Ocular Toxicity and Mechanistic Investigation for Berberine and Its Metabolite Berberrubine on Zebrafish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Cytotoxicity of BBR and Its Analogs on HCE-T Cell Line

2.2. Ocular Toxicity Evaluations of BBR and M1 in Zebrafish

2.2.1. General Toxicity of BBR and M1 in Zebrafish

2.2.2. Ocular Toxicity of BBR and M1 in Zebrafish

2.2.3. Effects of BBR and M1 on the Locomotor Behavior of Zebrafish Larvae

2.3. BBR and M1 Induce Apoptosis in Ocular Cells

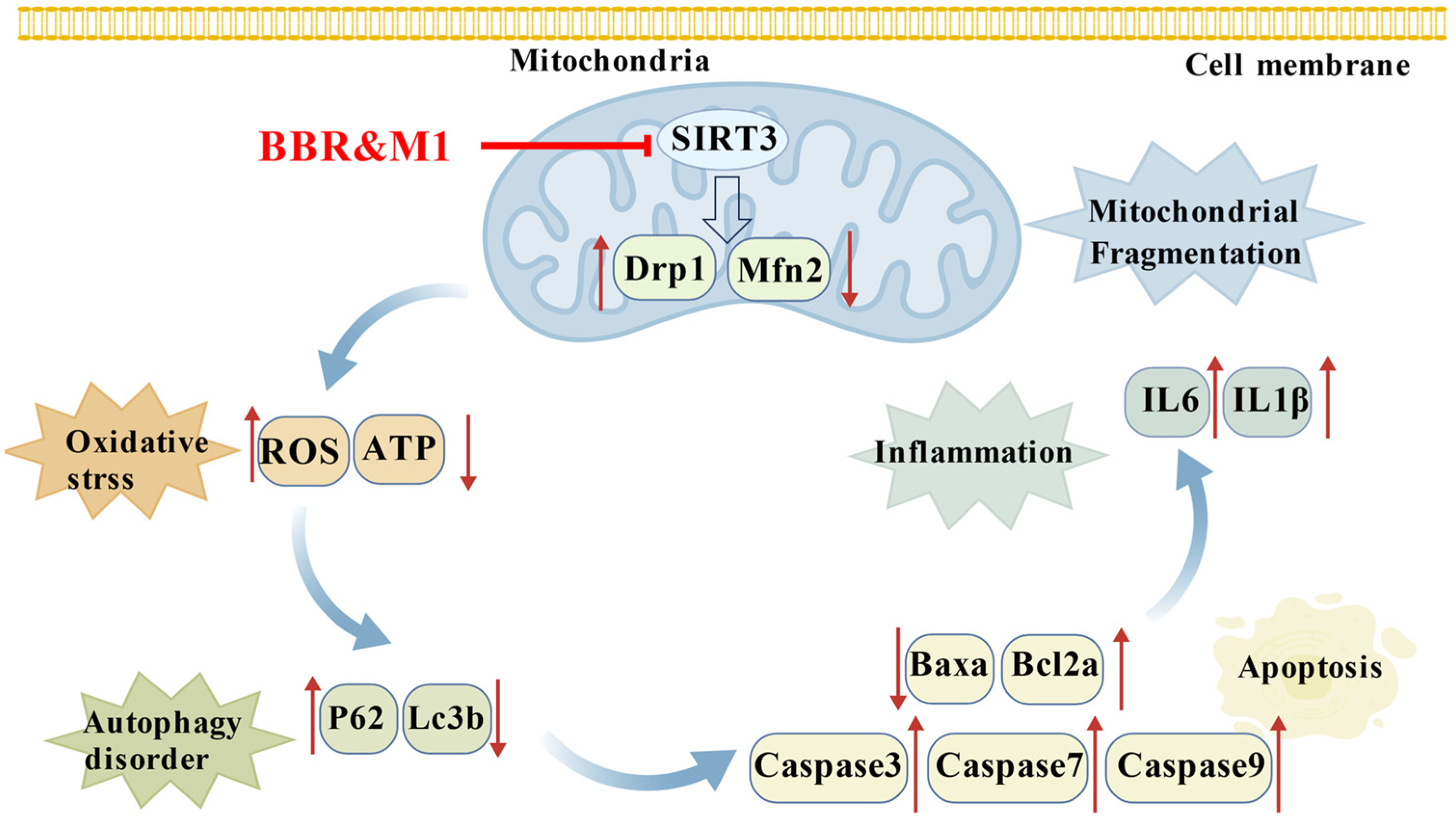

2.4. BBR and M1 Inhibit the Activity of Mitochondrial Complex I

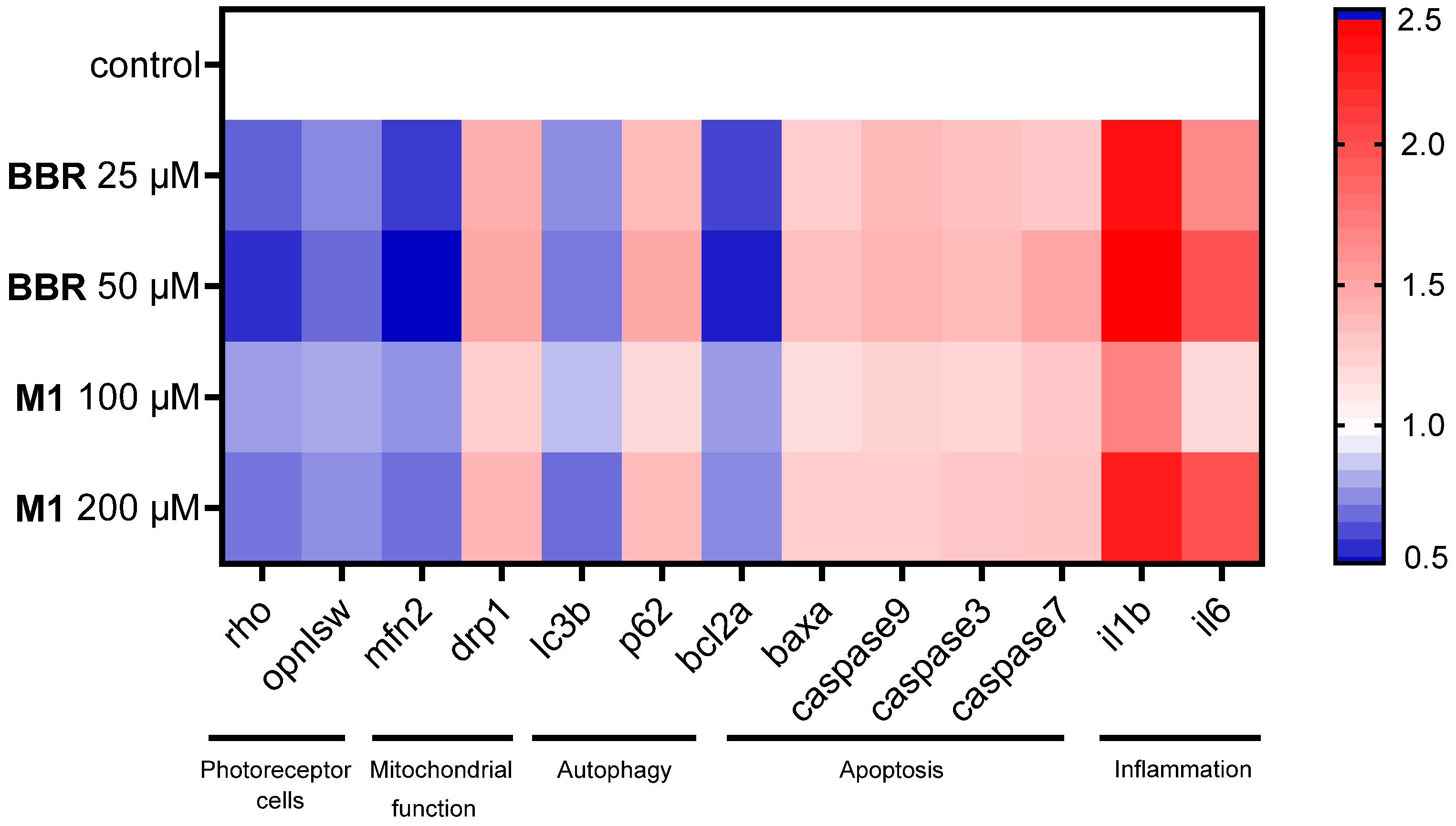

2.5. BBR and M1 Disrupt Zebrafish Genome Maintenance and Functions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

4.2. Cell and Cell Culture

4.3. MTT Assay

4.4. Zebrafish Models

4.5. Zebrafish Embryonic Developmental Toxicity

4.6. Zebrafish Eye Length and Area Experiment

4.7. Zebrafish Visual Motor Response Experiment

4.8. Fluorescence Microscopy for Ocular Cell Apoptosis

4.9. Fluorescence Microscopy for Mitochondrial Function

4.10. Determination of Cellular ATP and ROS Levels

4.11. Mitochondrial Complex I Activity Assay

4.12. RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

4.13. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

4.14. Molecular Docking

4.15. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BBR | berberine |

| SIRT3 | Sirtuin 3 |

| DR | diabetic retinopathy |

| RGCs | retinal ganglion cells |

| TAO | thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy |

| OFs | orbital fibroblasts |

| M1 | berberrubine |

| M3 | demethyleneberberine |

| M4 | jatrorrhizine |

| PAL | palmatine |

| DPAL | dehydroxypalmatine |

| CBBR | cycloberberine |

| STE | short-term exposure |

| LC50 | half-lethal concentration |

| ETC | electron transport chain |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| qPCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| OCTs | organic cation transporters |

