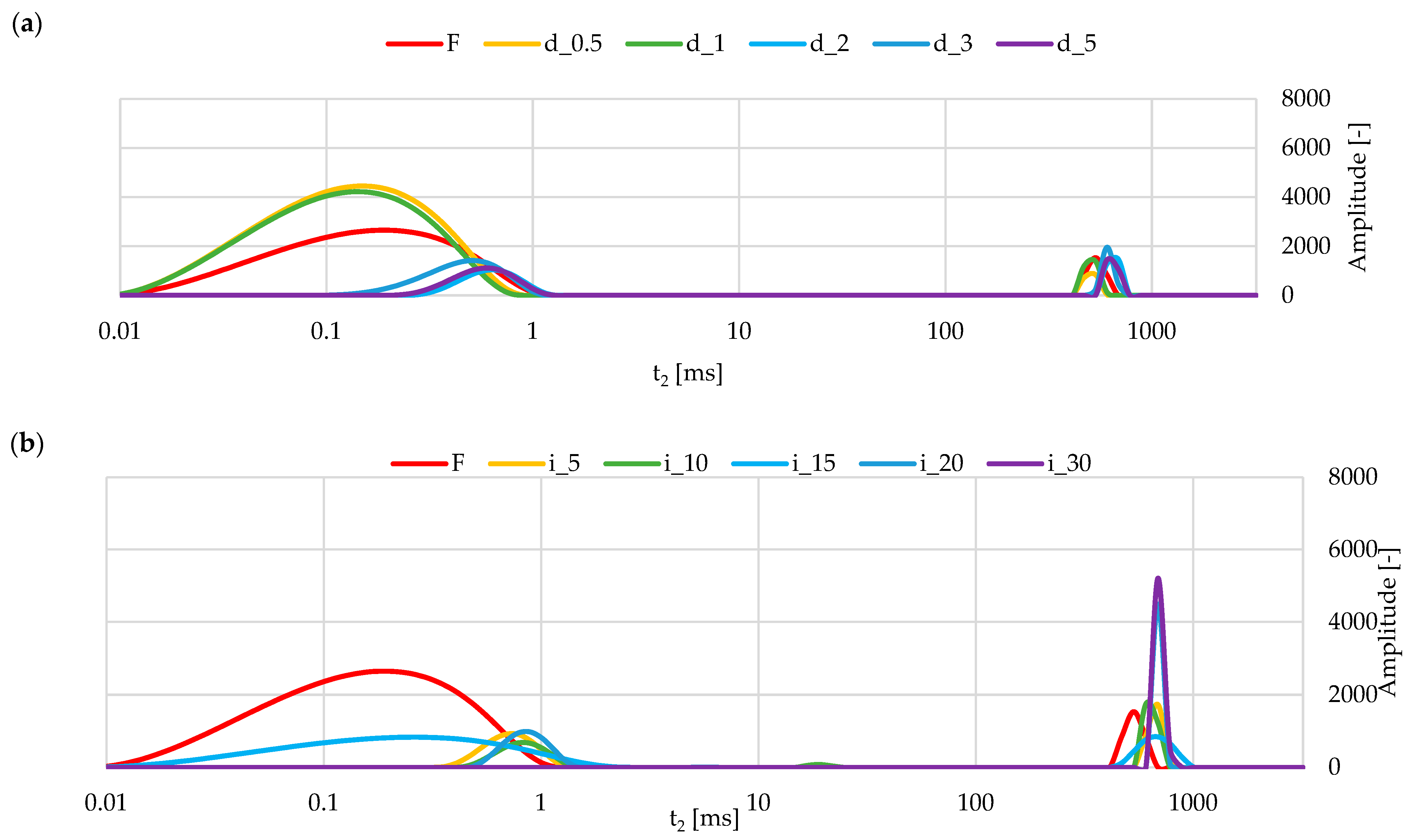

2.5.3. NMR of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

2.6. Thermal and Structural Characteristics

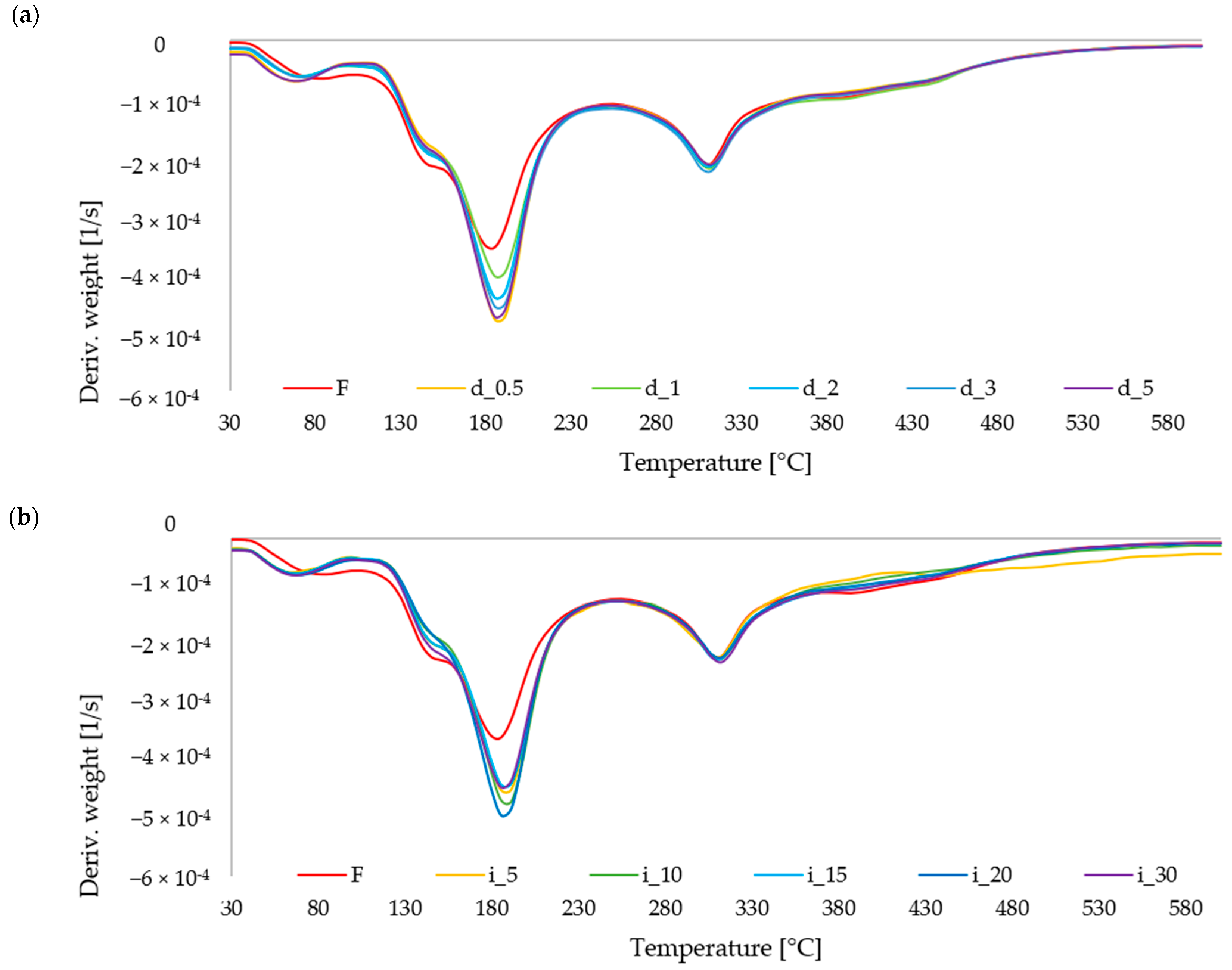

2.6.1. TGA of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound

