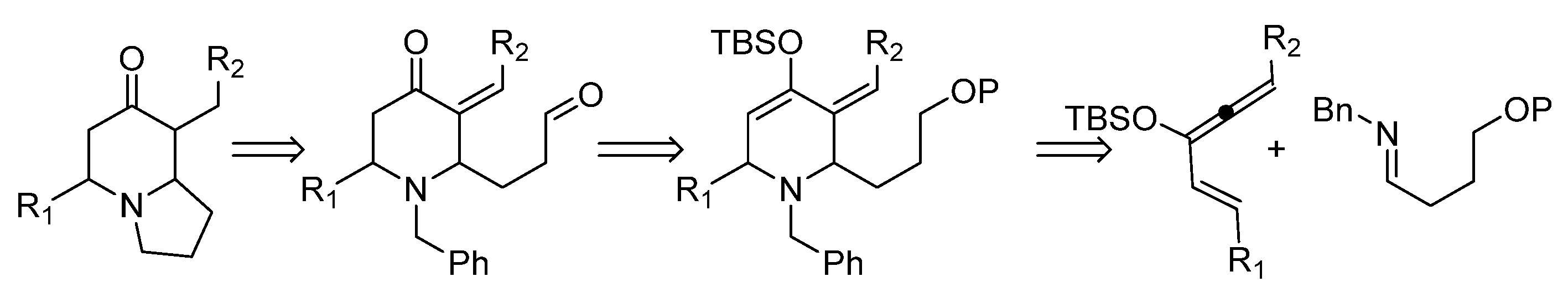

3.2. Compound Synthesis

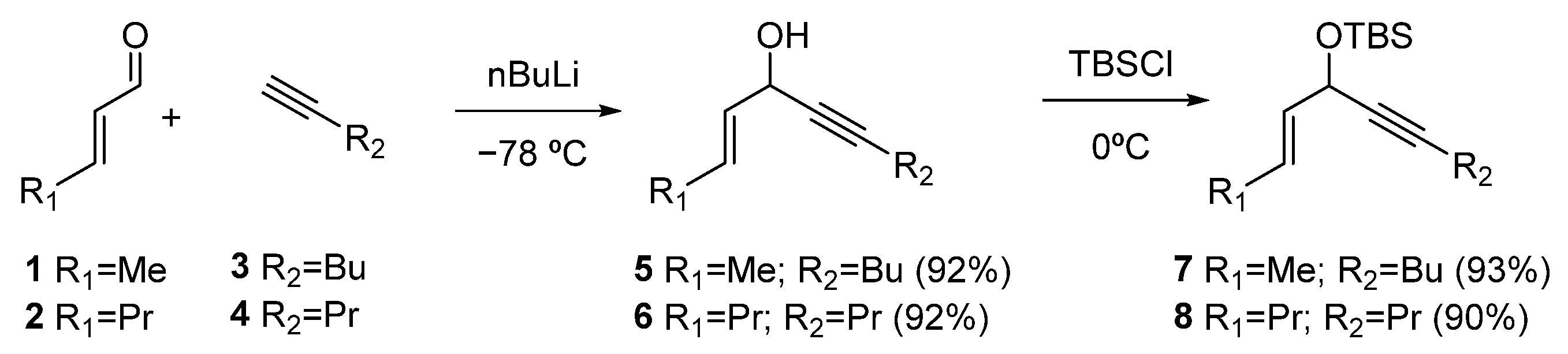

Synthesis of rac-(E)-dec-2-en-5-yn-4-ol (5)

To a solution of 1-hexyne (3), (1 g, 12.17 mmol) in THF (60 mL) at −78 °C under argon atmosphere was added nBuLi (1.6 M in hexanes, 14.6 mmol) dropwise. The reaction was allowed to reach −30 °C, and after 40 min, it was cooled again to −78 °C, and (E)-but-2-enal (1) (0.895 g, 12.78 mmol) was added dropwise. After 3h at −78 °C, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 60 mL of a cold saturated solution of NH4Cl and was extracted with 3 × 50 mL of EtOAc, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude extract was purified by flash chromatography (90:10, hexane: EtOAc), affording 5 (1.70 g, 92%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 5.86 (dq, J = 6.4, 15.8 Hz, 1H), 5.63 (dd, J = 6.2, 15.2 Hz, 1H), 4.79 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (t, J = 6.9 2H), 1.83 (bs, 1H), 1.72 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.54–1.33 (m, 4H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 130.6, 128.1, 86.5, 79.3, 62.9, 30.4, 21.7, 18.2, 17.2, 13.3.

Synthesis of rac-(E)-undec-4-en-7-yn-6-ol (6)

To a solution of 1-pentyne 4 (817 mg, 12 mmol) in THF (60 mL) at −78 °C was added nBuLi (1.6 M in hexanes, 13.2 mmol) dropwise. The reaction was allowed to reach −30 °C, and after 40 min, it was cooled again to −78 °C, and trans-2-hexenal (2) (1.41 g, 14.4 mmol) was added dropwise. After 3 h at −78 °C, the reaction was quenched by the addition of 60 mL of a cold saturated solution of NH4Cl and was extracted with 3 × 50 mL of EtOAc, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude extract was purified by flash chromatography (90:10, hexane: EtOAc), affording 6 (1.7 g, 92%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 0.11 (s, 6H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.45 (sext, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.57 (sext, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.06 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.34 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 4.84 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (dd, J = 6.2, 15.7 Hz, 1H), 5.88 (dt, J = 6.8, 15.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 13.5, 13.7, 20.8, 22.1, 34.0, 63.3, 79.8, 86.7, 129.7, 133.4; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C11H18O [M+] 166.1358, found 166.1357.

Synthesis of rac-(E)-tert-butyl(dec-2-en-5-yn-4-yloxy)dimethylsilane (7)

To a solution of alcohol 5 (2 g, 13.15 mmol) and imidazole (2.7 g, 39.5 mmol) in DCM (30 mL), TBSCl (2.21 g, 32.5 mmol) in 23 mL of DCM was added. The mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight and was quenched by the addition of water (50 mL) and extracted using DCM (3 × 50 mL). The organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude extract was purified by flash chromatography (99:1 hexane: EtOAc), affording 7 (3.25 g, 93%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 5.80 (dq, J = 6.5, 14.4 Hz, 1H), 5.56 (dd, J = 5.5, 15.1 Hz, 1H), 4.85 (d, J = 5.2 Hz), 2.24 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 1.72 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.55–1.40 (m, 4H), 0.93 (s, 12H), 0.92 (t, J = 4.0, 3H), 0.15 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 131.6, 126.1, 85.7, 80.3, 63.6, 30.7, 25.8, 21.9, 18.4, 18.3, 17.4, 13.5, −4.7.

Synthesis of rac-(E)-tert-butyldimethyl(undec-4-en-7-yn-6-yloxy)silane (8)

To a solution of alcohol 6 (1.8 g, 10.8 mmol) in DCM (50 mL), imidazole (2.21 g, 32.5 mmol) and TBSCl (2.21 g, 32.5 mmol) were added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction was quenched by the addition of water (25 mL) and was extracted using DCM (3 × 50 mL). The organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude extract was purified by flash chromatography (100% hexane), affording 8 (2.76 g, 90%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 0.13 (s, 3H), 0.14 (s, 3H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.92 (s, 9H), 0.98 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.42 (sext, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.54 (sext, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.20 (dt, J = 7.1, 2.0 Hz, 2H), 4.86 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 5.52 (ddt, J = 15.3, 5.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 5.77 (dtd, J = 15.3, 6.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ −4.7, −4.5, 13.4, 13.6, 18.3, 20.8, 22.0, 22.2, 25.8, 33.9, 63.8, 80.6, 85.4, 130.6, 131.1; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C17H32OSi [M+] 280.2222, found 280.2234.

