Anti-Invasive and Apoptotic Effect of Eupatilin on YD-10B Human Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

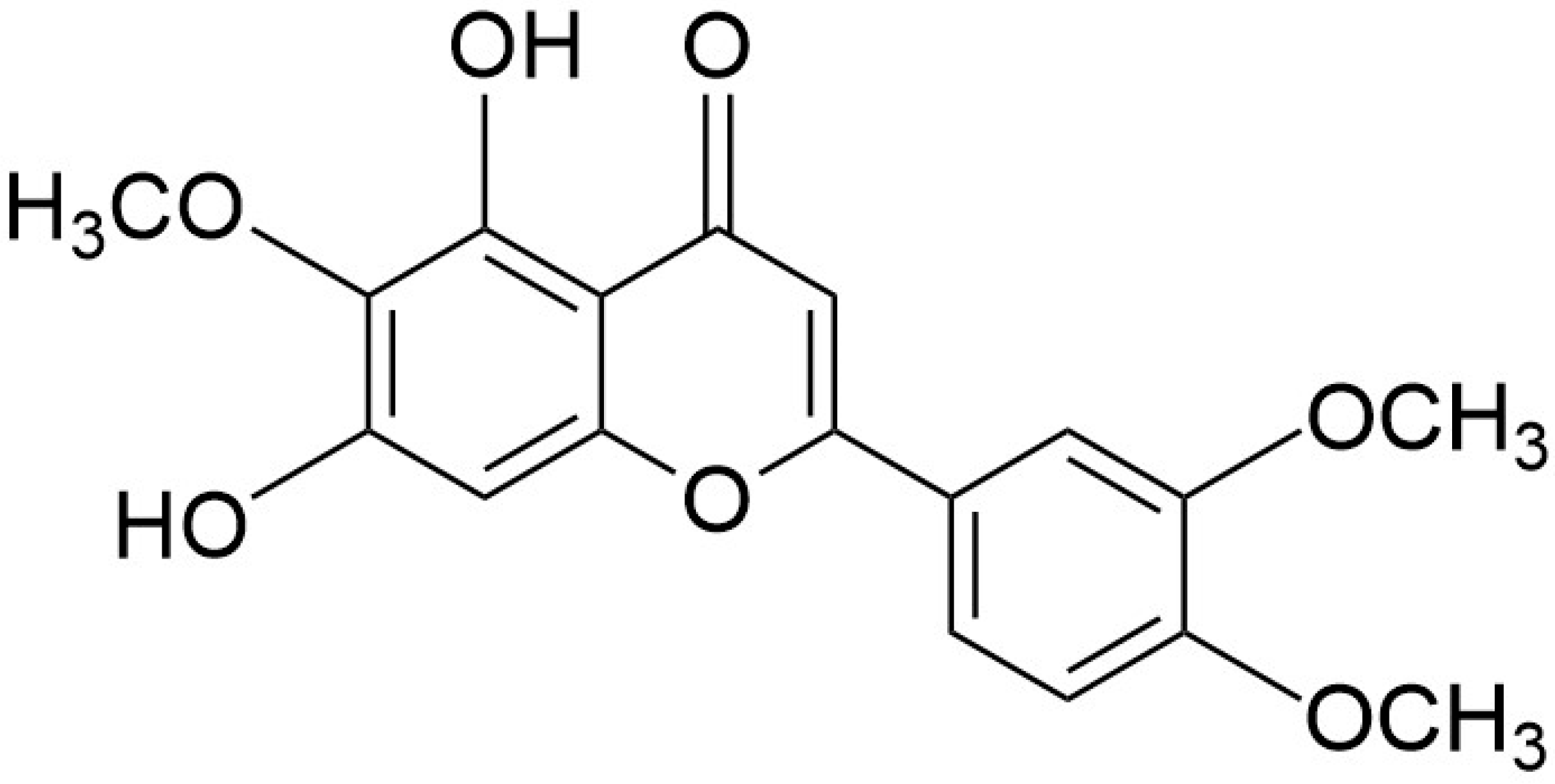

