Synergistic Zn/Al Co-Doping and Sodium Enrichment Enable Reversible Phase Transitions in High-Performance Layered Sodium Cathodes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

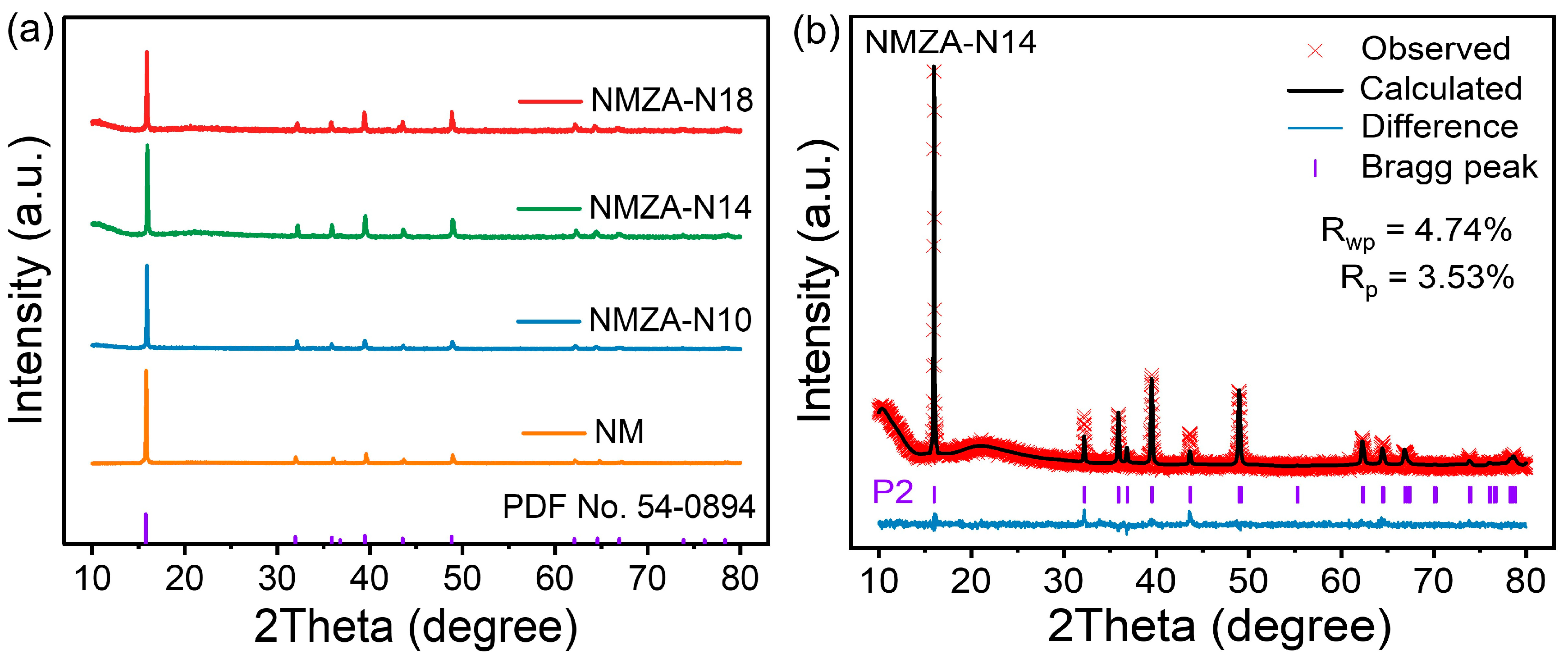

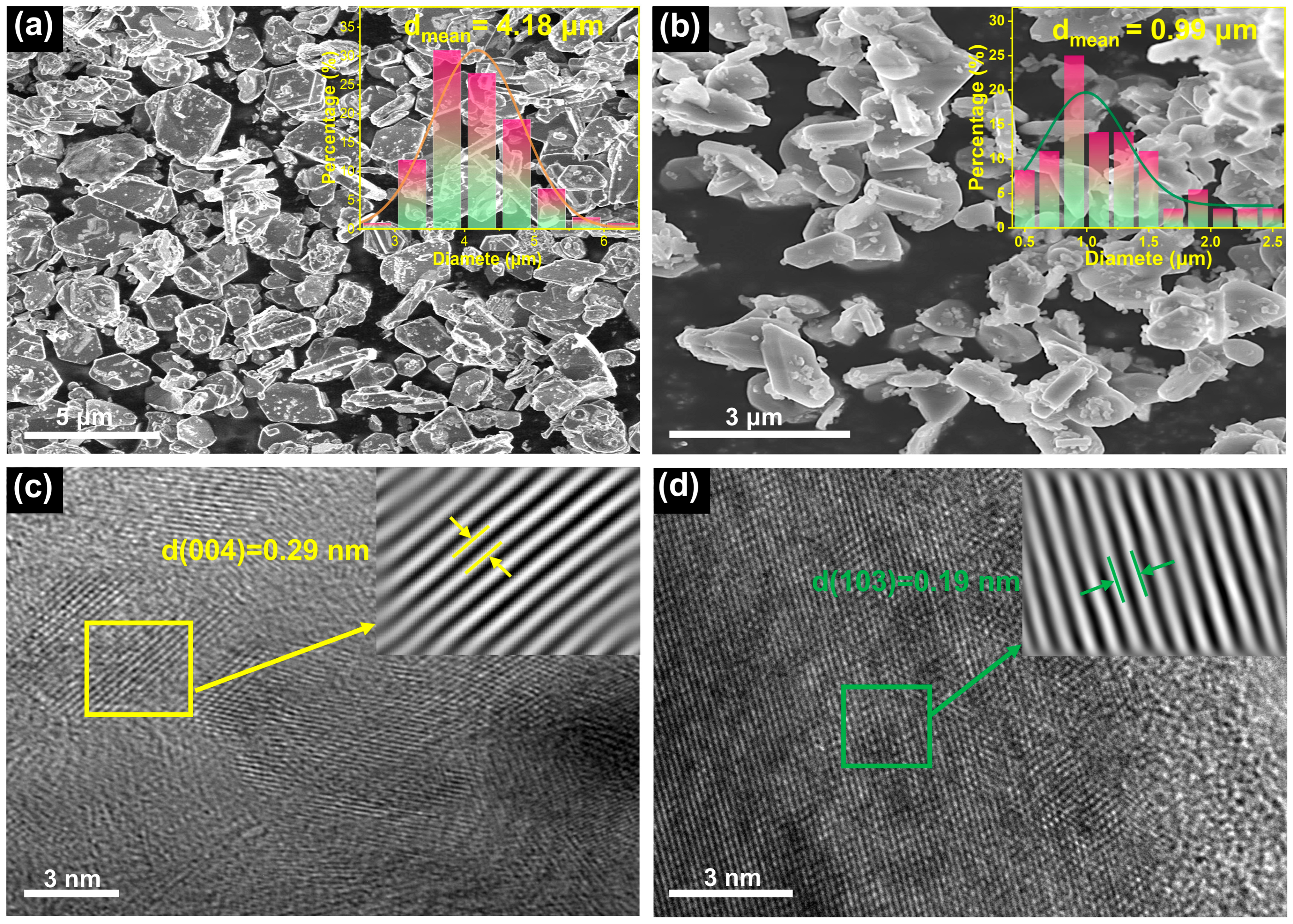

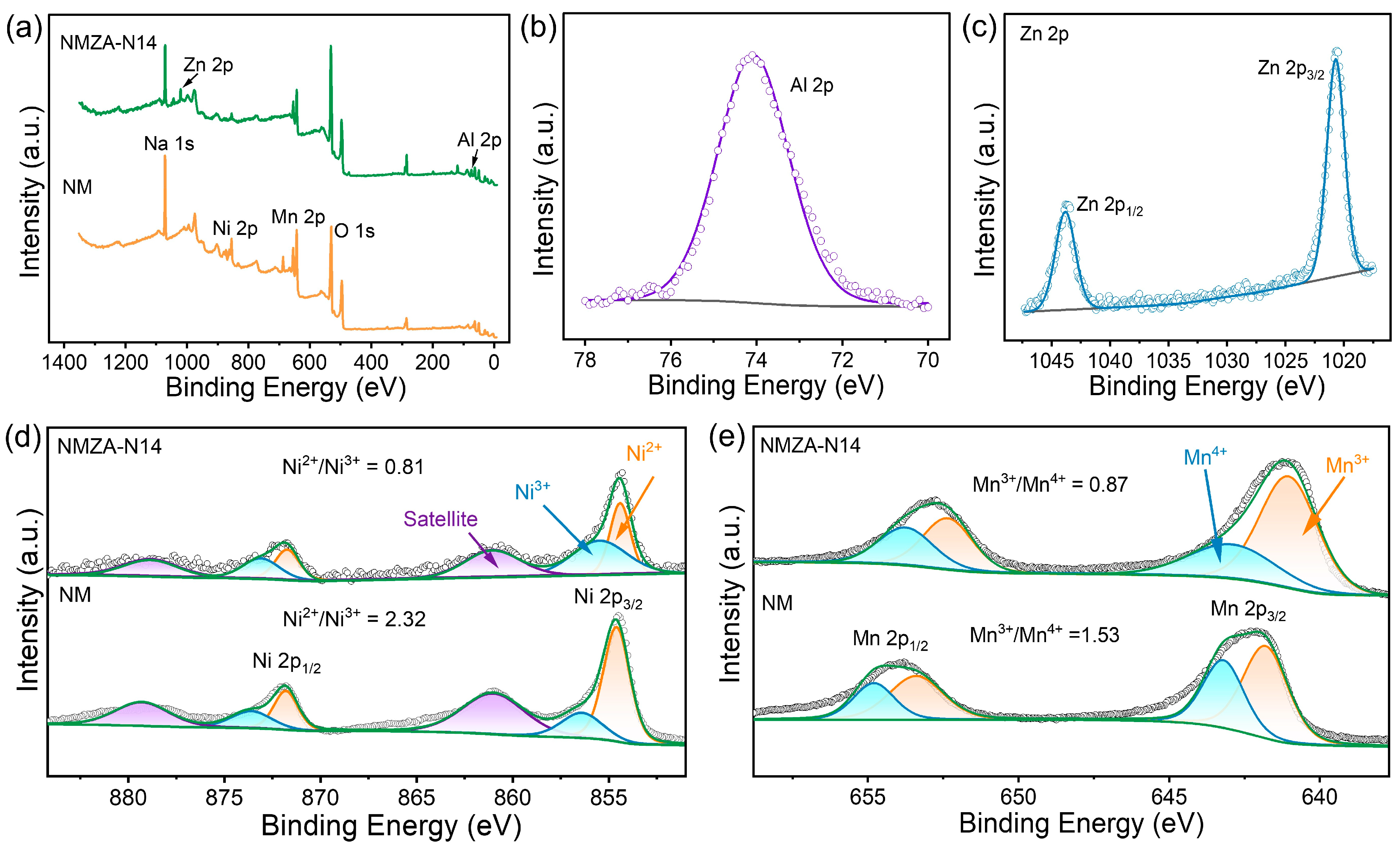

2.1. Crystal Structures

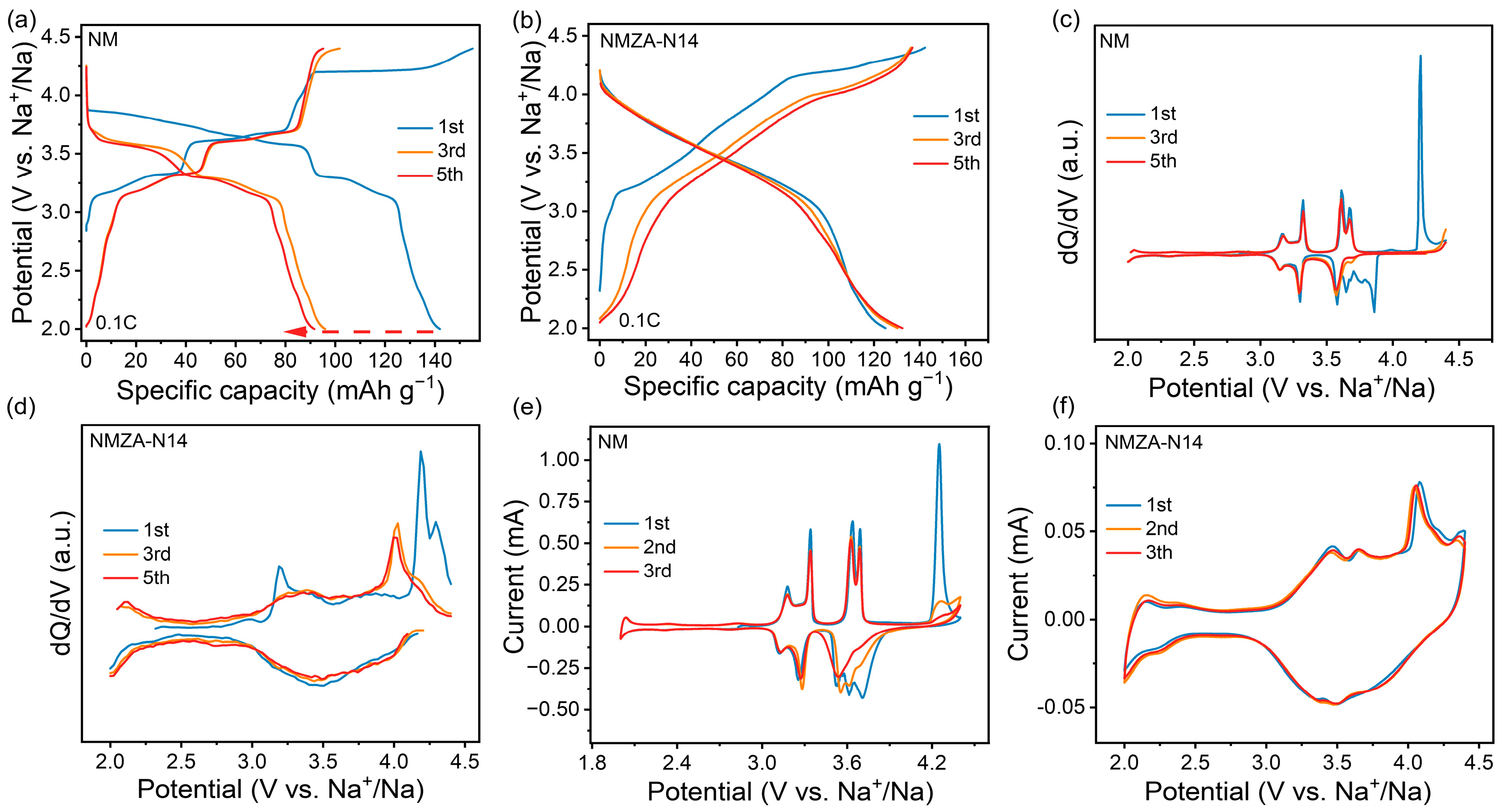

2.2. Electrochemical Performance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of Materials

3.2. Material Characterization

3.3. Electrochemical Measurements

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, Y.; Zhu, B.X.; Xia, Z.Z.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.J.; Xin, Y.; Zhao, Q.S.; Wu, M.B. Oxygen-vacancy engineered SnO2 dots on rGO with N-doped carbon nanofibers encapsulation for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Molecules 2025, 30, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Q.X.; Li, Z.Y.; Ruan, H.L.; Luo, D.W.; Wang, J.J.; Ding, Z.Y.; Chen, L.N. A review of carbon anode materials for sodium-ion batteries: Key materials, sodium-storage mechanisms, applications, and large-scale design principles. Molecules 2024, 29, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, L.F.; Cheng, Z.Y.; Liu, L.Y.; Wang, Y.S.; Du, T. Recent advances on F-doped layered transition metal oxides for sodium ion batteries. Molecules 2023, 28, 8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, M.J.; Sun, H.Z. Review on modification strategy of layered transition metal oxide for sodium. ion battery cathode material. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.H.; Song, X.S.; Sun, H.H.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.C.; Sun, Y.K. High-energy and long-life O3-type layered cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.H.; Cui, M.; Gong, Y.P.; Guo, Z.W.; Le, S.Q.; Wu, Y.J.H.; Lin, C.; Li, K.; Tian, J.Y.; Qi, Y. Synthesis of F-doped high-entropy layered oxide as cathode material towards high-performance Na-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2025, 61, 