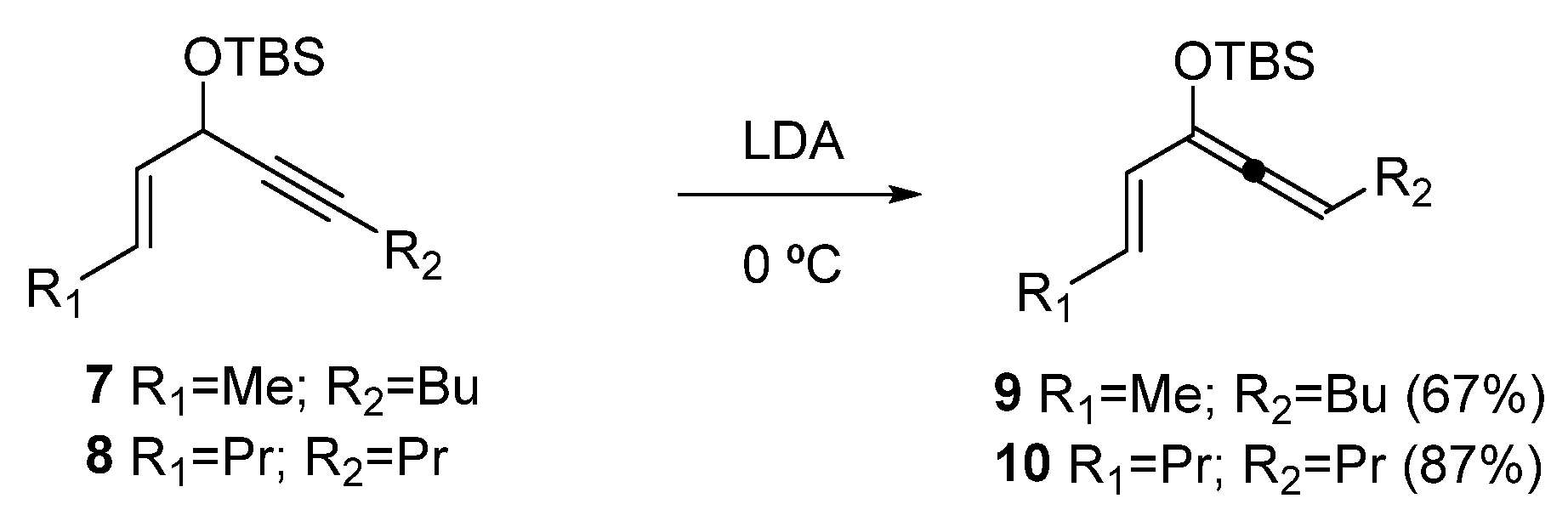

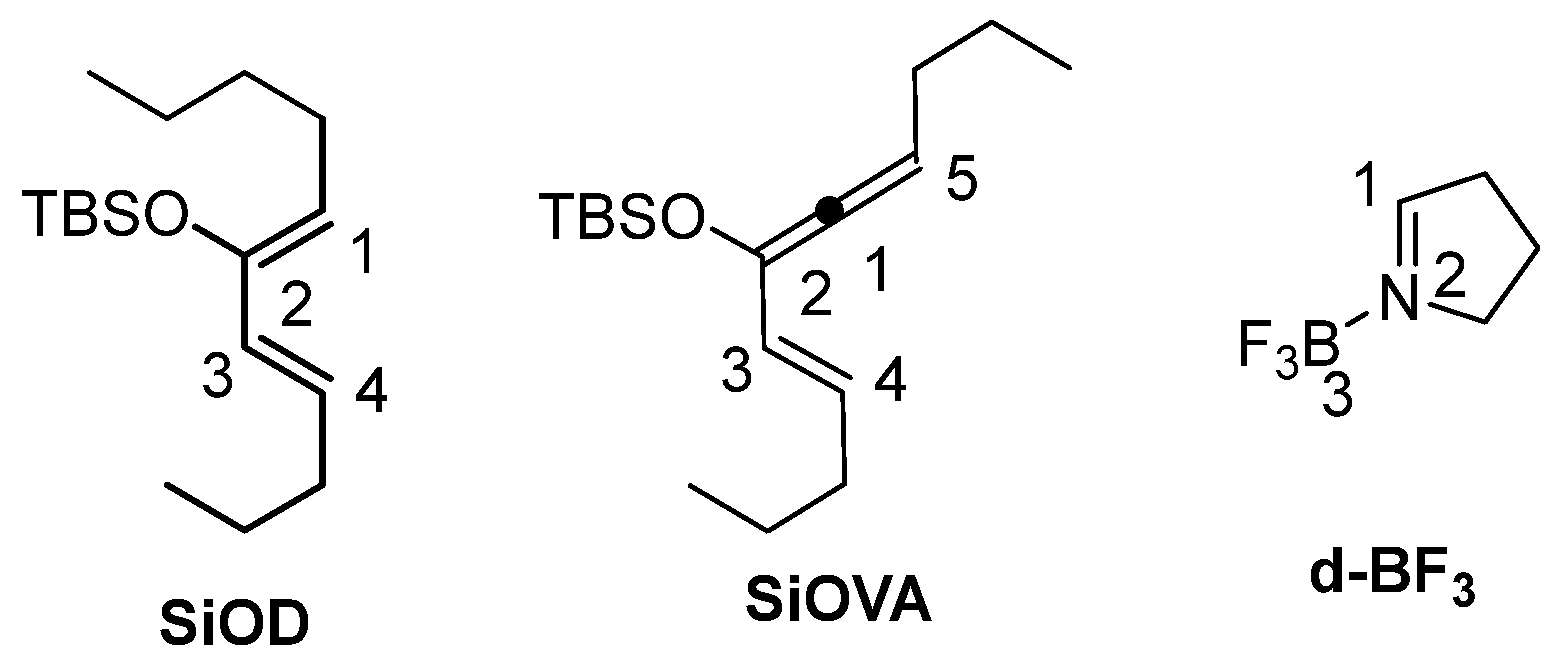

Synthesis of rac-(E)-tert-butyl(deca-2,4,5-trien-4-yloxy)dimethylsilane (9)

To a solution of 7 (200 mg, 0.75 mmol) in THF (4 mL) at 0 °C was added cold (−10 °C) LDA (1.58 mL, 0.5 M in THF, 0.79 mmol). After stirring for 20 min, an aqueous solution of NH4Cl (5 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was extracted with ethyl ether (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The oily residue obtained (134 mg, 0.50 mmol) resulted in almost pure 9 by NMR analysis (67%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 6.11 (dq, J = 6.6, 14.5 Hz, 1H), 5.94 (d, J = 15.2 Hz, 1H), 5.56 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 1.96–1.90 (m, 2H), 1.59 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H), 1.33–1.17 (m, 4H), 0.99 (s, 9H), 0.78 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.17 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 198.9, 127.6, 126.1, 124.1, 101.8, 30.9, 25.8, 22.3, 18.2, 17.6, 13.8, −4.6; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C16H30OSi [M+] 266.2066, found 266.2079.

Synthesis of rac-(E)-tert-butyldimethyl(undeca-4,5,7-trien-6-yloxy)silane (10)

To a solution of 8 (1 g, 3.6 mmol) in THF (36 mL) at −10 °C was added cold (−10 °C) LDA (0.5 M in THF, 3.93 mmol). After stirring for 30 min, imidazole (267 mg, 3.93 mmol) in THF (3 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was poured over hexane, and the solid was filtered out. The resulting solution was concentrated, and the oily residue obtained (870 mg) resulted in an almost pure 10 by NMR analysis (87% yield).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 0.23 (s, 3H), 0.24 (s, 3H), 0.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 0.86 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.06 (s, 9H), 1.29–1.44 (m, 4H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 2.04 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 5.61 (t, J = 6.6, 1H), 6.03 (d, J = 15.4 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (dt, J = 15.4, 7.2 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ −4.6, −4.4, 13.8, 13.9, 18.5, 22.3, 23.0, 26.0, 101.8, 126.2, 126.8, 129.8, 199.6; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C17H32OSi [M+] 280.2222, found 280.2229.

Synthesis of 4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)butanal (12)

To a solution of DMSO (0.84 mL, 11.76 mmol) in DCM (26 mL) at −60 °C under argon atmosphere, were added 2.94 mL of oxalyl chloride (2 M in DCM, 5.88 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 20 min, and then a solution of 11 (1.0 g, 4.9 mmol) in DCM (7 mL) was added. After stirring for 1 h at −60 °C, 3.4 mL of TEA (24.5 mmol) was added, and the reaction was allowed to reach room temperature. Then, water was added, and the reaction was extracted with DCM (3 × 50 mL). The organic phase was washed with 1% aqueous HCl (40 mL), water (40 mL), saturated solution of NaHCO3, brine (40 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. After purification using flash chromatography (90:10 hexane: EtOAc), 12 was obtained (0.7 g, 70%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) 9.66 (t, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H), 3.53 (d, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 2.38 (dt, J = 1.6, 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.74 (m, 2H), 0.76 (s, 9H), −0.07 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 202.5, 62.0, 40.7, 25.8, 25.5, 18.2, −5.5.

Synthesis of (E)-N-benzyl-4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)butan-1-imine (13).