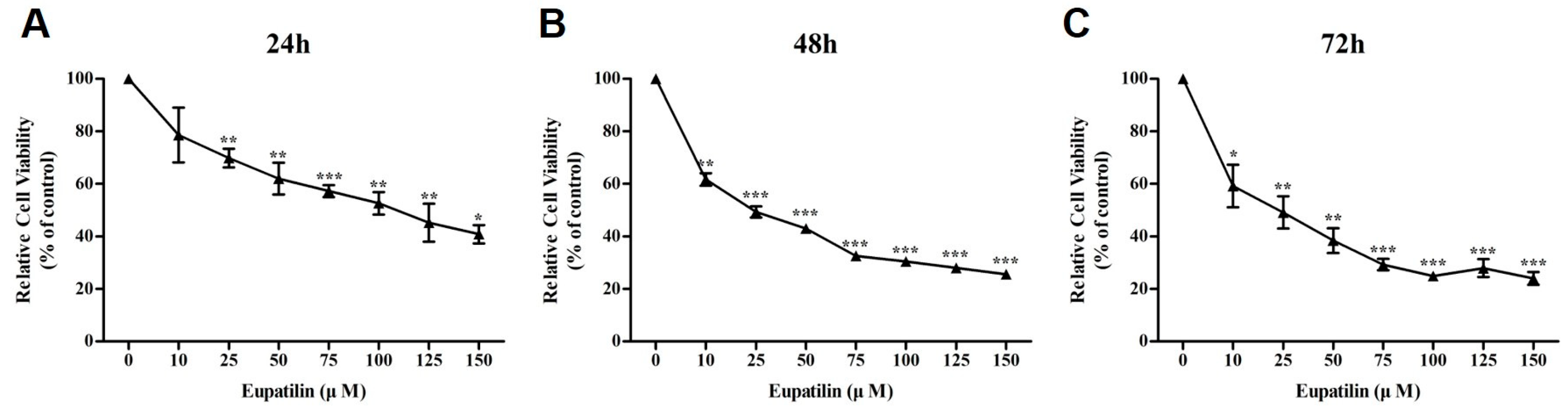

2.1. Effect of Eupatilin on the Viability of YD-10B Cells

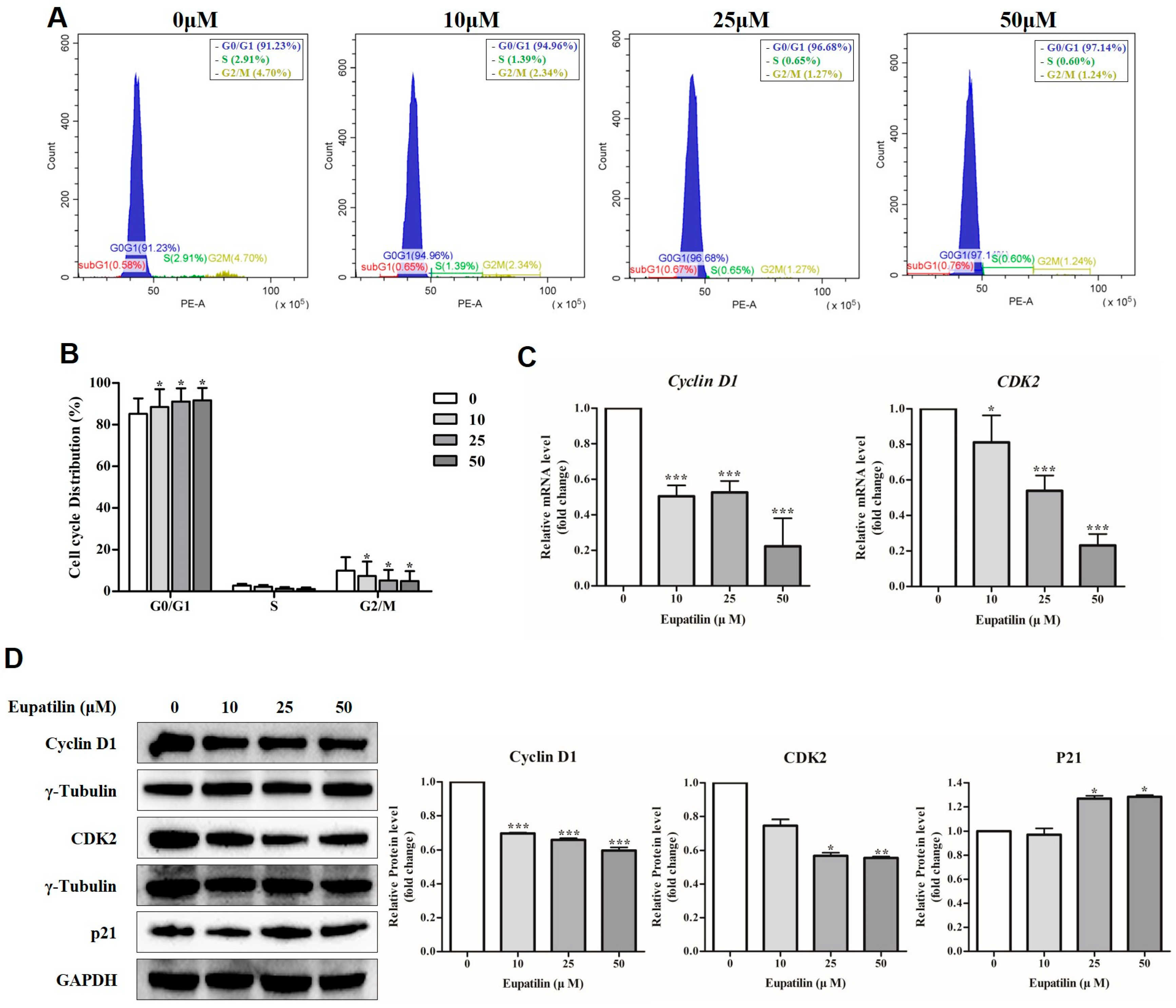

