A Core–Shell Pt–NiSe@NiFe-LDH Heterostructure for Bifunctional Alkaline Water Splitting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental Sections

3.1. Synthesis of NiSe Catalyst

3.2. Synthesis of NiSe@NiFe-LDH Catalyst

3.3. Synthesis of Pt-NiSe@NiFe-LDH Catalyst

3.4. Synthesis of Pt-NiSe@NiFe-LDH-Ov Catalyst

4. Electrocatalytic Performance Evaluation

5. Material Characterization

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andaveh, R.; Sabour Rouhaghdam, A.; Ai, J.; Maleki, M.; Wang, K.; Seif, A.; Barati Darband, G.; Li, J. Boosting the electrocatalytic activity of NiSe by introducing MnCo as an efficient heterostructured electrocatalyst for large-current-density alkaline seawater splitting. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2023, 325, 122355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z.; Tao, J.; Gu, R.; Liu, Y. Fe-Doped NiSe Porous Nanosheets as Bifunctional Electrocatalysts for Efficient Overall Water Splitting. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 13296–13304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghafar, F.; Xu, X.; Jiang, S.P.; Shao, Z. Perovskite for Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution at Elevated Temperatures. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, K.R.; Tran, D.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, J.H. Copper-Incorporated heterostructures of amorphous NiSex/Crystalline NiSe2 as an efficient electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 422, 130048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, D.; Chai, D.-F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, G. Electrocatalysis through interface and structural engineering of hollow/porous NiSe/CoSe2 nanotubes for overall water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 976, 173092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, A.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y. Bifunctional heterostructured nitrogen-doped carbon-layer-loaded NiSe2-FeSe2 electrocatalyst for efficient water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 89, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Li, X.; Xu, S.-L.; Zhao, R.-D.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, D.-P.; Li, M.; et al. Multidimensional Engineering Strategies for Transition Metal Selenide Electrocatalysts in Water Electrolysis with Performance Optimization Mechanisms and Future Perspectives. Chem. Rec. 2025, 25, e202500082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, P.; Gao, L. Mesoporous Co-MoS2 with sulfur vacancies: A bifunctional electrocatalyst for enhanced water-splitting reactions in alkaline media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-Y.; Xu, S.-L.; Li, J.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, R.-D.; Wu, F.-F.; Zhao, D. Excellent electrocatalytic performance of CuCo2S4 nanowires for high-efficiency overall water splitting in alkaline and seawater media. CrystEngComm 2025, 27, 3700–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, Z.; Fu, H.; Zhang, X.; Tian, G.; Fu, H. NiSe-Ni0.85Se Heterostructure Nanoflake Arrays on Carbon Paper as Efficient Electrocatalysts for Overall Water Splitting. Small 2018, 14, 1800763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Wang, W.; Liao, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, C. Hierarchical FeCo LDH/NiSe heterostructure electrocatalysts with rich heterointerfaces for robust water splitting at an industrial-level current density. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shang, H.; Xu, H.; Du, Y. Nanoboxes endow non-noble-metal-based electrocatalysts with high efficiency for overall water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 857–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, X.; Tang, T.; Zhong, Y.; Shao, Z. Perovskite-Based Electrocatalysts for Cost-Effective Ultrahigh-Current-Density Water Splitting in Anion Exchange Membrane Electrolyzer Cell. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2201099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Meng, X. Recent advances in transition metal selenides-based electrocatalysts: Rational design and applications in water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 918, 165719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Cao, J.; Qi, J. Modification strategies on transition metal-based electrocatalysts for efficient water splitting. J. Energy Chem. 2021, 58, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Padmajan Sasikala, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, T.