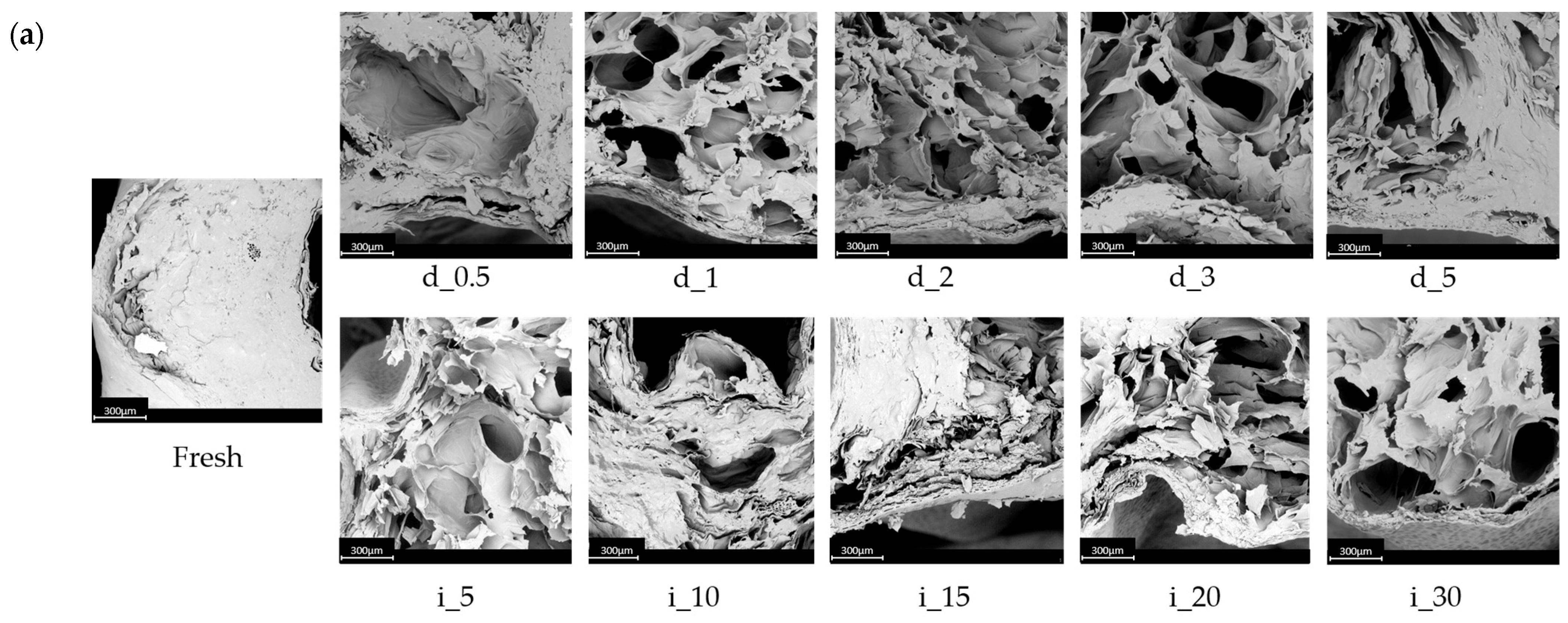

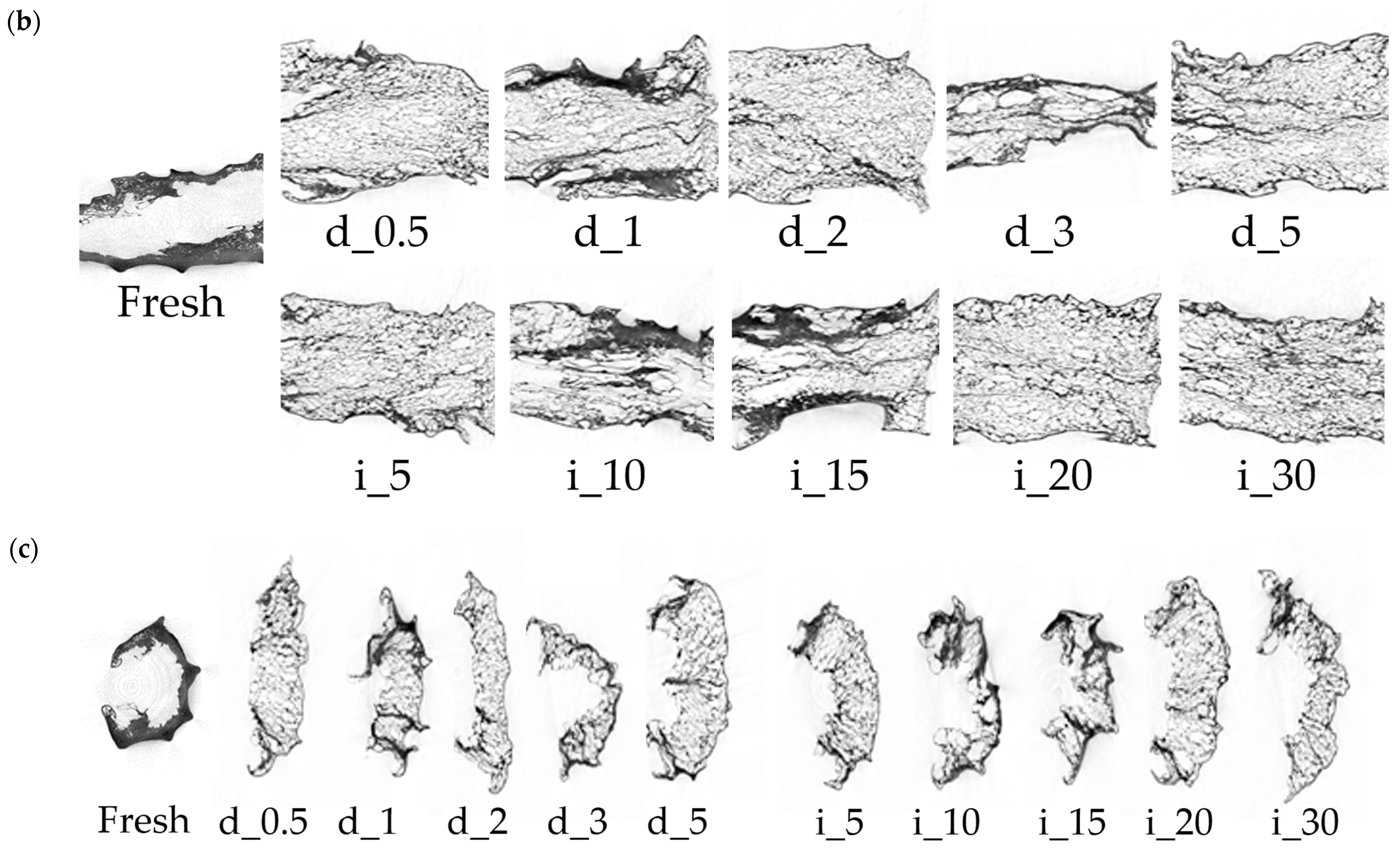

2.6.2. Structural Changes of Red Bell Pepper Treated with Direct and Indirect Ultrasound Evaluated on the Basis of SEM and Micro-CT

