From Biomass to Efficient Lipid Recovery: Choline-Based Ionic Liquids and Microwave Extraction of Chlorella vulgaris

Abstract

1. Introduction

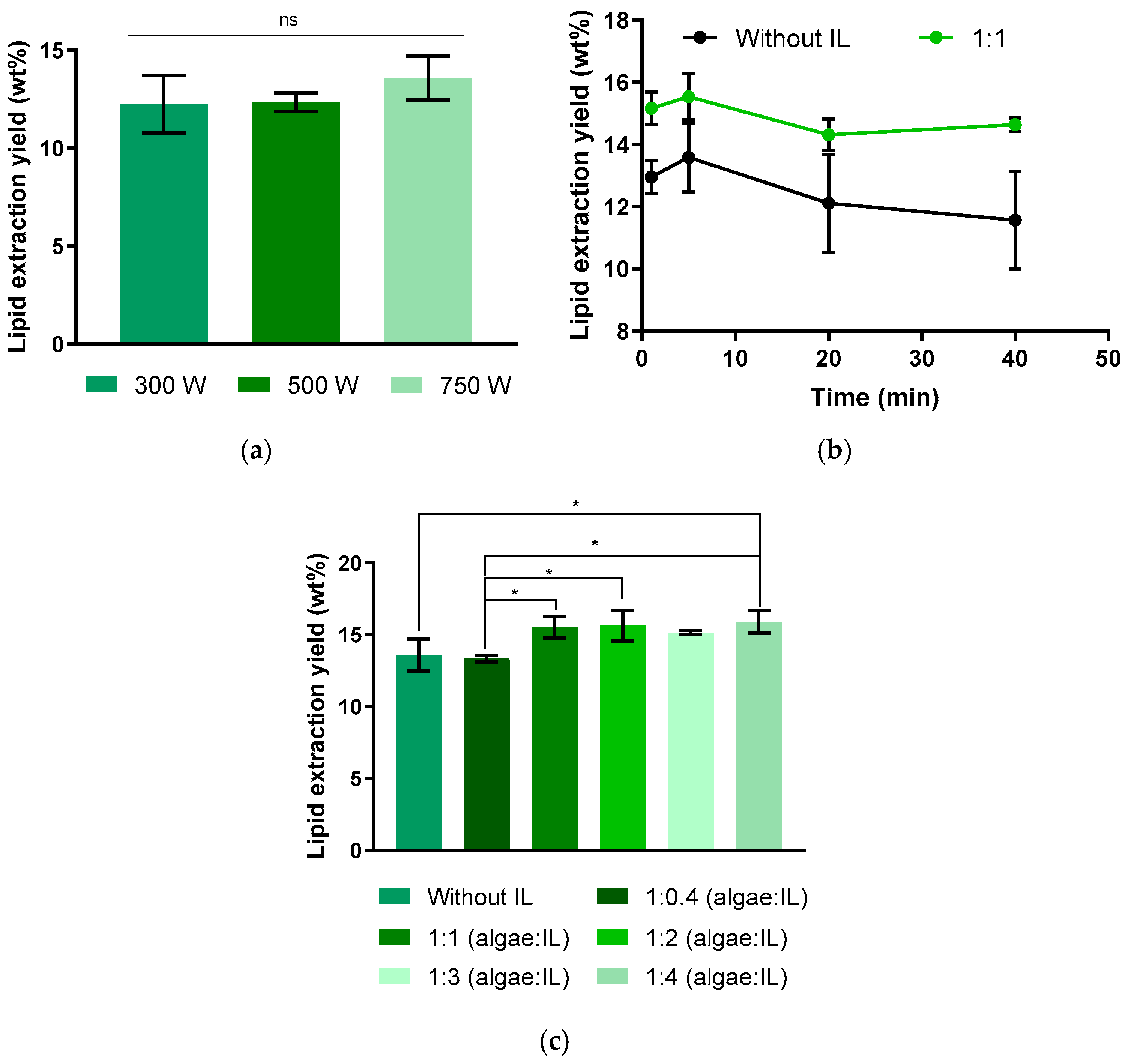

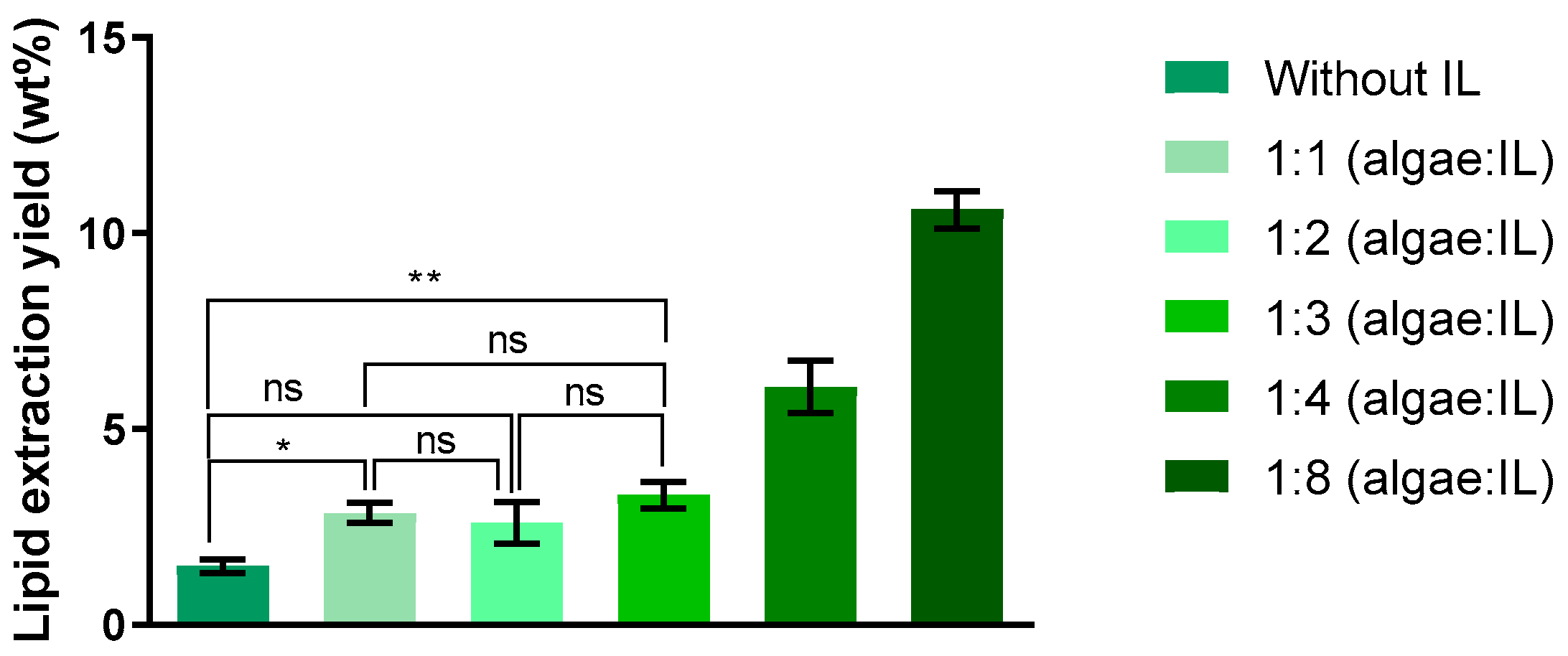

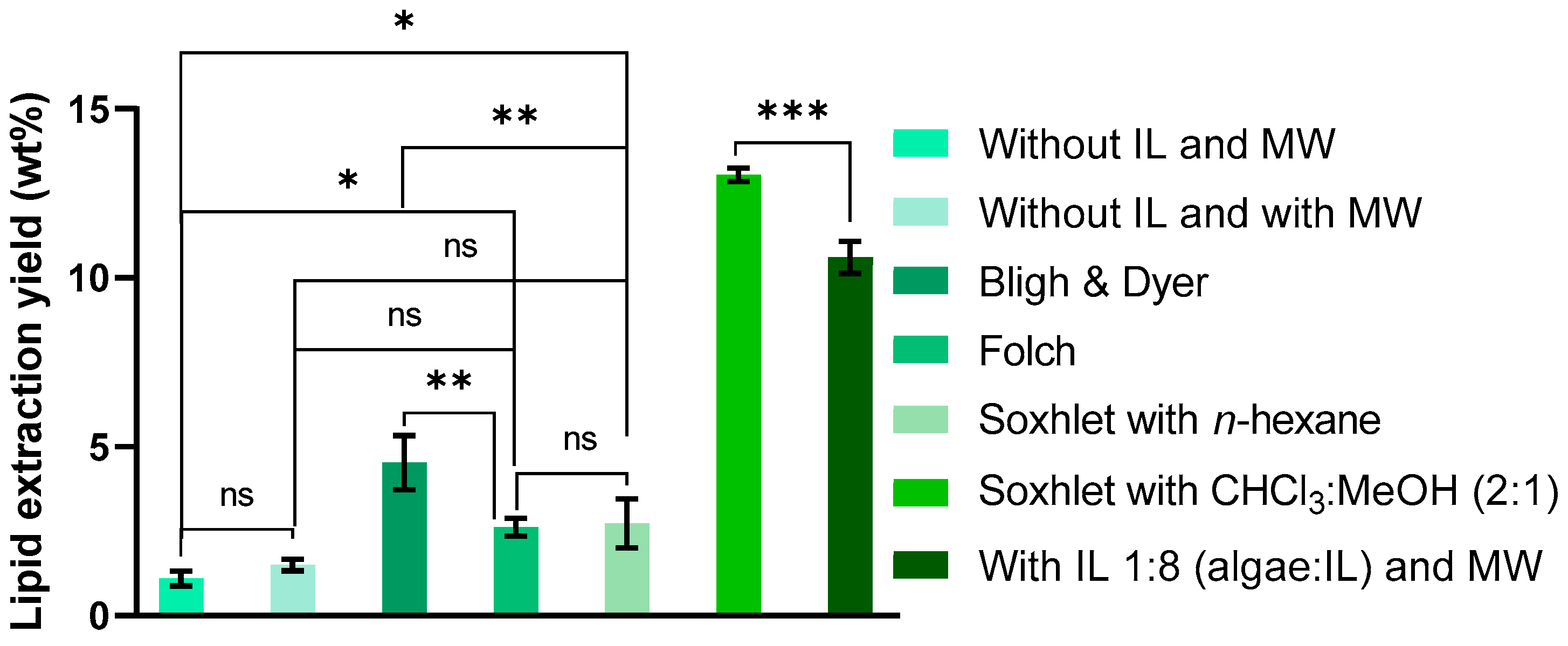

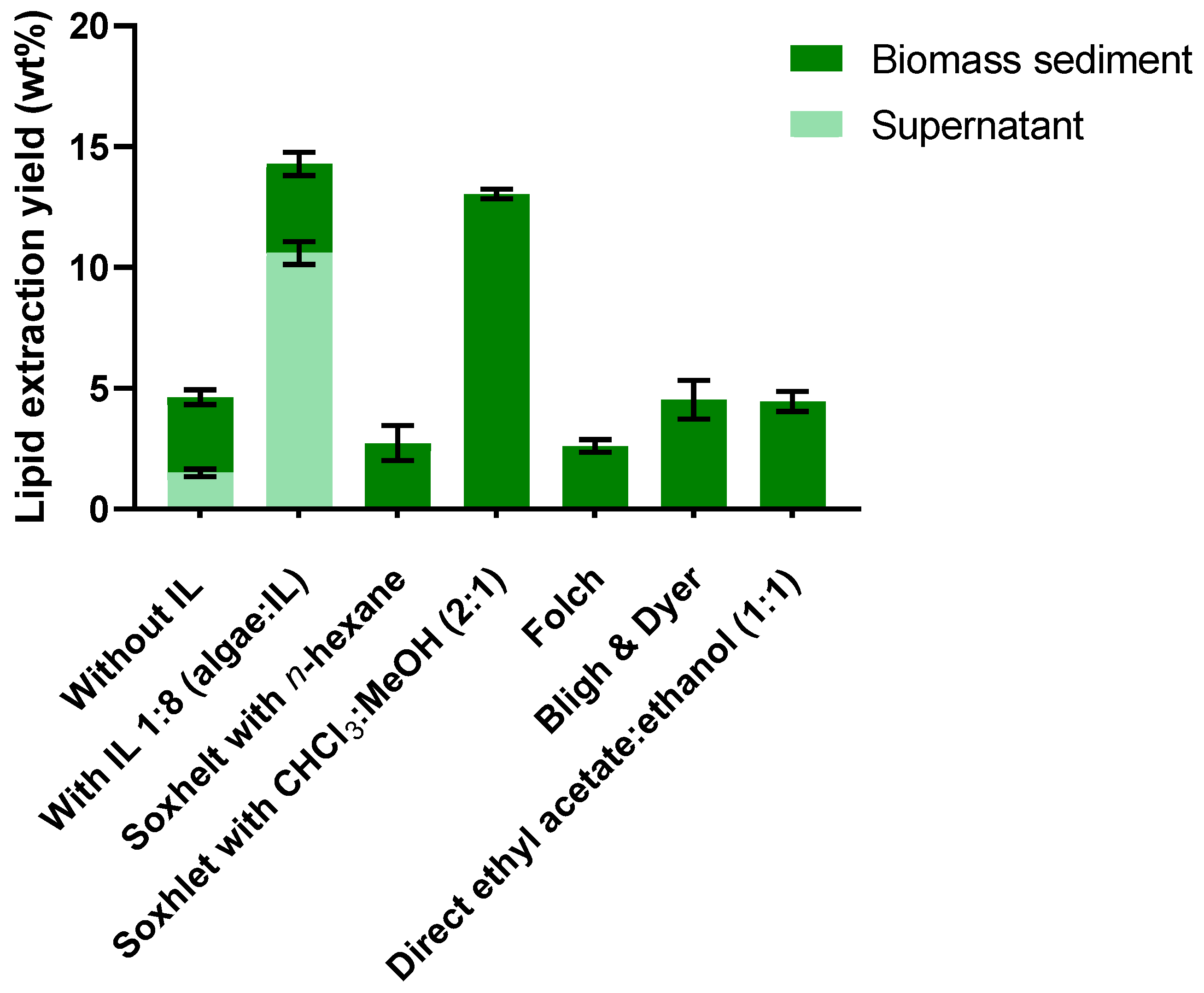

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Lipid Extraction Using Conventional Methods

