Aldose Reductase Inhibition by Orthosiphon stamineus Extracts and Constituents Suggests Antioxidant Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

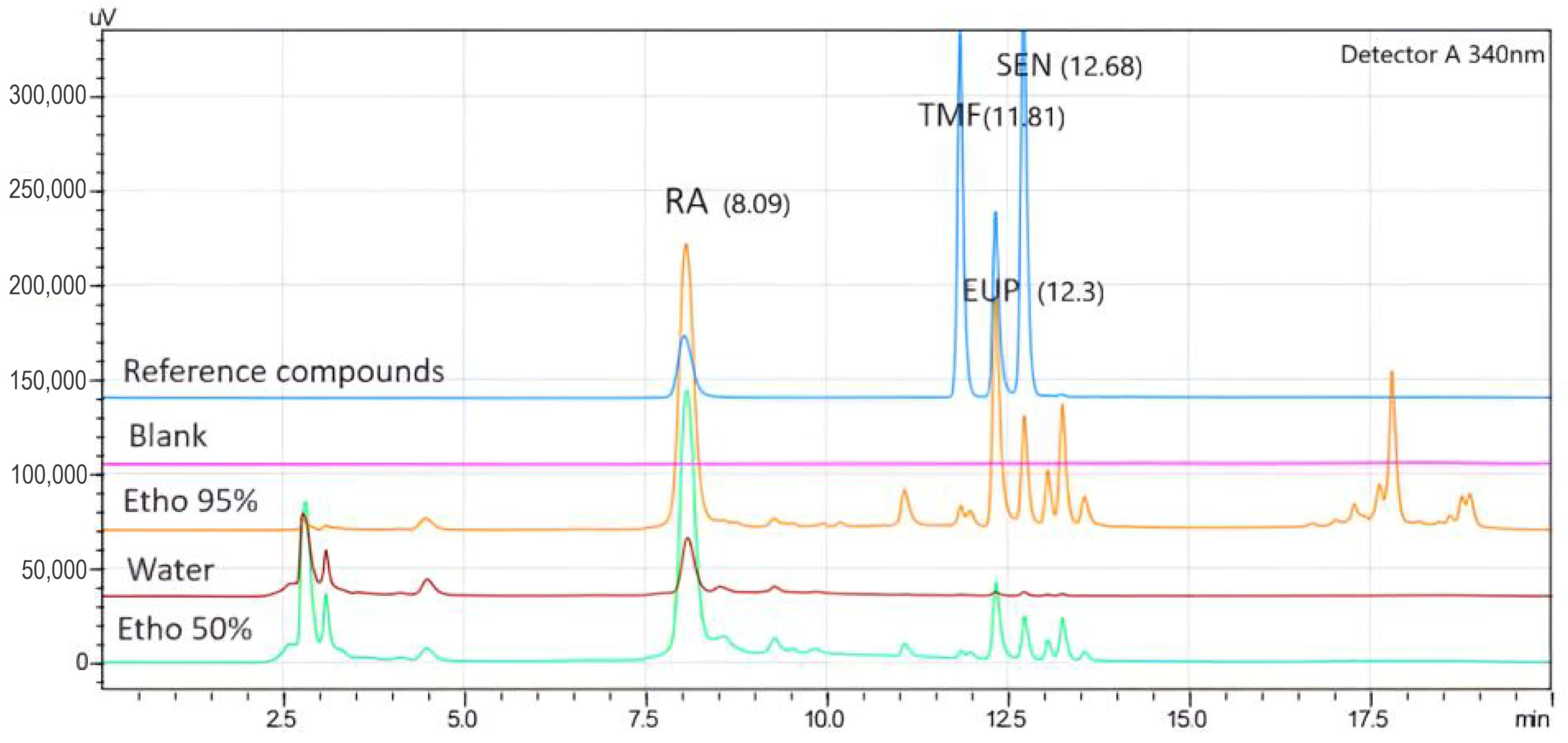

2.1. HPLC Analysis

2.1.1. Selectivity

2.1.2. Linearity