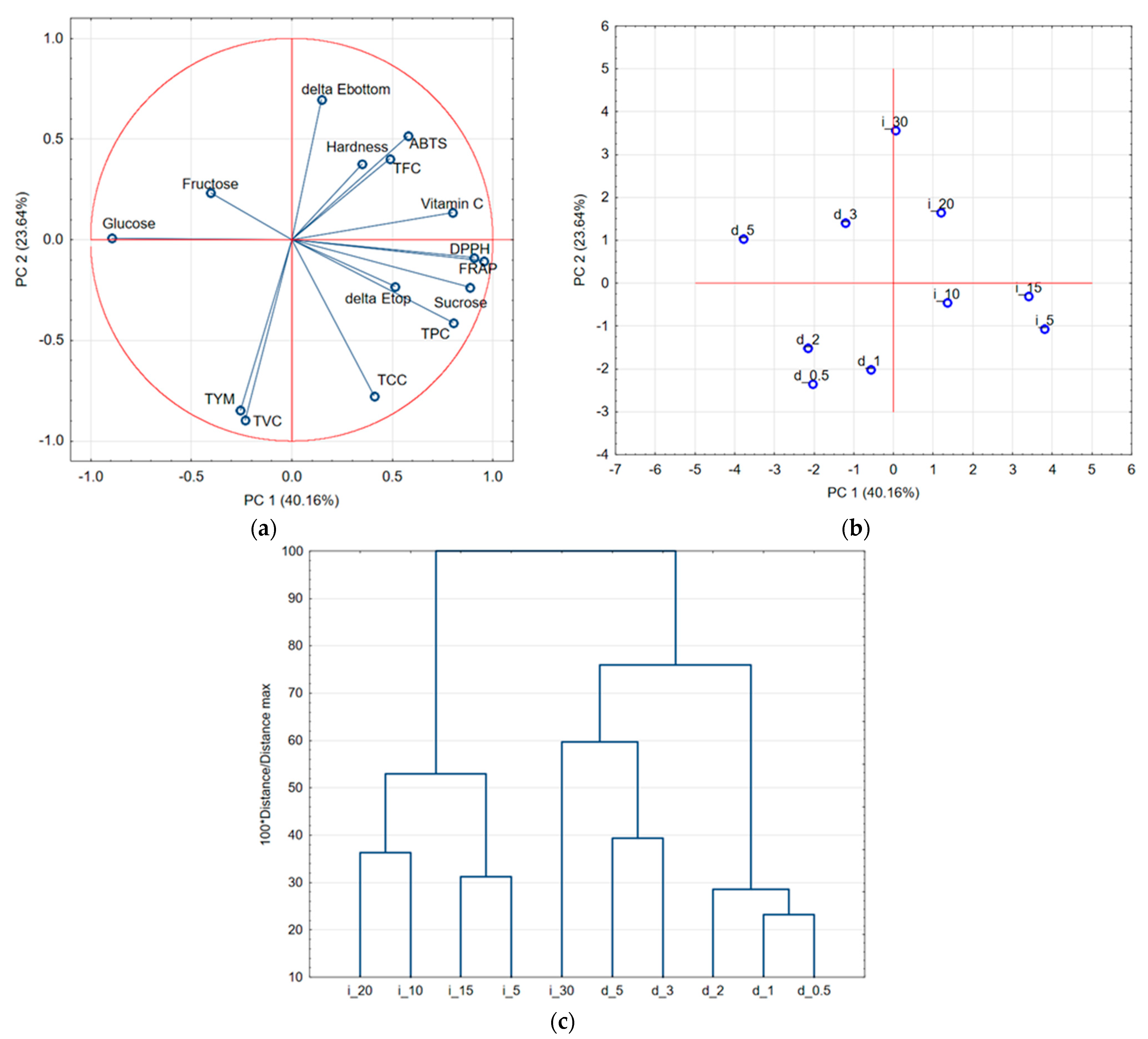

2.7. Overall Impact of Ultrasound Type on Red Bell Pepper Tissue

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

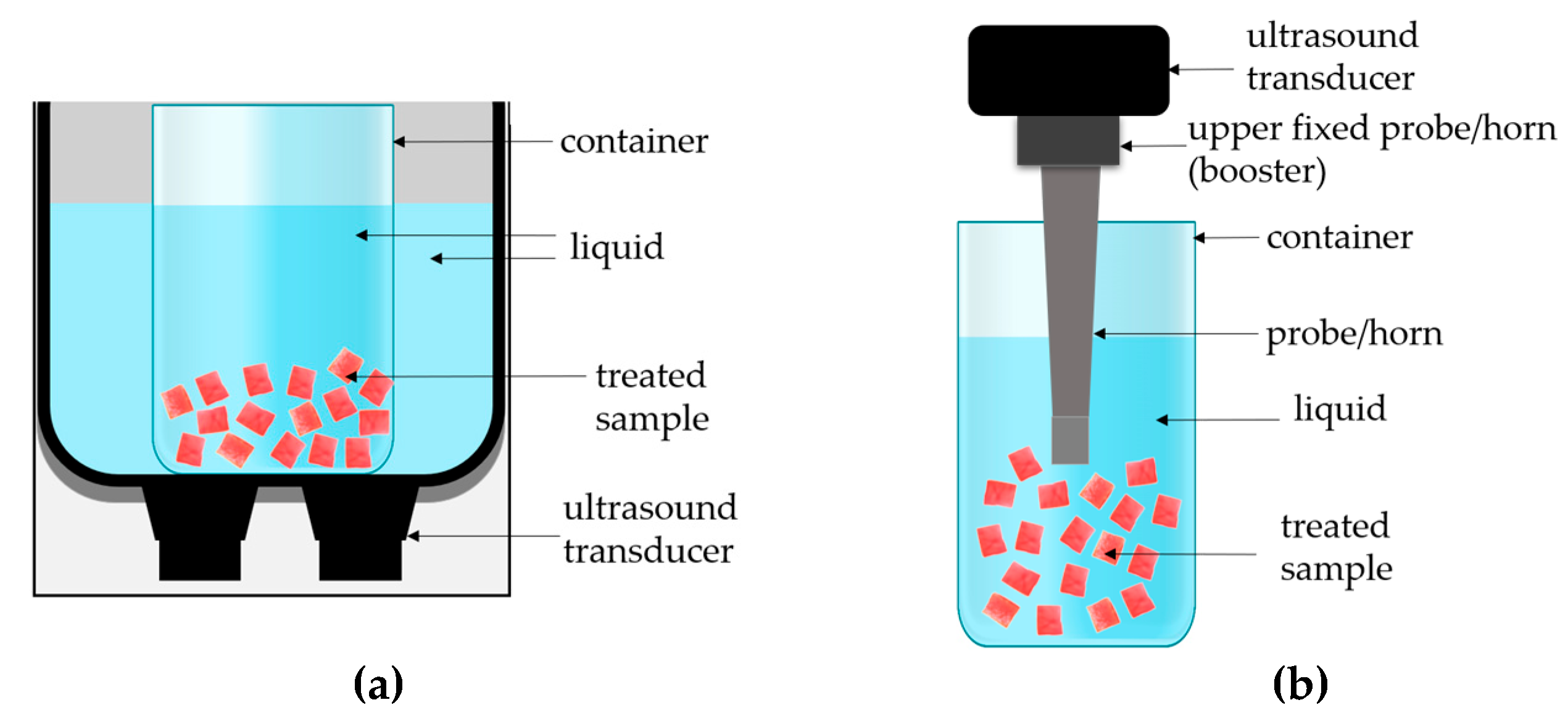

3.2. Ultrasonic Treatment

3.2.1. Indirect Sonication (Ultrasonic Bath System)

3.2.2. Direct Sonication (Ultrasonic Probe System)

- Direct ultrasound treatment (probe system): d_0.5, d_1, d_2, d_3, and d_5 (0.5–5 min),

- Indirect ultrasound treatment (bath system): i_5, i_10, i_15, i_20, and i_30 (5–30 min),

- The fresh (untreated) sample (F) was used as a control in all comparative analyses.

