Influence of Extrusion Cooking Parameters on Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of Potato-Based Snack Pellets Enriched with Cricket Powder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

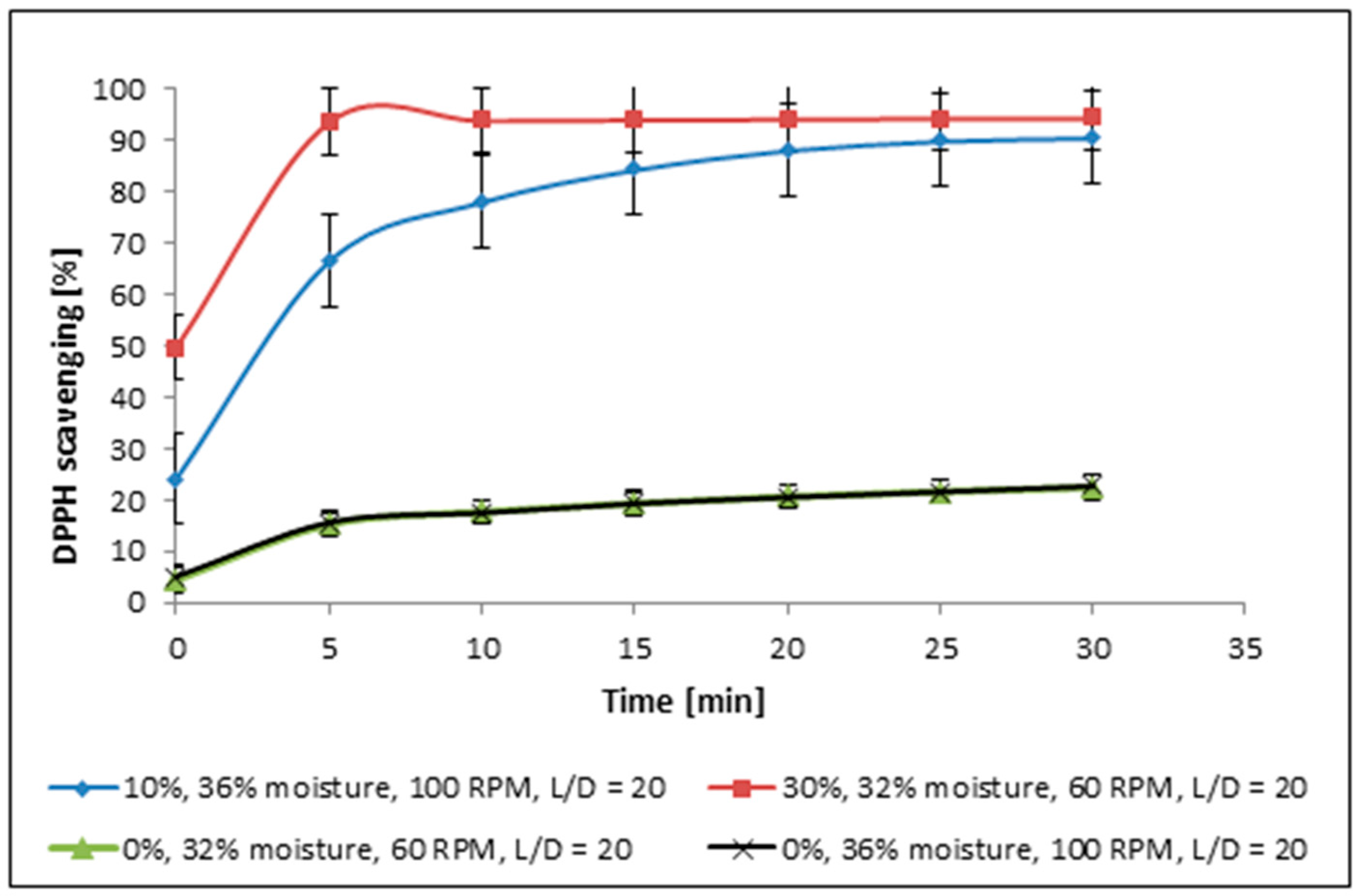

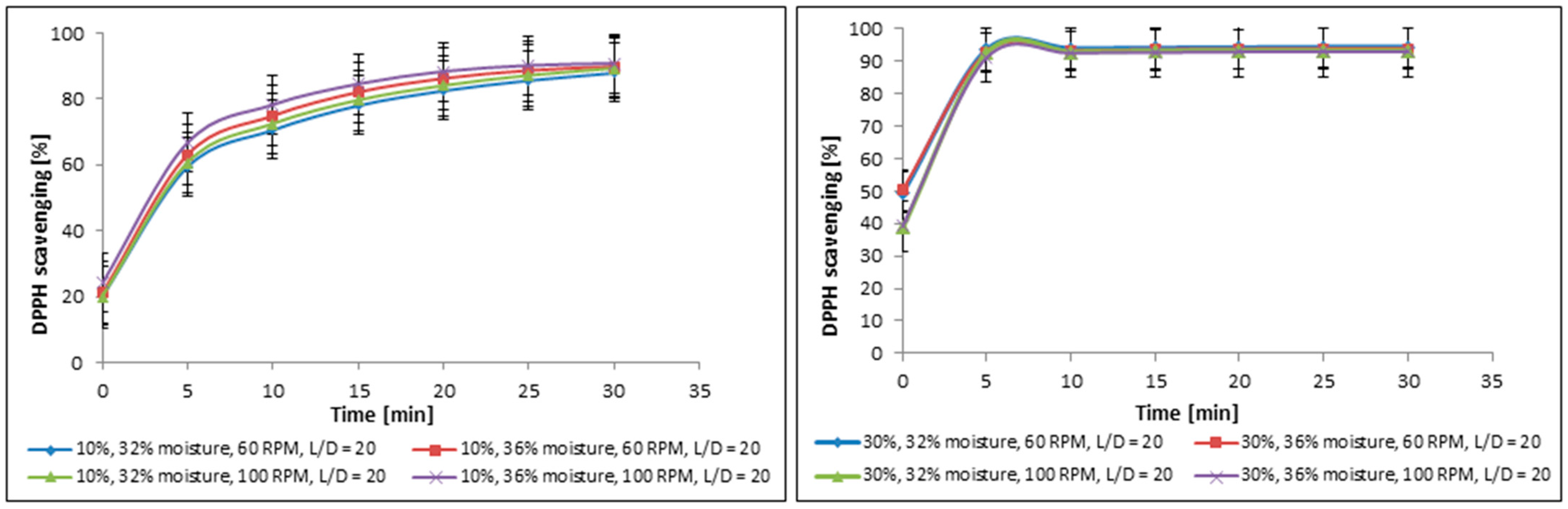

2.1. Free Radical Scavenging Activity—DPPH Method

2.2. Total Content of Polyphenolic Compounds (TPCs) and Chromatographic Analysis of Free Phenolic Acids

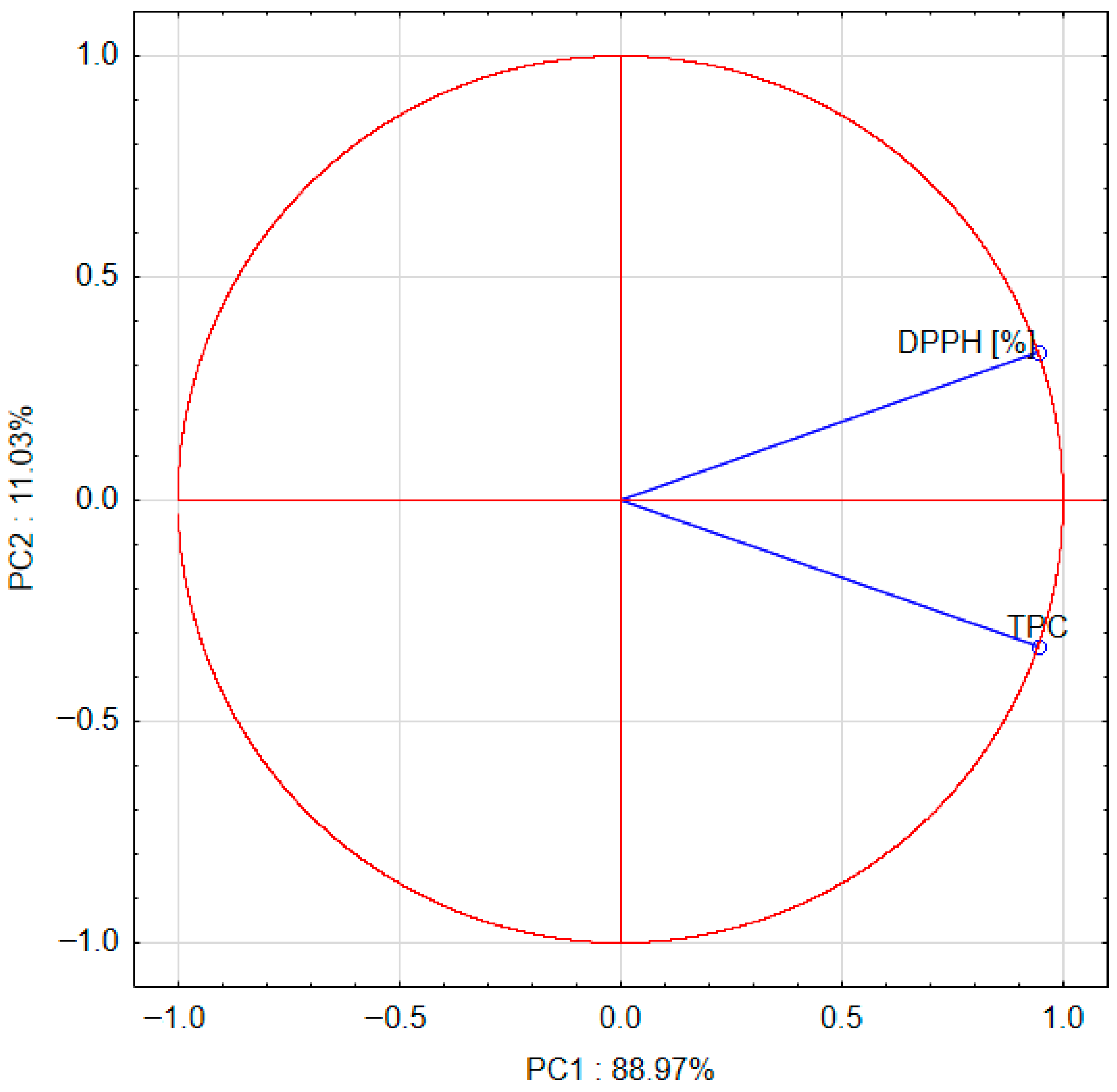

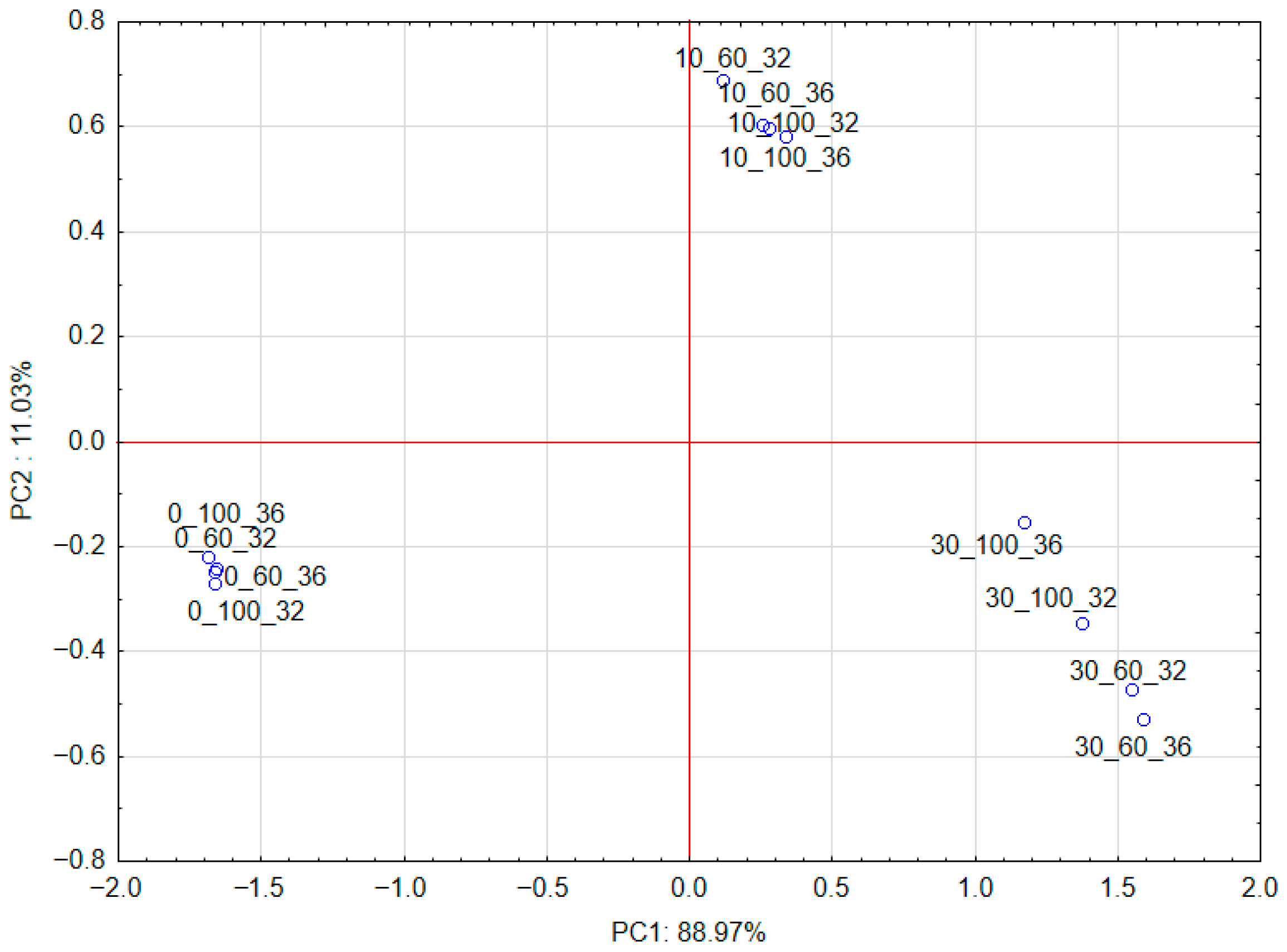

2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.4. Efficiency of the Extrusion Cooking Process

2.5. Energy Consumption of the Extrusion Cooking Process

2.6. Water Absorption Index (WAI)

2.7. Water Solubility Index (WSI)

2.8. Bulk Density of the Snack Pellets

2.9. Durability of the Snack Pellets

3. Discussion

3.1. Free Radical Scavenging Activity, Total Phenolic Content and Chromatographic Analysis of Free Phenolic Acids

3.2. Extrusion Cooking Parameters

3.3. Selected Physical Properties of Extruded Pellets

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials Used in the Production of Pellets

4.2. Preparation of Mixtures and Extrusion Cooking Process

4.3. Efficiency of the Extrusion Cooking Process

4.4. Energy Consumption of the Extrusion Cooking Process

- SME—specific mechanical energy (kWh/kg);

- n—screw rotational speed (RPM);

- nm—maximum screw speed of the extruder;

- O—motor load (%);

- P—rated motor power as indicated on the control panel (kW);

- Q—extrusion throughput (kg/h).