2.1.3. Quantification of RA, TMF, EUP, and SEN from Different OS Extracts

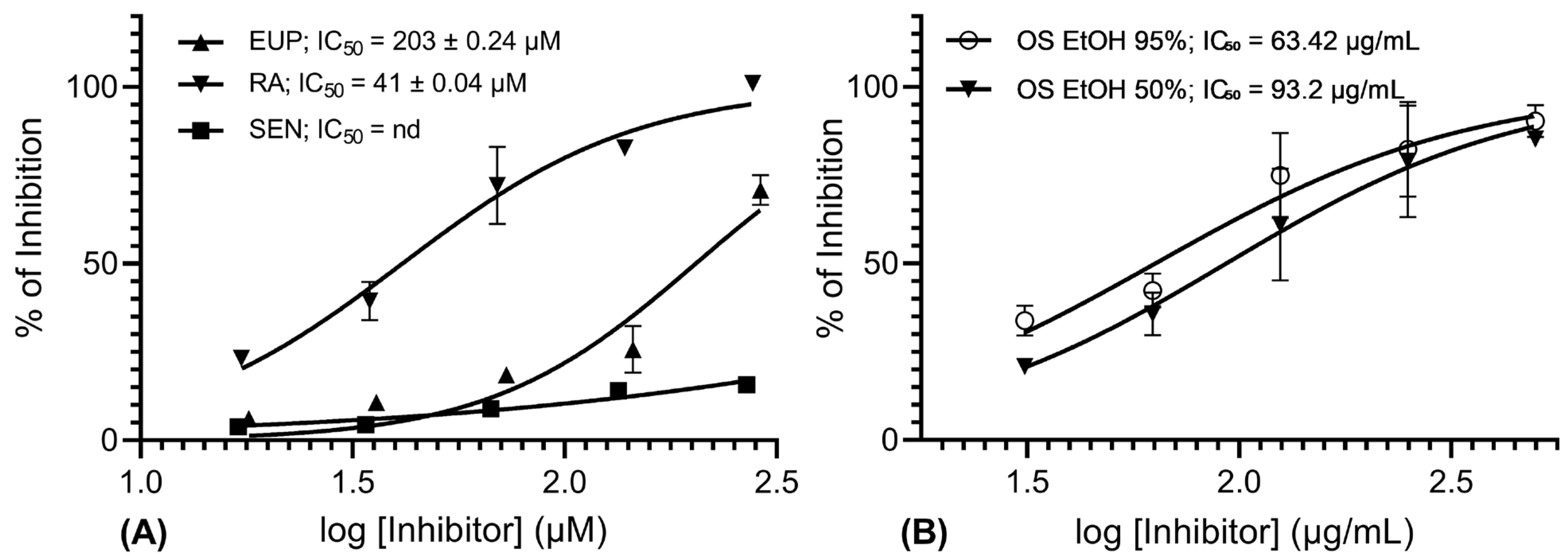

2.2. In Vitro AR Inhibition Assay

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Standard and Sample Preparation