3.3. Research Methods

3.3.1. Color

3.3.2. Texture

3.3.3. Water State in Samples

3.3.4. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

3.3.5. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

3.3.6. Total Carotenoid Content (TCC)

3.3.7. Vitamin C Content

3.3.8. Antioxidant Activity (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP)

3.3.9. Sugar Content

3.3.10. FTIR

3.3.11. TGA

3.3.12. Microbial Analysis

3.3.13. SEM and Microtomography

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Mora, Z.V.-d.l.; Vázquez-Paulino, O.; Ascencio, F.; Villarruel-López, A. Bell Peppers (Capsicum annum L.) Losses and Wastes: Source for Food and Pharmaceutical Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanatombi, K. Antioxidant potential and factors influencing the content of antioxidant compounds of pepper: A review with current knowledge. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3011–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanatombi, K. A comprehensive review on sustainable strategies for valorization of pepper waste and their potential application. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oboh, G.; Rocha, J.B.T. Polyphenols in red pepper [Capsicum annuum var. aviculare (Tepin)] and their protective effect on some pro-oxidants induced lipid peroxidation in brain and liver. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 225, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Cao, Y. Influence of ultrasonic pretreatment on the quality attributes and pectin structure of chili peppers (Capsicum spp.). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 110, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, K.; Wiktor, A.; Kaveh, M.; Dadan, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Effect of Thermal and Non-Thermal Technologies on Kinetics and the Main Quality Parameters of Red Bell Pepper Dried with Convective and Microwave–Convective Methods. Molecules 2022, 27, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kek, S.P.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A. Direct and indirect power ultrasound assisted pre-osmotic treatments in convective drying of guava slices. Food Bioprod. Process. 2013, 91, 495–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadan, M.; Wiktor, A.; Rybak, K.; Kamińska-Dwórznicka, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Insights into the mechanisms of ultrasound treatment on plant tissue as revealed by TD-NMR, microstructural analysis, and electrical properties measurements. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 104, 104116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prempeh, N.Y.A.; Nunekpeku, X.; Murugesan, A.; Li, H. Ultrasound in the Food Industry: Mechanisms and Applications for Non-Invasive Texture and Quality Analysis. Foods 2025, 14, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadan, M.; Nowacka, M.; Wiktor, A.; Sobczynska, A.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Ultrasound to improve drying processes and prevent thermolabile nutrients degradation. In Design and Optimization of Innovative Food Processing Techniques Assisted by Ultrasound; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 55–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kentish, S.; Ashokkumar, M. The Physical and Chemical Effects of Ultrasound. In Ultrasound Technologies for Food and Bioprocessing; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacka, M.; Dadan, M. Ultrasound-Assisted Drying of Food. In Emerging Food Processing Technologies; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C.; Niu, P.; Ren, X.; Zhou, J.; Lai, Y.; Wang, P. Effects of ultrasonic pretreatment combined with vacuum drying on the drying kinetics and quality of green peppers. LWT 2025, 231, 118351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiselvam, R.; Aydar, A.Y.; Kutlu, N.; Aslam, R.; Sahni, P.; Mitharwal, S.; Gavahian, M.; Kumar, M.; Raposo, A.; Yoo, S.; et al. Individual and interactive effect of ultrasound pre-treatment on drying kinetics and biochemical qualities of food: A critical review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 92, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumcuoglu, S.; Yilmaz, T.; Tavman, S. Ultrasound assisted extraction of lycopene from tomato processing wastes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 4102–4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Cakmak, H.; Tavman, S. Ultrasonic pretreatment of carrot slices: Effects of sonication source on drying kinetics and product quality. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2019, 91, e20180447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, L.; Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Martínez-Zamora, L.; Zapata, R.; Artés-Hernández, F. Effect of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction with Probe or Bath on Total Phenolics from Tomato and Lemon By-Products. In Proceedings of the The 4th International Electronic Conference on Foods 2023, Online, 15–30 October 2023; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2023; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Belgheisi, S.; EsmaeilZadeh Kenari, R. Improving the qualitative indicators of apple juice by Chitosan and ultrasound. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambrak, A.R.; Mason, T.J.; Paniwnyk, L.; Lelas, V. Ultrasonic effect on pH, electric conductivity, and tissue surface of button mushrooms, Brussels sprouts and cauliflower. Czech J. Food Sci. 2007, 25, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lučić, M.; Potkonjak, N.; Sredović Ignjatović, I.; Lević, S.; Dajić-Stevanović, Z.; Kolašinac, S.; Belović, M.; Torbica, A.; Zlatanović, I.; Pavlović, V.; et al. Influence of Ultrasonic and Chemical Pretreatments on Quality Attributes of Dried Pepper (Capsicum annuum). Foods 2023, 12, 2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, S.; Radi, M.; Hosseinifarahi, M.; Amiri, S. Microbial and physicochemical changes in green bell peppers treated with ultrasonic-assisted washing in combination with Thymus vulgaris essential oil nanocapsules. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amal Sudaraka Samarasinghe, H.G.; Dharmaprema, S.; Manodya, U.; Kariyawasam, K.P.; Samaranayake, U.C. Exploring Impact of the Ultrasound and Combined Treatments on Food Quality: A Comprehensive Review. Turkish J. Agric.—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña, M.; Calahorro, M.; Eim, V.; Rosselló, C.; Simal, S. Measurement of microstructural changes promoted by ultrasound application on plant materials with different porosity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 88, 106087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Sun, G.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, Q.; Tang, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Effects of ultrasonic and high-pressure processing pretreatment on drying characteristics and quality attributes of Angelica keiskei slices prepared by vacuum-freeze drying. LWT 2025, 225, 117901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, K.; Wu, J.; Chen, L. Ultrasound and its combined application in the improvement of microbial and physicochemical quality of fruits and vegetables: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 80, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Salazar, J.K.; Fay, M.L.; Zhang, W. Efficacy of Power Ultrasound-Based Hurdle Technology on the Reduction of Bacterial Pathogens on Fresh Produce. Foods 2023, 12, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenyorege, E.A.; Ma, H.; Ayim, I.; Zhou, C. Ultrasound decontamination of pesticides and microorganisms in fruits and vegetables: A review. J. Food Saf. Food Qual. 2018, 69, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Macleod, J.; Blaxland, J. The Use of Ozone Technology to Control Microorganism Growth, Enhance Food Safety and Extend Shelf Life: A Promising Food Decontamination Technology. Foods 2023, 12, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvitz, S.; Cantalejo, M.J. Effects of ozone and chlorine postharvest treatments on quality of fresh—Cut red bell peppers. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodoni, L.M.; Zaro, M.J.; Hasperué, J.H.; Concellón, A.; Vicente, A.R. UV-C treatments extend the shelf life of fresh-cut peppers by delaying pectin solubilization and inducing local accumulation of phenolics. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. Influence of high-intensity ultrasound on bioactive compounds of strawberry juice: Profiles of ascorbic acid, phenolics, antioxidant activity and microstructure. Food Control 2019, 96, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutlu, N.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kamiloglu, A.; Saka, I.; Sruthi, N.U.; Kothakota, A.; Socol, C.T.; Maerescu, C.M. Impact of ultrasonication applications on color profile of foods. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 89, 106109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, D.