SERAAK2 as a Serotonin Receptor Ligand: Structural and Pharmacological In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

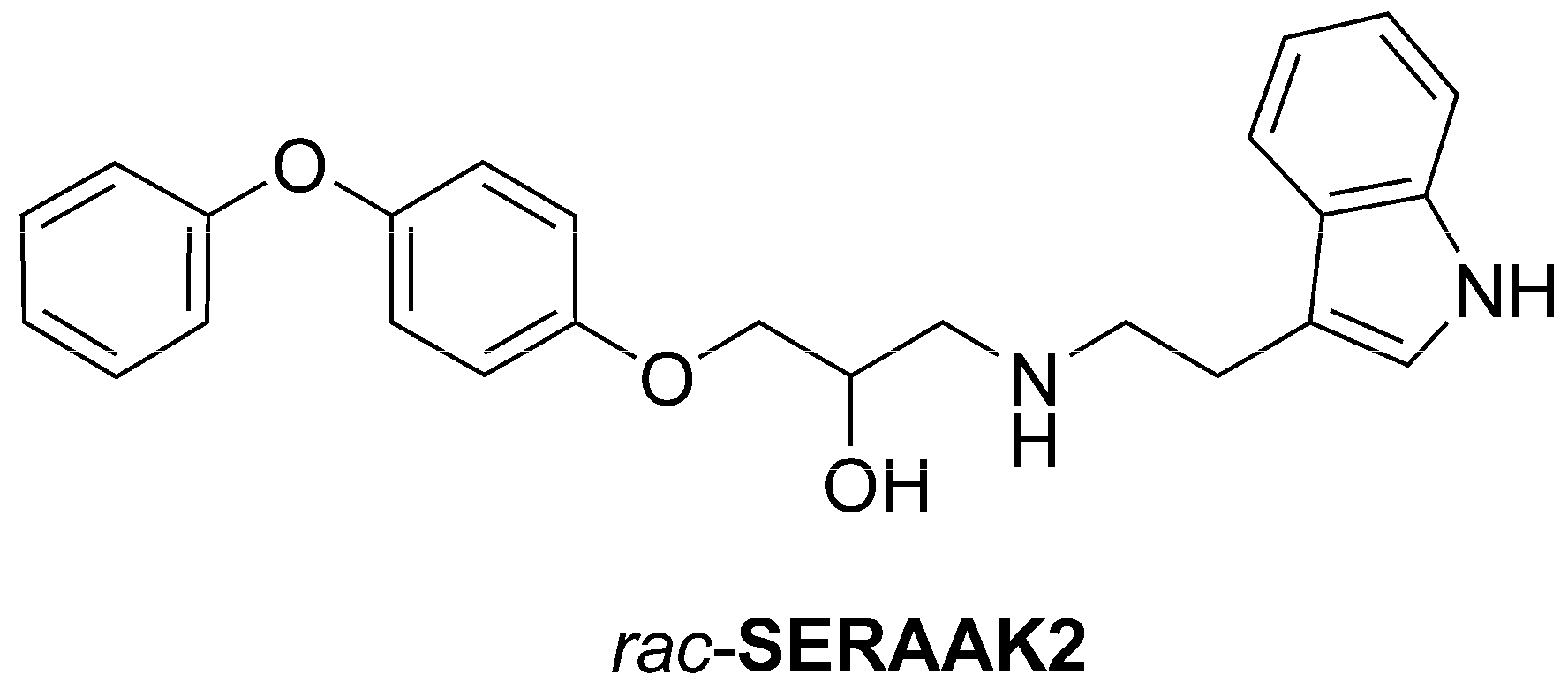