References

- Wang, L.H.; Huang, C.H.; Lin, I.C. Advances in neuroprotection in glaucoma: Pharmacological strategies and emerging technologies. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, T.; Nejima, R.; Miyata, K. Ocular surface flora and prophylactic antibiotics for cataract surgery in the age of antimicrobial resistance. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, C. New Anti-VEGF Drugs in Ophthalmology. Curr. Drug Targets 2020, 21, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbabi, A.; Bao, X.; Shalaby, W.S.; Razeghinejad, R. Systemic side effects of glaucoma medications. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2022, 105, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippelli, M.; dell’Omo, R.; Gelso, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Bartollino, S.; Napolitano, P.; Russo, A.; Campagna, G.; Costagliola, C. Effects of topical low-dose preservative-free hydrocortisone on intraocular pressure in patients affected by ocular surface disease with and without glaucoma. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, J. Berberine protects against dysentery by targeting both Shigella filamentous temperature sensitive protein Z and host pyroptosis: Resolving in vitro-vivo effect discrepancy. Phytomedicine 2025, 139, 156517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Asghar, F.; Zafar, S.; Oliinyk, P.; Khavrona, O.; Lysiuk, R.; Peana, M.; Piscopo, S.; Antonyak, H.; Pen, J.J.; et al. Berberine: Pharmacological features in health, disease and aging. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 1214–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Li, K.; Peng, X.X.; Yao, T.J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Hu, P.; Cai, D.; Liu, H.Y. Berberine a traditional Chinese drug repurposing: Its actions in inflammation-associated ulcerative colitis and cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1083788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Yin, J.; Chen, J.; Ma, J.; Si, H.; Xia, D. Inhibition of inflammation by berberine: Molecular mechanism and network pharmacology analysis. Phytomedicine 2024, 128, 155258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Ji, Y.; Yan, X.; Su, G.; Chen, L.; Xiao, J. Berberine attenuates apoptosis in rat retinal Müller cells stimulated with high glucose via enhancing autophagy and the AMPK/mTOR signaling. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 108, 1201–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, J.; Li, M.; Ma, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Berberine protects against diabetic retinopathy by inhibiting cell apoptosis via deactivation of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 4227–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayasaka, S.; Kodama, T.; Ohira, A. Traditional Japanese herbal (kampo) medicines and treatment of ocular diseases: A review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2012, 40, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Huang, X.; Wu, K.; Zong, Y.; Yu, J.; Xu, H.; Shi, J.; Wei, J.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, C. Activation of the GABA-alpha receptor by berberine rescues retinal ganglion cells to attenuate experimental diabetic retinopathy. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 930599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, J.; Chen, X.; Mou, P.; Ma, X.; Wei, R. Potential therapeutic activity of berberine in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: Inhibitory effects on tissue remodeling in orbital fibroblasts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Y.; Tan, H.Y.; Chen, H.; Feng, Y. Berberine improves insulin-induced diabetic retinopathy through exclusively suppressing Akt/mTOR-mediated HIF-1α/VEGF activation in retina endothelial cells. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 4316–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, D.; Feng, P.F.; Sun, J.L.; Guo, F.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, B.X. The enhancement of cardiac toxicity by concomitant administration of Berberine and macrolides. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 76, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kysenius, K.; Brunello, C.A.; Huttunen, H.J. Mitochondria and NMDA receptor-dependent toxicity of berberine sensitizes neurons to glutamate and rotenone injury. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Feng, X.; Chai, L.; Cao, S.; Qiu, F. The metabolism of berberine and its contribution to the pharmacological effects. Drug Metab. Rev. 2017, 49, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzi, S.; Malekahmadi, M.; Ghayour-Mobarhan, M.; Ferns, G.; Rahimi, H.R. Barberry in the treatment of obesity and metabolic syndrome: Possible mechanisms of action. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2018, 11, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saklani, P.; Khan, H.; Singh, T.G.; Gupta, S.; Grewal, A.K. Demethyleneberberine, a potential therapeutic agent in neurodegenerative disorders: A proposed mechanistic insight. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 10101–10113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Wang, K.; Cao, S.; Ding, L.; Qiu, F. Pharmacokinetics and excretion of berberine and its nine metabolites in rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 594852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.S.; Hayasaka, S.; Zheng, L.S.; Hayasaka, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chi, Z.L. Effect of berberine on monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant-1 expression in rat lipopolysaccharide-induced uveitis. Ophthalmic Res. 2007, 39, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, H.; Seykora, J.T.; Lee, V. Invisible shield: Review of the corneal epithelium as a barrier to UV radiation, pathogens, and other environmental stimuli. J. Ophthalmic Vis. Res. 2017, 12, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassar, S.; Dunn, C.; Ramos, M.F. Zebrafish as an animal model for ocular toxicity testing: A review of ocular anatomy and functional assays. Toxicol. Pathol. 2021, 49, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, Z.; Lin, C.; Hu, H.; Du, J.; Huang, S.; Huang, S.; Gao, J.; Guo, X. Human milk-derived 5′-UMP promotes thermogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis to ameliorate obesity. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1661778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.Z.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.B. Mitochondrial electron transport chain, ROS generation and uncoupling (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijter, N.; van der Zee, M.; Katsumiti, A.; Boyles, M.; Cassee, F.R.; Braakhuis, H. Improving the dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein (DCFH) assay for the assessment of intracellular reactive oxygen species formation by nanomaterials. NanoImpact 2024, 35, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrosimov, R.; Baeken, M.W.; Hauf, S.; Wittig, I.; Hajieva, P.; Perrone, C.E.; Moosmann, B. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition triggers NAD+-independent glucose oxidation via successive NADPH formation, “futile” fatty acid cycling, and FADH2 oxidation. Geroscience 2024, 46, 3635–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Li, J.; Lei, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Jiang, J.; Li, H.; Tang, M.; et al. Berberine dissociates mitochondrial complex I by SIRT3-dependent deacetylation of NDUFS1 to improve hepatocellular glucose and lipid metabolism. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 2676–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zeeshan, M.; Dang, Y.; Liang, L.Y.; Gong, Y.C.; Li, Q.Q.; Tan, Y.W.; Fan, Y.Y.; Lin, L.Z.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Environmentally relevant concentrations of F-53B induce eye development disorders-mediated locomotor behavior in zebrafish larvae. Chemosphere 2022, 30, 136130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, H.; Cong, L.; Xu, J.; Shen, Z.; Chen, W.; et al. Sirt3 deficiency accelerates ovarian senescence without affecting spermatogenesis in aging mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, F.; Tao, H. A preliminary study on the safety of berberine solution in rabbit eyes with topical application. Zhonghua Yan Ke Za Zhi 2020, 56, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Chignell, C.F.; Sik, R.H.; Watson, M.A.; Wielgus, A.R. Photochemistry and photocytotoxicity of alkaloids from Goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis L.) 3: Effect on human lens and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007, 