2.2. Lipid Extraction from Biomass Residue (Sediment) with Chloroform/Methanol (1:1)

2.3. Lipid Extraction from IL Phase (Supernatant)

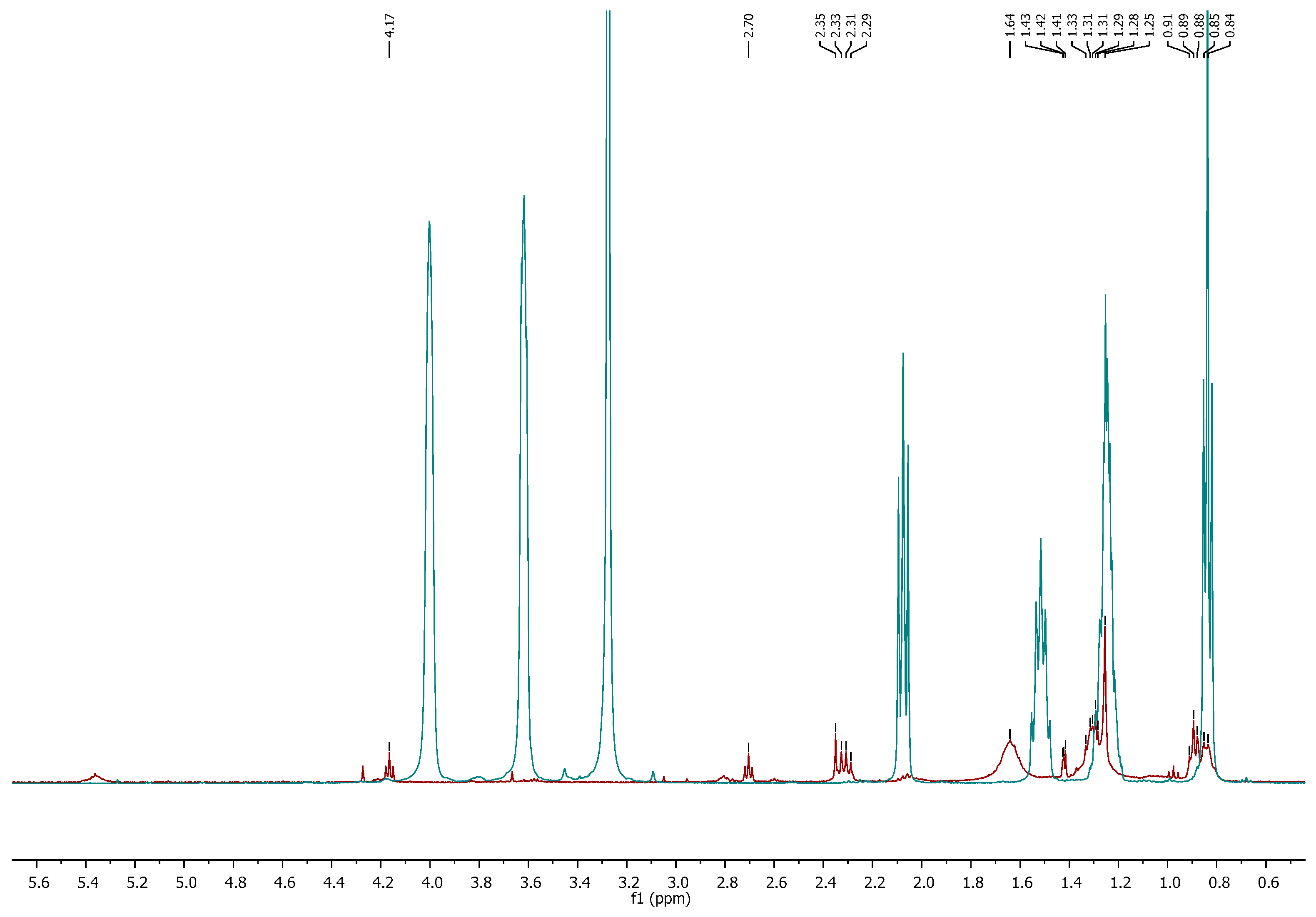

Characterization of the Extract by 1H NMR

2.4. Total Lipid Extraction (Supernatant and Biomass Sediment)

2.5. Recovery of Ionic Liquid

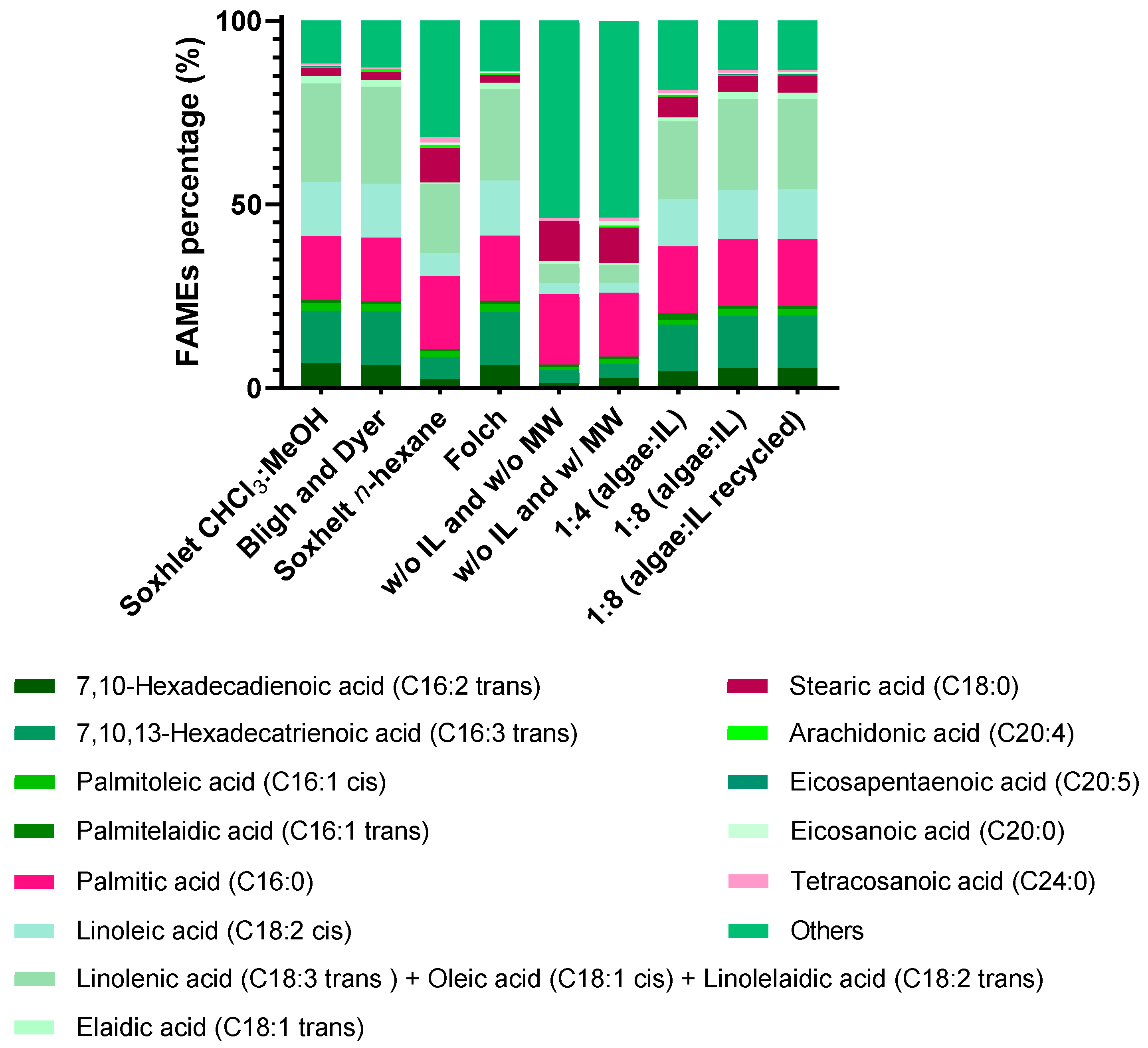

2.6. Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) Composition Analysis

2.6.1. FAMEs Composition Obtained from IL Phase (Supernatant)

2.6.2. FAMEs Total Composition Obtained (Supernatant and Biomass Sediment)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of Ionic Liquid

3.2.1. Synthesis of [N1 1 2OH 2OH]Cl

3.2.2. Synthesis of [N1 1 2OH 2OH][C6H11O2] via Metathesis Reaction

3.3. Analytical Techniques

3.3.1. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

3.3.2. Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR-ATR)

3.3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.4. Lipid Extraction Using Conventional Methods