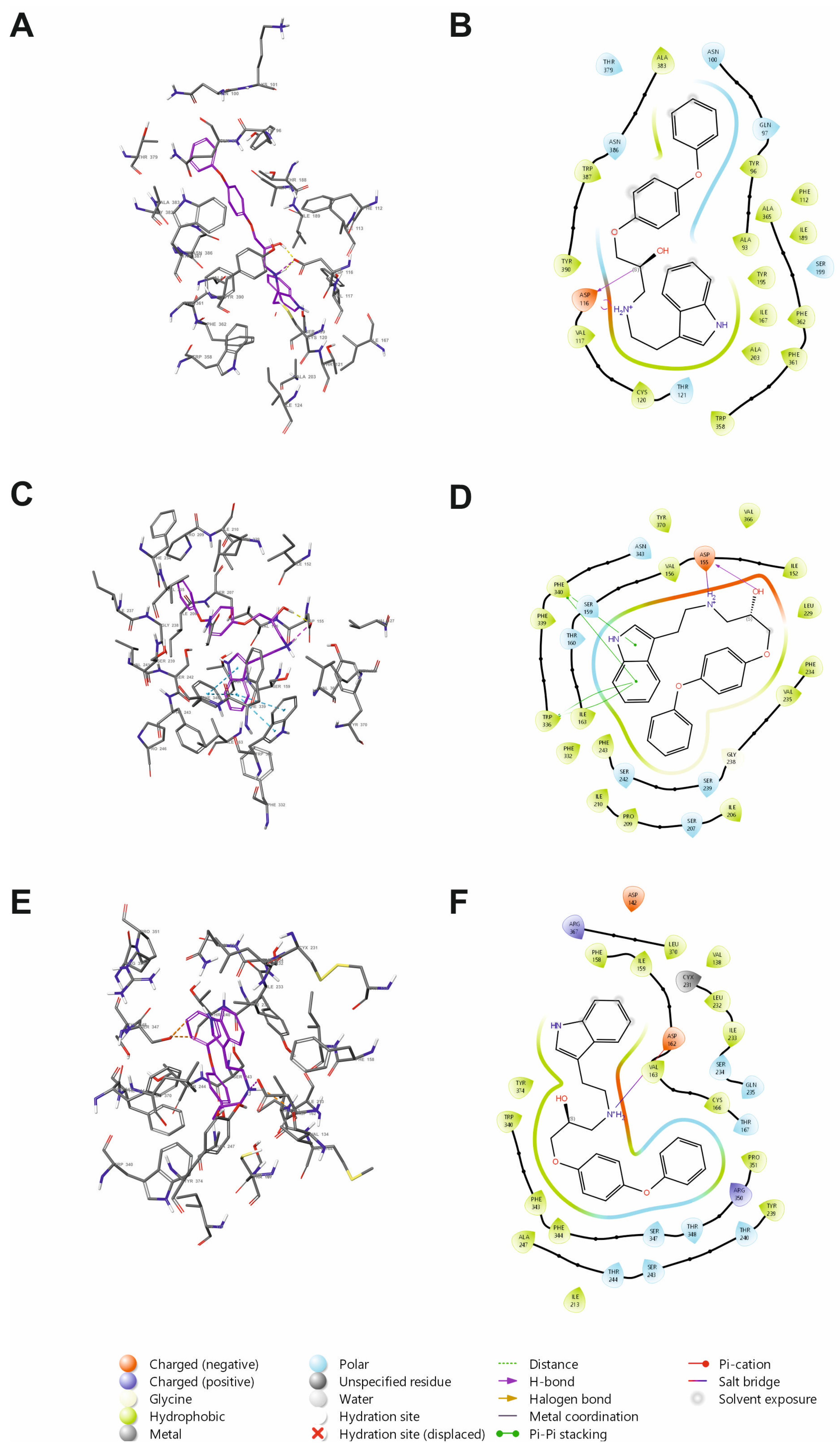

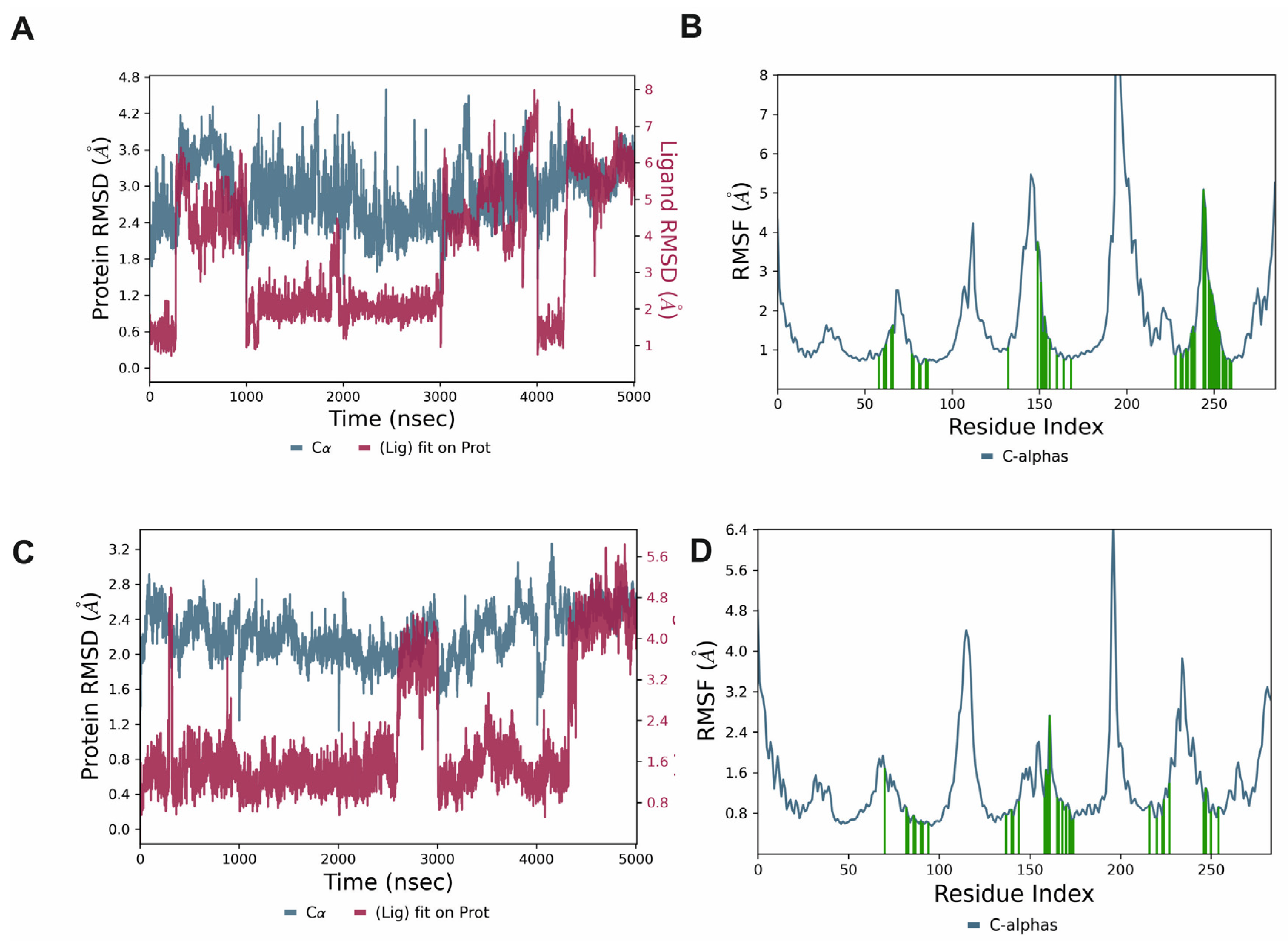

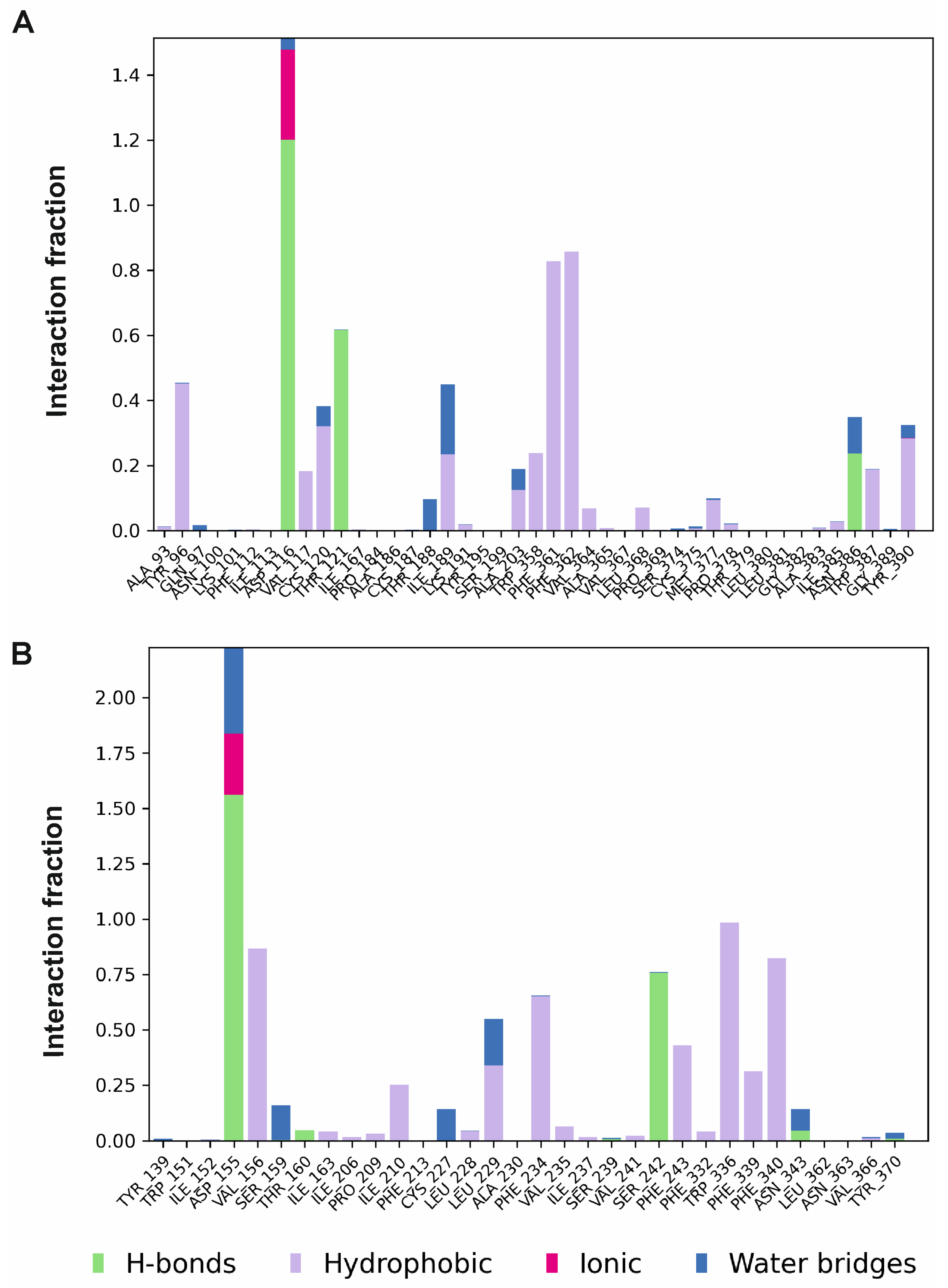

2.1. In Silico Studies

2.1.1. Molecular Docking

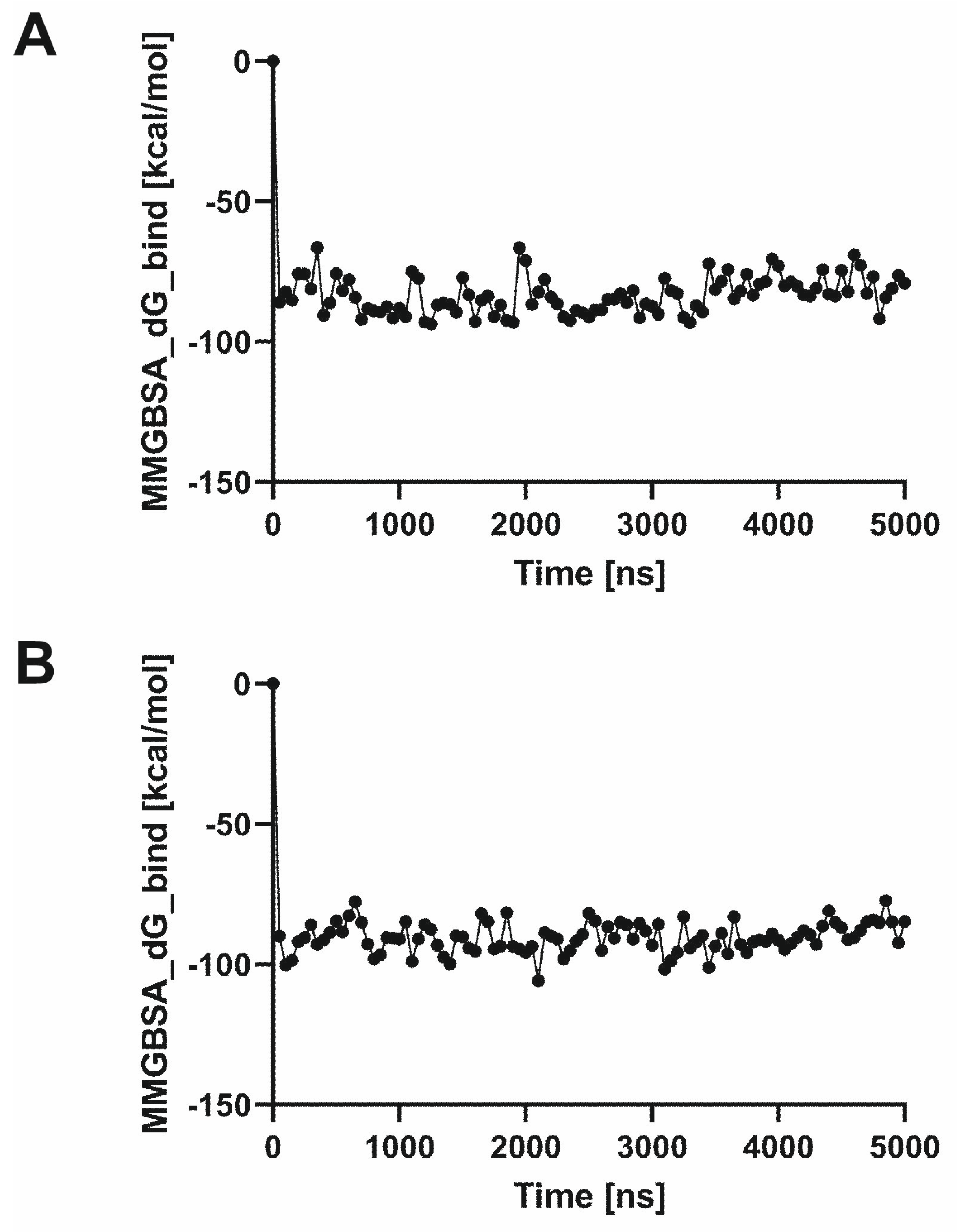