2.2. Cell Cycle Regulation by Eupatilin

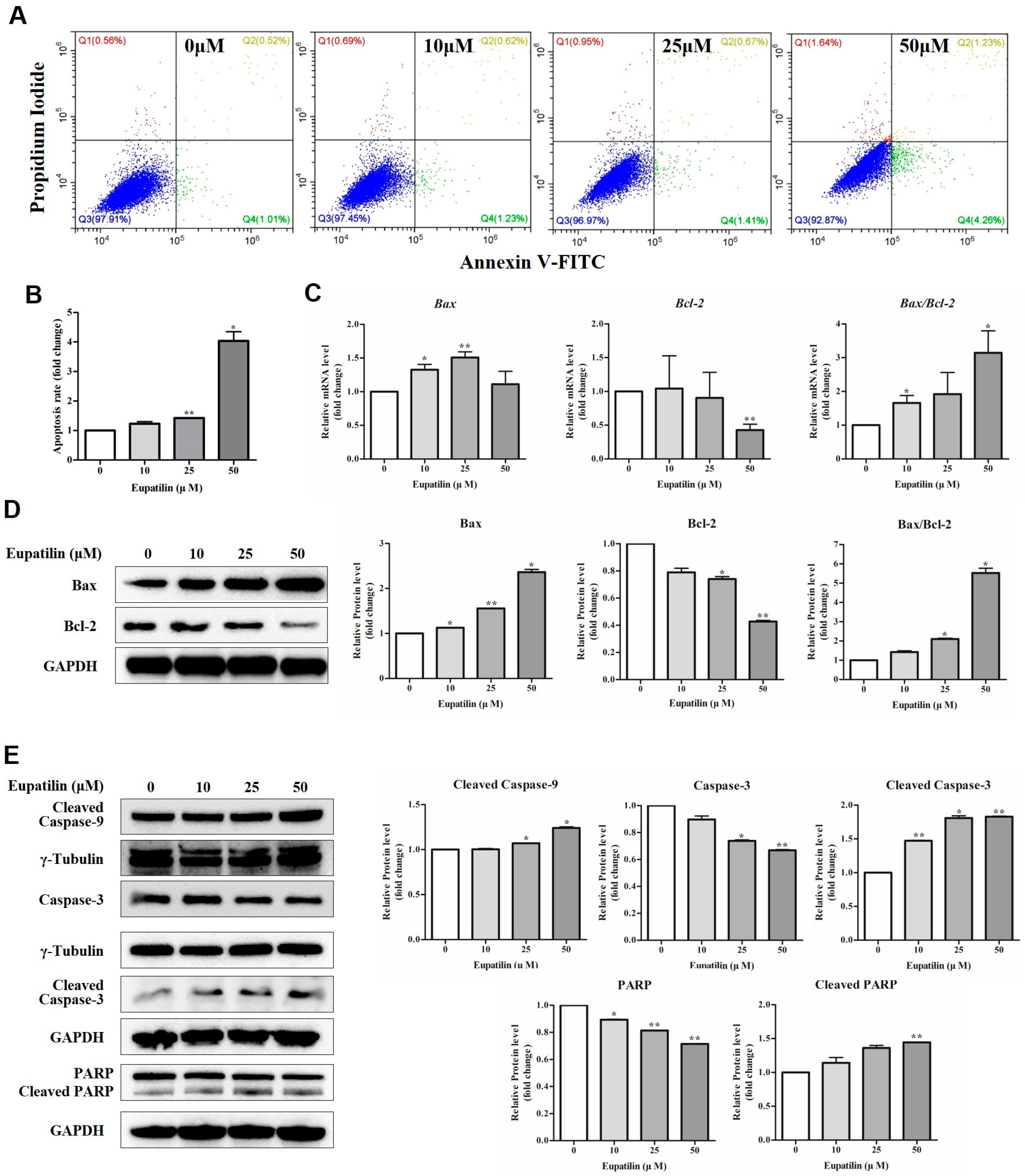

2.3. Induction of Apoptosis by Eupatilin

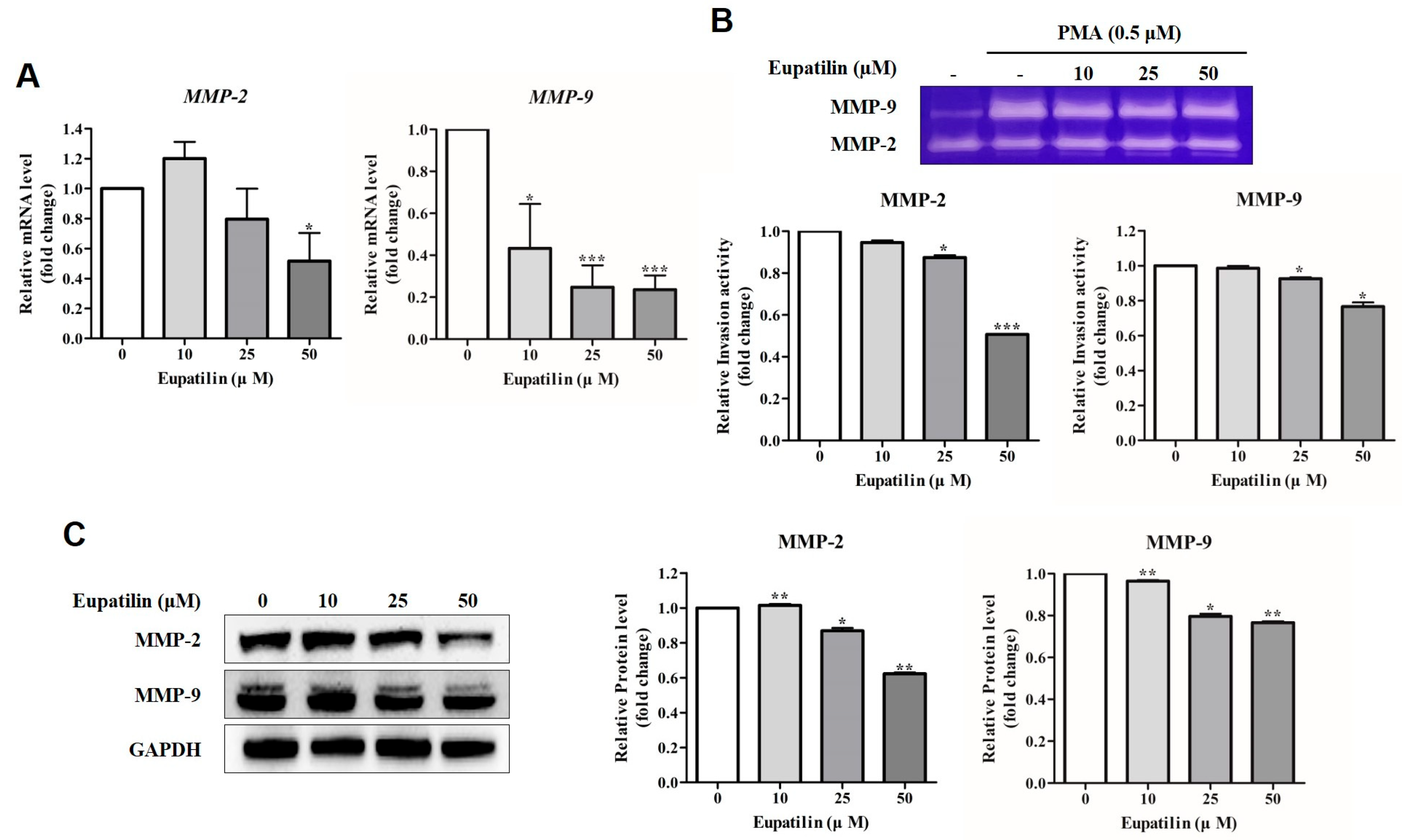

2.4. Effect of Eupatilin on Invasion of YD-10B Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Cell Culture and Eupatilin Treatment