-W. Kinetic modeling of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from grape marc: Influence of acoustic energy density and temperature. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, N.; Wang, D.; Fu, X.; Xie, H.; Gao, G.; Luo, Z. Green Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Lotus Seedpod (Receptaculum Nelumbinis) Assisted by Ultrasound Coupled with Glycerol. Foods 2021, 10, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.-T.; Deng, W.; Li, J.; Geng, J.-L.; Hu, Y.-C.; Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y. Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Thinned Young Kiwifruits and Their Beneficial Effects. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmadi, S.; Adoui, F.; Dumas, E.; Karoune, S.; Santerre, C.; Gharsallaoui, A. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from the Aerial Part of Plants in the Chenopodiaceae Family Using a Box–Behnken Design. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Pang, S.; Zhong, M.; Sun, Y.; Qayum, A.; Liu, Y.; Rashid, A.; Xu, B.; Liang, Q.; Ma, H.; et al. A comprehensive review of ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) for bioactive components: Principles, advantages, equipment, and combined technologies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 101, 106646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomšik, A.; Pavlić, B.; Vladić, J.; Ramić, M.; Brindza, J.; Vidović, S. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from wild garlic (Allium ursinum L.). Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 29, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiranpradith, V.; Therdthai, N.; Soontrunnarudrungsri, A.; Rungsuriyawiboon, O. Optimisation of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Total Phenolics and Flavonoids Content from Centella asiatica. Foods 2025, 14, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Chitrakar, B.; Zhang, M. Effect of ultrasound pretreatment on physical, bioactive, and antioxidant properties of carrot cubes after centrifugal dewatering. Dry. Technol. 2021, 39, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawira-Atmaja, M.I.; Puangpraphant, S. Effects of ultrasound-assisted bath, probe, and extraction time on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in white tea (Camellia sinensis) extracts from purple- and green-leaf cultivars. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2025, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Ramos, M.J.; del Razola-Díaz, M.C.; Verardo, V.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M. Comparison between Ultrasonic Bath and Sonotrode Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Mango Peel By-Products. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, A.; Farid, M. Effect of Temperatures on Polyphenols during Extraction. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xia, W.; Shao, P.; Wu, W.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Mu, H.; Xiao, J.; Gao, H. Impact of thermal processing on dietary flavonoids. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 100915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedlińska, A.; Rybak, K.; Samborska, K.; Barańska-Dołomisiewicz, A.; Skarżyńska, A.; Trusińska, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. Hybrid Drying Method: Influence of Pre-Treatment and Process Conditions of Ultrasound-Assisted Drying on Apple Quality. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ying, X.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Shang, J.; Zang, Z.; Wan, F.; Huang, X. Evaluation of the Effect of Ultrasonic Pretreatment on the Drying Kinetics and Quality Characteristics of Codonopsis pilosula Slices Based on the Grey Correlation Method. Molecules 2023, 28, 5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Vanga, S.K.; Raghavan, V. High-intensity ultrasound processing of kiwifruit juice: Effects on the ascorbic acid, total phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidant capacity. LWT 2019, 107, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Liu, Y. Ozone Combined with Ultrasound Processing of High-Sugar Concentrated Orange Juice: Effects on the Antimicrobial Capacity, Antioxidant Activity, and In Vitro Bioaccessibility of Carotenoids. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 3046–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yu, Y.; Xie, F.; Gu, X.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z. High pressure homogenization versus ultrasound treatment of tomato juice: Effects on stability and in vitro bioaccessibility of carotenoids. LWT 2019, 116, 108597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Mohamadian, E.; Dadari, S.; Arbab, M.M.; Karimi, N. Application of high frequency ultrasound in different irradiation systems for photosynthesis pigment extraction from Chlorella microalgae. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2017, 34, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, A.T.; Wahia, H.; Ji, Q.; Fakayode, O.A.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C. Multiple—Frequency ultrasound for the inactivation of microorganisms on food: A review. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, T.R.; Vieira, P.; Silva, B.M.; Freitas, T.D.; do Amaral, A.J.B.; Vieira, E.N.R.; de Leite Júnior, B.R.C. What are the prospects for ultrasound technology in food processing? An update on the main effects on different food matrices, drawbacks, and applications. J. Food Process Eng. 2021, 44, e13872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, N.; Mor, R.S.; Kumar, K.; Sharanagat, V.S. Advances in application of ultrasound in food processing: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 70, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.S.M.; Babgi, B.; Alghamdi, Y.; Aksu, M.; Madhavan, J.; Ashokkumar, M. Physical and chemical effects of acoustic cavitation in selected ultrasonic cleaning applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2016, 29, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashokkumar, M. The characterization of acoustic cavitation bubbles—An overview. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingret, D.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Chemat, F. Degradation during application of ultrasound in food processing: A review. Food Control 2013, 31, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urango, A.C.M.; Strieder, M.M.; Silva, E.K.; Meireles, M.A.A. Impact of Thermosonication Processing on Food Quality and Safety: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1700–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Jiang, A. Effect of ultrasound treatment on quality and microbial load of carrot juice. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Cuéllar-Villarreal, M.R.; Ortega-Hernández, E.; Becerra-Moreno, A.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A. Effects of ultrasound treatment and storage time on the extractability and biosynthesis of nutraceuticals in carrot (Daucus carota). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 119, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Engeseth, N.J.; Feng, H. High Intensity Ultrasound as an Abiotic Elicitor—Effects on Antioxidant Capacity and Overall Quality of Romaine Lettuce. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2016, 9, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esua, O.J.; Chin, N.L.; Yusof, Y.A.; Sukor, R. Effects of simultaneous UV-C radiation and ultrasonic energy postharvest treatment on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of tomatoes during storage. Food Chem. 2019, 270, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ding, J.; Park, H.K.; Feng, H. High intensity ultrasound as a physical elicitor affects secondary metabolites and antioxidant capacity of tomato fruits. Food Control 2020, 113, 107176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound assisted extraction of food and natural products. Mechanisms, techniques, combinations, protocols and applications. A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M.; Abid, M.; Mumraiz, M.; Jabbar, S.; Xun, S.; Ameer, K.; Riaz Rajoka, M.S.; Zhendan, H.; Alotaibi, S.S.; Mugabi, R.; et al. Emerging frontiers in juice processing: The role of ultrasonication and other non-thermal technologies in enhancing antioxidant capacity and quality of fruit and vegetable juices. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 122, 107554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi Sadeer, N.; Montesano, D.; Albrizio, S.; Zengin, G.; Mahomoodally, M.F. The Versatility of Antioxidant Assays in Food Science and Safety—Chemistry, Applications, Strengths, and Limitations. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A comprehensive review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón-Martínez, V.; Delgado-Ospina, J.; Ramírez-Navas, J.S.; Flórez-López, E.; Valdés-Restrepo, M.P.; Grande-Tovar, C.D.; Chaves-López, C. Effect of Pretreatment with Low-Frequency Ultrasound on Quality Parameters in Gulupa (Passiflora edulis Sims) Pulp. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, T.; Naseem, Z.; Wani, S.M.; Sultana, A.; Bashir, I.; Amin, T.; Shafi, F.; Dhekale, B.S.; Nazki, I.T.; Zargar, I.; et al. Impact of ultrasound assisted pretreatment and drying methods on quality characteristics of underutilized vegetable purslane. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 112, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, F.; Perussello, C.A.; Zhang, Z.; Kerry, J.P.; Tiwari, B.K. Impact of ultrasound and blanching on functional properties of hot-air dried and freeze dried onions. LWT 2018, 87, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queneau, Y.; Jarosz, S.; Lewandowski, B.; Fitremann, J. Sucrose Chemistry and Applications of Sucrochemicals. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 2007, 61, 217–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Donadone, D.B.; Giombelli, C.; Silva, D.L.G.; Stevanato, N.; Silva, C.; Bolanho Barros, B.C. Ultrasound—Assisted extraction of phenolic compounds and soluble sugars from the stem portion of peach palm. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Tang, J. Ultrasonically assisted extraction of total carbohydrates from Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni and identification of extracts. Food Bioprod. Process. 2010, 88, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya; Gogate, P.R. Ultrasound-Assisted Intensification of Activity of Free and Immobilized Enzymes: A Review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 9650–9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matys, A.; Nowacka, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Wiktor, A. Chemical and Thermal Characteristics of PEF-Pretreated Strawberries Dried by Various Methods. Molecules 2024, 29, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.-B.; Qin, Y.-L.; Qi, Z.-Q.; Niu, Y.; Liu, Z.-J.; Liu, W.-X.; He, H.; Cao, Z.-M.; Yang, Y. Genome-Wide Analysis, Expression Profile, and Characterization of the Acid Invertase Gene Family in Pepper. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, L.H.M.; Pião, A.C.S.; Domingos, R.N.; Carmona, E.C. Ultrasound effects on invertase from Aspergillus niger. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 20, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Soares, A.S.; Augusto, P.E.D.; de Leite Júnior, B.R.C.; Nogueira, C.A.; Vieira, É.N.R.; de Barros, F.A.R.; Stringheta, P.C.; Ramos, A.M. Ultrasound assisted enzymatic hydrolysis of sucrose catalyzed by invertase: Investigation on substrate, enzyme and kinetics parameters. LWT 2019, 107, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohman, A.; Ghazali, M.A.B.; Windarsih, A.; Irnawati, I.; Riyanto, S.; Yusof, F.M.; Mustafa, S. Comprehensive Review on Application of FTIR Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics for Authentication Analysis of Fats and Oils in the Food Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gutiérrez, N.; Mellado-Carretero, J.; Bengoa, C.; Salvador, A.; Sanz, T.; Wang, J.; Ferrando, M.; Güell, C.; de Lamo-Castellví, S. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Combined with Multivariate Analysis Successfully Discriminates Raw Doughs and Baked 3D-Printed Snacks Enriched with Edible Insect Powder. Foods 2021, 10, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüttler, A.; Friedel, M.; Jung, R.; Rauhut, D.; Darriet, P. Characterizing aromatic typicality of Riesling wines: Merging volatile compositional and sensory aspects. Food Res. Int. 2015, 69, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarosa, N.; Ragni, L.; Laghi, L.; Tylewicz, U.; Rocculi, P.; Dalla Rosa, M. Time domain nuclear magnetic resonance to monitor mass transfer mechanisms in apple tissue promoted by osmotic dehydration combined with pulsed electric fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.-L.; Shang, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-P.; Ma, H.-J. Effect of ultrasound-assisted sodium bicarbonate treatment on gel characteristics and water migration of reduced-salt pork batters. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 89, 106150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, I.M.; Zgadzaj, A.; Kowalczyk, S.; Zalewska, A.; Oledzka, E.; Cieśla, K.; Plichta, A.; Sobczak, M. A Comprehensive Investigation of the Structural, Thermal, and Biological Properties of Fully Randomized Biomedical Polyesters Synthesized with a Nontoxic Bismuth(III) Catalyst. Molecules 2022, 27, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, M.; Segovia, C.; Baffoun, A.; Zouari, R.; Fierro, V.; Celzard, A.; Msahli, S.; Brosse, N. Influence of Anatomy, Microstructure, and Composition of Natural Fibers on the Performance of Thermal Insulation Panels. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 48673–48688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rayung, M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Shazleen, S.S.; Rani, M.S.A.; Shafi, A.R.; Aisyah, H.A.; Radzi, M.H.M.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; et al. Thermogravimetric Analysis Properties of Cellulosic Natural Fiber Polymer Composites: A Review on Influence of Chemical Treatments. Polymers 2021, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Z.; Wan, F.; Ma, G.; Xu, Y.; Wang, T.; Wu, B.; Huang, X. Enhancing peach slices radio frequency vacuum drying by combining ultrasound and ultra-high pressure as pretreatments: Effect on drying characteristics, physicochemical quality, texture and sensory evaluation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 103, 106786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, D.; Hodnett, M.; Wang, L.; Zeqiri, B. An objective comparison of commercially-available cavitation meters. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, D.; Musielak, G. Microwave and Ultrasound Assisted Rotary Drying of Carrot: Analysis of Process Kinetics and Energy Intensity. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Khan, M.K. Applications of ultrasound in food technology: Processing, preservation and extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011, 18, 813–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.L.; Kubo, M.T.K.; Caetano-Silva, M.E.; Augusto, P.E.D. Ultrasound processing of fruits and vegetables, structural modification and impact on nutrient and bioactive compounds: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 4376–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalabadi, M.; Saremnezhad, S.; Bahrami, A.; Jafari, S.M. The influence of bath and probe sonication on the physicochemical and microstructural properties of wheat starch. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 2427–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miano, A.C.; Rojas, M.L.; Augusto, P.E.D. Structural changes caused by ultrasound pretreatment: Direct and indirect demonstration in potato cylinders. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 52, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kentish, S.; Feng, H. Applications of Power Ultrasound in Food Processing. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 5, 263–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llavata, B.; Quiles, A.; Rosselló, C.; Cárcel, J.A. Enhancing ultrasonic-assisted drying of low-porosity products through pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment: The case of butternut squash. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 112, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Flaviis, R.; Sacchetti, G. A 50—Year Theoretical Gap on Color Difference in Food Science: Critical Insights and New Perspectives. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, M.; Dhenge, R.; Rodolfi, M.; Bertani, G.; Bernini, V.; Dall’Acqua, S.; Ganino, T. Understanding the Impact of High-Pressure Treatment on Physico-Chemical, Microstructural, and Microbiological Aspects of Pumpkin Cubes. Foods 2023, 12, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tappi, S.; Velickova, E.; Mannozzi, C.; Tylewicz, U.; Laghi, L.; Rocculi, P. Multi-Analytical Approach to Study Fresh-Cut Apples Vacuum Impregnated with Different Solutions. Foods 2022, 11, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, A.; Chadzynska, M.; Rybak, K.; Dadan, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D.; Nowacka, M. The Influence of Polyols on the Process Kinetics and Bioactive Substance Content in Osmotic Dehydrated Organic Strawberries. Molecules 2022, 27, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Chen, G.; Tilley, M.; Li, Y. Changes in phenolic profiles and antioxidant activities during the whole wheat bread-making process. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 12136:2000; Fruit and Vegetable Juices—Determination of Total Carotenoid Content and Individual Carotenoid Fractions. PKN: Warsaw, Poland, 2000.