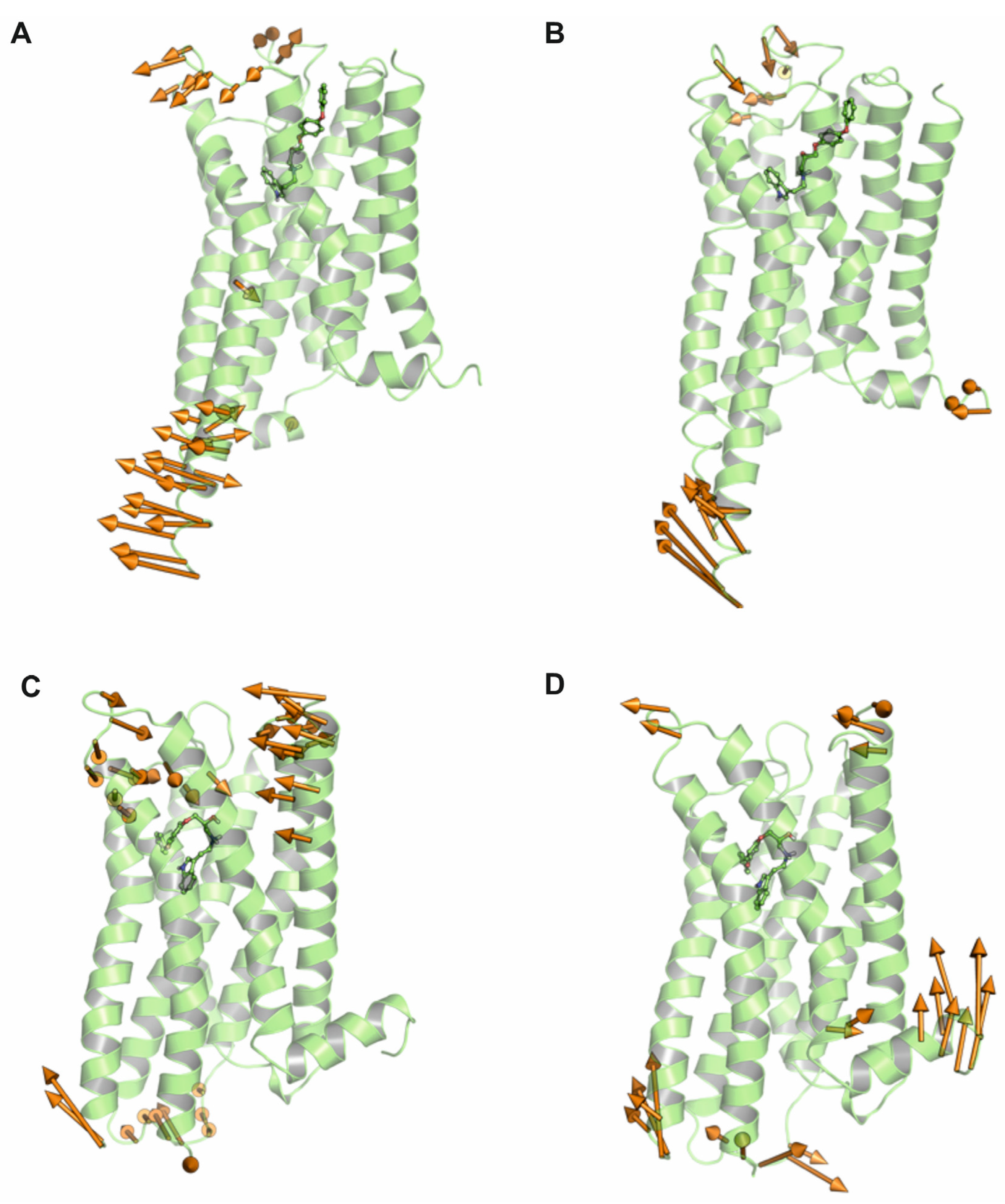

2.1.2. Molecular Dynamics Simulations

2.2. ADMET Evaluation of SERAAK2

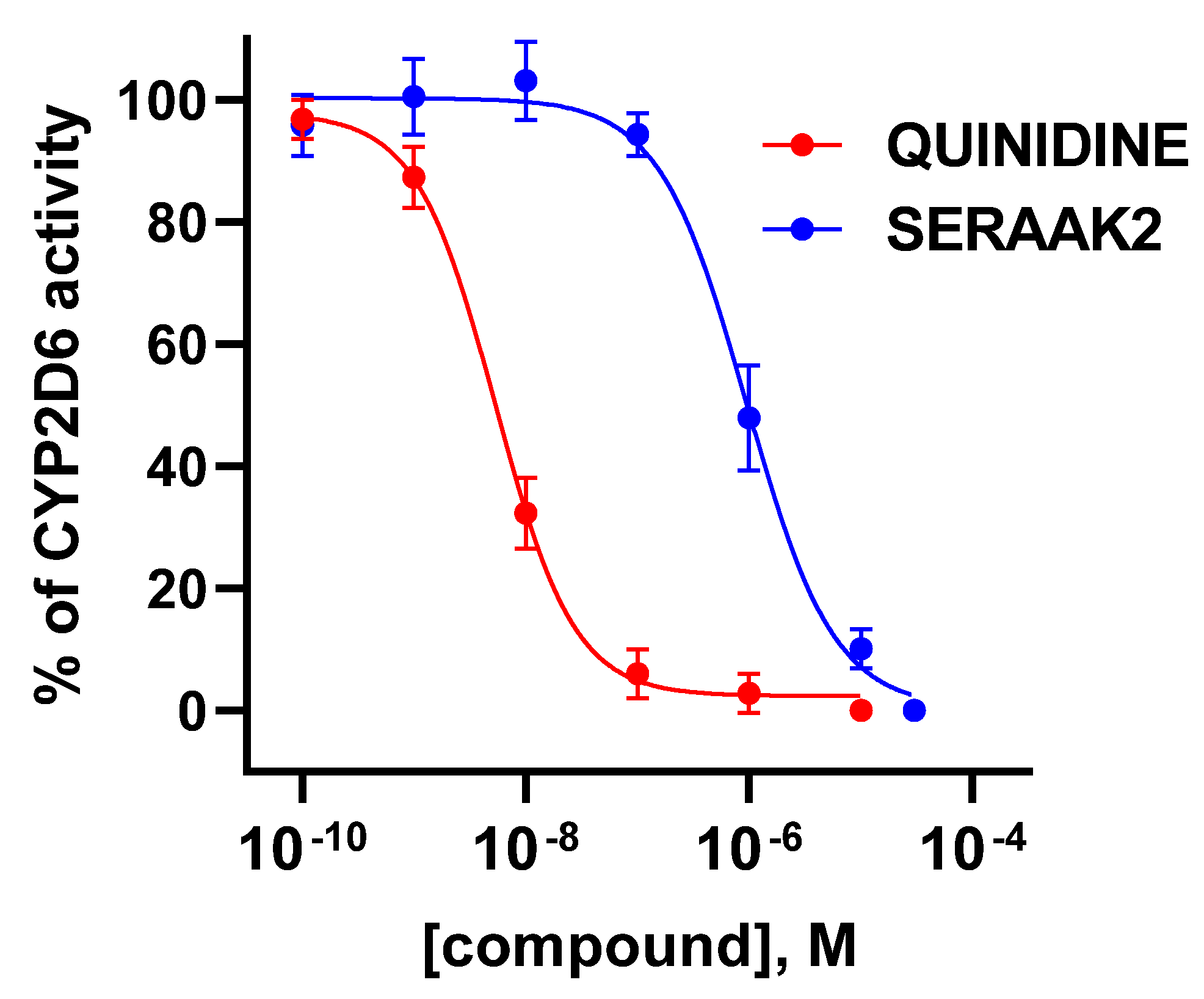