-D.; Lee, G.S.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, S.O.; Prabhakaran, P. Dimension-engineered gold heterostructures with transition metal dichalcogenide for efficient overall water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 686, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.-S.; Li, R.-Y.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.-Q.; Zhao, R.-D.; Xiang, J.; Wu, F.-F.; Zhao, D.-P. Hydrothermally synthesized NiSe2 nanospheres for efficient bifunctional electrocatalysis in alkaline seawater electrolysis: High performance and stability in HER and OER. Mater. Res. Bull. 2025, 189, 113463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudoi, R.; Saikia, L. Heteroatom Doping, Defect Engineering, and Stability of Transition Metal Diselenides for Electrocatalytic Water Splitting. Chem. Asian J. 2025, 20, e00755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.K.; Pradhan, D. NiSe2-Nanooctahedron as an Efficient Electrocatalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 2088–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zheng, J.; Tao, S.; Qian, B. Electrochemical and electrocatalytic performance of FeSe2 nanoparticles improved by selenium matrix. Mater. Lett. 2021, 284, 128947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Xu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, S.; Kong, F.; An, C. N-doped CoSe2 nanomeshes as highly-efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 893, 162328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; He, Q.; Qu, Y.; Dong, J.; Shoko, E.; Yan, P.; Taylor Isimjan, T.; Yang, X. Designing coral-like Fe2O3-regulated Se-rich CoSe2 heterostructure as a highly active and stable oxygen evolution electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 904, 115928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Tang, S.; Wu, X.; Bando, Y. NiSe@La-FeNi3 Electrocatalysts Enable Efficient Water Splitting. Energy Fuels 2025, 39, 12165–12172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Lin, X. Lignin-assisted electronic modulation on NiSe/FeOx heterointerface for boosting electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-Y.; Xu, S.-L.; Li, J.; Zhao, X.-X.; Zhao, R.-D.; Zhang, M.-C.; Zhao, D.-P.; Miao, L. Ruthenium-modified oxygen-deficient NiCoP catalysts for efficient electrocatalytic water splitting. CrystEngComm 2025, 27, 5485–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Min, B.; Li, H.; Liu, F.; Zheng, M.; Ding, K.; Lu, S.; Liu, M. NiFe-LDH coated NiSe/Ni foam as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. React. Chem. Eng. 2023, 8, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Shi, R.; Chen, C.; Wu, D.; Zhou, C.; Wang, P. Ultrafine and low-loading Pt nanoparticles anchored in NiFe-LDH as overall water splitting electrocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 166, 150892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Xue, M.; Bao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, P.; Xu, X.; Duo, S. Fabrication of Ni/NiFe-LDH Core–Shell Schottky Heterojunction as Ultrastable Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Ampere-Level Current Density Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 4683–4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappan, S.; Gurusamy, H.; Minhas, H.; Karmakar, A.; Ravichandran, S.; Pathak, B.; Kundu, S. Unraveling the Synergistic Role of Sm3+ Doped NiFe-LDH as High-Performance Electrocatalysts for Improved Anion Exchange Membrane and Water Splitting Applications. Small Methods 2025, 9, 2401655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Meng, X.; Lu, L.; Wang, Z.L.; Sun, C. Triboelectric nanogenerators powered electrodepositing tri-functional electrocatalysts for water splitting and rechargeable zinc-air battery: A case of Pt nanoclusters on NiFe-LDH nanosheets. Nano Energy 2020, 72, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, R.; Xu, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, X.; Wu, F.; Zhao, D. Interface Engineering Induced Homogeneous Isomeric Bimetallic of CoSe/NiSe2 Electrocatalysts for High Performance Water/Seawater Splitting. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2400849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jang, H.; Kim, M.G.; Qin, Q.; Liu, X.; Cho, J. Fe, Al-co-doped NiSe2 nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide as an efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 13680–13687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Chu, C.; Wei, L.; Li, H.; Shen, J. Self-supporting trace Pt-decorated ternary metal phosphide as efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst for water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1009, 176946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, F.; Fan, G.; Cheng, F. Electrodeposition of Pt-Decorated Ni(OH)2/CeO2 Hybrid as Superior Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Water Splitting. Research 2020, 2020, 9068270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Bao, W.; Zhang, J.; Ai, T.; Wu, D.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Feng, L. Ultrathin MoS2 nanosheets decorated on NiSe nanowire arrays as advanced trifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting and urea electrolysis. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 121, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, K.; Tian, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, F.; Lv, Q.; Yao, W.; Xiao, F.; et al. Oxygen vacancies engineered CoMoO4 nanosheet arrays as efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. J. Catal. 2020, 381, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmalingam, S.T.; Sharma, P.; Sunda, A.P.; Minakshi, M.; Sivasubramanian, R. Nano Hexagon NiCeO2 for Al–Air Batteries: A Combined Experimental and Density Functional Theory Study of Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activity. ChemElectroChem 2025, 12, e202500274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Ren, Y.; Mu, N.; Zuo, S.; Zou, C.; Zhou, W.; Wen, L.; Tao, H.; Zhou, W.; Lai, Z.; et al. Dynamic Redox Induced Localized Charge Accumulation Accelerating Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2405447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subashini, C.; Sivasubramanian, R.; Sundaram, M.M.; Priyadharsini, N. The evolution of allotropic forms of Na2CoP2O7 electrode and its role in future hybrid energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 130, 117390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Marley-Hines, M.; Chakravarty, S.; Nath, M. Multi-walled carbon nanotube supported manganese selenide as a highly active bifunctional OER and ORR electrocatalyst. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 6772–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-X.; Wu, L.-K.; Hou, G.-Y.; Tang, Y.-P.; Cao, H.-Z.; Zheng, G.-Q. Hierarchical NiSe@Ni nanocone arrays electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochim. Acta 2020, 353, 136519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shou, Q.; Yang, S.; Mei, H.; Yin, R.; Lu, J.; Kong, L.; Wei, W. A heterostructure NiSe2 nanoparticle @ FeSe2 microrod catalyst for efficient electrocatalytic oxygen evolution. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2025, 55, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.H.K.; Pandit, M.A.; Muralidharan, K. NiSe Nanoparticles Embedded Bimetallic MoCo Nanoflakes as an Effective Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Water Splitting. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 17878–17890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, S.K.; Ganesan, V.; Kim, J. NiSe2–FeSe Double-Shelled Hollow Polyhedrons as Superior Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 12998–13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Chang, B.; Shao, Y.; Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Hao, X. Regulating Phase Conversion from Ni3Se2 into NiSe in a Bifunctional Electrocatalyst for Overall Water-Splitting Enhancement. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Fu, L.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Tang, J. Hydrothermal Synthesis of Co-MoS2 as a Bifunctional Catalyst for Overall Water Splitting. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 15129–15142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalysts | Overpotential | Tafel (mV dec−1) | Electrolyte | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnSe@MWCNT | OER: 290 mV@10 | 54.76 | 1 M KOH | [40] |