To a mixture of 12 (0.5 g, 2.46 mmol) and MgSO4 (12 mg) in DCM (3 mL) at 0 °C, 0.27 mL of BnNH2 (0.263 g, 2.46 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C, then filtered and the solvent removed under reduced pressure, yielding imine 13 (0.717 g, 2.46 mmol, 100%).

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.45 (s, 1H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.44 Hz, 2H), 7.21 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.12–7.09 (m, 1H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 3.52 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H), 2.23 (bs, 2H), 1.75 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 0.97 (s, 9H), 0.03 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 164.1, 140.3, 128.3, 126.7, 65.1, 62.4, 32.3, 28.9, 25.9, 18.2, −5.3.

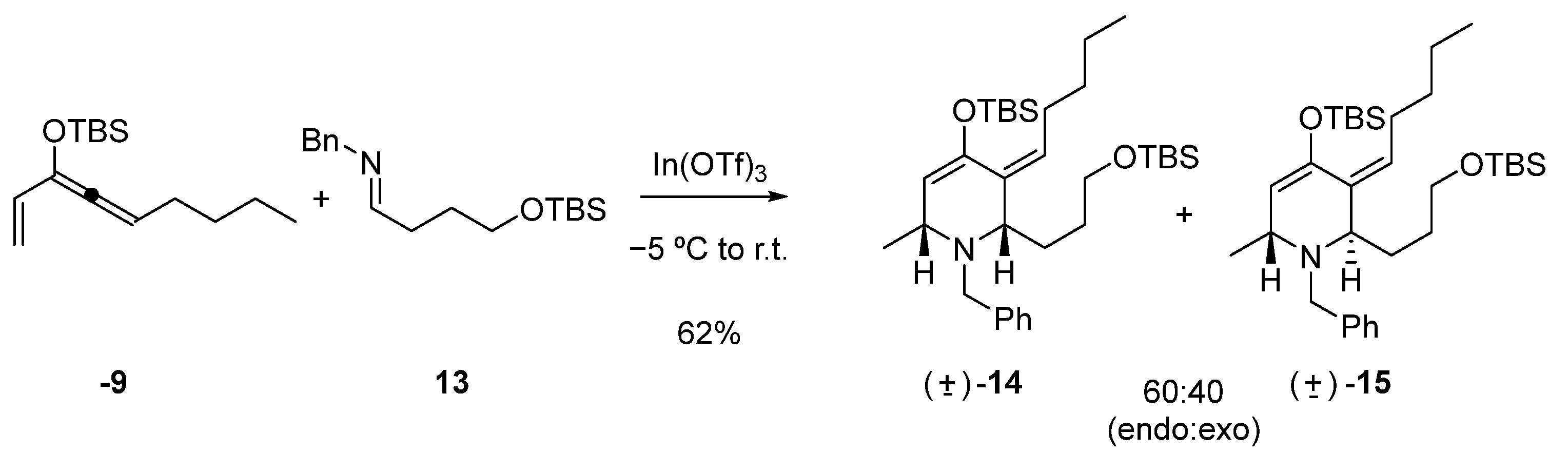

Hetero Diels–Alder reaction of 9 and 13 with In(OTf)3

To a solution of In(OTf)3 (328 mg, 0.58 mmol) in CH3CN (50 mL) at −5 °C, imine 13 (340 mg, 1.17 mmol) dissolved in CH3CN (5 mL) was added via cannula. The mixture was stirred for 5 min, then vinylallene 9 (310 mg, 1.17 mmol) dissolved in CH3CN (5 mL) was added via cannula. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight. A cold saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (40 mL) was added to stop the reaction. Extraction was performed with EtOAc (3 × 40 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with a saturated aqueous solution of NaCl, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The reaction product was purified by column chromatography (95:5, hexane: EtOAc). Compounds 14 (236 mg, 0.43 mmol) and 15 (158 mg, 0.29 mmol) were obtained in a 60:40 ratio and 62% yield.

rac-(2S,6R,Z)-1-benzyl-4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)propyl)-6-methyl-3-pentylidene-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (14)

Colorless oil. IR (νmax, cm−1): 2956, 2858, 1464, 1253, 1100; 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.47 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.10 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 4.82 (bs, 1H), 3.73 (d, J = 14 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 13.5 Hz, 1H), 3.61–3.55 (m, 2H), 3.26 (bs, 1H), 3.06 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.82–2.78 (m, 1H), 2.53–2.49 (m, 1H), 1.96–1.92 (m, 1H), 1.81–1.78 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.61 (m, 2H), 1.43 (bs, 4H), 1.22 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.04 (s, 9H), 0.99 (s, 9H), 0.96 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 0.22 (s, 6H), 0.07 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 145.9, 140.8, 130.2, 129.9, 128.8, 128.2, 126.9, 110.5, 67.2, 63.2, 61.6, 54.4, 32.9, 32.5, 30.8, 29.3, 27.1, 25.9, 23.3, 22.7, 18.3, 14.0, −4.1, −5.4.

rac-(2R,6R,Z)-1-benzyl-4-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-2-(3-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)propyl)-6-methyl-3-pentylidene-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (15)

Colorless oil. IR (νmax, cm−1): 3392, 2929, 2869, 1693, 1434, 1069; 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.48 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.24 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.11 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (s, 1H), 3.72 (d, J = 14 Hz, 1H), 3.60–3.57 (m, 3H), 3.54 (d, J = 14 Hz, 1H), 3.22 (bs, 1H), 2.71–2.59 (m, 2H), 1.88–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.67−1.62 (m, 3H), 1.36 (bs, 4H), 1.12 (d, J = 7 Hz, 3H), 1.03 (s, 9H), 1.00 (s, 9H), 0.98–0.92 (m, 3H), 0.21 (s, 6H), 0.07 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 147.8, 141.2, 131.3, 129.2, 128.6, 128.2, 126.7, 111.1, 63.1, 51.4, 50.5, 32.8, 30.2, 29.2, 26.0, 25.1, 22.7, 20.1, 18.3, 14.1.

Synthesis of rac-(2S,6R,Z)-1-benzyl-2-(3-hydroxypropyl)-6-methyl-3-pentylidenepiperidin-4-one (16)

A small portion of TBAF was added to a solution of the cycloadduct 14 (150 mg, 0.26 mmol) in THF (5 mL) at 0 °C. After 12 h of stirring and after all the starting material had been consumed, cold water (10 mL) was added. Extraction was carried out with ethyl ether (4 × 10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with a saturated NaCl solution (10 mL) and dried with Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the reaction product was purified by column chromatography (60:40, hexane: EtOAc), yielding compound 16 (68 mg, 0.21 mmol, 80%).

1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 7.31 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.11 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 5.49 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.61 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.27–3.20 (m, 2H), 3.10 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 2.70–2.61 (m, 3H), 2.36–2.24 (m, 2H), 1.55–1.48 (m, 1H), 1.42–1.24 (m, 8H), 0.93 (d, J = 3.0 Hz, 3H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 200.2, 141.1, 140.1, 135.8, 129.2, 128.2, 127.1, 66.1, 62.1, 58.0, 53.4, 46.6, 35.1, 31.9, 29.8, 28.7, 22.5, 21.9, 13.9; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C21H31NO2 [M+] 329.2355, found 329.2354.

Synthesis of rac-3-((2S,6R,Z)-1-benzyl-6-methyl-4-oxo-3-pentylidenepiperidin-2-yl)propanal (17)

To a DMSO solution (33 mg, 0.03 mL, 0.426 mmol) in DCM (3 mL) at −60 °C under an argon atmosphere, 0.09 mL of Cl2(CO)2 (2 M in DCM, 0.18 mmol) was added. The mixture was stirred for 20 min at the same temperature. Then, a solution of 16 (50 mg, 0.15 mmol) in DCM (1 mL) was added via cannula. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at −60 °C, and then 0.10 mL of TEA (75.8 mg, 0.75 mmol) was added, and the reaction was allowed to reach room temperature. After 4 h of stirring, water was added, and the mixture was extracted with DCM (3 × 10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with 1% HCl (aq) solution (10 mL), water (10 mL), saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (10 mL), and saturated aqueous NaCl solution (10 mL), then dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated. The resulting crude was purified by column chromatography (80:20, hexane: EtOAc), yielding aldehyde 17 (30 mg, 0.092 mmol, 62%).

1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 9.12 (s, 1H), 7.21–7.09 (m, 5H), 5.46 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 3.51 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (d, J = 14.0 Hz, 1H), 3.00 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.69–2.54 (m, 3H), 2.24–2.22 (m, 2H), 1.61–1.62 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.23 (m, 7H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H), 0.86 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 199.7, 167.0, 142.1, 139.9, 135.1, 129.3, 127.4, 127.1, 64.8, 58.1, 53.2, 46.5, 40.4, 31.8, 30.9, 28.7, 22.5, 21.8, 13.9.