2.2.1. Cytochrome P450 Enzymatic Activity

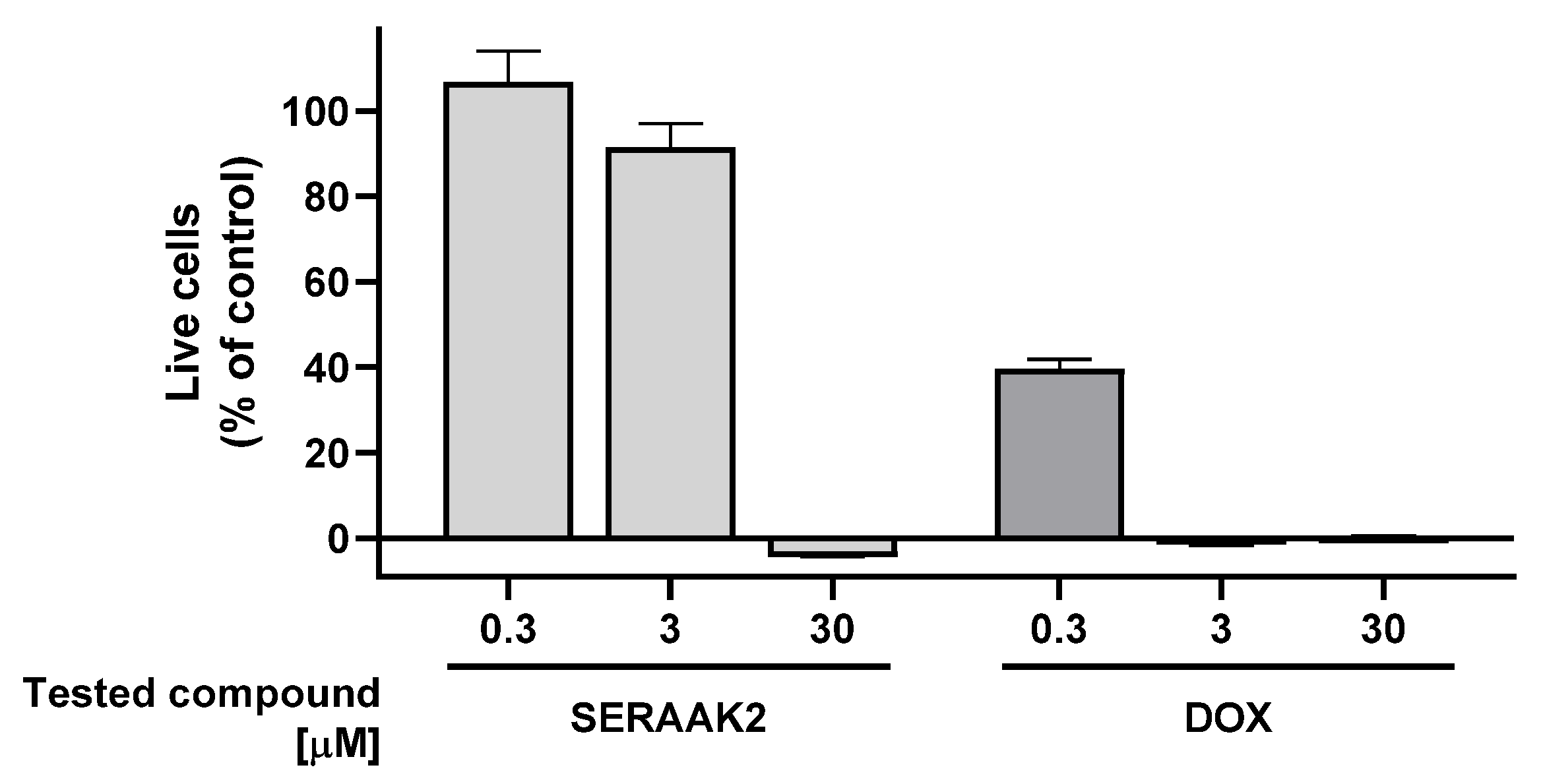

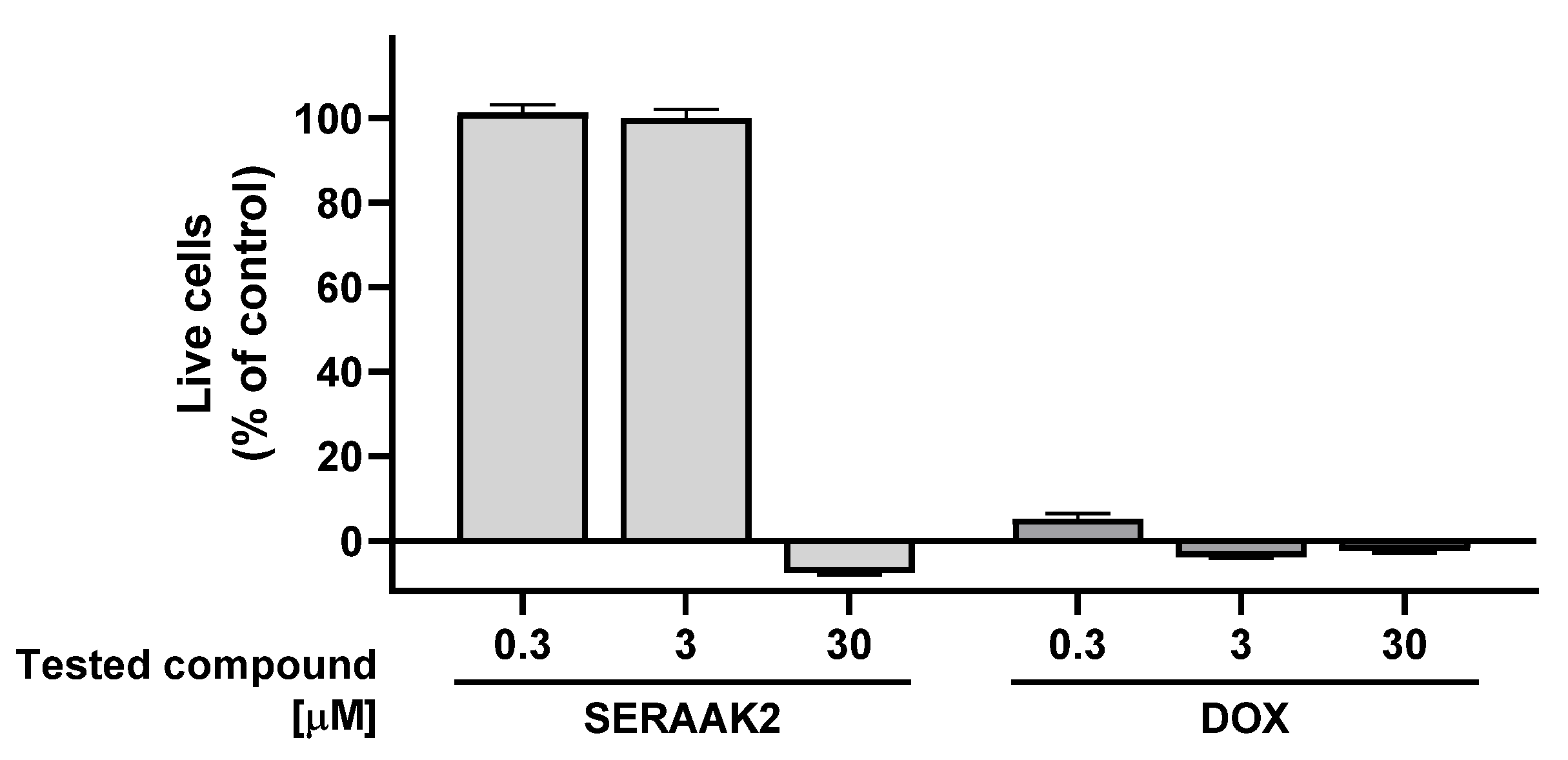

2.2.2. Cell Cytotoxicity

2.2.3. Membrane Permeability

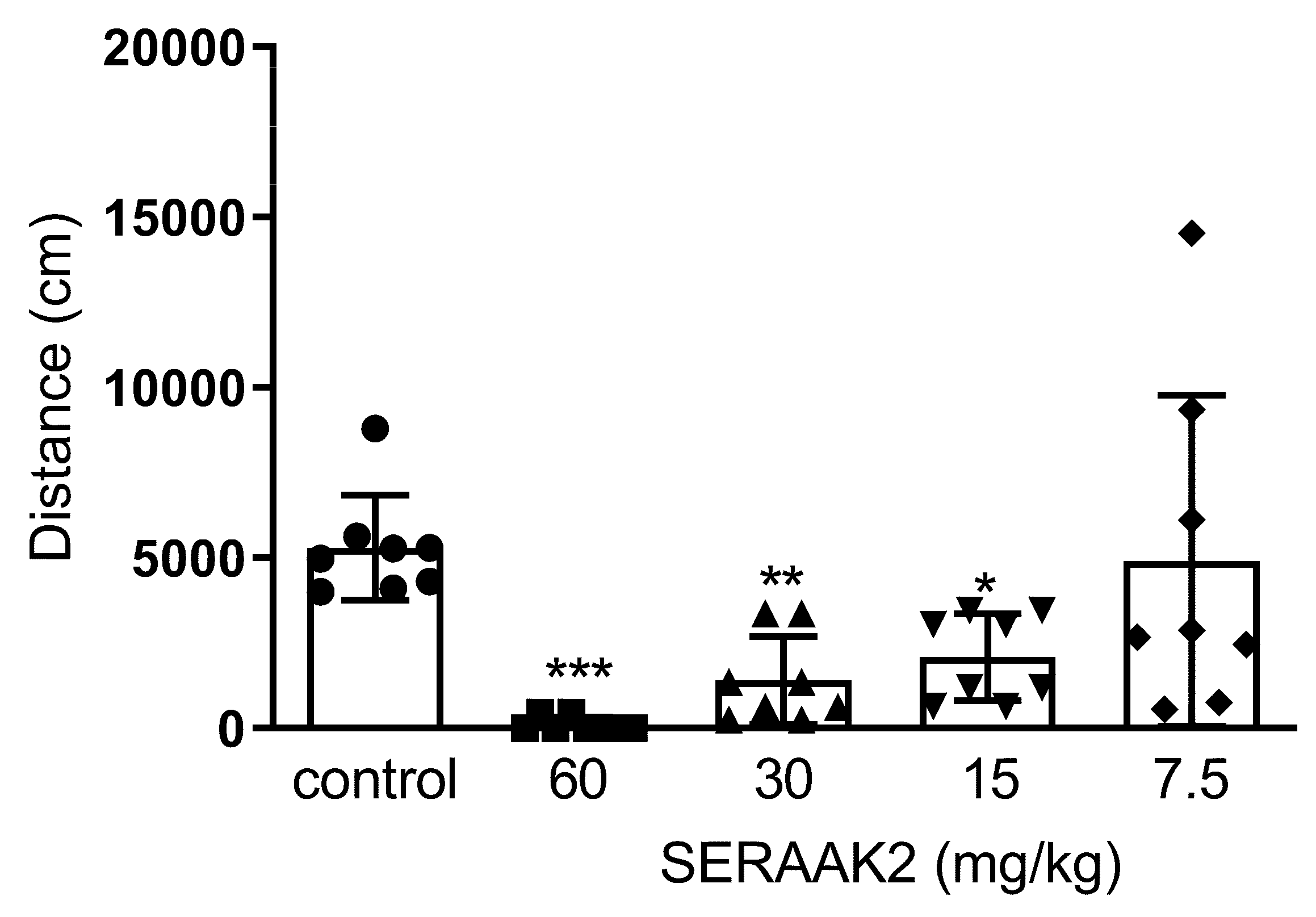