4.5. Bulk Density of Snack Pellets

4.6. Durability of Extrudates

4.7. Water Absorption Index of Snack Pellets

4.8. The Water Solubility Index of Snack Pellets

4.9. Preparation of Extracts—Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

4.10. Free Radical Scavenging Activity—DPPH Method

4.11. Total Content of Polyphenolic Compounds (TPC) with Use of Folin–Ciocalteu Method

4.12. LC-ESI-MS/MS Analysis of Phenolic Acids

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prather, C.M.; Laws, A.N. Insects as a Piece of the Puzzle to Mitigate Global Problems: An Opportunity for Ecologists. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2018, 26, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambridge University Press. Scientific Concepts of Functional Foods in Europe Consensus Document. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, S1–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates-Doerr, E. The World in a Box? Food Security, Edible Insects, and “One World, One Health” Collaboration. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 129, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weru, J.; Chege, P.; Kinyuru, J. Nutritional Potential of Edible Insects: A Systematic Review of Published Data. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2021, 41, 2015–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ramos, J.A.; Rojas, M.G.; Dossey, A.T.; Berhow, M. Self-Selection of Food Ingredients and Agricultural by-Products by the House Cricket, Acheta domesticus (Orthoptera: Gryllidae): A Holistic Approach to Develop Optimized Diets. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-González, R.; Fernández-López, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J.A.; Viuda-Martos, M. Effect of Drying Processes in the Chemical, Physico-Chemical, Techno-Functional and Antioxidant Properties of Flours Obtained from House Cricket (Acheta domesticus). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1451–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, M.F.; Martínez, J.; Barrionuevo, A.; Rojas, M.; Carrillo, W. Functional, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Cricket Protein Concentrate (Gryllus assimilis). Biology 2022, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, E. Evaluating the Functional Characteristics of Certain Insect Flours (Non-Defatted/Defatted Flour) and Their Protein Preparations. Molecules 2022, 27, 6339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, K.G.; Kotao, T.; Lopez, I.; Koeppel, J.; Goldstein, A.; Samuel, L.; Stopler, M. Acceptance of Using Cricket Flour as a Low Carbohydrate, High Protein, Sustainable Substitute for All-Purpose Flour in Muffins. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2020, 18, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, A.; Oliva, N.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Lorini, C.; Cini, E. Assessment of the Rheological Properties and Bread Characteristics Obtained by Innovative Protein Sources (Cicer arietinum, Acheta domesticus, Tenebrio molitor): Novel Food or Potential Improvers for Wheat Flour? LWT 2020, 118, 108867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, S.; Mikulec, A.; Mickowska, B.; Skotnicka, M.; Mazurek, A. Wheat Bread Supplementation with Various Edible Insect Flours. Influence of Chemical Composition on Nutritional and Technological Aspects. LWT 2022, 159, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementing Regulation—2023/5—EN—EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2023/5/oj/eng (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (NDA); Turck, D.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of Partially Defatted House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Powder as a Novel Food Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igual, M.