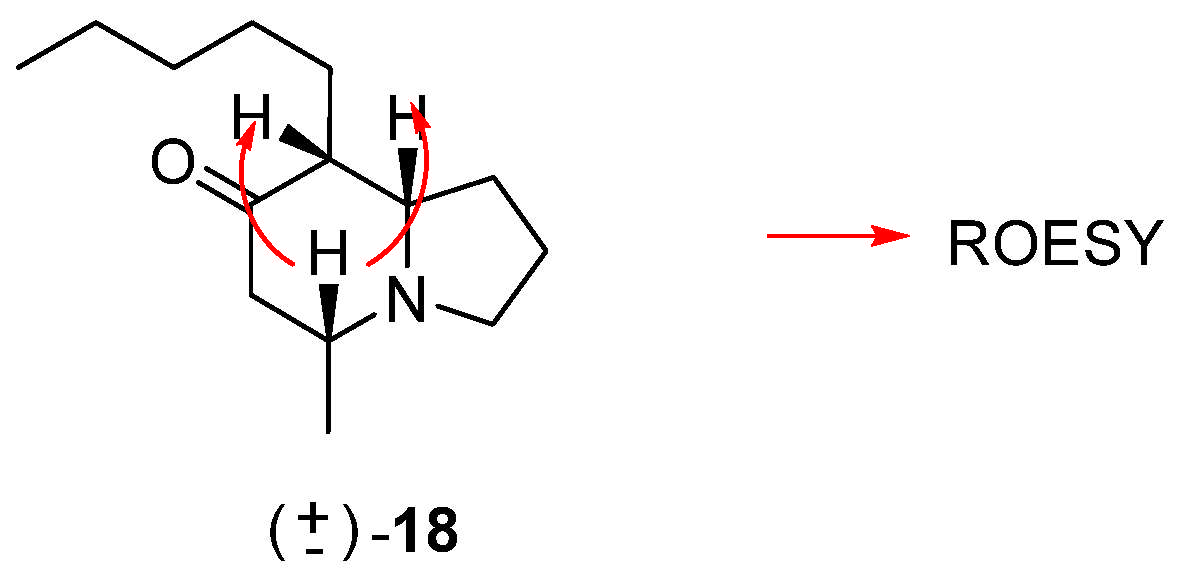

Synthesis of rac-(5R,8aS)-5-methyl-8-pentylhexahydroindolizin-7(1H)-one (18)

To a solution of 17 (30 mg, 0.092 mmol) in MeOH (2 mL), at room temperature, 10% Pd/C (3 mg) was added and placed in a Parr hydrogenator at 3 atm. After 12 h of reaction, it was filtered, and the solvent was removed under vacuum, obtaining 18 (14 mg, 0.042 mmol, 46%).

1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 2.91 (dt, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.14 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.11–2.00 (m, 3H), 1.81–1.72 (m, 2H), 1.67–1.55 (m, 3H), 1.50–1.45 (m, 1H), 1.35–1.16 (m, 8H), 0.84 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.80 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 208.0, 68.8, 57.1, 55.8, 50.6, 49.2, 32.5, 30.3, 27.7, 26.0, 22.7, 21.5, 21.2, 14.1; HRMS (FAB+): Calcd for C14H25NO [M+] 223.1936, found 223.1929.