- Spínola, V.; Mendes, B.; Câmara, J.S.; Castilho, P.C. An improved and fast UHPLC-PDA methodology for determination of L-ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acids in fruits and vegetables. Evaluation of degradation rate during storage. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2012, 403, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, T.; Lu, B.; Liu, R. Guidelines for antioxidant assays for food components. Food Front. 2020, 1, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, R.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z. Evaluation of Physiological Characteristics, Soluble Sugars, Organic Acids and Volatile Compounds in ‘Orin’ Apples (Malus domestica) at Different Ripening Stages. Molecules 2021, 26, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madurapperumage, A.; Johnson, N.; Thavarajah, P.; Tang, L.; Thavarajah, D. Fourier—Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) as a high—Throughput phenotyping tool for quantifying protein quality in pulse crops. Plant Phenome J. 2022, 5, e20047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, R.; Onopiuk, A.; Żbik, K.; Pobiega, K.; Piasecka, I.; Nowacka, M. Chemical and Microbiological Characterization of Freeze-Dried Superworm (Zophobas morio F.) Larvae Pretreated by Blanching and Ultrasound Treatment. Molecules 2024, 29, 5447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Ultrasound | Sample Code | Time of Treatment [min] | Medium Temperature [°C] | Conductivity [µS/cm] | CDI [-] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | F | 0 | 23.2 ± 0.28 ab | 30.9 ± 1.4 a | - * |