| O-NiSe180-12@Ni/SS | OER: 290 mV@10 | 48 | 1 M KOH | [41] |

| FeSe2/NiSe2 | OER: 316 mV@20 | 137 | 1 M KOH | [42] |

| MoCo–NiSe (8:1) | OER: 277 mV@10 | 139 | 1 M KOH | [43] |

| NiSe2-FeSe DHP | OER: 280 mV@10 | 58 | 1 M KOH | [44] |

| NiSe/NF-4 | OER: 370 mV@100 | 95.3 | 1 M KOH | [45] |

| Co–MoS2 | OER: 312 mV@10 | — | 1 M KOH | [46] |

| HER: 297 mV@10 | ||||

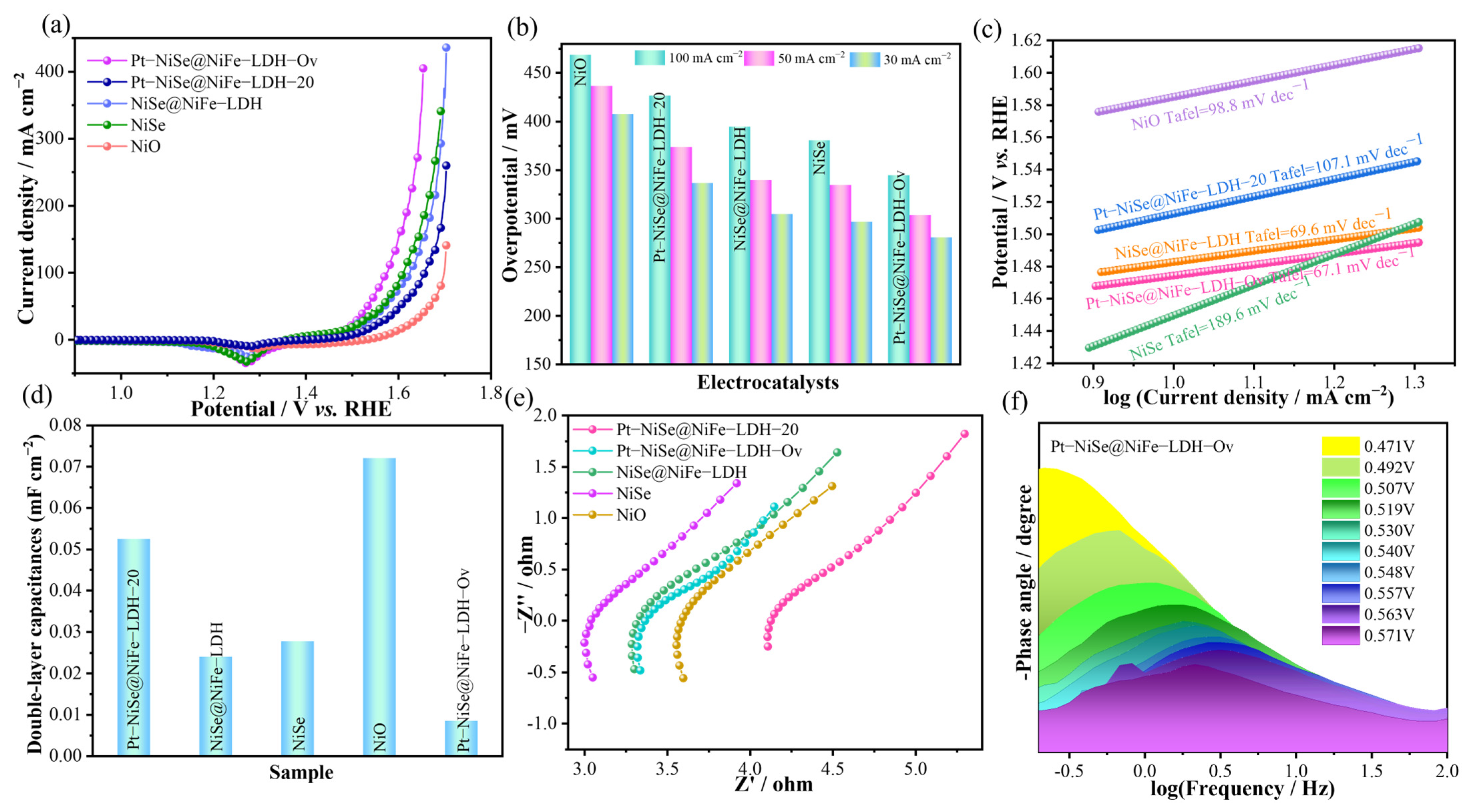

| Pt-NiSe@NiFe-LDH-Ov | OER: 344 mV@100 | 67.1 | 1 M KOH | our work |

| OER: 280 mV@30 | ||||

| HER: 280 mV@10 | 153.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, D.; Guo, R.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Z. A Core–Shell Pt–NiSe@NiFe-LDH Heterostructure for Bifunctional Alkaline Water Splitting. Molecules 2025, 30, 4654. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234654

Li S, Guo Y, Wang Z, Zhao D, Guo R, Gao Q, Zhang Z. A Core–Shell Pt–NiSe@NiFe-LDH Heterostructure for Bifunctional Alkaline Water Splitting. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4654. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234654

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Shanshan, Yanping Guo, Ziqi Wang, Depeng Zhao, Rui Guo, Qingzhong Gao, and Zhiqiang Zhang. 2025. "A Core–Shell Pt–NiSe@NiFe-LDH Heterostructure for Bifunctional Alkaline Water Splitting" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4654. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234654

APA StyleLi, S., Guo, Y., Wang, Z., Zhao, D., Guo, R., Gao, Q., & Zhang, Z. (2025). A Core–Shell Pt–NiSe@NiFe-LDH Heterostructure for Bifunctional Alkaline Water Splitting. Molecules, 30(23), 4654. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234654