4.3. Identification and Quantification of EUP, RA, SEN, and TMF in OS Extracts

Chromatographic Conditions

4.4. Method Validation

4.4.1. Selectivity

4.4.2. Sensitivity and Linearity

4.4.3. Intra- and Inter-Day Precision and Accuracy

4.4.4. Quantification of EUP, RA, SEN, and TMF from Different OS Extracts

4.5. In Vitro AR Inhibition Assay

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yehya, A.H.; Asif, M.; Kaur, G.; Hassan, L.E.; Al-Suede, F.S.; Majid, A.M.A.; Oon, C.E. Toxicological studies of Orthosiphon stamineus (Misai Kucing) standardized ethanol extract in combination with gemcitabine in athymic nude mice model. J. Adv. Res. 2019, 15, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, C.D.; Gadal, S.; Mhatre, M.; Williamson, K.S.; Pye, Q.N.; Hensley, K. Antioxidants in Central Nervous System Diseases: Preclinical Promise and Translational Challenges. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2008, 15, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amor, S.; Puentes, F.; Baker, D.; Van Der Valk, P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2010, 129, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y.-S.; Choo, B.K.M.; Ahmed, P.K.; Othman, I.; Shaikh, M.F. Orthosiphon stamineus proteins alleviate pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures in Zebrafish. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retinasamy, T.; Shaikh, M.F.; Kumari, Y.; Abidin, S.A.Z.; Othman, I. Orthosiphon stamineus standardized extract reverses streptozotocin-induced alzheimer’s disease-like condition in a rat model. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, O.Z.; Salman, I.M.; Asmawi, M.Z.; Ibraheem, Z.O.; Yam, M.F. Orthosiphon stamineus: Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, M.F.; Asmawi, M.Z.; Basir, R. An investigation of the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of Orthosiphon stamineus leaf extract. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yam, M.F.; Ang, L.F.; Basir, R.; Salman, I.M.; Ameer, O.Z.; Asmawi, M.Z. Evaluation of the anti-pyretic potential of Orthosiphon stamineus Benth standardized extract. Inflammopharmacology 2008, 17, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Ramana, K.V.; Bhatnagar, A. Role of aldose reductase and oxidative damage in diabetes and the consequent potential for therapeutic options. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana, K.V. Aldose reductase: New insights for an old enzyme. Biomol. Concepts 2011, 2, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakunina, N.; Pariante, C.M.; Zunszain, P.A. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression. Immunology 2015, 144, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.K.; Yadav, U.C.; Reddy, A.B.; Saxena, A.; Tammali, R.; Shoeb, M.; Ansari, N.H.; Bhatnagar, A.; Petrash, M.J.; Srivastava, S.; et al. Aldose reductase inhibition suppresses oxidative stress-induced inflammatory disorders. Chem. Interactions 2011, 191, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, A.S.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. Oxidative Stress in Depression: The Link with the Stress Response, Neuroinflammation, Serotonin, Neurogenesis and Synaptic Plasticity. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-K.; Liu, C.-C.; Wang, S.; Cheng, H.-C.; Meadows, C.; Chang, K.-C. The Role of Aldose Reductase in Beta-Amyloid-Induced Microglia Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, A.S.; Thapa, K.; Kanojia, N.; Sharma, N.; Singh, S. Natural Compounds as Source of Aldose Reductase (AR) Inhibitors for the Treatment of Diabetic Complications: A Mini Review. Curr. Drug Metab. 2020, 21, 1091–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, M.T.; Zal, F.; Malakooti, M.; Sadeghian, M.S.S. Inhibitory activity of flavonoids on the lens aldose reductase of healthy and diabetic rats. Acta Med. Iran. 2006, 44, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Ouyang, T.; Xu, A.; Bian, Q.; Zhu, B.; Zhao, M. Quercetin Improves Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Depression by Regulating the Level of Let-7e-5p in Microglia Exosomes. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 2189–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Bioanalytical Method Validation: Guidance for Industry; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, M.; Ismail, Z. Simultaneous analysis of bioactive markers from Orthosiphon stamineus benth leaves extracts by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2011, 10, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Saidan, N.; Aisha, A.; Hamil, M.S.; Majid, A.M.S.A. A novel reverse phase high-performance liquid chromatography method for standardization of Orthosiphon stamineus leaf extracts. Pharmacogn. Res. 2015, 7, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehya, A.H.; Al-Mansoub, M.A.; Al-Suede, F.S.R.; Sultan, S.B.B.S.; Abduraman, M.A.; Azimi, N.A.; Jafari, S.F.; Abdul Majid, A.M.S.B. Anti-tumor Activity of NuvastaticTM (C5OSEW5050ESA) of Orthosiphon stamineus and Rosmarinic Acid in an Athymic Nude Mice Model of Breast Cancer. J. Angiother. 2022, 6, V612–V619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akowuah, G.; Zhari, I.; Norhayati, I.; Sadikun, A.; Khamsah, S. Sinensetin, eupatorin, 3′-hydroxy-5,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone and rosmarinic acid contents and antioxidative effect of Orthosiphon stamineus from Malaysia. Food Chem. 2004, 87, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, S.I.; Mohan, S.; Elhassan, M.M.; Al-Mekhlafi, N.; Mariod, A.A.; Abdul, A.B.; Abdulla, M.A.; Alkharfy, K.M. Antiapoptotic and antioxidant properties of Orthosiphon stamineus benth (Cat’s Whiskers): Intervention in the Bcl-2-mediated apoptotic pathway. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2010, 2011, 156765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzi, N.; Mohd, K.S.; Halim, N.H.A.; Ismail, Z. Orthosiphon stamineus extracts inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in uterine fibroid cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2018, 19, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miláčková, I.; Kapustová, K.; Mučaji, P.; Hošek, J. Artichoke Leaf Extract Inhibits AKR1B1 and Reduces NF-κB Activity in Human Leukemic Cells. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Marker | Quality Control | Level (µg/mL) | Intra-Day (n = 5) | Inter-Day (n = 5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSD% | RE% | RSD% | RE% | |||