2.3. Behavioral Studies

2.3.1. Spontaneous Locomotor Activity

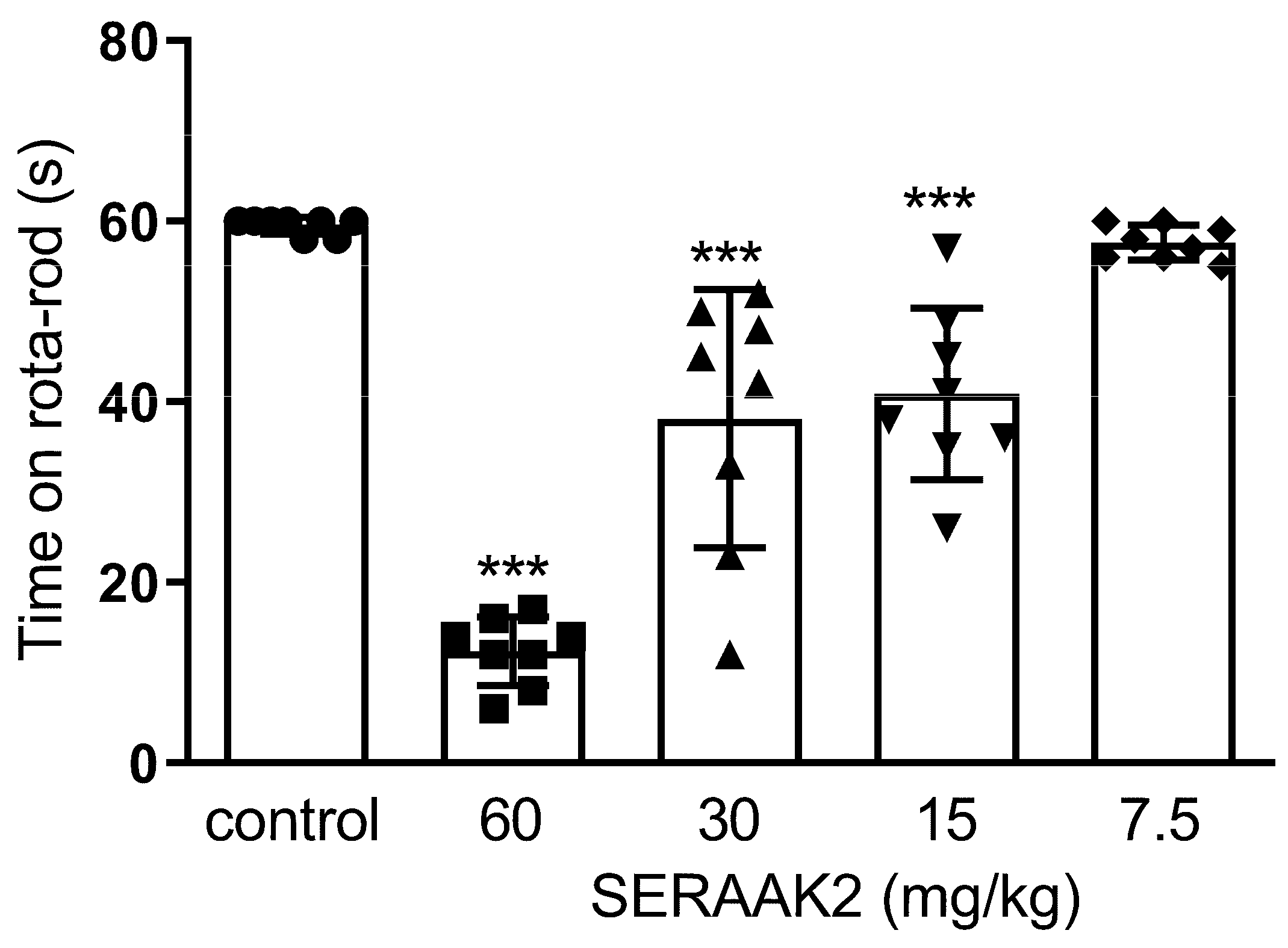

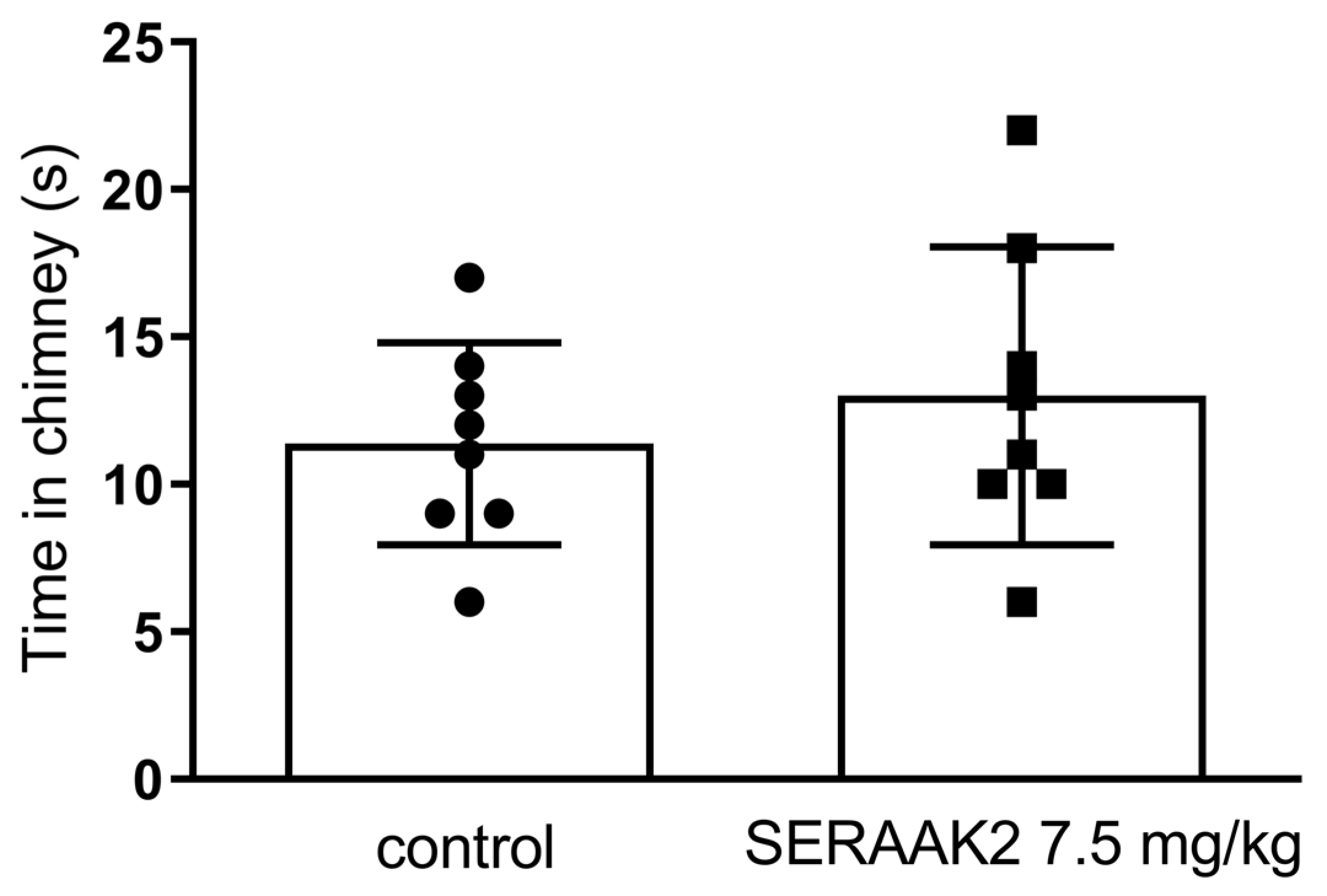

2.3.2. Motor Coordination