3.4.1. Soxhlet Extraction Method

3.4.2. Folch Extraction Method

3.4.3. Bligh & Dyer Extraction Method

3.5. Pretreatment of Chlorella vulgaris with IL and Microwave-Assisted Extraction

3.6. Lipid Extraction from Biomass Residue (Sediment)

3.6.1. Lipid Extraction from Biomass Residue (Sediment) Using Chloroform/Methanol (1:1 v/v) Mixture

3.6.2. Lipid Extraction from Biomass Residue (Sediment) Using Ethyl Acetate/Ethanol (1:1 v/v) Mixture

3.7. Lipid Extraction from IL Phase (Supernatant)

3.8. Recovery of Ionic Liquid

3.9. Transesterification

3.10. Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) Composition Analysis

3.11. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Safi, C.; Camy, S.; Frances, C.; Varela, M.M.; Badia, E.C.; Pontalier, P.-Y.; Vaca-Garcia, C. Extraction of Lipids and Pigments of Chlorella vulgaris by Supercritical Carbon Dioxide: Influence of Bead Milling on Extraction Performance. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Martins, A.P.; Pinto, C.A.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Cao, H.; Xiao, J.; Barba, F.J. Extraction of Lipids from Microalgae Using Classical and Innovative Approaches. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, K.; Sandal, N.; Sahoo, P.K. A Comprehensive Review on Chlorella-Its Composition, Health Benefits, Market and Regulatory Scenario. Pharma Innov. J. 2018, 7, 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza, M.; Santoyo, S.; Jaime, L.; Avalo, B.; Cifuentes, A.; Reglero, G.; García-Blairsy Reina, G.; Señoráns, F.J.; Ibáñez, E. Comprehensive Characterization of the Functional Activities of Pressurized Liquid and Ultrasound-Assisted Extracts from Chlorella vulgaris. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Wei, S.; Liu, Z.; Fan, X.; Sun, Q.; Xia, Q.; Liu, S.; Hao, J.; Deng, C. Non-Thermal Processing Technologies for the Recovery of Bioactive Compounds from Marine by-Products. LWT 2021, 147, 111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-A.; Oh, Y.-K.; Jeong, M.-J.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.-S.; Park, J.-Y. Effects of Ionic Liquid Mixtures on Lipid Extraction from Chlorella vulgaris. Renew. Energy 2014, 65, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, T.Q.; Procter, K.; Simmons, B.A.; Subashchandrabose, S.; Atkin, R. Low Cost Ionic Liquid–Water Mixtures for Effective Extraction of Carbohydrate and Lipid from Algae. Faraday Discuss. 2018, 206, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, T.; Morya, R.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Kumar, D.; Soam, S.; Kumar, R.; Patel, A.K.; Kim, S.-H. Microalgae Biomass Deconstruction Using Green Solvents: Challenges and Future Opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.S.; Ferreira, S.S.; Correia, A.; Vilanova, M.; Silva, T.H.; Coimbra, M.A.; Nunes, C. Reserve, Structural and Extracellular Polysaccharides of Chlorella vulgaris: A Holistic Approach. Algal Res. 2020, 45, 101757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, S.S.; Filho, R.M. Recent Advances in Lipid Extraction Using Green Solvents. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 133, 110289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, R.; Danquah, M.K.; Webley, P.A. Extraction of Oil from Microalgae for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 709–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, L.M. APPENDIX 3—Seed Food Reserves and Their Accumulation; Srivastava, L.M., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 503–520. ISBN 978-0-12-660570-9. [Google Scholar]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Their Health Benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibi, G. Inhibition of Lipase and Inflammatory Mediators by Chlorella Lipid Extracts for Antiacne Treatment. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2015, 6, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiels, K.; Tsoupras, A.; Lordan, R.; Nasopoulou, C.; Zabetakis, I.; Murray, P.; Saha, S.K. Bioactive Lipids of Marine Microalga Chlorococcum sp. SABC 012504 with Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Thrombotic Activities. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agregán, R.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Franco, D.; Carballo, J.; Barba, F.J.; Lorenzo, J.M. Antioxidant Potential of Extracts Obtained from Macro-(Ascophyllum Nodosum, Fucus Vesiculosus and Bifurcaria Bifurcata) and Micro-Algae (Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina Platensis) Assisted by Ultrasound. Medicines 2018, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, R.K.; Srivastava, A.; Kayastha, A.M.; Nath, G.; Singh, S.P. Antibacterial Potential of γ-Linolenic Acid from Fischerella sp. Colonizing Neem Tree Bark. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 22, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodbasha, M.; Edachery, B.; Nooruddin, T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-W. An Evidence of C16 Fatty Acid Methyl Esters Extracted from Microalga for Effective Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Property. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 115, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remize, M.; Brunel, Y.; Silva, J.L.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Filaire, E. Microalgae N-3 PUFAs Production and Use in Food and Feed Industries. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, U.N. Arachidonic Acid and Other Unsaturated Fatty Acids and Some of Their Metabolites Function as Endogenous Antimicrobial Molecules: A Review. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibi, G.; Rabina, S. Inhibition of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators and Cytokines by Chlorella vulgaris Extracts. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desbois, A.P.; Mearns-Spragg, A.; Smith, V.J. A Fatty Acid from the Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Is Antibacterial Against Diverse Bacteria Including Multi-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA). Mar. Biotechnol. 2009, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineshkumar, R.; Narendran, R.; Jayasingam, P.; Sampathkumar, P. Cultivation and Chemical Composition of Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris and Its Antibacterial Activity against Human Pathogens. J. Aquac. Mar. Biol. 2017, 5, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffell, S.E.; Müller, K.M.; McConkey, B.J. Comparative Assessment of Microalgal Fatty Acids as Topical Antibiotics. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, T.A.; Zabetakis, I.; Tsoupras, A.; Medina, I.; Costa, M.; Silva, J.; Neves, B.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.R. Microalgal Lipid Extracts Have Potential to Modulate the Inflammatory Response: A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itariu, B.K.; Zeyda, M.; Hochbrugger, E.E.; Neuhofer, A.; Prager, G.; Schindler, K.; Bohdjalian, A.; Mascher, D.; Vangala, S.; Schranz, M.; et al. Long-Chain N−3 PUFAs Reduce Adipose Tissue and Systemic Inflammation in Severely Obese Nondiabetic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial123. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.G.; Contaifer, D.; Madurantakam, P.; Carbone, S.; Price, E.T.; Van Tassell, B.; Brophy, D.F.; Wijesinghe, D.S. Dietary Bioactive Fatty Acids as Modulators of Immune Function: Implications on Human Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirian, F.; Dadkhah, M.; Moradi-kor, N.; Obeidavi, Z. Effects of Spirulina Platensis Microalgae on Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Factors in Diabetic Rats. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018, 11, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustiar, A.A.; Rairat, T.; Zeng, M.; Praiboon, J. Effect of Different Extracting Solvents on Antioxidant Activity and Inhibitory Effect on Diabetic Enzymes of Chlorella vulgaris and Spirulina Platensis. J. Fish. Environ. 2022, 46, 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R.C.; Gracia Mateo, M.R.; O’Grady, M.N.; Guihéneuf, F.; Stengel, D.B.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Kerry, J.P.; Stanton, C. An Assessment of the Techno-Functional and Sensory Properties of Yoghurt Fortified with a Lipid Extract from the Microalga Pavlova Lutheri. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 37, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafarga, T. Effect of Microalgal Biomass Incorporation into Foods: Nutritional and Sensorial Attributes of the End Products. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Elnesr, S.S.; Farag, M.R.; El-Sabrout, K.; Alqaisi, O.; Dawood, M.A.O.; Soomro, H.; Abdelnour, S.A. Nutritional Significance and Health Benefits of Omega-3, -6 and -9 Fatty Acids in Animals. Anim. Biotechnol. 2022, 33, 1678–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.M.P.; Sotana de Souza, R.A.; Leon-Nino, A.D.; da Costa, J.D.A.; Tiburcio, R.S.; Nunes, T.A.; Sellare de Mello, T.C.; Kanemoto, F.T.; Saldanha-Corrêa, F.M.P.; Gianesella, S.M.F. Improvement in Microalgae Lipid Extraction Using a Sonication-Assisted Method. Renew. Energy 2013, 55, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei Motlagh, S.; Harun, R.; Awang Biak, D.R.; Hussain, S.A.; Omar, R.; Khezri, R.; Elgharbawy, A.A. Ionic Liquid-Based Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Lipid and Eicosapentaenoic Acid from Nannochloropsis Oceanica Biomass: Experimental Optimization Approach. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 2015–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, V.C.A.; Plechkova, N.V.; Seddon, K.R.; Rehmann, L. Disruption and Wet Extraction of the Microalgae Chlorella vulgaris Using Room-Temperature Ionic Liquids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soxhlet, F. von Die Gewichtsanalytische Bestimmung Des Milchfettes. Polytech. J. 1879, 232, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A Rapid Method of Total Lipid Extraction and Purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlanta (GA): Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (US) Toxicological Profile for Chloroform. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK609968/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Joshi, D.R.; Adhikari, N. An Overview on Common Organic Solvents and Their Toxicity. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2019, 28, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, S.S.; Ferreira, G.F.; Moreira, L.S.; Wolf Maciel, M.R.; Maciel Filho, R. Comparison of Several Methods for Effective Lipid Extraction from Wet Microalgae Using Green Solvents. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashed, M.; Aldeghaither, N.S.; Almutairi, S.Y.; Almutairi, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Alqahtani, T.; Almojathel, G.H.; Alnassar, N.A.; Alghadeer, S.M.; Alshehri, A.; et al. The Perils of Methanol Exposure: Insights into Toxicity and Clinical Management. Toxics 2024, 12, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Claux, O.; Abert-Vian, M.; Tabasso, S.; Cravotto, G.; Chemat, F. Towards Substitution of Hexane as Extraction Solvent of Food Products and Ingredients with No Regrets. Foods 2022, 11, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egesa, D.; Plucinski, P. Efficient Extraction of Lipids from Magnetically Separated Microalgae Using Ionic Liquids and Their Transesterification to Biodiesel. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matchim Kamdem, M.C.; Lai, N. Alkyl Carbamate Ionic Liquids for Permeabilization of Microalgae Biomass to Enhance Lipid Recovery for Biodiesel Production. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahidin, S.; Idris, A.; Shaleh, S.R.M. Ionic Liquid as a Promising Biobased Green Solvent in Combination with Microwave Irradiation for Direct Biodiesel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 206, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, K.S.; Davis, L.E.; McClellan, L.M.; Lillo, A.M.; Welsh, J.D.; Schmidt, E.N.; Sanders, C.K.; Lou, A.J.; Fox, D.T.; Koppisch, A.T. Evaluation of Ionic Liquids on Phototrophic Microbes and Their Use in Biofuel Extraction and Isolation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Smith, R.L.; Qi, X. Production of Biofuels and Chemicals with Ionic Liquids; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9400777108. [Google Scholar]