| Direct ultrasound | d_0.5 | 0.5 | 18.7 ± 0.28 a | 33.4 ± 2.5 ab | 0.0020 a |

| d_1 | 1 | 19.0 ± 0.07 a | 37.9 ± 4.2 bc | 0.0070 a | |

| d_2 | 2 | 18.7 ± 0.28 a | 40.6 ± 5.1 cd | 0.0099 ab | |

| d_3 | 3 | 23.2 ± 0.28 ab | 44.6 ± 1.5 de | 0.0143 bc | |

| d_5 | 5 | 23.2 ± 0.28 ab | 47.3 ± 1.7 e | 0.0173 c | |

| Indirect ultrasound | i_5 | 5 | 24.3 ± 0.07 ab | 32.4 ± 1.4 ab | 0.0015 a |

| i_10 | 10 | 24.8 ± 0.07 b | 35.5 ± 2.0 abc | 0.0050 a | |

| i_15 | 15 | 25.1 ± 0.14 c | 36.5 ± 1.3 bc | 0.0061 a | |

| i_20 | 20 | - | - * | - | |

| i_30 | 30 | 27.5 ± 0.14 d | 37.9 ± 1.9 bc | 0.0077 ab |

| Type of Ultrasound | Sample Code | Color [-] | Texture | Microbial Quality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔE Top | ΔE Bottom | Color of Top | Color of Bottom | Hardness [N] | TVC [log CFU/g] | TYM [log CFU/g] | ||

| Fresh | F | - * | - |  |  | 52.3 ± 4.5 ab | 4.57 ± 0.05 | 3.51 ± 0.02 |

| Direct ultrasound | d_0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.9 abc | 5.5 ± 0.9 a |  |  | 50.4 ± 4.1 ab | 3.25 ± 0.26 | 3.38 ± 0.04 |

| d_1 | 2.1 ± 1.0 abc | 8.4 ± 2.0 ab |  |  | 52.7 ± 2.7 ab | 3.13 ± 0.10 | 3.10 ± 0.02 | |

| d_2 | 1.8 ± 0.9 ab | 11.8 ± 1.0 cde |  |  | 52.0 ± 3.0 ab | 3.10 ± 0.07 | 2.61 ± 0.05 | |

| d_3 | 2.9 ± 1.5 abc | 8.8 ± 2.3 bc |  |  | 52.2 ± 4.6 ab | 2.35 ± 0.05 | nd # | |

| d_5 | 3.9 ± 1.1 bc | 13.0 ± 2.9 e |  |  | 48.5 ± 4.5 a | 1.53 ± 0.17 | nd | |

| Indirect ultrasound | i_5 | 8.3 ± 1.1 d | 14.6 ± 0.4 ef |  |  | 52.1 ± 4.7 ab | 2.19 ± 0.13 | 1.30 ± 0.25 |

| i_10 | 2.8 ± 1.6 abc | 11.4 ± 1.4 bcde |  |  | 53.8 ± 2.5 ab | 2.15 ± 0.11 | 1.16 ± 0.22 | |

| i_15 | 4.1 ± 1.4 c | 12.4 ± 2.3 de |  |  | 50.5 ± 4.8 ab | 2.05 ± 0.18 | nd | |

| i_20 | 1.6 ± 0.6 a | 9.5 ± 1.6 bcd |  |  | 51.5 ± 4.6 ab | 1.36 ± 0.32 | nd | |

| i_30 | 1.1 ± 0.9 a | 17.8 ± 0.8 f |  |  | 55.8 ± 3.2 b | 1.00 ± 0.01 | nd | |

| Type of Ultrasound | Tested Time Range [min] | Temperature Range During Experiments [°C] | CDI Range [-] | Reason for Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct ultrasound (probe) | 0.5–10 | 16.0–23.6 (with cooling) | 0.003–0.029 | Higher times caused strong tissue damage (high CDI), which could bias chemical results, 0.5–5 min ensured structural modification without overheating. |

| Indirect ultrasound (bath) | 5–60 | 23.2–30.1 | 0.0007–0.009 | Long times (>30 min) resulted in gradual temperature increase and structural softening; 5–30 min ensured mild treatment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rybak, K.; Skarżyńska, A.; Ossowski, S.; Dadan, M.; Pobiega, K.; Nowacka, M. Insight into the Molecular and Structural Changes in Red Pepper Induced by Direct and Indirect Ultrasonic Treatments. Molecules 2025, 30, 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244668

Rybak K, Skarżyńska A, Ossowski S, Dadan M, Pobiega K, Nowacka M. Insight into the Molecular and Structural Changes in Red Pepper Induced by Direct and Indirect Ultrasonic Treatments. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244668

Chicago/Turabian StyleRybak, Katarzyna, Aleksandra Skarżyńska, Szymon Ossowski, Magdalena Dadan, Katarzyna Pobiega, and Małgorzata Nowacka. 2025. "Insight into the Molecular and Structural Changes in Red Pepper Induced by Direct and Indirect Ultrasonic Treatments" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244668

APA StyleRybak, K., Skarżyńska, A., Ossowski, S., Dadan, M., Pobiega, K., & Nowacka, M. (2025). Insight into the Molecular and Structural Changes in Red Pepper Induced by Direct and Indirect Ultrasonic Treatments. Molecules, 30(24), 4668. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244668