4371–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Y.X.; Wu, Y.X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Sun, H.P. Interface issues of layered transition metal oxide cathodes for sodium-ion batteries: Current status, recent advances, strategies, and prospects. Molecules 2024, 29, 5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzadi, K.; Zhao, X.H.; Liu, Q.; He, W.X.; Mu, D.B.; Li, Y.Q.; Li, L.; Chen, R.J.; Wu, F. Advancing sodium-ion battery performance: Innovative doping and coating strategies for layered oxide cathode materials. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2025, 9, 2401045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, S.H.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, X.; Mu, W.N.; Teng, F. Cu-doped layered P2-type Na0.67Ni0.33-xCuxMn0.67O2 cathode electrode material with enhanced electrochemical performance for sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 404, 126578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaqat, A.; Suntharam, N.M.; Sadaqat, A.; Bashir, S.; Ali, G. Recent progress and technical challenges in the development of potential layered transition metal oxide cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 150, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.C.; Li, L.Y.; Ma, Z.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Luo, Z.G. Co-operative interaction of multiple ions for P2-type sodium-ion battery cathodes at high-voltage cyclability. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, H.Y.; Yang, C.S.; Lui, Z.J.; Lin, Z.H.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, S.S.; Li, S.K.; Zhang, S.Q. Promoting threshold voltage of P2-Na0.67Ni0.33Mn0.67O2 with Cu2+ cation doping toward high-stability cathode for sodium-ion battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 659, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, M.M.; Ma, J.W.; Wei, G.F.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, R.Y.; Huang, Y.H. Revisiting the. Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 cathode: Oxygen redox chemistry and oxygen release suppression. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-Ruiz, N.; Dose, W.M.; Sharma, N.; Chen, H.R.; Heath, J.; Somerville, J.W.; Maitra, U.; Islam, M.S.; Bruce, P.G. High voltage structural evolution and enhanced Na-ion diffusion in P2-Na2/3Ni1/3-xMgxMn2/3O2 (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.2) cathodes from diffraction, electrochemical and ab initio studies. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1470–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.C.; Lin, G.L.; Liu, P.; Sun, Z.Q.; Si, Y.C.; Wang, Q.L.; Jiao, L.F. Synergetic enhancement of structural stability and kinetics of P′2-type layered cathode for sodium-ion batteries via cation-anion co-doping. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 67, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.H.; Li, J.Y.; Fan, Y.X.; Liu, Y.K.; Zhang, P.; Shi, X.Y.; Ma, J.W.; Zhang, R.Y.; Huang, Y.H. Suppressed P2-P2′ phase transition of Fe/Mn-based layered oxide cathode for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wang, L.G.; Zhu, H.; Chu, J.; Fang, Y.J.; Wu, L.N.; Huang, L.; Ren, Y.; Sun, C.J.; Liu, Q.; et al. Ultralow-strain Zn-substituted layered oxide cathode with suppressed P2-O2 transition for stable sodium ion storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.H.; Ni, Y.X.; Tan, S.; Hu, E.Y.; He, L.H.; Liu, J.D.; Hou, M.C.; Jiao, P.X.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, F.Y. Realizing high capacity and zero strain in layered oxide cathodes via lithium dual-site substitution for sodium-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9596–9606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.S.; Zuo, W.H.; Zheng, B.Z.; Xiang, Y.X.; Zhou, K.; Xiao, Z.M.; Shan, P.Z.; Shi, J.W.; Li, Q.; Zhong, G.M.; et al. P2-Na0.67AlxMn1-xO2: Cost-effective, stable and high-rate sodium electrodes by suppressing phase transitions and enhancing sodium cation mobility. Angew Chem. Int. Edit. 2019, 58, 