4.3. Dimethylthiazole-2′, 5′-Diphenyl-2-H-Tetrazlium Bromide (MTS) Assay

4.4. Cell Cycle Analysis

4.5. Annexin V-FITC Analysis

4.6. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.7. Western Blot

4.8. Gelatin Zymography

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Huang, Z.; Qin, S.; Nice, E.C.; Tang, J.; Huang, C. Oral squamous cell carcinomas: State of the field and emerging directions. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, R.J.; Ironside, J.A. Squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. BMJ 2002, 325, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.A.; Estefan, D.J. Assessing oral malignancies. Am. Fam. Physician. 2002, 65, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, L.; Hong, W.K.; Papadimitrakopoulou, V.A. Focus on head and neck cancer. Cancer Cell 2004, 5, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Global Cancer Observatory; IARC; WHO. Lip, Oral Cavity Cancer. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/1-Lip-oral-cavity-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Romano, A.; Di Stasio, D.; Petruzzi, M.; Fiori, F.; Lajolo, C.; Santarelli, A.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Contaldo, M. Noninvasive Imaging Methods to Improve the Diagnosis of Oral Carcinoma and Its Precursors: State of the Art and Proposal of a Three-Step Diagnostic Process. Cancers 2021, 13, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, H. The role of cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption in the differentiation of oral squamous cell carcinoma for the males in China. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, C.F.; de Angelis, B.B.; Prudente, H.M.; de Souza, B.V.; Cardoso, S.V.; de Azambuja Ribeiro, R.I. Concomitant consumption of marijuana, alcohol and tobacco in oral squamous cell carcinoma development and progression: Recent advances and challenges. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissowska, J.; Pilarska, A.; Pilarski, P.; Samolczyk-Wanyura, D.; Piekarczyk, J.; Bardin-Mikolłajczak, A.; Zatonski, W.; Herrero, R.; Muňoz, N.; Franceschi, S. Smoking, alcohol, diet, dentition and sexual practices in the epidemiology of oral cancer in Poland. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2003, 12, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Nelson, H.H.; Peters, E.; Ringstrom, E.; Posner, M.; Kelsey, K.T. Patterns of gene promoter methylation in squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. Oncogene 2002, 21, 4231–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, A.M.; Lee, C.H.; Ko, Y.C. Betel quid-associated cancer: Prevention strategies and targeted treatment. Cancer Lett. 2020, 477, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chua, N.Q.E.; Dang, S.; Davis, A.; Chong, K.W.; Prime, S.S.; Cirillo, N. Molecular Mechanisms of Malignant Transformation of Oral Submucous Fibrosis by Different Betel Quid Constituents-Does Fibroblast Senescence Play a Role? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.; Liu, J.; Masterson, L.; Fenton, T.R. HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer: Epidemiology, molecular biology and clinical management. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Dong, Y. Human papillomavirus and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A review of HPV-positive oral squamous cell carcinoma and possible strategies for future. Curr. Probl. Cancer 2017, 41, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrup, P. Can we prevent malignancy by treating premalignant lesions? Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 549–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morandi, L.; Gissi, D.; Tarsitano, A.; Asioli, S.; Gabusi, A.; Marchetti, C.; Montebugnoli, L.; Foschini, M.P. CpG location and methylation level are crucial factors for the early detection of oral squamous cell carcinoma in brushing samples using bisulfite sequencing of a 13-gene panel. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujan, O.; Glenny, A.M.; Oliver, R.J.; Thakker, N.; Sloan, P. Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 11, CD004150. [Google Scholar]