- Swatloski, R.P.; Spear, S.K.; Holbrey, J.D.; Rogers, R.D. Dissolution of Cellose with Ionic Liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 4974–4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.S.; Ibrahim, T.H.; Jabbar, N.A.; Khamis, M.I.; Nancarrow, P.; Mjalli, F.S. Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Recovery of Phenolic Compounds: Effect of Ionic Liquids Structure and Process Parameters. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 12398–12422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkert, A.; Marsh, K.N.; Pang, S.; Staiger, M.P. Ionic Liquids and Their Interaction with Cellulose. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6712–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xia, S.; Ma, P. Use of Ionic Liquids as ‘Green’ Solvents for Extractions. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2005, 80, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-A.; Lee, J.-S.; Oh, Y.-K.; Jeong, M.-J.; Kim, S.W.; Park, J.-Y. Lipid Extraction from Chlorella vulgaris by Molten-Salt/Ionic-Liquid Mixtures. Algal Res. 2014, 3, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Muppaneni, T.; Sun, Y.; Reddy, H.K.; Fu, J.; Lu, X.; Deng, S. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Lipids from Microalgae Using an Ionic Liquid Solvent [BMIM][HSO4]. Fuel 2016, 178, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Choi, Y.-K.; Park, J.; Lee, S.; Yang, Y.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, T.-J.; Hwan Kim, Y.; Lee, S.H. Ionic Liquid-Mediated Extraction of Lipids from Algal Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 109, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Kobayashi, D.; Nakamura, N.; Ohno, H. Direct Dissolution of Wet and Saliferous Marine Microalgae by Polar Ionic Liquids without Heating. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2013, 52, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mena, I.F.; Diaz, E.; Palomar, J.; Rodriguez, J.J.; Mohedano, A.F. Cation and Anion Effect on the Biodegradability and Toxicity of Imidazolium– and Choline–Based Ionic Liquids. Chemosphere 2020, 240, 124947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinho, D.A.S.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, P.M. Chapter 21—Improvement of New and Nontoxic Dianionic and Dicationic Ionic Liquids in Solubility of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. In Advances in Green and Sustainable Chemistry; Akhter Siddique, J., Ahmad, A., Jawaid, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 405–420. ISBN 978-0-323-95931-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, A.R.; Raposo, L.R.; Soromenho, M.R.C.; Agostinho, D.A.S.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R.; Reis, P.M. New Non-Toxic N-Alkyl Cholinium-Based Ionic Liquids as Excipients to Improve the Solubility of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Symmetry 2021, 13, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, D.A.S.; Santos, F.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, P.M. New Non-Toxic Biocompatible Dianionic Ionic Liquids That Enhance the Solubility of Oral Drugs from BCS Class II. J. Ion. Liq. 2021, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, D.A.S.; Jesus, A.R.; Silva, A.B.P.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, P.M. Improvement of New Dianionic Ionic Liquids vs Monoanionic in Solubility of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 110, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, W.; Jorge, T.F.; Martins, S.; Meireles, M.; Carolino, M.; Cruz, C.; Almeida, T.V.; Araújo, M.E.M. Toxicity of Ionic Liquids Prepared from Biomaterials. Chemosphere 2014, 104, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, A.R.; Soromenho, M.R.C.; Raposo, L.R.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R.; Reis, P.M. Enhancement of Water Solubility of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs by New Biocompatible N-Acetyl Amino Acid N-Alkyl Cholinium-Based Ionic Liquids. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 137, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos de Almeida, T.; Júlio, A.; Saraiva, N.; Fernandes, A.S.; Araújo, M.E.M.; Baby, A.R.; Rosado, C.; Mota, J.P. Choline-versus Imidazole-Based Ionic Liquids as Functional Ingredients in Topical Delivery Systems: Cytotoxicity, Solubility, and Skin Permeation Studies. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2017, 43, 1858–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.B.P.; Jesus, A.R.; Agostinho, D.A.S.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Paiva, A.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, P.M. Using Dicationic Ionic Liquids to Upgrade the Cytotoxicity and Solubility of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. J. Ion. Liq. 2023, 3, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppink, M.H.M.; Ventura, S.P.M.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Wijffels, R.H. Multiproduct Microalgae Biorefineries Mediated by Ionic Liquids. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shin, W.-S.; Jung, J.-Y.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, J.W.; Kwon, J.-H.; Yang, J.-W. Optimization of Variables Affecting the Direct Transesterification of Wet Biomass from Nannochloropsis Oceanica Using Ionic Liquid as a Co-Solvent. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 38, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Ghani, N.A.; Aminuddin, N.F.; Quraishi, K.S.; Azman, N.S.; Cravotto, G.; Leveque, J.-M. Microwave-Assisted Lipid Extraction from Chlorella vulgaris in Water with 0.5%–2.5% of Imidazolium Based Ionic Liquid as Additive. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; Alam, M.A.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Yuan, Z.; Huo, S.; Guo, Y.; Qin, L.; Ma, L. Repeated Utilization of Ionic Liquid to Extract Lipid from Algal Biomass. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2019, 2019, 9209210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, P.; Bernal, J.M.; Gómez, C.; Álvarez, E.; Markiv, B.; García-Verdugo, E.; Luis, S.V. Green Biocatalytic Synthesis of Biodiesel from Microalgae in One-Pot Systems Based on Sponge-like Ionic Liquids. Catal. Today 2020, 346, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Abd Ghani, N.; Aminuddin, N.F.; Quraishi, K.S.; Razafindramangarafara, B.L.; Baup, S.; Leveque, J.-M. Unexpected Acceleration of Ultrasonic-Assisted Iodide Dosimetry in the Catalytic Presence of Ionic Liquids. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 74, 105576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Shimizu, A. Effect of High Hydrostatic Pressure Treatment with Room-Temperature Ionic Liquid 1-Ethyl-3-Methylimidazolium Acetate—Dimethyl Sulfoxide Mixture on Lipid Extraction from Chlorella vulgaris. High Press. Res. 2022, 42, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R.E. Energy-Efficient Extraction of Fuel and Chemical Feedstocks from Algae. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Park, S.; Kim, M.H.; Choi, Y.-K.; Yang, Y.-H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.-S.; Song, K.-G.; Lee, S.H. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Lipids from Chlorella vulgaris Using [Bmim][MeSO4]. Biomass Bioenergy 2013, 56, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Orr, V.; Rehmann, L. Butanol Fermentation from Microalgae-Derived Carbohydrates after Ionic Liquid Extraction. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 206, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Lu, H.; Tu, S.-T.; Yan, J. Energy-Efficient Extraction of Fuel from Chlorella vulgaris by Ionic Liquid Combined with CO2 Capture. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahidin, S.; Idris, A.; Yusof, N.M.; Kamis, N.H.H.; Shaleh, S.R.M. Optimization of the Ionic Liquid-Microwave Assisted One-Step Biodiesel Production Process from Wet Microalgal Biomass. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 1397–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yu, X.; Li, H.; Tu, S.-T.; Sebastian, S. Lipids Extraction from Wet Chlorella Pyrenoidosa Sludge Using Recycled [BMIM]Cl. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talhami, M.; Mussa, A.A.; Thaher, M.I.; Das, P.; Abouelela, A.R.; Hawari, A.H. Efficient Extraction of Lipids from Microalgal Biomass for the Production of Biofuels Using Low-Cost Protic Ionic Solvents. Biochem. Eng. J. 2023, 194, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, M.; Chhotaray, P.K.; Gardas, R.L.; Tamilarasan, K.; Rajesh, M. Application of Carboxylate Protic Ionic Liquids in Simultaneous Microalgal Pretreatment and Lipid Recovery from Marine Nannochloropsis sp. and Chlorella sp. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 123, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, R.K.; Fernandez, M.S.; Wijffels, R.H.; Eppink, M.H.M. Mild Fractionation of Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Components From Neochloris Oleoabundans Using Ionic Liquids. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ward, V.; Dennis, D.; Plechkova, N.V.; Armenta, R.; Rehmann, L. Efficient Extraction of a Docosahexaenoic Acid (DHA)-Rich Lipid Fraction from Thraustochytrium sp. Using Ionic Liquids. Materials 2018, 11, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, C.; Mezzetta, A.; Pomelli, C.S.; Iaquaniello, G.; Gentile, A.; Masciocchi, B. Development of Cost-Effective Biodiesel from Microalgae Using Protic Ionic Liquids. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4982–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekghasemi, S.; Kariminia, H.-R.; Plechkova, N.K.; Ward, V.C.A. Direct Transesterification of Wet Microalgae to Biodiesel Using Phosphonium Carboxylate Ionic Liquid Catalysts. Biomass Bioenergy 2021, 150, 106126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olkiewicz, M.; Caporgno, M.P.; Font, J.; Legrand, J.; Lepine, O.; Plechkova, N.V.; Pruvost, J.; Seddon, K.R.; Bengoa, C. A Novel Recovery Process for Lipids from Microalgæ for Biodiesel Production Using a Hydrated Phosphonium Ionic Liquid. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2813–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanudin, N.; Abd Ghani, N.; Ab Rahim, A.H.; Azman, N.S.; Rosdi, N.A.; Masri, A.N. Optimization and Kinetic Studies on Biodiesel Conversion from Chlorella vulgaris Microalgae Using Pyrrolidinium-Based Ionic Liquids as a Catalyst. Catalysts 2022, 12, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, E.T.; Brunner, M.; Atkin, R.; Eltanahy, E.; Thomas-Hall, S.R.; Schenk, P.M. The Ionic Liquid Cholinium Arginate Is an Efficient Solvent for Extracting High-Value Nannochloropsis sp. Lipids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 2538–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez Ruiz, C.A.; Kwaijtaal, J.; Peinado, O.C.; van den Berg, C.; Wijffels, R.H.; Eppink, M.H.M. Multistep Fractionation of Microalgal Biomolecules Using Selective Aqueous Two-Phase Systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, K.S.; Chong, Y.M.; Chang, W.S.; Yap, J.M.; Foo, S.C.; Khoiroh, I.; Lau, P.L.; Chew, K.W.; Ooi, C.W.; Show, P.L. Permeabilization of Chlorella Sorokiniana and Extraction of Lutein by Distillable CO2-Based Alkyl Carbamate Ionic Liquids. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Ho Row, K. Evaluation of CO2-Induced Azole-Based Switchable Ionic Liquid with Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Reversible Transition as Single Solvent System for Coupling Lipid Extraction and Separation from Wet Microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 296, 122309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yin, F.; Liu, C.; Xu, X. Effect of Process Parameters of Microwave Assisted Extraction (MAE) on Polysaccharides Yield from Pumpkin. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. (Engl. Ed.) 2011, 18, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esquivel-Hernández, D.A.; Ibarra-Garza, I.P.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.; Cuéllar-Bermúdez, S.P.; Rostro-Alanis, M.d.J.; Alemán-Nava, G.S.; García-Pérez, J.S.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Green Extraction Technologies for High-Value Metabolites from Algae: A Review. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2017, 11, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.S.; Vian, M.A.; Chemat, F. Solvent-Free Microwave Extraction of Bioactive Compounds Provides a Tool for Green Analytical Chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2013, 47, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva-Echevarría, B.; Goicoechea, E.; Manzanos, M.J.; Guillén, M.D. A Method Based on 1H NMR Spectral Data Useful to Evaluate the Hydrolysis Level in Complex Lipid Mixtures. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, D.; Wells, A.; Hayler, J.; Sneddon, H.; McElroy, C.R.; Abou-Shehada, S.; Dunn, P.J. CHEM21 Selection Guide of Classical- and Less Classical-Solvents. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filoda, P.F.; Fetter, L.F.; Fornasier, F.; Schneider, R.d.C.d.S.; Helfer, G.A.; Tischer, B.; Teichmann, A.; da Costa, A.B. Fast Methodology for Identification of Olive Oil Adulterated with a Mix of Different Vegetable Oils. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, Q.; He, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, H.; He, W. Preparation and Characterization of Ionic Conductive Eutectogels Based on Polyacrylamide Copolymers with Long Hydrophobic Chain. Chinese J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 37, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martínez, M.; Gallardo-Velázquez, T.; Osorio-Revilla, G.; Almaraz-Abarca, N.; Ponce-Mendoza, A.; Vásquez-Murrieta, M.S. Prediction of Total Fat, Fatty Acid Composition and Nutritional Parameters in Fish Fillets Using MID-FTIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matwijczuk, A.; Oniszczuk, T.; Matwijczuk, A.; Chruściel, E.; Kocira, A.; Niemczynowicz, A.; Wójtowicz, A.; Combrzyński, M.; Wiącek, D. Use of FTIR Spectroscopy and Chemometrics with Respect to Storage Conditions of Moldavian Dragonhead Oil. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimon, J.; Salih, N.; Abdullah, B.M. Improvement of Physicochemical Characteristics of Monoepoxide Linoleic Acid Ring Opening for Biolubricant Base Oil. Biomed Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 196565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Xiao, B.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Yang, G. Solvent-Free Synthesis of Phytosterol Linoleic Acid Esters at Low Temperature. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 10738–10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicka, M.; Zieliński, M.; Dudek, M.; Dębowski, M. Effects of Ultrasonic and Microwave Pretreatment on Lipid Extraction of Microalgae and Methane Production from the Residual Extracted Biomass. BioEnergy Res. 2021, 14, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei Motlagh, S.; Harun, R.; Biak, D.R.A.; Hussain, S.A. Microwave Assisted Extraction of Lipid from Nannochloropsis Gaditana Microalgae Using [EMIM]Cl. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 778, 12164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Ascoli, I.; Lees, M.; Meath, J.A.; Lebaron, N. Preparation of Lipide Extracts from Brain Tissue. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 191, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safafar, H.; Ljubic, A.; Møller, P.; Jacobsen, C. Two-Step Direct Transesterification as a Rapid Method for the Analysis of Fatty Acids in Microalgae Biomass. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2019, 121, 1700409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Xiang, L.; Li, X.; Song, Y.; Yang, C.; Ji, F.; Chung, A.C.K.; Li, K.; Lin, Z.; Cai, Z. Derivatization Strategy Combined with Parallel Reaction Monitoring for the Characterization of Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Hydroxylated Derivatives in Mouse. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1100, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.; van Aarssen, B.G.K.; Grice, K. Relative Efficiency of Free Fatty Acid Butyl Esterification Choice of Catalyst and Derivatisation Procedure. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1198–1199, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, S. Derivatization in Gas Chromatography. J. Pharm. Sci. 1976, 65, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, U.; ElShaer, A.; Snyder, L.A.S.; Chaidemenou, A.; Alany, R.G. Fatty Acid Microemulsion for the Treatment of Neonatal Conjunctivitis: Quantification, Characterisation and Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2016, 6, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostermann, A.I.; Müller, M.; Willenberg, I.; Schebb, N.H. Determining the Fatty Acid Composition in Plasma and Tissues as Fatty Acid Methyl Esters Using Gas Chromatography—A Comparison of Different Derivatization and Extraction Procedures. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 2014, 91, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Watkins, B.A. Analysis of Fatty Acids in Food Lipids. In Current Protocols in Food Analytical Chemistry; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2001; pp. D1.2.1–D1.2.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H. Laboratory Manual on Analytical Methods and Procedures for Fish and Fish Products; Marine Fisheries Research Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development: Singapore, 1987; ISBN 9971881586. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS. AOCS Official Method Ce 2-66: Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids. In Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society; American Oil Chemists’ Society: Champaign, IL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Atlaskina, M.E.; Atlaskin, A.A.; Kazarina, O.V.; Petukhov, A.N.; Zarubin, D.M.; Nyuchev, A.V.; Vorotyntsev, A.V.; Vorotyntsev, I.V. Synthesis and Comprehensive Study of Quaternary-Ammonium-Based Sorbents for Natural Gas Sweetening. Environments 2021, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, U.; Bogel-Łukasik, R. Physicochemical Properties and Solubility of Alkyl-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-Dimethylammonium Bromide. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 12124–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FAMEs | Soxhlet CHCl3:MeOH (2:1) | Bligh & Dyer | Soxhlet n-Hexane | Folch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4:0 | 0.04 * (0.09%) | 0.03 * (0.17%) | 0.01 * (0.11%) | 0.01 * (0.17%) |