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J. Effect of Acheta domesticus (House Cricket) Addition on Protein Content, Colour, Texture, and Extrusion Parameters of Extruded Products. J. Food Eng. 2020, 282, 110032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprzak-Drozd, K.; Oniszczuk, T.; Kowalska, I.; Mołdoch, J.; Combrzyński, M.; Gancarz, M.; Dobrzański, B.; Kondracka, A.; Oniszczuk, A. Effect of the Production Parameters and In Vitro Digestion on the Content of Polyphenolic Compounds, Phenolic Acids, and Antiradical Properties of Innovative Snacks Enriched with Wild Garlic (Allium ursinum L.) Leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, M.; Kasprzak, K.; Wójtowicz, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Nowak, R.; Waksmundzka-Hajnos, M.; Combrzyński, M.; Gancarz, M.; Kowalska, I.; Krajewska, A.; et al. Polyphenol Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Instant Gruels Enriched with Lycium barbarum L. Fruit. Molecules 2020, 25, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bear, C. Making Insects Tick: Responsibility, Attentiveness and Care in Edible Insect Farming. Environ. Plan. E 2021, 4, 1010–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, F.; Proksch, P.; Fiedler, K. Flavonoid Sequestration by the Common Blue Butterfly Polyommatus icarus: Quantitative Intraspecific Variation in Relation to Larval Hostplant, Sex and Body Size. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2001, 29, 875–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.O. Insect Cuticular Sclerotization: A Review. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 40, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nino, M.C.; Reddivari, L.; Osorio, C.; Kaplan, I.; Liceaga, A.M. Insects as a Source of Phenolic Compounds and Potential Health Benefits. J. Insects Food Feed. 2021, 7, 1077–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F.; Valentão, P.; Pereira, J.A.; Bento, A.; Noites, A.; Seabra, R.M.; Andrade, P.B. HPLC-DAD-MS/MS-ESI Screening of Phenolic Compounds in Pieris brassicae L. Reared on Brassica rapa var. rapa L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F.; Fernandes, F.; Pereira, D.M.; Pereira, J.A.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B. Phenolics Metabolism in Insects: Pieris brassicae− Brassica oleracea var. costata Ecological Duo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 9035–9043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musundire, R.; Zvidzai, C.J.; Chidewe, C.; Ngadze, R.T.; Macheka, L.; Manditsera, F.A.; Mubaiwa, J.; Masheka, A. Nutritional and Bioactive Compounds Composition of Eulepida Mashona, an Edible Beetle in Zimbabwe. J. Insects Food Feed. 2016, 2, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musundire, R.; Zvidzai, C.J.; Chidewe, C.; Samende, B.K.; Manditsera, F.A. Nutrient and Anti-Nutrient Composition of Henicus whellani (Orthoptera: Stenopelmatidae), an Edible Ground Cricket, in South-Eastern Zimbabwe. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2014, 34, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, C.; Ono, H.; Meng, Y.; Shimada, T.; Daimon, T. Flavonoids from the Cocoon of Rondotia menciana. Phytochemistry 2013, 94, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, M.; Bianchi, E.; Vigani, B.; Sánchez-Espejo, R.; Spano, M.; Totaro Fila, C.; Mannina, L.; Viseras, C.; Rossi, S.; Sandri, G. Nutritional and Functional Properties of Novel Italian Spray-Dried Cricket Powder. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant Flavonoids: Classification, Distribution, Biosynthesis, and Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielińska, E.; Pankiewicz, U.; Sujka, M. Nutritional, Physiochemical, and Biological Value of Muffins Enriched with Edible Insects Flour. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H.-J.; Kim, S.-R.; Lee, K.-S.; Park, S.; Kang, S.C. Antioxidant Activity of Various Solvent Extracts from Allomyrina dichotoma (Arthropoda: Insecta) Larvae. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2010, 99, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Gumienna, M.; Rybicka, I.; Górna, B.; Sarbak, P.; Dziedzic, K.; Kmiecik, D. Nutritional Value and Biological Activity of Gluten-Free Bread Enriched with Cricket Powder. Molecules 2021, 26, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Zhang, C.; Bi, J.; Zhu, F.; Qu, M.; Yang, Q. Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Compounds of Holotrichia parallela Motschulsky Extracts. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1885–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro del Hierro, J.; Gutiérrez-Docio, A.; Otero, P.; Reglero, G.; Martin, D. Characterization, Antioxidant Activity, and Inhibitory Effect on Pancreatic Lipase of Extracts from the Edible Insects Acheta domesticus and Tenebrio molitor. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-Birman, T.; Raften, G.; Lesmes, U. Effects of Thermal Treatments on the Colloidal Properties, Antioxidant Capacity and in-Vitro Proteolytic Degradation of Cricket Flour. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 79, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiiru, S.M.; Kinyuru, J.N.; Kiage, B.N.; Martin, A.; Marel, A.-K.; Osen, R. Extrusion Texturization of Cricket Flour and Soy Protein Isolate: Influence of Insect Content, Extrusion Temperature, and Moisture-Level Variation on Textural Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 4112–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.; Cunha, L.M.; García-Segovia, P.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; Igual, M. Effect of the House Cricket (Acheta domesticus) Inclusion and Process Temperature on Extrudate Snack Properties. J. Insects Food Feed. 2021, 7, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, H.; Van Der Borght, M.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Claes, J. Rheological Characterization of Chapatti (Roti) Enriched with Flour or Paste of House Crickets (Acheta domesticus). Foods 2021, 10, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboge, D.O.; Orinda, M.A.; Konyole, S.O. Effect of Partial Substitution of Soybean Flour with Cricket Flour on the Nutritional Composition, in Vitro-Protein Digestibility and Functional Properties of Complementary Porridge Flour. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. Effect of Fresh Beetroot Application and Processing Conditions on Some Quality Features of New Type of Potato-Based Snacks. LWT 2021, 141, 110919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, A.; Wójtowicz, A.; Oniszczuk, T. Process Efficiency and Energy Consumption During the Extrusion of Potato and Multigrain Formulations. Agric. Eng. 2018, 22, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrus, M.; Combrzyński, M.; Biernacka, B.; Wójtowicz, A.; Milanowski, M.; Kupryaniuk, K.; Gancarz, M.; Soja, J.; Różyło, R. Fresh Broccoli in Fortified Snack Pellets: Extrusion-Cooking Aspects and Physical Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. Possibility to Save Water and Energy by Application of Fresh Vegetables to Produce Supplemented Potato-Based Snack Pellets. Processes 2020, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójtowicz, A.; Combrzyński, M.; Biernacka, B.; Oniszczuk, T.; Mitrus, M.; Różyło, R.; Gancarz, M.; Oniszczuk, A. Application of Edible Insect Flour as a Novel Ingredient in Fortified Snack Pellets: Processing Aspects and Physical Characteristics. Processes 2023, 11, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushkova, M.; Simitchiev, A.; Petrova, T.; Menkov, N.; Desseva, I.; Mihaylova, D. Physical and Functional Characteristics of Extrudates Prepared from Quinoa Enriched with Goji Berry. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, J.; Combrzyński, M.; Oniszczuk, T.; Gancarz, M.; Oniszczuk, A. Extrusion-Cooking Aspects and Physical Characteristics of Snacks Pellets with Addition of Selected Plant Pomace. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.A.; Kumar, P. Fenugreek: A Review on Its Nutraceutical Properties and Utilization in Various Food Products. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagci, S.; Calıskan, R.; Gunes, Z.S.; Capanoglu, E.; Tomas, M. Impact of Tomato Pomace Powder Added to Extruded Snacks on the in Vitro Gastrointestinal Behaviour and Stability of Bioactive Compounds. Food Chem. 2022, 368, 130847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardhi, S.D.; Singh, B.; Nayik, G.A.; Dar, B.N. Evaluation of Functional Properties of Extruded Snacks Developed from Brown Rice Grits by Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combrzyński, M.; Wójtowicz, A.; Biernacka, B.; Oniszczuk, T.; Mitrus, M.; Soja, J.; Różyło, R.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Kasprzak-Drozd, K.; Oniszczuk, A. Possibility of Water Saving in Processing of Snack Pellets by the Application of Fresh Lucerne Sprouts: Selected Aspects and Nutritional Characteristics. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Combrzyński, M.; Biernacka, B.; Wójtowicz, A.; Kupryaniuk, K.; Oniszczuk, T.; Mitrus, M.; Różyło, R.; Gancarz, M.; Stasiak, M.; Kasprzak-Drozd, K. Analysis of the Extrusion-Cooking Process and Selected Physical Properties of Snack Pellets with the Addition of Fresh Kale. Int. Agrophys. 2023, 37, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cricket Powder Content | Production Parameters | Total Phenolic Content [μg GAE/g dw] |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 67.5 ± 2.7 b |