- Linsen, S.S.; Gellrich, N.C.; Krüskemper, G. Age- and localization-dependent functional and psychosocial impairments and health related quality of life six months after OSCC therapy. Oral Oncol. 2018, 81, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.K.; Schuderer, J.G.; Zeman, F.; Klingelhöffer, C.; Hullmann, M.; Spanier, G.; Reichert, T.E.; Ettl, T. Health-related quality of life: A retrospective study on local vs. microvascular reconstruction in patients with oral cancer. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, K.A.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, E.S. Targeted therapies in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer 2009, 115, 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.P.; Gil, Z. Current concepts in management of oral cancer--surgery. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.; Macluskey, M.; Mc Goldrick, N.; Conway, D.I.; Glenny, A.-M.; Clarkson, J.E.; Worthington, H.V.; Chan, K.K. Interventions for the treatment of oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer: Chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 12, CD006386. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Q.-L.; Li, X.-L.; Tian, T.; Li, S.; Shi, R.-Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, J.-G. Application of Natural Medicinal Plants Active Ingredients in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 30, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitea, G.; Schröder, V.; Iancu, I.M.; Mireșan, H.; Iancu, V.; Bucur, L.A.; Badea, F.C. Molecular Targets of Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2024, 16, 3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, L.; Fan, D.; Yi, X.; Cao, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, L. Curcumin inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma proliferation and invasion via EGFR signaling pathways. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 6438–6446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, M.J.; Lin, C.C.; Lo, Y.S.; Chuang, Y.C.; Ho, H.Y.; Chen, M.K. Chrysosplenol D Triggers Apoptosis through Heme Oxygenase-1 and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T. Methoxylated flavones: Bioavailability and mode of action. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2007, 17, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Lyu, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, N.; Tan, S.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X. Eupatilin inhibits pulmonary fibrosis by activating Sestrin2/PI3K/Akt/mTOR dependent autophagy pathway. Life Sci. 2023, 334, 122218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.C.; Oh, J.-M.; Choi, H.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, B.G.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.-S. Eupatilin Inhibits Reactive Oxygen Species Generation via Akt/NF-κB/MAPK Signaling Pathways in Particulate Matter-Exposed Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Toxics 2021, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Wu, L.; Yang, H.; Liu, T.; Tong, Y.; Wan, J.; Han, B.; Zhou, L.; Hu, X. Eupatilin inhibits xanthine oxidase in vitro and attenuates hyperuricemia and renal injury in vivo. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 183, 114307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-J.; Hong, S.-H.; Yoon, M.-J.; Lee, K.-A.; Choi, D.H.; Kwon, H.; Ko, J.-J.; Koo, H.S.; Kang, Y.-J. Eupatilin treatment inhibits transforming growth factor beta-induced endometrial fibrosis in vitro. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2020, 47, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouillamoz, J.F.; Carlen, C.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Pollastro, F.; Appendino, G. The génépi Artemisia species. Ethnopharmacology, cultivation, phytochemistry, and bioactivity. Fitoterapia 2015, 106, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.J.; Lee, S.; Chae, J.R.; Lee, H.S.; Jun, C.D.; Kim, S.H. Eupatilin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. Life Sci. 2011, 88, 1121–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.H. Eupatilin inhibits H2O2-induced apoptotic cell death through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-kappaB. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 2865–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Chen, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, F.; Jiang, Y.; Lu, J.; et al. Eupatilin inhibits the proliferation of human esophageal cancer TE1 cells by targeting the Akt-GSK3β and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades. Oncol. Rep. 2018, 39, 2942–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Piras, F.; Pollastro, F.; Sogos, V.; Appendino, G.; Nieddu, M. Comparative Evaluation of Anticancer Activity of Natural Methoxylated Flavones Xanthomicrol and Eupatilin in A375 Skin Melanoma Cells. Life 2024, 14, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, N.; Zhong, K.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wan, P.; Lu, S.; Yang, L.; Liu, S. Eupatilin Inhibits Renal Cancer Growth by Downregulating MicroRNA-21 through the Activation of YAP1. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 5016483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Ding, B.; Fu, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Xu, R. Eupatilin inhibits glioma proliferation, migration, and invasion by arresting cell cycle at G1/S phase and disrupting the cytoskeletal structure. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 4781–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.