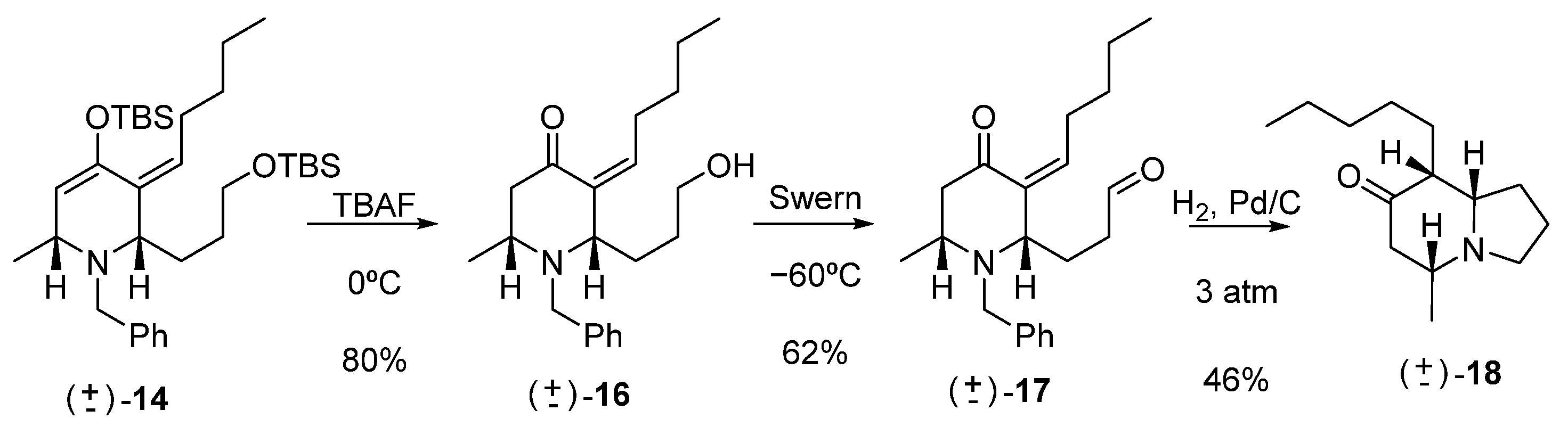

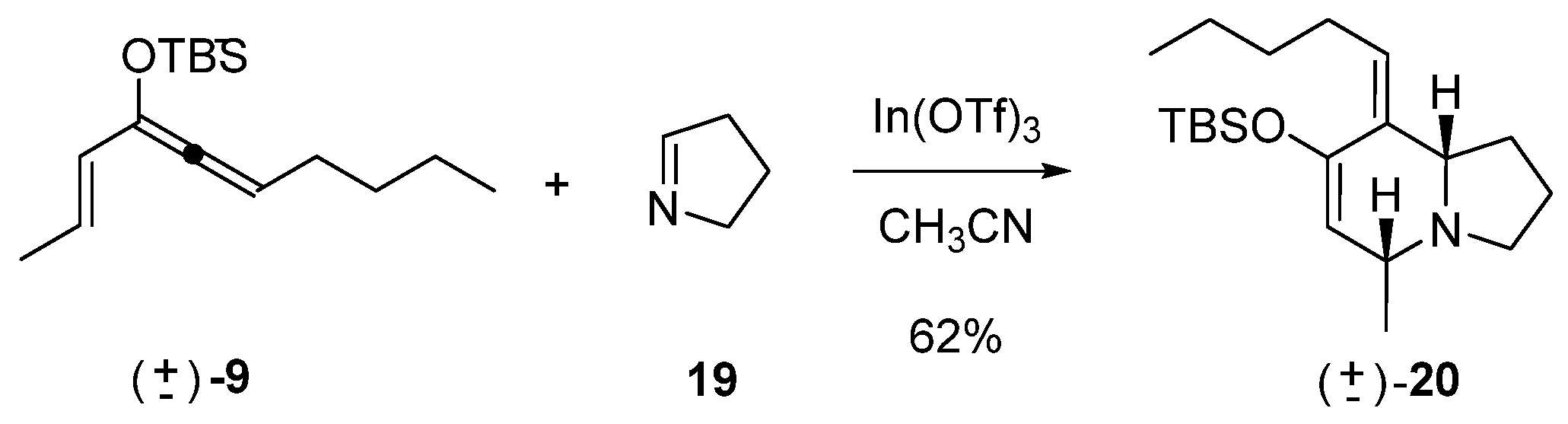

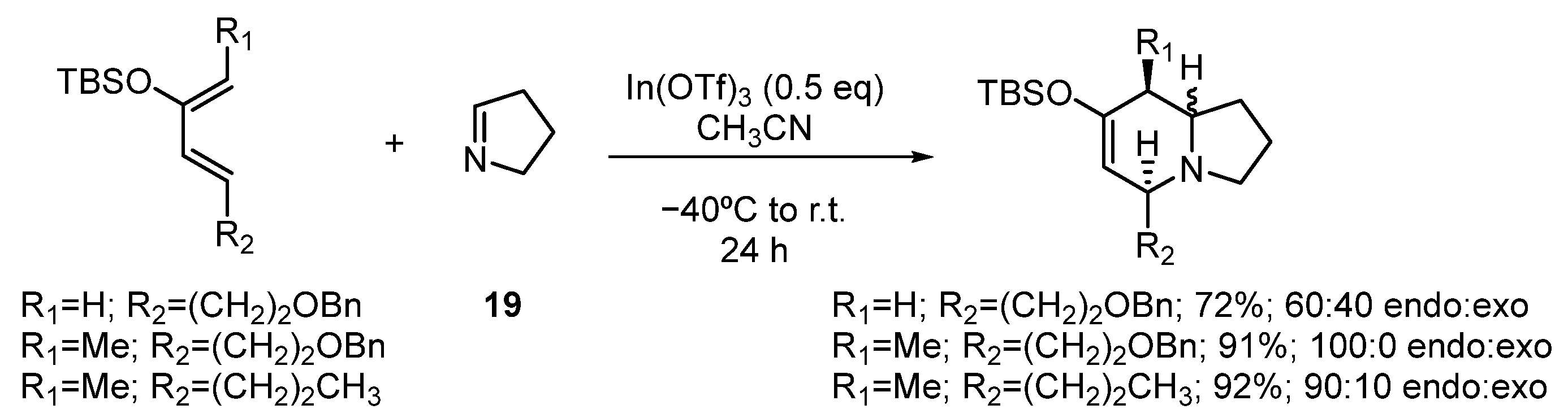

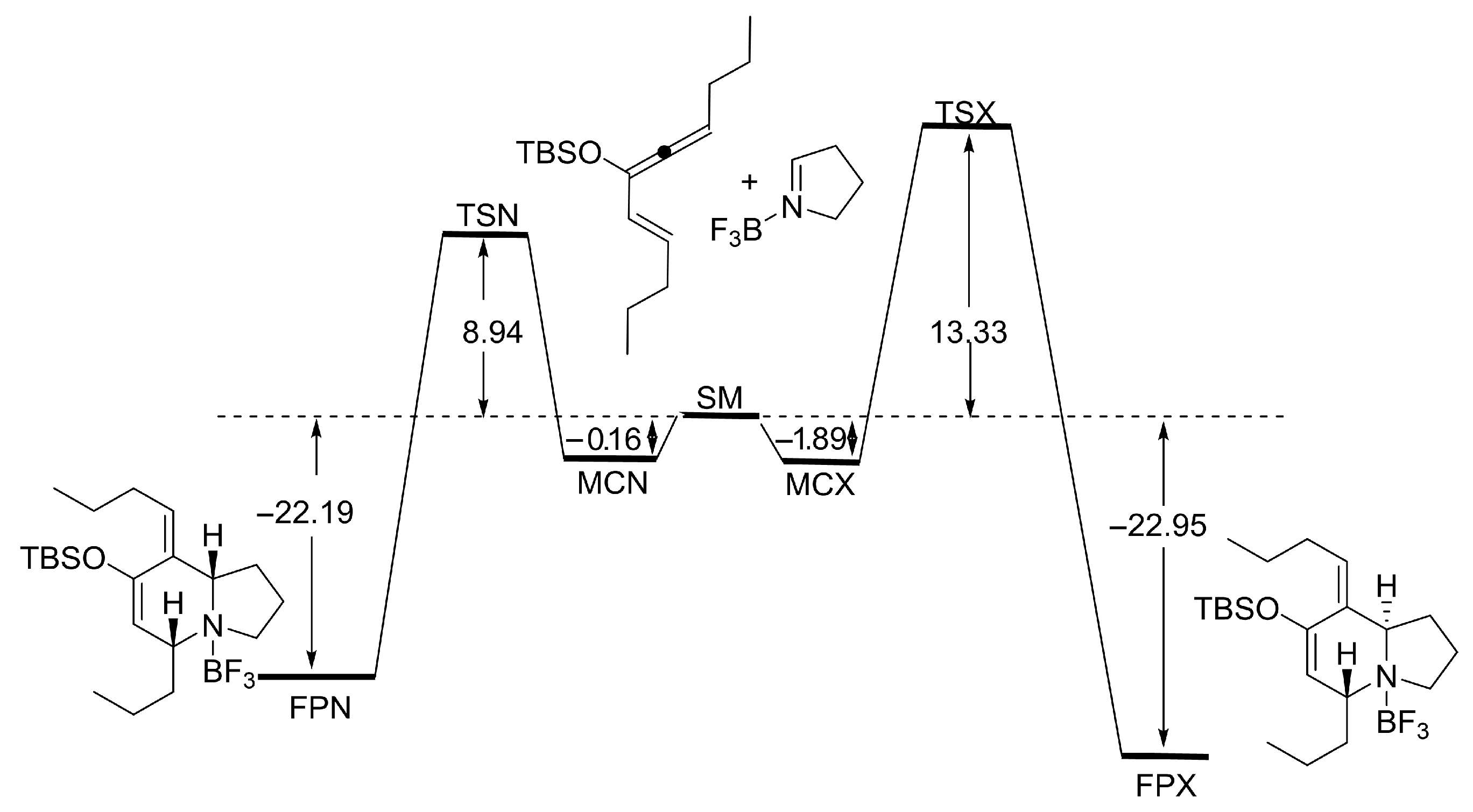

Hetero Diels–Alder reaction of 9 and Δ1-pyrroline (19)

To a solution of In(OTf)3 (210 mg, 0.38 mmol) in CH3CN (25 mL) at −5 °C, a solution of 19 (52 mg, 0.75 mmol) in CH3CN (2 mL) was added via cannula. The mixture was stirred for 5 min, then a solution of 9 (200 mg, 0.75 mmol) in CH3CN (2 mL) was added via cannula. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight. A cold, saturated aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (30 mL) was added to stop the reaction. The reaction was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with a saturated aqueous solution of NaCl, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated. The reaction product was purified by column chromatography (80:20, hexane: EtOAc), yielding 156 mg of 20 (0.47 mmol, 62%).

rac-(5R,8aS,Z)-7-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-5-methyl-8-pentylidene-1,2,3,5,8,8a-hexahydroindolizine (20)

IR (νmax, cm−1): 2959, 2859, 2780, 1611, 1463, 1254; 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 5.29 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 4.89 (s, 1H), 3.24 (dt, J = 2.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.89–2.85 (m, 2H), 2.78–2.72 (m, 1H), 2.67–2.63 (m, 1H), 1.94 (q, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 1.82 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 1.78–1.73 (m, 1H), 1.61–1.55 (m, 1H), 1.44–1.27 (m, 5H), 1.16 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 1.02 (s, 9H), 0.92 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H), 0.21 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 149.4, 133.9, 126.5, 113.8, 65.9, 57.3, 52.6, 33.0, 29.1, 28.9, 26.2, 22.8, 21.7, 21.3, 18.6, 14.1, −4.0.

Synthesis of (5R,8aS,Z)-5-methyl-8-pentylidenehexahydroindolizin-7(1H)-one (21)

A small portion of TBAF was added to a solution of 20 (70 mg, 0.20 mmol) in THF (2 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction was monitored by TLC. After 12 h of stirring and complete consumption of the starting material, cold water (10 mL) was added. Extraction was carried out with ethyl ether (4 × 10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with a saturated NaCl solution (10 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the reaction product was purified by column chromatography (20:80, hexane: EtOAc), yielding 37 mg of 21 (0.17 mmol, 85%).

IR (νmax, cm−1): 2961, 2873, 2787, 1716, 1375, 1187; 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 5.58 (dt, J = 1.5, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (dt, J = 1.5, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 2.69–2.66 (m, 2H), 2.59 (bs, 1H), 2.39 (dd, J = 3.5, 16.0 Hz, 1H), 2.25–2.15 (m, 3H), 1.76–1.59 (m, 4H), 1.48–1.31 (m, 4H), 0.87 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.84 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 199.3, 138.2, 137.9, 67.4, 55.6, 51.2, 49.7, 31.9, 28.9, 28.8, 22.5, 21.4, 21.1, 13.9; HRMS (FAB+): Calcd for C14H23NO [M+] 221.1780, found 221.1768.