| 10% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 81.0 ± 0.6 c |

| 10% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 79.5 ± 9.4 bc |

| 10% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 84.8 ± 4.0 c |

| 30% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 207.3 ± 65.3 d |

| 30% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 212.3 ± 12.9 d |

| 30% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 191.0 ± 14.7 d |

| 30% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 169.7 ± 19.3 d |

| 0% | 32% moisture, 60 RPM | 19.1 ± 0.2 a |

| 0% | 36% moisture, 60 RPM | 21.7 ± 0.5 a |

| 0% | 32% moisture, 100 RPM | 23.1 ± 0.3 a |

| 0% | 36% moisture, 100 RPM | 21.8 ± 0.5 a |

| Compound | TR (min) | Pellets Without Cricket Powder [mg/100 g dw] | Pellets with 30% Addition of Cricket Powder [mg/100 g dw] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 5.10 | 0.60 ± 0.0220 | 0.605 ± 0.0124 |

| Chlorogenic acid | 6.40 | 17.31 ± 0.0761 | 17.33 ± 0.1178 |

| Caffeic acid | 6.90 | 1.12 ± 0.0320 | 1.127 ± 0.03411 |

| Syringic acid | 7.14 | not detected | 0.05 ± 0.0021 |

| 4-OH-benzoic acid | 7.29 | not detected | 0.09 ± 0.0015 |

| Vanillic acid | 7.46 | 0.83 ± 0.0210 | not detected |

| p-Coumaric acid | 9.28 | not detected | 0.02 ± 0.0010 |

| Sinapic acid | 9.75 | not detected | 0.01→0.0005 |

| Ferulic acid | 9.90 | 0.264 ± 0.0119 | 0.304 ± 0.0147 |

| House Cricket Powder Addition [%] | Screw Rotation [RPM] | Moisture [%] | Q [kg/h] | SME [kWh/kg] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 60 | 32 | 20.08 ± 0.37 a | 0.038 ± 0.001 e |

| 36 | 21.84 ± 0.24 b | 0.034 ± 0.000 e | ||

| 100 | 32 | 34.08 ± 1.25 d | 0.016 ± 0.001 ab | |

| 36 | 36.16 ± 0.28 e | 0.022 ± 0.000 bc | ||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 20.64 ± 0.00 ab | 0.053 ± 0.000 f |

| 36 | 20.48 ± 0.14 a | 0.048 ± 0.000 f | ||

| 100 | 32 | 30.68 ± 0.25 c | 0.029 ± 0.000 cde | |

| 36 | 33.36 ± 0.24 d | 0.023 ± 0.000 bcd | ||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 20.00 ± 0.28 a | 0.017 ± 0.000 ab |

| 36 | 20.96 ± 0.50 ab | 0.031 ± 0.010 de | ||

| 100 | 32 | 29.76 ± 0.24 c | 0.013 ± 0.001 ab | |

| 36 | 33.68 ± 0.14 d | 0.010 ± 0.006 a |

| House Cricket Powder Addition [%] | Screw Rotation [RPM] | Moisture [%] | WAI [g/g] | WSI [%] | Bulk Density [kg/m3] | Durability [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 60 | 32 | 3.23 ± 0.00 abc | 8.24 ± 0.01 c | 420.70 ± 5.33 f | 98.14 ± 0.16 cdef |

| 36 | 3.90 ± 0.01 abcde | 17.21 ± 0.00 d | 384.64 ± 4.40 e | 98.26 ± 0.42 def | ||

| 100 | 32 | 3.98 ± 0.00 bcde | 7.54 ± 0.01 bc | 425.23 ± 13.31 f | 98.71 ± 0.43 f | |

| 36 | 4.07 ± 0.00 cde | 18.35 ± 0.00 d | 416.72 ± 5.40 f | 98.40 ± 0.34 ef | ||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 4.53 ± 0.04 de | 3.81 ± 1.00 ab | 328.23 ± 15.12 cd | 97.41 ± 0.28 bcdef |

| 36 | 3.03 ± 0.05 abc | 3.67 ± 2.29 ab | 310.07 ± 1.69 bc | 97.03 ± 0.58 abcdef | ||

| 100 | 32 | 4.72 ± 0.12 e | 3.67 ± 0.91 ab | 394.93 ± 1.50 e | 96.43 ± 0.75 abcde | |

| 36 | 2.81 ± 0.14 ab | 3.76 ± 1.67 ab | 347.13 ± 2.47 d | 96.76 ± 0.45 abcdef | ||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 3.31 ± 0.09 abc | 2.90 ± 1.33 a | 263.53 ± 1.40 a | 95.21 ± 0.27 a |

| 36 | 3.52 ± 1.38 abcd | 6.14 ± 3.01 abc | 262.03 ± 1.81 a | 96.20 ± 0.51 abc | ||