-F.; Wang, X.-H.; Pan, B.; Li, F.; Kuang, L.; Su, Z.-X. Eupatilin induces human renal cancer cell apoptosis via ROS-mediated MAPK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Oncol Lett. 2016, 12, 2894–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytil, A.; Waltner-Law, M.; West, R.; Friedman, D.; Aakre, M.; Barker, D.; Law, B. Construction of a cyclin D1-Cdk2 fusion protein to model the biological functions of cyclin D1-Cdk2 complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 47688–47698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, K.J.; Sarcevic, B.; Sutherland, R.L.; Musgrove, E.A. Cyclin D2 activates Cdk2 in preference to Cdk4 in human breast epithelial cells. Oncogene 1997, 14, 1329–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, L.R.; Daigh, L.H.; Chung, M.; Meyer, T. Clinical CDK4/6 inhibitors induce selective and immediate dissociation of p21 from cyclin D-CDK4 to inhibit CDK2. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.; Wu, H.; Dong, Y.G.; Lin, B.O.; Xu, G.; Ma, Y.B. Application of eupatilin in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 2505–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, H.J.; Surh, Y.J. Eupatilin, a pharmacologically active flavone derived from Artemisia plants, induces apoptosis in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Mutat. Res. 2001, 496, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.L.; Cornelius, L.A. Matrix metalloproteinases: Pro- and anti-angiogenic activities. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2000, 5, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassiouni, W.; Ali, M.A.M.; Schulz, R. Multifunctional intracellular matrix metalloproteinases: Implications in disease. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 7162–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Kang, Q.; Chan, K.I.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Z.; Tan, W. The immunomodulatory role of matrix metalloproteinases in colitis-associated cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1093990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, R.; Fuerst, T.; Bird, R.; Hoyhtya, M.; Oelkuct, M.; Kraus, S.; Komarek, D.; Liotta, L.; Berman, M.; Stetler-Stevenson, W. Domain structure of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. Characterization of proteolytic activity and identification of the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) binding regions. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 15398–15405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.; Prekeris, R. The regulation of MMP targeting to invadopodia during cancer metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, J.-C.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Kang, K.S.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, S.-N. Eupatilin with PPARα agonistic effects inhibits TNFα-induced MMP signaling in HaCaT cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 493, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.; Singh, B.; Schuster, G. Induction of apoptosis in oral cancer cells: Agents and mechanisms for potential therapy and prevention. Oral Oncol. 2004, 40, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, B.A.; El-Deiry, W.S. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, M.; Quispe, C.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Pons-Fuster, E.; Lopez-Jornet, P.; Zam, W.; Das, T.; Dey, A.; Kumar, M.; Pentea, M.; et al. Naturally-Occurring Bioactives in Oral Cancer: Preclinical and Clinical Studies, Bottlenecks and Future Directions. Front. Biosci. 2022, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathi, N.; Rajan, S.T.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Natural products and diet for the prevention of oral cancer: Research from south and southeast Asia. Oral Dis. 2025, 31, 1503–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaoka, T.; Ota, A.; Ono, T.; Karnan, S.; Konishi, H.; Furuhashi, A.; Ohmura, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Hosokawa, Y.; Kazaoka, Y. Combined arsenic trioxide-cisplatin treatment enhances apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cell Oncol. 2014, 37, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Guo, S.; Xiong, X.-K.; Peng, B.-Y.; Huang, J.-M.; Chen, M.-F.; Wang, F.-Y.; Wang, J.-N. Combination of quercetin and cisplatin enhances apoptosis in OSCC cells by downregulating xIAP through the NF-κB pathway. J. Cancer. 2019, 10, 4509–4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, G.; Park, H.-J.; Jung, S.-Y.; Kim, E.-J. Anti-Invasive and Apoptotic Effect of Eupatilin on YD-10B Human Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells. Molecules 2025, 30, 4666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244666

Kim G, Park H-J, Jung S-Y, Kim E-J. Anti-Invasive and Apoptotic Effect of Eupatilin on YD-10B Human Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells. Molecules. 2025; 30(24):4666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244666

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Gaeun, Hyun-Jung Park, Suk-Yul Jung, and Eun-Jung Kim. 2025. "Anti-Invasive and Apoptotic Effect of Eupatilin on YD-10B Human Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells" Molecules 30, no. 24: 4666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244666

APA StyleKim, G., Park, H.-J., Jung, S.-Y., & Kim, E.-J. (2025). Anti-Invasive and Apoptotic Effect of Eupatilin on YD-10B Human Oral Squamous Carcinoma Cells. Molecules, 30(24), 4666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30244666