| C6:0 | 0.03 * (0.07%) | 0.01 * (0.06%) | 0.01 * (0.22%) | n.d. |

| C10:0 | 0.12 * (0.29%) | 0.04 * (0.23%) | 0.01 * (0.18%) | 0.02 * (0.32%) |

| C12:0 | 0.06 * (0.14%) | 0.01 * (0.05%) | 0.01 * (0.20%) | n.d. |

| C14:0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 (0.58%) | 0.07 ± 0.01 (0.39%) | 0.05 * (0.94%) | 0.02 * (0.35%) |

| C15:0 | 0.17 ± 0.01 (0.39%) | 0.06 * (0.33%) | 0.03 * (0.48%) | 0.01 * (0.27%) |

| C16:2 trans | 2.76 ± 0.12 (6.41%) | 1.06 ± 0.01 (6.08%) | 0.10 * (1.71%) | 0.34 ± 0.03 (6.18%) |

| C16:3 trans | 6.35 ± 0.08 (14.74%) | 2.60 ± 0.10 (14.94%) | 0.25 ± 0.01 (4.49%) | 0.85 ± 0.04 (15.42%) |

| C16:1 cis | 0.91 ± 0.03 (2.10%) | 0.38 ± 0.03 (2.19%) | 0.07 * (1.18%) | 0.13 * (2.37%) |

| C16:1 trans | 0.34 ± 0.02 (0.79%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.75%) | 0.02 * (0.42%) | 0.04 * (0.78%) |

| C16:0 | 7.90 ± 0.07 (18.33%) | 2.97 ± 0.15 (17.05%) | 1.34 ± 0.07 (23.82%) | 0.91 ± 0.02 (16.63%) |

| 15-Methylpalmitic acid | 1.11 ± 0.05 (2.57%) | 0.41 ± 0.01 (2.35%) | 0.04 * (0.77%) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (2.22%) |

| Mix of compounds to C17 derived FAMEs | 2.81 ± 0.15 (6.51%) | 1.27 ± 0.08 (7.30%) | 0.98 ± 0.08 (17.43%) | 0.37 ± 0.02 (6.65%) |

| Cascarillic acid | 0.16 ± 0.01 (0.38%) | 0.06 * (0.34%) | 0.01 * (0.18%) | 0.02 * (0.38%) |

| C17:3 cis | 0.31 ± 0.01 (0.72%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (0.61%) | 0.01 * (0.09%) | 0.03 * (0.57%) |