Hydrogenation of 21

To a solution of 21 (42 mg, 0.19 mmol) in MeOH (4 mL), 10% Pd/C (6 mg, 0.02 mmol) was added, and the mixture was placed in a hydrogen atmosphere at 1 atm pressure. After 12 h of reaction, the reaction mixture was filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The crude reaction mixture was purified by column chromatography (40:60, hexane: EtOAc), yielding 18 (23.3 mg, 0.11 mmol, 55%) and 8.4 mg of the isomerization compound 22 (0.04 mmol, 20%).

rac-(R)-5-methyl-8-pentyl-2,3,5,6-tetrahydroindolizin-7(1H)-one (22)

1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 2.92–2.83 (m, 1H), 2.77–2.72 (m, 1H), 2.47–2.32 (m, 3H), 2.23–2.03 (m, 4H), 1.65–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.43–1.40 (m, 4H), 1.30–1.22 (m, 2H), 0.96 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H), 0.71 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 189.0, 163.6, 163.3, 52.3, 50.0, 44.2, 32.1, 30.0, 29.9, 25.9, 23.0, 20.9, 17.5, 14.2.

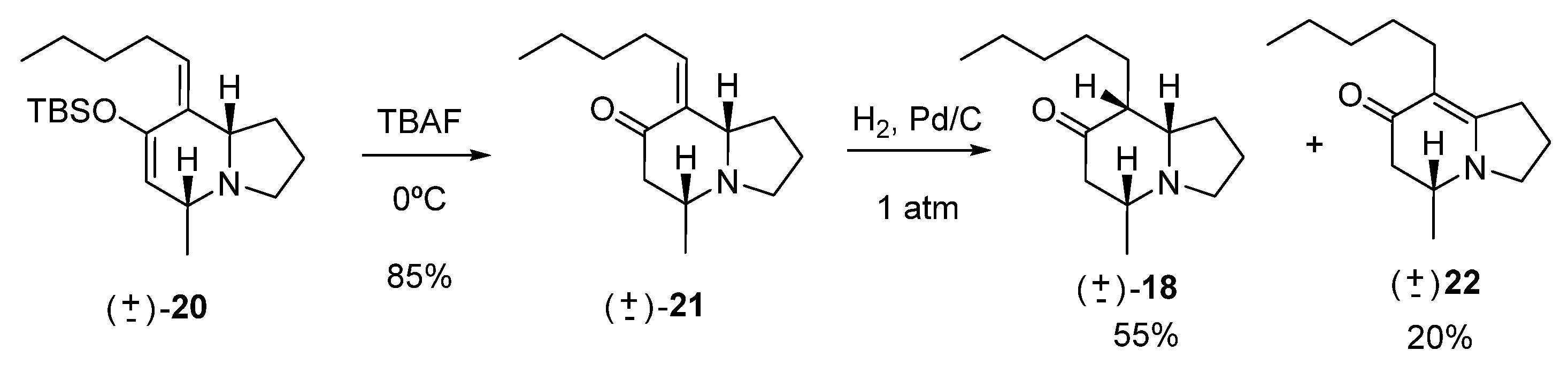

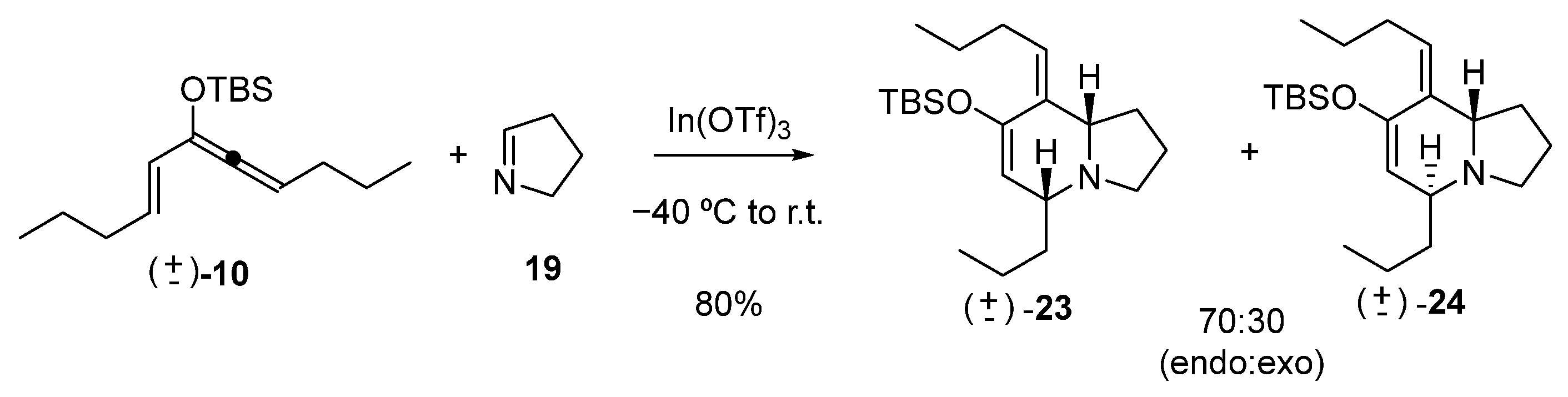

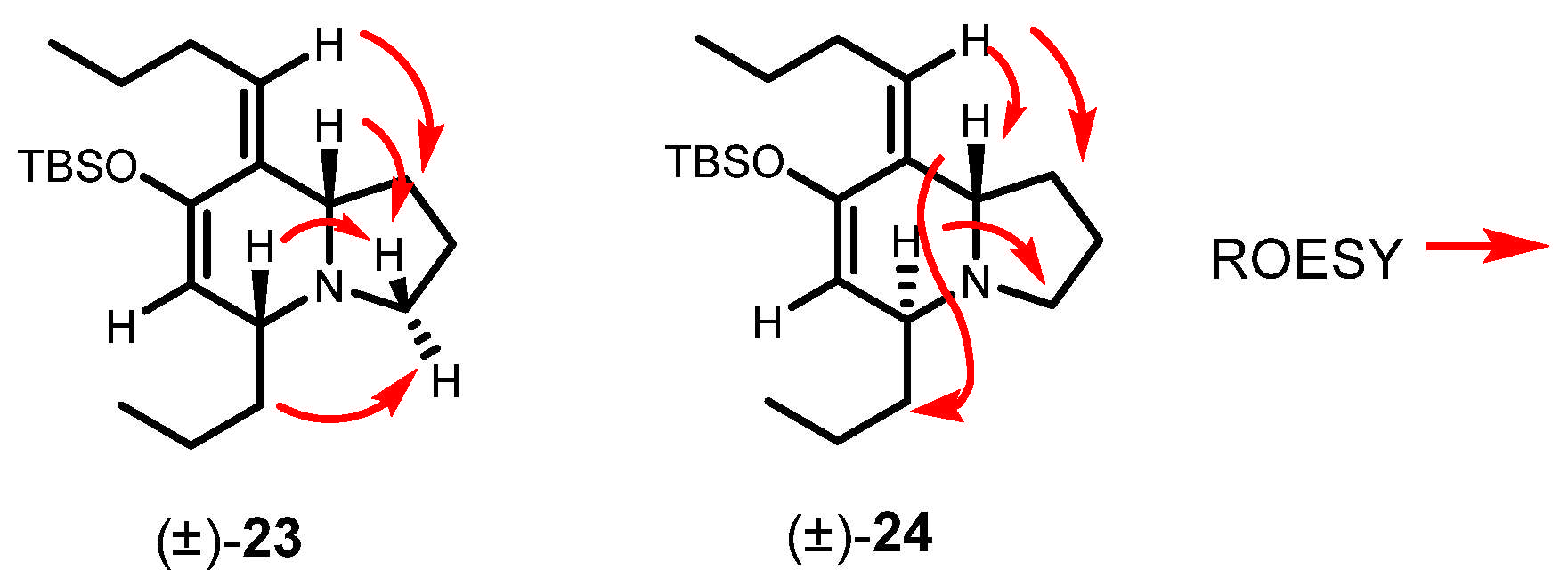

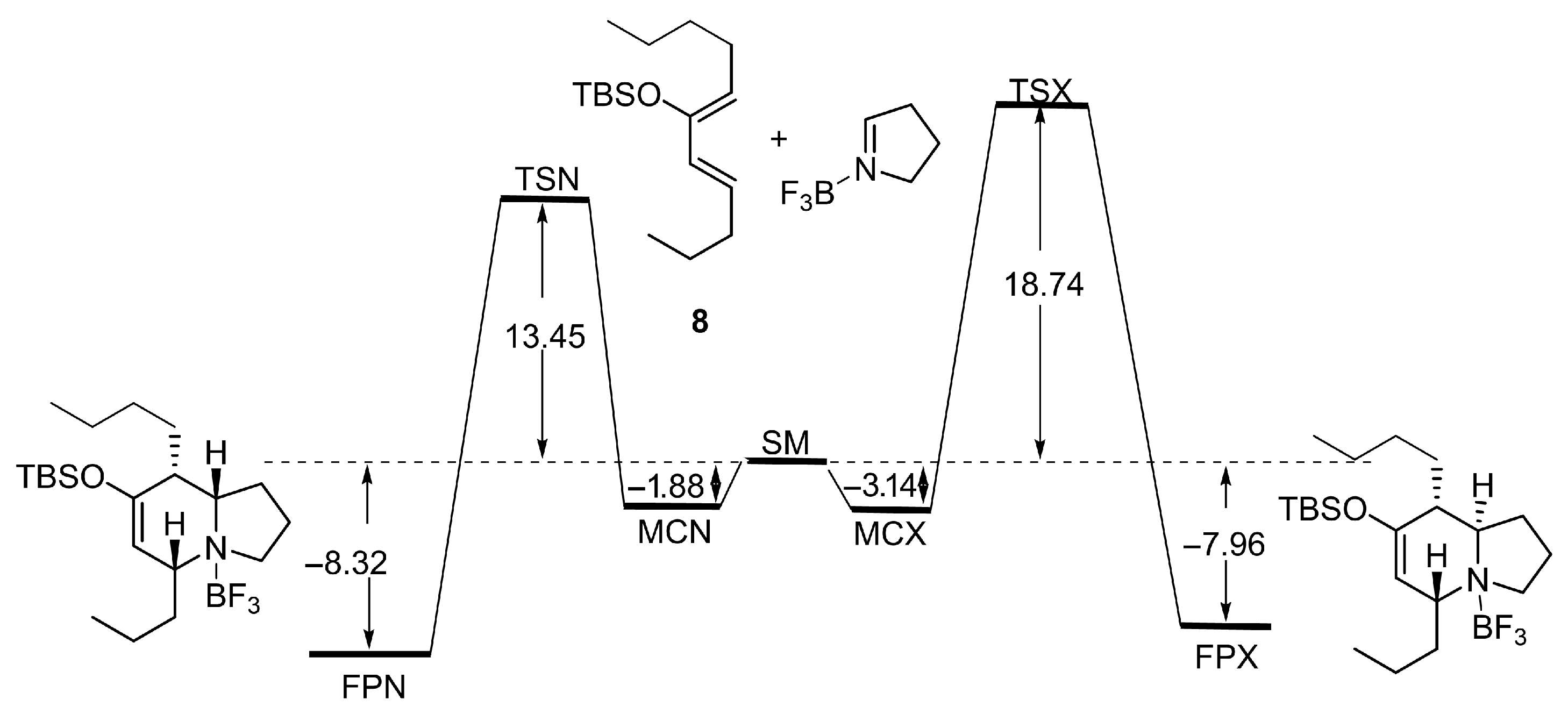

Hetero Diels–Alder reaction of 10 and Δ1-pyrroline (19)

To a solution of In(OTf)3 (871 mg, 1.55 mmol) in dry CH3CN (15 mL) at 0 °C was added a solution of freshly distilled Δ1-pyrroline (19) (257 mg, 3.72 mmol) in CH3CN (3 mL) at 0 °C under argon. After 15 min, the mixture was cooled at −40 °C, and a solution of siloxy vinylallene 10 (869 mg, 3.10 mmol) in CH3CN (5 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was allowed to slowly warm up to room temperature and was stirred for 24 h, quenched with NaHCO3 aqueous solution, extracted with EtOAc, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by flash chromatography to give the corresponding products, 23 and 24 (870 mg, 80%) in a 70:30 ratio.