83, 938–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Medical Products Administration (NMPA). National Drug Standard WS-10001-(HD-0492)-2002: Berberine Hydrochloride Eye Drops; China Medical Science Press: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, J.; Lü, F.; Zhou, X.; Mao, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, S. A Pharmaceutical Composition for Preventing, Alleviating or Treating Ocular Diseases, Its Preparation Method and Application: China. CN116474105A, 28 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, B.H.; Kim, H.S.; Song, S.; Lee, I.H.; Liu, J.; Vassilopoulos, A.; Deng, C.X.; Finkel, T. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14447–14452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Liu, C.X.; Xu, W.; Huang, L.; Zhao, J.Y.; Zhao, S.M. Butyrate induces apoptosis by activating PDC and inhibiting complex I through SIRT3 inactivation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 16035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Park, S.H.; Liu, G.; O’Brien, J.; Jiang, H.; Gius, D. SIRT3-mediated dimerization of IDH2 Directs cancer cell metabolism and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 3990–3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Sui, M.; Chen, R.; Lu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, L. SIRT3 protects kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion injury by modulating the DRP1 pathway to induce mitochondrial autophagy. Life Sci. 2021, 286, 120005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morigi, M.; Perico, L.; Rota, C.; Longaretti, L.; Conti, S.; Rottoli, D.; Novelli, R.; Remuzzi, G.; Enigni, A. Sirtuin 3-dependent mitochondrial dynamic improvements protect against acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Tang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; Luo, Y. CXCR7 promotes melanoma tumorigenesis via Src kinase signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, Y.; Tao, K.; Wen, X.; Feng, D.; Mai, Z.; Ding, H.; Mao, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, Q.; Xiang, J.; et al. SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of DRP1K711 prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2411235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, W.; Guo, T.; Yuan, J.; Wu, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Q.; Liu, N.; et al. SIRT1 restores mitochondrial structure and function in rats by activating SIRT3 after cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2024, 40, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Mu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Wu, J.; Tang, H.; Zheng, S.; Liu, Y.; et al. Generic Diagramming Platform (GDP): A comprehensive database of high-quality biomedical graphics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1670–D1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Carmer, R.; Zhang, G.; Venkatraman, P.; Brown, S.A.; Pang, C.P.; Zhang, M.; Ma, P.; Leung, Y.F. Statistical analysis of zebrafish locomotor response. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, T.; Tang, J.; Lu, X.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J.; Song, D.; Zhang, D.; Xu, M. Ocular Toxicity and Mechanistic Investigation for Berberine and Its Metabolite Berberrubine on Zebrafish. Molecules 2025, 30, 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234602

Liu T, Tang J, Lu X, Jiang L, Zhang R, Zhang M, Zhang J, Song D, Zhang D, Xu M. Ocular Toxicity and Mechanistic Investigation for Berberine and Its Metabolite Berberrubine on Zebrafish. Molecules. 2025; 30(23):4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234602

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ting, Jia Tang, Xinyi Lu, Lu Jiang, Rui Zhang, Miaoqing Zhang, Jingpu Zhang, Danqing Song, Dousheng Zhang, and Mingzhe Xu. 2025. "Ocular Toxicity and Mechanistic Investigation for Berberine and Its Metabolite Berberrubine on Zebrafish" Molecules 30, no. 23: 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234602

APA StyleLiu, T., Tang, J., Lu, X., Jiang, L., Zhang, R., Zhang, M., Zhang, J., Song, D., Zhang, D., & Xu, M. (2025). Ocular Toxicity and Mechanistic Investigation for Berberine and Its Metabolite Berberrubine on Zebrafish. Molecules, 30(23), 4602. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules30234602