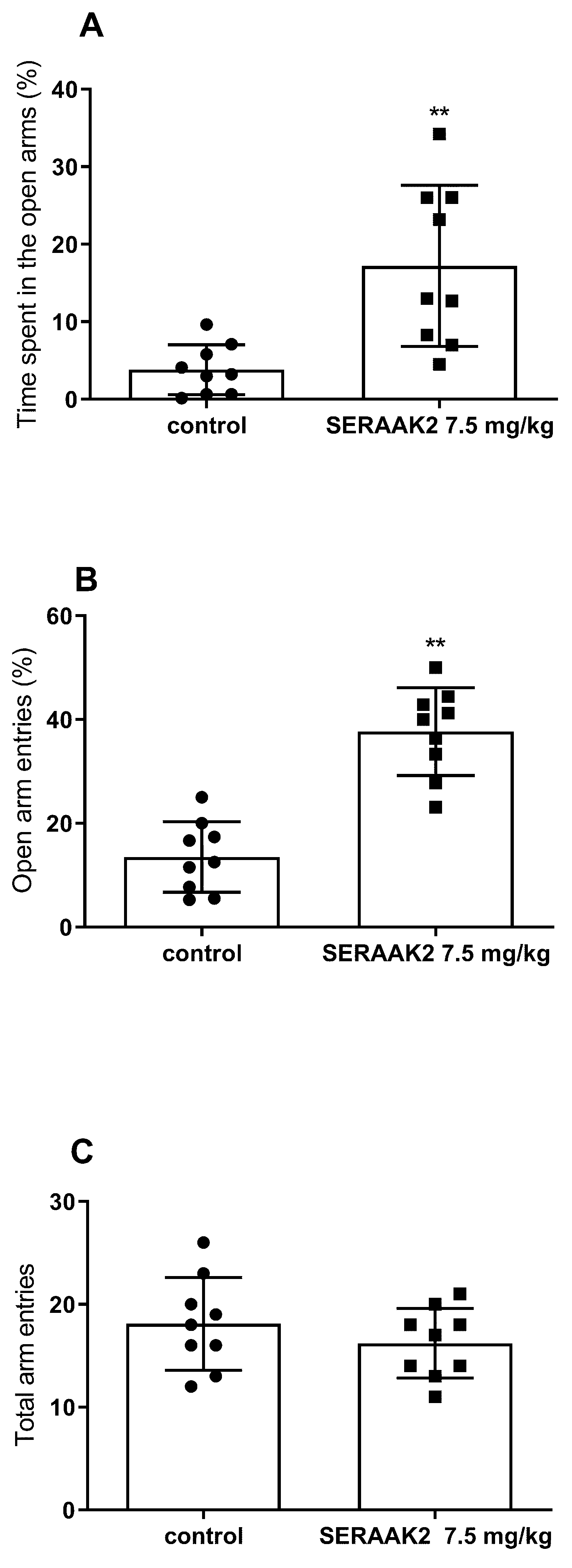

2.3.3. Effect of Acute Administration of SERAAK2 (7.5 mg/kg) on Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) Performance in Mice