rac-(5R,8aS,Z)-7-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-8-butylidene-5-propyl-1,2,3,5,8,8a-hexahydroindolizine (23)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 0.10 (s, 6H), 0.78 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H), 0.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (s, 9H), 1.49–1.14 (m, 5H), 1.73–1.55 (m. 3H), 1.82 (q, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (m, 1H), 2.75 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (bs, 1H), 3.10 (td, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 4.94 (s, 1H), 5.16 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ −3.8, −3.7, 14.2, 14.8, 18.2, 18.8, 22.0, 24.1, 26.4, 29.1, 31.7, 37.2, 52.6, 62.1, 66.2, 112.1, 126.2, 134.4, 150.2; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C21H39NOSi [M+] 349.2801, found 349.2794.

rac-(5R,8aR,Z)-7-((tert-butyldimethylsilyl)oxy)-8-butylidene-5-propyl-1,2,3,5,8,8a-hexahydroindolizine (24)

Colorless oil. 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 0.32 (s, 3H), 0.34 (s, 3H). 1.05 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H), 1.08 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.14 (s, 9H), 1.14–1.49 (m, 4H), 1.95 (m, 2H), 2.00 (m, 2H), 2.77 (q, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (m, 2H), 3.35 (m, 1H), 3.87 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 5.39 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ −4.0, −3.9, 14.1, 14.6, 18.7, 20.2, 22.6, 24.0, 26.3, 31.3, 31.9, 37.2, 51.6, 55.8, 60.8, 111.4, 127.31, 132.1, 148.2; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C21H39NOSi [M+] 349.2801, found 349.2794.