| Rosmarinic acid (RA) | LLOQ | 15.62 | 1.79 | −16.86 | 2.07 | −18.35 |

| LQC | 31.25 | 0.09 | −8.35 | 0.06 | −9.47 | |

| MQC | 125 | 0.20 | 4.57 | 0.05 | 4.25 | |

| HQC | 250 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 1.38 | −1.15 | |

| 3′-hydroxy-5,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone (TMF) | LLOQ | 1.95 | 2.09 | 18.21 | 2.80 | 20.26 |

| LQC | 15.62 | 0.77 | −0.10 | 1.17 | −0.22 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | 0.18 | −2.40 | 1.75 | −1.60 | |

| HQC | 125 | 0.63 | 1.55 | 0.91 | 1.27 | |

| Eupatorin (EUP) | LLOQ | 1.95 | 3.75 | −2.14 | 3.04 | 1.35 |

| LQC | 15.62 | 0.61 | 2.64 | 1.11 | 2.85 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | 0.77 | 1.04 | 1.62 | 1.03 | |

| HQC | 125 | 1.05 | 1.82 | 0.78 | 1.82 | |

| Sinensetin (SEN) | LLOQ | 1.95 | 3.00 | −1.21 | 2.43 | 9.29 |

| LQC | 15.62 | 0.69 | 14.89 | 1.32 | 15.88 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | 0.20 | 8.59 | 1.42 | 6.95 | |

| HQC | 125 | 0.59 | −7.04 | 1.01 | −7.60 | |

| Content % (w/w) ± SD (n = 5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract | RA | TMF | EUP | SEN |

| 95% ethanolic | 11.91 ± 0.75 | 0.18 ± 0.019 | 2.35 ± 0.040 | 0.94 ± 0.050 |

| 50% ethanolic | 10.60 ± 0.11 | 0.05 ± 0.021 | 0.84 ± 0.014 | 0.32 ± 0.009 |

| Water | 2.38 ± 0.07 | nd | 0.03 ± 0.003 | nd |

| Time | Solvent Ratio (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Phosphate Buffer | (B) Acetonitrile | (C) Methanol | |

| 0 | 80 | 10 | 10 |

| 5 | 50 | 30 | 20 |

| 10 | 20 | 25 | 55 |

| 12 | 0 | 30 | 70 |

| 15 | 45 | 15 | 40 |

| 18 | 80 | 10 | 10 |

| 20 | 80 | 10 | 10 |

| Markers | Level | Concentration of Standard (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Rosmarinic acid | LLOQ | 15.62 |

| LQC | 31.25 | |

| MQC | 125 | |

| HQC | 250 | |

| 3′-hydroxy-5,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone | LLOQ | 1.95 |

| LQC | 15.62 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | |

| HQC | 125 | |

| Eupatorin | LLOQ | 1.95 |

| LQC | 15.62 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | |

| HQC | 125 | |

| Sinensetin | LLOQ | 1.95 |

| LQC | 15.62 | |

| MQC | 31.25 | |

| HQC | 125 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dawood, Y.; Zgair, A.; Yam, M.F.; Abdul Aziz, N.H.K. Aldose Reductase Inhibition by Orthosiphon stamineus Extracts and Constituents Suggests Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234637

Dawood Y, Zgair A, Yam MF, Abdul Aziz NHK. Aldose Reductase Inhibition by Orthosiphon stamineus Extracts and Constituents Suggests Antioxidant Potential. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234637

Chicago/Turabian StyleDawood, Yousaf, Atheer Zgair, Mun Fei Yam, and Nur Hidayah Kaz Abdul Aziz. 2025. "Aldose Reductase Inhibition by Orthosiphon stamineus Extracts and Constituents Suggests Antioxidant Potential" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234637

APA StyleDawood, Y., Zgair, A., Yam, M. F., & Abdul Aziz, N. H. K. (2025). Aldose Reductase Inhibition by Orthosiphon stamineus Extracts and Constituents Suggests Antioxidant Potential. Molecules, 30(23), 4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234637