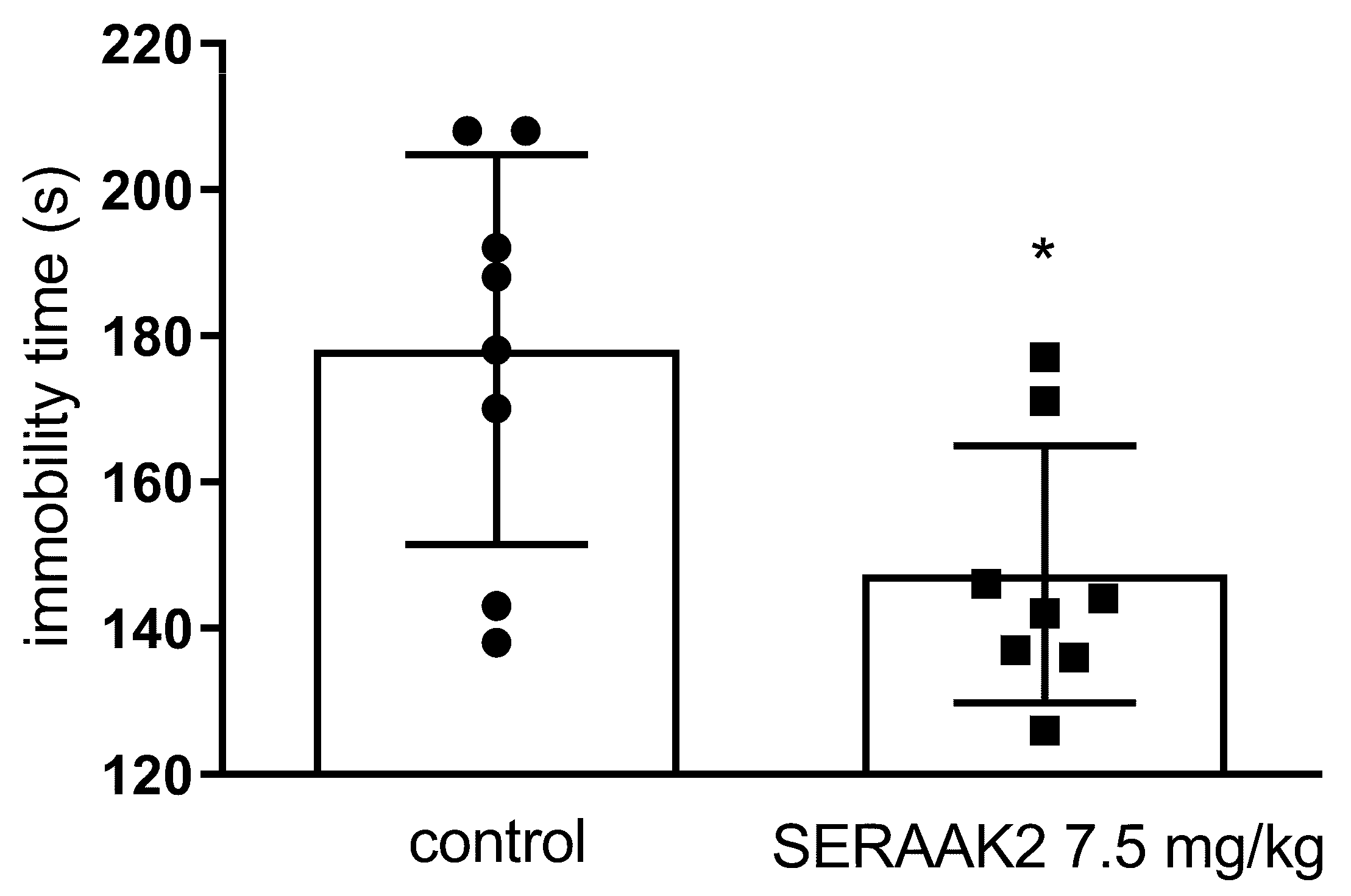

2.3.4. Effect of Acute Administration of SERAAK2 (7.5 mg/kg) on the Total Duration of Immobility in the Forced Swim Test (FST) in Mice

2.3.5. Effect of Acute Administration of SERAAK2 (7.5 mg/kg) on Memory Consolidation in the Passive Avoidance (PA) Test in Mice

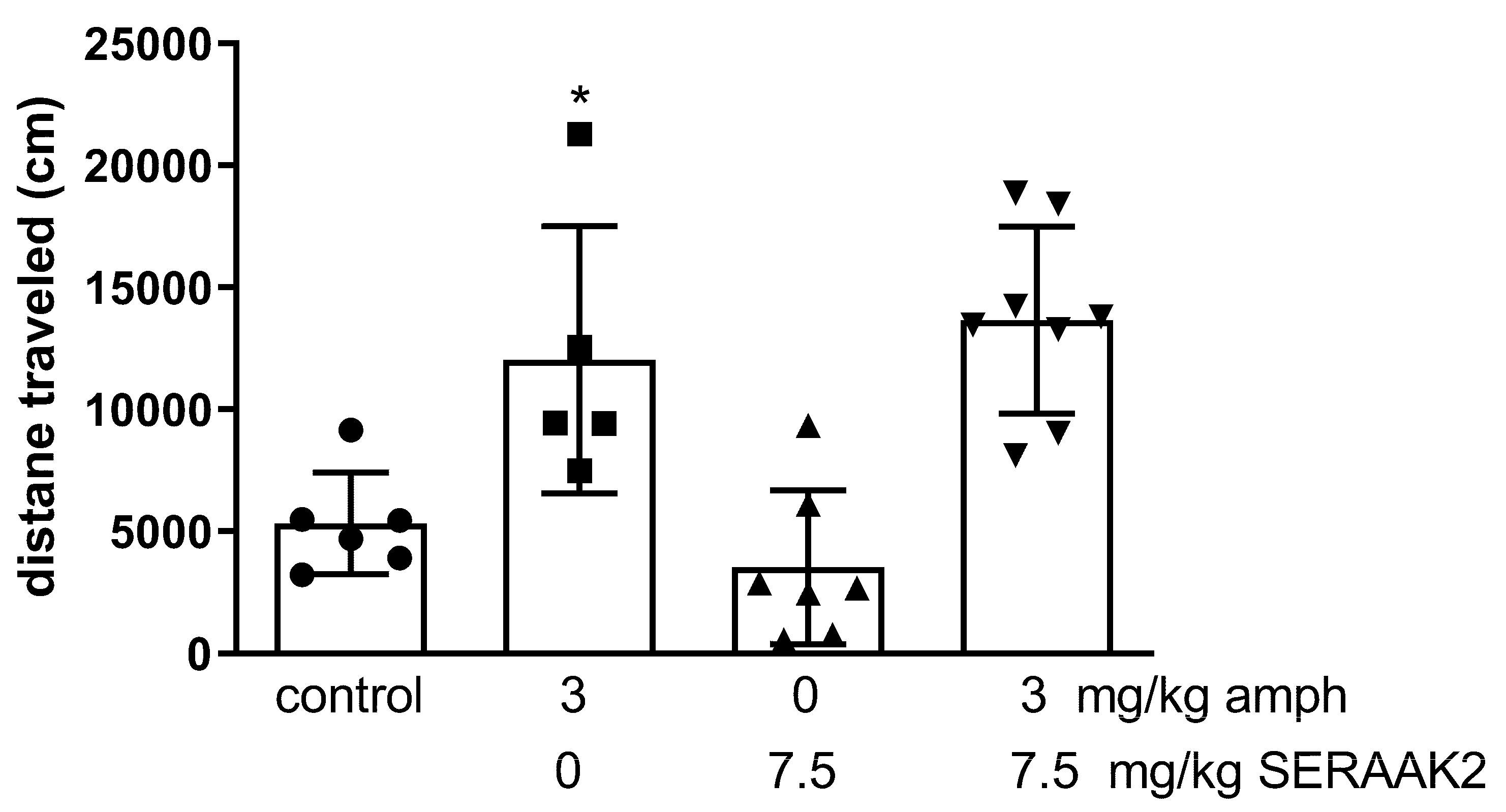

2.3.6. Amphetamine-Induced Hyperactivity in Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. In Silico Studies

4.2. ADMET Studies

4.2.1. Assessment of Cytochrome P450 Enzymatic Activity

4.2.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment

4.2.3. Membrane Permeability Assessment

4.3. Behavioral Studies

4.3.1. Animals

- Spontaneous locomotor activity test—five groups (n = 8 per group): the control group received vehicle only, and four groups received the tested compound at doses of 7.5, 15, 30, or 60 mg/kg.

- Rotarod test—same group design as above (five groups, n = 8 per group).

- Chimney test,

- FST

- PA—two groups (n = 8 per group): control and the group receiving the compound at 7.5 mg/kg.

- Elevated plus maze test—two groups (n = 9 per group): control and the group receiving the compound at 7.5 mg/kg.

- Amphetamine-induced hyperactivity test—four groups (n = 8 per group): vehicle control, amphetamine only, tested compound at a dose of 7.5 mg/kg, and the combination of amphetamine and the tested compound.

4.3.2. Experiments

4.3.3. Drugs

4.3.4. Spontaneous Locomotor Activity and Amphetamine-Induced Hyperactivity

4.3.5. Motor Coordination

4.3.6. Elevated Plus Maze Test (EPM Test)

4.3.7. Forced Swim Test (FST, Porsolt’s Test) in Mice

4.3.8. Passive Avoidance Task

4.3.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity |

| EPM | Elevated plus maze test |

| FST | Forced swim test |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| MTS | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-Tetrazolium |

| PA | Passive avoidance test |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| RMSF | Root mean square fluctuation |