18086–18095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.H.; Xu, G.L.; Zhong, G.M.; Gong, Z.L.; McDonald, M.J.; Zheng, S.Y.; Fu, R.Q.; Chen, Z.H.; Amine, K.; Yang, Y. Insights into the effects of zinc doping on structural phase transition of P2-type sodium nickel manganese oxide cathodes for high-energy sodium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 22227–22237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.L.; Yao, Z.P.; Wang, Q.D.; Li, H.F.; Wang, J.L.; Liu, M.; Ganapathy, S.; Lu, Y.X.; Cabana, J.; Li, B.H.; et al. Revealing high Na-content P2-type layered oxides for advanced sodium-ion cathodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5742–5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Jing, P.P.; Zhao, C.Y.; Guan, Z.K.; Guo, N.; Liu, J.L.; Shi, Y.L.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, M.T. Charge compensation modulation and crystal growth optimization synergistically boosting a P2-type layered cathode of sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 160147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.C.; Meng, J.K.; Yue, X.Y.; Qiu, Q.Q.; Song, Y.; Wu, X.J.; Fu, Z.W.; Xia, Y.Y.; Shadike, Z.; Wu, J.P.; et al. Tuning P2-structured cathode material by Na-site Mg substitution for Na-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.H.; Fang, X.; Zhang, A.Y.; Shen, C.F.; Liu, Q.Z.; Enaya, H.A.; Zhou, C.W. Layered P2-Na2/3[Ni1/3Mn2/3]O2 as high-voltage cathode for sodium-ion batteries: The capacity decay mechanism and Al2O3 surface modification. Nano Energy 2016, 27, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.B.; Peng, C.; Wu, J.; Yang, T.T.; Zeng, J.; Li, F.K.; Kucernak, A.; Xue, D.F.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, M.; et al. Regulating electron distribution of P2-type layered oxide cathodes for practical sodium-ion batteries. Mater. Today 2023, 68, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.F.; Yao, H.R.; Liu, X.Y.; Yin, Y.X.; Zhang, J.N.; Wen, Y.R.; Yu, X.Q.; Gu, L.; Guo, Y.G. Na+/vacancy disordering promises high-rate Na-ion batteries. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaar6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, Z.X.; Chen, D.L.; Lu, B.; Zhang, Q.H.; Hou, Y.; Wu, Z.G.; Ye, Z.Z.; Li, T.T.; Lu, J.G. Structural regulation of P2-type layered oxide with anion/cation codoping strategy for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 35, 2418322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.H.; Zeng, C.H.; Zhang, H.Z.; Shi, X.; Yu, Y.X.; Lu, X.H. Valence engineering enhancing NH4+ storage capacity of manganese oxides. Small 2023, 19, 2206727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, Q.C.; Zhu, K.J.; Deng, T.; Zhang, J.X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.Q.; Jiao, L.F.; Wang, C.S. Realizing complete solid-solution reaction in high sodium content P2-type cathode for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Angew Chem. Int. Edit. 2020, 59, 14511–14516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.X.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, S.L.; Tian, R.Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, H.Z.; Liu, S.Q.; Shi, X.X.; Zhang, N.; Song, D.W.; et al. Dual-site pinning engineering in O3-type layered oxides cathode materials for high-performance sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 513, 162805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Q.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Gao, J.Q.; Yin, S.Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Fang, S.S.; Yu, M.; Xiao, X.H.; et al. Reversible OP4 phase in P2-Na2/3Ni1/3Mn2/3O2 sodium ion cathode. J. Power Sources 2021, 508, 230324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.S.; Li, S.; Gao, A.; Zheng, J.Y.; Zhang, Q.H.; Lu, X.; Gu, L.; Cao, D.P. Probing the structural transition kinetics and charge compensation of the P2-Na0.78Al0.05Ni0.33Mn0.60O2 cathode for sodium ion batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 24122–24131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.T.; Li, J.R.; Obrovac, M.N. Crystal structures and electrochemical performance of air-stable Na2/3Ni1/3-xCuxMn2/3O2 in sodium cells. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.J.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.T.; Sun, C.C.; Lin, C.F.; Zhang, T.; Chu, W.S.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Tao, S. Introducing high-valence element into P2-type layered cathode material for high-rate sodium-ion batteries. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.W.; Yoon, G.H.; Koo, C.; Lee, S.H.; Koo, S.; Kwon, D.; Song, S.H.; Jeon, T.Y.; Baik, H.; et al. Rigid-spring-network in P2-type binary Na layered oxides for stable oxygen redox. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 53, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, Y.; Yang, T.; Chen, N.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Miao, Y.; Shi, C.; Ma, J.; Qin, X. Synergistic Zn/Al Co-Doping and Sodium Enrichment Enable Reversible Phase Transitions in High-Performance Layered Sodium Cathodes. Molecules 2025, 30, 4628. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234628

Qin Y, Yang T, Chen N, Li J, Li A, Miao Y, Shi C, Ma J, Qin X. Synergistic Zn/Al Co-Doping and Sodium Enrichment Enable Reversible Phase Transitions in High-Performance Layered Sodium Cathodes. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4628. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234628

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Yaru, Tingfei Yang, Na Chen, Jiale Li, Anqi Li, Yu Miao, Chenglong Shi, Jianmin Ma, and Xue Qin. 2025. "Synergistic Zn/Al Co-Doping and Sodium Enrichment Enable Reversible Phase Transitions in High-Performance Layered Sodium Cathodes" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4628. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234628

APA StyleQin, Y., Yang, T., Chen, N., Li, J., Li, A., Miao, Y., Shi, C., Ma, J., & Qin, X. (2025). Synergistic Zn/Al Co-Doping and Sodium Enrichment Enable Reversible Phase Transitions in High-Performance Layered Sodium Cathodes. Molecules, 30(23), 4628. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234628