| 100 | 32 | 3.41 ± 0.08 abcd | 2.57 ± 1.79 a | 298.03 ± 1.00 b | 95.82 ± 0.22 ab | |

| 36 | 2.75 ± 0.08 a | 3.43 ± 0.38 ab | 266.67 ± 2.78 a | 96.42 ± 1.84 abcd |

| Raw Materials | Control Sample | 10% Insect Powder | 30% Insect Powder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insect powder (%) | 0 | 10 | 30 |

| Potato starch (%) | 82 | 72 | 52 |

| Potato flakes (%) | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Vegetable oil (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sugar (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Salt (%) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| House Cricket Powder Addition [%] | Screw Rotation [RPM] | Moisture [%] | Temperature of Section I [°C] | Temperature of Section II [°C] | Temperature of Section III [°C] | Temperature of Section IV [°C] | Extruder Die [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 60 | 32 | 44.90 ± 0.53 | 67.11 ± 0.35 | 66.09 ± 0.64 | 61.80 ± 0.41 | 62.60 ± 0.69 |

| 36 | 47.99 ± 0.27 | 65.69 ± 0.32 | 66.50 ± 0.27 | 62.90 ± 0.11 | 64.51 ± 0.14 | ||

| 100 | 32 | 45.11 ± 0.26 | 68.10 ± 0.67 | 67.21 ± 0.80 | 63.81 ± 0.34 | 63.20 ± 0.21 | |

| 36 | 49.49 ± 0.37 | 66.10 ± 0.10 | 66.80 ± 0.28 | 63.11 ± 0.16 | 62.60 ± 0.17 | ||

| 10 | 60 | 32 | 48.71 ± 0.19 | 65.70 ± 0.29 | 67.00 ± 0.17 | 64.61 ± 0.55 | 64.91 ± 0.13 |

| 36 | 47.09 ± 0.28 | 64.80 ± 0.15 | 66.31 ± 0.27 | 64.40 ± 0.83 | 64.59 ± 0.66 | ||

| 100 | 32 | 47.19 ± 0.11 | 68.00 ± 0.43 | 66.89 ± 0.33 | 64.91 ± 0.26 | 62.51 ± 0.28 | |

| 36 | 48.51 ± 0.11 | 65.49 ± 0.29 | 66.30 ± 0.20 | 64.20 ± 0.45 | 62.00 ± 0.19 | ||

| 30 | 60 | 32 | 45.80 ± 0.25 | 65.30 ± 0.69 | 66.29 ± 0.19 | 63.90 ± 0.42 | 64.89 ± 0.21 |

| 36 | 46.00 ± 0.28 | 64.61 ± 0.18 | 66.20 ± 0.44 | 64.19 ± 0.43 | 64.80 ± 0.14 | ||

| 100 | 32 | 44.90 ± 0.64 | 66.79 ± 0.58 | 66.30 ± 0.12 | 64.50 ± 0.13 | 61.90 ± 0.31 | |

| 36 | 47.39 ± 0.63 | 65.39 ± 0.61 | 65.91 ± 0.14 | 63.89 ± 0.15 | 62.50 ± 0.78 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Combrzyński, M.; Soja, J.; Staniak, M.; Biernacka, B.; Wojtunik-Kulesza, K.; Gancarz, M.; Oniszczuk, T.; Kręcisz, M.; Szponar, J.; Oniszczuk, A. Influence of Extrusion Cooking Parameters on Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of Potato-Based Snack Pellets Enriched with Cricket Powder. Molecules 2025, 30, 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234612

Combrzyński M, Soja J, Staniak M, Biernacka B, Wojtunik-Kulesza K, Gancarz M, Oniszczuk T, Kręcisz M, Szponar J, Oniszczuk A. Influence of Extrusion Cooking Parameters on Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of Potato-Based Snack Pellets Enriched with Cricket Powder. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234612

Chicago/Turabian StyleCombrzyński, Maciej, Jakub Soja, Michał Staniak, Beata Biernacka, Karolina Wojtunik-Kulesza, Marek Gancarz, Tomasz Oniszczuk, Magdalena Kręcisz, Jarosław Szponar, and Anna Oniszczuk. 2025. "Influence of Extrusion Cooking Parameters on Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of Potato-Based Snack Pellets Enriched with Cricket Powder" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234612

APA StyleCombrzyński, M., Soja, J., Staniak, M., Biernacka, B., Wojtunik-Kulesza, K., Gancarz, M., Oniszczuk, T., Kręcisz, M., Szponar, J., & Oniszczuk, A. (2025). Influence of Extrusion Cooking Parameters on Antioxidant Activity and Physical Properties of Potato-Based Snack Pellets Enriched with Cricket Powder. Molecules, 30(23), 4612. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234612