| SPC | Simple point charge |

References

- Li, Y.; Jönsson, L. The Health and Economic Burden of Brain Disorders: Consequences for Investment in Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and R&D. Cereb. Circ. Cogn. Behav. 2025, 8, 100377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, A.A.N.; Imani, A.; Farahbakhsh, M.; Sarbakhsh, P. Economic Burden of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Panic Anxiety, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). J. Ment. Health Policy Econ. 2025, 28, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.; Knapp, M.; Catty, J.; Healey, A.; Henderson, J.; Watt, H.; Wright, C. Home Treatment for Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. Health Technol. Assess. 2001, 5, 1–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zięba, A.; Bartuzi, D.; Stępnicki, P.; Matosiuk, D.; Wróbel, T.M.; Laitinen, T.; Castro, M.; Kaczor, A.A. Discovery and in Vitro Evaluation of Novel Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptor Ligands Identified Through Virtual Screening. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba, A.; Kędzierska, E.; Jastrzębski, M.K.; Karcz, T.; Olejarz-Maciej, A.; Sumara, A.; Laitinen, T.; Wróbel, T.M.; Fornal, E.; Castro, M.; et al. Synthesis, Experimental and Computational Evaluation of SERAAK1 as a 5-HT2A Receptor Ligand. Molecules 2025, 30, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Huang, S.; Zhang, H.; Mao, C.; Zhou, X.E.; Cheng, X.; Simon, I.A.; Shen, D.-D.; Yen, H.-Y.; Robinson, C.V.; et al. Structural Insights into the Lipid and Ligand Regulation of Serotonin Receptors. Nature 2021, 592, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, K.T.; Asada, H.; Inoue, A.; Kadji, F.M.N.; Im, D.; Mori, C.; Arakawa, T.; Hirata, K.; Nomura, Y.; Nomura, N.; et al. Structures of the 5-HT2A Receptor in Complex with the Antipsychotics Risperidone and Zotepine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019, 26, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Xu, P.; Shen, D.-D.; Simon, I.A.; Mao, C.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, H.; Harpsøe, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; et al. GPCRs Steer Gi and Gs Selectivity via TM5-TM6 Switches as Revealed by Structures of Serotonin Receptors. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2681–2695.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almaula, N.; Ebersole, B.J.; Zhang, D.; Weinstein, H.; Sealfon, S.C. Mapping the Binding Site Pocket of the Serotonin 5-Hydroxytryptamine2A Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 14672–14675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vass, M.; Podlewska, S.; De Esch, I.J.P.; Bojarski, A.J.; Leurs, R.; Kooistra, A.J.; De Graaf, C. Aminergic GPCR–Ligand Interactions: A Chemical and Structural Map of Receptor Mutation Data. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 3784–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Kerns, E.H. Drug-Like Properties: Concepts, Structure Design and Methods; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-12-369520-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Murawski, A.; Patel, K.; Crespi, C.L.; Balimane, P.V. A Novel Design of Artificial Membrane for Improving the PAMPA Model. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondej, M.; Wróbel, T.M.; Silva, A.G.; Stępnicki, P.; Koszła, O.; Kędzierska, E.; Bartyzel, A.; Biała, G.; Matosiuk, D.; Loza, M.I.; et al. Synthesis, Pharmacological and Structural Studies of 5-Substituted-3-(1-Arylmethyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridin-4-Yl)-1H-Indoles as Multi-Target Ligands of Aminergic GPCRs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 180, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondej, M.; Wróbel, T.M.; Targowska-Duda, K.M.; Leandro Martínez, A.; Koszła, O.; Stępnicki, P.; Zięba, A.; Paz, A.; Wronikowska-Denysiuk, O.; Loza, M.I.; et al. Multitarget Derivatives of D2AAK1 as Potential Antipsychotics: The Effect of Substitution in the Indole Moiety. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczor, A.A.; Kędzierska, E.; Wróbel, T.M.; Grudzińska, A.; Pawlak, A.; Laitinen, T.; Bartyzel, A. Synthesis, Structural and Behavioral Studies of Indole Derivatives D2AAK5, D2AAK6 and D2AAK7 as Serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A Receptor Ligands. Molecules 2023, 28, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.G. (Ed.) Drug Discovery and Evaluation: Pharmacological Assays; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; p. 565. [Google Scholar]

- Ari, C.; D’Agostino, D.P.; Diamond, D.M.; Kindy, M.; Park, C.; Kovács, Z. Elevated Plus Maze Test Combined with Video Tracking Software to Investigate the Anxiolytic Effect of Exogenous Ketogenic Supplements. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, e58396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garakani, A.; Murrough, J.W.; Freire, R.C.; Thom, R.P.; Larkin, K.; Buono, F.D.; Iosifescu, D.V. Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment Options. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 595584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eison, A.S.; Temple, D.L. Buspirone: Review of Its Pharmacology and Current Perspectives on Its Mechanism of Action. Am. J. Med. 1986, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partyka, A.; Jarosz, J.; Wasik, A.; Jastrzębska-Więsek, M.; Zagórska, A.; Pawłowski, M.; Wesołowska, A. Novel Tricyclic [2,1-f]Theophylline Derivatives of LCAP with Activity in Mouse Models of Affective Disorders. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsolt, R.D.; Le Pichon, M.; Jalfre, M. Depression: A New Animal Model Sensitive to Antidepressant Treatments. Nature 1977, 266, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.C.; Loft, H.; Florea, I.; McIntyre, R.S. Efficacy of Vortioxetine in Working Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yao, K.; Repasky, M.P.; Leswing, K.; Abel, R.; Shoichet, B.K.; Jerome, S.V. Efficient Exploration of Chemical Space with Docking and Deep Learning. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2021, 17, 7106–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger Release 2021-4: Desmond Molecular Dynamics System, D.E. Shaw Research, New York, NY, 2021; Maestro-Desmond Interoperability Tools; Schrödinger: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Ylilauri, M.; Pentikäinen, O.T. MMGBSA as a Tool to Understand the Binding Affinities of Filamin-Peptide Interactions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2013, 53, 2626–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, F.; Tripod, J.; Meier, R. Pharmacological characteristics of the soporific doriden. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1955, 85, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boissier, J.-R.; Tardy, J.; Diverres, J.-C. Une Nouvelle Méthode Simple Pour Explorer l’action «tranquillisante»: Le Test de La Cheminée. Med. Exp. 1960, 3, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, R.G. The Use of a Plus-Maze to Measure Anxiety in the Mouse. Psychopharmacology 1987, 92, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsolt, R.D.; Anton, G.; Blavet, N.; Jalfre, M. Behavioural Despair in Rats: A New Model Sensitive to Antidepressant Treatments. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1978, 47, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venault, P.; Chapouthier, G.; de Carvalho, L.P.; Simiand, J.; Morre, M.; Dodd, R.H.; Rossier, J. Benzodiazepine Impairs and Beta-Carboline Enhances Performance in Learning and Memory Tasks. Nature 1986, 321, 864–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Examined Compound | CYP3A4 Activity Inhibition, Evaluated at the Concentration of 10 µM [% of Inhibition ± SEM] |

|---|---|

| Ketoconazole | 100 ± 1 |

| SERAAK2 | 0 ± 2 |

| Examined Compound | CYP2D6 Activity Inhibition, Evaluated in the Concentration of 10 µM [% of Inhibition ± SEM] |

|---|---|

| Quinidine | 100 ± 1 |

| SERAAK2 | 90 ± 1 |

| Examined Compound | Percentage Reduction in the Number of Viable HepG2 Cells [Mean ± SEM] | Percentage Reduction in the Number of Viable SH-SY5Y Cells [Mean ± SEM] |

|---|---|---|

| SERAAK2 | 104 ± 1 | 108 ± 1 |

| DOX | 100 ± 1 | 102 ± 1 |

| Examined Compound | Pe ± SD [×10−6 cm/s] |

|---|---|

| Caffeine | 12.4 ± 0.6 |

| Sulpiride | 0.011 ± 0.002 |

| SERAAK2 | 1.10 ± 0.35 |

| Test | SERAAK1 | SERAAK2 |

|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous locomotor activity | no change (30–60 mg/kg) |

|

| Motor coordination (rotarod, chimney) | no impairment (30–60 mg/kg)—stable motor profile |

|

| Elevated plus maze (EPM) | ↑ open arm time and entries (30 mg/kg)—anxiolytic effect | ↑ open arm time and entries (7.5 mg/kg)—anxiolytic effect |

| Forced swim test (FST) | ↓ immobility (30 mg/kg)—antidepressant-like effect connected with serotonergic modulation | ↓ immobility (7.5 mg/kg) antidepressant-like effect connected with serotonergic modulation |

| Passive avoidance (PA) | no data | no effect on memory consolidation |

| Amphetamine-induced hyperactivity | ↓ hyperactivity (30 mg/kg) | no effect |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaczor, A.A.; Zięba, A.; Karcz, T.; Jastrzębski, M.K.; Szczepańska, K.; Laitinen, T.; Castro, M.; Kędzierska, E. SERAAK2 as a Serotonin Receptor Ligand: Structural and Pharmacological In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4633. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234633

Kaczor AA, Zięba A, Karcz T, Jastrzębski MK, Szczepańska K, Laitinen T, Castro M, Kędzierska E. SERAAK2 as a Serotonin Receptor Ligand: Structural and Pharmacological In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4633. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234633

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaczor, Agnieszka A., Agata Zięba, Tadeusz Karcz, Michał K. Jastrzębski, Katarzyna Szczepańska, Tuomo Laitinen, Marián Castro, and Ewa Kędzierska. 2025. "SERAAK2 as a Serotonin Receptor Ligand: Structural and Pharmacological In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4633. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234633

APA StyleKaczor, A. A., Zięba, A., Karcz, T., Jastrzębski, M. K., Szczepańska, K., Laitinen, T., Castro, M., & Kędzierska, E. (2025). SERAAK2 as a Serotonin Receptor Ligand: Structural and Pharmacological In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Molecules, 30(23), 4633. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234633