| C17:0 | 0.46 ± 0.04 (1.06%) | 0.18 ± 0.02 (1.06%) | 0.03 * (0.46%) | 0.05 * (0.93%) |

| C18:2 cis | 5.95 ± 0.14 (13.81%) | 2.55 ± 0.17 (14.64%) | 0.23 * (4.15%) | 0.75 ± 0.06 (13.67%) |

| C18:3 trans + C18:1 cis + C18:2 trans | 10.99 ± 0.35 (25.49%) | 4.59 ± 0.09 (26.36%) | 1.74 ± 0.02 (30.86%) | 1.51 ± 0.07 (27.49%) |

| C18:1 trans | 0.85 ± 0.04 (1.96%) | 0.34 ± 0.03 (1.95%) | 0.05 * (0.82%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (2.09%) |

| C18:0 | 1.00 ± 0.08 (2.33%) | 0.42 ± 0.03 (2.40%) | 0.52 ± 0.02 (9.26%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (2.47%) |

| C20:4 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.29%) | 0.03 * (0.19%) | 0.02 * (0.34%) | 0.02 * (0.31%) |

| C20:5 | 0.07 * (0.15%) | 0.02 * (0.11%) | 0.01 * (0.15%) | 0.01 * (0.20%) |

| C20:0 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.31%) | 0.03 * (0.17%) | 0.03 * (0.59%) | 0.01 * (0.24%) |

| C24:0 | 0.21 ± 0.02 (0.49%) | 0.05 * (0.28%) | 0.07 * (1.15%) | 0.02 * (0.30%) |

| Total | 43.10 ± 0.21 (100%) | 17.41 ± 0.54 (100%) | 5.64 ± 0.19 (100%) | 5.49 ± 0.29 (100%) |

| FAMEs | w/o IL and w/o MW | w/o IL and w/MW | 1:4 (algae/IL) | 1:8 (algae/IL) | 1:8 (algae/IL) Recycled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4:0 | n.d. | 0.01 * (0.13%) | 0.02 * (0.24%) | 0.04 * (0.15%) | 0.03 * (0.13%) |

| C6:0 | 0.01 * (0.29%) | 0.02 * (0.34%) | 0.06 ± 0.01 (0.84%) | 0.12 * (0.48%) | 0.11 * (0.44%) |

| C10:0 | 0.01 * (0.19%) | 0.01 * (0.14%) | 0.02 * (0.28%) | 0.03 * (0.12%) | 0.04 * (0.15%) |

| C12:0 | 0.01 * (0.11%) | 0.01 * (0.11%) | 0.02 * (0.22%) | 0.02 * (0.10%) | 0.04 * (0.16%) |

| C14:0 | 0.04 * (0.79%) | 0.03 * (0.55%) | 0.06 * (0.85%) | 0.14 * (0.56%) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (0.61%) |

| C15:0 | 0.02 * (0.34%) | 0.01 * (0.24%) | 0.02 * (0.29%) | 0.07 * (0.28%) | 0.07 * (0.26%) |

| C16:2 trans | 0.06 * (1.24%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (2.76%) | 0.37 ± 0.03 (4.81%) | 1.41 ± 0.03 (5.76%) | 1.07 ± 0.03 (4.28%) |

| C16:3 trans | 0.18 ± 0.01 (3.71%) | 0.19 ± 0.01 (3.78%) | 1.02 ± 0.05 (13.40%) | 3.31 ± 0.04 (13.51%) | 2.89 ± 0.07 (11.52%) |

| C16:1 cis | 0.03 * (0.64%) | 0.06 ± 0.01 (1.25%) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (1.18%) | 0.43 ± 0.01 (1.74%) | 0.32 ± 0.02 (1.27%) |

| C16:1 trans | 0.04 * (0.80%) | 0.04 * (0.74%) | 0.15 * (1.93%) | 0.17 * (0.71%) | 0.25 ± 0.01 (0.99%) |

| C16:0 | 0.92 ± 0.06 (19.14%) | 0.88 ± 0.02 (17.44%) | 1.39 ± 0.08 (18.31%) | 4.24 ± 0.09 (17.34%) | 4.48 ± 0.15 (17.84%) |

| 15-Methylpalmitic acid | 0.04 * (0.84%) | 0.04 * (0.73%) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (2.01%) | 0.53 ± 0.02 (2.17%) | 0.45 ± 0.02 (1.78%) |

| Mix of compounds to C17 derived FAMEs | 2.44 ± 0.16 (50.62%) | 2.52 ± 0.09 (50.12%) | 1.02 ± 0.06 (13.43%) | 1.84 ± 0.10 (7.51%) | 3.41 ± 0.04 (13.58%) |

| Cascarillic acid | 0.01 * (0.22%) | 0.01 * (0.16%) | 0.02 * (0.20%) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.34%) | 0.07 * (0.30%) |

| C17:3 cis | n.d. | 0.03 * (0.66%) | 0.03 * (0.36%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.51%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (0.44%) |

| C17:0 | 0.02 * (0.38%) | 0.02 * (0.42%) | 0.05 * (0.65%) | 0.20 * (0.83%) | 0.17 ± 0.01 (0.66%) |

| C18:2 cis | 0.15 ± 0.01 (3.01%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (2.71%) | 0.83 ± 0.07 (10.87%) | 3.47 ± 0.20 (14.20%) | 3.01 ± 0.03 (12.01%) |

| C18:3 trans + C18:1 cis + C18:2 trans | 0.24 ± 0.01 (5.07%) | 0.24 ± 0.01 (4.79%) | 1.64 ± 0.10 (21.61%) | 6.73 ± 0.19 (27.50%) | 6.19 ± 0.12 (24.68%) |

| C18:1 trans | 0.05 * (1.01%) | 0.02 * (0.46%) | 0.07 * (0.86%) | 0.32 * (1.32%) | 0.37 ± 0.02 (1.47%) |

| C18:0 | 0.52 ± 0.03 (10.79%) | 0.49 ± 0.02 (9.75%) | 0.43 ± 0.01 (5.71%) | 0.90 ± 0.01 (3.69%) | 1.50 ± 0.07 (6.00%) |

| C20:4 | n.d. | 0.02 * (0.42%) | 0.02 * (0.29%) | 0.06 * (0.25%) | 0.03 * (0.12%) |

| C20:5 | n.d. | 0.01 * (0.15%) | 0.01 * (0.15%) | 0.03 * (0.14%) | 0.02 * (0.08%) |

| C20:0 | 0.01 * (0.11%) | 0.06 * (1.25%) | 0.05 * (0.62%) | 0.04 * (0.16%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (0.57%) |

| C24:0 | 0.03 * (0.71%) | 0.04 * (0.89%) | 0.07 * (0.87%) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (0.62%) | 0.16 ± 0.01 (0.63%) |

| Total | 4.82 ± 0.26 (100%) | 5.02 ± 0.18 (100%) | 7.61 ± 0.30 (100%) | 24.46 ± 0.48 (100%) | 25.08 ± 0.23 (100%) |

| FAMEs | Soxhlet CHCl3:MeOH (2:1) | Bligh & Dyer | AcEt/EtOH (1:1) | Supernatant w/o IL and w/MW | Biomass Sediment w/o IL and w/MW | Extraction Total w/o IL and w/MW | Supernatant 1:8 (algae/IL) | Biomass Sediment 1:8 (algae/IL) | Extraction Total 1:8 (algae/IL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C4:0 | 0.04 * (0.09%) | 0.03 * (0.17%) | 0.01 * (0.08%) | 0.01 * (0.13%) | 0.01 * (0.07%) | 0.02 * (0.09%) | 0.04 * (0.15%) | 0.02 * (0.09%) | 0.05 * (0.12%) |

| C6:0 | 0.03 * (0.07%) | 0.01 * (0.06%) | 0.01 * (0.06%) | 0.02 * (0.34%) | 0.01 * (0.08%) | 0.03 * (0.14%) | 0.12 * (0.48%) | 0.02 * (0.08%) | 0.13 * (0.31%) |

| C10:0 | 0.12 * (0.29%) | 0.04 * (0.23%) | 0.03 * (0.16%) | 0.01 * (0.14%) | 0.02 * (0.11%) | 0.03 * (0.12%) | 0.03 * (0.12%) | 0.02 * (0.13%) | 0.05 * (0.12%) |

| C12:0 | 0.06 * (0.14%) | 0.01 * (0.05%) | 0.01 * (0.07%) | 0.01 * (0.11%) | 0.01 * (0.06%) | 0.02 * (0.07%) | 0.02 * (0.10%) | 0.01 * (0.07%) | 0.04 * (0.09%) |

| C14:0 | 0.25 ± 0.02 (0.58%) | 0.07 ± 0.01 (0.39%) | 0.07 * (0.46%) | 0.03 * (0.55%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (0.64%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.62%) | 0.14 * (0.56%) | 0.09 *(0.49%) | 0.23 (0.53%) |