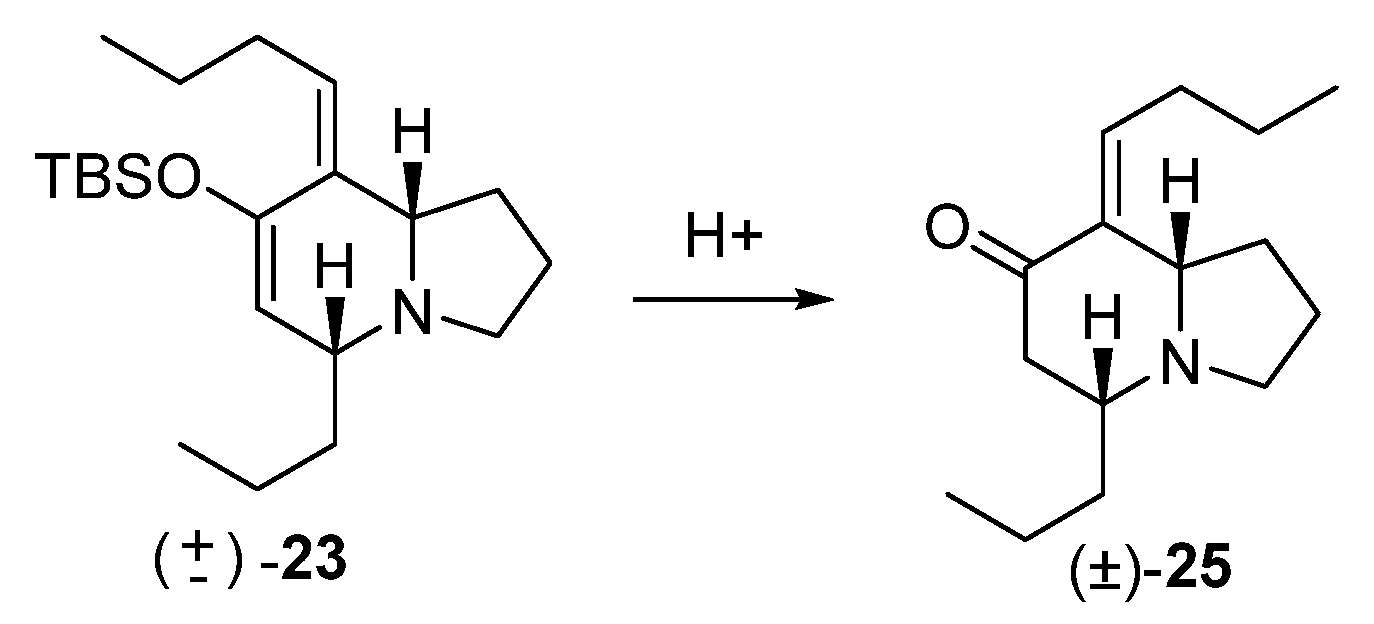

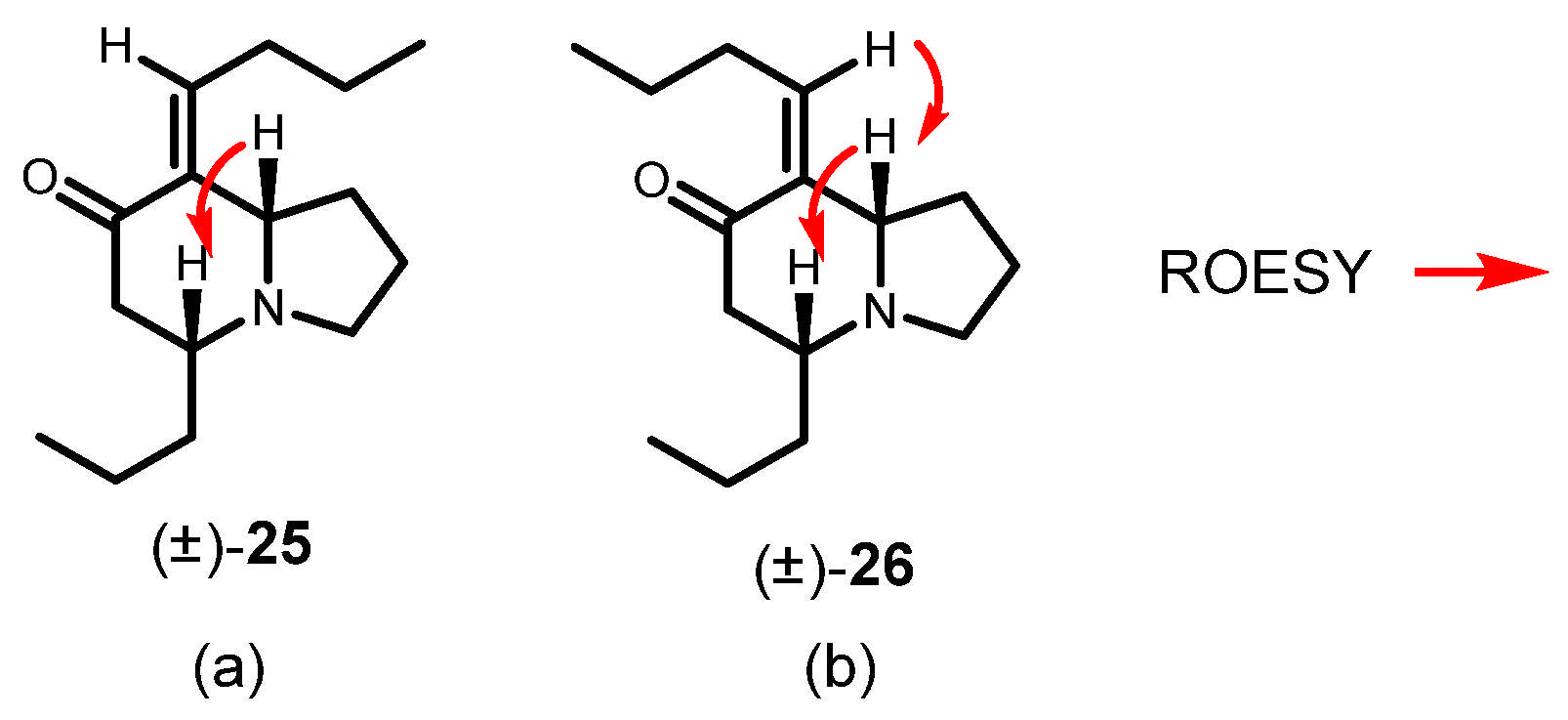

HCl treatment of 23

To a solution of 23 (850 mg, 2.4 mmol) in THF (10 mL) were added 4 mL of 10% aq HCl. The reaction was stirred at rt for 3 h. Then a saturated solution of NaHCO3 was added, and the reaction was extracted with ether (3 × 50 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude extract was purified by flash chromatography (35:65, hexane: EtOAc), yielding 263 mg of (5R*,8aS*, E)-8-butylidene-5-propylhexahydroindolizin-7(1H)-one (25) (46% yield).

Colorless oil, 1H NMR (C6D6, 500 MHz) δ 0.77 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.79 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.13, (m, 3H), 1.24 (sext, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.39 (m, 3H), 1.45–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.85 (dq, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 1.98 (m, 2H), 2.03 (quint, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.31 (m, 2H), 2.51 (m, 1H), 2.75 (dt, J = 7.8, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 3.28 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dt, J = 7.6, 2.5 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (C6D6, 125 MHz) δ 14.0, 14.4, 18.7, 22.4, 22.8, 30.9, 31.8, 37.3, 42.8, 47.5, 56.3, 63.5, 139.0, 140.0, 197.8; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C15H25NO [M+] 235.1936, found 235.1936.

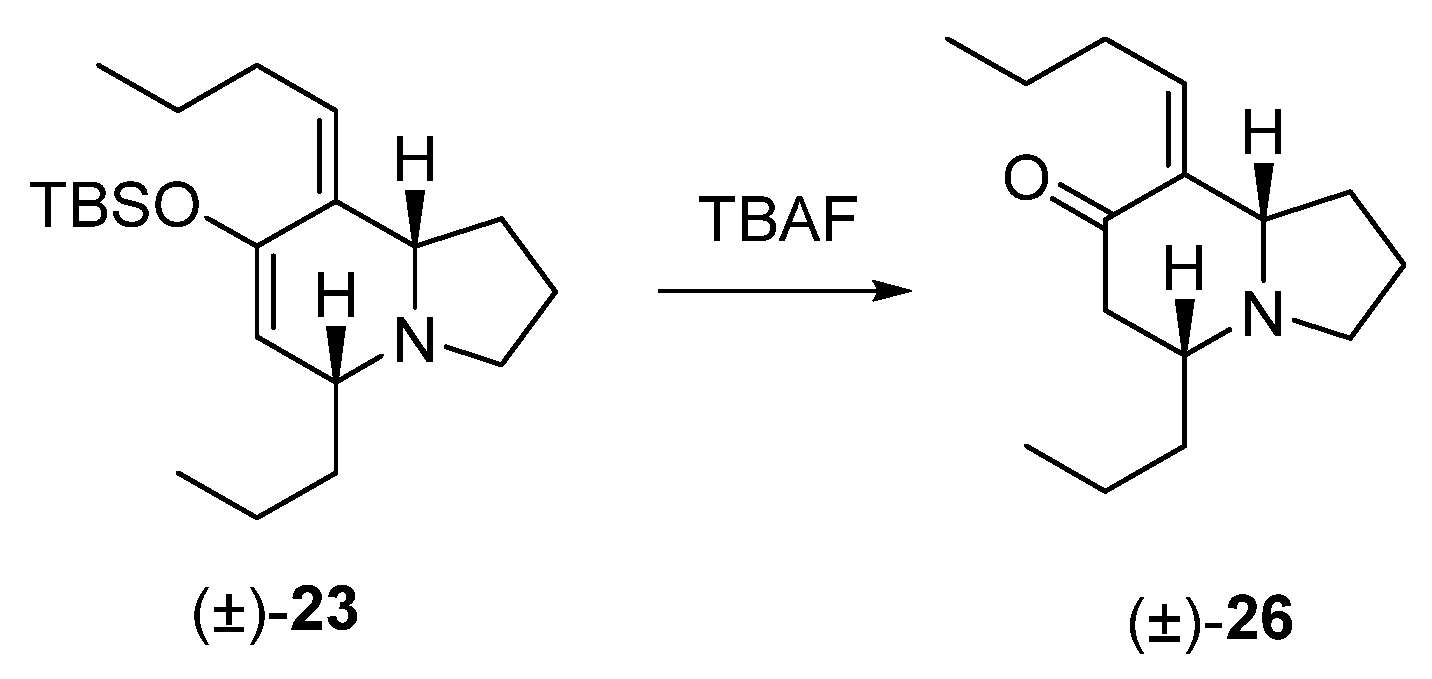

TBAF treatment of 23

To a solution of 23 (70 mg, 0.2 mmol) in THF (5 mL) was added a small amount of TBAF. The reaction was stirred at rt for 15 min and was quenched by adding water (5 mL), and was extracted with ethyl ether (3 × 20 mL). The extract was washed with brine, dried with Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude was purified by flash chromatography (35:65, hexane: EtOAc), yielding 42 mg of (5R*,8aS*, Z)-8-butylidene-5-propylhexahydroindolizin-7(1H)-one (26) (90%).

Colorless oil, 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz) δ 0.88 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.23 (m, 1H), 1.38 (m, 4H), 1.63 (m, 1H), 1.74 (m, 1H), 1.85 (m, 2H), 2.02 (m, 1H), 2.16 (m, 1H), 2.27 (dd, J = 16.7, 16.2 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.45 (m, 1H), 2.54 (dd, J = 16.7, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (m, 1H), 3.28 (dt, J = 8.8, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 5.72 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 13.8, 14.2, 18.2, 21.3, 22.7, 28.6, 31.2, 37.1, 46.6, 51.2, 60.1, 67.4, 137.3, 139.4, 200.9; HRMS (EI+): Calcd for C15H25NO [M+] 235.1936, found 235.1947.