| C15:0 | 0.17 ± 0.01 (0.39%) | 0.06 * (0.33%) | 0.06 * (0.36%) | 0.01 * (0.24%) | 0.07 ± 0.01 (0.44%) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.39%) | 0.07 * (0.28%) | 0.06 * (0.32%) | 0.13 (0.30%) |

| C16:2 trans | 2.76 ± 0.12 (6.41%) | 1.06 ± 0.01 (6.08%) | 0.90 ± 0.07 (5.76%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (2.76%) | 0.77 ± 0.05 (4.69%) | 0.90 ± 0.04 (4.23%) | 1.41 ± 0.03 (5.76%) | 1.16 ± 0.07 (6.43%) | 2.57 ± 0.06 (6.05%) |

| C16:3 trans | 6.35 ± 0.08 (14.74%) | 2.60 ± 0.10 (14.94%) | 2.00 ± 0.14 (12.74%) | 0.19 ± 0.01 (3.78%) | 1.99 ± 0.14 (12.19%) | 2.02 ± 0.14 (9.45%) | 3.31 ± 0.04 (13.51%) | 2.65 ± 0.08 (14.63%) | 5.95 ± 0.11 (13.99%) |

| C16:1 cis | 0.91 ± 0.03 (2.10%) | 0.38 ± 0.03 (2.19%) | 0.31 ± 0.02 (1.98%) | 0.06 ± 0.01 (1.25%) | 0.28 * (1.70%) | 0.34 * (1.59%) | 0.43 ± 0.01 (1.74%) | 0.36 ± 0.01 (1.99%) | 0.79 ± 0.02 (1.85%) |

| C16:1 trans | 0.34 ± 0.02 (0.79%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.75%) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (0.76%) | 0.04 * (0.74%) | 0.02 * (0.10%) | 0.05 * (0.25%) | 0.17 * (0.71%) | 0.17 ± 0.01 (0.95%) | 0.35 ± 0.01 (0.82%) |

| C16:0 | 7.90 ± 0.07 (18.33%) | 2.97 ± 0.15 (17.05%) | 2.92 ± 0.21 (18.56%) | 0.88 ± 0.02 (17.44%) | 4.19 ± 0.37 (25.64%) | 5.06 ± 0.40 (23.67%) | 4.24 ± 0.09 (17.34%) | 2.87 ± 0.12 (15.89%) | 7.12 ± 0.19 (16.72%) |

| 15-Methylpalmitic acid | 1.11 ± 0.05 (2.57%) | 0.41 ± 0.01 (2.35%) | 0.39 ± 0.02 (2.51%) | 0.04 * (0.73%) | 0.51 ± 0.05 (3.14%) | 0.55 ± 0.05 (2.57%) | 0.53 ± 0.02 (2.17%) | 0.38 ± 0.03 (2.12%) | 0.91 ± 0.04 (2.15%) |

| Mix of compounds to C17 derived FAMEs | 2.81 ± 0.15 (6.51%) | 1.27 ± 0.08 (7.30%) | 1.50 ± 0.13 (9.53%) | 2.52 ± 0.09 (50.12%) | 1.37 ± 0.11 (8.40%) | 4.09 ± 0.22 (19.11%) | 1.84 ± 0.10 (7.51%) | 1.71 ± 0.04 (9.47%) | 3.55 ± 0.14 (8.35%) |

| Cascarillic acid | 0.16 ± 0.01 (0.38%) | 0.06 * (0.34%) | 0.03 * (0.18%) | 0.01 * (0.16%) | 0.02 * (0.12%) | 0.03 * (0.13%) | 0.08 ± 0.01 (0.34%) | 0.07 * (0.37%) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (0.35%) |

| C17:3 cis | 0.31 ± 0.01 (0.72%) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (0.61%) | 0.01 * (0.08%) | 0.03 * (0.66%) | 0.06 * (0.39%) | 0.10 * (0.45%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.51%) | 0.01 * (0.07%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (0.32%) |

| C17:0 | 0.46 ± 0.04 (1.06%) | 0.18 ± 0.02 (1.06%) | 0.17 ± 0.01 (1.07%) | 0.02 * (0.42%) | 0.22 ± 0.02 (1.33%) | 0.24 ± 0.02 (1.11%) | 0.20 * (0.83%) | 0.17 * (0.91%) | 0.37 * (0.87%) |

| C18:2 cis | 5.95 ± 0.14 (13.81%) | 2.55 ± 0.17 (14.64%) | 2.22 ± 0.07 (14.14%) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (2.71%) | 1.93 ± 0.13 (11.80%) | 2.06 ± 0.13 (9.64%) | 3.47 ± 0.20 (14.20%) | 2.37 ± 0.07 (13.12%) | 5.85 ± 0.23 (13.74%) |

| C18:3 trans + C18:1 cis + C18:2 trans | 10.99 ± 0.35 (25.49%) | 4.59 ± 0.09 (26.36%) | 3.91 ± 0.14 (24.87%) | 0.24 ± 0.01 (4.79%) | 3.53 ± 0.25 (21.61%) | 3.77 ± 0.26 (17.62%) | 6.73 ± 0.19 (27.50%) | 4.72 ± 0.16 (26.11%) | 11.45 ± 0.34 (26.91%) |

| C18:1 trans | 0.85 ± 0.04 (1.96%) | 0.34 ± 0.03 (1.95%) | 0.34 ± 0.02 (2.14%) | 0.02 * (0.46%) | 0.28 ± 0.01 (1.74%) | 0.31 ± 0.01 (1.44%) | 0.32 * (1.32%) | 0.39 ± 0.02 (2.15%) | 0.71 ± 0.02 (1.67%) |

| C18:0 | 1.00 ± 0.08 (2.33%) | 0.42 ± 0.03 (2.40%) | 0.52 ± 0.03 (3.31%) | 0.49 ± 0.02 (9.75%) | 0.71 ± 0.03 (4.32%) | 1.20 ± 0.05 (5.59%) | 0.90 ± 0.01 (3.69%) | 0.63 ± 0.05 (3.51%) | 1.54 ± 0.04 (3.61%) |

| C20:4 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.29%) | 0.03 * (0.19%) | 0.08 * (0.52%) | 0.02 * (0.42%) | 0.10 ± 0.01 (0.60%) | 0.12 ± 0.01 (0.56%) | 0.06 * (0.25%) | 0.07 * (0.37%) | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.30%) |

| C20:5 | 0.07 * (0.15%) | 0.02 * (0.11%) | 0.02 * (0.12%) | 0.01 * (0.15%) | 0.04 * (0.22%) | 0.04 * (0.21%) | 0.03 * (0.14%) | 0.02 * (0.10%) | 0.05 * (0.12%) |

| C20:0 | 0.13 ± 0.01 (0.31%) | 0.03 * (0.17%) | 0.04 * (0.27%) | 0.06 * (1.25%) | 0.05 * (0.29%) | 0.11 * (0.52%) | 0.04 * (0.16%) | 0.06 * (0.32%) | 0.10 ± 0.01 (0.23%) |

| C24:0 | 0.21 ± 0.02 (0.49%) | 0.05 * (0.28%) | 0.04 * (0.27%) | 0.04 * (0.89%) | 0.05 * (0.30%) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (0.44%) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (0.62%) | 0.06 * (0.30%) | 0.21 ± 0.01 (0.48%) |

| Total | 43.10 ± 0.21 (100%) | 17.41 ± 0.54 (100%) | 15.71 ± 0.61 (100%) | 5.02 ± 0.18 (100%) | 16.32 ± 0.45 (100%) | 21.39 ± 0.58 (100%) | 24.46 ± 0.48 (100%) | 18.09 ± 0.35 (100%) | 42.56 ± 0.64 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agostinho, D.A.S.; Santos, A.F.M.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Reis, P.M.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Ventura, M.G. From Biomass to Efficient Lipid Recovery: Choline-Based Ionic Liquids and Microwave Extraction of Chlorella vulgaris. Molecules 2025, 30, 4611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234611

Agostinho DAS, Santos AFM, Esperança JMSS, Reis PM, Duarte ARC, Ventura MG. From Biomass to Efficient Lipid Recovery: Choline-Based Ionic Liquids and Microwave Extraction of Chlorella vulgaris. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234611

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgostinho, Daniela A. S., Andreia F. M. Santos, José M. S. S. Esperança, Patrícia M. Reis, Ana Rita C. Duarte, and Márcia G. Ventura. 2025. "From Biomass to Efficient Lipid Recovery: Choline-Based Ionic Liquids and Microwave Extraction of Chlorella vulgaris" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234611

APA StyleAgostinho, D. A. S., Santos, A. F. M., Esperança, J. M. S. S., Reis, P. M., Duarte, A. R. C., & Ventura, M. G. (2025). From Biomass to Efficient Lipid Recovery: Choline-Based Ionic Liquids and Microwave Extraction of Chlorella vulgaris. Molecules, 30(23), 4611. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234611